The Experiences of Family Members of Patients Discharged from Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

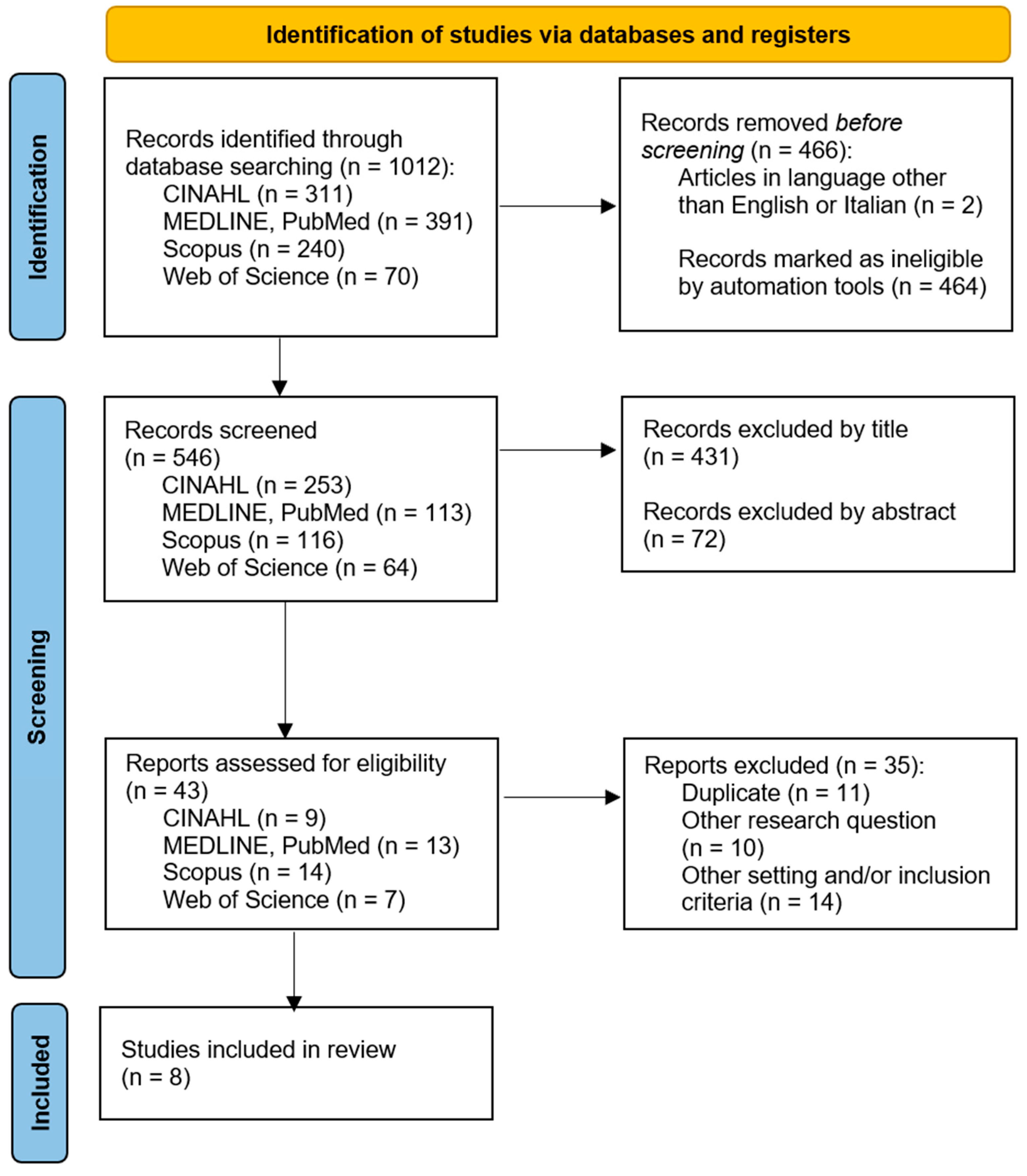

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Criteria for Inclusion

2.4. Quality Appraisal

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Characteristics of Included Studies

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Grappling with a Weighty Burden

3.2. Theme 2: Recognizing and Confronting Adversities along the Way

3.3. Theme 3: Seeking Support beyond One’s Own Resources

3.4. Theme 4: Addressing Comprehensive Care Requirements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beesley, S.J.; Hopkins, R.O.; Holt-Lunstad, J.; Wilson, E.L.; Butler, J.; Kuttler, K.G.; Orme, J.; Brown, S.M.; Hirshberg, E.L. Acute Physiologic Stress and Subsequent Anxiety Among Family Members of ICU Patients. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, P.; Thomson, P.; Shepherd, A. Families of patients in ICU: A Scoping review of their needs and satisfaction with care. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Beer, J.; Brysiewicz, P. Developing a theory of family care during critical illness. S. Afr. Med. J. 2019, 35, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, B.; Moroney, T. Involving relatives in ICU patient care: Critical care nursing challenges. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needham, D.M.; Davidson, J.; Cohen, H.; Hopkins, R.O.; Weinert, C.; Wunsch, H.; Zawistowski, C.; Bemis-Dougherty, A.; Berney, S.C.; Bienvenu, O.J.; et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: Report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, J.E.; Jones, C.; Bienvenu, O.J. Family response to critical illness: Postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, P.; Kheir, Y.N.P.; Wang, S.; Khan, S.; Scheunemann, L.; Khan, B. Aging and Postintensive Care Syndrome-Family: A Critical Need for Geriatric Psychiatry. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kean, S.; Donaghy, E.; Bancroft, A.; Clegg, G.; Rodgers, S. Theorising survivorship after intensive care: A systematic review of patient and family experiences. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 2584–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobato, C.T.; Camoes, J.; Carvalho, D.; Vales, C.; Dias, C.C.; Gomes, E.; Araújo, R. Risk factors associated with post-intensive care syndrome in family members (PICS-F): A prospective observational study. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2023, 24, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielis, M.; Terzoni, S.; Buttolo, T.; Costantini, C.; Piani, T.; Zanardo, D.; Palese, A.; Destrebecq, A.L.L. Experience of relatives in the first three months after a non-COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit discharge: A qualitative study. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, A.; Schweickert, W.D.; Files, D.C.; Bakhru, R.N. A Survey to Assess Primary Care Physician Awareness of Complications Following Critical Illness. J. Intensive Care Med. 2023, 38, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Tufanaru, C.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Mu, P.F. Conducting systematic reviews of association (etiology): The Joanna Briggs Institute’s approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklists. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Mattiussi, E.; Danielis, M.; Venuti, L.; Vidoni, M.; Palese, A. Sleep deprivation determinants as perceived by intensive care unit patients: Findings from a systematic review, meta-summary and meta-synthesis. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2019, 53, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ågård, A.S.; Egerod, I.; Tonnesen, E.; Lomborg, K. From spouse to caregiver and back: A grounded theory study of post-intensive care unit spousal caregiving. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 1892–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwonka, A.I.; Herridge, M.S.; Chan, L.; Chu, L.M.; Matte, A.; Cameron, J.I. Changing support needs of survivors of complex critical illness and their family caregivers across the care continuum: A qualitative pilot study of towards RECOVER. J. Crit. Care 2015, 30, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frivold, G.; Slettebo, A.; Dale, B. Family members’ lived experiences of everyday life after intensive care treatment of a loved one: A phenomenological hermeneutical study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lingler, J.H.; Donahoe, M.P.; Happ, M.B.; Hoffman, L.A.; Tate, J.A. Home discharge following critical illness: A qualitative analysis of family caregiver experience. Heart Lung 2018, 47, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelderup, M.; Samuelson, K. Experiences of partners of intensive care survivors and their need for support after intensive care. Nurs. Crit. Care 2020, 25, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sleeuwen, D.; van de Laar, F.; Geense, W.; van den Boogaard, M.; Zegers, M. Health problems among family caregivers of former intensive care unit (ICU) patients: An interview study. BJGP Open 2020, 4, bjgpopen20X101061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vester, L.B.; Holm, A.; Dreyer, P. Patients’ and relatives’ experiences of post-ICU everyday life: A qualitative study. Nurs. Crit. Care 2022, 27, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullman, A.J.; Aitken, L.M.; Rattray, J.; Kenardy, J.; Le Brocque, R.; MacGillivray, S.; Hull, A.M. Intensive care diaries to promote recovery for patients and families after critical illness: A Cochrane Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattray, J. Life after critical illness: An overview. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappellini, E.; Bambi, S.; Lucchini, A.; Milanesio, E. Open intensive care units: A global challenge for patients, relatives, and critical care teams. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2014, 33, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.E.; Aslakson, R.A.; Long, A.C.; Puntillo, K.A.; Kross, E.K.; Hart, J.; Cox, C.E.; Wunsch, H.; Wickline, M.A.; Nunnally, M.E.; et al. Guidelines for Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Beusekom, I.; Bakhshi-Raiez, F.; de Keizer, N.F.; Dongelmans, D.A.; van der Schaaf, M. Reported burden on informal caregivers of ICU survivors: A literature review. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexhaj, S.; Nguyen, A.; Favrod, J.; Coloni-Terrapon, C.; Buisson, L.; Drainville, A.L.; Martinez, D. Women involvement in the informal caregiving field: A perspective review. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1113587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ågård et al., 2015 [17] | Czerwonka et al., 2015 [18] | Frivold et al., 2016 [19] | Choi et al., 2018 [20] | Nelderup et al., 2020 [21] | Van Sleeuwen et al., 2020 [22] | Danielis et al., 2022 [10] | Vester et al., 2022 [23] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section A | ||||||||

| Q1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Q2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Q3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Q4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to meet the aims of the research? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Q5. Was the data collected in away that addressed the research issue? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Q6. Was the relationship between researcher and participants adequately considered? | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Section B | ||||||||

| Q7. Were ethical issues taken in consideration? | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Q8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Q9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Section C | ||||||||

| Q10. How valuable is the research? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Total Score | 10 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 9 |

| Title, Authors, Publication Year | Design | Setting and Country | Aim (s) | Data Collection Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From spouse to caregiver and back: a grounded theory study of post-intensive care unit spousal caregiving Agard et al., 2015 [17] | Qualitative study based on the Grounded Theory methodology | General and Neurosurgical ICU, Denmark | To explore the challenges facing spouses of ICU survivors; to describe and explain their concerns and caregiving strategies during the first 12 months post-ICU discharge | Semi- structured interviews | Spouses have a crucial and multifaceted role in the recovery process after leaving the ICU; they have lived through the transition of their role from spouse to caregiver and back. Hospital staff, rehabilitation specialists, and primary care providers should recognize the significant contribution of spouses |

| Changing support needs of survivors of complex critical illness and their family caregivers across the care continuum: A qualitative pilot study of Towards RECOVER Czerwonka et al., 2015 [18] | Qualitative study using the Timing It Right framework | University-affiliated medical-surgical ICUs, Canada | To explore participants’ experiences and needs for information, emotional support, and training at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after intensive care unit (ICU) discharge | Semi- structured interviews | Interventions targeting improved family outcomes after critical illness should consider the changing support requirements of both survivors and caregivers as they progress through the illness and recovery process. Early intervention and transparent communication regarding care transitions and recovery can help alleviate uncertainties for all involved. Ongoing family-centered follow-up programs have the potential to assist caregivers in managing their perceived caregiving duties |

| Family members’ lived experiences of everyday life after intensive care treatment of a loved one: a phenomenological hermeneutical study Frivold et al., 2016 [19] | Phenomenological hermeneutical method inspired by Lindseth and Norberg | General and Medical ICU, Norway | To illuminate relatives’ experiences of everyday life after a loved one’s stay in an intensive care unit (ICU) | Semi- structured interviews. | Nursing education could prioritize the importance of communication and personalized support, aiding family members in coping during the patient’s hospitalization and fostering a sense of resilience upon returning home. After coming back home, it is crucial for family members to retain self-control and adjust to these changes for future readiness. They manage by tapping into their personal resources and relying on support from others. Additionally, some may require additional follow-up from the intensive care unit staff |

| Home discharge following critical illness: A qualitative analysis of family caregiver experience Choi et al., 2018 [20] | Descriptive qualitative study with a content analysis | General ICU, USA (Pittsburgh) | To describe the varying challenges and needs of family caregivers of ICU survivors related to patients’ home discharge | Semi- structured interviews. | Family caregivers of ICU survivors require knowledge and expertise to assist in managing patients’ care requirements, aligning expectations with the actual progress of patients, and addressing the health needs of caregivers themselves. |

| Health problems among family caregivers of former intensive care unit (ICU) patients: an interview study Van Sleeuwen et al., 2020 [22] | Exploratory qualitative study according to Braun and Clarke’s six- phases | General ICU, Netherlands | To explore health problems in family caregivers of former ICU patients and the consequences in their daily lives | Semi- structured interviews. | Caregivers continue to face various health issues, persisting long after their loved ones are discharged from the ICU. It is crucial for healthcare providers to prioritize the health of not just ICU patients but also their caregivers. Identifying and addressing caregivers’ health concerns at an earlier stage is essential to providing them with the necessary care and support |

| Experiences of partners of intensive care survivors and their need for support after intensive care Nelderup et al., 2020 [21] | Qualitative descriptive study with a content analysis | General ICU, Sweden | To explore the experiences of partners of intensive care survivors and their need for support after ICU | Semi- structured interviews. | Partners require comprehensive and ongoing support from healthcare professionals and others throughout and after post-intensive care periods. While intensive care can often engender feelings of chaos for partners, strengthening family relationships and providing appropriate comforting support can mitigate this chaos and pave the way for a smoother recovery journey, fostering a more positive outlook on the future |

| Patients’ and relatives’ experiences of post-ICU everyday life: A qualitative study Vester et al., 2022 [23] | Qualitative study within the phenomenological-hermeneutic tradition | Multidisciplinary ICU, Denmark | To explore patients’ and relatives’ experiences of everyday life after critical illness | Semi- structured interviews. | The research highlights the significance of broadening the recognized aspects of PICS to encompass a social dimension, facilitating family-centered care within and outside the ICU. Additionally, it underscores the importance of developing tailored rehabilitation approaches to address the diverse health needs of both patients and their relatives |

| Experience of relatives in the first three months after a non-COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit discharge: a qualitative study Danielis et al., 2022 [10] | Descriptive qualitative study with a thematic analysis | General ICU, Italy | To explore and describe the experiences of a relative who has been facing day-to-day life during the first three months after a non-COVID-19 ICU discharge | Semi- structured interviews. | Upon discharge, family members confronted constraints in community services, compelling them to seek supplementary assistance from private healthcare providers. Moreover, changes in the patient’s treatment plan intensified specific caregiving challenges, resulting in a sense of isolation. Relatives encountered a twofold limitation in opportunities, both within the hospital, with restricted involvement and limited access to ICU accessibility, and at home, concerning formal and informal care alternatives |

| Gender | Relationship Degree | Length of Stay in ICU Days Range (Mean) | Timing of Follow-Up Interview Months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | ||||

| Ågård et al., 2015 [17] | 7 | 11 | 11 wives, 7 husbands | 5–74 | 3–12 |

| Czerwonka et al., 2015 [18] | 1 | 6 | U | 10–64 (29) | 3–6–12–24 |

| Frivold et al., 2016 [19] | 6 | 7 | 1 son, 6 wives, 3 husbands, 1 brother, 1 mother, and 1 grandson | 2–42 | 3–13 |

| Choi et al., 2018 [20] | 4 | 16 | 13 spouses or significant other, 3 adult child, and 4 parents or siblings | 5–39 (23) | 0.5–2–4 |

| Van Sleeuwen et al., 2020 [22] | 3 | 10 | U | >5 (4.5) | 3–36 |

| Nelderup et al., 2020 [21] | 2 | 4 | 4 wives, 2 husbands | 10–69 | 6–10 |

| Vester et al., 2022 [23] | 1 | 6 | 4 wives, 2 mothers and 1 husband | 1–14 | U |

| Danielis et al., 2022 [10] | 3 | 11 | 7 partner, 3 daughter/son, 2 mother/father, 1 sister/brother, and 1 other degree of relatedness | (18) | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Basso, B.; Fogolin, S.; Danielis, M.; Mattiussi, E. The Experiences of Family Members of Patients Discharged from Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 1504-1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020113

Basso B, Fogolin S, Danielis M, Mattiussi E. The Experiences of Family Members of Patients Discharged from Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(2):1504-1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020113

Chicago/Turabian StyleBasso, Benedetta, Sebastiano Fogolin, Matteo Danielis, and Elisa Mattiussi. 2024. "The Experiences of Family Members of Patients Discharged from Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies" Nursing Reports 14, no. 2: 1504-1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020113

APA StyleBasso, B., Fogolin, S., Danielis, M., & Mattiussi, E. (2024). The Experiences of Family Members of Patients Discharged from Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Nursing Reports, 14(2), 1504-1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020113