Development and Application of a Sustainability Indicator (WPSI) for Wood Preservative Treatments in Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Developing a Wood Protection Sustainability Index (WPSI)

2.2. Assessment of Economic Viability, Industry Challenges, and ESG Criteria

3. Results and Discussion

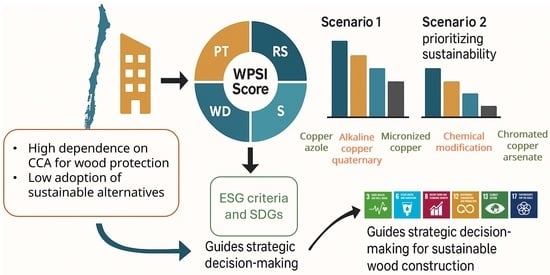

3.1. Classification of Protection Mechanisms Using a Wood Protection Sustainability Index (WPSI)

3.1.1. Scenario 1

3.1.2. Scenario 2

3.2. Assessing the Market Viability of Alternatives to CCA in Chile

3.3. Alignment of Advanced Wood Preservatives with ESG Criteria and SDG Targets

3.4. Strategic SWOT Analysis of Chile’s Wood Preservative Sector Considering ESG Criteria

3.4.1. Strengths

3.4.2. Weaknesses

3.4.3. Opportunities

3.4.4. Threats

3.5. Limitations and Transferability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for Prioritizing Decision Criteria

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Definition of Goal and Criteria | The main objective was defined, and four evaluation criteria were established: PT, WD, RS (as per NCh819:2019), and S. |

| 2. Pairwise Comparison Matrix Construction | Experts performed pairwise comparisons using Saaty’s fundamental scale (1–9) to express the relative importance of each factor. Expert judgment prioritized PT as the most important, followed by S, with WD and RS considered equally important. |

| 3. Matrix Normalization | Each matrix column was normalized by dividing individual values by the column sum. Then, the average of each row yielded the relative weight of each factor. |

| 4. Consistency Check | The consistency of expert judgments was assessed using the Consistency Ratio (CR). We calculated the maximum average value (λmax), Consistency Index (CI), and Random Index (RI), confirming that the condition CR < 0.1 was satisfied, indicating acceptable consistency. |

| 5. Application of Weights | The finalized weights were used to prioritize the decision criteria in further analysis or decision-making models. |

- Preservative Treatments (PT) were deemed the most critical, with significantly higher importance than the other criteria.

- Sustainability (S) was considered the second most important, due to increasing regulatory and environmental concerns.

- Wood Durability (WD) and In-Service Risk Classes (RS) were viewed as equally important and less influential than PT and S.

- PT was assessed as 4 times more important than WD and RS

- PT was 3 times more important than S

- S was 1.5 times more important than WD and RS

- WD and RS were equally important

Appendix A.1.1. Pairwise Comparison Matrix (A)—Scenario 1

| Attribute | Final Weight | Expert Expected Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Preservative Treatments (PT) | 0.543 | 0.50 |

| Wood Durability (WD) | 0.132 | 0.15 |

| Service Risk Classes (RS) | 0.132 | 0.15 |

| Sustainability (S) | 0.192 | 0.20 |

| Attribute | A wi | wi | λi = (A·wi)/wi |

|---|---|---|---|

| PT | 2.175 | 0.543 | 4.004 |

| WD | 0.529 | 0.132 | 4.008 |

| RS | 0.529 | 0.132 | 4.008 |

| S | 0.769 | 0.192 | 4.005 |

Appendix A.1.2. Pairwise Comparison Matrix (B)—Scenario 2

Appendix A.2. Information Regarding Chilean Standards

| Category | Classification | Expected Life | Chilean Wood Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Very durable | ≥20 years | Nothofagus obliqua (Roble) Pilgerodendron uviferum (Ciprés de las Guaitecas) Fitzroya cupressoides (Alerce) |

| 2 | Durable | ≥15 years | Nothofagus alpina (Raulí) Nothofagus pumilio (Lenga) Persea lingue (Lingue) |

| 3 | Moderately durable | ≥10 years | Drimys winteri (Canelo) Nothofagus dombeyi (Coigüe) Weinmannia trichosperma (Tineo) Eucryphia cordifolia (Ulmo) |

| 4 | Few durable | ≥5 years | Araucaria araucana (Araucaria) Eucalyptus globulus (Eucalipto), Laurelia sempervirens (Laurel) Podocarpus nubigenus (Mañío) |

| 5 | Not durable | ≤5 years | Populus sp. (Álamo) Aextoxicon punctatum (Olivillo) Pinus radiata (Pino radiata) Laureliopsis philippiana (Tepa) |

| In-Service Risk Level | Use Condition | Biological Degradation Agent |

|---|---|---|

| Risk 1 (R1) | Indoor use above ground, dry environments | Insects, including subterranean termites |

| Risk 2 (R2) | Indoor use, above ground, potentially humid, poorly ventilated environments | Rot fungi and insects, including subterranean termites |

| Risk 3 (R3) | Indoor or outdoor use, above ground, exposed to weather | Rot fungi and insects, including subterranean termites |

| Risk 4 (R4) | Indoor or outdoor use, in contact with soil, with possible exposure to fresh water | Rot fungi and insects, including subterranean termites |

| Risk 5 (R5) | Indoor or outdoor use, in contact with soil, for critical structural components, exposed to fresh water | Rot fungi and insects, including subterranean termites |

| Risk 6 (R6) | Use in contact with salt water | Marine borers, rot fungi, and insects |

References

- Terraza, H.; Donoso, R.; Victorero, F.; Ibañez, D. La Construcción de Viviendas en Madera en Chile: Un Pilar Para el Desarrollo Sostenible y la Agenda de Reactivación; Terraza, H., Ed.; The World Bank: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, B.; Kim, S. Advancing the Circular Economy and Environmental Sustainability with Timber Hybrid Construction in South Korean Public Building. Build. Environ. 2024, 257, 111543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; D’Amico, B.; Pomponi, F. Whole-life Embodied Carbon in Multistory Buildings: Steel, Concrete and Timber Structures. J. Ind. Ecol. 2021, 25, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, J.; Rayburg, S.; Rodwell, J.; Neave, M. A Review of the Performance and Benefits of Mass Timber as an Alternative to Concrete and Steel for Improving the Sustainability of Structures. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasbaneh, A.T.; Sher, W.; Yeoh, D.; Yasin, M.N. Economic and Environmental Life Cycle Perspectives on Two Engineered Wood Products: Comparison of LVL and GLT Construction Materials. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 26964–26981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godinho, D.; Araújo, S.d.O.; Quilhó, T.; Diamantino, T.; Gominho, J. Thermally Modified Wood Exposed to Different Weathering Conditions: A Review. Forests 2021, 12, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodell, B.; Nicholas, D.D.; Schultz, T.P. Introduction to Wood Deterioration and Preservation. In Wood Deterioration and Preservation; Goodell, B., Nicholas, D.D., Schultz, T.P., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Poblete, P.; Gysling, J.; Alvarez, V.; Bañados, J.C.; Kahler, C.; Pardo, E.; Soto, D.; Baeza, D. Anuario Forestal 2023; INFOR: Santiago, Chile, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- NCh819:2019; Clasificación Según Riesgo de Deterioro en Servicio y Muestreo. Instituto Nacional de Normalización Madera Preservada: Santiago, Chile, 2023.

- Barbero-López, A.; Akkanen, J.; Lappalainen, R.; Peräniemi, S.; Haapala, A. Bio-Based Wood Preservatives: Their Efficiency, Leaching and Ecotoxicity Compared to a Commercial Wood Preservative. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 753, 142013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calovi, M.; Zanardi, A.; Rossi, S. Recent Advances in Bio-Based Wood Protective Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Acker, J.; Van den Bulcke, J.; Forsthuber, B.; Grüll, G. Wood Preservation and Wood Finishing. In Springer Handbook of Wood Science and Technology; Springer Handbooks: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 793–871. [Google Scholar]

- Garay, R.; Inostroza, M.; Ducaud, A. Color and Gloss Evaluation in Decorative Stain Applied to Cases of Pinus radiata Wood Treated with Copper Azole Micronized Type C. Maderas. Cienc. Tecnol. 2017, 19, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracton, A. Coatings Materials and Surface Coatings, 1st ed.; Tracton, A.A., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780429144790. [Google Scholar]

- Chronopoulos, G.; Cakmak, G.-E.; Tempany, P.; Klein, G.; Brinkmann, T.; Zerger, B.; Roudier, S. Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document on Surface Treatment Using Organic Solvents Including Preservation of Wood and Wood Products with Chemicals—Industrial Emissions Directive 2010/75/EU (Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control); Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Miranji, E.K.; Kipkemboi, P.K.; Kibet, J.K. Hazardous Organics in Wood Treatment Sites and Their Etiological Implications. J. Chem. Rev. 2022, 4, 40–66. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Response to Requests to Cancel Certain Chromated Copper Arsenate (CCA) Wood Preservative Products and Amendments to Terminate Certain Uses of Other CCA Products. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/d/03-8372/p-1 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Ali, H.R.K.; Hashim, S.M. Determining Efficacy and Persistence of the Wood Preservative Copper Chrome Arsenate Type C against The Wood Destroying Insects and Treated Wood Durability. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. A Entomol. 2019, 12, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalock, R.L.; Verdugo Alonso, M.Á.; Lee, C.S.; Lee, T.; van Loon, J.; Swart, K.; Claes, C. Manual de La Escala de Eficacia y Eficiencia Organizacional (OEES): Un Enfoque Sistemático Para Mejorar los Resultados Organizacionales; Instituto Universitario de Integración en la Comunidad: Salamanca, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tsapko, Y.T.; Horbachova, O.; Mazurchuk, S.; Tsapko, A.; Sokolenko, K.; Matviichuk, A. Determining Patterns in Reducing the Level of Bio-Destruction of Thermally Modified Timber after Applying Protective Coatings. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2021, 5, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Ning, L.; Dai, T.; Wei, W.; Ma, N.; Hong, M.; Wang, F.; You, C. Application of Bio-Based Nanopesticides for Pine Surface Retention and Penetration, Enabling Effective Control of Pine Wood Nematodes. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 502, 158009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhong, H.; Ma, E.; Liu, R. Resistance to Fungal Decay of Paraffin Wax Emulsion/Copper Azole Compound System Treated Wood. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2018, 129, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.; Garay, R. Advancing Sustainable Timber Protection: A Comparative Study of International Wood Preservation Regulations and Chile’s Framework Under Environmental, Social, and Governance and Sustainable Development Goal Perspectives. Buildings 2025, 15, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Analytic Hierarchy Process. In Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science; Gass, S.I., Fu, M.C., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 52–64. ISBN 978-1-4419-1153-7. [Google Scholar]

- NCh789:2023; Maderas—Parte 1: Durabilidad de La Madera. Instituto Nacional de Normalización: Santiago, Chile, 2023.

- May, N.; Guenther, E.; Haller, P. Environmental Indicators for the Evaluation of Wood Products in Consideration of Site-Dependent Aspects: A Review and Integrated Approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, H. Identification of Key Indicators for Sustainable Construction Materials. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 6916258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, H.; Manu, D. High Cost of Materials and Land Acquisition Problems in the Construction Industry in Ghana. Int. J. Res. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2013, 3, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Garay-Moena, R.; Castillo-Soto, M.; Fritz-Fuentes, C.; Hernández-Ortega, C. Desarrollo de Un Indicador Integrado de Sustentabilidad y Seguridad Estructural Para El Mercado de Viviendas de Madera Aplicado a Chile Central. Rev. Hábitat Sustentable 2022, 12, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay-Moena, R.; Benedetti-Ruiz, S.G. Calificación de Viviendas Prefabricadas En Madera Basada En Atributos de Cumplimiento Normativo, Complejidad y Sustentabilidad En Chile Central. Rev. Hábitat Sustentable 2024, 14, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, R.M.; Tapia, R.; Castillo, M.; Fernández, O.; Vergara, J. Habitabilidad de Edificaciones y Ranking de Discriminación Basado en Seguridad y Sustentabilidad Frente a Eventuales Desastres, Estudio de Caso: Viviendas de Madera. REDER 2018, 2, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-004506-4. [Google Scholar]

- Changotra, R.; Rajput, H.; Liu, B.; Murray, G. Occurrence, Fate, and Potential Impacts of Wood Preservatives in the Environment: Challenges and Environmentally Friendly Solutions. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Research Group on Wood Protection (IRGWP) Global Wood Protection Today. Available online: https://www.irg-wp.com/global-now.html (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Alade, A.A.; Naghizadeh, Z.; Wessels, C.B.; Stolze, H.; Militz, H. Characterizing Surface Adhesion-Related Chemical Properties of Copper Azole and Disodium Octaborate Tetrahydrate-Impregnated Eucalyptus Grandis Wood. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2023, 37, 2261–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, H.; Demir, A.; Birinci, A.U.; İlhan, O.; Demirkir, C.; Gezer, E.D. Durability and Mechanical Performance of Copper Azole-Treated Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) in-Ground-Contact Exposure for 6 Months. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Xie, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, A.; Yang, X. Effect of Copper Azole Preservative on the Surface Wettability and Interlaminar Shear Performance of Glulam Treated with Preservative. Bioresources 2024, 19, 9497–9509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I.; Zhang, G.; Bhuiyan, M.; Navaratnam, S. Circular Economy of Construction and Demolition Wood Waste—A Theoretical Framework Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, H.; Ahmadi, Z.; Hashemi, E.; Talebi, S. A Review of the Circular Economy Approach to the Construction and Demolition Wood Waste: A 4 R Principle Perspective. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 11, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janin, A.; Blais, J.-F.; Mercier, G.; Drogui, P. Optimization of a Chemical Leaching Process for Decontamination of CCA-Treated Wood. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 169, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Overview of Wood Preservative Chemicals. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/overview-wood-preservative-chemicals (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Slabohm, M.; Brischke, C.; Militz, H. The Durability of Acetylated Beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) against Wood-Destroying Basidiomycetes. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2023, 81, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandak, A.; Földvári-Nagy, E.; Poohphajai, F.; Diaz, R.H.; Gordobil, O.; Sajinčič, N.; Ponnuchamy, V.; Sandak, J. Hybrid Approach for Wood Modification: Characterization and Evaluation of Weathering Resistance of Coatings on Acetylated Wood. Coatings 2021, 11, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabohm, M.; Mai, C.; Militz, H. Bonding Acetylated Veneer for Engineered Wood Products—A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, F.; Bak, M.; Bidló, A.; Bolodár-Varga, B.; Németh, R. Biological Durability of Acetylated Hornbeam Wood with Soil Contact in Hungary. Forests 2022, 13, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, D.; Li, Y.; Kamdem, D.P. Improving the Weathering Properties of Heat-Treated Wood by Acetylation. Holzforschung 2025, 79, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yao, L.; Gong, Y.; Wang, Z. Life Cycle Assessment with Carbon Footprint Analysis in Glulam Buildings: A Review. Buildings 2025, 15, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandsson, M.; Kjellow, A.; Laurenti, R. LCA on NTR Treated Wood Decking and Other Decking Materials; Danish Technological Institute Wood and Biomaterials and IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Encinas, F.; Truffello, R.; Ubilla, M.; Aguirre-Nuñez, C.; Schueftan, A. Perceptions, Tensions, and Contradictions in Timber Construction: Insights from End-Users in a Chilean Forest City. Buildings 2024, 14, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henisz, W.; Koller, T.; Nuttall, R. Five Ways That ESG Creates Value. McKinsey Q. 2019, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Quin, F.; Ayanleye, S.; França, T.S.F.A.; Shmulsky, R.; Lim, H. Bonding Performance of Preservative-Treated Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) Posttreated with CU-Based Preservatives. For. Prod. J. 2024, 73, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.R.; Kamdem, D.P. Effect of Micronized Copper Treatments on Retention, Strength Properties, Copper Leaching and Decay Resistance of Plantation Grown Melia Dubia Cav. Wood. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2023, 81, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanleye, S.; Udele, K.; Nasir, V.; Zhang, X.; Militz, H. Durability and Protection of Mass Timber Structures: A Review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 46, 103731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivrikaya, H.; Can, A.; Tümen, İ.; Aydemir, D. Weathering Performance of Wood Treated with Copper Azole and Water Repellents. Wood Res. 2017, 62, 437–450. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Agricultura. Modifica Resolución Exenta N° 14/2019 Del Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero Que, Modifica la Resolución Exenta 1.557/2014, Que Establece Exigencias para la Autorización de Plaguicidas; Ministerio de Agricultura: Santiago, Chile, 2020.

- Walsh-Korb, Z. Sustainability in Heritage Wood Conservation: Challenges and Directions for Future Research. Forests 2021, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, C.; Ukonu, C. Why Data Can Ensure the Whole World Benefits from Impact Investing. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/01/data-impact-investing-davos24/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Nordic Wood Preservation Council. NWPC Introduction. Available online: https://www.nwpc.eu/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Duran, M. Factores de Sitio y Productividad de Pinus radiata a Escala Predial en la Región del Biobío, Chile. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia, Chile, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gavilán-Acuña, G.; Olmedo, G.F.; Mena-Quijada, P.; Guevara, M.; Barría-Knopf, B.; Watt, M.S. Reducing the Uncertainty of Radiata Pine Site Index Maps Using an Spatial Ensemble of Machine Learning Models. Forests 2021, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, M.S.; Palmer, D.J.; Leonardo, E.M.C.; Bombrun, M. Use of Advanced Modelling Methods to Estimate Radiata Pine Productivity Indices. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 479, 118557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussotti, F.; Potočić, N.; Timmermann, V.; Lehmann, M.M.; Pollastrini, M. Tree Crown Defoliation in Forest Monitoring: Concepts, Findings, and New Perspectives for a Physiological Approach in the Face of Climate Change. For. An. Int. J. For. Res. 2024, 97, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyderski, M.K.; Paź-Dyderska, S.; Jagodziński, A.M.; Puchałka, R. Shifts in Native Tree Species Distributions in Europe under Climate Change. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, K.M.; Escanferla, M.E.; Jetton, R.M.; Man, G. Important Insect and Disease Threats to United States Tree Species and Geographic Patterns of Their Potential Impacts. Forests 2019, 10, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, P.L. El Cambio Climático En Los Bosques. In Ciencia y Tecnología Forestal en la Argentina; Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2021; pp. 215–217. [Google Scholar]

- Corporación Chilena de la Madera (CORMA) Memoria 2023–2024. Available online: https://www.corma.cl/biblioteca-digital/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- León, J.; Vicuña, M.; Gil, M.; González-Mathiesen, C. Después de La Emergencia: Claves para una Recuperación Sostenible en Zonas Afectadas por Incendios en la Interfaz Urbano-Forestal, 1st ed.; Centro de Investigación para la Gestión Integrada del Riesgo de Desastres (CIGIDEN): Santiago, Chile, 2023; ISBN 978-956-14-3217-8. [Google Scholar]

- EN 350:2016; Durability of Wood and Wood-Based Products—Testing and Classification of the Durability to Biological Agents of Wood and Wood-Based Materials. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- AWPA U1-24; Use Category System: User Specification for Treated Wood. American Wood Protection Association (AWPA): Clermont, FL, USA, 2024.

| Preservative Strategy | ESG Dimension | SDG Supported | Impact Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of low-leaching formulations | Environmental | SDG 6 | Reduces contamination of groundwater and surrounding ecosystems |

| Extension of wood service life | Environmental | SDGs 12 and 13 | Reduces the frequency of replacement and lowers carbon and material footprints |

| Use of bio-based or less toxic compounds | Environmental/Social | SDGs 3 and 12 | Minimizes worker exposure and consumer health risks; supports circular economy |

| Transparent product labeling and certifications | Governance | SDGs 16 and 17 | Improves trust, facilitates compliance, and fosters stakeholder collaboration |

| Support for local treatment facilities and training | Social/Governance | SDG 8 | Enhances decent employment and promotes inclusive industry development |

| Attribute | Level 1 | Description | Likert Scale 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protection Treatment (PT) | Low | Wood protection is achieved by design-based protection, enveloping and surface treatments, and anti-stain baths. | 1 |

| Moderate | Application of preservative impregnation for various levels of in-service risk, including chemical modification treatments. | 3 | |

| High | Cumulative combinations of the above solutions, incorporating sustainability into the approach. | 5 | |

| Wood Durability (WD) | Low | Wood protection according to intrinsic durability, e.g., less durable Pinus radiata in Chile. | 1 |

| Moderate | Wood protection by applying chemically modified wood. | 3 | |

| High | Wood protection by using durable native woods. | 5 | |

|

In-Service Risk

(RS) | Low | Wood protection must match the appropriate risk class for its use. If risks are not addressed, the treatment’s effectiveness is compromised. | 1 |

| Moderate | Current wood protection measures do not adequately align with the risk classification and require improvement. While the wood is preserved, it lacks a surface treatment, making it vulnerable to abiotic factors. Thus, enhancements are necessary. | 3 | |

| High | Wood protection has analyzed the factors contributing to damage and assessed risk classifications across various service conditions. The goal was to identify the most effective option to minimize environmental impact, with a focus on sustainability for risk classes 1 to 6, including marine environments. | 5 | |

|

Sustainability

(S) | Low | Utilizes bio-based compounds that effectively resist biological organisms, offering short-term protection against fungi, insects, and other wood-degrading organisms (1 year or less). | 1 |

| Moderate | The treatment has proven its durability in performance tests, requiring periodic reapplication every one to two years or using in situ reapplication technology. It is characterized by ease of application and the minimal time and resources needed for protection. | 3 | |

| High | The treatment is cost-effective in terms of duration and protection. It has a low environmental impact due to its low toxicity, minimal leaching, and biodegradability under continuous water exposure throughout its service period, demonstrating effective. | 5 |

| Attribute | Symbol | Scenario 1 (%) | Scenario 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protection treatment (PT) | Xi | 50 | 20 |

| Wood durability (WD) | Yi | 15 | 10 |

| In-Service Risk (RS) | Zi | 15 | 10 |

| Sustainability (S) | Ui | 20 | 60 |

| Level of Compliance | WPSI (%) |

|---|---|

| High | (75–100) |

| Medium | (50–75) |

| Low | (1–50) |

| Wood Preservative | Active Ingredient (A.I) Concentration (%) | Risk Class (Uses) 1 | Retention (kg A.I/m3) | Product Retention (kg Product/m3) | Cost 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCA | 60 | Risk levels 1, 2, 3 (construction) | 4 | 6.67 | 34 USD/m3 (5 USD/kg) |

| Risk level 4 (agricultural use) | 6.4 | 10.67 | 54 USD/m3 (5 USD/kg) | ||

| Risk level 5 (utility poles) | 9.6 | 16 | 80 USD/m3 (5 USD/kg) | ||

| μCA | 26 | Risk levels 1, 2, 3 (construction) | 1 | 3.85 | 33 USD/m3 (8.5 USD/kg) |

| Risk level 4 (agricultural use) | 2.4 | 9.23 | 79 USD/m3 (8.5 USD/kg) | ||

| Risk level 5 (utility poles) | 3.7 | 14.23 | 121 USD/m3 (8.5 USD/kg) |

| ESG Criteria | How Advanced Wood Preservatives Score | Areas Where Chile Must Focus on Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| E Emissions/leaching | Non-metal chemistries and modification routes cut Cr/As runoff, align with SDGs 6 and 13. | Fast-track μCA (Cu-azole) in class 4 uses; pilot acetylated radiata pine. |

| S Worker and end-user health | New generation preservatives (such as MCA, μCu, ACQ) avoiding the use of dangerous heavy metals, lowering VOCs → SDG 3 benefits. | Mandate safer products in housing; launch public education to shift consumer demand. |

| G Regulatory and reputational risk | EU-style performance testing + transparent LCA data reduces future liability. | Move from “active-substance list” to performance-based approvals; integrate third-party certification (e.g., NWPC model). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fritz, C.; Ruiz, M.; Garay, R. Development and Application of a Sustainability Indicator (WPSI) for Wood Preservative Treatments in Chile. Forests 2025, 16, 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16081351

Fritz C, Ruiz M, Garay R. Development and Application of a Sustainability Indicator (WPSI) for Wood Preservative Treatments in Chile. Forests. 2025; 16(8):1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16081351

Chicago/Turabian StyleFritz, Consuelo, Micaela Ruiz, and Rosemarie Garay. 2025. "Development and Application of a Sustainability Indicator (WPSI) for Wood Preservative Treatments in Chile" Forests 16, no. 8: 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16081351

APA StyleFritz, C., Ruiz, M., & Garay, R. (2025). Development and Application of a Sustainability Indicator (WPSI) for Wood Preservative Treatments in Chile. Forests, 16(8), 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16081351