4.1. Fine Issuance

Figure 4 reports the variation in the issuing of fines for flora related infractions in Mato Grosso between 2004 and 2012, the fining intensity, and the correlation coefficients between the number of infractions, their value, and deforestation in the state.

Table 2 provides the summary statistics.

There is a strong negative correlation between fines directly associated with forest loss (deforestation/fire) and deforestation, both in terms of number of fines and value. The introduction of the DETER system likely increased the probability of detecting and issuing fines by making the fast dispatch of law enforcing agent to affected areas possible. With the creation of ICB as the implementer of the national conservation units policy, IBAMA ceded a large number of its staff to the new agency, putting additional strain on the already over-loaded remaining staff (Interview with IBAMA staff in November 2014); the increase in fines was not associated with an increase in the number of inspecting staff, but rather a better allocation of the limited resources.

It is also possible to observe an increase in the fining intensity as measured by the ratio between the value of fines for deforestation and fire and the total deforestation. This is likely a reflection of changes related to the regulation of the Environmental Crimes Law. In revoking Decree N. 3179/1999, Decree N. 6514/2008 not only increased the value of fines per hectare of destroyed forest, it also increased the period for recidivism from 3 to 5 years. The extent of the increase in pecuniary punishment was considerable, with fines for deforestation in areas of permanent protection, for example, being raised from R$1,000 to R$ 5,000 per hectare.

Finally, the imposition of high fines for possession or transportation of wood or sawn timber without proper documentation is often reported in the Brazilian media as an example of forest law enforcement efforts in the Amazon. The total value of fines for this kind of infraction is also negatively correlated with current and future deforestation. The positive coefficient between the number of fines for irregular wood and current deforestation reflects the expected increase in the number of fines issued as a response to higher deforestation.

4.2. Fine collection

In order to test Hypothesis 1,

Figure 5 reports the statuses of fines issued between 2004 and 2012 as percentages of the total number of fines issued yearly and their respective values, as of August 2015. Collection rates decrease as the issuance of fines become more recent; in terms of amount, the percentage of values effectively collected is particularly minor, at less than 1%, even for fines issued at the beginning of the study period. Such a low percentage is likely to reduce the deterrence effect of fines on illegal deforestation, since the negative economic consequences of the infraction are not immediately faced by law offenders.

When an offender debt is overdue, the status of the fine changes to active debt, and IBAMA is then able to take legal action to collect the values issued. The time taken to collect the fine depends on the pace of the ruling in common courts of justice, renowned in Brazil for their slow ruling speed.

With regard to deforestation/fire and irregular wood related fines, almost 40% fell into the category of judicial proceedings in the years 2004 and 2005. This category is for infractions whose perpetrators took the whole fining process to court outside IBAMA on the grounds that the agency did not conform to legal procedures. Although the reason for such a high percentage is unclear, it may well be associated with the 2005 Operação Curupira, an anti-corruption crackdown operation that targeted a large scheme of illegal forest exploitation activity. This operation resulted not only in the arrests of IBAMA’s Mato Grosso branch superintendent and the state environmental agency chief secretary, but also in the entire overhaul of Mato Grosso environmental agency. It should be noted that the pattern of low collection of the fines in these two categories is similar to the general trend.

That a large percentage of the statuses in all graphs can be classified as defense analysis (under appeal) indicates that the effects of initiatives taken by IBAMA and the Ministry of Environment to speed up the process have yet to materialize. Among the initiatives that have been agreed upon is Decree N. 6154/2008, which reduces the number of administrative appeals from four to two. Once the notice of infraction has been confirmed, the law offender has a 20-day window to appeal to IBAMA, and if the appeal is rejected, the only course of action open to the offender is to further appeal to CONAMA (National Council on Environment), a deliberative body that decides on the formulation and implementation of the national environmental policy.

The above analysis indicates that although technological innovations have been introduced to increase the probability of detecting illegal deforestation, and that changes in legislation allow infractions to be more severely punished (at least nominally), the Brazilian government is yet to achieve effective collection of the fines issued both in terms of values as well as in terms of time passed since the infractions. The extremely low collection rate of less than 1% thus leads us to reject Hypothesis 1. That is, it can be concluded that the increase in fining intensity observed in the 2004–2012 period was not accompanied by higher collection rates of the fines.

When considering engaging in illegal forest conversion, it is likely that rural producers discount the fines to some extent due to the long time they have until payment is required. Therefore, when assessing the impact of fines on deforestation, the fact that their deterrent effect is lower than their nominal value must be kept in mind. In the subsequent regression analyses, all fines for deforestation/fire and illegal wood infractions are considered as proxies for detection rates, but their value is discounted based on the percentages in the categories “convicted/paid” and “instalments” when considering fine intensity.

4.3. The Deforestation Deterrence Impact of Embargoes

Table 3 summarizes the impact of embargoes imposed for forest-related infractions in Mato Grosso in order to assess Hypothesis 2. From a total 3426 embargoed properties, 721 intersected with INCRA’s georeferenced land cadaster. This land cadaster, although not complete, is the most reliable database of perimeters of the private properties in Mato Grosso, as it is compiled in a way that prevents the overlapping of the polygons representing the properties. The implementation of the land cadaster started in 2004 in Mato Gross, and as of February 2015, about 43.7% of the area of the state was identified as privately owned. Another 37.9% are thought to be privately owned but remained without georeferencing ([

49], unpublished). It is thus possible that many properties that became target of embargoes are yet to provide their GIS information to INCRA.

By the time of the imposition of the embargo, an average 48.5% of the property area on embargoed properties remained covered with forest, which falls short of the minimum 80% required by Brazilian forest law. Nevertheless, by 2013 the remaining forest in the embargoed properties had decreased by just one percentage point to 47.5%, indicating that embargoes had deterred deforestation within the borders of the properties.

Of the 686 embargoed properties with remaining forest, the embargo was highly effective in preventing further forest loss in 495; no forest loss occurred after the imposition of the embargo. The embargoes were partially effective in preventing forest loss on 21.9% of the properties with remaining forest, and this partial effectiveness can be divided in two types: embargoed properties where forest loss occurred in the year immediately after the embargo was put into effect but not afterwards, and embargoed properties where no forest loss occurred in the year immediately after the embargo was put into effect, but afterwards. In 96 properties, embargo did not prevent further forest loss.

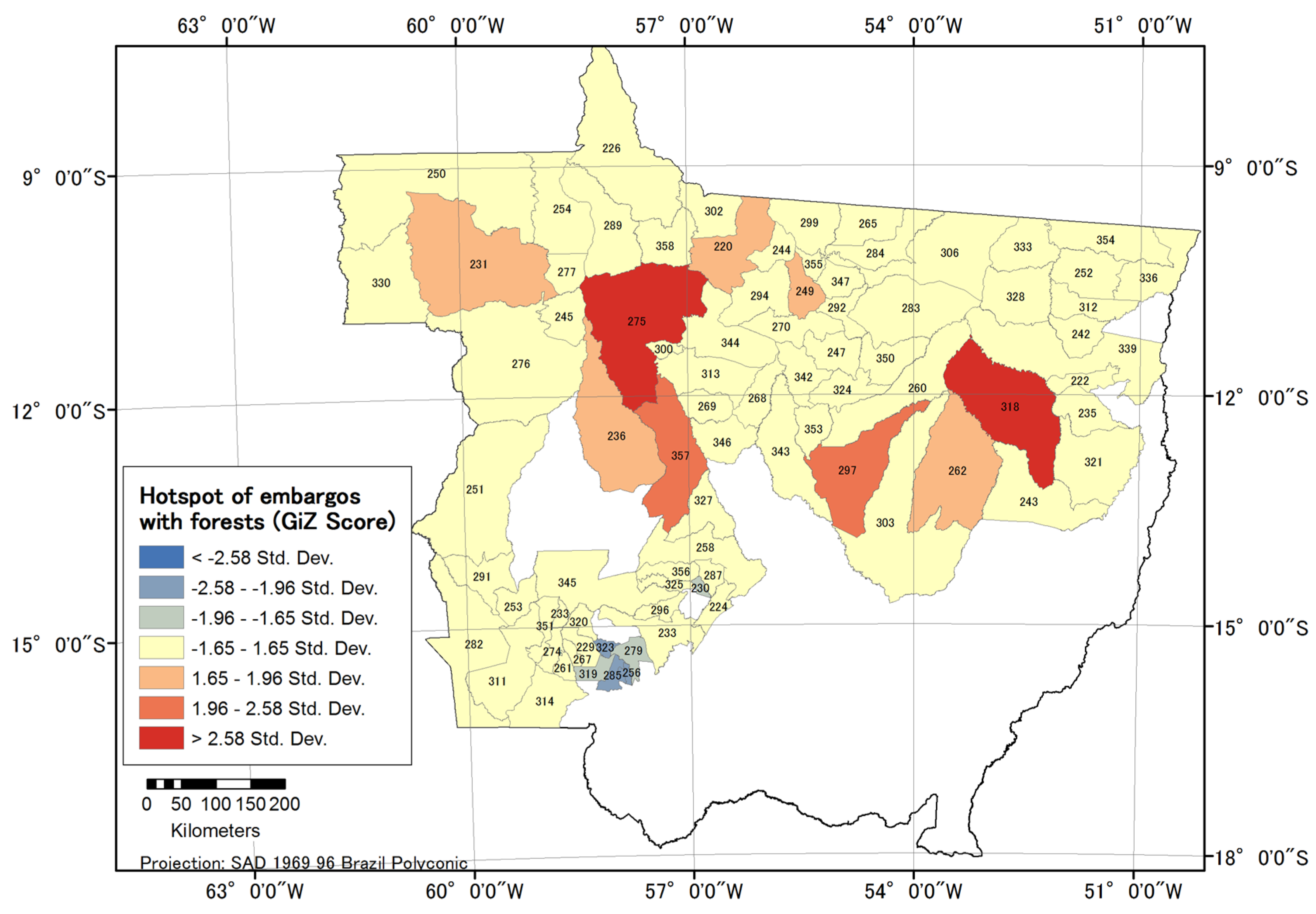

In

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, hot spot analysis maps show respectively the spatial distribution of embargoes on properties with remaining forest, the effectiveness and their ineffectiveness. The existence of overlapping hot spots of embargoes on properties with remaining forest and hot spots of effective embargoes indicates that the characteristics of these areas have an impact on deforestation. The northwest of the state is a relatively remote area with a relatively poor transportation infrastructure. The three municipalities in the central north east (297, 262, 328) are located in a region with dynamic soybean and beef production, and with a large amount of terrain within the Xingu National Park (indigenous land). The municipality of Colider (249) stands out as a place where despite the large number of embargoes on property with remaining forests, the embargoes seem to have had limited effect. While the reason for this remains unclear, it may well be related to the high incidence of socio-environmental conflicts in this part of Mato Grosso, where different levels of government have reported difficulty enforcing various types of regulations [

50].

With the exception of Colider, it was observed that embargoes were mostly effective in deterring further forest loss within the borders of the embargoed property, and as such it can be concluded that they are, as suggested by Hypothesis 2, an effective form of sanction against further deforestation.

4.5. The Impact of Administrative Sanctions on Deforestation

This section reports and discusses regression analyses results to test Hypothesis 3; that is, that there is a negative correlation between deforestation and effectively implemented administrative sanctions, namely fines, embargoed rural properties and confiscation events involving vehicles. The explanatory variables used throughout the regressions are summarized in

Table 5. In addition to the considerations for the choice of variables explained in

Section 3.2, the variable Adjusted Fine Intensity def/fire/wood refers to the total value of fines for deforestation, forest fire, and irregular wood possession/transportation in a given year divided by the total deforestation of the given year, times the percentage of the value of those fines that have effectively been collected (paid) or are being collected. These variables are indicated in

Figure 5.

The results of regressions with three types of administrative sanctions are indicated in

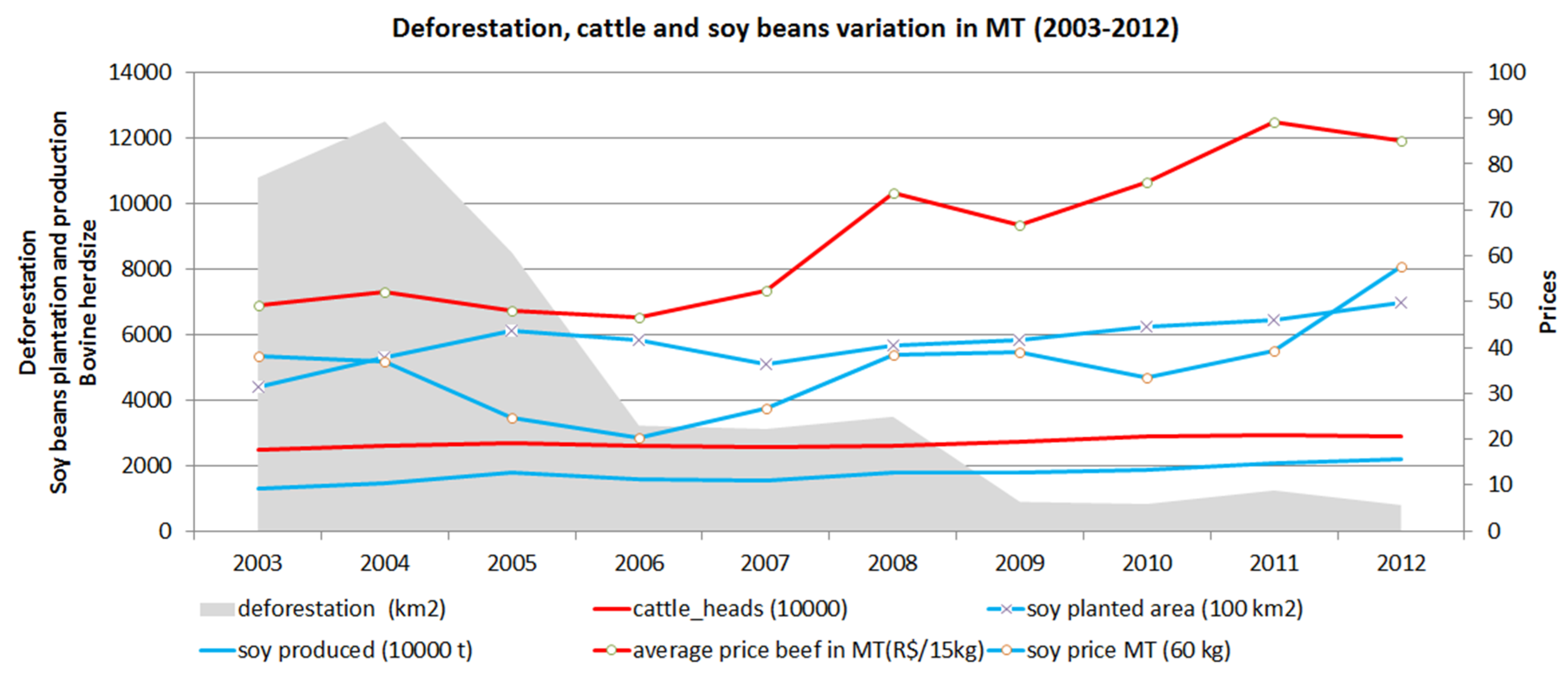

Table 6. The regressions also take the establishment of new protected areas as deforestation deterrence measures into account, along with the bovine herd size and soy plantation as deforestation causative factors. It should be noted that the effect of rainfall on deforestation has also been taken into account. In the OLS model, soy expansion is strongly correlated with deforestation. For example, a 10% increase in the area of plantation is associated with a 1.1% increase in deforestation when all other independent variables are held constant. Interestingly, cattle expansion, while having a positive coefficient, did not show any statistical significance.

The imposition of embargoes and the fine intensity are strongly inversely correlated to deforestation. An increase in 10% in the number of embargoes is associated with a deforestation decrease of 4.1%, and a similar increase of 10% in the value fines per hectare is associated with a deforestation decrease of 2.5%. In section 4.2 it was shown that the effective collection of fines issued during the study period remained low. Therefore, we interpret the coefficient −0.2597 of the Fine Intensity variable as the potential impact that fines could have had on deforestation if they were fully collected.

The statistically significant positive coefficient of infractions is likely a result of endogeneity, as the number of fines issued likely increases when there is higher deforestation.

The Fixed Effect (1) model controls for the differences across municipalities in the state. A PM dummy was added to this model to account for certain municipalities in the state that were added to IBAMA’s priority municipalities list since 2008. It should be noted that municipalities on this list are subject to more intense monitoring and control efforts. The role of cattle and soy on deforestation in this model differs significantly from that of the OLS model; while soy is no longer statistically significant, cattle ranching shows a strong negative correlation with deforestation. While this may seem counterintuitive at first, when seen in the light that bovine herd size was used as a proxy for cattle ranching expansion due to the unavailability of pasture land data, this finding may highlight a process of increasing occupancy rate.

As observed in the OLS, the issuing of fines in the Fixed Effect (1) model has a strong positive correlation with deforestation. On the other hand, in addition to fine intensity and embargoes, the confiscation of vehicles was also statistically significant, and had the expected negative impact on deforestation. When controlling for the individual effect of municipalities, the negative impact of a 10% increase in the percentage of protected areas in the state was found to result in a 1.5% decrease in deforestation. The large coefficient found for priority municipalities highlights the effectiveness of the additional monitoring and controls in these municipalities.

In the second fixed effect model, the possible endogeneity between the increase in the number of fines and deforestation, as well as the imperfect collection of fines were considered. Toward this means, the number of infractions was subject to a one year lag in order to show the effect of the number of fines issued in the previous year on deforestation of the following year. In addition, the fine intensity variable was substituted for an adjusted fine intensity variable to provide a more accurate assessment of the real impact of the magnitude of fines on deforestation. In this model, the results with regard to deforestation causative factors show that soy expansion is again statistically significant to explain increasing deforestation, and cattle expansion retains its statistically significant negative coefficient observed in the first fixed effect model.

With regard to the effectiveness of fines, the introduction of the two new variables provides reassuring results. First, the number of fines issued became negatively related to deforestation. In this situation, rather than having the number of fines increase as a response to higher deforestation, the increase in fines in the recent past is associated with a decrease in deforestation. A 10% increase in the issuing of fines in the previous year is associated with a 1.8% decrease in deforestation that year. Second, the adjusted fine intensity was also statistically significant to explain variations in deforestation. The negative coefficient of 0.131 implies that a 10% increase in effectively collected fine intensity is associated with a 1.3% decrease in deforestation. Although this figure may seem small, it would have amount to approximately 4570 hectares of avoided deforestation in 2008, for example.

As was the case with the Fixed Effect (1) model, the confiscation variable is statistically significant in the Fixed Effect (2) model, and has the expected negative coefficient. While the limitations of directly associating the location of the confiscation with the location of the deforestation must be acknowledged, the confiscations appear to have a direct impact on the ability to conduct deforestation by depriving offenders of the means to continue illegal deforestation.

In the Fixed Effect (2) model, the variance inflation factors indicate that overall there is no autocorrelation between the variables. Furthermore, the model is capable of explaining approximately 70% of the variation in deforestation in the selected municipalities in Mato Grosso. These characteristics of the model, along with the statistically significant negative impact on deforestation shown by the sanctions variables give credence to hypothesis 3; that is, there is a negative correlation between deforestation and effectively implemented administrative sanctions, namely fines, embargoed rural properties and confiscation events involving vehicles.

However, is this correlation a causal one? Given that increased regulatory vigor since 2004 coincided with a decrease in deforestation, one is likely to ask what would have happened in the absence strengthened illegal deforestation control mechanisms. Would a similar deforestation decrease be observed, would there be no change, or would deforestation actually increase? Although counterfactuals are one of the central elements for any type of policy impact evaluation that aims to go further than being a general description of a process [

51,

52], the present research does not provide such explicit counterfactuals that would bolster the argument that the decrease in deforestation observed is resulted from improvements in deforestation control measures.

One of the main difficulties in providing counterfactuals in the present study lies in the current low understanding of the working of fines as an imperfect deforestation deterrent mechanism. The logic behind the effectiveness of embargoes and confiscations lies in negation of trade opportunity, increased monitoring and the removal of means used for deforestation. On the other hand, why would a producer be more law abiding in a situation where the likelihood of more and heavier fines is higher, but their actual collection continues to be extremely low? Increased knowledge on how the low collection of fines affected and affects land owners behavior in Mato Grosso is a topic that demands urgent attention by the academic literature in order to accurately evaluate the Brazilian government deforestation control efforts.