AUDISTIM® Day/Night Alleviates Tinnitus-Related Handicap in Patients with Chronic Tinnitus: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

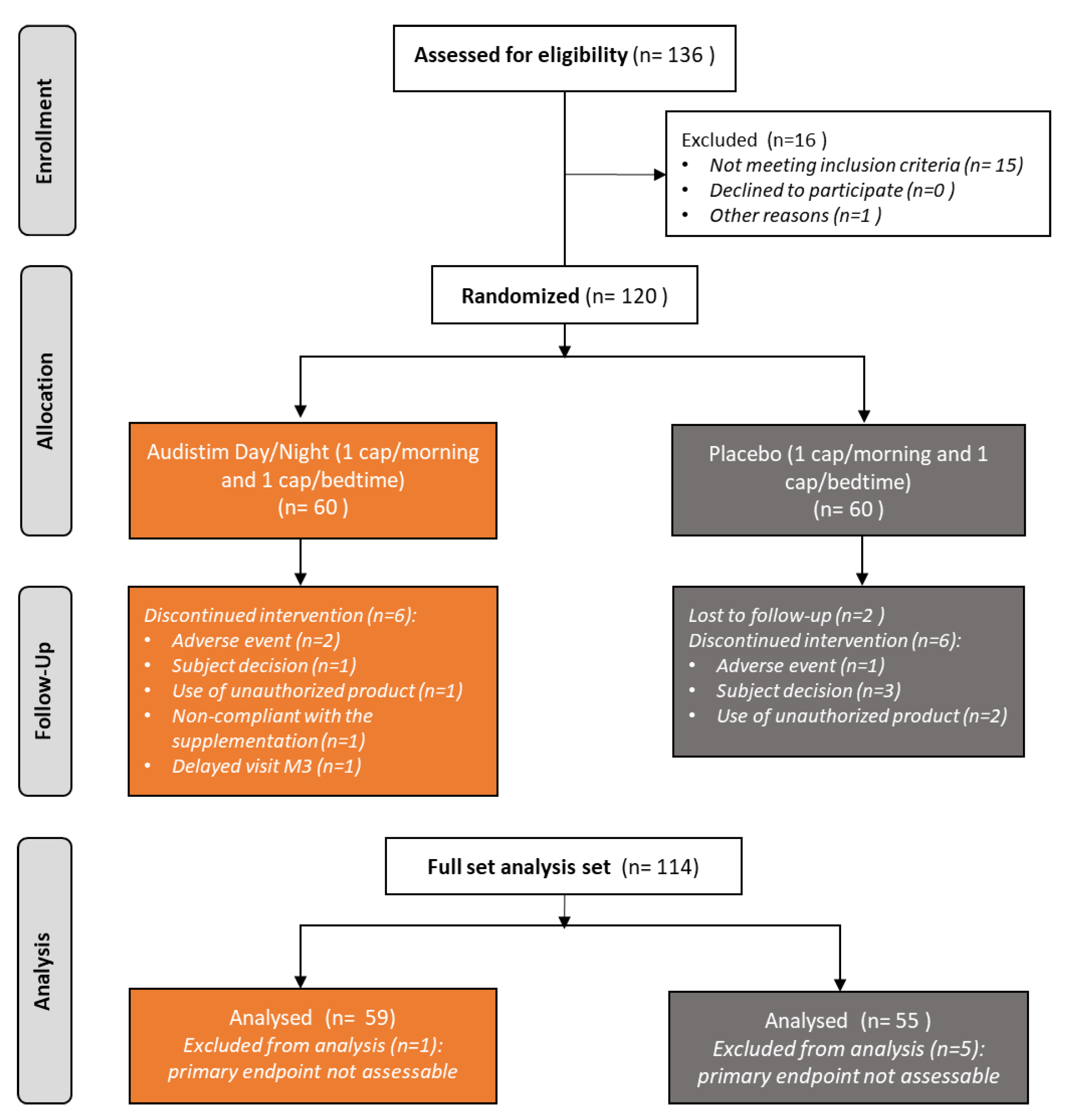

3.1. Patient Disposition

3.2. Description of Patients and Tinnitus at Baseline

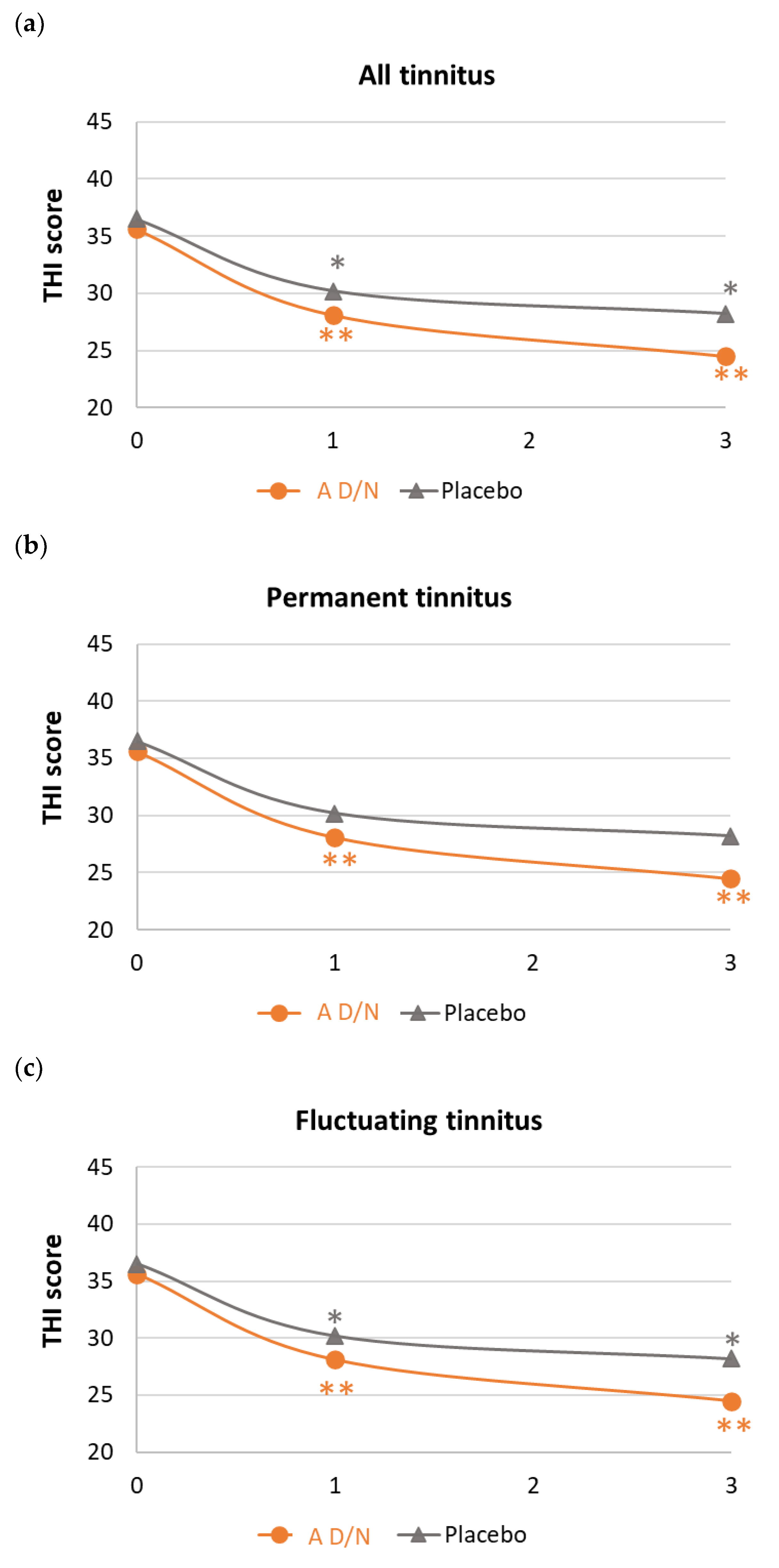

3.3. Changes in Tinnitus-Related Handicap under Dietary Supplementation

3.4. Psychological Stress, Sleep Quality and Subjective Assessment of Tinnitus Improvement

3.4.1. Psychological Stress and Sleep Quality

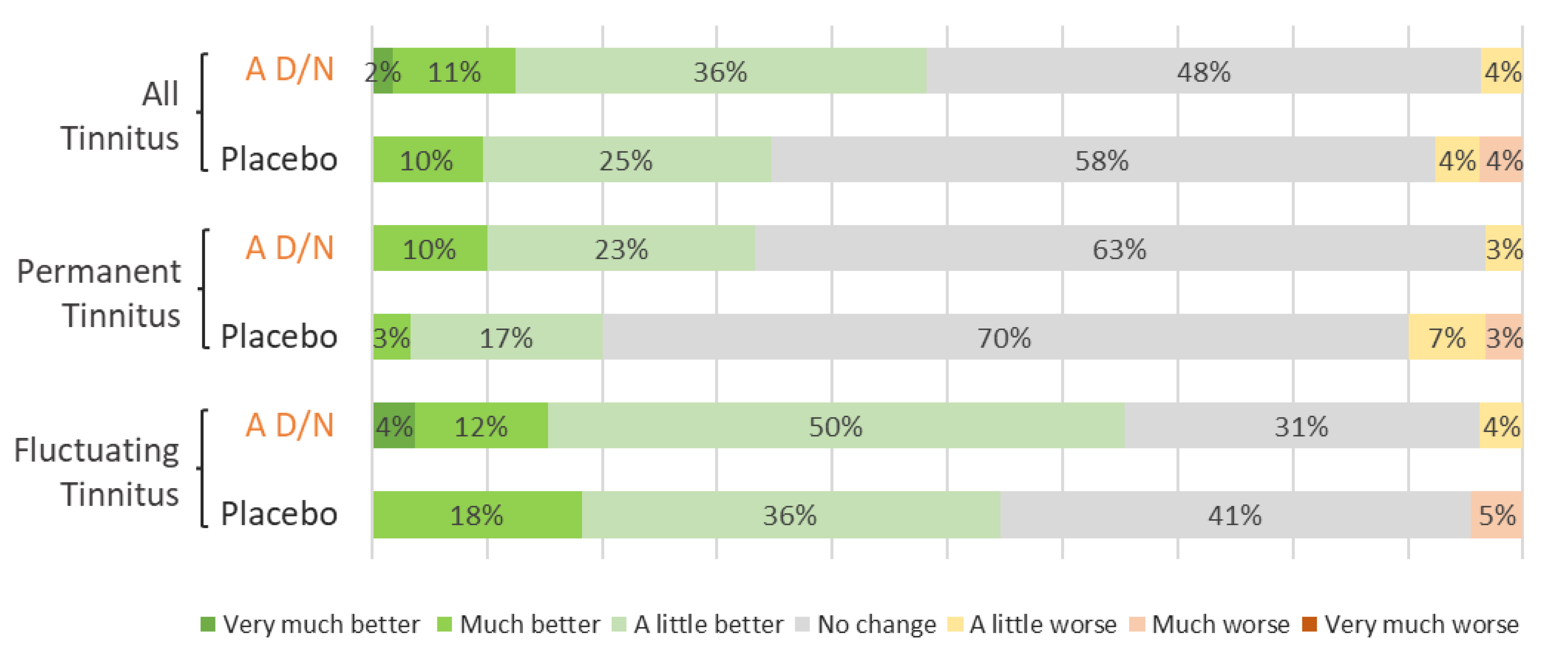

3.4.2. Subjective Assessment

3.5. Safety

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ICD11, Tinnitus. 2019. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse/2024-01/mms/en#1089305710 (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- McFadden, D. Tinnitus: Facts, Theories, and Treatments; National Academy of Sciences Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Baguley, D.; McFerran, D.; Hall, D. Tinnitus. Lancet 2013, 382, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langguth, B.; Kreuzer, P.M.; Kleinjung, T.; De Ridder, D. Tinnitus: Causes and clinical management. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, D.; Schlee, W.; Vanneste, S.; Londero, A.; Weisz, N.; Kleinjung, T.; Shekhawat, G.S.; Elgoyhen, A.B.; Song, J.J.; Andersson, G.; et al. Tinnitus and tinnitus disorder: Theoretical and operational definitions (an international multidisciplinary proposal). Prog. Brain Res. 2021, 260, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarach, C.M.; Lugo, A.; Scala, M.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Cederroth, C.R.; Odone, A.; Garavello, W.; Schlee, W.; Langguth, B.; Gallus, S. Global Prevalence and Incidence of Tinnitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.; Lugo, A.; Akeroyd, M.A.; Schlee, W.; Gallus, S.; Hall, D.A. Tinnitus prevalence in Europe: A multi-country cross-sectional population study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 12, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunkel, D.E.; Bauer, C.A.; Sun, G.H.; Rosenfeld, R.M.; Chandrasekhar, S.S.; Cunningham, E.R., Jr.; Archer, S.M.; Blakley, B.W.; Carter, J.M.; Granieri, E.C.; et al. Clinical practice guideline: Tinnitus. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2014, 151 (Suppl. S2), S1–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, C.A. Tinnitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, J.A.; Reavis, K.M.; Griest, S.E.; Thielman, E.J.; Theodoroff, S.M.; Grush, L.D.; Carlson, K.F. Tinnitus: An Epidemiologic Perspective. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 53, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méric, C.; Gartner, M.; Collet, L.; Chéry-Croze, S. Psychopathological Profile of Tinnitus Sufferers: Evidence Concerning the Relationship between Tinnitus Features and Impact on Life. Audiol. Neurotol. 1998, 3, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinnitus Retraining Therapy Trial Research Group; Scherer, R.W.; Formby, C. Effect of Tinnitus Retraining Therapy vs Standard of Care on Tinnitus-Related Quality of Life: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2019, 145, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meikle, M.; Taylor-Walsh, E. Characteristics of tinnitus and related observations in over 1800 tinnitus clinic patients. J. Laryngol. Otol. Suppl. 1984, 9, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reavis, K.M.; Henry, J.A.; Marshall, L.M.; Carlson, K.F. Prevalence of self-reported depression symptoms and perceived anxiety among community-dwelling U.S. adults reporting tinnitus. Perspect. ASHA Spec. Interest Groups 2020, 5, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langguth, B.; Elgoyhen, A.B.; Cederroth, C.R. Therapeutic Approaches to the Treatment of Tinnitus. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2019, 59, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.J.; Chen, Y.W.; Zeng, B.Y.; Hung, C.M.; Zeng, B.S.; Stubbs, B.; Carvalho, A.F.; Thompson, T.; Roerecke, M.; Su, K.P.; et al. Efficacy of pharmacologic treatment in tinnitus patients without specific or treatable origin: A network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 39, 101080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langguth, B.; Kleinjung, T.; Schlee, W.; Vanneste, S.; De Ridder, D. Tinnitus Guidelines and Their Evidence Base. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Person, O.C.; Junior, F.V.; Altoé, J.; Portes, L.M.; Lopes, P.R.; dos Santos Puga, M.E. O que revisões sistemáticas Cochrane dizem sobre terapêutica para zumbido? ABCS Health Sci. 2022, 47, e022301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridou, A.I.; Zagora, E.T.; Petridis, P.; Korres, G.S.; Gazouli, M.; Xenelis, I.; Kyrodimos, E.; Kontothanasi, G.; Kaliora, A.C. The Effect of Antioxidant Supplementation in Patients with Tinnitus and Normal Hearing or Hearing Loss: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frachet, B.; Portmann, D.; Allaert, F. Observational Study to assess the effect of Audistim® on the quality of life of patients presenting with chronic tinnitus. Rev. De Laryngol. -Otol. -Rhinol. 2017, 138, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Van Becelaere, T.; Zahti, H.; Polet, T.; Glorieux, P.; Portmann, D.; Rigaudier, F.; Herpin, F.; Decat, M. Improving quality of life in subjective tinnitus patients with Audistim®. Rev. Laryngol. Otol. Rhinol. 2019, 140, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, C.W.; Sandridge, S.A.; Jacobson, G.P. Psychometric adequacy of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) for evaluating treatment outcome. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 1998, 9, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kikidis, D.; Vassou, E.; Schlee, W.; Iliadou, E.; Markatos, N.; Triantafyllou, A.; Langguth, B. Methodological Aspects of Randomized Controlled Trials for Tinnitus: A Systematic Review and How a Decision Support System Could Overcome Barriers. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghulyan-Bédikian, V.; Paolino, M.; Giorgetti-D’Esclercs, F.; Paolino, F. Psychometric properties of a French adaptation of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Encephale 2010, 36, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Les Références Nutritionnelles en Vitamines et Minéraux. Available online: https://www.anses.fr/fr/content/les-r%C3%A9f%C3%A9rences-nutritionnelles-en-vitamines-et-min%C3%A9raux (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Zeman, F.; Koller, M.; Figueiredo, R.; Aazevedo, A.; Rates, M.; Coelho, C.; Kleinjung, T.; De Ridder, D.; Langguth, B.; Landgrebe, M. Tinnitus handicap inventory for evaluating treatment effects: Which changes are clinically relevant? Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2011, 145, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemyre, L.; Tessier, R. La mesure de stress psychologique en recherche de première lgne: Concept, modèle et mesure. Can. Fam. Psysician–Le Médecin De Fam. Can. 2003, 49, 1166–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). In ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials E9; European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 1998; Available online: https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/E9_Guideline.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Cohen, J. Things I have learned (so far). Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.S.; Tucci, D.L.; Merson, M.H.; O’Donoghue, G.M. Global hearing health care: New findings and perspectives. Lancet 2017, 390, 2503–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppitz, S.J.; Garcia, M.V.; Bruno, R.S.; Zemolin, C.M.; Baptista, B.O.; Turra, B.O.; Barbisan, F.; Cruz, I.B.; Silveira, A.F. Supplementation with açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Martius) for the treatment of chronic tinnitus: Effects on perception, anxiety levels and oxidative metabolism biomarkers. Codas 2022, 34, e20210076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sereda, M.; Xia, J.; Scutt, P.; Hilton, M.P.; El Refaie, A.; Hoare, D.J. Ginkgo biloba for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, CD013514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, A.; Kamrava, S.K.; Moore, B.C.; Reiter, R.J.; Ghaznavi, H.; Kamali, M.; Mehrzadi, S. Molecular Aspects of Melatonin Treatment in Tinnitus: A Review. Curr. Drug Targets 2019, 20, 1112–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Mayo, J.C.; Tan, D.X.; Sainz, R.M.; Alatorre-Jimenez, M.; Qin, L. Melatonin as an antioxidant: Under promises but over delivers. J. Pineal Res. 2016, 61, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EMA/HMPC/196745/2012; Community Herbal Monograph on Melissa officinalis L. folium. European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013.

- Landgrebe, M.; Azevedo, A.; Baguley, D.; Bauer, C.; Cacace, A.; Coelho, C.; Dornhoffer, J.; Figueiredo, R.; Flor, H.; Hajak, G.; et al. Methodological aspects of clinical trials in tinnitus: A proposal for an international standard. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012, 73, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousema, E.J.; Koops, E.A.; van Dijk, P.; Dijkstra, P.U. Association between subjective tinnitus and cervical spine or temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review. Trends Hear. 2018, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| A D/N (n = 59) | Placebo (n = 55) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 54.6 (12.5) | 52.9 (10.1) | 0.4281 * |

| Median (IQR) | 59.0 (43.0 65.0) | 53.0 (44.0; 59.0) | |

| Gender (% male/% female) | 37.3/62.7 | 47.3/52.7 | 0.2806 ** |

| Concomitant disorder (Yes) (n (%)) | 23 (39.0) | 13 (23.6) | 0.1693 ** |

| Clinical abnormalities (Yes) (n (%)) | 1 (1.7) | 5 (9.1) | 0.1047 ** |

| A D/N (n = 59) | Placebo (n = 55) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 9.5 (9.7) | 9.0 (9.3) | 0.7862 * |

| Median (IQR) | 6.0 (3.0; 13.0) | 5.0 (2.0; 15.0) | |

| Main etiology | |||

| Idiopathic (n (%)) | 25/42.4 | 18/32.7 | 0.7529 ** |

| Acoustic trauma (n (%)) | 18/30.5 | 20/36.4 | 0.5075 ** |

| ENT/Viral infection (n (%)) | 6/10.2 | 6/10.9 | 0.7529 ** |

| Presbycusis (n (%)) | 5/8.5 | 2/3.6 | 0.4404 ** |

| Vascular disorders (n (%)) | 2/3.4 | 5/9.1 | 0.2597 ** |

| Location | |||

| Both ears (n (%)) | 37/62.7 | 38/69.1 | |

| Right or Left ear (n (%)) | 19/32.2 | 17/30.9 | 0.2105 ** |

| Head (n (%)) | 3/5.1 | 0/0.0 | |

| Tinnitus onset | |||

| Permanent (n (%)) | 32/54.2 | 31/56.4 | 0.8195 ** |

| Fluctuating (n (%)) | 27/45.8 | 24/43.6 | |

| Associated symptoms (Yes) (n (%)) | 41/69.5 | 36/65.5 | |

| Hypoacusis/hyperacusis | 25/42.4 | 25/45.5 | 0.8885 ** |

| Headache | 13/22.0 | 8/14.5 | 0.3027 ** |

| Annoyance (0–10 VAS) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5.3 (1.5) | 4.9 (1.8) | 0.1913 * |

| Median (IQR) | 5.0 (4.0; 6.7) | 5.0 (3.0; 7.0) | |

| THI total score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 38.9 (16.2) | 35.7 (17.5) | 0.3180 * |

| Median (IQR) | 36.0 (26.0; 54.0) | 30.0 (22.0; 48.0) | |

| Tinnitus classification | |||

| No handicap (n (%)) | 7 (11.9) | 7 (12.7) | 0.6329 ** |

| Mild handicap (n (%)) | 23 (39.0) | 23 (41.8) | |

| Moderate handicap (n (%)) | 23 (39.0) | 16 (29.1) | |

| Severe handicap (n (%)) | 6 (10.2) | 9 (16.4) | |

| Catastrophic handicap (n (%)) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| A D/N | Placebo | p-Value | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All tinnitus (n = 104) | (n = 59) | (n = 55) | ||

| Changes in THI scores | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −13.2 (16.0) | −6.2 (14.4) | 0.0158 * | 0.44 |

| 95%CI | −17.4/−9.1 | −10.1/−2.3 | ||

| THI score reduction ≥20% | ||||

| n (%) | 40 (67.8) | 26 (47.3) | 0.0266 ** | |

| Permanent tinnitus (n = 63) | (n = 32) | (n = 31) | ||

| Changes in THI scores | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −15.0 (16.3) | −4.6 (12.8) | 0.0065 * | 0.71 |

| 95%CI | −20.9/−9.1 | −9.3/0.1 | ||

| THI score reduction ≥20% | ||||

| n (%) | 23 (71.9) | 15 (48.4) | 0.0568 ** | |

| Fluctuating tinnitus (n = 51) | (n = 27) | (n = 24) | ||

| Changes in THI scores | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −11.1 (15.7) | −8.3 (16.3) | 0.5384 * | 0.17 |

| 95%CI | −17.3/−4.9 | −15.2/−1.5 | ||

| THI score reduction ≥20% | ||||

| n (%) | 17 (63.0) | 11 (45.8) | 0.2198 ** |

| A D/N | Placebo | A D/N vs. Placebo | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Mean (SD) | Final Mean (SD) | p-Value * | Baseline Mean (SD) | Final Mean (SD) | p-Value * | p-Value ** | Cohen’s d | |

| All tinnitus | (n = 56) | (n = 52) | ||||||

| MSP-9 scores | 35.4 (12.6) | 31.4 (11.2) | 0.008 | 34.1 (11.2) | 32.2 (11.1) | 0.1947 | 0.3190 | 0.19 |

| PSQI scores | 7.4 (3.5) | 6.0 (3.2) | 0.0014 | 7.3 (3.5) | 6.3 (3.0) | 0.0374 | 0.3979 | 0.16 |

| Permanent tinnitus | (n = 30) | (n = 30) | ||||||

| MSP-9 scores | 33.5 (10.4) | 29.4 (9.8) | 0.0655 | 32.5 (10.8) | 31.8 (11.1) | 0.6561 | 0.2062 | 0.33 |

| PSQI scores | 6.7 (3.6) | 5.3 (2.5) | 0.0154 | 6.4 (3.4) | 6.0 (3.4) | 0.4077 | 0.1855 | 0.33 |

| Fluctuating tinnitus | (n = 26) | (n = 22) | ||||||

| MSP-9 scores | 37.5 (14.5) | 33.7 (12.4) | 0.0586 | 36.1 (11.5) | 32.6 (11.4) | 0.2026 | 0.9359 | 0.03 |

| PSQI scores | 8.2 (3.3) | 6.7 (3.8) | 0.0385 | 8.4 (3.3) | 6.8 (2.3) | 0.0458 | 0.9128 | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Portmann, D.; Esteve-Fraysse, M.J.; Frachet, B.; Herpin, F.; Rigaudier, F.; Juhel, C. AUDISTIM® Day/Night Alleviates Tinnitus-Related Handicap in Patients with Chronic Tinnitus: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Audiol. Res. 2024, 14, 359-371. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres14020031

Portmann D, Esteve-Fraysse MJ, Frachet B, Herpin F, Rigaudier F, Juhel C. AUDISTIM® Day/Night Alleviates Tinnitus-Related Handicap in Patients with Chronic Tinnitus: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Audiology Research. 2024; 14(2):359-371. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres14020031

Chicago/Turabian StylePortmann, Didier, Marie José Esteve-Fraysse, Bruno Frachet, Florent Herpin, Florian Rigaudier, and Christine Juhel. 2024. "AUDISTIM® Day/Night Alleviates Tinnitus-Related Handicap in Patients with Chronic Tinnitus: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial" Audiology Research 14, no. 2: 359-371. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres14020031

APA StylePortmann, D., Esteve-Fraysse, M. J., Frachet, B., Herpin, F., Rigaudier, F., & Juhel, C. (2024). AUDISTIM® Day/Night Alleviates Tinnitus-Related Handicap in Patients with Chronic Tinnitus: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Audiology Research, 14(2), 359-371. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres14020031