Abstract

Cellular immunity against rotavirus in children is incompletely understood. This review describes the current understanding of T-cell immunity to rotavirus in children. A systematic literature search was conducted in Embase, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Global Health databases using a combination of “t-cell”, “rotavirus” and “child” keywords to extract data from relevant articles published from January 1973 to March 2020. Only seventeen articles were identified. Rotavirus-specific T-cell immunity in children develops and broadens reactivity with increasing age. Whilst occurring in close association with antibody responses, T-cell responses are more transient but can occur in absence of detectable antibody responses. Rotavirus-induced T-cell immunity is largely of the gut homing phenotype and predominantly involves Th1 and cytotoxic subsets that may be influenced by IL-10 Tregs. However, rotavirus-specific T-cell responses in children are generally of low frequencies in peripheral blood and are limited in comparison to other infecting pathogens and in adults. The available research reviewed here characterizes the T-cell immune response in children. There is a need for further research investigating the protective associations of rotavirus-specific T-cell responses against infection or vaccination and the standardization of rotavirus-specific T-cells assays in children.

1. Introduction

Rotavirus is the leading cause of life-threatening diarrhea among young children, particularly in those below five years of age [1,2]. Globally, rotavirus has been responsible for approximately 258 million diarrhea episodes and an estimated 128,515 diarrhea deaths in this population with the largest burden within Sub-Saharan Africa [3]. Fortunately, rotavirus vaccines are widely available and have significantly contributed to reductions in rotavirus-associated diarrhea morbidity and mortality globally [4,5,6]. However, despite being discovered nearly half a century ago in 1973 and more than a decade since vaccine introduction, immune mechanisms, and correlates of protection against rotavirus remain poorly understood [7].

In humans, rotavirus is transmitted via a fecal-oral route and is known to predominantly infect and replicate in mature enterocytes of the intestinal epithelium inducing innate and adaptive humoral and cellular immune responses [8]. In children, repeated rotavirus infection leads to a lower likelihood of subsequent rotavirus infections and reduced occurrence of moderate to severe diarrheal disease suggesting the development of immune memory [9]. This acquired, non-sterilizing immunity is derived from a combination of gut secretory and humoral antibody and cell-mediated immune effectors with neutralizing antibodies directed against the viral capsid proteins and viral epitope recognition by T-cells thought to play an important role in protection [8]. However, immune parameters correlating with protection against rotavirus in humans are yet to be demonstrated [10].

Rotavirus-specific antibodies are well documented and frequently studied in children as immune markers of previous infection or vaccination [11]. However, even though they are recognized as being important for protection, it is generally appreciated that these antibody markers are sub-optimal correlates of protection [12,13]. In contrast, there is sparse data on the underlying T-cell immune responses to rotavirus infection or vaccination, particularly in children, and even fewer still have studied the role of this T-cell immunity in protection against rotavirus. The current understanding of rotavirus T-cell mediated immunity has for the most part been achieved through studies in animal models which have shown that T-cells have crucial roles in suppression of rotavirus replication, clearance of infection, and generation of antibody responses associated with protection [10,14,15,16].

As rotavirus remains a cause of high morbidity and mortality in children, especially in the developing world [3], it is necessary to fully understand the immune mechanisms underlying protection. Improved knowledge on T-cell-mediated rotavirus immunity can inform vaccine development and is particularly important considering the sub-optimal antibody immune correlates and the consistent observation of markedly lower vaccine immunogenicity and efficacy in children within high rotavirus burden regions [17]. We, therefore, conducted a systematic review of literature on T-cell responses to rotavirus in children to consolidate currently available knowledge on the characteristics of T-cell immunity to rotavirus in this population including its association with the antibody responses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist (Table S1) in the preparation of the systematic review manuscript [18]. The literature search was conducted in Embase (1947 to March 2020), MEDLINE (1946 to March 2020), Web of Science (1970 to 2020), and Global Health (1910 to week 9 2020) electronic databases using a combination of “T-cell”, “rotavirus” and “child” keywords to identify relevant articles (File S1).

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Studies included in this review were those that were primary research, were conducted among children or used child-derived samples in any region of the world, reported T-cell immune responses to rotavirus, had full English text available and had rotavirus as the main focus of the study. There was no restriction to study design, but we restricted selection to articles published after 1973, the year rotavirus was discovered.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

We excluded studies that did not include children or child-derived samples, did not report T-cell responses against rotavirus, or had no English full text available. Non-primary research including review articles and conference abstracts were also excluded.

2.4. T-Cell Responses

The T-cell responses considered in the systematic review were T-cell quantity (counts, ratios, frequencies), phenotype (activation, cell surface markers, epitopes) function (cytokine secretion), activity (proliferation), and kinetics (pre and post-infection or vaccination, durability) for all CD4 and CD8 T-cells subsets.

2.5. Study Selection and Data Extraction

EndNote reference manager software was used to remove duplicate articles identified from the search strategy. The resulting unique articles were imported into Rayyan web-tool software for additional duplicate identification and article selection. Three reviewers (NML, CC, MS) independently selected potentially eligible articles by screening the title and abstract of all unique articles for the keywords using the Rayyan web-tool software. Full texts of articles selected by all three reviewers combined were retrieved and assessed for eligibility using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles concordantly selected as eligible by the three reviewers were included in the review and those concordantly rejected were excluded from the review. Discordance in selection was discussed and re-assessed together by all three reviewers until a consensus on inclusion or exclusion was made. Data were extracted into an excel sheet to capture information on the author, year of publication, study location, study design, characteristics of the child population, sample size, rotavirus context (rotavirus infection or vaccination), T-cell responses, and laboratory methods used for measures of T-cell immunity.

2.6. Quality Assessment and Data Synthesis

We reviewed published articles of similar nature to our systematic review to identify potential appraisal tools and we adapted a recently published quality assessment tool [19] and quality level thresholds (0% to 39% = low, 40% to 69% = moderate, and 70% to 100% = high) [20] for our critical appraisal (Table S2). One author (NML) conducted the quality assessment which was reviewed by two other authors (SB and ONC). Due to the wide heterogeneity in laboratory methodology and reported T-cell response across the studies included in the systematic review, formal quantitative meta-analysis was not conducted, and results were presented in a thematic narrative format.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search Results

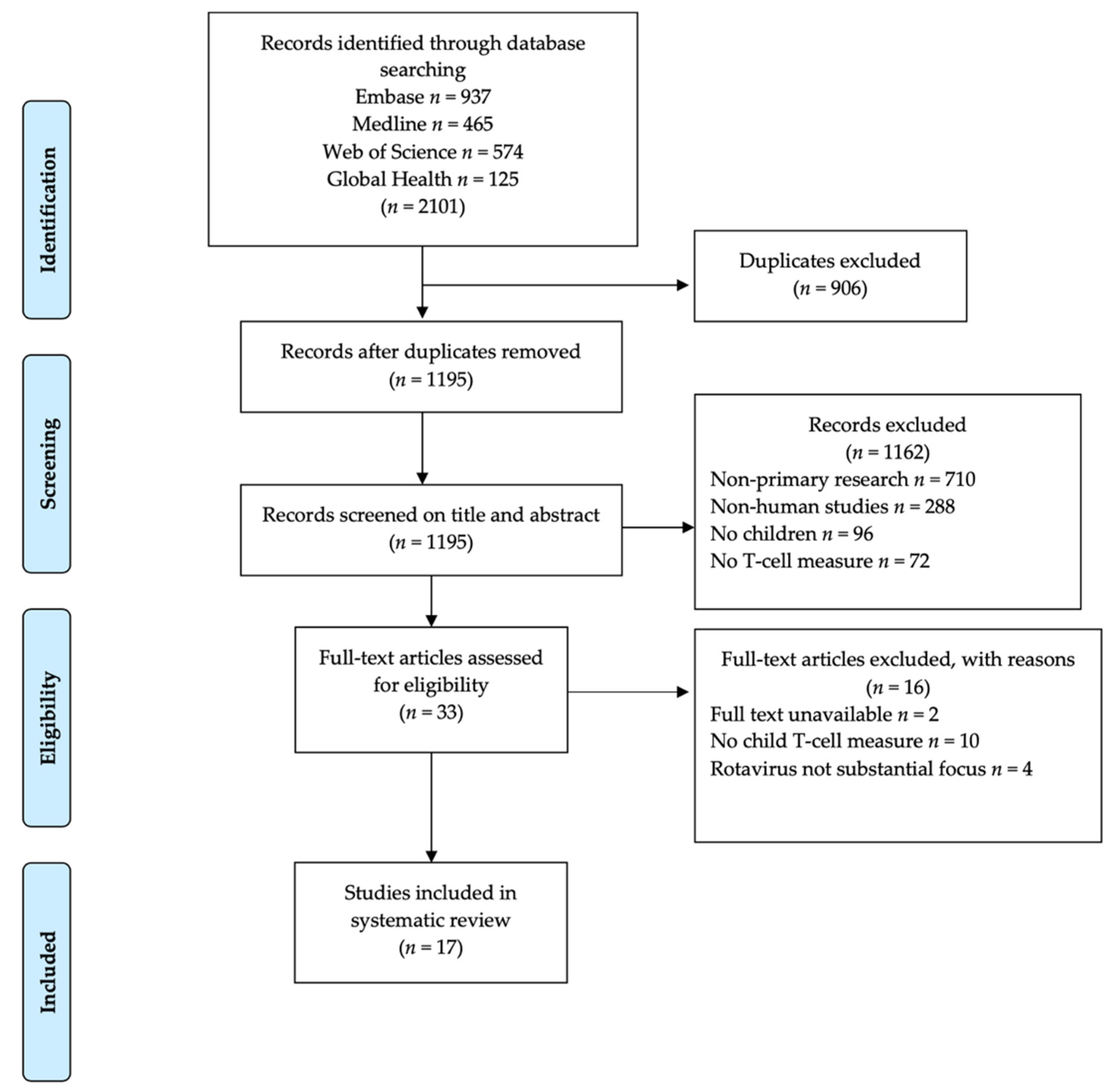

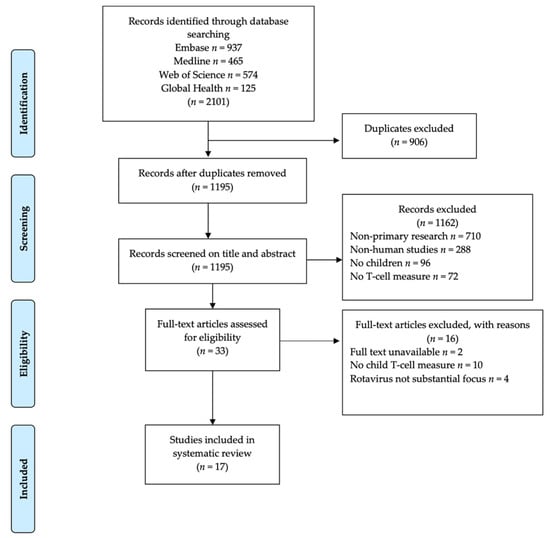

Articles retrieved from the literature search comprised 937 from Embase, 465 from MEDLINE, 574 from Web of Science, and 125 from Global Health electronic databases giving a total of 2101 articles identified. After the removal of 906 duplicate articles, a resulting total of 1195 articles were screened for eligibility based on title and abstract and an additional 1162 articles were excluded because they were non-primary research (n = 710), were not about rotavirus in humans (n = 288,) did not include children (n = 96), did not report T-cell responses (n = 72). The remaining 33 articles underwent further screening for eligibility by full text based on set inclusion criteria. After full-text screening, a further 16 articles were excluded because they did not have full text available to the reviewers (n = 2), did not report T-cell responses for children (n = 10), and rotavirus was not the main focus (n = 4). This resulted in 17 articles that met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review as summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature search results and article selection process.

3.2. Characteristics of Articles Included in Systematic Review

Among the seventeen studies included in the systematic review, the earliest study identified was published in 1988 and the latest in 2018. Most of the studies were conducted among children in the Americas (9/17) followed equally by Europe (3/17) and Asia (3/17) while the least number of studies (2/17) was conducted among African children. Ten studies reported T-cell immunity in the context of rotavirus infection, two studies reported T-cell responses to rotavirus vaccination, and five studies reported rotavirus-specific T-cell response in healthy children. Laboratory methods used to measure T-cell responses varied across studies and included flow cytometry, lymphoproliferation, microscopy, indirect fluorescence microscopy, gene microarray, and enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assays. Different types of T-cell outcomes in response to mitogen, human rotavirus, and non-human rotavirus antigens were reported across studies. More detailed characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review are as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review.

3.3. Quality Assessment of Individual Studies

Of the included studies, 15/17 (88.2%) were observational studies while only 2/17 (11.8%) made use of experimental designs in the form of randomized controlled trials (Table 1). Using our adapted appraisal tool and threshold definitions of study quality, most articles were of moderate quality 11/17 (65%). The remaining 6/17 (35%) articles were appraised as high-quality articles of which the majority 5/6 (83%) were published in more recent years (Table 1). Most studies included in the review provided adequate information on research gaps around immunity to rotavirus, including research questions and rationales for the study of T-cell-specific responses to rotavirus. However, there was generally poor methodological reporting for most studies with minimal to no detailed information provided on the exact study design employed, calculations, and assumptions for stated samples sizes or specification of inclusion and exclusion criteria for children or child-derived samples included in the studies. In most studies, there was also a poor presentation of participant or sample flow from recruitment to laboratory testing results as well as little to no information on children’s background characteristics (Table S2).

3.4. T-Cell Proliferation against Rotavirus Develops and Broadens Reactivity with Increasing Age

Children can mount detectable T-cell proliferation to different strains of rotavirus after in-vitro stimulation which is associated with age. As shown in Table 2, six studies reported induction of T-cell proliferation against human and non-human rotavirus strains and its relationship with the child’s age. Children with acute rotavirus diarrhea had more positive and significantly higher T-cell proliferation to rotavirus antigen compared to healthy children. Among healthy children, T-cell proliferation was absent in newborns, minimally present in children aged <6 months but became more commonly detected in older age groups of children [22,25,26,28,37]. In contrast to this, however, one study also reported evidence of detectable T-cell proliferation in newborn children [28]. In healthy children, although T-cell proliferation to a human rotavirus strain was observed to be stronger than that against a bovine rotavirus strain, a positive correlation of T-cell reactivity was observed between the strains [26]. By the age of 2 years old and beyond, most children had developed T-cell reactivity against two strains of human rotavirus and against rhesus rotavirus strains [28]. However, T-cell proliferation against two different human rotavirus strains has also been observed among children aged <2 years old with acute and convalescent rotavirus diarrhea caused by different infecting rotavirus strains [29].

Table 2.

Relationship between rotavirus T-cell proliferation and child age.

3.5. Rotavirus T-Cell Proliferation and Frequency Coincides with Antibody Responses but Is More Transient

Six studies reported T-cell immunity in association with rotavirus antibody responses as shown in Table 3. T-cell responses were observed more frequently in rotavirus antibody seropositive than seronegative children and among secondary than primary infections indicating that both memory T-cell and antibody responses are induced by rotavirus exposure and built from repeated exposure [25,26,31]. The strength and magnitude of T-cell responses occurred in very close association with the antibody response. Makela et al. showed that generally, lower antibody titers to rotavirus were accompanied by minimal or absent T-cell responses while increased antibody responses were associated with stronger T-cell responses. However, strong T-cell immunity was also observed in the absence of increasing antibody responses in a single child in this study and although firm conclusions cannot be made based on this lone observation, it highlights the need to detect both antibody and cellular responses in assessing rotavirus immunity [26]. Compared to antibodies that persisted long after infection, T-cell responses were more transient, detectable two to eight weeks and three to five months post-infection but declining as early as 5 months to nearly undetectable levels within 12 months post rotavirus exposure [26,29]. However, both T-cell and antibody responses were minimal during acute rotavirus infection but more frequent during convalescence [29]. Unlike antibodies present at birth, T-cell immunity was generally absent in early infancy (<6 months) developing much later in infancy and may therefore be a better indicator of active infant immunity than antibodies and distinguish from passive maternal immunity in the very young infants [28]. Both T-cell and antibody responses can be mounted against different infecting rotavirus strains indicating an inability to clearly distinguish rotavirus P and G serotypes [29]. Rotavirus-specific CD4 T-cells are positively associated with antibody responses, while regulatory T-cells may either have a positive or negative association with the antibody response to rotavirus [35]. One study among T-cell deficient children further emphasized intimate associations between T-cell immunity and antibody response in the context of clearance of rotavirus infection. Wood et al. described chronic rotavirus infection in two children with congenital T-cell deficiency [36]. In a child with cartilage hair hypoplasia associated T-cell deficiency and acute rotavirus diarrhea, no serum antibody immune response to rotavirus was detected. Likewise, no significant proliferative response to rotavirus was observed ~1 year after the onset of diarrhea and diarrhea persisted over an 18-month period characterized by poor weight gain and failure for the child to thrive despite treatment. In the same study, a second child with CHARGE congenital abnormalities and DiGeorge syndrome associated T-cell deficiency who was infected with rotavirus, the rotavirus IgG antibody response was undetectable two months after rotavirus infection and despite treatment, this child failed to thrive and died at 5 months old.

Table 3.

Rotavirus T-cell proliferation, frequencies, and phenotypes in relation to an antibody response.

3.6. CD4 and CD8 T-Cells Are of Low Circulating Frequency in Acute Rotavirus

Five studies reported a lower circulating frequency of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells in response to acute rotavirus infection. In one study, while healthy children had normal proportions of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell subsets, children with acute rotavirus diarrhea had selectively lowered CD4+ T-cell proportion and a low CD4+:CD8+ T-cell ratio [22]. A case study of a single child with rotavirus diarrhea showed a depressed CD4+ T-cell frequency and CD4+:CD8+ ratio in an acute phase that persisted up to one-month post-infection but normalized by convalescent period [23]. In another two studies close to half of the children with rotavirus diarrhea had absolute lymphopenia compared to children with or without previous rotavirus exposure but with non-rotavirus diarrhea and the majority of children with acute (<7 days after the onset of illness) rotavirus diarrhea had total whole blood lymphocyte counts less than the lower limit of the normal count range in healthy children [27,34]. Additionally, among children with previous rotavirus exposure and those with rotavirus diarrhea, few had detectable cytokine-producing rotavirus-specific CD4 or CD8 T-cells [27]. Likewise, flow cytometry and gene expression T-cell analysis of children with rotavirus diarrhea revealed significantly lower mean frequencies of CD4+ and αβ+CD4+ T-cells, CD8+ and αβ+CD8+ T-cells and T-cell associated gene expression in children with rotavirus diarrhea in the acute phase than in healthy controls. In the convalescent phase, however, the frequencies of these T-cell populations significantly increased to similar levels observed in healthy children. Exceptionally, one child with rotavirus diarrhea was observed to have a minimal reduction in CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell frequencies in the acute stage but had a severe reduction in CD4 and CD8 T-cell subsets at convalescence [34]. Among vaccinated children, rotavirus antigen-experienced CD4 T-cells were detected in low frequencies two weeks post-vaccination [31]. Summary findings of these studies are outlined in Table 4.

Table 4.

Proliferative, Helper, and cytotoxic T-cell frequency to rotavirus in children compared to adults and other stimulants.

3.7. Proliferative, Helper and Cytotoxic T-Cells Profiles to Rotavirus Differ in Children Compared to Adults and Other Stimulants

Diminished responses and different profiles of proliferative, helper, and cytotoxic T-cell responses are elicited against rotavirus in children compared to adults or other stimulants as shown in Table 4. In a study by Jaimes et al., rotavirus-specific CD4+IFN-γ+Th1, CD4+IL-13+Th2, and CD8+IFN-γ+ cytotoxic T-cells, were investigated in children with rotavirus diarrhea in comparison to recently infected, exposed, and unexposed healthy adults. When compared, rotavirus-exposed adults had significantly higher mean proportions of rotavirus-specific Th1 and cytotoxic responses than children whose responses were similar to those observed in healthy adults. However, while the Th1 and cytotoxic T-cell responses were induced by rotavirus in both adults and children, the Th2 response was additionally observed in children with rotavirus diarrhea at a similar frequency to the Th1 response but not in adults [24]. In contrast, a study by Parra et al. showed a predominance of monofunctional CD4+IFN-γ+ and CD4+TNF-α+ Th1 response in both adults and children [30]. Another study found T-cell proliferative responses to rotavirus were generally weaker in prospectively studied children compared to adults with the adults having significantly stronger T-cell proliferation to both bovine and human rotavirus strains than any age group of children [26]. A study looking at frequencies of CD4+IFN-γ+ or IL-2+Th1, CD4+IL-13+Th2, CD4+IL-17+Th17 and CD8+IFN-γ+ cytotoxic T-cells in children with rotavirus and non-rotavirus diarrhea in comparison with healthy and acutely or convalescent rotavirus infected adults found similar observations. Little to no Th1, Th2, or Th17 rotavirus-specific T-cell responses were observed in children with diarrhea and few responses observed comprised Th1 and cytotoxic responses and were only observed among children with prior exposure to or existing acute rotavirus diarrhea. In contrast to children, a much larger proportion of adults, both healthy and acutely infected had detectable Th1 and cytotoxic T-cell responses [27]. These results are similar to another study that showed secretion of IFN-γ, TNF-α, GM-CSF, RANTES, MCP-1, and IL-10 from rotavirus stimulated cells in adults but not in children [30].

In comparison to other viral and bacterial stimulants, circulating rotavirus-specific T-cell responses are generally diminished. While significantly higher proliferation to rotavirus was observed in adults than children, proliferation in response to mycobacterium purified protein derivative (PPD) in children was as high as that observed in adults [26]. Among healthy children, T-cell proliferation to rotavirus was observed to be generally lower in comparison to proliferation against tetanus toxoid (TT), mycobacterium PPD antigens, and Coxsackie B4 virus (CBV) antigen [25,30]. Significantly lower frequencies of IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-2 producing CD4 T-cells were observed against rotavirus than in response to Influenza virus antigens in children [30]

3.8. Rotavirus Activates Proinflammatory, Regulatory and Gut Homing Effector T-Cell Phenotypes

The T-cell immune response to rotavirus in children is characterized by an elevated activated and proinflammatory T-cell profile (Table 5). Children with rotavirus diarrhea show higher proportions of proinflammatory T-helper 17 cells complemented by higher levels of peripheral blood circulating pro-inflammatory IL-6 and IL-17 cytokines at the time of acute infection compared to healthy children [21]. Similarly, a case report of a child with rotavirus gastroenteritis reported elevated proportions of IFN-γ producing helper and cytotoxic T-cells in the acute phase of infection although these levels were reduced by convalescence [23]. Likewise, another study showed a positive correlation between T-cell proliferative responses to rotavirus and messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) expression of proinflammatory IFN-γ and IL-4 cytokines in healthy children [25]. Similar to these findings, a microarray analysis study of immune cell mRNA gene expression by Wang et al. revealed that children with rotavirus diarrhea had upregulation of genes encoding lymphocyte activation markers, proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and immune proteins in the acute stage compared to healthy children. Interestingly, although there was an elevated gene expression of lymphocyte activation markers CD69 and CD83 as well as genes encoding for the differentiation, maturation, activation, and survival of B lymphocytes, there was a reduced expression of genes involved in the proliferation, differentiation, activation, survival, and homeostasis of T lymphocytes in these rotavirus infected children [34].

Table 5.

T-cell activation, proinflammatory, regulatory and homing phenotypes in response to rotavirus.

The proinflammatory T-cell response to rotavirus may occur in association with either a lowered or elevated regulatory T-cell response (Table 5). Dong et al. found that rotavirus infected children had a significantly lower proportion of regulatory T-cells compared to healthy children. The lower regulatory cell profile corresponded to significantly lower levels of circulating immunosuppressive IL-10 and TGF-β cytokines [21]. In contrast, a study by Mesa et al. showed that a TGF-β dependent regulatory mechanism of rotavirus specific CD4 and CD8 IFN-γ T-cell response was absent in children with acute rotavirus gastroenteritis but present in adults, although only four and three adults were studied respectively, and showed that the lowered circulating frequency of rotavirus specific T-cells was not due to regulation by TGF-β+ regulatory T-cells as both rotavirus-infected and healthy children had similar proportions of these circulating Treg profiles [27]. Furthermore, another study found a positive correlation between T-cell proliferative responses and immunosuppressive IL-10 but supporting the previous studies this was not observed for TGF-β [25]. One other study also found elevated expression of other inflammation-modulating proteins IL-1R antagonist, IFN α/β receptors and IFN-stimulated proteins in rotavirus infected children [34].

Two studies reported that a substantial proportion of rotavirus-experienced T-cells express gut homing markers. As shown in Table 5, one study by Rott et al. among children convalescing after acute rotavirus infection reported higher T-cell proliferative response to rotavirus in the α4β7hi lymphocyte population than α4β7− lymphocyte population although this was based on cellular data obtained from one child [33]. Likewise, another study among rotavirus vaccinated children found that most of the rotavirus antigen-experienced CD4+ T cells expressed α4β7 gut homing marker with most cells expressing both, α4β7 and CCR9, gut homing markers [31].

4. Discussion

We provide an overview of the evidence and characteristics of T-cell immune responses to rotavirus in healthy, rotavirus infected, and vaccinated children. Although many research studies have been done, very few of them specifically address T-cell mediated immunity to rotavirus in children. We found only seventeen articles to include in this review.

4.1. Summary Findings and Implications

The majority of studies identified were within the context of rotavirus infection and only two studies assessed T-cell responses in relation to rotavirus vaccination. This is particularly surprising considering the continued development and introduction of new rotavirus vaccines [6,38] and the fact that immune correlates of protection for rotavirus vaccines remain elusive to date [7]. Additionally, the least number of studies were conducted in African children which is of concern as this region bears the highest burden of rotavirus diarrhea [3] and rotavirus vaccines within this region consistently exhibit diminished performance [17]. These findings highlight the gap in research elucidating the role of T-cell mediated immunity to rotavirus to explore their potential as immune correlates of vaccine protection and the need for a better understanding of rotavirus immune mechanisms. Such research would particularly help understand the reduced vaccine immunogenicity in African children.

T-cell immunity does play a role in the immune response to rotavirus in children. Lymphoproliferative assays provided evidence of circulating rotavirus-specific T-cells in children. The lack of proliferation observed in newborns, minimal proliferation in infants <1-year-old, and increasing proliferation with age are consistent with the exposure pattern to rotavirus in early life. However, the minimal rotavirus-specific T-cell proliferation in children aged below 1 year of age is of concern as rotavirus vaccines are administered within this period and vulnerability to rotavirus is highest in early infancy. While transplacental maternal antibody immunity is most probably important for protection in this age group, it may be necessary for new rotavirus vaccine formulations to incorporate designs allowing for enhanced T-cell activation such as the addition of adjuvants. Interestingly, evidence of rotavirus T-cell proliferation is also seen in some newborns that could be a result of in-utero or very early exposure to rotavirus antigens and is of significance for neonatal rotavirus vaccines strategies. Rotavirus vaccines administered at birth have been developed and found to be safe and highly efficacious in newborns. This birth dose vaccination could potentially impart rotavirus-specific memory T-cells thus providing an opportunity for cell-mediated protection very early on in life [39]. This early protection would have a considerable impact on further reduction of rotavirus burden in low-income countries where a sizeable proportion of children are infected with rotavirus before receipt of the first vaccine dose that has been associated with poor vaccine seroconversion [11,40].

Broadening of cross-reactive T-cells with increasing age is consistent with exposure to different rotavirus strains as children age. These results further implied that rotavirus-specific T-cells recognize epitopes shared by different infecting rotavirus serotypes indicating that T-cell immunity can provide cross-reactive protection. Rotavirus has a large strain diversity based on varying combinations of G- and P-serotypes and genotypes classified by antibody reactivity to VP7 and VP4 viral proteins respectively [8]. Rotavirus strains that cause infections in humans and commonly infect children aged <5 years are well known but evolutionary genetic mutation and reassortments eventually give rise to new strains [41]. This observed T-cell proliferation irrespective of infecting G-serotype suggests that rotavirus induced T-cell immunity in children is not G-serotype specific which is important for effective vaccine strategies. For instance, Rotarix, a monovalent G1P [8] rotavirus vaccine has shown protection against non-vaccine serotype rotavirus strains, however, vaccine strain breakthrough still occurs and the extent to which this cross-reactive immunity is mediated by T-cells or antibody responses is unclear and needs further investigation [42]. Total circulating antibody and homotypic and heterotypic neutralizing antibodies are associated but not entirely correlated with protection, which has suggested that other immune mechanisms like these cross-reactive T-cells are likely at play [7].

The available literature shows that both memory B and T-cell immunity are developed after rotavirus exposure with T-cell responses occurring in tight association with the antibody response. This review revealed more frequently detected T-cell responses in children that were seropositive than those seronegative for rotavirus-specific antibodies as well as in secondary versus primary infections. However, the antibody response is more persistent and due to the more transient nature of the T-cell response, T-cell immunity detected in children most likely reflects previous rather than active exposure. Therefore, in infants, T-cell immunity may be more useful as a measure of child-specific immune memory and in early infancy to discriminate from passively acquired maternal immune memory in response to infection. Additionally, in the context of vaccination, detection within shorter time periods post-vaccination would be required in the assessment of these effector T-cell responses. Nevertheless, the detection of both T-cells and antibody responses is necessary to adequately describe the immune response to rotavirus in children infection.

Evidence of T-cell proliferation in the absence of increasing antibody titers in some children speaks towards the existence of anti-rotavirus protection mediated via a direct T-cell immune effector in children. The direct effector contribution of T-cells has been shown in murine model depletion and adoptive studies where depletion of CD8 T-cells resulted in the delayed rate of resolution of rotavirus infection, CD4 T-cell depletion was associated with chronic viral shedding and complete loss of protection [14], and adoptive transfer of rotavirus primed CD4 and CD8 T-cells resulted in shorter rotavirus shedding [43]. In such murine studies, a significant loss of protection against rotavirus has also been observed in T-cell deficient and T-cell receptor (TCR) knockout mice with the delayed resolution of rotavirus infection attributed to the depletion of the CD4+ T-cell subset, while B-cell and TCR deficient mice remained protected [15]. In this review, direct effects of T-cell immunity were exemplified by the impaired rotavirus antibody response, chronic viral shedding, and inability to clear infection observed in T-cell immunodeficient children. In the context of vaccination, it is plausible that lowered antibody responses detected in non-seroconverting children based on fold change in antibody response may not entirely imply reduced protection as T-cell immunity may provide direct protective and immune memory functions. The contribution of T-cell immune memory in the measurement of vaccine immunogenicity may have implications for measures of vaccine efficacy.

The positive association between higher rotavirus CD4 T-helper cell response and rotavirus seropositivity or higher neutralizing IgG in children highlights the particular importance of indirect protection offered via the CD4 T-cell helper function in the production of the antibody response. In adoptive transfer murine models, rotavirus primed CD4 T-cells and not CD8 T-cells are associated with increased production and maintenance of secretory IgA that is important in mucosal immunity, and both serum IgA and IgG are currently recognized as valuable surrogate endpoints for protection [12]. Therefore, taking this into account, in regions of poor rotavirus vaccine performance, there is a need for elucidating detailed profiles of these CD4 T-cells in relation to the magnitude and neutralizing ability of the antibody responses among vaccinated children. Magnitude and maintenance of antibody response may be reliant on characteristics of the elicited CD4 T-cell response. Such T-cell studies may provide useful insights for the observed lower vaccine immunogenicity and effectiveness trends in these regions.

In children, these characteristics of CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses to rotavirus include predominantly Th1 but also Th17 responses. Activated CD4 and CD8 T-cells secreting proinflammatory cytokines particularly IFN-γ and IL-17 appear important in this immune response. IFN-γ cytokine has direct anti-viral effects and IL-17 is associated with the provision of protection via recruitment of other immune cells with both cytokines shown to be important in the clearance of rotavirus infection [44]. On the other hand, regulatory T-cells which may suppress the proinflammatory immune response in efforts to maintain homeostasis also occur in response to rotavirus. The regulatory T-cells can have a negative or positive influence on the immune response to rotavirus infection or vaccination. This review revealed IL10+ and FOXP3+ regulatory T-cells as distinct subpopulations with opposing effects on rotavirus antibody immunity. In this context, a distinct population of CD4+/CD8a+ CCR6+CXCR6+ Treg cells has been identified in the human colon, which responds to fecal bacterial species and produces IL-10 [45]. These cells could indeed drive distinct outcomes during rotavirus infection compared to their FOXP3+ Treg counterparts. For live attenuated rotavirus vaccines, assessing these Th1 and Th17 inflammatory and FOXP3+ and IL-10+ regulatory T-cell profiles in children may provide insights into the observed vaccine immunogenicity.

In addition to these conventionally studied CD4 and CD8 T-cell subsets, recently identified innate-like T-cells such as the gamma delta T-cell (γδT), mucosal-associated invariant T-cells (MAIT), and natural killer T-cells (NKT) are enriched in mucosal tissues and have been reported to provide protective effector activities against human intestinal infections. Through direct cytokine action or indirectly via recruitment of other immune effector cells cytokine responses, these innate-like T-cells have been suggested to provide early antiviral immune protection in the interface between innate immunity and induction of adaptive immunity and have been associated with inhibited viral replication of important human viral pathogens [46,47]. There is an urgent need to also consider the characterization of these atypical T-cell profiles and how they relate to conventional CD4 and CD8 T-cell subsets in relation to observed rotavirus infection or vaccine immunogenicity.

Circulating rotavirus-specific T-cells in children are generally low in frequency during the acute than convalescent phase and much weaker than those generated in adults and against other pathogens. The lowered frequency of rotavirus-specific T-cells in the initial response may be a direct consequence of their migration from circulation to gut mucosal priming sites to carry out effector function. This is supported by literature documenting higher T-cell proliferation within α4β7hi subset and a higher proportion of CD4 T-cells responding to rotavirus expressing α4β7 or CCR9 gut homing markers. Current live attenuated oral rotavirus vaccines aim to mimic natural infection immune priming within the gut. The extent to which such vaccines elicit these gut homing effector T-cell phenotypes may relate to the protective effect of vaccination. With new parenterally administered rotavirus vaccines being introduced, their ability to elicit these gut homing phenotypes must also be studied. While murine models have documented the development of mucosal immunity from parenteral vaccination [48], the generation of gut homing rotavirus specific T-cells in children vaccinated with parenteral rotavirus vaccine remains to be determined although an observed reduction in viral shedding in clinical trials conducted thus far has implied generation of local mucosal effectors [49]. It will, therefore, be important to conduct studies assessing the homing phenotypes elicited by rotavirus vaccination which may influence effector abilities in the protection against rotavirus at the gut.

When compared to tuberculin, tetanus toxoid, and influenza-derived antigens for which childhood vaccines are also administered, the T-cell responses induced by rotavirus antigen were observed to be diminished. Reasons for such variations in antigen-specific responses in early life can include immune dysfunction in antigen-specific presentation and differences in antigen-specific T-cell activation, proliferation, and effector versus memory generating functions. A better understanding of these T-cell phenotypes responding to rotavirus in this context has the potential to be exploited for improved immunity [50]. Considering the role of T-cell phenotypes in the child’s immune response to infection or vaccinations, it should be important when assessing immune responses in children to account for pathogens that have a strong modulatory effect on these T-cell populations. For instance, cytomegalovirus, a ubiquitous pathogen, and potent T-cell modulator have been shown to influence immune and vaccine-induced T-cell profiles in children [51,52] but data is unavailable on its modulatory effect on anti-rotavirus T-cell immunity in children.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of the T-cell response to rotavirus in children using a clearly defined search and screening strategy to obtain existing literature. Our review gives an overview of research done prior to and post introduction of rotavirus vaccines and provides evidence supporting the need for more research on T-cell mediated immunity in children not only as it relates to infection but also vaccination. This review provides current knowledge in the literature on different subsets and characteristics of T-cells response to rotavirus encompassing general proliferation, specific phenotypes, functional cytokine secretion, and migratory profiles. The review also covered the relationship of T-cell responses to widely studied antibody responses.

Limitations in this review primarily arose from the nature of the studies identified. A substantial proportion of studies, particularly those conducted earlier, reported lymphoproliferative activity as an indication of T-cell immunity. However, caution must be taken in their interpretation as the detected proliferation potentially includes that of innate and B-cells. Lymphoproliferative-based measures, while giving insights to T-cell immunity, do not provide specific T-cell immune data in comparison to current more advanced techniques such as multicolor flow cytometry. Additionally, aside from four studies, the majority were conducted within the last decade and as such did not utilize more recent immunological methods such as higher cell marker parameter flow cytometry to provide more comprehensive T-cell knowledge.

Another limitation is that the studies identified used a diverse range of immune stimulants to assess the rotavirus T-cell responses which included different rotavirus strains or mitogens and had variations in reporting format for the T-cell outputs. This introduced large methodological heterogeneity that presented a major challenge in the quantitative synthesis of the evidence that was provided. Additionally, there was a lack of sufficient reporting of statistical data in several studies and more so in studies conducted much earlier on, and for some studies, sample sizes were very small making generalization of findings difficult.

5. Conclusions

T-cells clearly have a role to play in the immune response to rotavirus in children. This review shows that these responses are heterotypic and although present at low circulating levels and less persistent than antibodies, can be detected in children and develop through repeated exposure. Both CD8 and CD4 T-cell subsets are involved in this response and are primarily of a Th1 and gut homing phenotype. However, there is a paucity of T-cells studies, wide methodological differences, and a lack of sufficient quantitative data sets directly associating T-cell immunity to protection from rotavirus infection or in relation to immunogenicity of rotavirus vaccines. Thus, it is imperative that further research be done investigating T-cell responses against rotavirus and the standardization of rotavirus-specific T-cells assays is needed in this population.

Africa bears a disproportionate burden of rotavirus diarrheal disease and has an urgent need for research in this area. Such studies may also establish whether the observed lower vaccine-induced anti-rotavirus antibodies in African children could be attributed to limited or impaired T-cell responses. There is also a need to address innate-like T-cell subsets and the inclusion of more phenotypic markers using more developed immunological assays to provide comprehensive T-cell immunology data. In rotavirus vaccinology, it will be important to assess T-cell immunity relationship to seroconversion rates and clinical protection against rotavirus infection. Such research could form a good basis for further exploration of T-cells as a potential immune correlate of protection and inform the development of next-generation vaccines.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/v14030459/s1, Table S1: PRISMA checklist, File S1: Search strategy example, Table S2: Quality assessment tool.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.L. and R.C.; methodology, N.M.L., S.B., C.C., M.S. and O.N.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.L.; writing—review and editing, M.R.G., S.B., C.C., M.S., O.N.C. and R.C.; supervision, M.R.G. and R.C.; funding acquisition, N.M.L. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust grant [211356/Z/18/Z] awarded to N.M.L and the EDCTP2 programme supported by the European Union Senior Fellowship grant awarded to R.C (grant number TMA2016SF-1511-ROVAS-2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is included within the article.

Acknowledgments

N.M.L. acknowledges the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIDRZ) and CIDRZ Enteric Disease and Vaccine Research Unit for resources and support rendered in performing the systematic review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kotloff, K.L.; Nataro, J.P.; Blackwelder, W.C.; Nasrin, D.; Farag, T.H.; Panchalingam, S.; Wu, Y.; Sow, S.O.; Sur, D.; Breiman, R.F.; et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): A prospective, case-control study. Lancet 2013, 382, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotloff, K.L.; Nasrin, D.; Blackwelder, W.C.; Wu, Y.; Farag, T.; Panchalingham, S.; Sow, S.O.; Sur, D.; Zaidi, A.K.M.; Faruque, A.S.G.; et al. The incidence, aetiology, and adverse clinical consequences of less severe diarrhoeal episodes among infants and children residing in low-income and middle-income countries: A 12-month case-control study as a follow-on to the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS). Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e568–e584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troeger, C.; Blacker, B.F.; Khalil, I.A.; Rao, P.C.; Cao, S.; Zimsen, S.R.M.; Albertson, S.B.; Stanaway, J.D.; Deshpande, A.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1211–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, E.; Jonesteller, C.L.; Tate, J.E.; Yen, C.; Parashar, U.D. Global Impact of Rotavirus Vaccination on Childhood Hospitalizations and Mortality From Diarrhea. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 1666–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parashar, U.D.; Johnson, H.; Steele, A.D.; Tate, J.E. Health Impact of Rotavirus Vaccination in Developing Countries: Progress and Way Forward. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, S91–S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.M.; Tate, J.E.; Kirkwood, C.D.; Steele, A.D.; Parashar, U.D. Current and new rotavirus vaccines. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 32, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, J.; Steele, A.D.; Franco, M.A. Correlates of protection for rotavirus vaccines: Possible alternative trial endpoints, opportunities, and challenges. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2014, 10, 3659–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desselberger, U. Rotaviruses. Virus Res. 2014, 190, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez, F.R.; Matson, D.O.; Calva, J.J.; Guerrero, M.L.; Morrow, A.L.; Carter-Campbell, S.; Glass, R.I.; Estes, M.K.; Pickering, L.K.; Ruiz-Palacios, G.M. Rotavirus Infection in Infants as Protection against Subsequent Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 335, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desselberger, U.; Huppertz, H.-I. Immune responses to rotavirus infection and vaccination and associated correlates of protection. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 203, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilengi, R.; Simuyandi, M.; Beach, L.; Mwila, K.; Becker-Dreps, S.; Emperador, D.M.; Velasquez, D.E.; Bosomprah, S.; Jiang, B. Association of Maternal Immunity with Rotavirus Vaccine Immunogenicity in Zambian Infants. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.M.; Tate, J.E.; Leon, J.; Haber, M.J.; Pitzer, V.E.; Lopman, B.A. Postvaccination Serum Antirotavirus Immunoglobulin A as a Correlate of Protection Against Rotavirus Gastroenteritis Across Settings. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Carmolli, M.; Dickson, D.M.; Colgate, E.R.; Diehl, S.A.; Uddin, M.I.; Islam, S.; Hossain, M.; Rafique, T.A.; Bhuiyan, T.R.; et al. Rotavirus-Specific Immunoglobulin A Responses Are Impaired and Serve as a Suboptimal Correlate of Protection Among Infants in Bangladesh. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeal, M.M.; Rae, M.N.; Ward, R.L. Evidence that resolution of rotavirus infection in mice is due to both CD4 and CD8 cell-dependent activities. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 8735–8742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeal, M.M.; VanCott, J.L.; Choi, A.H.; Basu, M.; Flint, J.A.; Stone, S.C.; Clements, J.D.; Ward, R.L. CD4 T cells are the only lymphocytes needed to protect mice against rotavirus shedding after intranasal immunization with a chimeric VP6 protein and the adjuvant LT(R192G). J. Virol. 2002, 76, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosé, J.R.; Williams, M.B.; Rott, L.S.; Butcher, E.C.; Greenberg, H.B. Expression of the mucosal homing receptor α4β7 correlates with the ability of CD8+ memory T cells to clear rotavirus infection. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 726–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. Update on rotavirus vaccine underperformance in low- to middle-income countries and next-generation vaccines. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 1787–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The, P.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrotri, M.; van Schalkwyk, M.C.I.; Post, N.; Eddy, D.; Huntley, C.; Leeman, D.; Rigby, S.; Williams, S.V.; Bermingham, W.H.; Kellam, P.; et al. T cell response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimzadeh, M.; Naderi, N. Toward an understanding of regulatory T cells in COVID-19: A systematic review. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 4167–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Qu, S.; Chen, X.; Zhu, H.; Tai, X.; Pan, J. Changes in the cytokine expression of peripheral Treg and Th17 cells in children with rotavirus enteritis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 10, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaraby, I.; Elsharkawy, S.; Abbassy, A.; Hussein, M. A Study on Delayed-Hypersensitivity to Rotavirus in Infancy and Childhood. Ann. Trop. Paediatr. 1992, 12, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasa, T.; Matsubayashi, N. Protein-loosing enteropathy associated with rotavirus infection in an infant. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 1630–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaimes, M.C.; Rojas, O.L.; Gonzalez, A.M.; Cajiao, I.; Charpilienne, A.; Pothier, P.; Kohli, E.; Greenberg, H.B.; Franco, M.A.; Angel, J. Frequencies of virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes secreting gamma interferon after acute natural rotavirus infection in children and adults. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 4741–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makela, M.; Oling, V.; Marttila, J.; Waris, M.; Knip, M.; Simell, O.; Ilonen, J. Rotavirus-specific T cell responses and cytokine mRNA expression in children with diabetes-associated autoantibodies and type 1 diabetes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2006, 145, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makela, M.; Marttila, J.; Simell, O.; Ilonen, J. Rotavirus-specific T-cell responses in young prospectively followed-up children. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2004, 137, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesa, M.C.; Gutierrez, L.; Duarte-Rey, C.; Angel, J.; Franco, M.A. A TGF-beta mediated regulatory mechanism modulates the T cell immune response to rotavirus in adults but not in children. Virology 2010, 399, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offit, P.A.; Hoffenberg, E.J.; Pia, E.S.; Panackal, P.A.; Hill, N.L. Rotavirus-specific helper T cell responses in newborns, infants, children, and adults. J. Infect. Dis. 1992, 165, 1107–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offit, P.A.; Hoffenberg, E.J.; Santos, N.; Gouvea, V. Rotavirus-specific humoral and cellular immune response after primary, symptomatic infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1993, 167, 1436–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra, M.; Herrera, D.; Jacome, M.F.; Mesa, M.C.; Rodriguez, L.-S.; Guzman, C.; Angel, J.; Franco, M.A. Circulating rotavirus-specific T cells have a poor functional profile. Virology 2014, 468, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra, M.; Herrera, D.; Calvo-Calle, J.M.; Stern, L.J.; Parra-Lopez, C.A.; Butcher, E.; Franco, M.; Angel, J. Circulating human rotavirus specific CD4 T cells identified with a class II tetramer express the intestinal homing receptors α4β7 and CCR9. Virology 2014, 452, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, O.L.; Gonzalez, A.M.; Gonzalez, R.; Perez-Schael, I.; Greenberg, H.B.; Franco, M.A.; Angel, J. Human rotavirus specific T cells: Quantification by ELISPOT and expression of homing receptors on CD4+ T cells. Virology 2003, 314, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rott, L.S.; Rose, J.R.; Bass, D.; Williams, M.B.; Greenberg, H.B.; Butcher, E.C. Expression of mucosal homing receptor alpha4beta7 by circulating CD4+ cells with memory for intestinal rotavirus. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 1204–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dennehy Penelope, H.; Keyserling Harry, L.; Tang, K.; Gentsch Jon, R.; Glass Roger, I.; Jiang, B. Rotavirus Infection Alters Peripheral T-Cell Homeostasis in Children with Acute Diarrhea. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 3904–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, A.; Lindsey, J.; Bosch, R.; Persaud, D.; Sato, P.; Ogwu, A.; Asmelash, A.; Bwakura-Dangarambezi, M.; Chi, B.H.; Canniff, J.; et al. B and T cell phenotypic profiles of African HIV-infected and HIV-exposed uninfected infants: Associations with antibody responses to the pentavalent rotavirus vaccine. Front. Immunol. 2018, 8, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J.; David, T.J.; Chrystie, I.L.; Totterdell, B. Chronic enteric virus infection in two T-cell immunodeficient children. J. Med. Virol. 1988, 24, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasukawa, M.; Nakagomi, O.; Kobayashi, Y. Rotavirus induces proliferative response and augments non-specific cytotoxic activity of lymphocytes in humans. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1990, 80, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, C.D.; Ma, L.-F.; Carey, M.E.; Steele, A.D. The rotavirus vaccine development pipeline. Vaccine 2019, 37, 7328–7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bines, J.E.; At Thobari, J.; Satria, C.D.; Handley, A.; Watts, E.; Cowley, D.; Nirwati, H.; Ackland, J.; Standish, J.; Justice, F.; et al. Human Neonatal Rotavirus Vaccine (RV3-BB) to Target Rotavirus from Birth. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, N.; Zaman, K.; Rodrigo, C.; Debrus, S.; Benninghoff, B.; Pemmaraju Venkata, S.; Han, H.-H. Early exposure of infants to natural rotavirus infection: A review of studies with human rotavirus vaccine RIX4414. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentsch, J.R.; Laird, A.R.; Bielfelt, B.; Griffin, D.D.; Bányai, K.; Ramachandran, M.; Jain, V.; Cunliffe, N.A.; Nakagomi, O.; Kirkwood, C.D.; et al. Serotype Diversity and Reassortment between Human and Animal Rotavirus Strains: Implications for Rotavirus Vaccine Programs. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 192, S146–S159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, A.D.; Neuzil, K.M.; Cunliffe, N.A.; Madhi, S.A.; Bos, P.; Ngwira, B.; Witte, D.; Todd, S.; Louw, C.; Kirsten, M.; et al. Human rotavirus vaccine Rotarix™ provides protection against diverse circulating rotavirus strains in African infants: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Lan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Li, Y.; Guo, T. Evaluation of oral Lanzhou lamb rotavirus vaccine via passive transfusion with CD4+/CD8+ T lymphocytes. Virus Res. 2016, 217, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiley, K.L.; McNeal, M.M.; Basu, M.; Choi, A.H.; Clements, J.D.; Ward, R.L. Association of gamma interferon and interleukin-17 production in intestinal CD4+ T cells with protection against rotavirus shedding in mice intranasally immunized with VP6 and the adjuvant LT(R192G). J. Virol. 2007, 81, 3740–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godefroy, E.; Alameddine, J.; Montassier, E.; Mathé, J.; Desfrançois-Noël, J.; Marec, N.; Bossard, C.; Jarry, A.; Bridonneau, C.; Le Roy, A.; et al. Expression of CCR6 and CXCR6 by Gut-Derived CD4+/CD8α+ T-Regulatory Cells, Which Are Decreased in Blood Samples From Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.M.; Round, L.J.; Leung, T.D. Innate-like lymphocytes in intestinal infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 28, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hildreth, A.D.; O’sullivan, T.E. Tissue-resident innate and innate-like lymphocyte responses to viral infection. Viruses 2019, 11, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resch, T.K.; Wang, Y.; Moon, S.-S.; Joyce, J.; Li, S.; Prausnitz, M.; Jiang, B. Inactivated rotavirus vaccine by parenteral administration induces mucosal immunity in mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groome, M.J.; Koen, A.; Fix, A.; Page, N.; Jose, L.; Madhi, S.A.; McNeal, M.; Dally, L.; Cho, I.; Power, M.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a parenteral P2-VP8-P[8] subunit rotavirus vaccine in toddlers and infants in South Africa: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichichero, M.E. Challenges in vaccination of neonates, infants and young children. Vaccine 2014, 32, 3886–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.; Adetifa, J.U.; Noho-Konteh, F.; Njie-Jobe, J.; Sanyang, L.C.; Drammeh, A.; Plebanski, M.; Whittle, H.C.; Rowland-Jones, S.L.; Robertson, I.; et al. Limited Impact of Human Cytomegalovirus Infection in African Infants on Vaccine-Specific Responses Following Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis and Measles Vaccination. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, D.J.; van der Sande, M.; Jeffries, D.; Kaye, S.; Ismaili, J.; Ojuola, O.; Sanneh, M.; Touray, E.S.; Waight, P.; Rowland-Jones, S.; et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in Gambian infants leads to profound CD8 T-cell differentiation. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 5766–5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).