A Study on the Design of a Fault-Tolerant Consequent-Pole Hybrid Excited Machine for Electric Vehicles

Abstract

:1. Introduction

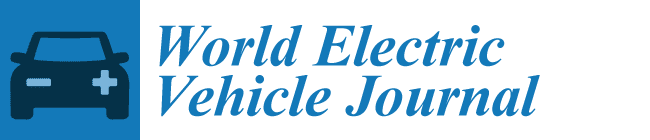

2. Machine Topology

2.1. Topology Description

2.2. Operation Principle

2.2.1. Magnetic Circuits

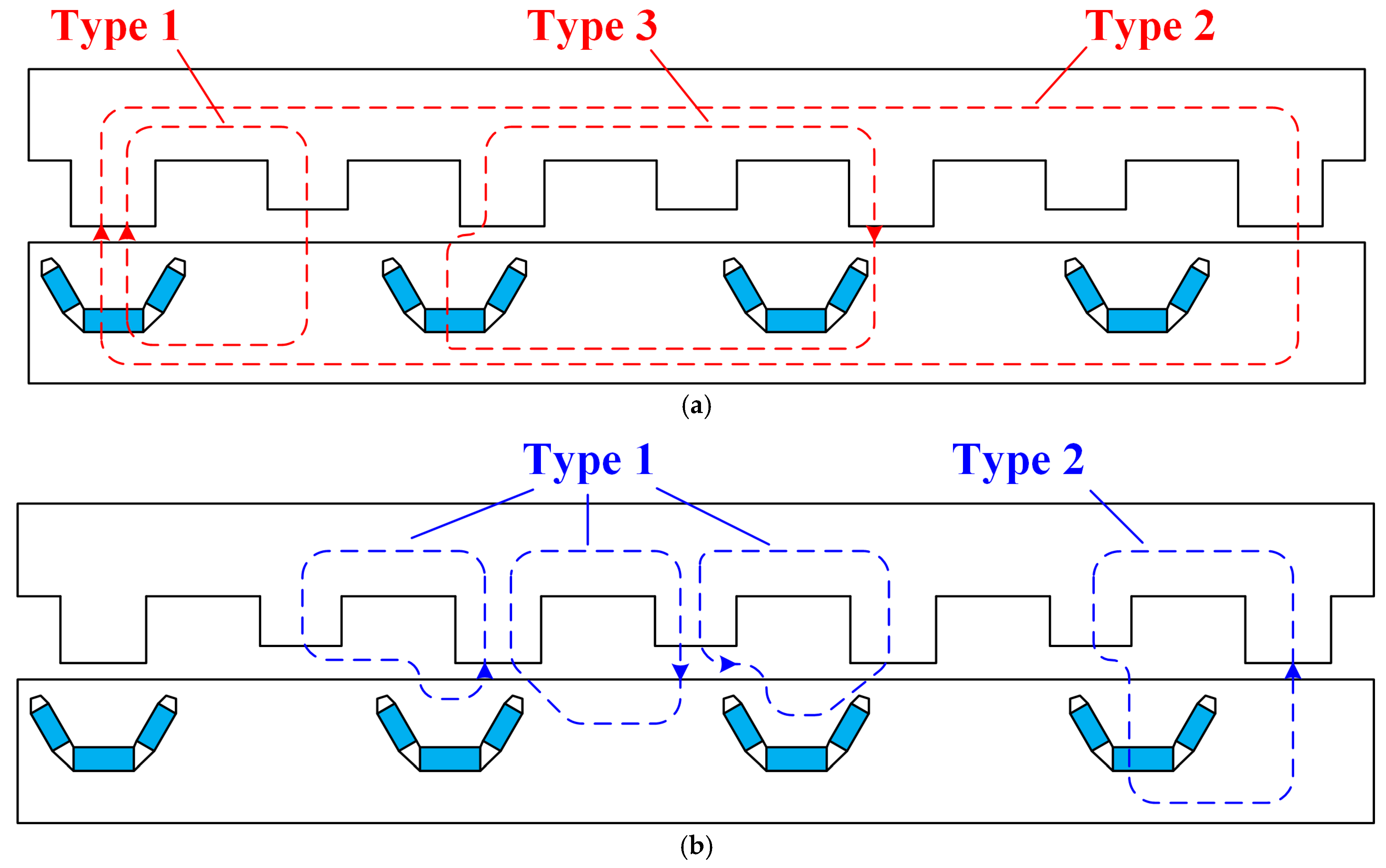

2.2.2. Field Modulation Effect

3. Machine Design

3.1. Power and Torque Equation

3.2. Slot/Pole Combination

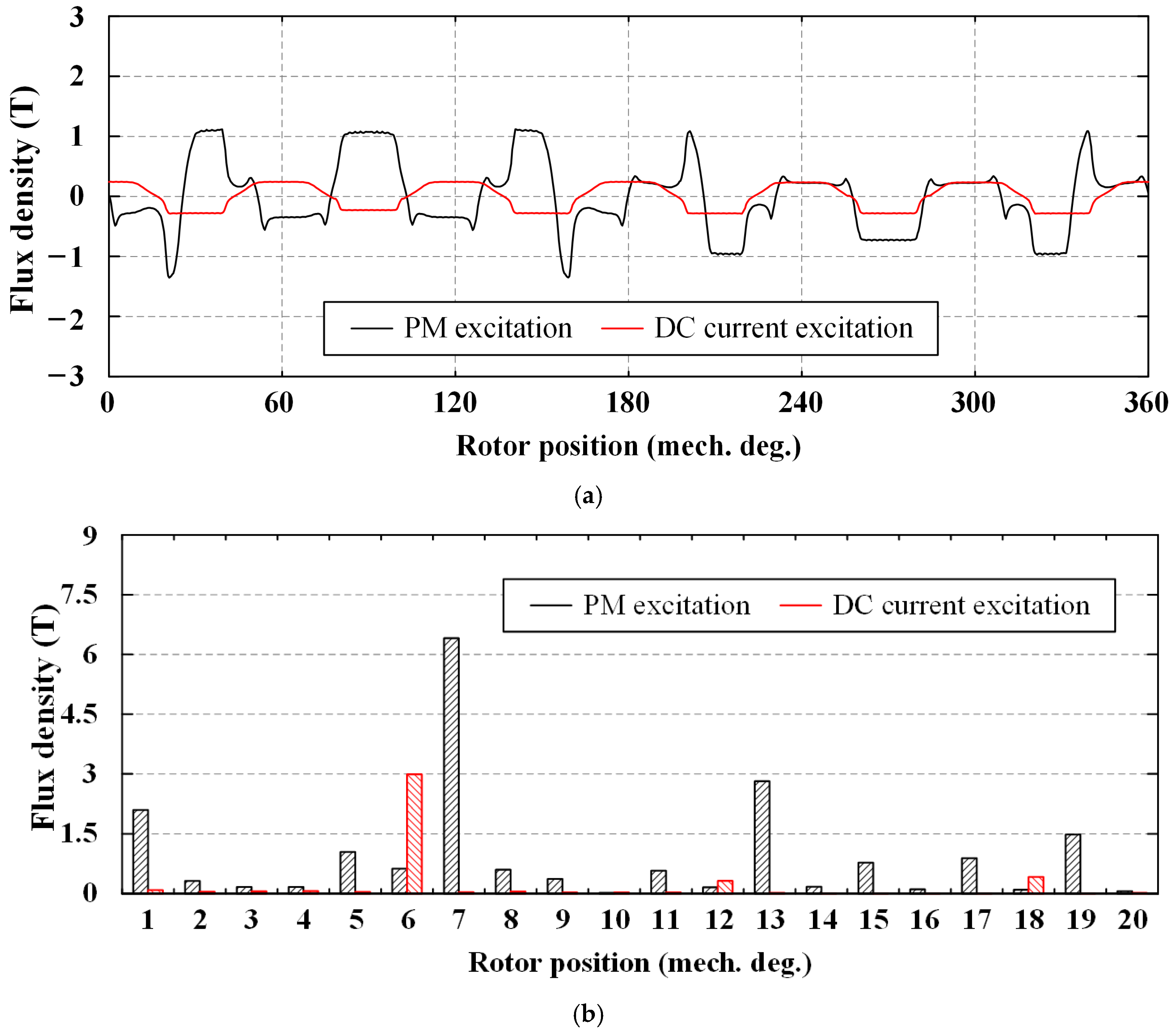

3.3. Winding Connection of Inverter

3.4. Parameter Analysis

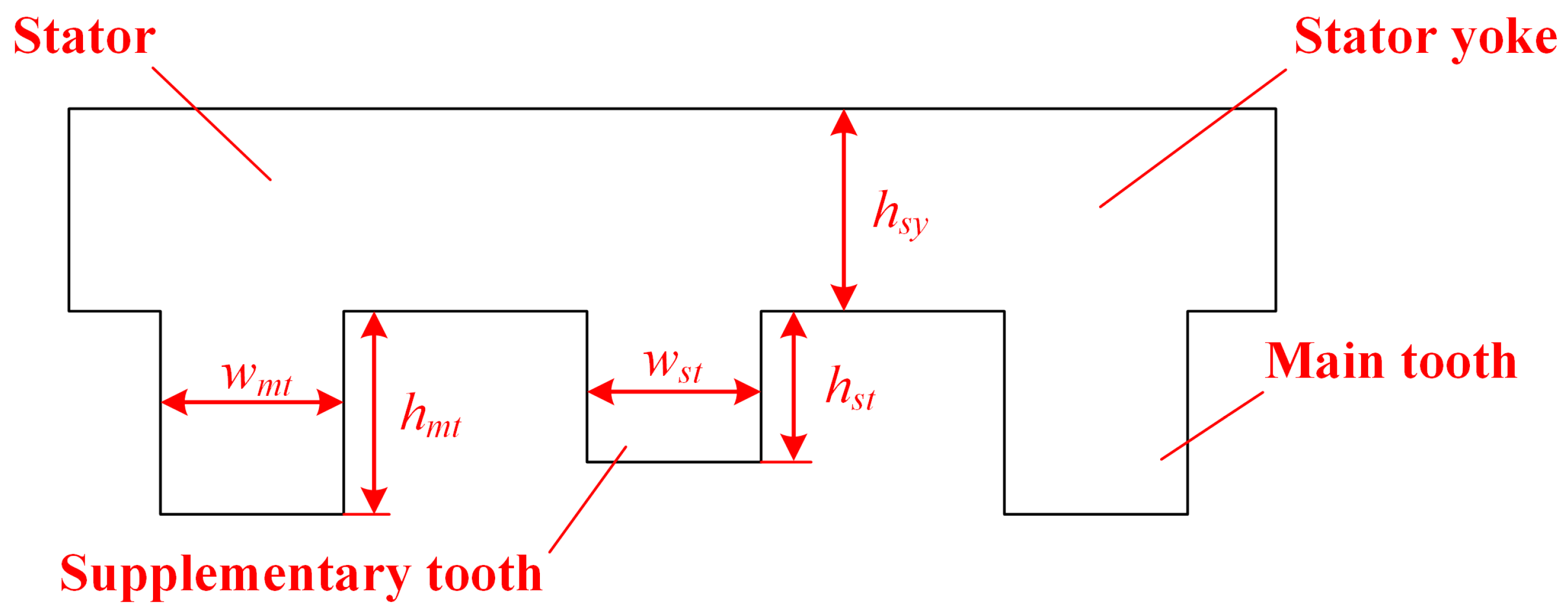

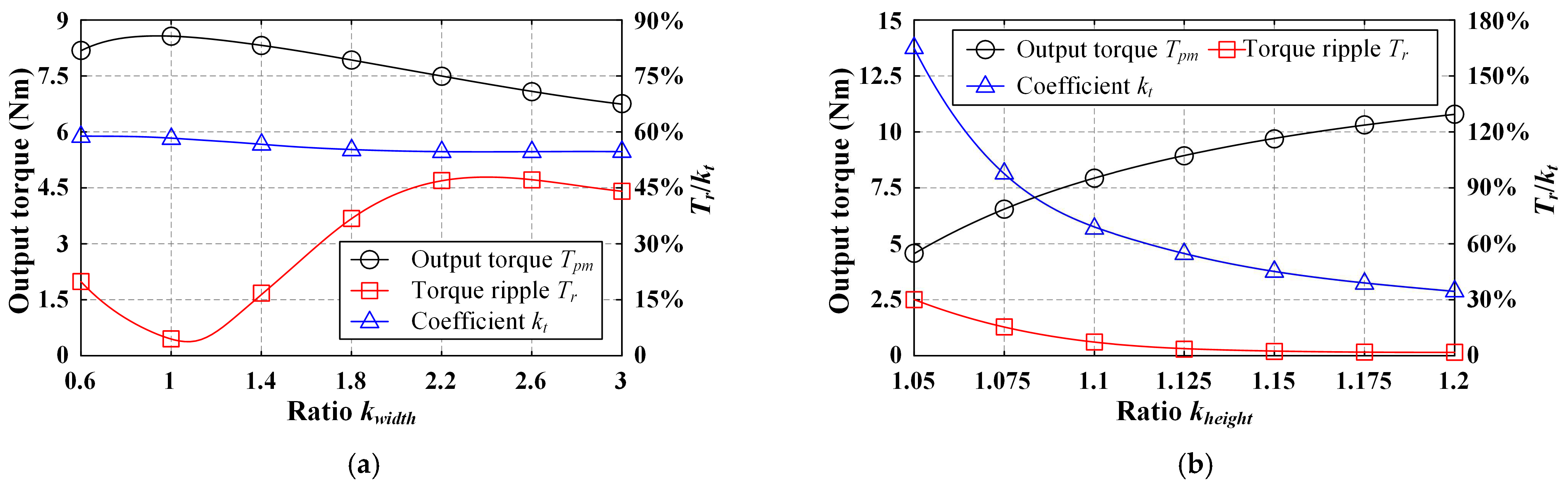

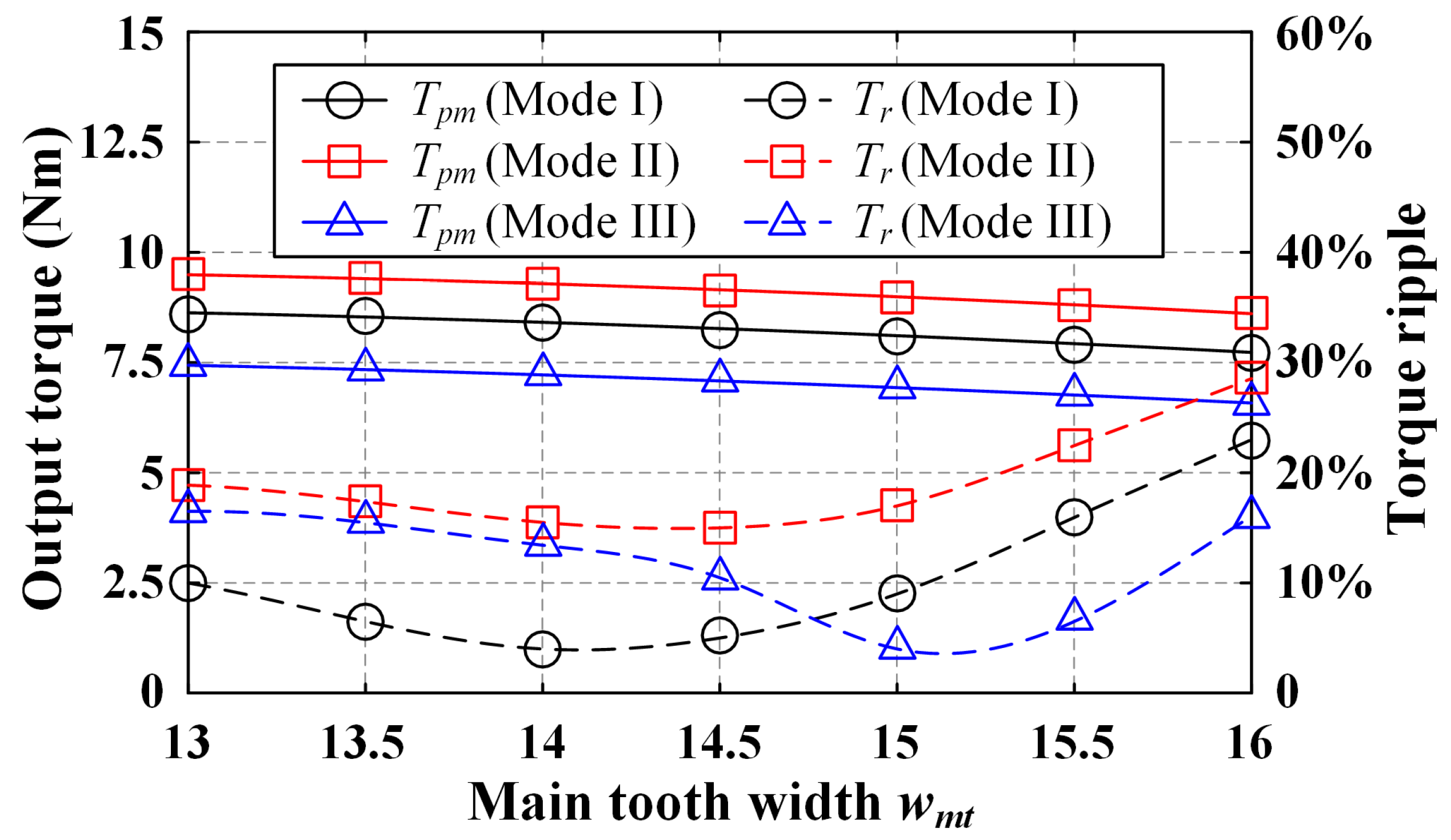

3.4.1. Stator Parameters

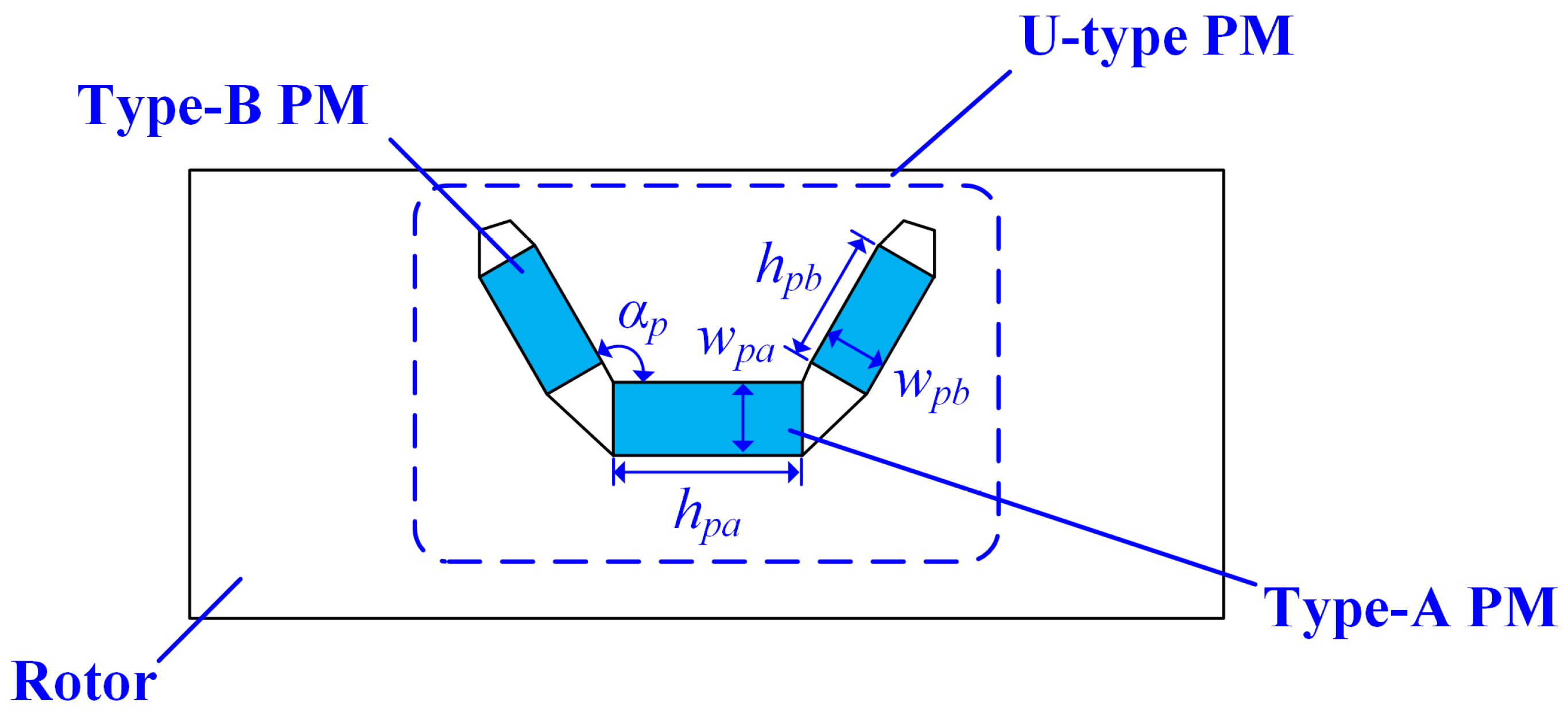

3.4.2. Rotor Parameters

4. Electromagnetic Performance

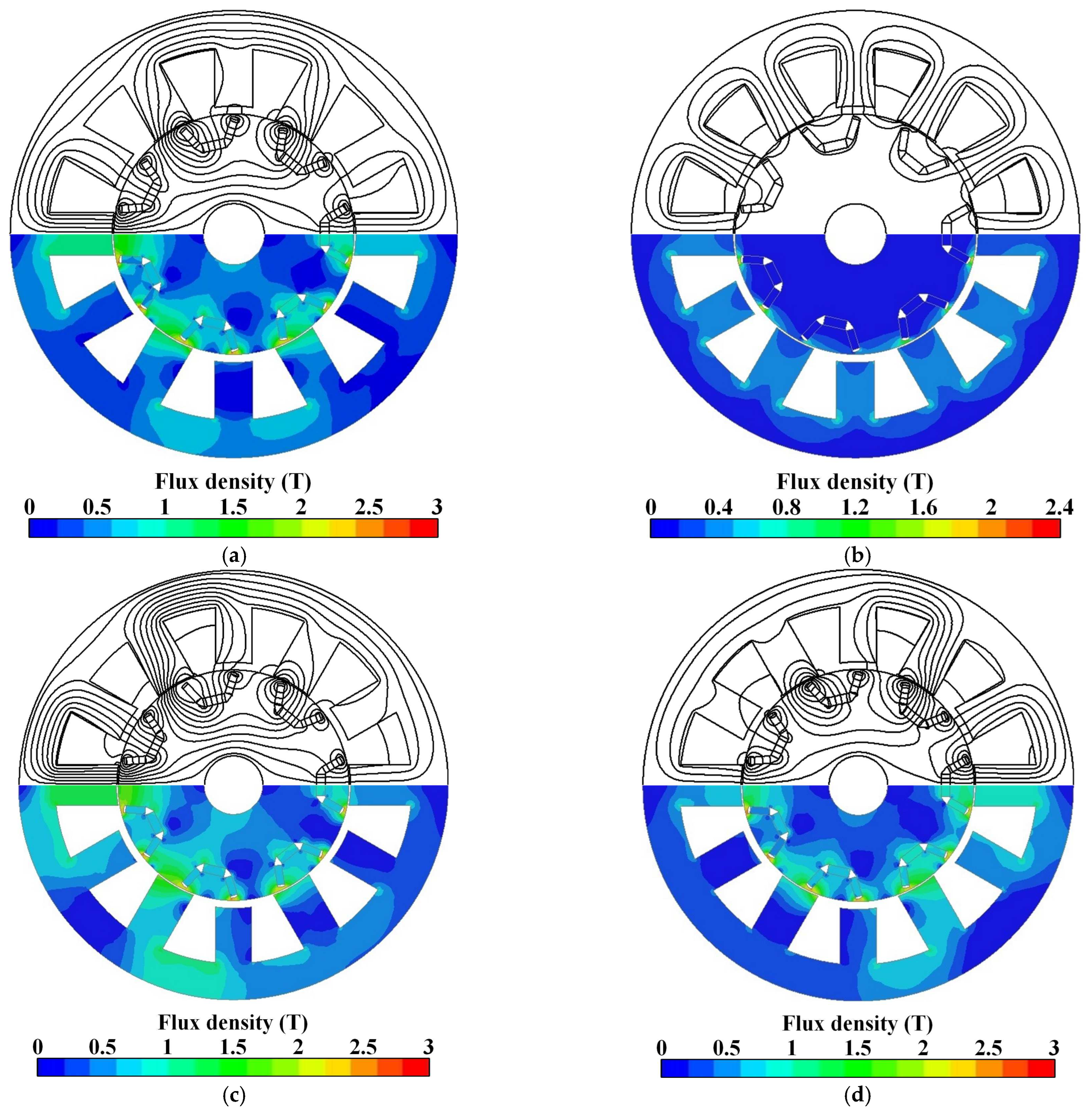

4.1. Flux Distribution

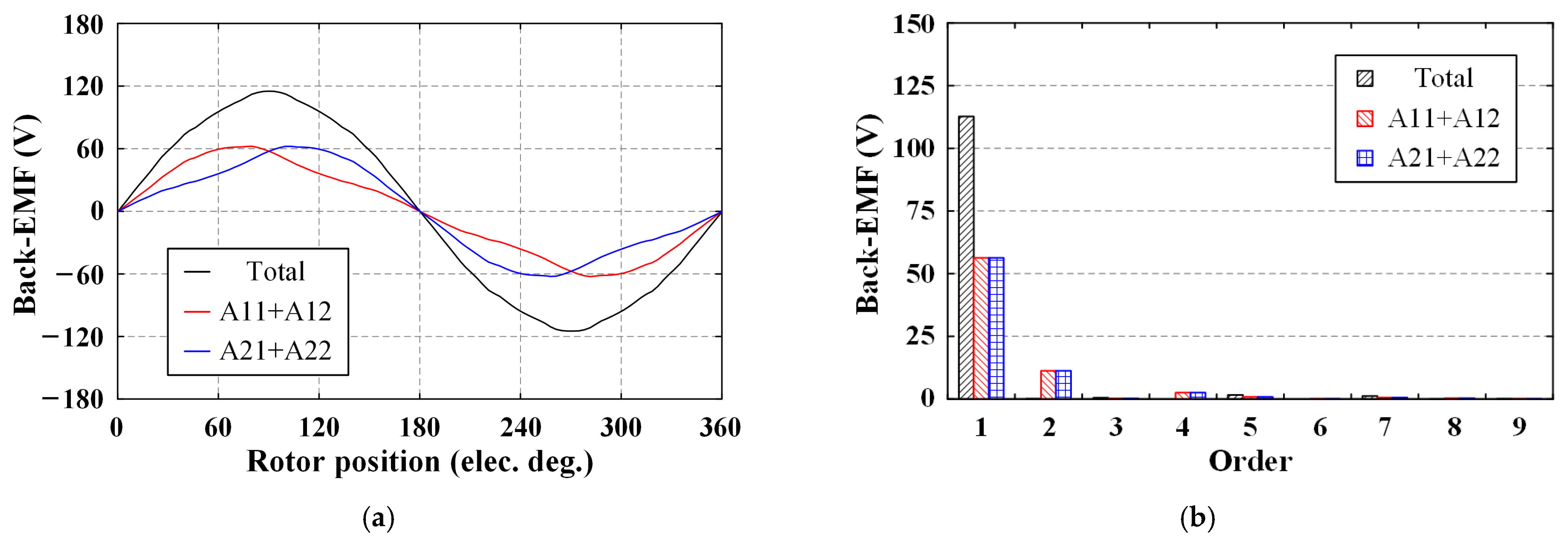

4.2. No-Load Back-EMF

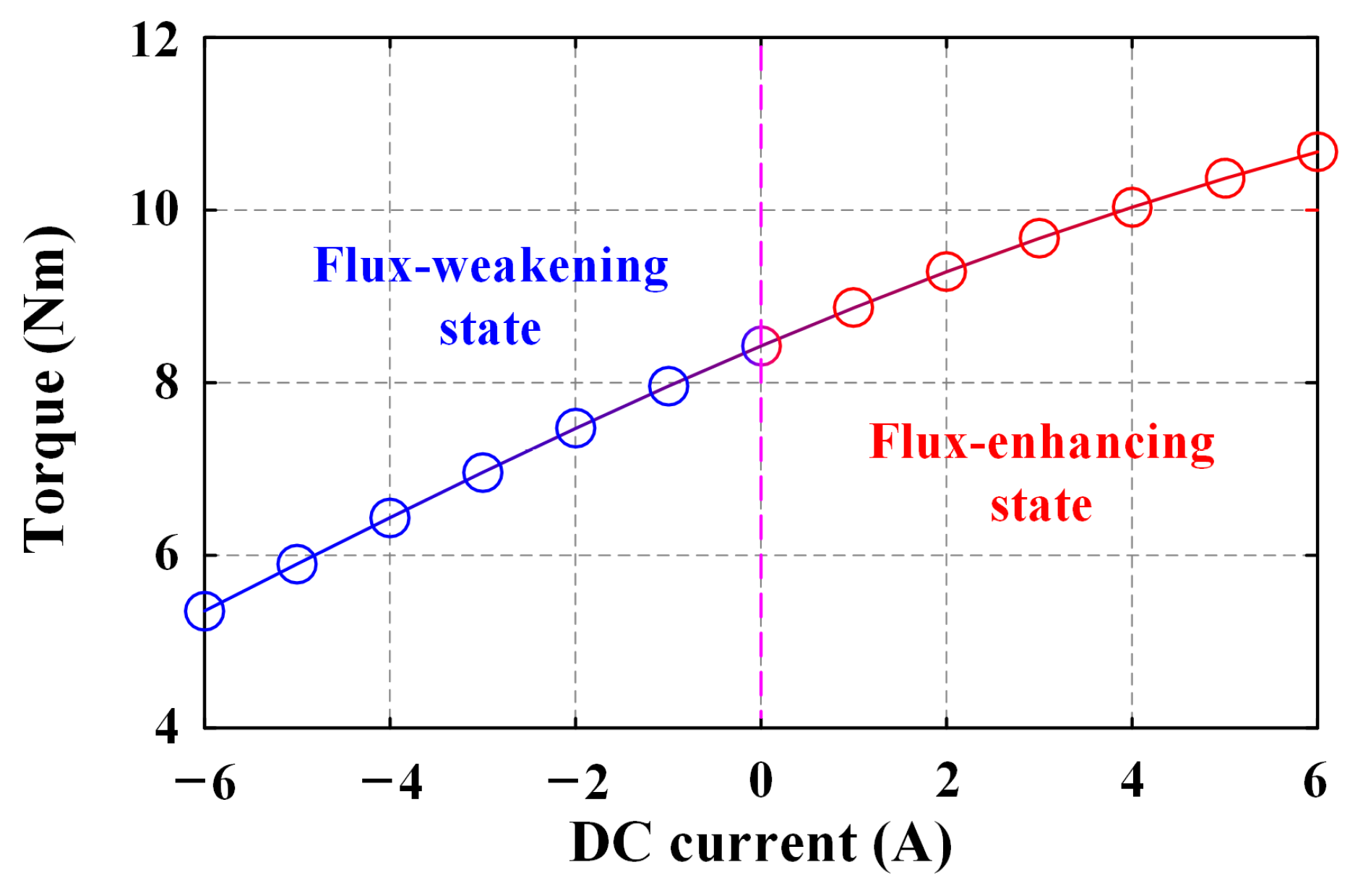

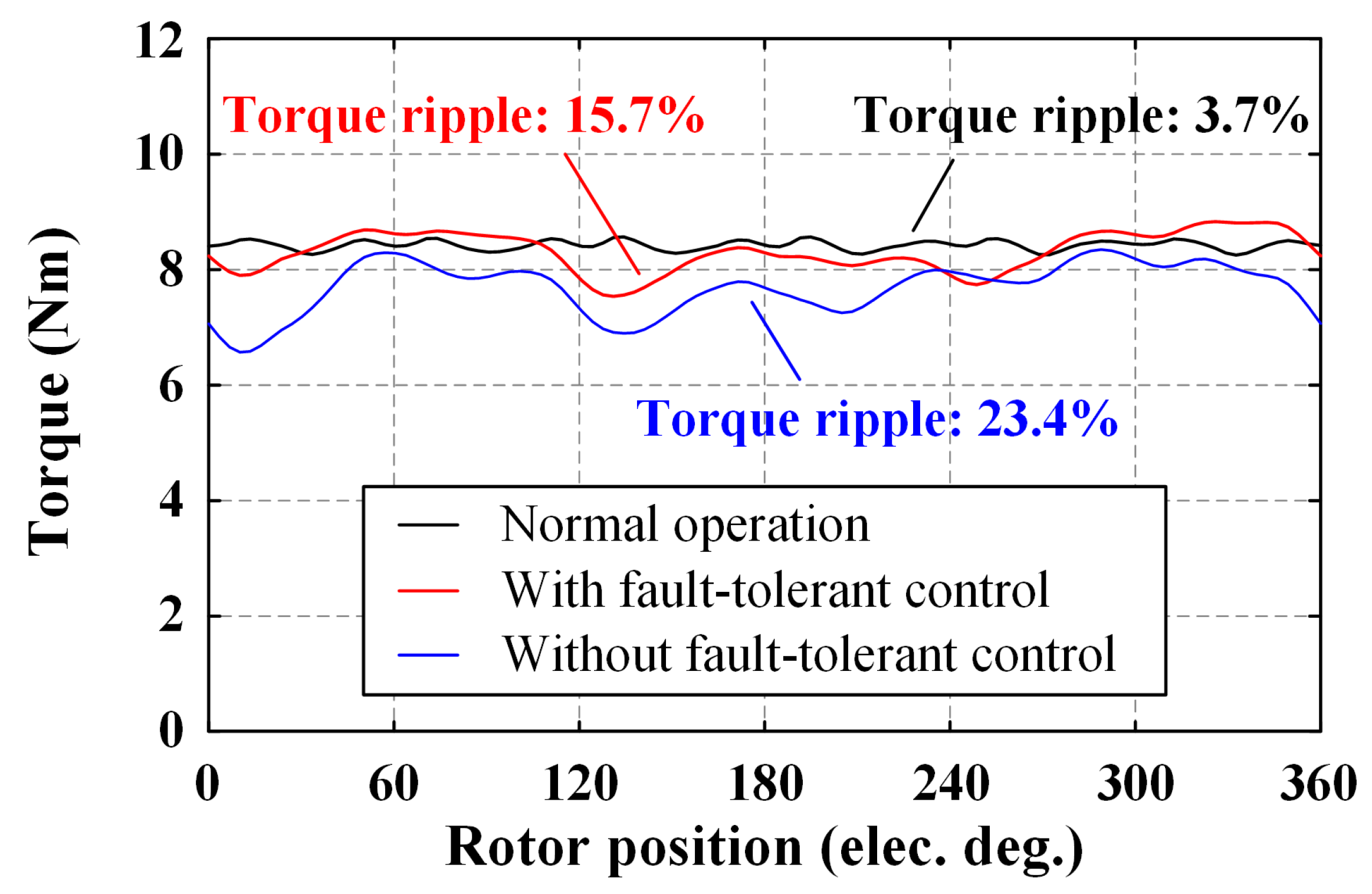

4.3. Electromagnetic Torque

4.4. Cogging Torque

4.5. Fault-Tolerant Ability

5. Experimental Verification

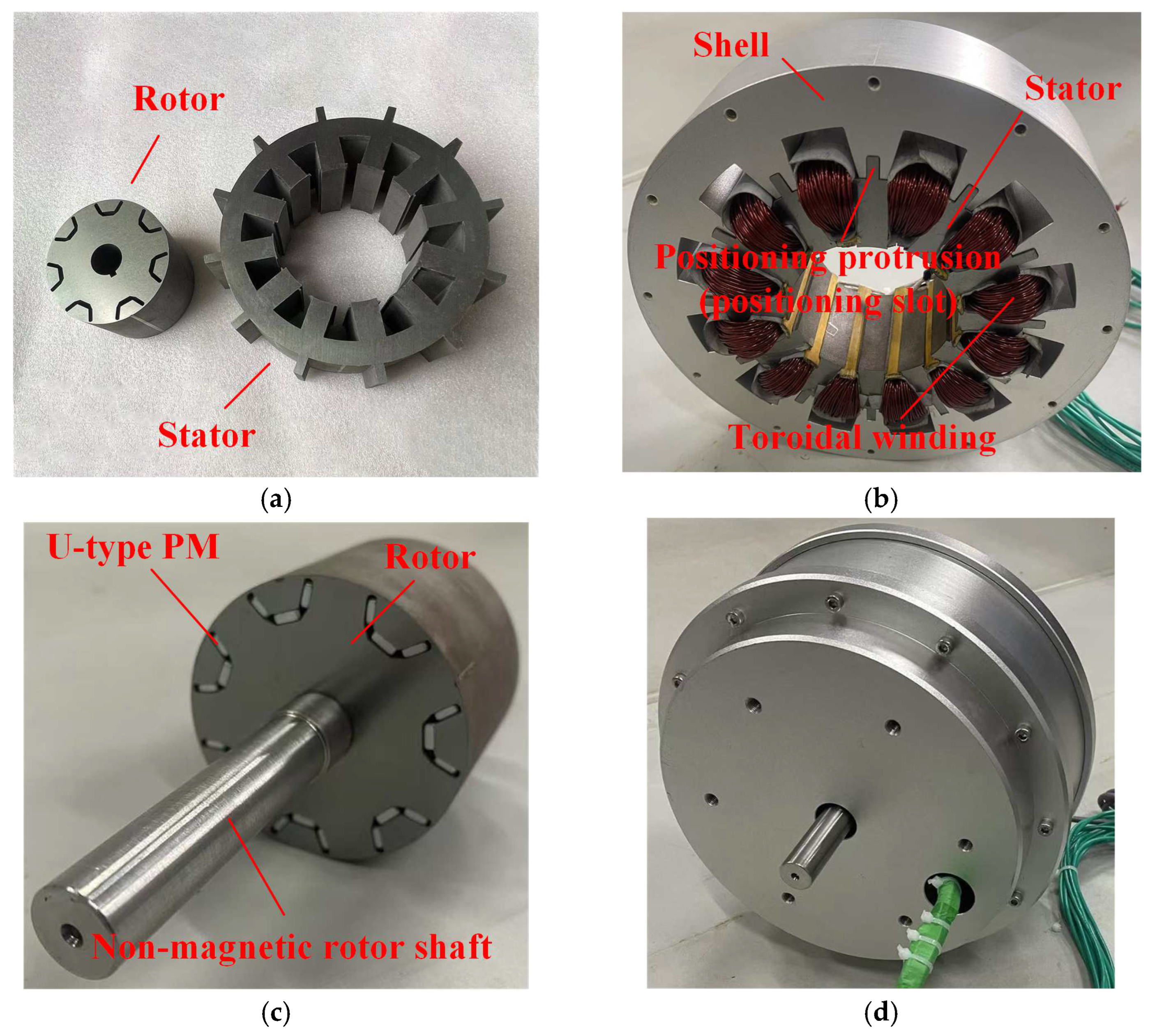

5.1. Prototype Machine and Test Platform

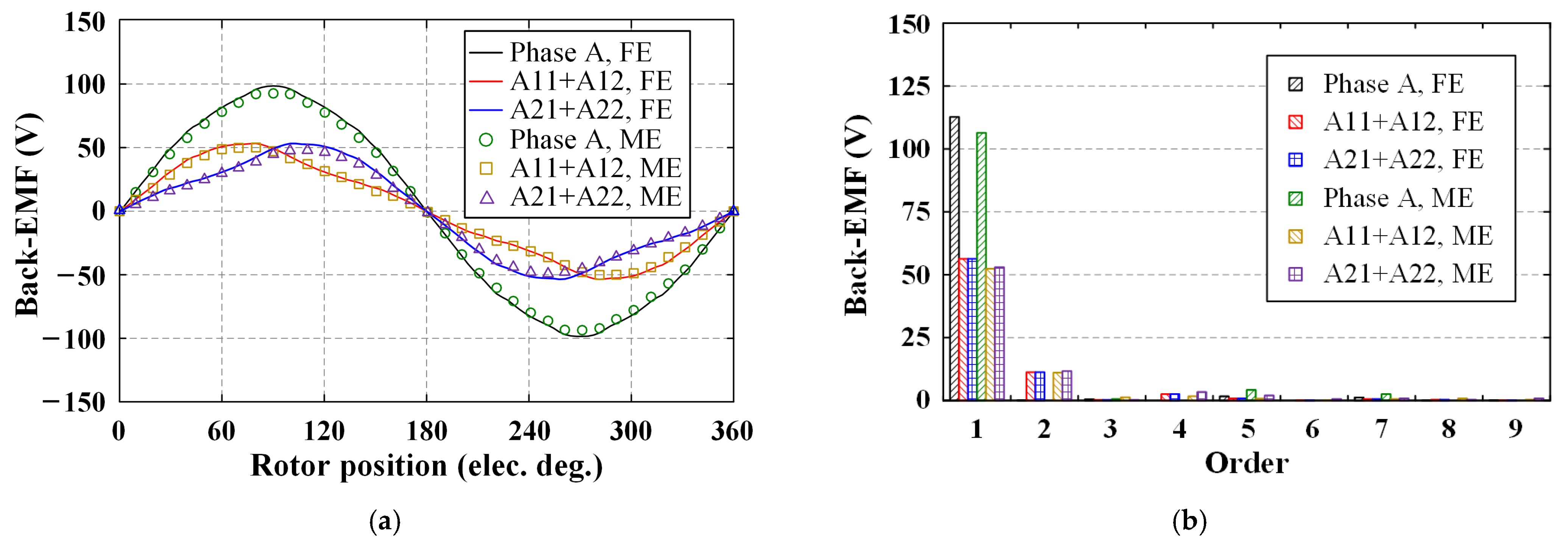

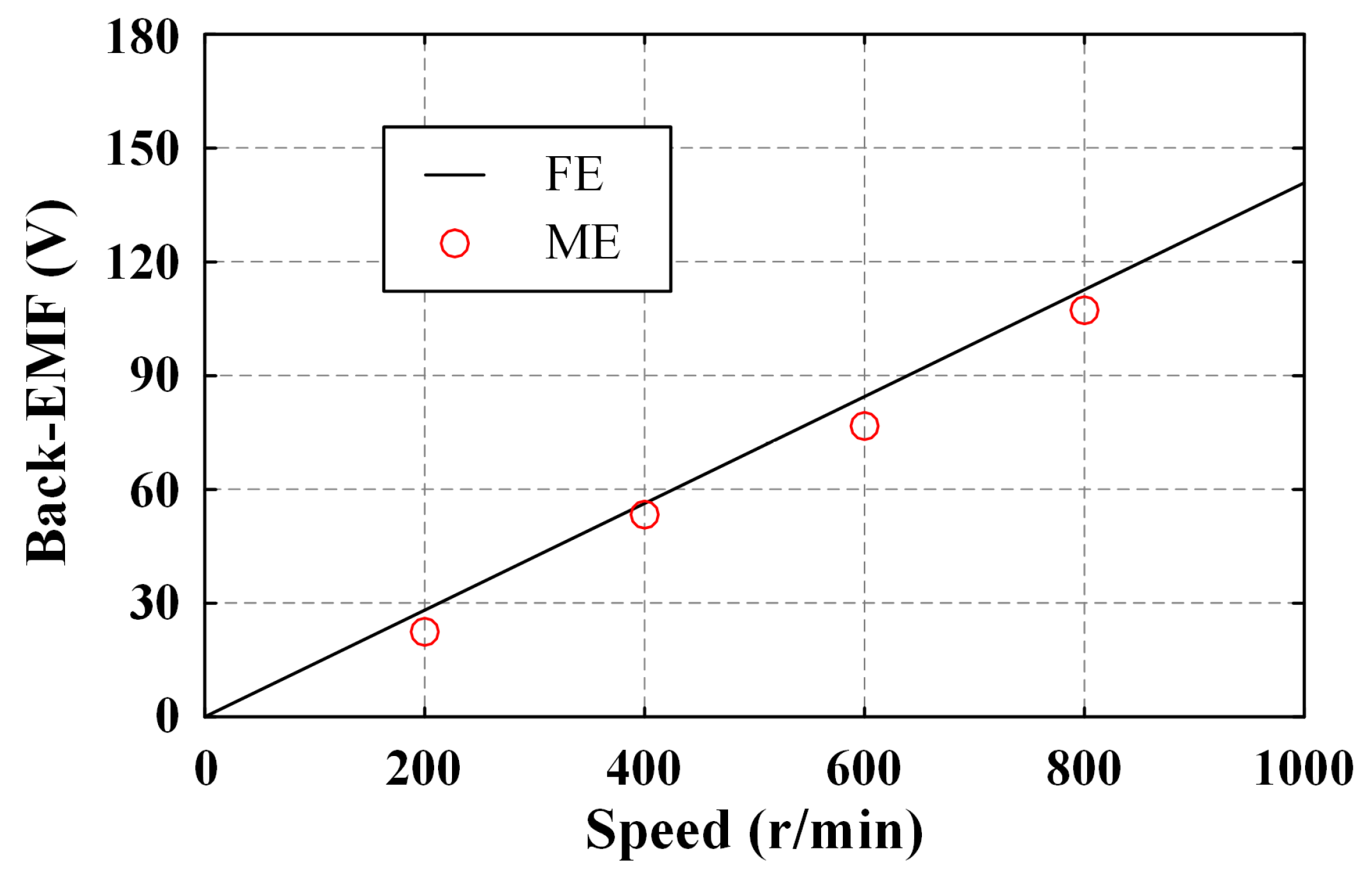

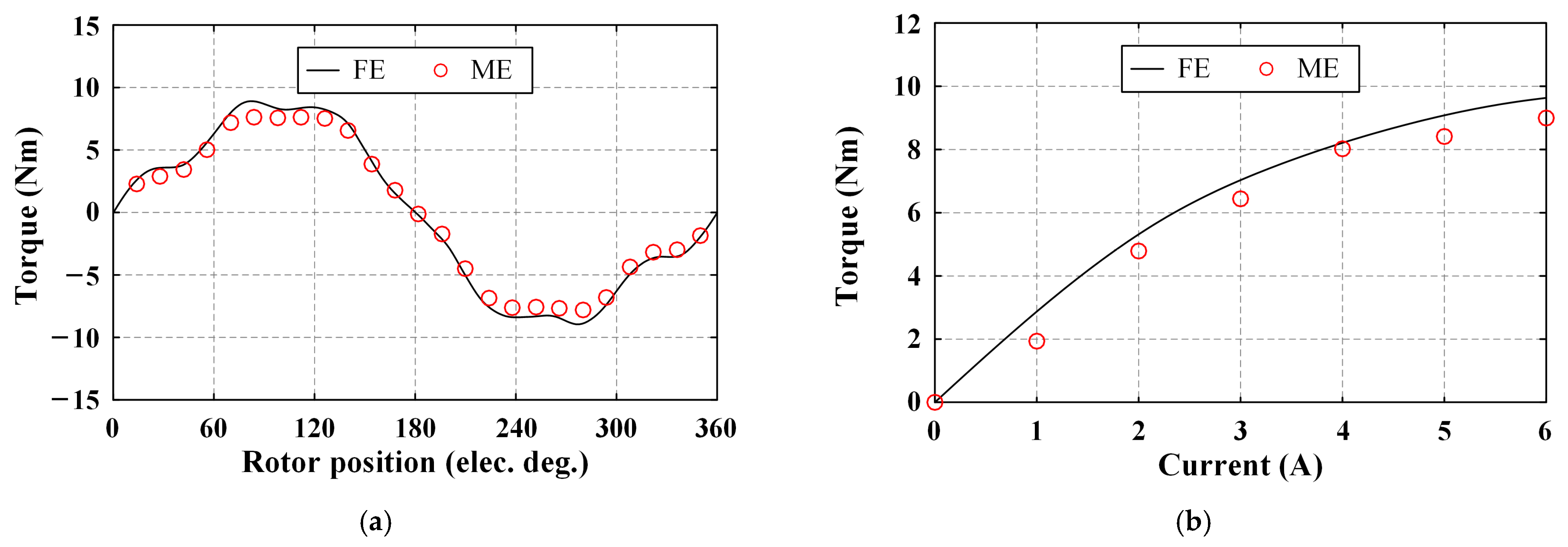

5.2. Test Result

6. Conclusions

- The brushless hybrid excitation can be achieved by a new harmonic field coupling effect, in which reliability can be improved and the manufacture cost can be decreased. In addition, good flux regulation can also be achieved with this new electromagnetic coupling effect.

- The U-type PM and the TW are located in the rotor and the stator, respectively. Therefore, good space utilization can be achieved in the FTCPHE machine.

- With the consequent-pole structure, high torque density and low PM usage can be achieved in the proposed FTCPHE machine. In addition, torque ripple under different operating statuses can all be controlled within 10%, in which the lowest torque ripple can be decreased to 3.3%.

- Both the AC and the DC can be combined in one set of integrated winding (TW). This winding structure can be significantly simplified, copper loss can be decreased, and fault-tolerant ability can be improved, which is helpful to reduce the manufacture cost and cycle.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FTCPHE | Fault-tolerant consequent-pole hybrid excited |

| PM | Permanent magnet |

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| THD | Total distortion harmonic |

| FW | Field winding |

| TW | Toroidal winding |

| AW | Armature winding |

| FE | Finite element |

| ME | Measurement |

| Back-EMF | Back electromotive force |

| LCM | Least common multiple |

References

- Tong, M.; Chen, Y.; Sun, L. An Approach to Motor Winding Optimization for HEFS Machine-Based Integrated On-Board Charging Systems. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, W.; Qu, G.; Jing, H.; Huang, J. Research on control and optimization of heavy-duty electromagnetic bearing of large-capacity energy storage flywheel. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 10th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (IPEMC2024-ECCE Asia), Chengdu, China, 17–20 May 2024; pp. 539–543. [Google Scholar]

- Souissi, A.; Abdennadher, I.; Masmoudi, A. Analytical Investigation of the Air Gap Flux Density of Surface-Mounted PMSMs With Irregular Pole Shapes. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Fan, Y.; Wu, Z. Design and Analysis of a New Hybrid-Excited Permanent Magnet Machine With Unequal Teeth. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2019, 55, 8105805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michieletto, D.; Cinti, L.; Bianchi, N. Hybrid Excitation PM Synchronous Motors: Part I—Per Unit Analysis. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2022, 37, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michieletto, D.; Cinti, L.; Bianchi, N. Hybrid Excitation PM Synchronous Motors: Part II—Finite Element Analysis. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2022, 37, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, L.; Michieletto, D.; Bianchi, N.; Bertoluzzo, M. A Comparison between Hybrid Excitation and Interior Permanent Magnet Motors. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Workshop on Electrical Machines Design, Control and Diagnosis (WEMDCD), Modena, Italy, 8–9 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ren, J.; Meng, F.; Wu, J.; Pang, X.; Liu, W.; Kong, Z. Analysis of Electromagnetic Performance of Permanent Magnet and Convex Pole Electromagnetic Hybrid Excitation Generator. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 39, 1216–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, L.; Bianchi, N.; Bertoluzzo, M. Performance and Short-Circuit Fault Analysis in Hybrid Excited and Interior PM Motors. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 39, 1412–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Liang, Y. Overview of High Overload Motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 8611–8626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Cheng, M.; Wang, S.; Hua, W. An On-Board Two-Stage Integrated Fast Battery Charger for EVs Based on a Five-Phase Hybrid-Excitation Flux-Switching Machine. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 1780–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Hua, W.; Han, P. Quantitative Evaluation of the Topologies and Electromagnetic Performances of Dual-Three-Phase Flux-Switching Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 9157–9167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Sun, X.; Yan, L.; Qi, J. Investigation of Asymmetric Consequent-Pole Hybrid Excited Flux Reversal Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 3434–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, H.; Zhu, Z.Q. Comparative Study of Series and Parallel Hybrid Excited Machines. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2020, 35, 1705–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, H.; Zhu, Z.Q. Novel Parallel Hybrid Excited Machines with Separate Stators. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2016, 31, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, H.; Ding, S.; Dai, Y.; He, C.; Wang, X. A New Partitioned Stator Field Modulation Machine With H-Shape Permanent Magnet Excitation. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2022, 58, 8106906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fan, Y.; Lorenz, R.D.; Cui, R.; Li, C.; Cheng, M. Design and Analysis of a New Five-Phase Brushless Hybrid-Excitation Fault-Tolerant Motor for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2017, 53, 3428–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Fan, Y. Design Procedure of a New Three-Segment Dual-Stator Permanent Magnet Machine for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 39, 2676–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chau, K.T.; Lin, F. A New Hybrid-Structure Machine with Multimode Fault-Tolerant Operation for Mars Rover. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2015, 51, 8207904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Mipo, J.C.; Personnaz, S. Investigation of Novel Doubly Salient Hybrid Excited Machine with Non-Overlapped Field Winding. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2021, 36, 2261–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Lu, M.; Xu, Y. Research on Air-Gap Field Modulation Effect of Torque Enhanced Hybrid Permanent Magnet Motor. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2024, 60, 8203106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Niu, Q. A Novel Hybrid-Excited Dual-PM Machine with Bidirectional Flux Modulation. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2017, 32, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, K. Analytical Determination of Optimal PM-Arc Ratio of Consequent-Pole Permanent Magnet Machines. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2018, 23, 2168–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Hua, W.; Hu, M.; Wu, Z.; Si, J.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, M. Analysis of Stator Slots and Rotor Pole Pairs Combinations of Rotor-Permanent Magnet Flux-Switching Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Yan, L.; Guo, Y.; He, X.; Gerada, C.; Chen, I.M. A Concentrated-Flux-Type PM Machine With Irregular Magnets and Iron Poles. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2024, 29, 691–702. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaee-Alam, F. On-Load Cogging Torque Calculation in Surface-Mounted Permanent Magnet Motors Using Hybrid Analytical Model. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2024, 60, 8200110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, K.; Zhang, H. Flux-Focusing Permanent Magnet Machines with Modular Consequent-Pole Rotor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 2274–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhao, W.; Ji, J.; Liu, G.; Lee, C.H.T. Generation Mechanism and Suppression Measure of Electromagnetic Vibration in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machine: A Review. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 9513–9528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | I | II | III |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current value | 4.5 A * | 5.625 A | 3.375 A |

| Current density | 5 A/mm2 | 6.25 A/mm2 | 3.75 A/mm2 |

| Item | Parameter | Item | Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rated power (W) | 700 | Stator yoke thickness (mm), hsy | 12.5 |

| Rated speed (r/min) | 800 | Stack length (mm) | 60 |

| Rated torque (Nm) | 8.4 | Width of main tooth (mm), wmt | 14 |

| Pole-pair number of rotor | 7 | Height of main tooth (mm), hmt | 21.1 |

| Pole-pair number of TW | 1 | Width of supplementary tooth (mm), wst | 12.5 |

| Pole-pair number of DC currents | 6 | Height of supplementary tooth (mm), hst | 19 |

| Number of PMs | 7 | Width of Type-A PM (mm), wpa | 7.5 |

| Number of iron cores | 7 | Height of Type-A PM (mm), hpa | 3 |

| Number of Stator slots | 12 | Width of Type-B PM (mm), wpb | 6.7 |

| Number of main/supplementary teeth | 6/6 | Height of Type-B PM (mm), hpb | 2.5 |

| Phase number | 3 × 2 | PM angle (°), αp | 120 |

| Stator outside diameter (mm) | 147 | PM material | NdFeB |

| Stator inside diameter (mm) | 80 | PM remanence | 1.2 T |

| Rotor outside diameter (mm) | 79 | PM relative permeability | 1.05 |

| Rotor inside diameter (mm) | 20 | Lamination type | 50 W 470 |

| Air-gap length * (mm) | 0.5 | Conductor turns | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qu, G.; Yu, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, W. A Study on the Design of a Fault-Tolerant Consequent-Pole Hybrid Excited Machine for Electric Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16030130

Qu G, Yu J, Li Z, Liu W. A Study on the Design of a Fault-Tolerant Consequent-Pole Hybrid Excited Machine for Electric Vehicles. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(3):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16030130

Chicago/Turabian StyleQu, Guangyu, Jinyi Yu, Zhenghan Li, and Wei Liu. 2025. "A Study on the Design of a Fault-Tolerant Consequent-Pole Hybrid Excited Machine for Electric Vehicles" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 3: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16030130

APA StyleQu, G., Yu, J., Li, Z., & Liu, W. (2025). A Study on the Design of a Fault-Tolerant Consequent-Pole Hybrid Excited Machine for Electric Vehicles. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(3), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16030130