Abstract

Background/Objectives: The use of coercive measures (CMs) and security technologies (STs) in mental healthcare continues to raise ethical and practical concerns, affecting both patient and staff well-being. Mental health nurses (MHNs) and nursing students (NSs) play a key role in the decision-making process regarding these interventions. However, their attitudes, particularly toward STs, remain underexplored in Italy. This study protocol aims to introduce a new conceptual framework and investigate Italian MHNs’ and NSs’ attitudes toward CMs and STs in mental health settings. Additionally, it will explore the influence of sociodemographic and psychological factors, including stress, anxiety, depression, stigma, and humanization on these attitudes. Methods: The research will be conducted in two phases. Phase 1 involves a national survey of a convenience sample of MHNs and NSs to assess their attitudes and related factors. Phase 2 includes qualitative interviews with a purposive sample of MHNs and NSs to explore participants’ perspectives on STs in more depth. Quantitative data will be analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics, while qualitative data will be examined through thematic analysis. Conclusions: This study protocol seeks to enhance our understanding of MHNs’ and NSs’ attitudes toward the use of CMs and STs in mental health settings, identifying key factors influencing these attitudes. The findings aim to inform policy development, education programs, and clinical practices in both the Italian and international panoramas. Additionally, the proposed conceptual framework could guide future research in this field.

Keywords:

nursing; mental health; psychiatry; security measures; coercion; technologies; safety; attitudes 1. Introduction

The primary aim of psychiatric care is ‘to keep patients and others safe’ [1], highlighting the value of safety in mental health [2]. However, mental health settings face several challenges that can compromise safety [3]. These challenges include patient falls [4], adverse reactions to therapeutic interventions [5], and difficult patient behaviors, such as absconding [6]. Violence remains a critical issue, with a significant number of psychiatric inpatients exhibiting violent behavior [7], engaging in self-harm, or revealing suicidal tendencies [8]. Furthermore, up to 85% of mental health staff report experiencing assaults [9], which can lead to physical injuries [10] and psychological consequences [11].

1.1. Coercive Measures

These safety challenges are potential antecedents of coercion [12], precipitating the use of coercive measures (CMs) [13,14]. CMs are defined as ‘a medical measure carried out against the patient’s self-determined wishes or in spite of opposition’ [15]. Formal CMs include involuntary admission, observation, seclusion, forced medication, and restraint [12], while informal CMs encompass practices such as persuasion, manipulation, and threat [16].

Despite their common use, CMs raise significant concerns [12]. Patients subject to CMs may experience fear, anger, trauma [17,18], physical injury, or even death [19]. Staff implementing CMs can face the risk of physical harm [20], frustration, guilt, and ethical dilemmas [21,22,23]. Additionally, CMs can damage therapeutic relationships, infringe on patients’ rights, and reinforce stigma [12,24]. Although policies such as the Safewards Model [25] have shown promise to reduce CMs, they remain prevalent in contemporary mental health practices [26], and mental health staff still consider CMs necessary for maintaining safety [27,28].

1.2. Security Technologies

In light of the challenges and ethical concerns surrounding CMs, there is growing interest in alternative strategies to enhance safety in mental healthcare [29,30]. One emerging solution is the use of security technologies (STs), such as surveillance cameras, body-worn cameras, personal or fixed alarms, and metal detectors [31,32,33,34]. These technologies can enhance safety by enabling remote patient monitoring [31], facilitating rapid incident response [35], and preventing the introduction of dangerous items [32]. International guidelines support the use of STs such as surveillance cameras and alarms to mitigate suicide and violence in mental health [36,37], while in Italy, psychiatric forensic facilities already integrate them [38] following national policies [39,40].

However, research on the use of STs in mental health settings is still emerging [31,33,34]. While some studies highlight their values in enhancing safety and well-being [32,41], others identify potential risks, including increased property damage and violence [42,43]. Ethical concerns related to patient consent, privacy, and dignity also complicate their adoption [31,44,45].

1.3. The Role of Mental Health Nurses and Nursing Students

Mental health nurses (MHNs) are crucial in ensuring safety in psychiatry, also using CMs [46]. Therefore, extensive research has reviewed MHNs’ attitudes toward CMs [21,23,29], highlighting mixed findings and the need for further studies [23,27,29]. For instance, MHNs’ attitudes toward CMs are underexplored in Italy [47], with studies predominantly focused on general attitudes toward mental illness [48] and informal coercion [49]. Similarly, while international research is beginning to explore MHNs’ perspectives on certain STs such as body cameras [33,44,45], exploration of the attitudes towards an extensive range of STs is still lacking.

Nursing students (NSs) also participate in psychiatric care during their internship [50,51]. They actively witness, assist, and implement CMs [52,53], and can develop favorable attitudes toward them [53,54,55]. Furthermore, their perceptions could strongly predict the application of CMs [56]. However, despite their involvement, NSs’ attitudes toward both CMs and STs are underexplored.

1.4. Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework guiding this research integrates Johansen’s [57] and Moylan’s [58] decision-making models, enriched by key theoretical insights from the literature. Johansen’s model highlights how education, experience, values, knowledge, and stress influence decision-making in nursing practice [57]. Moylan’s model focuses on how MHNs navigate among perceived risks, available information, and personal values when selecting CMs in response to patient aggression [58]. Both models are pertinent to MHNs, who are described as ‘leaders during the application of restrictive practices in psychiatry’ [59], with substantial responsibility for initiating CMs [27].

This framework is further supported by the Theory of Planned Behaviour [60] and the Normative-Affective Decision-Making Theory [61], which highlights how beliefs, social norms, and emotional factors shape attitudes and behaviors. This aligns with existing research suggesting that both personal and normative factors have a strong influence on attitudes toward the use of CMs and STs [23,62,63].

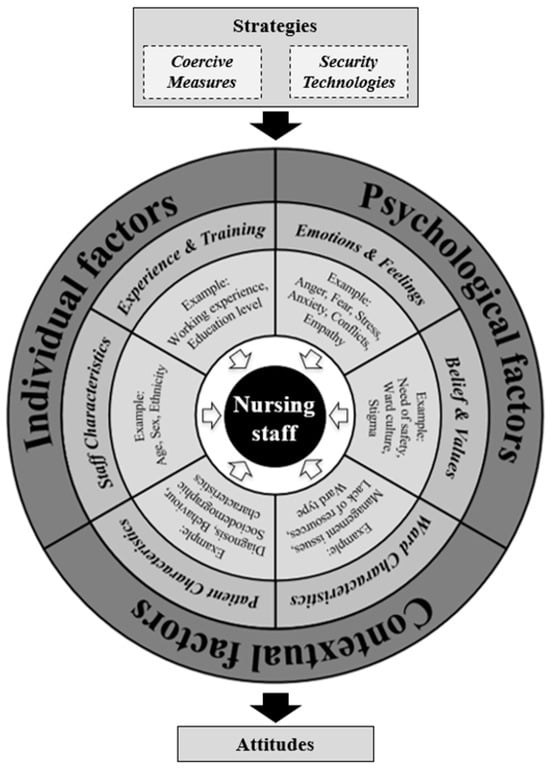

Based on these models and the existing literature, the proposed framework (see Figure 1) suggests that MHNs’ and NSs’ attitudes toward CMs and STs are shaped by three main categories of factors: individual, psychological, and contextual factors.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework with the factors involved in shaping the attitudes toward coercive measures and security technologies in mental health nursing.

1.4.1. Individual Factors

Staff characteristics: Evidence suggests that sociodemographic characteristics may influence attitudes and behaviors toward the use of CMs. Male MHNs are more likely to use CMs compared to females [13,14,64,65]. Shifts involving male MHNs have been associated with increased use of CMs [63]. Male NSs also express greater confidence in applying CMs [54,66]. However, some research suggests that female MHNs may exhibit more favorable attitudes toward CMs [65], with their presence linked to higher rates of seclusion [67]. Age is another important factor: younger MHNs tend to be more supportive of CMs [68], while older MHNs often express ethical concerns [69]. Additionally, MHNs’ ethnicity has been identified as influencing CMs’ use [70].

Experience and Training: The relationship between experience, training, and attitudes toward CMs is complex, with research providing mixed results. Some studies indicate that higher education correlates with increased CMs use [63,64], while others show that more educated MHNs are less supportive [14,67]. Work experience also plays a significant role. More experienced MHNs often resort to CMs less frequently [67], and hold critical views on their use [22,66]. In contrast, some studies report that experienced MHNs continue using CMs consistently [68,71,72]. Less experienced MHNs may view CMs as beneficial interventions [73], and adopt more restrictive approaches [65,67,73]. Additionally, feelings of being underskilled [74] or inexperienced in mental health nursing [64,75] are associated with higher reliance on CMs.

1.4.2. Psychological Factors

Emotions and Feelings: Emotional states can influence decisions to use CMs in psychiatric settings. Emotions such as anger, fear, stress, and anxiety can increase the likelihood of MHNs resorting to CMs [28,46,68]. Stress and anxiety can undermine MHNs’ confidence in managing aggression, increasing their reliance on CMs [22]. NSs show similar tendencies, supporting the use of CMs when experiencing anxiety and fear [76]. Additionally, team dynamics and interpersonal conflicts among nursing staff are linked to higher CM use [25,77]. Conversely, positive emotional traits such as empathy are associated with a reduced likelihood of employing CMs [78].

Beliefs and Values: Beliefs and values can shape MHNs’ attitudes toward CMs. A greater perception of risk is typically associated with increased use of CMs [29,79]. Similar trends are observed among NSs [76]. Ward culture and norms further influence the acceptance or rejection of CMs [72,73,75,80], leading to variations in CM use across units and countries [13,64]. Familiarity with CMs also predicts more favorable attitudes among MHNs and NSs [54,55,66,76,81]. Additionally, stigma toward mental illness, common among MHNs and NSs [82,83], can influence the approval of CMs [84].

1.4.3. Contextual Factors

Ward characteristics: The wards’ physical environment and operational structure can influence the use of CMs [80]. Working in open versus closed units, or acute versus chronic settings, shapes MHNs’ attitudes toward CMs [64,65,71,77]. Heavy workloads and staffing shortages increase the likelihood of using CMs, as MHNs may lack sufficient resources to manage incidents effectively [79,85]. For instance, shifts with less experienced staff are linked to higher CMs use [64]. Additionally, poor leadership, inadequate safety protocols, and organizational dysfunction contribute to increased reliance on CMs [74,77].

Patient characteristics: Patient-specific factors, such as diagnosis severity and type, are key determinants in decisions to implement CMs [13,85,86]. Patients exhibiting aggressive behaviors or refusing treatment are more likely to experience CMs [14,62,63,65]. Sociodemographic factors also play a role: patient sex [13,71,86,87], age [13], ethnicity [13,87], and marital status [87] can influence CMs use. Additionally, patients admitted involuntarily are more likely to be subjected to CMs compared to voluntary admissions [13].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Hypothesis

Based on the literature and the conceptual framework developed, the following research hypotheses were formulated:

- (1)

- Attitudes toward coercive measures and security technologies in psychiatric settings differ between mental health nurses and nursing students.

- (2)

- In mental health nurses and nursing students, attitudes toward coercive measures and security technologies in psychiatric settings vary depending on the specific type of strategy considered.

- (3)

- In mental health nurses and nursing students, attitudes toward coercive measures and security technologies in psychiatric settings are influenced by sociodemographic and psychological variables, including levels of depression, anxiety, stress, stigma toward mental illness, and humanization of care.

2.2. Objectives

The primary aims of the research are as follows:

- Assess the attitudes of mental health nurses and nursing students toward coercive measures and security technologies in Italian psychiatric settings.

- Investigate the associations between these attitudes and sociodemographic and psychological variables in mental health nurses and nursing students.

The secondary aim is as follows:

- Qualitatively explore the perspectives of mental health nurses and nursing students regarding the appropriateness of security technologies in mental health settings.

2.3. Project Design and Phases

This project adopts a non-experimental, mixed-methods, multicenter design, with an estimated duration of 12 months. It consists of two interdependent phases:

- Phase 1—Cross-sectional National Survey: This phase addresses the primary objectives and serves as the foundation for the protocol. A national survey will provide a comprehensive ‘snapshot of how things are at a specific time’ [88]. This approach effectively identifies trends and variations across populations, addressing gaps in existing research [89,90]. The survey will adhere to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology) guidelines to ensure rigor [91].

- Phase 2—Qualitative Descriptive Study: Building on the survey findings, this phase focuses on the secondary aim. The rationale for conducting a qualitative descriptive study is to ‘provide straightforward descriptions of experience and perceptions’ [92]. This approach is recommended in mixed-methods research to further explore quantitative results [92]. The study will adhere to the COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) guidelines to ensure quality and transparency [93].

2.4. Study Population

In Italy, nursing education consists of a three-year university program leading to a bachelor’s degree in Nursing, designed to provide general nursing competencies [94]. This program can offer exposure to mental health knowledge through multidisciplinary courses and internships within National Health Service institutions [95]. However, research indicates that national nursing curricula show considerable variability and lack standardization [96,97], and Italian nurses often graduate with limited psychiatric nursing education [47]. Furthermore, while post-graduate courses in mental health nursing are available, they are not mandatory for employment in psychiatric settings [98]. Based on this context, the study population is defined as follows:

- Nursing students: Students enrolled in a general nursing program, regardless of year of study, theoretical training, or mental health internship experience.

- Mental health nurses: Nurses employed in mental health settings, regardless of specialized training in mental health nursing.

2.5. Phase 1: Cross-Sectional National Survey

2.5.1. Sample and Sampling Procedure

Given the impracticality and costs of collecting data from the entire target population [89], this study will use convenience and snowball sampling methods [89,99]. These methods ensure efficient recruitment while aiming to achieve a sample representative of the population of interest [89,99]. Participants will be selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) consent to participate; (2) proficiency in Italian; (3) students enrolled in a general nursing program; (4) nurses employed in a mental health setting. To ensure consistency and relevance in the responses, the following exclusion criteria will be applied: (1) students who have suspended their program for more than one year; (2) nurses who have suspended work for more than one year; (3) nurses with less than one year of work experience in mental health.

2.5.2. Recruitment Process

Recruitment will initially focus on MHNs employed at the University Hospital and NSs enrolled in the School of Nursing at the primary study center. Recruitment invitations will be distributed via institutional email and local announcements [99]. To ensure national representation, recruitment will extend beyond the primary center. Nursing directors and chief nurses from mental health departments and units across Italian hospitals will be contacted to facilitate survey dissemination among MHNs. Similarly, nursing professors at Italian universities will be contacted to assist in enrolling NSs. Additionally, to align with modern recruitment practices, social media platforms, national mental health nursing associations, and nursing forums will be used to disseminate the survey, engaging MHNs and NSs outside academic or institutional networks.

All potential participants will receive a cover letter explaining the study’s purpose, procedures, and ethical considerations, along with a link to the online questionnaire. Participation will require completing an informed consent form before accessing the survey, ensuring transparency, voluntary participation, and adherence to ethical standards.

2.5.3. Sample Size

According to the Italian Ministry of Health, there are 14,904 MHNs employed in public and private mental health settings across Italy [100]. Additionally, data from the Italian Ministry of University and Research indicate that 55,842 NSs are enrolled in nursing programs nationwide [101,102,103]. Given the lack of prior studies assessing attitudes toward CMs and STs among Italian MHNs and NSs, the prevalence of positive or negative attitudes in these populations is unknown. As a result, the prevalence will be assumed at 50%, which, according to the World Health Organization guidelines [104] and established methodologies for sample size determination in survey research [105], leads to the maximum sample size required.

The required sample size for each population will be determined using Cochran’s formula as outlined by Barlett and colleagues [105]:

where n = required sample size; t = t-value (1.96 for a 95% confidence interval in populations with more than 120 subjects); p = assumed proportion (0.5 for a prevalence of 50%); and e = acceptable margin of error. This formula has been used in other recent healthcare publications [106].

Using this approach, considering a 95% confidence interval, a 5% margin of error, and a 50% assumed prevalence for maximization, the sample size required is shown below:

Thus, to ensure the statistical significance of the results, the survey will include at least 384 participants from each population.

2.5.4. Data Collection and Questionnaire

Data will be collected using an online self-report questionnaire hosted on Google Forms ©, designed according to best practices in survey methodology [89]. Online surveys are particularly suitable for research on sensitive topics, as they promote honest responses, reduce social desirability bias, and enhance data reliability [107].

The questionnaire consists of seven sections with a total of 90 closed-ended items. The first section gathers sociodemographic information, the second collects professional or academic data (distinguishing between MHNs and NSs), and the third evaluates attitudes toward CMs and STs. The subsequent sections include three validated Italian instruments to measure psychological variables, and the final section assesses participants’ willingness to engage in the qualitative study.

Due to the lack of existing instruments to evaluate MHNs’ and NSs’ attitudes towards CMs and STs, the third section was developed by the authors. The method employed mirrors the approach used by Bowers and colleagues [108] in designing a survey to explore safety procedures and measures used in psychiatric units. The development process involved establishing the theoretical framework, performing a literature review, and conducting a focus group involving the authors and five experts: two mental health chief nurses, two nursing professors, and a statistician. To ensure clarity and relevance, content and face validity testing was conducted using established methodologies [109,110]. The content validity ratio (CVR) ranged from 0.60 to 1, exceeding the minimum threshold of 0.49 [111]. The item-level content validity index (I-CVI) ranged from 0.80 to 1, surpassing the cut-off of 0.70 [112]. Additionally, the scale-level content validity index (S-CVI/Ave) was 0.90, above the recommended threshold of 0.80 [109]. Evaluation of face validity further confirmed that the questions were clear, relevant, and applicable to the study’s objectives. Consequently, the items were deemed valid for administration.

The entire questionnaire was then tested on ten participants from each population to evaluate completion times, which ranged from 16 to 30 min. This length aligns with recommendations for maintaining participant engagement in online surveys [113]. The completion times are also consistent with the literature on web survey responses, where participants typically spend between one and ten seconds per question [114].

The questionnaire will be structured as follows:

- 1.

- Sociodemographic variables: In this six-item section, participants will provide demographic information including sex, age, marital status, ethnicity, and spiritual beliefs. They will also indicate their current role (MHN or NS) to ensure they receive the appropriate subsequent questions. The anticipated completion time is two minutes.

- 2a.

- Questions for MHNs: In this 14-item section, MHNs only will answer questions about their working role (i.e., clinical or chief nurse), educational level (e.g., bachelor’s or master’s degree), education in mental health nursing (i.e., yes or no), years of work experience, years of work experience in mental health, geographical region, work setting (i.e., acute, community, residential), contract type (i.e., permanent or fixed-term), work schedule (i.e., full-time or part-time), and work pattern (i.e., shift or daytime). They will also assess their perceived workplace safety, job satisfaction, intention to change work settings, and inclination to leave the profession, using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all; 5 = very). The anticipated completion time is five minutes.

- 2b.

- Questions for NSs: In this nine-item section, NSs only will be asked about the geographical region where their program is located, academic status (i.e., full-time or part-time student), year of enrolment, education in mental health nursing (i.e., yes or no), internship pattern (i.e., shift or daytime), and hours spent in mental health internships. Additionally, they will evaluate their academic satisfaction, intention to leave the program, and interest in working in the mental health field using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all; 5 = very). The anticipated completion time is four minutes.

- 3.

- Attitudes towards CMs and STs: In this eight-item section, participants will assess the appropriateness of CMs and STs commonly used in psychiatry according to the literature, including physical restraints, pharmacological restraints, locked ward doors, video surveillance systems, body-worn cameras, fixed alarms, portable alarms, and metal detectors. Responses will be collected using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all appropriate; 5 = very appropriate). The anticipated completion time is four minutes.

- 4.

- Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21): This 21-item scale measures levels of depression, anxiety, and stress [115]. Participants will report the frequency of symptoms experienced over the past week on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never; 3 = almost always). The total score for each dimension will be calculated. Internal consistency values are α = 0.82 for depression; α = 0.74 for anxiety; α = 0.85 for stress. The anticipated completion time is seven minutes.

- 5.

- Opening Minds Stigma Scale for Healthcare Providers (OMS–HC): This 12-item scale measures stigma towards mental illnesses, focusing on attitudes towards people with mental illnesses and disclosure of mental illness [116]. Participants will indicate their agreement with each statement using a 5-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater levels of stigma. Internal consistency values are α = 0.74 for stigma towards people with mental illness and α = 0.86 for stigma towards disclosure. The anticipated completion time is five minutes.

- 6.

- Healthcare Professional Humanization Scale (HUMAS-I): This 19-item scale evaluates the humanization of care across five dimensions: affection, self-efficacy, emotional understanding, optimistic disposition, and sociability [117]. Participants will rate the frequency of their experiences using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never; 5 = always). Aggregate scores will be calculated for each dimension and the overall scale. Internal consistency values are as follows: α = 0.87 for affection; α = 0.82 for self-efficacy; α = 0.81 for emotional understanding; α = 0.82 for optimistic disposition; α = 0.70 for sociability. The anticipated completion time is seven minutes.

- 7.

- Willingness to participate in an interview: A dichotomous question (yes/no) will determine participants’ willingness to engage in the interview.

2.5.5. Data Analysis

Descriptive and bivariate statistical methods will be used to analyze the data. Frequencies, percentages, medians, means (Ms), standard deviations (SDs), and quartiles will be calculated for all variables. To verify the assumptions required for parametric testing, normality will be assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances will be evaluated with Levene’s test [118]. Correlations will be investigated through Pearson’s correlation for normally distributed continuous data, while Spearman’s rho will be used for non-normally distributed continuous data, ordinal data, or data with relevant outliers [119]. Differences in attitudes between groups will be assessed using independent samples t-tests for two-group comparisons and one-way ANOVA for comparisons involving more than two groups [120]. Significant findings from ANOVA will be further analyzed with Tukey post hoc tests to identify group differences. Potential confounding variables, such as sociodemographic and psychological factors, will be controlled through stratification, ensuring that these variables remain constant within subgroups [121]. Missing data will be excluded from the dataset to mitigate the risk of bias. All statistical analyses will be performed using SPSS© software (version 26), with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

2.6. Phase 2: Qualitative Descriptive Study

2.6.1. Sample and Sampling Procedure

For the qualitative phase of the project, a purposive sampling strategy will be employed. This strategy, with a focus on maximum variation, is recommended for qualitative research as it ensures a heterogeneous sample, allowing information-rich cases to be selected [122,123]. This approach is needed to capture a wide range of perspectives and experiences related to the research topic [92]. Participants will have the option to indicate their willingness to join the qualitative phase (Phase 2) by responding to the final question of the questionnaire administered in Phase 1. Sampling will thus be performed on the MHNs and NSs who expressed their willingness to participate in the interview.

2.6.2. Recruitment Process

The recruitment strategy will ensure comprehensive representation across key demographic variables, such as sex, age, geographical location, and educational background, enhancing the richness and diversity of the data. Recruitment will continue until data saturation is achieved, defined as the point at which no new information or themes emerge from the data [124]. Data saturation is considered the gold standard in qualitative research [122,125,126], ensuring the thoroughness and reliability of the findings [125,127]. Participants will be contacted via the email address provided in Phase 1. They will receive an invitation that includes a cover letter with detailed study information, informed consent forms, and options for scheduling the interview.

2.6.3. Sample Size

In the literature, data saturation in qualitative research typically occurs between nine and 17 interviews [126,128], with saturation often reached around the 12th interview [125,128]. Accordingly, the initial target is to conduct interviews with 15 MHNs and 15 NSs. However, since qualitative research is inherently iterative, involving concurrent sampling, data collection, and analysis [128], recruitment and interviews will continue if initial rounds do not achieve saturation.

2.6.4. Data Collection and Interview

Qualitative data will be collected through semi-structured interviews, each lasting approximately 60 min. To ensure participant comfort and enhance data quality, interviews will be conducted in the format preferred by the participant, whether in-person, by telephone, or online via videoconferencing software (Google Meets ©, version 280.0). Providing this flexibility helps create a setting that encourages open and genuine disclosure [129].

The interviews will use open-ended questions derived from the literature, designed to explore participants’ perceptions in depth and generate richer data [130]. Open-ended questions allow participants to express their insights freely, ensuring the data reflect the complexity of their experiences. All interviews will be audio-recorded with participants’ consent to enable precise transcription and ensure the data are captured verbatim [131]. Additionally, researchers will take detailed notes during interviews to document non-verbal cues and contextual details that may not be captured in the audio recordings [124].

The interview will be guided by five prompting questions (see Table 1), designed to generate detailed responses on both practical and ethical considerations regarding the use of STs in psychiatric settings.

Table 1.

Structure of the interview.

2.6.5. Data Analysis

Data analysis will be conducted using NVivo® software (version 14) and will adopt an inductive approach following the classic method of content analysis [92,123]. The dataset will include interview transcriptions and detailed notes taken during the interviews. These transcriptions will be digitally processed to facilitate the coding, identification of categories, and abstraction into themes. The analysis will involve two coding cycles: preliminary coding and targeted coding [132]. In the first cycle, open coding will be used to assign board labels to data segments, briefly describing their content. During the second cycle, these preliminary codes will be refined and synthesized into specific themes that accurately reflect participants’ experiences and perspectives.

2.6.6. Rigor

To ensure rigor and trustworthiness, the criteria established by Lincoln and Guba [124] will be followed. These criteria are widely recognized as the gold standard for ensuring the reliability and validity of qualitative research [92,127]. The following strategies will be employed to uphold these criteria:

- Bracketing (Suspension of Judgment): Researchers will set aside any preconceptions or biases during data collection and analysis to ensure objectivity and minimize potential bias.

- Coding Manual (Codebook): A structured codebook will be developed to guide the coding process, ensuring consistency, transparency, and coherence in interpretation.

- COREQ Checklist: The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist [93] will be used to ensure comprehensive and transparent documentation of the study’s procedures and findings.

To further enhance the validity of the findings, the identified themes will be presented to participants in follow-up interviews. This process allows participants to confirm the accuracy of the researcher’s interpretations or suggest adjustments, thereby strengthening the credibility and validity of the results.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The research protocol has been reviewed and approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Palermo 1 (protocol number 204/2024, dated 28 March 2024). The project adheres to international ethical standards, including the Declaration of Helsinki [133], Good Clinical Practice (Ministerial Decree 15/07/1997 and subsequent amendments), and the Oviedo Convention. It also complies with Italian laws about non-interventional studies, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) 2016/679, and the Italian Personal Data Protection Code (Legislative Decree 101/2018).

Participants will receive comprehensive information about the study, including its purpose, procedures, the voluntary nature of participation, and the right to withdraw at any time without consequences. They will be informed about confidentiality, anonymity, and data management. Informed consent will be required according to the Italian Legislative Decree n. 196 of 30 June 2003. Signed consent forms and collected data will be securely stored on a password-protected hard disk drive, accessible only to the principal investigators. Personal information, such as email addresses, will be used only for communication purposes and excluded from data analysis. Data will be presented in an aggregate form, and any personal identifiers will be replaced with pseudonyms or codes. Data will not be shared with third parties and will be destroyed after the dissemination of the results. Data destruction will be conducted by reformatting the drive. The study does not involve minors, clinical trials, or any direct physical or psychological risks to participants. No financial compensation will be offered to participants and the research team.

2.8. Limitations and Future Research

Despite the rigorous design of this protocol, certain limitations must be acknowledged. First, in Phase 1, the use of convenience sampling may introduce selection bias, as participants who are more accessible or willing to participate may not fully represent the study populations. Second, the reliance on self-report questionnaires could lead to social desirability bias, where respondents may modify their answers to align with social norms. Additionally, the convenience sampling method may lead to an uneven geographical distribution of participants, which could affect the generalizability of the findings across different regions of Italy. However, these limitations are recognized challenges inherent in survey research design [89,90]. Finally, the success of Phase 2 is dependent on participants’ willingness to be re-contacted for interviews, which may lead to a sample biased toward individuals with stronger opinions or greater engagement with the research topic.

These limitations highlight the challenges in conducting large-scale mixed-methods research. To address these issues, future studies could incorporate randomized sampling techniques and longitudinal designs to improve data robustness and generalizability.

3. Conclusions

This research protocol presents a new conceptual framework and aims to explore the attitudes of Italian MHNs and NSs toward the use of CMs and STs in psychiatric settings. It also aims to investigate the influence of sociodemographic and psychological factors on these attitudes. The significance of this project lies in addressing critical gaps in the literature, particularly regarding the attitudes and ethical concerns associated with the use of these strategies in Italian mental health nursing practice.

While the actual conclusions will be determined by the study’s outcomes, this research is positioned to make valuable contributions to psychiatric clinical care. Employing both quantitative and qualitative methods, the research will provide a comprehensive understanding of the attitudes and perceptions of Italian MHNs and NSs regarding CMs and STs, offering context-specific insights relevant to Italy while contributing to broader European and international discussions. The analysis of correlations between attitudes, and sociodemographic and psychological factors holds the potential to inform improvements in psychiatric care, enhance safety protocols, and promote the overall well-being of patients and staff. Furthermore, the findings may offer valuable guidance for nursing education, emphasizing the importance of safety management, patient-centered care, and the humanization of mental health services. Finally, the proposed framework could be helpful in conducting future research in this area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A. and S.B.; methodology, G.A., R.L., A.S. and S.B.; software, G.A., Y.L. and S.B.; validation, R.L., Y.L. and A.S.; formal analysis, G.A., Y.L. and S.B.; investigation, G.A., R.L., A.S. and S.B.; resources, R.L. and A.S.; data curation, G.A., R.L., A.S. and S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A.; writing—review and editing, R.L., A.S. and S.B.; visualization, G.A., Y.L. and S.B.; supervision, S.B.; project administration, G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Palermo 1 (protocol no. 204/2024, dated 28 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent will be obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted against the STROBE guidelines for observational research and the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ).

Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI or AI-assisted tools were not used in drafting any aspect of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the School of Nursing of the University of Palermo for its support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bowers, L.; Banda, T.; Nijman, H. Suicide inside: A systematic review of inpatient suicides. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010, 198, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slemon, A.; Jenkins, E.; Bungay, V. Safety in psychiatric inpatient care: The impact of risk management culture on mental health nursing practice. Nurs. Inq. 2017, 24, e12199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuomo, A.; Koukouna, D.; Macchiarini, L.; Fagiolini, A. Patient Safety and Risk Management in Mental Health. In Textbook of Patient Safety and Clinical Risk Management; Donaldson, L., Ricciardi, W., Sheridan, S., Tartaglia, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 287–298. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, K.; Bjarnadottir, R.; Jo, A.; Repique, R.J.R.; Thomas, J.; Green, J.F.; Staggs, V.S. Patient Falls and Injuries in U.S. Psychiatric Care: Incidence and Trends. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iuppa, C.A.; Nelson, L.A.; Elliott, E.; Sommi, R.W. Adverse Drug Reactions: A Retrospective Review of Hospitalized Patients at a State Psychiatric Hospital. Hosp. Pharm. 2013, 48, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerace, A.; Oster, C.; Mosel, K.; O’Kane, D.; Ash, D.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Five-year review of absconding in three acute psychiatric inpatient wards in Australia. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 24, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weltens, I.; Bak, M.; Verhagen, S.; Vandenberk, E.; Domen, P.; van Amelsvoort, T.; Drukker, M. Aggression on the psychiatric ward: Prevalence and risk factors. A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, K.; Stewart, D.; Bowers, L. Self-harm and attempted suicide within inpatient psychiatric services: A review of the literature. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 21, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odes, R.; Chapman, S.; Harrison, R.; Ackerman, S.; Hong, O. Frequency of violence towards healthcare workers in the United States’ inpatient psychiatric hospitals: A systematic review of literature. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Leeuwen, M.E.; Harte, J.M. Violence against mental health care professionals: Prevalence, nature and consequences. J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2017, 28, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Oe, M.; Ishida, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Chiba, H.; Uchimura, N. Workplace Violence and Its Effects on Burnout and Secondary Traumatic Stress among Mental Healthcare Nurses in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chieze, M.; Clavien, C.; Kaiser, S.; Hurst, S. Coercive Measures in Psychiatry: A Review of Ethical Arguments. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 790886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beghi, M.; Peroni, F.; Gabola, P.; Rossetti, A.; Cornaggia, C.M. Prevalence and risk factors for the use of restraint in psychiatry: A systematic review. Riv. Psichiatr. 2013, 48, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, R.; Kvalvik, A.M.; Hynnekleiv, T. Attitudes to coercion at two Norwegian psychiatric units. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2011, 65, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences. Medical-ethical guidelines: Coercive measures in medicine. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2015, 145, w14234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotzy, F.; Jaeger, M. Clinical Relevance of Informal Coercion in Psychiatric Treatment-A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieze, M.; Hurst, S.; Kaiser, S.; Sentissi, O. Effects of Seclusion and Restraint in Adult Psychiatry: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusack, P.; Cusack, F.P.; McAndrew, S.; McKeown, M.; Duxbury, J. An integrative review exploring the physical and psychological harm inherent in using restraint in mental health inpatient settings. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 1162–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kersting, X.A.K.; Hirsch, S.; Steinert, T. Physical Harm and Death in the Context of Coercive Measures in Psychiatric Patients: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renwick, L.; Lavelle, M.; Brennan, G.; Stewart, D.; James, K.; Richardson, M.; Williams, H.; Price, O.; Bowers, L. Physical injury and workplace assault in UK mental health trusts: An analysis of formal reports. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 25, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, W.K.; Bressington, D.T. Nurses’ attitudes towards the use of physical restraint in psychiatric care: A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 29, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, E.; Moritz, S.; Lincoln, T.M.; Fischer, R.; Nagel, M. Coercion in psychiatry: A cross-sectional study on staff views and emotions. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 28, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laukkanen, E.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K.; Louheranta, O.; Kuosmanen, L. Psychiatric nursing staffs’ attitudes towards the use of containment methods in psychiatric inpatient care: An integrative review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 390–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hem, M.H.; Gjerberg, E.; Husum, T.L.; Pedersen, R. Ethical challenges when using coercion in mental healthcare: A systematic literature review. Nurs. Ethics 2018, 25, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, L. Safewards: A new model of conflict and containment on psychiatric wards. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, D.; Boland, C.; Carballedo, A. Current trends in restrictive interventions in psychiatry: A European perspective. BJPsych Adv. 2023, 29, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Harrow, A. Nurses’ attitudes to the use of seclusion: A review of the literature. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 19, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, T.; Baker, A.; Jackson, D. ’Only ever as a last resort’: Mental health nurses’ experiences of restrictive practices. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doedens, P.; Vermeulen, J.; Boyette, L.L.; Latour, C.; de Haan, L. Influence of nursing staff attitudes and characteristics on the use of coercive measures in acute mental health services-A systematic review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 27, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrman, H.; Allan, J.; Galderisi, S.; Javed, A.; Rodrigues, M. Alternatives to coercion in mental health care: WPA Position Statement and Call to Action. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 159–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appenzeller, Y.E.; Appelbaum, P.S.; Trachsel, M. Ethical and Practical Issues in Video Surveillance of Psychiatric Units. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustin, T.A. Reducing contraband in a psychiatric hospital through the use of a metal detector. Tex. Med. 2007, 103, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Foye, U.; Wilson, K.; Jepps, J.; Blease, J.; Thomas, E.; McAnuff, L.; McKenzie, S.; Barrett, K.; Underwood, L.; Brennan, G.; et al. Exploring the use of body worn cameras in acute mental health wards: A mixed-method evaluation of a pilot intervention. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasi, G.; Bambi, S. Utilization and effects of security technologies in mental health: A scoping review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 1561–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, V.; Knight, R.; Sarfraz, M.A. Personal safety among doctors working in psychiatric services. J. Hosp. Manag. Health Policy 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of Victoria. Surveillance (CCTV) and Privacy in Designated Mental Health Services. Available online: https://www.health.vic.gov.au/chief-psychiatrist/surveillance-and-privacy-in-designated-mental-health-services (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- The Royal College of Psychiatrists. CCQI: Standards for Inpatient Mental Health Services, 4th ed.; The Royal College of Psychiatrists: Leicester, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rivellini, G.; Pessina, R.; Pagano, A.M.; Giordano, S.; Santoriello, C.; Rossetto, I.; Babudieri, S.; Celozzi, C.; Lucania, L.; Manzone, M.L.; et al. Il sistema REMS nella realtà italiana: Autori di reato, disturbi mentali e PDTA. Riv. Psichiatr. 2019, 55, 83–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Ministry of Health. Recommendation No. 4: Prevention of Hospital Patient Suicide; Italian Ministry of Health: Rome, Italy, 2008.

- Italian Ministry of Health. Recommendation No. 8: Recommendation to Prevent Acts of Violence Against Healthcare Workers; Italian Ministry of Health: Rome, Italy, 2007.

- Stolovy, T.; Melamed, Y.; Afek, A. Video Surveillance in Mental Health Facilities: Is it Ethical? Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2015, 17, 274–276. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, C.; Pellett, O.; Coverdale, J.; Paton Simpson, G. Management of violence in the workplace: A New Zealand survey. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. Suppl. 2002, 412, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, T.; Shurmer, D.; Badham-May, S.; Ellis-Nee, C. The use of body worn video cameras on mental health wards: Results and implications from a pilot study. Ment. Health Fam. Med. 2019, 15, 859–868. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.; Foye, U.; Thomas, E.; Chadwick, M.; Dodhia, S.; Allen-Lynn, J.; Allen-Lynn, J.; Brennan, G.; Simpson, A. Exploring the use of body-worn cameras in acute mental health wards: A qualitative interview study with mental health patients and staff. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 140, 104456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foye, U.; Regan, C.; Wilson, K.; Ali, R.; Chadwick, M.; Thomas, E.; Allen-Lynn, J.; Allen-Lynn, J.; Dodhia, S.; Brennan, G.; et al. Implementation of Body Worn Camera: Practical and Ethical Considerations. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2024, 45, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigwood, S.; Crowe, M. ‘It’s part of the job, but it spoils the job’: A phenomenological study of physical restraint. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2008, 17, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, L.; Whittington, R.; Almvik, R.; Bergman, B.; Oud, N.; Savio, M. A European perspective on psychiatric nursing and violent incidents: Management, education and service organisation. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 1999, 36, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Olmo-Romero, F.; González-Blanco, M.; Sarró, S.; Grácio, J.; Martín-Carrasco, M.; Martinez-Cabezón, A.C.; Perna, G.; Pomarol-Clotet, E.; Varandas, P.; Ballesteros-Rodríguez, J.; et al. Mental health professionals’ attitudes towards mental illness: Professional and cultural factors in the INTER NOS study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 269, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenti, E.; Banks, C.; Calcedo-Barba, A.; Bensimon, C.M.; Hoffmann, K.-M.; Pelto-Piri, V.; Jurin, T.; Mendoza, O.M.; Mundt, A.P.; Rugkåsa, J.; et al. Informal coercion in psychiatry: A focus group study of attitudes and experiences of mental health professionals in ten countries. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, B.-J.; Huang, X.-Y.; Lin, M.-J. The first experiences of clinical practice of psychiatric nursing students in Taiwan: A phenomenological study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 3126–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimollahi, M. An investigation of nursing students’ experiences in an Iranian psychiatric unit. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 19, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daughtrey, L. Nursing students’ experiences of witnessing physical restraint during placements. Ment. Health Pract. 2023, 26, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagozoglu, S.; Ozden, D.; Yildiz, F.T. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Turkish intern nurses regarding physical restraints. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2013, 27, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missouridou, E.; Zartaloudi, A.; Dafogianni, C.; Koutelekos, J.; Dousis, E.; Vlachou, E.; Evagelou, E. Locked versus open ward environments and restrictive measures in acute psychiatry in Greece: Nursing students’ attitudes and experiences. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, N.K.; Bilgin, H.; Badırgalı Boyacıoğlu, N.E.; Kaya, F. Student nurses’ attitudes towards professional containment methods used in psychiatric wards and perceptions of aggression. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2014, 20, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.M. Nursing Students’ Experiences of Observing the Use of Physical Restraints: A Qualitative Study. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2023, 53, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, M.L.; O’Brien, J.L. Decision Making in Nursing Practice: A Concept Analysis. Nurs. Forum 2016, 51, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moylan, L.B. A Conceptual Model for Nurses’ Decision-making with the Aggressive Psychiatric Patient. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 36, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martello, M.; Doronina, O.; Perillo, A.; La Riccia, P.; Lavoie-Tremblay, M. Nurses’ Perceptions of Engaging With Patients to Reduce Restrictive Practices in an Inpatient Psychiatric Unit. Health Care Manag. 2018, 37, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Selected Recent Advances and Applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, A. Normative-affective factors: Toward a new decision-making model. J. Econ. Psychol. 1988, 9, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiho, T.; Kattainen, E.; Astedt-Kurki, P.; Putkonen, H.; Lindberg, N.; Kylmä, J. Clinical decision making involved in secluding and restraining an adult psychiatric patient: An integrative literature review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 20, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowers, L.; Van Der Merwe, M.; Nijman, H.; Hamilton, B.; Noorthorn, E.; Stewart, D.; Muir-Cochrane, E. The practice of seclusion and time-out on English acute psychiatric wards: The City-128 Study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2010, 24, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelkopf, M.; Roffe, Z.; Behrbalk, P.; Melamed, Y.; Werbloff, N.; Bleich, A. Attitudes, opinions, behaviors, and emotions of the nursing staff toward patient restraint. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 30, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bregar, B.; Skela-Savič, B.; Kores Plesničar, B. Cross-sectional study on nurses’ attitudes regarding coercive measures: The importance of socio-demographic characteristics, job satisfaction, and strategies for coping with stress. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowers, L.; van der Werf, B.; Vokkolainen, A.; Muir-Cochrane, E.; Allan, T.; Alexander, J. International variation in containment measures for disturbed psychiatric inpatients: A comparative questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, W.; Noorthoorn, E.; Linge, R.; Lendemeijer, B. The influence of staffing levels on the use of seclusion. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2007, 30, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husum, T.L.; Bjørngaard, J.H.; Finset, A.; Ruud, T. Staff attitudes and thoughts about the use of coercion in acute psychiatric wards. Social. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2011, 46, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doeselaar, M.; Sleegers, P.; Hutschemaekers, G. Professionals’ attitudes toward reducing restraint: The case of seclusion in the Netherlands. Psychiatr. Q. 2008, 79, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowers, L. Association between staff factors and levels of conflict and containment on acute psychiatric wards in England. Psychiatr. Serv. 2009, 60, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maraira, O.A.; Hayajneh, F.A. Correlates of psychiatric staff’s attitude toward coercion and their sociodemographic characteristics. Nurs. Forum 2020, 55, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, N.K.; Bilgin, H.; Akın, M.; Badırgalı Boyacıoğlu, N.E. Nurses’ attitudes towards professional containment methods used in psychiatric wards and perceptions of aggression in Turkey. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 2881–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkeila, H.; Koivisto, A.M.; Paavilainen, E.; Kylmä, J. Psychiatric Nurses’ Emotional and Ethical Experiences Regarding Seclusion and Restraint. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 37, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerace, A.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Perceptions of nurses working with psychiatric consumers regarding the elimination of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric inpatient settings and emergency departments: An Australian survey. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzano-Bort, Y.; Mir-Abellán, R.; Via-Clavero, G.; Llopis-Cañameras, J.; Escuté-Amat, M.; Falcó-Pegueroles, A. Experience of mental health nurses regarding mechanical restraint in patients with psychomotor agitation: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 2142–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, L.; Alexander, J.; Simpson, A.; Ryan, C.; Carr-Walker, P. Student psychiatric nurses’ approval of containment measures: Relationship to perception of aggression and attitudes to personality disorder. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedictis, L.; Dumais, A.; Sieu, N.; Mailhot, M.P.; Létourneau, G.; Tran, M.A.; Stikarovska, I.; Bilodeau, M.; Brunelle, S.; Côté, G.; et al. Staff perceptions and organizational factors as predictors of seclusion and restraint on psychiatric wards. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 62, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.P.; Hargreaves, W.A.; Bostrom, A. Association of empathy of nursing staff with reduction of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric inpatient care. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usher, K.; Baker, J.A.; Holmes, C.; Stocks, B. Clinical decision-making for ’as needed’ medications in mental health care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danda, M.C. Exploring the complexity of acute inpatient mental health nurses experience of chemical restraint interventions: Implications on policy, practice and education. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2022, 39, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, L.; Alexander, J.; Simpson, A.; Ryan, C.; Carr-Walker, P. Cultures of psychiatry and the professional socialization process: The case of containment methods for disturbed patients. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, K.; Liu, J.; Jackman, K. Stigma towards patients with mental illness: An online survey of United States nurses. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, N.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y. The factors and outcomes of stigma toward mental disorders among medical and nursing students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, S.; Moeller, J.; Sowislo, J.F.; Lieb, R.; Lang, U.E.; Huber, C.G. General and Case-Specific Approval of Coercion in Psychiatry in the Public Opinion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lay, B.; Nordt, C.; Rössler, W. Variation in use of coercive measures in psychiatric hospitals. Eur. Psychiatry 2011, 26, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.L.; Baiden, P.; Theall-Honey, L. Factors associated with the use of intrusive measures at a tertiary care facility for children and youth with mental health and developmental disabilities. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 22, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, C.; Starkopf, L.; Hastrup, L.H.; Andersen, P.K.; Nordentoft, M.; Benros, M.E. Risk factors of coercion among psychiatric inpatients: A nationwide register-based cohort study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denscombe, M. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects, 3rd ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, K.; Clark, B.; Brown, V.; Sitzia, J. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2003, 15, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rea, L.M.; Parker, R.A. Designing and Conducting Survey Research: A Comprehensive Guide; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13, S31–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, L.; McCabe, C.; Keogh, B.; Brady, A.; McCann, M. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italian Ministry of Health. D. M. 14 September 1994, n. 739. Regulation Concerning the Identification of the Nurse and Corresponding Professional Nursing Profile. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1995/01/09/095G0001/sg (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Gonella, S.; Brugnolli, A.; Randon, G.; Canzan, F.; Saiani, L.; Destrebecq, A.; Terzoni, S.; Zannini, L.; Mansutti, I.; Dimonte, V.; et al. Nursing students’ experience of the mental health setting as a clinical learning environment: Findings from a national study. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2020, 56, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocco, G.; Affonso, D.D.; Mayberry, L.J.; Stievano, A.; Alvaro, R.; Sabatino, L. The Evolution of Professional Nursing Culture in Italy:Metaphors and Paradoxes. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2014, 1, 2333393614549372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latina, R.; Forte, P.; Mastroianni, C.; Paterniani, A.; Mauro, L.; Fabriani, L.; D’Angelo, D.; De Marinis, M.G. Pain Education in Schools of Nursing: A Survey of the Italian Academic Situation. Prof. Inferm. 2018, 70, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, P.; Brimblecombe, N. A survey of the education of nurses working in mental health settings in 12 European countries. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, S.J. Population Research: Convenience Sampling Strategies. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2021, 36, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Ministry of Health. Mental Health Report; Mental Health Information System Data Analysis. 2022. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/documentazione/p6_2_2_1.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=3369 (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Italian Ministry of University and Research. Ministerial Decree No. 794 of 13-7-2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.mur.gov.it/it/atti-e-normativa/decreto-ministeriale-n-794-del-13-7-2021 (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Italian Ministry of University and Research. Ministerial Decree No. 1113 of 1-7-2022. Available online: https://www.mur.gov.it/it/atti-e-normativa/decreto-ministeriale-n-1113-dell1-7-2022 (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Italian Ministry of University and Research. Ministerial Decree No. 1225 of 11-9-2023. Available online: https://www.mur.gov.it/it/atti-e-normativa/decreto-ministeriale-n-1225-dell11-9-2023 (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Lwanga, S.K.; Lemeshow, S.; World Health Organization. Sample Size Determination in Health Studies: A Practical Manual; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barlett, J.E.; Kotrlik, J.W.; Higgins, C.C. Organizational research: Determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Inf. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2001, 19, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Damor, N.; Makwana, N.; Kagathara, N.; Yogesh, M.; Damor, R.; Murmu, A.A. Prevalence and predictors of multimorbidity in older adults, a community-based cross-sectional study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2024, 13, 2676–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kays, K.M.; Keith, T.L.; Broughal, M.T. Best Practice in Online Survey Research with Sensitive Topics. In Advancing Research Methods with New Technologies; Sappleton, N., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, L.; Crowhurst, N.; Alexander, J.; Callaghan, P.; Eales, S.; Guy, S.; Mccann, E.; Ryan, C. Safety and security policies on psychiatric acute admission wards: Results from a London-wide survey. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2002, 9, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haladyna, T.M. Developing and Validating Multiple-Choice Test Items; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lawshe, C.H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, H. How short or long should be a questionnaire for any research? Researchers dilemma in deciding the appropriate questionnaire length. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2022, 16, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Tourangeau, R. Fast times and easy questions: The effects of age, experience and question complexity on web survey response times. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2008, 22, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottesi, G.; Ghisi, M.; Altoè, G.; Conforti, E.; Melli, G.; Sica, C. The Italian version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21: Factor structure and psychometric properties on community and clinical samples. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 60, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Destrebecq, A.; Ferrara, P.; Frattini, L.; Pittella, F.; Rossano, G.; Striano, G.; Terzoni, S.; Gambini, O. The Italian Version of the Opening Minds Stigma Scale for Healthcare Providers: Validation and Study on a Sample of Bachelor Students. Community Ment. Health J. 2018, 54, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelone, A.; Latina, R.; Anastasi, G.; Marti, F.; Oggioni, S.; Mitello, L.; Izviku, D.; Terrenato, I.; Marucci, A.R. The Italian Validation of the Healthcare Professional Humanization Scale for Nursing. J. Holist. Nurs. 2024, 0, 8980101241230289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Zahediasl, S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: A guide for non-statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 10, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Singh, U.; Pandey, C.M.; Mishra, P.; Pandey, G. Application of student’s t-test, analysis of variance, and covariance. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019, 22, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Baghestani, A.R.; Vahedi, M. How to control confounding effects by statistical analysis. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2012, 5, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, R.; Boulton, M. Qualitative methods for assessing health care. Qual. Health Care 1994, 3, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough?:An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korstjens, I.; Moser, A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janghorban, R.; Latifnejad Roudsari, R.; Taghipour, A. Skype interviewing: The new generation of online synchronous interview in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9, 24152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, J.; Cornwell, D. The role of topic, interviewee and question in predicting rich interview data in the field of health research. Sociol. Health Illn. 2010, 32, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, L.M.; Meyer, M.; Estable, A. Improving accuracy of transcripts in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).