Severe and Atypical Presentation of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy in a Pediatric Patient after a Serious Crash Injury—Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

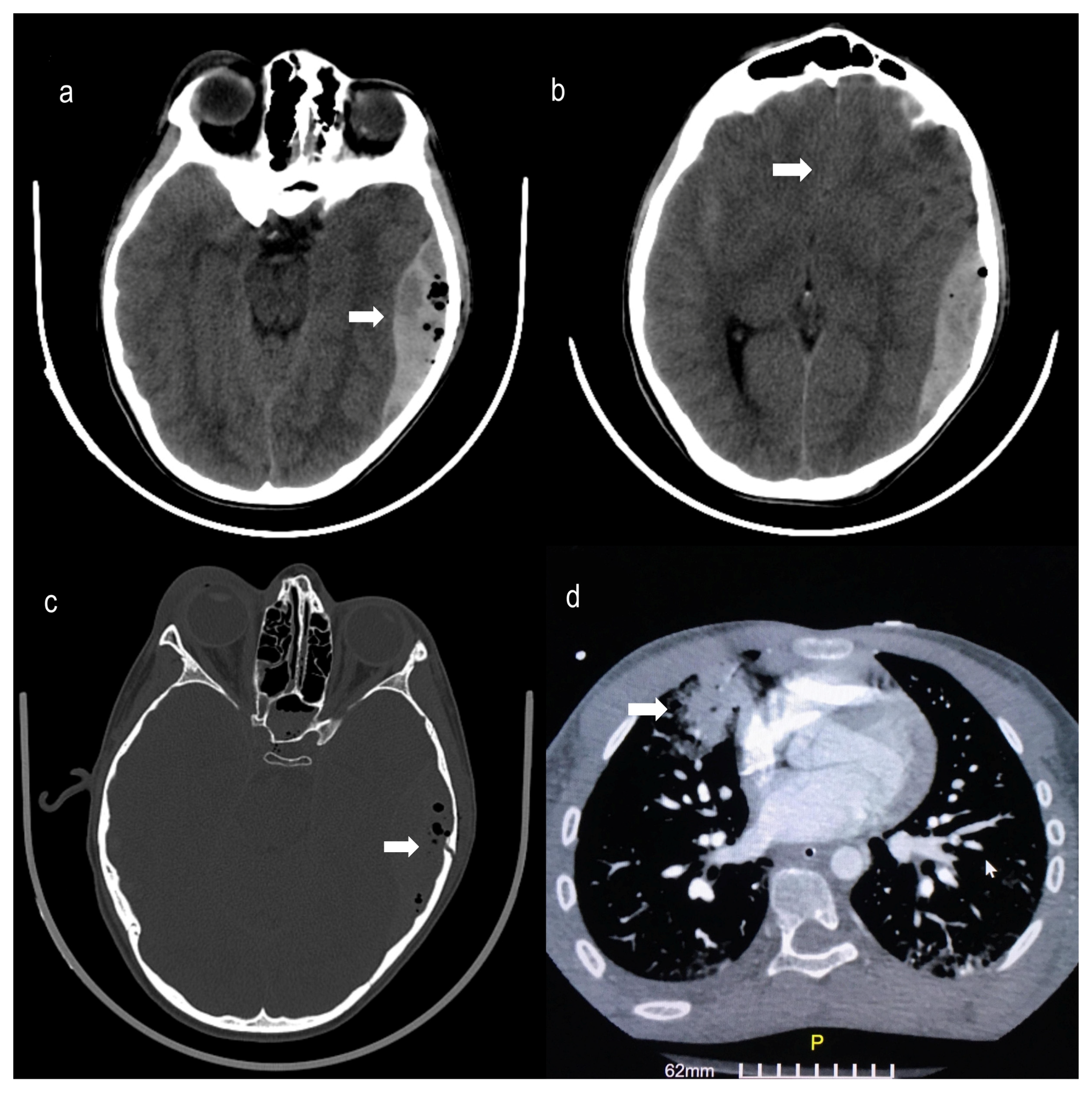

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wetzel, R.C.; Burns, R.C. Multiple trauma in children: Critical care overview. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 30, S468–S477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissaud, O.; Botte, A.; Cambonie, G.; Dauger, S.; dsse Saint Blanquat, L.; Durand, P.; Gournay, V.; Guillet, E.; Laux, D.; Leclerc, F.; et al. Experts’ recommendations for the management of cardiogenic shock in children. Ann. Intensive Care 2016, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sendi, P.; Martinez, P.; Chegondi, M.; Totapally, B.R. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in children. Cardiol. Young 2020, 30, 1711–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittekind, S.G.; Yanay, O.; Johnson, E.M.; Gibbons, E.F. Two pediatric cases of variant neurogenic stress cardiomyopathy after intracranial hemorrhage. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e1211–e1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, C.; Johler, S.M.; Hermann, M.; Fischer, M.; Thorsteinsdottir, J.; Schichor, C.; Haas, N.A. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a 12-year-old boy caused by acute brainstem bleeding-a case report. Transl. Pediatr. 2021, 10, 3110–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhavan, M.; Prasad, A. Proposed Mayo Clinic criteria for the diagnosis of Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy and long-term prognosis. Herz 2010, 35, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A.R.; Bossone, E.; Schneider, B.; Sechtem, U.; Citro, R.; Underwood, S.R.; Sheppard, M.N.; Figtree, G.A.; Parodi, G.; Akashi, Y.J.; et al. Current state of knowledge on Takotsubo syndrome: A Position Statement from the Taskforce on Takotsubo Syndrome of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hernandez, L.E. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: How much do we know of this syndrome in children and young adults? Cardiol. Young 2014, 24, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia, F.; Kaski, J.C.; Crea, F.; Camici, P.G. Pathophysiology of Takotsubo Syndrome. Circulation 2017, 135, 2426–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, R.M.; Schamberger, M.; Parent, J.J. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to non-accidental trauma presenting as an “unwitnessed” arrest. Cardiol. Young 2019, 29, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madias, J.E. Hypotension After a Pediatric Invasive Procedure: Beware of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy-Correspondence. Indian J. Pediatr. 2019, 86, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, E.A. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and its relevance to anesthesiology: A narrative review. Can. J. Anesth. Can. Anesth. 2016, 63, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awad, H.H.; McNeal, A.R.; Goyal, H. Reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: A comprehensive review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshanzamir, S.; Showkathali, R. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy a short review. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2013, 9, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Topal, Y.; Topal, H.; Doğan, C.; Tiryaki, S.B.; Biteker, M. Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy in childhood. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2020, 179, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, S.; Inokuchi, S.; Yamagiwa, T.; Aoki, H.; Nakagawa, Y.; Yamamoto, I. Tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction with ST-segment elevation after central spinal cord injury: A case report. J. Emerg. Med. 2010, 39, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huis In ’t Veld, M.A.; Craft, C.A.; Hood, R.E. Blunt Cardiac Trauma Review. Cardiol. Clin. 2018, 36, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonas, K.S.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Texakalidis, P.; Hemmati, P.; Schizas, D.; Economopoulos, K.P. Pediatric Cardiac Trauma in the United States: A Systematic Review. World J. Pediatr. Congenit. Heart Surg. 2018, 9, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangha, G.S.; Pepelassis, D.; Buffo-Sequeira, I.; Seabrook, J.A.; Fraser, D.D. Serum troponin-I as an indicator of clinically significant myocardial injury in paediatric trauma patients. Injury 2012, 43, 2046–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, B.; Solh, T. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: Review of broken heart syndrome. JAAPA 2020, 33, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.; Rzechorzek, W.; Herzog, E.; Lüscher, T.F. Misconceptions and Facts About Takotsubo Syndrome. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, K.X.; Ng, B.H.Z.; Chua, M.H.X. A unique case of acute brain haemorrhage with left ventricular systolic failure requiring ECMO. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- El-Battrawy, I.; Borggrefe, M.; Akin, I. Takotsubo Syndrome and Embolic Events. Heart Fail. Clin. 2016, 12, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, K.J.; Cammann, V.L.; Szawan, K.A.; Stähli, B.E.; Wischnewsky, M.; Di Vece, D.; Citro, R.; Jaguszewski, M.; Seifert, B.; Sarcon, A.; et al. Intraventricular Thrombus Formation and Embolism in Takotsubo Syndrome: Insights From the International Takotsubo Registry. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Miron, J.L.; Dillon, P.A.; Saini, A.; Balzer, D.T.; Singh, J.; Kolovos, N.S.; Duncan, J.G.; Keller, M.S. Left main coronary artery dissection in pediatric sport-related chest trauma. J. Emerg. Med. 2014, 47, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsitsipanis, C.; Miliaraki, M.; Michailou, M.; Geromarkaki, E.; Spanaki, A.-M.; Nyktari, V.; Yannopoulos, A.; Moustakis, N.; Ilia, S. Severe and Atypical Presentation of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy in a Pediatric Patient after a Serious Crash Injury—Case Report and Literature Review. Pediatr. Rep. 2023, 15, 396-402. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric15030036

Tsitsipanis C, Miliaraki M, Michailou M, Geromarkaki E, Spanaki A-M, Nyktari V, Yannopoulos A, Moustakis N, Ilia S. Severe and Atypical Presentation of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy in a Pediatric Patient after a Serious Crash Injury—Case Report and Literature Review. Pediatric Reports. 2023; 15(3):396-402. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric15030036

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsitsipanis, Christos, Marianna Miliaraki, Maria Michailou, Elisavet Geromarkaki, Anna-Maria Spanaki, Vasilia Nyktari, Andreas Yannopoulos, Nikolaos Moustakis, and Stavroula Ilia. 2023. "Severe and Atypical Presentation of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy in a Pediatric Patient after a Serious Crash Injury—Case Report and Literature Review" Pediatric Reports 15, no. 3: 396-402. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric15030036

APA StyleTsitsipanis, C., Miliaraki, M., Michailou, M., Geromarkaki, E., Spanaki, A.-M., Nyktari, V., Yannopoulos, A., Moustakis, N., & Ilia, S. (2023). Severe and Atypical Presentation of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy in a Pediatric Patient after a Serious Crash Injury—Case Report and Literature Review. Pediatric Reports, 15(3), 396-402. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric15030036