Interventions to Relieve the Burden on Informal Caregivers of Older People with Dementia: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

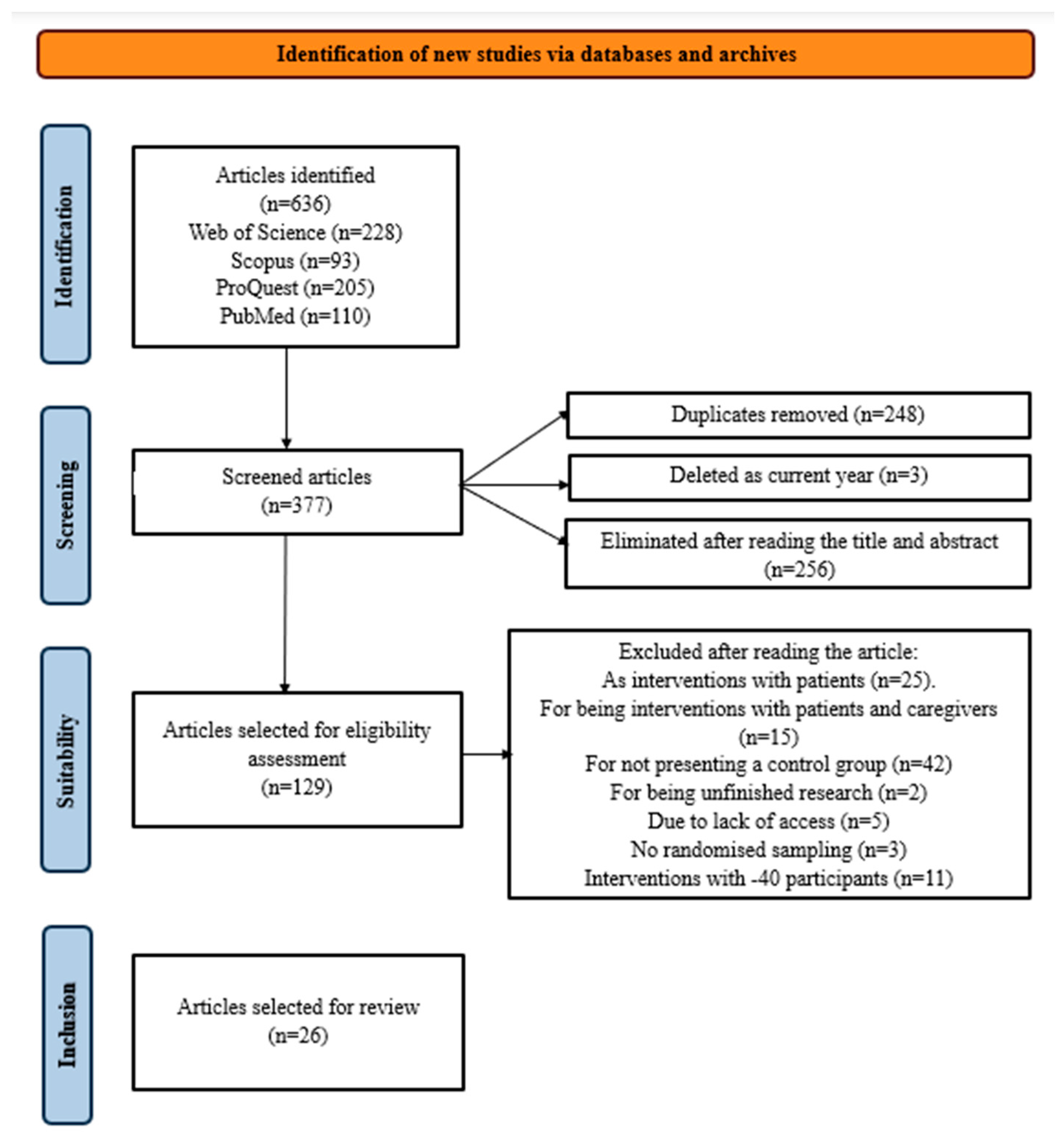

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Coding and Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Design

3.2. Sample Characteristics

3.3. Type of Intervention

3.4. Duration and Follow-Up

3.5. Study Variables and Measurement Instruments

3.6. Results and Effectiveness of Interventions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Demencia 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Vetrano, D.L.; Onder, G.; Gimeno-Feliu, L.A.; Coscollar-Santaliestra, C.; Carfí, A.; Pisciotta, M.S.; Angleman, S.; Melis, R.J.F.; Santoni, G.; et al. Assessing and Measuring Chronic Multimorbidity in the Older Population: A Proposal for Its Operationalization. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 72, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Sommerlad, A.; Orgeta, V.; Costafreda, S.G.; Huntley, J.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017, 390, 2673–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Mármol, J.M.; Flores-Antigüedad, M.L.; Castro-Sánchez, A.M.; Tapia-Haro, R.M.; García-Ríos, M.C.; Aguilar-Ferrándiz, M.E. Inpatient dependency in activities of daily living predicts informal caregiver strain: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e177–e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarejo, A.; Eimil-Ortiz, M.; Llamas-Velasco, S.; Llanero-Luquec, M.; López-de Silanes de Miguel, C.; Prieto-Jurczynska, C. Informe de la Fundación Española del Cerebro sobre el impacto social de la enfermedad de Alzheimer y otros tipos de demencias. Neurología 2021, 36, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Mullan, J.T.; Semple, S.J.; Skaff, M.M. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 1990, 30, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarit, S.H.; Gaugler, J.E.; Jarrot, S.E. Useful services for families: Research findings and directions. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1999, 14, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beinart, N.; Weinman, J.; Wade, D.; Brady, R. Carga del cuidador e intervenciones psicoeducativas en la enfermedad de Alzheimer: Una revisión. Dement. Geriátricos Trastor. Cogn. Extra 2012, 2, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodaty, H.; Green, A.; Koschera, A. Metaanálisis de intervenciones psicosociales para cuidadores de personas con demencia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, L.N.; Belle, S.H.; Burgio, L.D.; Czaja, S.J.; Mahoney, D.; Gallagher-Thompson, D.; Burns, R.; Hauck, W.W.; Zhang, S.; Schulz, R.; et al. Effect of Multicomponent Interventions on Caregiver Burden and Depression: The REACH Multisite Initiative at 6-Month Follow-Up. Psychol. Aging 2003, 18, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cardoza, I.I.; Zapata-Vázquez, R.; Rivas-Acuña, V.; Quevedo-Tejero, E.C. Efectos de la terapia cognitivo-conductual en la sobrecarga del cuidador primario de adultos mayores. Horiz. Sanit. 2018, 17, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Button, K.S.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Mokrysz, C.; Nosek, B.A.; Flint, J.; Robinson, E.S.; Munafò, M.R. Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.W.; Coogle, C.L.; Wegelin, J. A pilot randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction for caregivers of family members with dementia. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe-Monti, M.; Vanacore, N.; Bartorelli, L.; Tognetti, A.; Giubilei, F. The savvy caregiver program: A probe multicenter randomized controlled pilot trial in caregivers of patients affected by Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016, 54, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavandadi, S.; Wright, E.M.; Graydon, M.M.; Oslin, D.W.; Wray, L.O. A randomized pilot trial of a telephone-based collaborative care management program for caregivers of individuals with dementia. Psychol. Serv. 2017, 14, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.J.; Martinez Kercher, V.; Jordan, E.J.; Savoy, A.; Hill, J.R.; Werner, N.; Owora, A.; Castelluccio, P.; Boustani, M.A.; Holden, R.J. Technology caregiver intervention for Alzheimer’s disease (I-CARE): Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of brain carenotes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 3836–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.T.; Fung, H.H.; Chan, W.C.; Lam, L.C. Short-term effects of a gain-focused reappraisal intervention for dementia caregivers: A double-blind cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 24, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, K.; Nocera, J.; Higgins, M.; Epps, F.; Brewster, G.; Lindauer, A.; Morhardt, D.; Shah, R.; Bonds, K.; Nash, R.; et al. Results of a randomized trial testing the efficacy of Tele-Savvy, an online synchronous/asynchronous psychoeducation program for family caregivers of persons living with dementia. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, G.S.; Epps, F.; Dye, C.E.; Hepburn, K.; Higgins, M.K.; Parker, M.L. The effect of the “great village” on psychological outcomes, burden, and mastery in African American caregivers of persons living with dementia. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 39, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding-Wilson, K.N.; Guzmán-Vélez, E.; Angelica, J.; Wiggs, K.; Savransky, A.; Tranel, D. A novel two-day intervention reduces stress in caregivers of persons with dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2018, 4, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo-Benítez, J.; Cruz-Quintana, F.; Fernández-Alcántara, M.; Pérez-Marfil, M.N. Intervention program to improve grief-related symptoms in caregivers of patients diagnosed with dementia. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 628750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hives, B.; Buckler, J.; Weiss, J.; Schilf, S.; Johansen, K.; Epel, E.; Puterman, E. The effects of aerobic exercise on psychological functioning in family caregivers: Secondary analyses of a randomized controlled trial. Ann. Behav. Med. 2021, 55, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, B.L. Cognitive-behavioral intervention for homebound caregivers of persons with dementia. Nurs. Res. 1999, 48, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawfik, N.M.; Sabry, N.A.; Darwish, H.; Mowafy, M.; Soliman, S. Psychoeducational program for the family member caregivers of people with dementia to reduce perceived burden and increase patient’s quality of life: A randomized controlled trial. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2021, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W.; Perkhounkova, Y.; Shaw, C.; Hein, M.; Vidoni, E.; Coleman, C. Supporting family caregivers with technology for dementia home care: A randomized controlled trial. Innov. Aging 2019, 3, igz037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Töpfer, N.F.; Sittler, M.C.; Lechner-Meichsner, F.; Theurer, C.; Wilz, G. Long-term effects of telephone-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for family caregivers of people with dementia: Findings at 3-year follow-up. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 89, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, M.D.; Czaja, S.J.; Martinovich, Z.; Carol, R.N.; Donna, M.S.W.; Schulz, R. E-Care: A telecommunications technology intervention for family caregivers of dementia patients. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 15, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Carrasco, M.; Domínguez-Panchón, A.I.; González-Fraile, E.; Muñoz-Hermoso, P.; Ballesteros, J. Effectiveness of a psychoeducational intervention group program in the reduction of the burden experienced by caregivers of patients with dementia. EDUCA II Randomized Trial. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2014, 28, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söylemez, B.A.; Küçükgüçlü, Ö.; Buckwalter, K.C. Application of the progressively lowered stress threshold model with community-based caregivers: A randomized controlled trial. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2016, 42, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwig, M.; Heinrich, S.; Spahlholz, J.; Hallensleben, N.; Brähler, E.; Gertz, H.J. Individualized support for informal caregivers of people with dementia: Effectiveness of the German adaptation of REACH II. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehinejad, S.; Jannati, N.; Azami, M.; Mirzaee, M.; Bahaadinbeigy, K. A web-based information intervention for family caregivers of patients with Dementia: A randomized controlled trial. J. Inf. Sci. 2022, 50, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farran, C.J.; Paun, O.; Cothran, F.; Etkin, C.; Rajan, K.B.; Eisenstein, A.; Navaie, M. Impact of an individualized physical activity intervention on improving mental health outcomes in family caregivers of persons with dementia: A randomized controlled trial. AIMS Med. Sci. 2016, 3, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madruga, M.; Gozalo, M.; Prieto, J.; Rohlfs Domínguez, P.; Gusi, N. Effects of a home-based exercise program on mental health for caregivers of relatives with dementia: A randomized controlled trial. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021, 33, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, A.; Umegaki, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Kuzuya, M. Effects of leisure activities at home on perceived care burden and the endocrine system of caregivers of dementia patients: A randomized controlled study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J.A.; Black, B.S.; Johnston, D.; Hess, E.; Leoutsakos, J.M.; Gitlin, L.N.; Rabins, P.V.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Samus, Q.M. A randomized controlled trial of a community-based dementia care coordination intervention: Effects of MIND at home on caregiver outcomes. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwingmann, I.; Hoffmann, W.; Michalowsky, B.; Dreier-Wolfgramm, A.; Hertel, J.; Wucherer, D.; Eichler, T.; Kilimann, I.; Thiel, F.; Teipel, S.; et al. Supporting family dementia caregivers: Testing the efficacy of dementia care management on multifaceted caregivers’ burden. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terracciano, A.; Artese, A.; Yeh, J.; Edgerton, L.; Granville, L.; Aschwanden, D.; Luchetti, M.; Glueckauf, R.; Stephan, Y.; Sutin, A.; et al. Effectiveness of powerful tools for caregivers on caregiver burden and on care recipient behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabalegui-Yárnoz, A.; Navarro-Díez, M.; Cabrera-Torres, E.; Gallart-Fernández, A.; Bardallo-Porras, D.; Rodríguez-Higueras, E.; Gual-García, P.; Fernández-Capo, M.; Argemí-Remon, J. Eficacia de las intervenciones dirigidas a cuidadores principales de personas dependientes mayores de 65 años. Una revisión sistemática. Rev. Española de Geriatría y Gerontol. 2008, 43, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Encinas-Monge, C.; Hidalgo-Fuentes, S.; Cejalvo, E.; Martí-Vilar, M. Interventions to Relieve the Burden on Informal Caregivers of Older People with Dementia: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2535-2549. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030187

Encinas-Monge C, Hidalgo-Fuentes S, Cejalvo E, Martí-Vilar M. Interventions to Relieve the Burden on Informal Caregivers of Older People with Dementia: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(3):2535-2549. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030187

Chicago/Turabian StyleEncinas-Monge, Celia, Sergio Hidalgo-Fuentes, Elena Cejalvo, and Manuel Martí-Vilar. 2024. "Interventions to Relieve the Burden on Informal Caregivers of Older People with Dementia: A Scoping Review" Nursing Reports 14, no. 3: 2535-2549. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030187

APA StyleEncinas-Monge, C., Hidalgo-Fuentes, S., Cejalvo, E., & Martí-Vilar, M. (2024). Interventions to Relieve the Burden on Informal Caregivers of Older People with Dementia: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports, 14(3), 2535-2549. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030187