Abstract

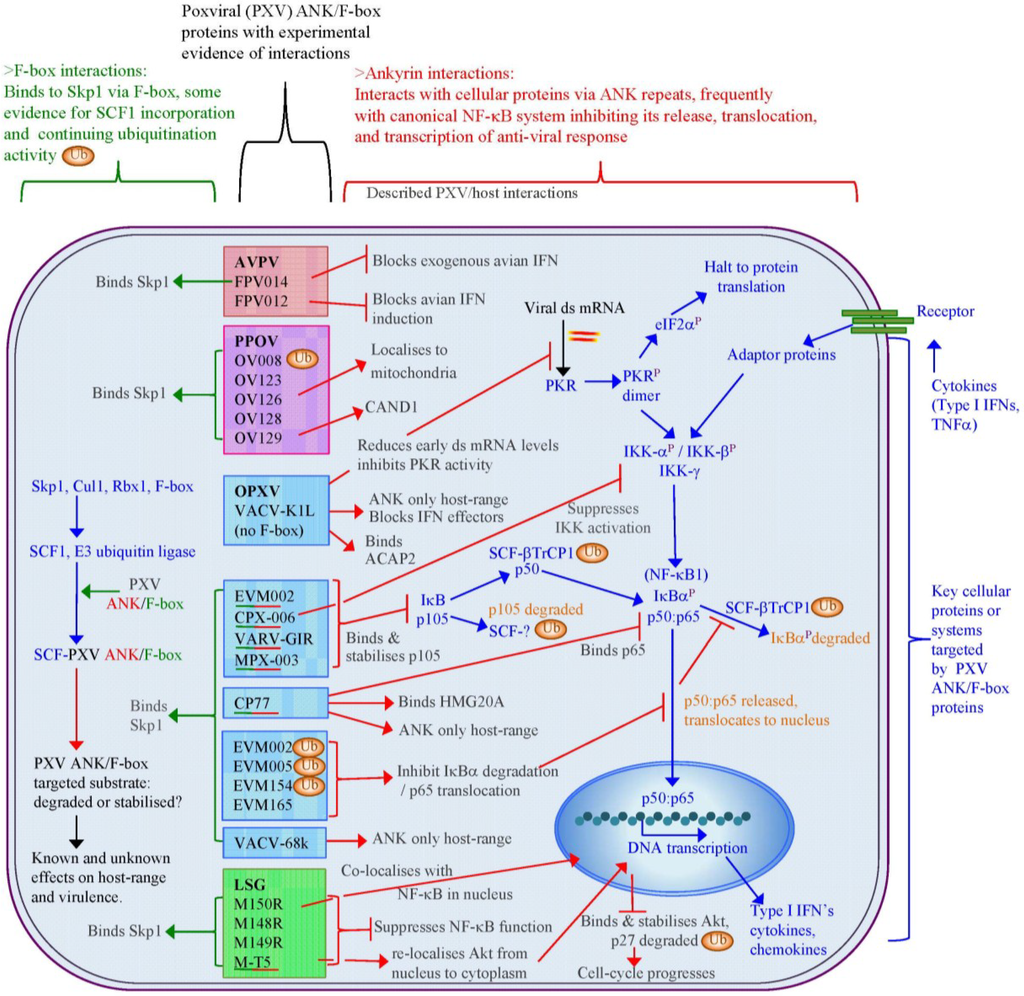

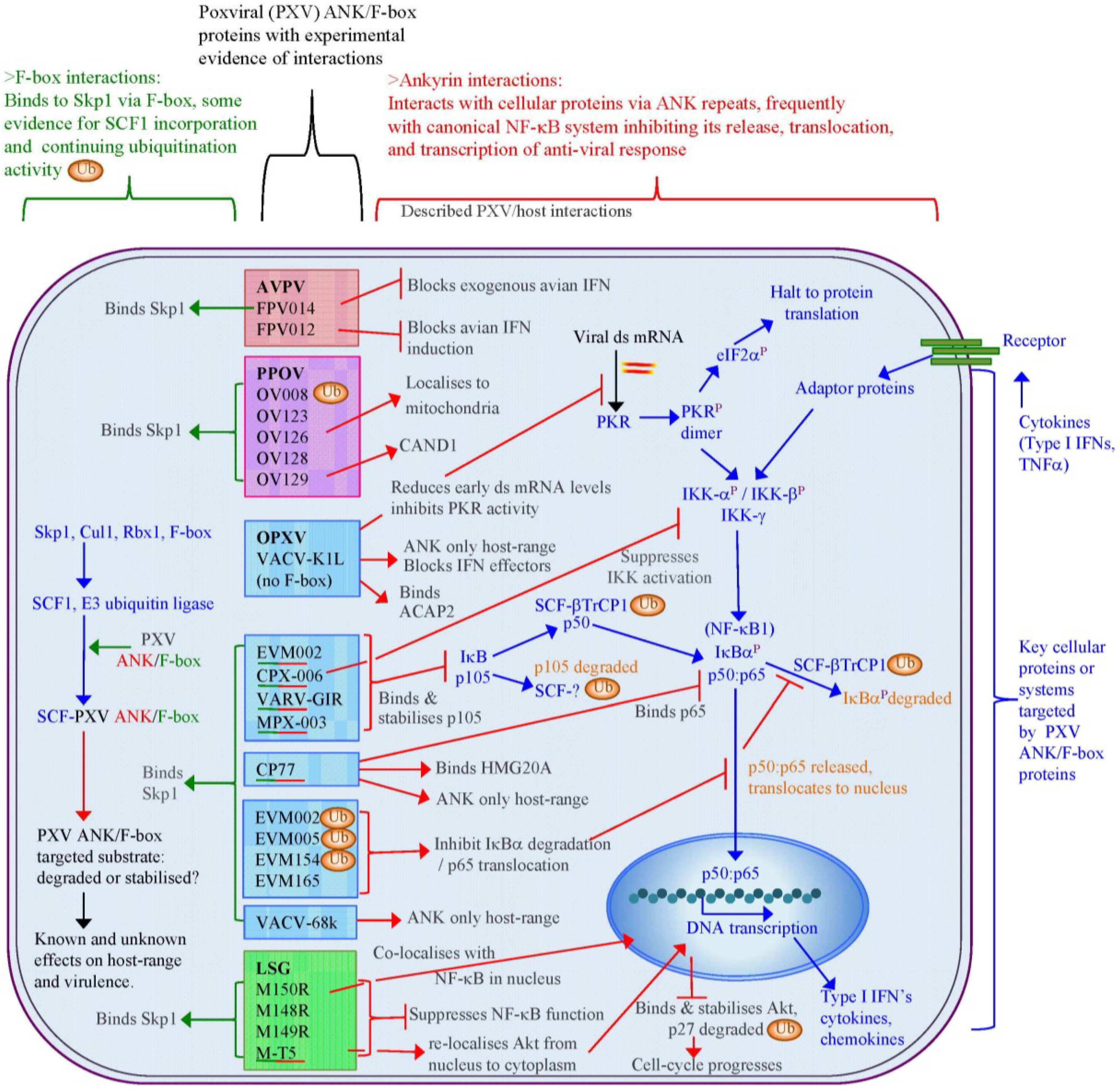

Multiple repeats of the ankyrin motif (ANK) are ubiquitous throughout the kingdoms of life but are absent from most viruses. The main exception to this is the poxvirus family, and specifically the chordopoxviruses, with ANK repeat proteins present in all but three species from separate genera. The poxviral ANK repeat proteins belong to distinct orthologue groups spread over different species, and align well with the phylogeny of their genera. This distribution throughout the chordopoxviruses indicates these proteins were present in an ancestral vertebrate poxvirus, and have since undergone numerous duplication events. Most poxviral ANK repeat proteins contain an unusual topology of multiple ANK motifs starting at the N-terminus with a C-terminal poxviral homologue of the cellular F-box enabling interaction with the cellular SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. The subtle variations between ANK repeat proteins of individual poxviruses suggest an array of different substrates may be bound by these protein-protein interaction domains and, via the F-box, potentially directed to cellular ubiquitination pathways and possible degradation. Known interaction partners of several of these proteins indicate that the NF-κB coordinated anti-viral response is a key target, whilst some poxviral ANK repeat domains also have an F-box independent affect on viral host-range.

1. Poxviruses

Poxviruses are nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses (NCLDV) [1,2] that replicate exclusively in the cytoplasm and maintain genomes of 130 to >350 kilobases. They infect a wide range of vertebrate and invertebrate hosts and are divided into two sub-families: the Chordopoxvirinae, which infects vertebrate hosts (reptiles, mammals and birds), and the Entomopoxvirinae, which infect invertebrates (insects) [3]. The chordopoxviruses consist of 10 classified genera and contains the most well-known and well-studied species, including the infamous causative agent of smallpox, variola virus, as well as the non-virulent vaccinia virus that enabled the global eradication of smallpox by vaccination [4,5]. Poxviral infections can exert significant burdens in livestock and wild animal populations and can produce dramatic effects in new host species. This is most vividly shown by the myxoma poxvirus, which produces the fatal disease of myxomatosis in European rabbits but not in its natural host species, American rabbits [6]. Several poxviruses are zoonotic but have a limited impact on human health with low virulence, the main exception being the historical influence of smallpox with its high morbidity and mortality. Contemporary infections of humans by poxviruses are generally limited in immunocompetent individuals, although the monkeypox virus does have a low mortality rate in zoonotic infections [7,8,9].

The genomic content and organisation is highly similar across poxviruses, and especially within the chordopoxviruses. Genes required for poxviral DNA replication and transcription, along with those involved in virion morphogenesis and structure are typically located within a highly conserved central region of the poxviral genome. Comparative analysis of published poxviral genomes demonstrates that 90 genes are conserved in all poxviral species, of which approximately 40 are conserved only in the chordopoxviruses [10,11,12]. There is also a well-conserved synteny between these genes in most chordopoxviruses, but this is reduced in the avipoxviruses, and does not extend to the entomopoxviruses [13]. Although the protein similarity within genera appears sufficient for effective vaccination by cross-protection between species [14,15], this does not seem to apply between genera [16]. The terminal regions of the linear poxviral genome introduce a significant variation between poxviral species and are replete with a wide range of genus- or species-specific genes. Proteins expressed from these terminal regions frequently determine host-range and also significantly contribute to infection and virulence by successfully interfering with the cellular and immune response to viral presence [17,18,19,20].

Located among the terminal regions of the majority of chordopoxviral genomes are genes coding for multiple proteins rich in ankyrin repeats (ANK), 33 residue-repeating motifs commonly associated with protein-protein binding. ANK repeat proteins are highly abundant in the Avipoxvirus genus, with 26 ANK repeat proteins detected in a pigeonpox virus (FeP2 strain), 31 present in fowlpox virus (Iowa strain), and 51 found in canarypox virus (ATCC VR111 strain) [21,22,23]. ANK repeat proteins become less prevalent within the Orthopoxvirus genus ranging from ten within variola virus (Bangladesh 1975 strain) to 15 within cowpox virus (Brighton Red strain) [17,24,25,26,27,28]. ANK repeat proteins are less numerous again within the Capripoxvirus, Leporipoxvirus, Suipoxvirus, Yatapoxvirus and Cervidpoxvirus genera [29,30,31,32,33] referred to as the Leporipoxvirus super-group (LSG) [34], or alternatively as clade II genera (based on their clustering separately from the clade I orthopoxviruses) [35]; a similar number are also present within genomes of the Parapoxvirus genus [36,37,38], and the unclassified cotia virus species [39]. ANK repeat proteins are absent from the known species of Molluscipoxvirus, Crocodylidpoxvirus and the red squirrel poxvirus [34,40,41,42,43] and from all the known Entomopoxvirus genera [44,45,46].

2. The Ankyrin Repeat Motif

The ANK repeat motif is known to be one of the most abundant in nature [47]. The Pfam database contains 134027 sequences representing 3000 species within the ANK repeat super-family (Table 1). The majority of these predicted ANK repeat proteins are found in eukaryotic species, whilst bacterial representatives are not as common, and even fewer are found in archaeal species; viral ANK repeat proteins are mainly, but not exclusively, limited to the poxviruses [48]. Furthermore, the range of different sequences of ANK repeat proteins is greater throughout the eukaryotes, with less variation seen within the other kingdoms.

Table 1.

Pfam ankyrin groups. The ankyrin repeat superfamily (Pfam clan CLO465) contains several groups of ANK repeat proteins. Species and sequence distribution, along with numbered of determined crystal structures, amongst the groups for all species, and for poxvirus species only.

| Pfam Ankyrin Group | Pfam Identifier | All Species | Poxvirus Only | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Sequences | Structures | Species | Sequences | Structures | ||

| ANK1 | PF00023 | 897 | 8812 | 214 | 42 | 247 | 0 |

| ANK2 | PF12796 | 2889 | 110723 | 200 | 45 | 478 | 1 |

| ANK3 | PF13606 | 202 | 446 | 0 | 8 | 12 | 0 |

| ANK4 | PF13637 | 729 | 7425 | 31 | 18 | 56 | 0 |

| ANK5 | PF13857 | 768 | 5157 | 6 | 12 | 43 | 0 |

| ANK6 | PF11900 | 51 | 221 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ANK7 | PF11929 | 1 | 1243 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The initial identification of the ANK repeat unit and the first indications of its widespread occurrence came when it was described as a two-repeat motif found within the yeast cell cycle control proteins Sw16 and Cdc10 [49], which also showed consensus to a motif within the Notch protein of Drosophila melanogaster that has five such repeats. This motif was later discovered in, and named after, the human erythrocytic ankyrinR protein [50] that contains 24 repeats of the motif. AnkyrinR links membrane-associated proteins, including ion channels and transporters, and cell adhesion molecules, via its ANK repeat motifs to the cell’s spectrin cytoskeleton scaffold using a spectrin binding domain [51,52,53]. The canonical ankyrinR protein family is not found outside of metazoan organisms, and is believed to have evolved prior to the separation of arthropod and vertebrate lineages, forming an essential component of the support structure for the eukaryotic cell membrane [54,55]. Consensus searches using the ankyrinR protein identified the first ANK repeat units within vaccinia and cowpox viral proteomes [50], with the initial characterisation of ANK repeat protein distribution within poxviral genomes following shortly thereafter with the publication of the vaccinia and variola major virus genomes [26,27,28].

The ANK motif structure comprises two short α-helices connected by β-turns and short loops, and often forms a series of repeats where the β-turn/loop regions align and project away from the α-helices at 90° (Figure 1). This configuration, together with one α-helix (the inner helix) being slightly shorter than the other (the outer helix), produces a distinctive curved structure with a defined outer convex surface and an inner concave surface that is cupped by the β-turn/loops and inner α-helices. The ANK repeats may also be slightly rotated with respect to each other, so in the ankyrinR structure (PDB: 1N11) there is a 2°–3° turn per repeat, contributing to the super-helical form, a complete turn of which would need 32 repeats [47,52].

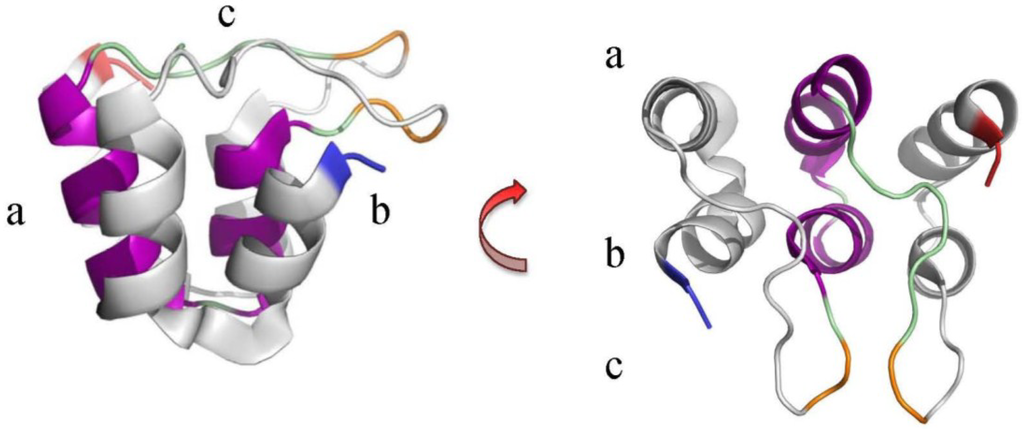

Figure 1.

The ANK repeat unit from the ankyrinR protein. Example of an ANK motif highlighting the 5th repeat unit in the ankyrinR structure (PDB ID: 1N11) [52]. β-turns (orange) within the loops (green) link the helix pairs and project outwards in a conserved manner at an angle of approximately 90° from the α-helices (purple) [47,52,56]. This arrangement has been likened to a “cupped hand” where the convex surface forms the “back” (a)’ the concave surface the “palm” (b)’ and the loops form the “fingers” (c). Blue and red indicate the N- and C-termini respectively.

Figure 1.

The ANK repeat unit from the ankyrinR protein. Example of an ANK motif highlighting the 5th repeat unit in the ankyrinR structure (PDB ID: 1N11) [52]. β-turns (orange) within the loops (green) link the helix pairs and project outwards in a conserved manner at an angle of approximately 90° from the α-helices (purple) [47,52,56]. This arrangement has been likened to a “cupped hand” where the convex surface forms the “back” (a)’ the concave surface the “palm” (b)’ and the loops form the “fingers” (c). Blue and red indicate the N- and C-termini respectively.

Functional analysis has confirmed that the ANK repeat has a structural or regulatory role, rather than an enzymatic one, though it may often be found associated as part of multi-domain proteins, or as part of a multi-protein complex [47,52,57]. The ability to bind proteins is not restricted to a conserved sequence within the consensus ankyrin repeat, but rather it is due to the orientation of the repeat units creating accessible binding sites. These are derived from the arrangement of residues separated in sequence position being brought together to create larger binding patches on the concave or convex surface of the ankyrin protein molecule [57,58]. Examples of structural, and biophysical, characterisation of poxviral ANK repeat proteins are unfortunately scarce, with only the crystal structure of vaccinia virus K1L protein (PDB ID: 3KEA) [58] confirming the presence of the sequence-predicted poxviral ANK motif repeats, and demonstrating the characteristic extended helical form of an ANK repeat protein due to the stacking of the multiple motifs (Figure 2). This structure revealed several unexpected features for this protein with the critical residues known to affect host-range function exposed on the convex surface “back” of the stacked repeats, rather than the concave “palm” usually associated with ANK mediated interactions [47,58]; the authors suggest this may indicate a more transient interaction with host-proteins. There is also an interesting shift in the position of the β-turn loops of approximately 90° after the A4 motif, and, additionally, the entire sequence is composed of ANK repeats, including only partial versions of the ANK motifs at the N- and C-termini [58].

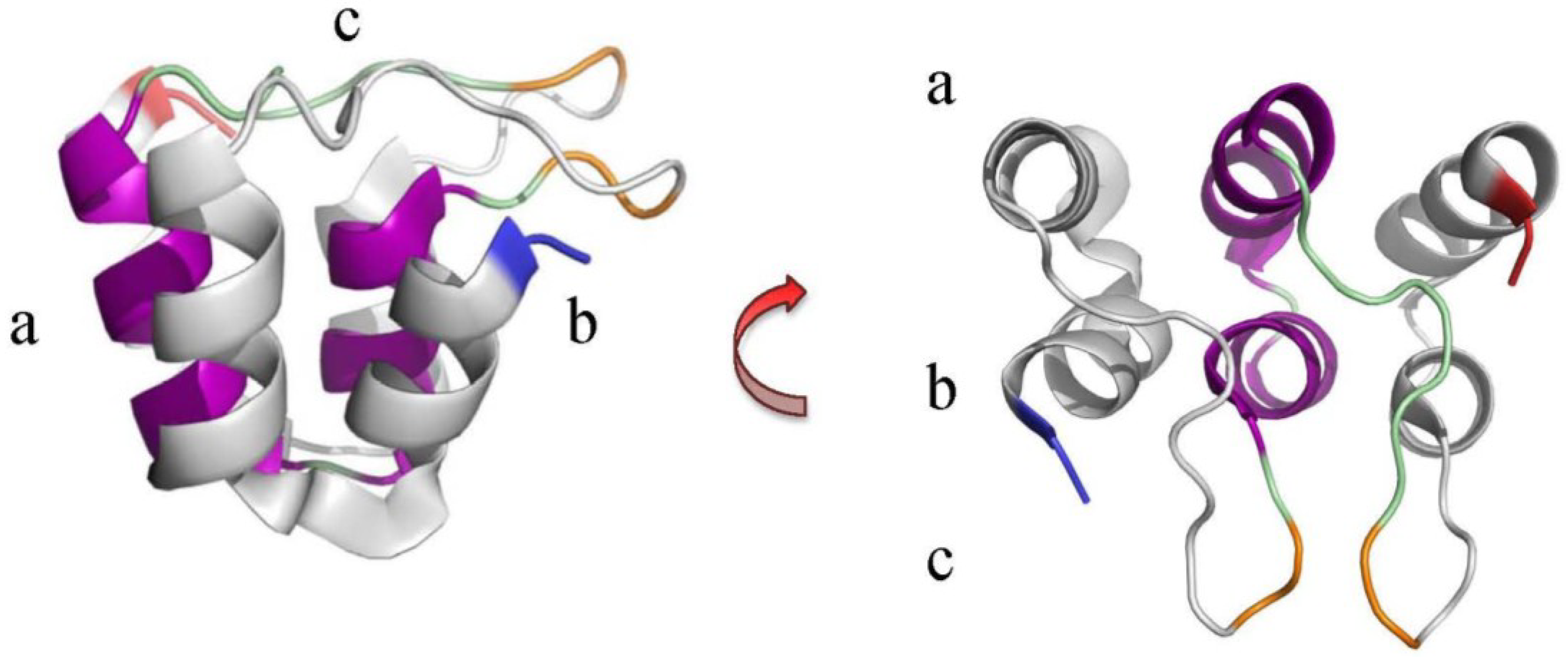

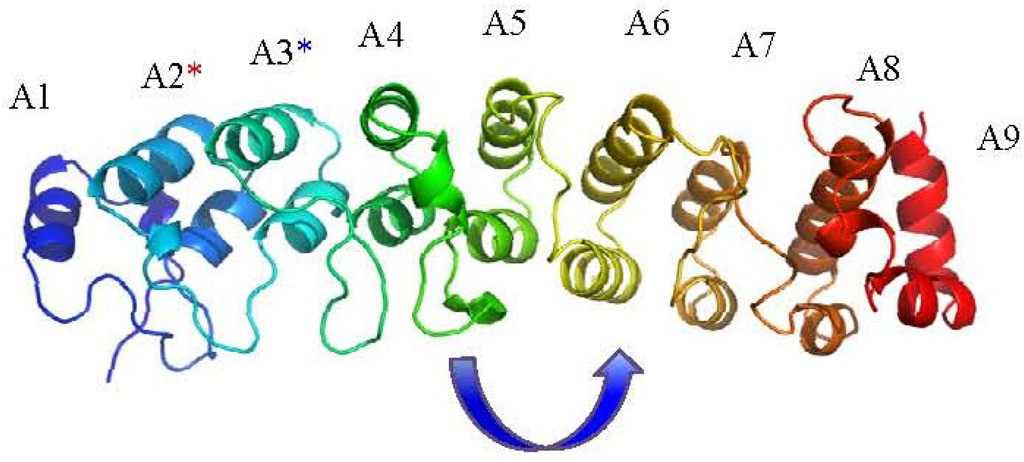

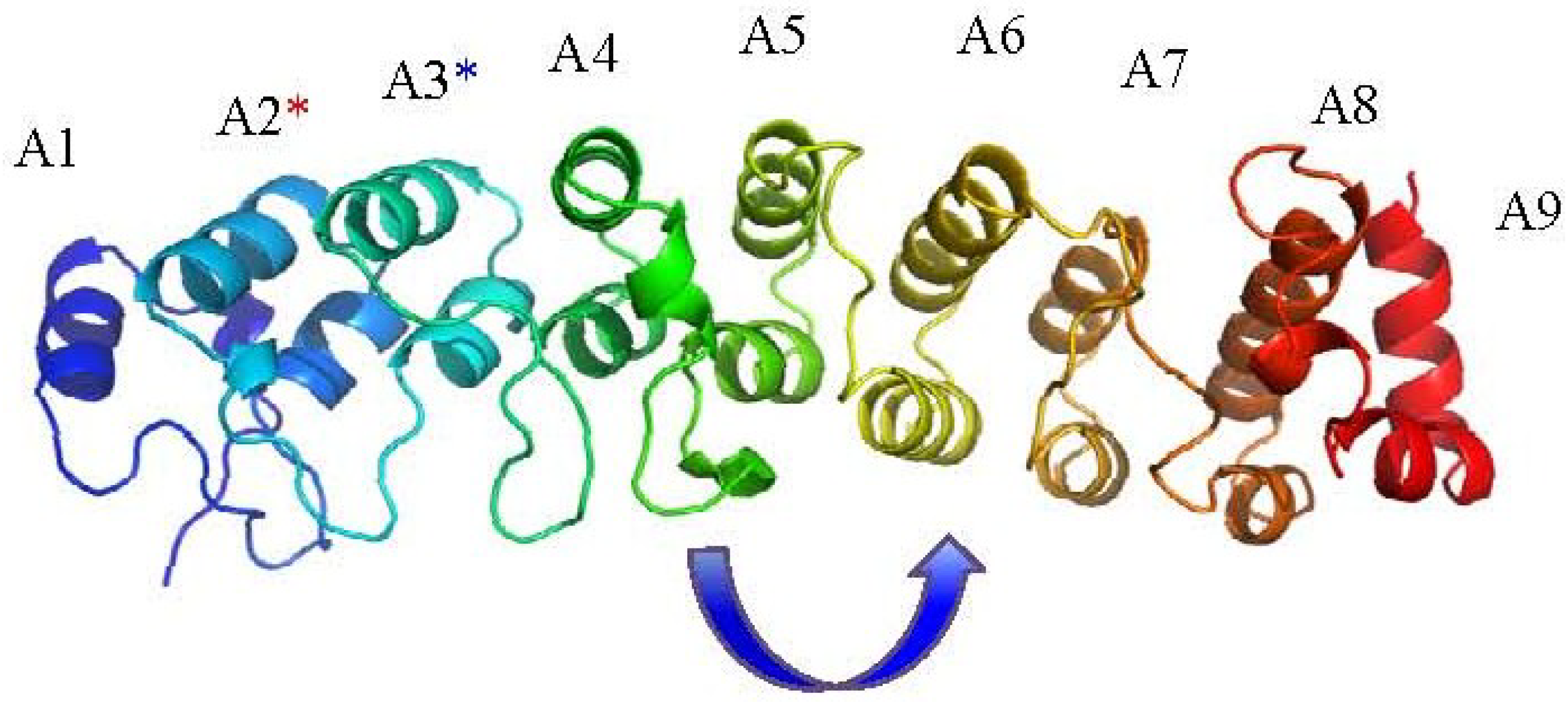

Figure 2.

The vaccinia virus K1L ankyrin protein structure (PDB ID: 3KEA) [58]. ANK repeats are numbered A1-A9; the terminal ANK repeat motifs 1 and 9 are in-complete motifs in the structure. The blue asterisk refers to residues F82 and S83 on A3 [59] required for in vitro viral replication; the red asterisk refers to residues C47 and N51 on the A2 repeat that are spatially contiguous with F82 and S83 and are also required for host-range function. The arrow indicates a surprising 90° shift in the orientation of β-turn loop arrangement from repeats A4 to A5.

Figure 2.

The vaccinia virus K1L ankyrin protein structure (PDB ID: 3KEA) [58]. ANK repeats are numbered A1-A9; the terminal ANK repeat motifs 1 and 9 are in-complete motifs in the structure. The blue asterisk refers to residues F82 and S83 on A3 [59] required for in vitro viral replication; the red asterisk refers to residues C47 and N51 on the A2 repeat that are spatially contiguous with F82 and S83 and are also required for host-range function. The arrow indicates a surprising 90° shift in the orientation of β-turn loop arrangement from repeats A4 to A5.

3. Ankyrin Proteins in Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes

In eukaryotes the ANK motif is thus found associated with many aspects of protein-protein interaction, demonstrating an essential role in eukaryotic cells connecting many regulatory and structural functions [47,56]. Examples of these include scaffolding interactions with the multi-domain ankyrin group, and also the SHANK proteins that contribute to post-synaptic density in neurons, [60,61]. Ankyrin motifs are also associated with proteins involved in intra-cellular signalling, such as the IκB protein, the ANK repeats of which sequester nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) to regulate gene transcription [62,63], the intra-cellular domain of the Notch receptor, which is essential in signalling of transcriptional regulation of cell-cycle processes [64] and the gankyrin oncoprotein, which is composed entirely from seven ANK repeat motifs and that has multiple binding partners related to cell-cycle control [65] Additional multi-domain eukaryotic proteins include the tankyrase 1 and 2 proteins, that contain 22 ANK repeats along with a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase domain and are involved in telomere protection and replication [66] the KANK proteins involved in regulating actin polymerisation [67] the MARP proteins associated with signalling and transcription regulation in muscles [68] and the ANK repeat containing transient receptor protein (TRP) channels involved in sensory signal transduction [69].

With such a multitude of roles ANK repeat proteins have been estimated to comprise ~0.8% of eukaryotic proteomes. An average of 125 ANK repeat proteins are found in any given eukaryotic proteome, but are more prevalent than in bacteria, where they represent approximately 0.1% of the proteome; ANK repeats are even rarer in archaea, at ~0.07% prevalence [48]. However, ANK repeat proteins are enriched in intracellular bacteria that have an obligate or facultative symbiosis with the host, and can constitute to up to 4% of the proteome. Bacterial ANK repeat proteins are found in several intracellular pathogens including Anaplasma phagocytophilum (anaplasmosis in sheep, cattle and humans), Ehrlichia chaffeensis (human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis), Orientia tsutsugamushi (scrub typhus), Legionella pneumophila (Legionnaire’s disease), Coxiella burnetii (Q fever), as well as the obligate endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis [70]. ANK repeat proteins are surprisingly more abundant in poxviruses and can range in prevalence from 2% in parapoxviruses and the LSG group proteomes, to up to 8% in some orthopoxvirus species, and even higher in the avipoxvirus species representing 12% of the fowlpox virus and 15% of canarypox virus proteomes.

9. Conclusions

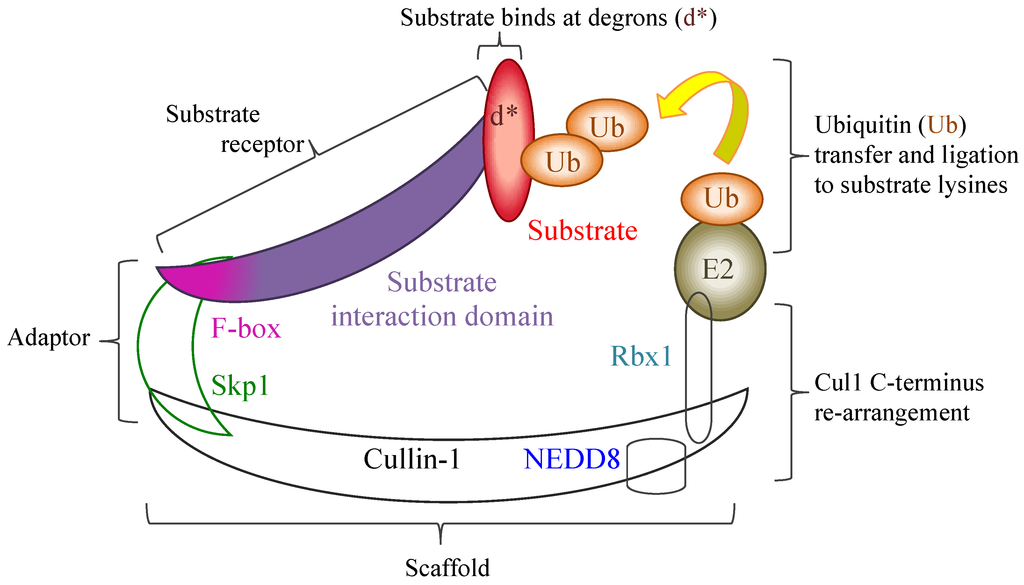

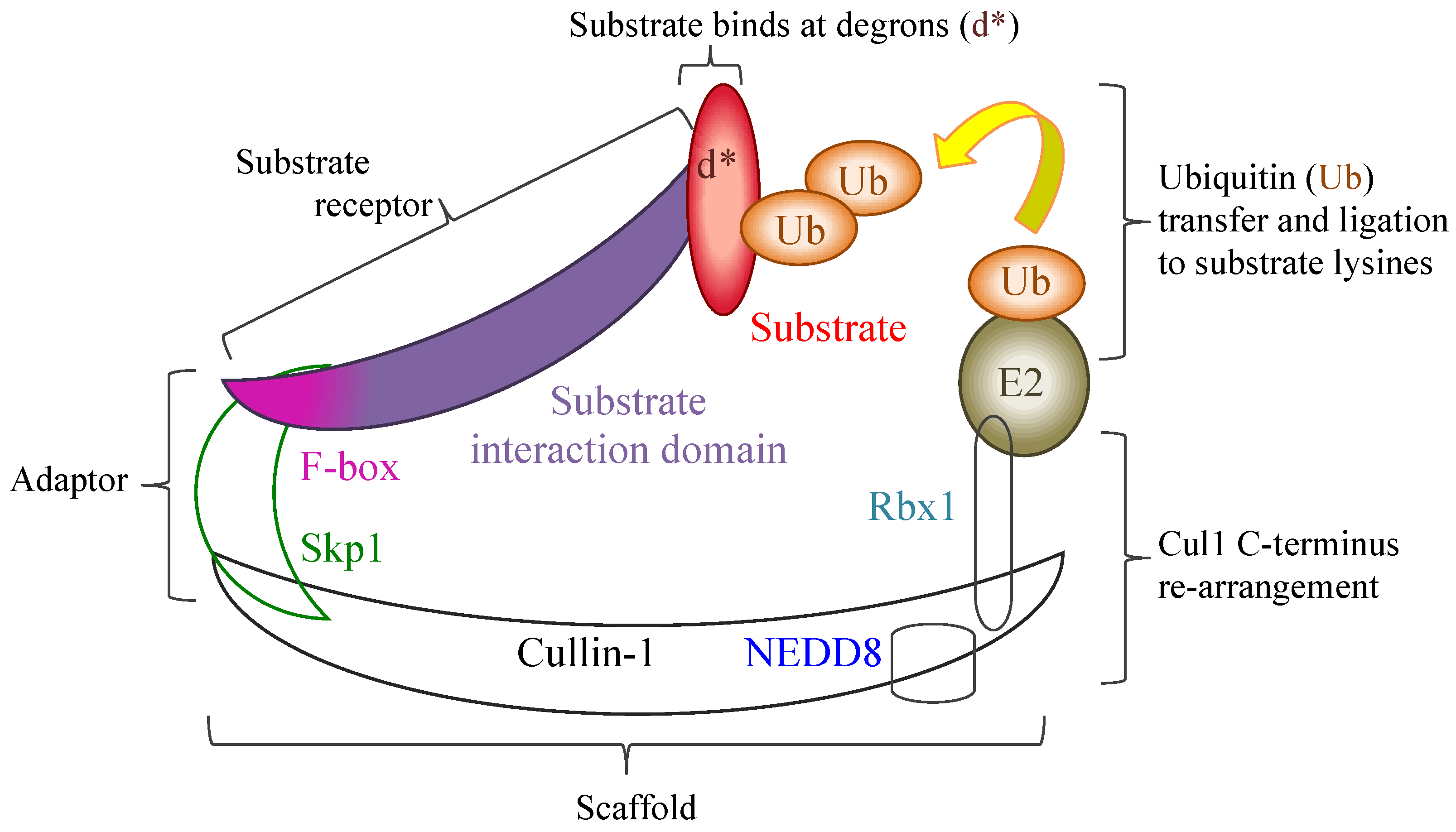

The poxviral ANK/F-box proteins demonstrate a number of conserved features that indicate a shared evolutionary background and role. Poxviral genomes that encode ANK repeat proteins demonstrate a maintenance of a minimal number of ankyrin proteins localised to the terminal regions of the genome, a frequently conserved synteny of these genes between genera, and a segregation into distinct orthologue groups due to gene duplication within and between genera. With the exception of one of these orthologue groups, that contain the ANK repeat K1L protein, all intact proteins have a consistent arrangement of an N-terminal ANK repeat domain and a C-terminal F-box, which have sequence and functional similarity to cellular F-box domains. The majority of poxviruses thus have the potential to interact with the SCF1 ubiquitin ligase complex through a variety of substrate receptors.

Regulation of the SCF1 complex is finely controlled by a variety of proteins and additional complexes that act to block substrate binding, deubiquitinate the complex, and exchange the substrate receptors to re-target the complex. The poxviral ANK repeat proteins must therefore compete within this dynamic and tightly regulated interplay to ensure their effective engagement with the SCF1 complex. While the outcome of this might be expected to be a re-focusing of the infected cell’s degradative capability to the poxviral targets, examples so far have indicated that targeted host proteins, which can act as control points in the anti-viral response (e.g., Akt in the cell-cycle and p105 in NF-κB regulation), are stabilised and protected from the degradation by cellular activity induced by viral infection, thereby maintaining the infected cell in a state conducive to viral replication. The maintenance of a variety of ANK/F-box proteins, often with a redundancy in their effects, within most poxviral species demonstrates the importance of these proteins in viral infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the Squire and Mercer laboratories for helpful discussions. A.A.M. is supported by funding from the Health Research Council of New Zealand and the University of Otago. C.J.S. and M.H.H. were supported by funding from the New Economy Research Fund, and the University of Auckland.

Author Contributions

M.H.H., C.J.S. and A.A.M. conceived the review topic, M.H.H. drafted the manuscript and generated the figures. C.J.S. and A.A.M. corrected and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Iyer, L.M.; Aravind, L.; Koonin, E.V. Common origin of four diverse families of large eukaryotic DNA viruses. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 11720–11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, L.M.; Balaji, S.; Koonin, E.V.; Aravind, L. Evolutionary genomics of nucleo-cytoplasmic large DNA viruses. Virus Res. 2006, 117, 156–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, B. Poxviridae. In Fields Virology; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P.M., Eds.; Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 2129–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.L.; McFadden, G. Smallpox: Anything to declare? Nat. Rev. Immun. 2002, 2, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, D.A. The eradication of smallpox—An overview of the past, present, and future. Vaccine 2011, 295, D7–D9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiesschaert, B.; McFadden, G.; Hermans, K.; Nauwynck, H.; van de Walle, G.R. The current status and future directions of myxoma virus, a master in immune evasion. Vet. Res. 2011, 42, e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damon, I.K. Status of human monkeypox: Clinical disease, epidemiology and research. Vaccine 2011, 295, D54–D59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essbauer, S.; Pfeffer, M.; Meyer, H. Zoonotic poxviruses. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 140, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis-Jones, S. Zoonotic poxvirus infections in humans. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 17, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubser, C.; Hué, S.; Kellam, P.; Smith, G.L. Poxvirus genomes: A phylogenetic analysis. J. Gen. Virol. 2004, 85, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, E.J.; Wang, C.; Upton, C. Poxviruses: Past, present and future. Virus Res. 2006, 117, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upton, C.; Slack, S.; Hunter, A.L.; Ehlers, A.; Roper, R.L. Poxvirus orthologous clusters: Toward defining the minimum essential poxvirus genome. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 7590–7600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratke, K.A.; McLysaght, A. Identification of multiple independent horizontal gene transfers into poxviruses using a comparative genomics approach. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008, 8, e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabenow, J.; Buller, M.; Schriewer, J.; West, C.; Sagartz, J.E.; Parker, S. A mouse model of lethal infection for evaluating prophylactics and therapeutics against monkeypox virus. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 3909–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, H.J.; Alley, M.; Howe, L.; Gartrell, B. Evaluation of the pathogenicity of avipoxvirus strains isolated from wild birds in New Zealand and the efficacy of a fowlpox vaccine in passerines. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 165, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, A.A.; Yirrell, D.L.; Reid, H.W.; Robinson, A.J. Lack of cross-protection between vaccinia virus and orf virus in hysterectomy-procured, barrier-maintained lambs. Vet. Microbiol. 1994, 41, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzhanova, D.; Früh, K. Modulation of the host immune response by cowpox virus. Microbes Infect. 2010, 12, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, J.W.; Cao, J.-X.; Hota-Mitchell, S.; McFadden, G. Immunomodulatory proteins of myxoma virus. Semin. Immun. 2001, 13, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, S.L.; Peng, C.; McFadden, G.; Rothenburg, S. Poxviruses and the evolution of host range and virulence. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 21, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haig, D.M. Orf virus infection and host immunity. Curr. Opin. Immun. 2006, 19, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Afonso, C.L.; Tulman, E.R.; Lu, Z.; Zsak, L.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. The genome of fowlpox virus. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 3815–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offerman, K.; Carulei, O.; van der Walt, A.P.; Douglass, N.; Williamson, A.-L. The complete genome sequences of poxviruses isolated from a penguin and a pigeon in South Africa and comparison to other sequenced avipoxviruses. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, e463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulman, E.R.; Afonso, C.L.; Lu, Z.; Zsak, L.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. The genome of canarypox virus. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, C.L.; Tulman, E.R.; Lu, Z.; Zsak, L.; Sandybaev, N.T.; Kerembekova, U.Z.; Zaitsev, V.L.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. The genome of camelpox virus. Virology 2002, 295, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Danila, M.I.; Feng, Z.; Buller, R.M.L.; Wang, C.; Han, X.; Lefkowitz, E.J.; Upton, C. The genomic sequence of ectromelia virus, the causative agent of mousepox. Virology 2003, 317, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goebel, S.J.; Johnson, G.P.; Perkus, M.E.; Davis, S.W.; Winslow, J.P.; Paoletti, E. The complete DNA sequence of vaccinia virus. Virology 1990, 179, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massung, R.F.; Liu, L.-I.; Knight, J.C.; Yuran, T.E.; Kerlavage, A.R.; Parsons, J.M.; Venter, J.C.; Esposito, J.J. Analysis of the complete sequence of smallpox variola major strain Bangladesh 1975. Virology 1994, 201, 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shchelkunov, S.N.; Blinov, V.M.; Sandakhchiev, L.S. Ankyrin-like proteins of variola and vaccinia viruses. FEBS Lett. 1993, 319, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, C.L.; Tulman, E.R.; Lu, Z.; Zsak, L.; Osorio, F.A.; Balinsky, C.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. The genome of swinepox virus. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, C.L.; Delhon, D.; Tulman, E.R.; Lu, Z.; Zsak, A.; Becerra, V.M.; Zsak, L.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. The genome of deerpox virus. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 966–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, C.; Hota-Mitchell, S.; Chen, L.; Barrett, J.; Cao, J.-X.; Macaulay, C.; Willer, D.; Evans, D.; McFadden, G. The complete DNA sequence of myxoma virus. Virology 1999, 264, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-J.; Essani, K.; Smith, G.L. The genome sequence of yaba-like disease virus, a yatapoxvirus. Virology 2001, 281, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulman, E.R.; Afonso, C.L.; Lu, Z.; Zsak, L.; Sur, J.-H.; Sandybaev, N.T.; Kerembekova, U.Z.; Zaitsev, V.L.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. The genomes of sheeppox and goatpox viruses. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 6054–6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnberg, S.; Fleming, S.B.; Mercer, A.A. Phylogenetic analysis of the large family of poxvirus ankyrin-repeat proteins reveals orthologue groups within and across chordopoxvirus genera. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 2596–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, A.L.; Friedman, R. Poxvirus genome evolution by gene gain and loss. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2005, 35, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhon, G.; Tulman, E.R.; Afonso, C.L.; Lu, Z.; de la Concha-Bermejillo, A.; Lehmkuhl, H.D.; Piccone, M.E.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. Genomes of the parapoxviruses orf virus and bovine papular stomatitis virus. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, A.A.; Ueda, N.; Friederichs, S.-M.; Hofmann, K.; Fraser, K.M.; Bateman, T.; Fleming, S.B. Comparative analysis of genome sequences of three isolates of Orf virus reveals unexpected sequence variation. Virus Res. 2006, 116, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hautaniemi, M.; Ueda, N.; Tuimala, J.; Mercer, A.A.; Lahdenpera, J.; McInnes, C.J. The genome of pseudocowpoxvirus: Comparison of a reindeer isolate and a reference strain. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 1560–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, P.P.; Silva, P.M.; Schnellrath, L.C.; Jesus, D.M.; Hu, J.; Yang, Y.; Renne, R.; Attias, M.; Condit, R.C.; Moussatché, N.; et al. Biological characterization and next-generation genome sequencing of the unclassified cotia virus SPAn232 (Poxviridae). J. Virol. 2012, 86, 5039–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratke, K.A.; McLysaght, A.; Rothenburg, S. A survey of host range genes in poxvirus genomes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2013, 14, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senkevich, T.G.; Koonin, E.V.; Bugert, J.J.; Darai, G.; Moss, B. The genome of molluscum contagiosum virus: Analysis and comparison with other poxviruses. Virology 1997, 233, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, C.L.; Tulman, E.R.; Delhon, G.; Lu, Z.; Viljoen, G.J.; Wallace, D.B.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. Genome of crocodilepox virus. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 4978–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, C.J.; Wood, A.R.; Thomas, K.; Sainsbury, A.W.; Gurnell, J.; Dein, J.; Nettleton, P.F. Genomic characterization of a novel poxvirus contributing to the decline of the red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) in the UK. J. Gen. Virol. 2006, 87, 2115–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, C.L.; Tulman, E.R.; Lu, Z.; Oma, E.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. The genome of Melanoplus sanguinipes entomopoxvirus. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bawden, A.L.; Glassberg, K.J.; Diggans, J.; Shaw, R.; Farmerie, W.; Moyer, R.W. Complete genomic sequence of the Amsacta moorei entomopoxvirus: Analysis and comparison with other poxviruses. Virology 2000, 274, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thézé, J.; Takatsuka, J.; Li, Z.; Gallais, J.; Doucet, D.; Arif, B.; Nakai, M.; Herniou, E.A. New insights into the evolution of Entomopoxvirinae from the complete genome sequences of four entomopoxviruses infecting Adoxophyes honmai, Choristoneura biennis, Choristoneura rosaceana, and Mythimna separata. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 7992–8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosavi, L.K.; Cammett, T.J.; Desrosiers, D.C.; Peng, Z.-Y. The ankyrin repeat as molecular architecture for protein recognition. Protein Sci. 2004, 13, 1435–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jernigan, K.K.; Bordenstein, S.R. Ankyrin domains across the Tree of Life. Peer J. 2014, 264, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Breeden, L.; Nasmyth, K. Similarity between cell-cycle genes of budding yeast and fission yeast and the Notch gene of Drosophila. Nature 1987, 329, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lux, S.; John, K.M.; Bennett, V. Analysis of cDNA for human erythrocyte ankyrin indicates a repeated structure with homology to tissue differentiation and cell-cycle control proteins. Nature 1990, 344, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, V.; Baines, A.J. Spectrin and ankyrin-based pathways: Metazoan inventions for integrating cells into tissues. Phys. Rev. 2001, 81, 1353–1392. [Google Scholar]

- Michaely, P.; Tomchick, D.R.; Machius, M.; Anderson, R.G.W. Crystal structure of a 12 ANK repeat stack from human ankyrinR. Peer J. 2002, 21, 6387–6396. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, S.R.; Mohler, P.J. Ankyrin protein networks in membrane formation and stabilization. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009, 13, 4364–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.; Zhang, Y. Molecular evolution of the ankyrin gene family. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006, 23, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, V.; Lorenzo, D.N. Spectrin- and ankyrin-based membrane domains and the evolution of vertebrates. Curr. Top. Membr. 2013, 72, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gaudet, R. A primer on ankyrin repeat function in TRP channels and beyond. Mol. Biosyst. 2008, 4, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Mahajan, A.; Tsai, M.-D. Ankyrin repeat: A unique motif mediating protein-protein interactions. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 15168–15178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Meng, X.; Xiang, Y.; Deng, J. Structure function studies of vaccinia virus host range protein K1 reveal a novel functional surface for ankyrin repeat proteins. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 3331–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Xiang, Y. Vaccinia virus K1L protein supports viral replication in human and rabbit cells through a cell-type-specific set of its ankyrin repeat residues that are distinct from its binding site for ACAP2. Virology 2006, 353, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, M.; Kim, E. The SHANK family of scaffold proteins. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113, 1851–1856. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guilmatre, A.; Huguet, G.; Delorme, R.; Bourgeron, T. The emerging role of SHANK repeat genes in neuropsychiatric disorders. Dev. Neurobiol. 2013, 74, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, M.D.; Harrison, S.C. Structure of an IκBα/NF-κB complex. Cell 1998, 95, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huxford, T.; Ghosh, G. A structural guide to proteins of the NF-κB signalling module. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubman, O.Y.; Kopan, R.; Waksman, G.; Korole, S. The crystal structure of a partial mouse Notch-1 ankyrin domain: Repeats 4 through 7 preserve an ankyrin fold. Protein Sci. 2005, 14, 1274–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Guo, Y. Gankyrin oncoprotein: Structure, function, and involvement in cancer. Curr. Chem. Biol. 2010, 4, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, S.J.; Smith, S. Tankyrase function at telomeres, spindle poles, and beyond. Biochemie 2008, 90, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakinuma, N.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Roy, B.C.; Kiyama, R. KANK repeat proteins: Structure, functions and diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 2651–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojic, S.; Radojkovic, D.; Faulkner, G. Muscle ankyrin repeat proteins: Their role in striated muscle function in health and disease. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2011, 48, 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Yu, Y.; Yang, J. Structural biology of TRP channels. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2011, 704, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Khodor, S.; Price, C.T.; Kalia, A.; Kwaik, Y.A. Functional diversity of ankyrin repeats in microbial proteins. Trends Micro 2010, 18, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, A.A.; Fleming, S.B.; Ueda, N. F-Box-like domains are present in most poxvirus ankyrin repeat proteins. Virus Genes 2005, 31, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, C.; Sen, P.; Hofmann, K.; Ma, L.; Goebl, M.; Harper, J.W.; Elledge, S.J. SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell 1996, 86, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardozo, T.; Pagano, M. The SCF ubiquitin ligase: Insights into a molecular machine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarikas, A.; Hartmann, T.; Pan, Z.-Q. The cullin protein family. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Cardozo, T.; Lovering, R.C.; Elledge, S.J.; Pagano, M.; Harper, J.W. Systematic analysis and nomenclature of mammalian F-box proteins. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 2573–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duda, D.M.; Borg, L.A.; Scott, D.C.; Hunt, H.W.; Hammel, M.; Schulman, B.A. Structural insights into NEDD8 activation of cullin-RING ligases: Conformational control of conjugation. Cell 2008, 19, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydeard, J.R.; Schulman, B.A.; Harper, J.W. Building and remodelling Cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligases. EMBO Rep. 2013, 14, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnberg, S.; Seet, B.T.; Pawson, T.; Fleming, S.B.; Mercer, A.A. Poxvirus ankyrin repeat proteins are a unique class of F-box proteins that associate with cellular SCF1 ubiquitin ligase complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 105, 10955–10960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-J.; Hsiao, J.-C.; Sonnberg, S.; Chiang, C.-T.; Yang, M.-H.; Tzou, D.-L.; Mercer, A.A.; Chang, W. Poxvirus host range protein CP77 contains an F-box-like domain that is necessary to suppress NF-κB activation by tumor necrosis factor alpha but is independent of its host range function. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 4140–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.R.; Rahmana, M.M.; Lanchbury, J.S.; Shattuck, D.; Neff, C.; Dufford, M.; van Buuren, N.; Fagan, K.; Barry, M.; Smith, S.; et al. Proteomic screening of variola virus reveals a unique NF-κB inhibitor that is highly conserved among pathogenic orthopoxviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 9045–9050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.R.; Rahmana, M.M.; Rice, A.; Moyer, R.W.; Werden, S.J.; McFadden, G. Cowpox virus expresses a novel ankyrin repeat NF-κB inhibitor that controls inflammatory cell influx into virus-infected tissues and is critical for virus pathogenesis. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 9223–9236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperling, K.M.; Schwantes, A.; Schnierle, B.S.; Sutter, G. The highly conserved orthopoxvirus 68k ankyrin-like protein is part of a cellular SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Virology 2008, 374, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Buuren, N.; Couturier, B.; Xiong, Y.; Barry, M. Ectromelia virus encodes a novel family of F-box proteins that interact with the SCF complex. J. Virol. 2008, 83, 9917–9927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanié, S.; Gelfi, J.; Bertagnoli, S.; Camus-Bouclainville, C. MNF, an ankyrin repeat protein of myxoma virus, is part of a native cellular SCF complex during viral infection. Virol. J. 2010, 7, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werden, S.J.; Lanchbury, J.; Shattuck, D.; Neff, C.; Dufford, M.; McFadden, G. The myxoma virus M-T5 ankyrin repeat host range protein is a novel adaptor that coordinately links the cellular signalling pathways mediated by Akt and Skp1 in virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 12068–12083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnberg, S.; Fleming, S.B.; Mercer, A.A.G. A truncated two-α-helix F-box present in poxvirus ankyrin-repeat proteins is sufficient for binding the SCF1 ubiquitin ligase complex. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 1224–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, B.A.; Carrano, A.C.; Jeffrey, P.D.; Bowen, Z.; Kinnucan, E.R.E.; Finnin, M.S.; Elledge, S.J.; Harper, J.W.; Pagano, M.; Pavletich, N.P. Insights into SCF ubiquitin ligases from the structure of the Skp1-Skp2 complex. Nature 2000, 408, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Xu, G.; Schulman, B.A.; Jeffrey, P.D.; Harper, J.W.; Pavletich, N.P. Structure of a β-TrCP1-Skp1-β-catenin complex: Destruction motif binding and lysine specificity of the SCF β–T rCP 1 ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutter, G.; Ramsey-Ewing, A.; Rosales, R.; Moss, B. Stable expression of the vaccinia virus K1L gene in rabbit cells complements the host range defect of a vaccinia virus mutant. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 4109–4116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perkus, M.E.; Goebel, S.J.-J.; Davis, S.W.; Johnson, G.P.; Limbach, K.; Norton, E.K.; Paolelti, E. Vaccinia virus host range genes. Virology 1990, 179, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muniz, J.R.C.; Guo, K.; Kershaw, N.J.; Ayinampudi, V.; von Delft, F.; Babon, J.J.; Bullock, A.N. Molecular architecture of the ankyrin SOCS box family of Cul5-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligases. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 425, 3166–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrickson, R.C.; Wang, C.; Hatcher, E.L.; Lefkowitz, E.J. Orthopoxvirus genome evolution: The role of gene loss. Viruses 2010, 2, 1933–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, A.L.; Irausquin, S.; Friedman, R. The evolutionary biology of poxviruses. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2010, 10, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoine, G.; Scheiflinger, F.; Dorner, F.; Falkner, F.G. The complete genomic sequence of the modified vaccinia Ankara strain: Comparison with other orthopoxviruses. Virology 1998, 244, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossman, K.; Lee, S.F.; Barry, M.; Boshkov, L.; McFadden, G. Disruption of M-T5, a novel myxoma virus gene member of the poxvirus host range superfamily, results in dramatic attenuation of myxomatosis in infected European rabbits. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 4394–4410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marschang, R.E. Viruses infecting reptiles. Viruses 2011, 3, 2087–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odom, M.R.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Lefkowitz, E.J. Poxvirus protein evolution: Family wide assessment of possible horizontal gene transfer events. Virus Res. 2009, 144, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werren, J.H.; Richards, S.; Desjardins, C.A.; Niehuis, O.; Gadau, J.; Colbourne, J.K.; Beukeboom, L.W.; Desplan, C.; Elsik, C.G.; Grimmelikhuijzen, C.J.P.; et al. Functional and evolutionary insights from the genomes of three parasitoid Nasonia species. Science 2010, 327, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, N.-H.; Kim, H.-R.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, J.; Cha, S.; Kim, S.-Y.; Darby, A.C.; Fuxelius, H.H.; Yin, J.; et al. The Orientia tsutsugamushi genome reveals massive proliferation of conjugative type IV secretion system and host-cell interaction genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 7981–7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, C.-K.; Kwon, Y.-J.; Ha, N.-Y.; Cho, B.A.; Kim, J.-M.; Kwon, E.-K.; Kim, Y.-S.; Choi, M.-S.; Kim, I.-S.; Cho, N.-H. Multiple Orientia tsutsugamushi ankyrin repeat proteins interact with SCF1 ubiquitin ligase complex and eukaryotic elongation factor 1a. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e105652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, S.A.; Rahman, M.M.; McFadden, G. Recombinant myxoma virus lacking all poxvirus ankyrin-repeat proteins stimulates multiple cellular anti-viral pathways and exhibits a severe decrease in virulence. Virology 2014, 464–465, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laidlaw, S.M.; Skinner, M.A. Comparison of the genome sequence of FP9, an attenuated, tissue culture-adapted European strain of fowlpox virus, with those of virulent American and European viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2004, 85, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, S.B.; Lyttle, D.J.; Sullivan, J.T.; Andrew, A.; Mercer, A.A.; Robinson, A.J. Genomic analysis of a transposition-deletion variant of orf virus reveals a 3.3 kbp region of non-essential DNA. J. Gen. Virol. 1995, 76, 2969–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drillien, R.; Koehren, F.; Kirn, A. Host range deletion mutant of vaccinia virus defective in human cell. Virology 1981, 111, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, R.R.; Terajima, M. Vaccinia virus K1L protein mediates host-range function in RK-13 cells via ankyrin repeat and may interact with a cellular GTPase-activating protein. Virus Res. 2005, 114, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Jiang, C.; Arsenio, J.; Dick, K.; Cao, J.; Xiang, Y. Vaccinia virus K1L and C7L inhibit antiviral activities induced by type I interferons. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 10627–10636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shisler, J.L.; Jin, X.-L. The vaccinia virus K1L gene product inhibits host NF-κB activation by preventing IκBα degradation. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 3553–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, K.L.; Patel, S.; Xiang, Y.; Shisler, J.-L. The effect of the vaccinia K1 protein on the PKR-eIF2α pathway in RK13 and HeLa cells. Virology 2009, 394, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, K.L.; Langland, J.O.; Shisler, J.L. Viral double-stranded RNAs from vaccinia virus early or intermediate gene transcripts possess PKR activating function, resulting in NF-κB activation, when the K1 protein is absent or mutated. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 7765–7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, G.; Bowie, A.G. Innate immune activation of NF-κB and its antagonism by poxviruses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014, 25, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.R.; McFadden, G. NF-κB inhibitors: Strategies from poxviruses. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 3125–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, G. Poxvirus tropism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, A.R.; Schwab, M.; Tyers, M. A hitchhiker’s guide to the cullin ubiquitin ligases: SCF and its kin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1695, 133–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petroski, M.D.; Deshaies, R.J. Function and regulation of Cullin-Ring ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, J.B.; Wang, G.; Barrett, J.W.; Nazarian, S.H.; Colwill, K.; Moran, M.; McFadden, G. Myxoma virus M-T5 protects infected cells from the stress of cell cycle arrest through its interaction with host cell Cullin-1. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 10750–10763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burles, K.; van Buuren, N.; Barry, M. Ectromelia virus encodes a family of ANK/F-box proteins that regulate NFκB. Virology 2014, 468–470, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttigieg, K.; Laidlaw, S.M.; Ross, C.; Davies, M.; Goodbourn, S.; Skinner, M.A. Genetic screen of a library of chimeric poxviruses identifies an ankyrin repeat protein involved in resistance to the avian type I interferon response. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 5028–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, J.-C.; Chao, C.-C.; Young, M.-J.; Chang, Y.-T.; Cho, E.-C.; Chang, W. A poxvirus host range protein, CP77, binds to a cellular protein, HMG20A, and regulates its dissociation from the vaccinia virus genome in CHO-K1 cells. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 7714–7728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanié, S.; Mortier, J.; Delverdier, M.; Bertagnoli, S.; Camus-Bouclainville, C. M148R and M149R are two virulence factors for myxoma virus pathogenesis in the European rabbit. Vet. Res. 2009, 40, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacek, K.; Bauer, B.; Bienkowska-Szewczyk, K.; Rziha, H.-J. Orf virus (ORFV) ANK-1 protein mitochondrial localization is mediated by ankyrin repeat motifs. Virus Genes 2014, 49, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperling, K.M.; Schwantes, A.; Staib, C.; Schnierle, B.S.; Sutter, G. The orthopoxvirus 68-kilodalton ankyrin-like protein is essential for DNA replication and complete gene expression of modified vaccinia virus Ankara in non-permissive human and murine cells. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 6029–6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laidlaw, S.M.; Robey, R.; Davies, M.; Giotis, E.S.; Ross, C.; Davies, M.; Buttigieg, K.; Goodbourn, S.; Skinner, M.A. Genetic screen of a mutant poxvirus library identifies an ankyrin repeat protein involved in blocking induction of avian type I interferon. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 5041–5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camus-Bouclainville, C.; Fiette, L.; Bouchiha, S.; Pignolet, B.; Counor, D.; Filipe, C.; Gelfi, J.; Messud-Petit, F. A virulence factor of myxoma virus colocalizes with NF-κB in the nucleus and interferes with inflammation. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 2510–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiscott, J.; Nguyen, T.L.A.; Arguello, M.; Nakhaei, P.; Paz, S. Manipulation of the nuclear factor-κB pathway and the innate immune response by viruses. Oncogene 2006, 25, 6844–6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Negrate, G. Viral interference with innate immunity by preventing NF-κB activity. Cell. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; May, M.J.; Kopp, E.B. NF-κB and Rel proteins: Evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 1998, 16, 225–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, C.J.; Wood, A.R.; Mercer, A.A. Orf virus encodes a homolog of the vaccinia virus interferon-resistance gene E3L. Virus Genes 1998, 17, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diel, D.G.; Delhon, G.; Luo, S.; Flores, E.F.; Rock, D.L. A novel inhibitor of the NF-κB signalling pathway encoded by the parapoxvirus orf virus. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 3962–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diel, D.G.; Luo, S.; Delhon, G.; Peng, Y.; Flores, E.F.; Rock, D.L. A nuclear inhibitor of NF-κB encoded by a poxvirus. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diel, D.G.; Luo, S.; Delhon, G.; Peng, Y.; Flores, E.F.; Rock, D.L. Orf virus ORFV121 encodes a novel inhibitor of NF-κB that contributes to virus virulence. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravalli, R.N.; Hu, S.; Lokensgard, J.R. Inhibition of Toll-like receptor signalling in primary murine microglia. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2008, 3, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Buuren, N.; Burles, K.; Schriewer, J.; Mehta, N.; Parker, S.; Buller, R.M.; Barry, M. EVM005: An ectromelia-encoded protein with dual roles in NF-κB inhibition and virulence. PLOS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Barrett, J.W.; Stanford, M.; Werden, S.J.; Johnston, J.B.; Gao, X.; Su, M.; Cheng, J.Q.; McFadden, G. Infection of human cancer cells with myxoma virus requires Akt activation via interaction with a viral ankyrin-repeat host range factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 4640–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werden, S.J.; Barrett, J.W.; Wang, G.; Stanford, M.M.; McFadden, G. M-T5, the ankyrin repeat, host range protein of myxoma virus, activates Akt and can be functionally replaced by cellular PIKE-A. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 2340–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, N.W.; Lee, J.E.; Liu, X.; Sweredoski, M.J.; Graham, R.L.J.; Larimore, E.A.; Rome, M.; Zheng, N.; Clurman, B.E.; Hess, S.; et al. Cand1 promotes assembly of new SCF complexes through dynamic exchange of F-Box proteins. Cell 2013, 153, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, J.T.; Fraser, K.M.; Fleming, S.B.; Robinson, A.J.; Mercer, A.A. Sequence and transcriptional analysis of an orf virus gene encoding ankyrin-like repeat sequences. Viruses Genes 1995, 9, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.R.; McInnes, C.J. Transcript mapping of the early genes of Orf virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2003, 84, 2993–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, M.; van Buuren, N.; Burles, K.; Mottet, K.; Wang, Q.; Teale, A. poxvirus exploitation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Viruses 2010, 2, 2356–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Burles, K.; Couturier, B.; Randall, C.M.H.; Shisler, J.; Barry, M. Ectromelia virus encodes a BTB/Kelch Protein, EVM150, that inhibits NF-κB signaling. J. Virol. 2014, 84, 4853–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottet, K.; Bareiss, B.; Milne, C.D.; Barry, M. The poxvirus encoded ubiquitin ligase, p28, is regulated by proteasomal degradation and autoubiquitination. Virology 2014, 468–470, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, M.; Bartee, E.; Gouveia, K.; Hovey Nerenberg, B.T.; Barrett, J.; Thomas, L.; Thomas, G.; McFadden, G.; Früh, K. The PHD/LAP-domain protein M153R of myxomavirus is an ubiquitin ligase that induces the rapid internalization and lysosomal destruction of CD4. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, M.; Fleming, S.B.; Mercer, A.A. Cell cycle deregulation by a poxvirus partial mimic of anaphase-promoting complex subunit 11. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19527–19532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, M.; Fleming, S.B.; Mercer, A.A. Orf virus cell cycle regulator, PACR, competes with subunit 11 of the anaphase promoting complex for incorporation into the complex. J. Gen Virol. 2010, 91, 3010–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teale, A.; Campbell, S.; van Buuren, N.; Magee, W.C.; Watmough, K.; Couturier, B.; Shipclark, R.; Barry, M. Orthopoxviruses require a functional ubiquitin-proteasome system for productive replication. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 2099–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satheshkumar, P.S.; Anton, L.C.; Sanz, P.; Moss, B. Inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome system prevents vaccinia virus DNA replication and expression of intermediate and late genes. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 2469–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, J.; Snijder, B.; Sacher, R.; Burkard, C.; Bleck, C.K.E.; Stahlberg, H.; Pelkmans, L.; Helenius, A. RNAi screening reveals proteasome- and Cullin3-dependent stages in vaccinia virus infection. Cell Rep. 2012, 2, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, F.I.; Bleck, C.K.E.; Reh, L.; Novy, K.; Wollscheid, B.; Helenius, A.; Stahlberg, H.; Mercer, J.A. Vaccinia virus entry is followed by core activation and proteasome-mediated release of the immunomodulatory effector VH1 from lateral bodies. Cell Rep. 2013, 4, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).