Abstract

Sharing economy represents a new business model with an increasing impact on economic life by generating consequences for the traditional business sector. Considering its development during the last years, it is important to know how the governance system should react to the new challenges determined by this kind of doing business. The aim of the article is to identify and analyze some general issues regarding the impact on the sharing economy in tourism, based on a study regarding the needs determined by this business model in Brașov. Considering that tourism is a relevant sector for the “sharing” business type, the authors considered it important to get opinions about the way that the local authorities and stakeholders should contribute to the creation of a regulatory framework for sharing tourism, so, two focus-groups were organized. The respondents were chosen so that all kinds of stakeholders involved in tourism were represented. The results of the research revealed that even though there are some provisions regarding this sector, and despite the fact that local and regional authorities are preoccupied about regulations in sharing tourism, the most representative part of this sector is unregistered and it works according to its own rules.

1. Introduction

During the last years, the economic environment has been facing new, innovative types of business, which can contribute to the main goal of sustainable development—the long-term stability of the economy and environment [1]. Sustainable development is based on three pillars, environmental, social, and economic, and represents the development that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [2].

One of these types of business is the sharing economy, which represents “a rising pattern in consumption behavior that is based on accessing and reusing products to utilize idle capacity, presents both tremendous possibilities and significant threats for emerging as well as incumbent businesses” [3]. According to specialists, the sharing economy could change the business approach towards sustainability [4,5].

The sharing economy is framed by a series of characteristics that define it as a complex concept: an economic opportunity; a more sustainable form of consumption; a pathway to a decentralized, equitable, and sustainable economy; creating unregulated marketplaces; reinforcing the neoliberal paradigm; and an incoherent field of innovation [6]. Due to its fast growing nature, there are specialists who consider that the sharing economy will become a mainstream phenomenon, not a niche market [7].

The concept of a “sharing economy” is considered by a significant number of specialists as being similar to other concepts that define innovative economic models, such as: “collaborative consumption” [8,9,10,11], the “peer-to-peer economy” [12,13], the “gig economy” [14], the “on-demand economy” [15,16], and “crowd economies” [17].

There are some differences in the meaning of these concepts, but these differences do not change the principle that frames the business model. According to this principle, a process of “sharing” consumption, an “innovative exchange” of goods and services is taking place, marked by a number of differences consisting of details regarding the way that the user groups are created online, the user type, or their interest type, as follows:

- Collaborative consumption—sharing, swapping, trading, or renting, by creating continuous interaction (materialized in continuous exchanges) in a group, where the roles of owners and users/sellers and buyers are interchangeable;

- Peer-to-peer economy (P2P)—transactions made through a platform that facilitates transactions by matching anonymous or semi-anonymous supply and demand requests between private individuals;

- Collaborative economy—using online platforms, where trade takes place between individuals;

- Gig economy—an online platform connects potential employees with employers looking for temporary contract-based roles;

- On-demand economy—the online platform creates the possibility to have economic transactions in real-time;

- Crowd economy—a group of participants, connected through a platform, collaborate to achieve a mutual interest [18].

The sharing economy consists of a business model based on a special characteristic—private individuals share goods and services. Transactions are facilitated by online platforms where intermediary companies connect providers with users to try to create a sense of belonging to a virtual community that shares certain values [19]. By connecting people through online platforms, the sharing economy might be considered a consequence of the Web 2.0 stage, that permits users to not only access static websites (with no interactive contents), but, also, social web experiences, sharing experiences [20]. The online environment, as a main component of the sharing economy, reveals the fact that this type of doing business is a new digital business model, so it might be considered a “platform economy”, characterized by free/minimal labor, controlling quality, especially through consumer opinions and the increasing role of social media [21,22].

In these circumstances, a focus on analyzing the main issues regarding the sharing economy becomes more challenging from many points of view, and in the authors’ opinion, questions like “What is the relation between traditional types of economy and the innovative types of economy?”, “What are the main benefits and disadvantages of sharing economy?”, “What should be the possible solutions to achieve the right framework to assure a balanced and a proper environment both to traditional and new forms of economy?”, “Who are the main actors of the process and what kind of responsibilities and competences do they have?”, and “What is the limit when informal exchanges become collaborative consumption and when do they transform in business?” are just a few whose responses should provide important information about the future of the sharing economy. These questions were considered by the authors as a source of defining the concrete issues for research regarding a sharing economy, with a particular focus on tourism.

The current studies regarding the sharing economy point out that even though the sharing economy is in a continuous process of developing, this business model is in an infancy stage [23]. Despite this, the need to approach its challenges is recognized both at a global and European level. Recently, the World Economic Forum focused on the sharing economy’s development, by making a study of 10 cities around the world with the final purpose of releasing a whitepaper—Collaborating in Cities: From Sharing to Sharing Economy—in order to highlight the ways that cities should take into consideration the opportunities produced by the sharing economy and how they should be able to use these opportunities to raise city development [24].

In the European Union, according to the free movement of services (as a component of The Single Market), and according to the statistics (more than 70% of the EU’s GDP is provided by services), the services sector is appreciated as “the economic growth’s engine” [25]. In these circumstances, the development of services—including the sharing economy—is significant and increasing of the sharing economy becomes more of a reality in the European Union business environment [26].

For these reasons, the EU has paid special attention to this type of economy, by creating a special working agenda—The European Agenda for the Collaborative Economy Development—in order to support and to assist new sustainable business models [27]. The main purposes of this agenda were to make an assessment of some “key aspects” of regulations regarding the sharing economy and to invite the member-states to revise and to improve the national regulations, to create fair and honest premises for both kinds of economies—traditional and sharing (”Communication from the Commission to The European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee, and The Committee of Regions on the European Agenda for the collaborative economy”) [27].

This article was written with the scope of identifying and analyzing some general issues regarding the impact on the sharing economy in tourism, based on a study regarding the needs determined by this business model in Brașov. In this sense, the following objectives were established: (1) Identifying the stakeholders’ point of view regarding sharing tourism in Brașov; (2) highlighting the interconnection between sharing tourism and sustainable development; (3) pointing out the necessary elements of creating a legal framework in sharing tourism; (4) identifying the levels requested for assuring the legal frame of the sharing economy.

The main conclusions of the research refer to the fact that in Brașov, sharing tourism represents an increasing type of business, and the authorities are increasingly taking this new phenomenon into consideration, but, despite of the local efforts, there is a significant number of touristic service providers that work unregistered and unlicensed.

The article is structured in five parts: the premises of the research, methodology, results, discussions, and conclusions. Starting from the general scope of the paper, the authors present, at the beginning, the research premises—the international context of the sharing economy and some issues regarding sharing tourism; then, the research methodology is presented—both the desk research and the qualitative research methodology are detailed, for a better understanding of the way that the authors intended to get to the results; after presenting the general issues resulting from the research, the qualitative research results are detailed based on the variables from The European Agenda; considering the theoretical issues and the main results from the qualitative research, the authors then bring into discussion the way that authorities should get involved in sharing tourism development, and, also, the main conclusions of the research, both from a theoretical and practical point of view.

2. Premises of the Research

2.1. The International Context of Sharing Economy

As it was mentioned above, the World Economic Forum created an initiative regarding the sharing economy. The main reason of this preoccupation resides in the fact that the rise of population and the trend of living in urban areas require a new approach regarding the governance of cities, which should take into consideration activities including the sharing and circular economy, especially by considering new innovative and sustainable policies [28]. These requirements are based on at least two issues, under the frame of the contemporary social and economic trends:

- The rise of new forms of economy, with a 2016 global survey showing that platform companies have a total market value of $4.3 trillion and directly employ 1.3 million people [24];

- The specificity of the sharing economy (using digital platforms—the so called ”switching the corporation with the platform”; the relationship between ordering and using; the consequences of the relationship between owning and sharing; building trust in the sharing economy; the threats of the sharing economy to the traditional forms of doing business; the lack of a legal framework) [29]. At the European level, the preoccupations regarding the sharing economy are found in The European Agenda for the Collaborative Economy Development. The most important aspects refer to European preoccupations, but, also, the European documents highlight national measures—the requirements regarding market access, liability regimes, users’ protection, self-employed workers in the sharing economy, and taxation, as it results from Table 1 [27].

Table 1. Regulations regarding sharing economy in the European Union.

Table 1. Regulations regarding sharing economy in the European Union.

2.2. Sharing Economy in Tourism

The sharing economy has become a significant segment of the holiday accommodation market, considered an emergent economic-technological phenomenon fostered by developments in ICT, and considered both a disruptive innovation and a competitive threat to hotel companies, redesigning traditional business models by using the collaborative platforms [30,31,32]. In sharing tourism, the interaction between the service providers and consumers is completed by a personalized interaction between locals and consumers, so, as a consequence, in the tourism sector, the sharing economy builds an “online friendship” between local residents and tourists, with the locals being responsible for building a host-guest relationship inside the network [33]. At the same time, sharing in tourism refers to the fact that travelers, in their attempts to get authentic, experientially oriented opportunities, are helped to get these experiences by the interaction with the locals and the partnerships between travelers and locals, not only improve the traveler’s experience, but also to support the local community [34,35]. Airbnb—considered “the most prominent example of novel peer-to-peer networks in tourism” and “a particularly notable example in the field of tourism”—connects guests with hosts, allowing both to exchange cultural experiences, in addition to economic transaction [36,37,38]. A similar case is Uber, who has expanded to 67 countries in seven years [39].

The sharing economy in tourism has an impact not only on the local business environment, but also on the so-called secondary market entrepreneurs, with other areas but tourism being influenced by the travelers accommodated through sharing platforms—local trade, traditional tourism, and safety—and not all the influences are positive (for instance, in tourism, the traditional sector accommodation sector fights with the sharing accommodation sector to gain back market share) [40,41]. In addition, in the tourism sector, the sharing economy has a specific impact on sustainability, by assuring a planned, integrated, and properly coordinated orientation to environmental issues, economic activities, and society, and it also has a significant impact on social responsibility regarding the communities (CSR) by providing certain benefits not only for the hosts, but also for the locals and the cities, in general; so, local authorities become active “actors” in establishing and implementing regulations and policies in this field [42,43,44].

According to the “Study to monitor the business and regulatory environment affecting the collaborative economy in the EU”, the most representative business models affecting the collaborative economy in accommodation are two business models: short-term rentals and home swapping. In addition, there are some connected sectors with a high impact on tourism that are also well-represented with a high potential of growing in the EU: transport (ride sharing, car sharing, and ride hailing), support services (financial and nonfinancial support), and public administration [45]. In accommodation, there is a general openness to the sharing economy, with the best performances being in Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Ireland, Lithuania, Romania, Poland, Slovakia, and the United Kingdom, with few restrictions regarding authorizations and licenses having been requested. The distinction between peers and professionals is the clearest in Austria, Greece, Finland, Latvia, and Sweden; so, in these countries the authorities are able to quantify the sharing economy’s contribution to the development of cities/countries and, also, the traditional sector does not experience the so-called “unfair competition” from the new type of business [46].

2.3. Sharing Tourism in Brasov

Brașov is a county in the Center Region of Romania (one of the eight regions of Romania), with a population of 633,686 inhabitants in January 2018. The city of Brașov has 290,167 inhabitants. A short analysis of the official data provided by the National Office of Statistic Data [47] reveals that, in the first semester of 2018, Brașov County’s number of arrivals was the most representative in the region (42.5%); Brașov County had an increase of arrivals of 7.9%, compared with the same time in 2017. The accommodation capacity was assured as follows: 44.1%—hotels, 20.8%—agro-tourist guest houses, 17.7%—guest houses, 6.0%—villas, 3.5%—cottages, 2.8%—hostels, 2.4%—motels, and 2.7%—other accommodation units [47].

The natural and anthropic potential of Brașov creates the premises for the following forms of tourism: mountain tourism, cultural tourism, sport, leisure and recreation tourism, religious tourism, business and conference tourism, and medical tourism.

Regarding sharing tourism, the national law in Romania specifies that the limit required for the authorization to rent is a number of five rooms. Under this limit, there is no need to get the so-called “classification”; only registration at the fiscal authority is requested.

The national law regarding sharing tourism in Romania is represented by a common regulation act of two ministries—The Ministry of Regional Development and Tourism and The Ministry of Public Finance—The Common Order 22/28/2011. According to that, there are two alternatives for establishing the annual fiscal contribution of individuals involved in sharing tourism: a tax as a percent of the income (so, depending on the income) or an annual income given sum (so, an established sum, not depending on the income) [48].

The levels of taxes are established differently for each category of settlement, and they can be adjusted, depending on some criteria. For example, in Brasov, some of the following levels of reduction are applied: the settlement is situated on the urban level—5%; the room surface is less than 10 sm—5%; the access to touristic resources is realized only with own means of transport—10% [49].

According to official data, in August 2018 in Brasov county, a total of 1337 accommodation units were classified as rental service providers (individuals and firms), of which 307 are from the city of Brasov [50].

3. Methodological Approach

The research objectives are: identifying the stakeholders’ point of view regarding sharing tourism in Brașov; highlighting the interconnection between sharing tourism and sustainable development; pointing out the necessary elements of creating a legal framework in sharing tourism; and identifying the levels requested for assuring the legal frame of the sharing economy.

To achieve the purposes of the research, the authors were interested, at the beginning, in highlighting the specificity of “the sharing economy” concept, and in finding quantitative information about the actual status of sharing tourism in the European Union, so desk research was needed. Based on the desk research, the authors proposed to find information about sharing tourism in Brașov. Brașov was chosen based on the fact that the city is the second most touristic city in Romania, with a total of 1,275,299 of tourists [47], so the “experience” of the city regarding tourism was appreciated as relevant.

Desk research—a succession of secondary data analysis—was considered useful by the authors to establish a theoretical framework of the sharing economy (with a focus on tourism), to analyze the governance systems’ involvement in the sharing economy, and to get a market overview of sharing tourism. In order to accomplish these issues, the following sources were used:

- Academic literature;

- European and national reports and surveys;

- Websites dedicated to a collaborative economy.

The main outcomes of the desk research were the establishment of a multi-level governance approach regarding the sharing economy, and the establishment of whether there are enough data regarding sharing tourism to create a database in order to provide statistical data about this sector.

Qualitative research—consisting of two focus-groups—was considered useful to get information about sharing tourism (if sharing tourism exists in Brasov and how is it integrated into local policy; to explore the way that the local governance is involved in measuring and quantifying the contribution of this sector in the local and regional statistics; what the main lacks of legislation in the sector are and who should be the key actors in transposing the existing legislation into practice; technical issues regarding sharing tourism—authorization system, liability, user’s protection).

The variables in the interview guide were introduced based on the preoccupation from The European Agenda regarding collaborative economy [27], in order to find out how the local governance uses the necessary tools, what the main obstacles in regulating the sharing tourism are, and how Brasov authorities built a specific scheme of integrating sharing tourism in the local and regional economy. Using this method supposed the use of extensive discussions—more than 120 min for each focus group—with 14 persons (eight persons in the first focus group and six persons in the second). Sampling took into account criteria, such as occupation and position held within the represented organization, and giving them default answers—in this stage of the research—was considered a limitation of expressing their options.

The main reason that the authors have chosen this kind of research is because it was their intention to get information about the current status of sharing tourism in Brașov. In accordance with the qualitative research specificity, selecting the sample is conducted by the researchers by taking into consideration the domain’s importance in research, and, despite the fact that the sample has no statistical representativity, it is considered relevant for the research. To establish the sample dimension, the authors used the concept of “information power”, which means that “more information the sample holds, the lower amount of participants is needed” [51] and by taking into consideration the purpose of the study and the occupation and position of stakeholders, a number of 14 persons was estimated.

The number of respondents was chosen considering the public and private organizations involved in sharing tourism—The Ministry of Tourism, The City Council, The Fiscal Authority, some tourism accommodation units, real estate agencies, tourism associations, experts in tourism, and people involved in sharing tourism (Table 2).

Table 2.

Categories of respondents in the qualitative research.

The structure of the respondents was the following:

The qualitative research added support and deepened the aspects identified by the secondary data research method, giving the beneficiaries of this study a complete and profound picture of the situation existing in the Brașov municipality regarding the collaborative tourism compared to the existing situation at a national and European level.

In this research, which benefited from the emergence of participants’ ideas, aspects related to attitudes and motivations that cannot be communicated through monosyllabic responses were caught, with each participant developing their position due to the group expression of various opinions, in agreement or in contradiction with other opinions expressed.

Group discussions were conducted on the basis of a semi-structured interview guide, thus giving participants the opportunity to express their opinions freely and to initiate spontaneous discussions. The discussions were carried out by two experienced experts, with the purpose of obtaining the information concerned and to cover all the proposed topics, but without influencing the participants’ positions by expressing personal value judgments.

After receiving the participants, an introductive part followed; information about the recording conditions, the limits of confidentiality, and the conditions in which each will speak to the group were provided to the participants; their consent to use the information was obtained. At the same time, the participants were informed about the discussion rules, so they could express themselves freely, respecting the other participants’ opinions.

After each participant made a brief self-presentation, the concept of a “sharing economy” was explained, as evidenced from the literature. At the same time, the concepts of “sustainability” and “durability” based on the three pillars—economic, social, and environmental—were introduced in the discussion context, considering the fact that the participants knowing and understanding the significance of these terms was considered important.

Among the first researched issues was the identification of the perceptions of the subjects regarding the existence of the sharing economy at the level of the city of Brașov, and in this respect, the following questions were asked: “Do you think there is sharing economy in Brașov?”, “How extensive do you think is this economic phenomenon in Brașov?”, and “What is the situation of Brașov, compared to other cities?”

To capture the attitude of the subjects towards the impact of the sharing economy, three aspects were highlighted—economic, socio-cultural, and environmental—as follows:

- Economic impact—“What are the economic benefits of sharing economy of the sharing economy, in general?”;

- Socio-cultural impact—“If and how important are the benefits of sharing economy in the socio-cultural sphere?” and “Is it necessary that the socio-cultural information should be provided to tourist according to urban development strategies?”.

Also, in order to analyze the socio-cultural impact, the technique of interpreting a role—by which the subjects were asked to imagine that they were the person responsible for the image of Brașov—was used. The participants were asked to describe what they would do to frame the information provided by the hosts in the spirit of an urban development strategy.

- Environmental impact—the subjects were asked to balance two situations: on one hand, a hotel with 100 apartments, and on the other hand, 100 apartments rented by individuals in the sharing economy system. The subjects were asked to answer to questions, such as: “Which of the two structures affects more significant the environment—resource consumption, waste collection?” and “What kind of regulations would be needed to have a rational consumption of resources in the sharing economy?”

Another aspect discussed in the focus groups referred to the market access. The questions addressed to the subjects to get information about this issue were: “Would it be necessary to license/authorize this activity in an easier procedure, so that this form of economy wouldn’t be discouraged?”; “What would be the proper way to get the license/authorization?”; “What is the limit after which a person should be considered from a participant in sharing economy a touristic services provider?”; “Would it be necessary a limit over which the activity should be taxed?”; and “The collaborative platforms should be regulated and this regulations should be done? ”. Also, in order to investigate these aspects, the projection technique was used. The subjects were asked to complete the following sentence: “As regards the licensing/authorization of service providers in sharing economy I consider that …”

Another research objective consisted of identifying the respondents’ attitudes regarding the liability regime applicable to the “actors” involved in the sharing economy/tourism. For that, the subjects were asked about the responsibilities that suppliers/providers should have to help to create a favorable image of the city and how the consumers’ protection in this type of economy should be assured.

In order to capture the most subtle aspects of how participants appreciate the need to protect the consumers, a projective technique was used—the story telling technique—by which the subjects were asked to imagine a scenario in which there was a divergence of opinions between a family of dissatisfied tourists and the owner of a rented property. The participants were asked to answer a series of questions regarding the responsibility for the situation, the actions that the tourist should do, if it is appropriate that public authorities get involved, and if the city image has to suffer from this situation; as a result, a series of proposals for solving this situation was suggested.

In order to find out the subjects’ opinion regarding the employment in sharing tourism, the participants were asked to express their opinion about the employment regime of people working in sharing tourism. The last aspect of the focus groups referred to the tax regime in sharing tourism. For the emergence of ideas, questions such as: “If this type of activity should be taxed and how could this be done?”, “How can local taxes from sharing tourism could be collected?”, and “Should VAT be introduced in this type of economy?”, were asked.

In order to conclude the discussed issues regarding sharing tourism, the technique of completing sentences was used in the case of statements like: “The locals who provide touristic services through the system of sharing economy …” and “The institutions responsible for the development of the sharing economy are …”. Also, some questions that reveal an overview regarding this phenomenon were addressed: “What should be the possible solutions to create a reasonable framework to ensure a balanced and adequate environment for traditional forms and new types of economy?”, and “Who are the main actors of the process and what kind of responsibilities and competencies do they have?”.

In synthesis, Table 3 presents the connection between the variables and the related questions from the interview guide:

Table 3.

Connection between the variables and the related questions from the interview guide.

The results were analyzed based on the transcription of the discussion records from the focus groups, using the content analysis method. The data were independently analyzed by two specialists and for the topics that they did not agree on, the respective passages were discussed until a consensus was reached. The purpose of the analysis was to identify the participants’ assessments regarding the relevant issues related to the research theme, so that on the basis of the research results, it would be possible to complete the agenda about regulations of the sharing economy at the local level of the city of Brașov, in relation to the existing European and national situation (see Table 1).

4. Results

4.1. General Issues about Sharing Tourism in Brașov

As the participants consider, we may conclude that there is a sharing economy in Brașov in tourism. An important portion of the participants consider that the development of a sharing economy is a normal phenomenon, around the world. The participants used expressions such as “we adapt to the requirements” (9) and “we are open-minded to novelty” (10).

“Yes, it is a current trend. Tourists take it ahead of legislation. A new form that manifests itself especially in tourism and we can’t oppose it”, highlighted the representative of the Ministry of Tourism (14). Trying to understand the scale of the sharing economy in Brașov, the participants realized and stressed that there is a lack of this phenomenon in its form as the theory states. Instead, starting from the idea of a collaborative economy in Brașov tourism, large-scale business has developed—but not registered/unlicensed and non-taxed.

“Yes, we have this kind of business, but the units are not classified by standards”, highlighted the representative of the City Hall (1), in agreement with the majority of participants. In addition, a representative of one of the biggest real estate agencies said, “I know that properties, even entire guest houses are shared. We collaborate with these owners” and “Many investors offering better conditions as at the hotels have an occupancy rate of 60–80%, especially if the property is located in the historical center. There are boutique apartments at much better price asked by the hotels. The owners win, the tourists win, but room-sharing does not really exist” (2).

To support this idea, the representatives of the real estate agencies presented several examples: developers who build real estate with dozens, even hundreds, of apartments, with the purpose of introducing them into the “collaborative” tourist circuits, or individuals, especially Romanians, that live abroad in developed countries, as well as foreigners, who invest in apartments that are introduced in the touristic circuit: “Today we had a meeting with a customer buying the third apartment for this purpose”, said the agent of a real estate agency” (7).

The representatives of the registered accommodation units (hostels, hotels) pointed out that this trend is “very high”, but the “registered property owners are affected” (3) because of the unfair competition that sharing tourism exerts. According to them, the low prices that these services providers are able to sell are due to the fact that they are not taxed (they do not pay taxes on income, local taxes used for economic purposes, rescue fees, city tax, and other taxes or compulsory payments for registered accommodation). In addition, most of the providers from sharing tourism use a workforce without contracts of employment (so it is still non-taxed): “The phenomenon is at the beginning, the hotel and guest houses infrastructure is developed, and it’s pretty hard to get in, if you do not practice dumping” (8). One of the tourism specialists tried to explain the magnitude of this form of tourism by the fact that the accommodation offer is large, and it is difficult to penetrate this market as a service provider, unless you offer low prices.

4.2. Sharing Tourism and Sustainable Development

All the participants agreed that sharing tourism has many important economic benefits. Those who enjoy most of these are the owners of the rented properties and “shared” rooms and the tourists that pay a lower price, compared to traditional tourism. One of the participants, who has a long experience in tourism said that, despite this unfair competition—as considered by those who represent registered/classified accommodation units—young tourists looking for low-cost offers are at an advantage: “Sharing tourism does not lead to an increase in the number of experienced tourists, familiar with classic accommodation, but low-cost accommodation” (8), he said. He argued his claim by explaining that young tourists usually cannot afford other types of tourism.

The large number of “young and educated” tourists who visit Brașov due to the fact that accommodation prices are small, represent, in the opinion of the participants, the biggest benefit given by this form of tourism. They will share information, they will promote the town and, in the long-term, the entire Brasov community will win.

The representative of the Touristic Information Center brought other arguments, such as the fact that this type of tourist has a different behavior. If, for example, tourists from the traditional sector want to enjoy the facilities offered by a hotel, the tourists from the sharing tourism sector “they travel a lot in nature, they visit tourist sights and they are preoccupied by shopping”. Other economic benefits of sharing tourism identified by participants were “development of entrepreneurship, the creation of jobs” (13).

Regarding the benefits of sharing tourism in the socio-cultural field, most participants agreed that there are very few tourists who stay in houses or rooms “shared” with locals (houses/apartments in which the hosts are living together with the tourists) and interact with the locals, so they can provide a socio-cultural transfer. Even in the few cases where such interaction happens, it is impossible to “control” the information transmitted, so the information can subscribe to a strategy for urban development. One of the participants exemplified, presenting in a very personal manner, the way that citizens from Brașov provide information about Dracula and The Dracula Castle. The effort to control how this information is transmitted is considered useless by most participants. There were also participants who considered that the existence of platforms with information about Brașov and its culture, platforms that should be easy to use, could be beneficial.

Most of the participants agreed that most of the tourists that rent apartments/rooms through electronic platforms do not want to interact with the hosts. Even in the case of interaction, they prefer a professional attitude and they do not require much information because the virtual space offers all the information that a tourist needs. The participants consider that tourists appreciate that the reviews made by other visitors on various on-line platforms or audio-guides are sufficient for getting the proper information.

Regarding environmental protection, most of the subjects appreciate that in sharing tourism, there is a higher consumption of resources because the participants in that economy do not subscribe to a saving policy; regarding the selective collection, there are no regulations in sharing tourism. Participants also find it very difficult to provide training on collective waste collection or regarding the rational resource consumption because, in this market, operators are hard to identify. At the same time, the participants consider that owners have a direct interest in saving resources, so even unregulated, they will head in this direction.

4.3. Employment and Sharing Tourism

A similar conclusion led the question regarding the employment regime of service staff in this type of economy. Most of the participants believed that while it would be preferable for employees in sharing tourism to be trained and employed on the basis of a work contract, it is almost impossible for these issues to be “controlled”.

In addition, the employed persons are not always well trained, both in terms of specific competences and their behavior. The respondents pointed out that the personnel should be trained by the local authorities to respect the Brașov 2030 Strategy, as it was considered that the touristic development of the city should be contributed to by all the representatives of the business sector, including sharing tourism.

4.4. Licensing, Authorizing, and Classification in Sharing Tourism

Regarding licensing/authorizing this activity, most participants agreed that when this activity turns into an economic activity, it has to be licensed and it has to be taxed just like any other business. The respondents considered that the procedures of licensing are complicated, and, for the operators in the sharing economy to enter into legality, the procedures should become simple.

Representatives of the public authorities stressed that a distinction should be made between licensing/authorizing and taxing. The authorization means functioning in terms of legality, both in terms of licensing and taxation. In terms of taxation, it should be analyzed both from the perspective of income tax and of local tax and duties.

The real estate agency representative stressed that “Authorization is complicated and would discourage this type of economy” (2), considering that sharing tourism “is no longer cost effective if the authorization should be made and all taxes and fees should be paid” (2). The focus groups participants came to a consensus on the simplification of authorization procedures: “should be encouraged to authorize/license, by simplifying procedures, by reducing the necessary approvals and by lowering taxation” (5); “An easy way to find documents and information provided by the institutions for the authorization should be found. Otherwise, it is a very important reason for avoiding submitting documents for authorization. It’s hard to “convince” someone to win less just because that’s right” (9).

One of the representatives of the Tax Municipal Office raised the issue of fines that are small, so those who make consistent incomes from this type of activity can “afford” to pay them: “If the procedure were simplified and less costly it would go into legality. It would go into legality and there would be fiscal controls with higher fines” (4), he argued. Regarding the limit from which an accommodation provider should be authorized, the points of view were divergent. Whilst some participants believed that authorization and taxation should be made no matter the income and the number of rooms/apartments, some of the participants considered a limit of 10 accommodation units—so, higher than the actual regulation specifies—stressing that a large number of owners of rented apartments for tourism purposes do not know that they should go into the process of authorizing and they do not want to do that for economic reasons.

4.5. Taxation in Sharing Tourism

The representative of the Tax Department explained that “the legislation provides a differentiated tax for residential and nonresidential building, thus used for economic purposes. Those who carry out tourist activities, including renting their own homes, according to the law, they must change the destination of the building, even partially. But the procedure of changing the building destination is complicated and quite expensive—it involves even expertise costs” (11).

For example, in Brașov, in 2018, if the tax for a residential building is between 0.08% and 0.2%, at a calculated value of the building comprised between approximately 27 and 225 euro/square meter, for a non-residential building (used for touristic purposes), the owner has to pay a 1.8% tax calculated for a building value between 750 and 1000 euro/square meter. By exemplifying, for a 100 sq m building, if it is registered as a residential building, the annual tax is approx. 45 euro/year, which can be adjusted according to the rank of town and area with a coefficient of max. 2.6 and up to max. 117 euro/year; for the same building registered for non-residential (economic) purposes, the tax paid by the owner will be between 1350 and 1800 euro, which is 10 times higher. Travel service providers must also collect and pay a tax for the city promotion and a tax for the Mountain rescue unit.

The representative of the Ministry of Tourism explained that, regarding classification, the Romanian legislation was simplified, and nowadays, any unit could be classified very simply: “At the Ministry of Tourism is simple, forms are sent by post. The only cost that is have to be paid represents 45 lei (NB—approx. 10 euro)—the tax for the Trade Registry”. In addition, the classification procedure is free of charge.

Individuals who rent rooms, even though they cannot be classified, they can function legally on the basis of Common Orders 28/10.01.2012 (Ministry of Public Finances) and 22/06.01.2012 (Ministry of Regional Development and Tourism) regarding the criteria for establishing the annual income tax corresponding to a rented room for tourist purposes located in one’s own property. According to this act, renting up to five rooms from personal properties for touristic purposes for stays of minimum 24 h and maximum 30 days/year does not require a classification procedure, but the incomes are under the taxation regulations. The annual income rules are established by categories of cities, depending on the location, and they are submitted annually to the Ministry of Finance by the Ministry of Tourism.

The focus group participants considered that the role of on-line platforms should increase, with an extension on fiscal consolidation. They consider that such platforms are very important in promoting and establishing hierarchy on the market, through customer reviews that can largely replace certifications and licenses made by various state institutions. More control and accountability of platform managers could be one of the possible solutions to create a reasonable framework to ensure a balanced and appropriate environment for traditional forms and new forms of economy.

5. Discussion

The impact of sharing tourism in Brașov might be appreciated like a significant one, but the real impact is unknown. The main reason for this situation consists of the fact that a lot of the service providers are not registered, so the authorities have access to minimal data concerning this issue.

At a first impression, sharing tourism is associated with an unfair kind of competition. But it gives economic, social, and environmental benefits to service providers, to tourists, and to the city. In this respect, there is a sustained preoccupation for the sector.

This research started from the European Agenda for the Collaborative Economy Development. According to this, the EU established an assessment of some “key aspects” of regulations regarding the sharing economy to find ways to integrate them at a national level. The urban governance may improve the local development by following the European national framework, and, at the same time, by involving the sharing tourism sector at a local level. For Brașov, some priorities were highlighted:

As the participants highlighted, an important issue that affects the sharing economy in Brașov is registration of the touristic activity. As the representatives of the real estate agencies pointed out, from their practical knowledge of Brașov, there are big business developed on the idea of short-term renting (the respondent himself is involved in such business), without getting licenses/authorizations. The European studies state the fact that Romania is one of the countries with the highest openness to a sharing economy; regarding the national law, there is a simple procedure to get the license; the problems appear in the fiscal status, so the service providers are discouraged. The local authorities have a tool to follow the unregistered providers, by finding the ones that are not paying two local taxes—a tax for the city promotion, and a tax for the mountain rescue. A strategy for identifying and informing the touristic service providers should be planned, considering the fact that, as it was mentioned, a lot of them probably do not know that they have some obligation when renting apartments/rooms for tourists. Anyway, the problem is more complex than that, considering the fact that the fiscal status of the property changes at registration, so the provider is not encouraged to register, but these taxes are under the Fiscal Code provisions, so the local governance does not have enough instruments to deal with it. In fact, comparing these taxes with the taxes paid by traditional accommodation units shows that the collaborative sector is still favored.

Regarding the limit that sharing tourism becomes business, the Romanian law establishes, in a very clear way, what is that limit, so the local authorities, with the direct involvement of the Fiscal Department, are able to identify people that are doing this kind of business. The research revealed the fact that the employment status is almost impossible to control, with most of the owners being not only the beneficiaries, but also the self-employers, in their own business.

One of the most relevant discussions refers to the fiscal issues. First, there are some difficulties regarding the procedures of registering at the fiscal authorities. The procedure involves too many actors—providers, local authorities, experts in law and evaluation (NB—all the categories of stakeholders have stressed this aspect). Making the procedure easier would encourage the service providers to register. Also, despite the fact that the local taxes are low, other taxes may discourage the providers. But, there is another issue to be noticed—the fact that fines are “affordable”, so providers easily take the risk of not paying taxes. The regime of VAT is clear, so, if the provider is registered, VAT would not represent a difficulty.

In addition to the European Agenda items, some other issues might be noticed:

- Sharing tourism has two kind of impacts on urban life:

- positive impact—it contributes to the city development, as an income generator (both through paid taxes and through the development of other industries of Brașov) and as a city promoter (the reviews from the platforms are followed by other potential tourists);

- negative impact—the traditional sector has a new competitor, which is not always appreciated as a fair one.

- Sharing tourism contributes the sustainable development of the city—despite the fact that only a part of sharing tourism is registered.

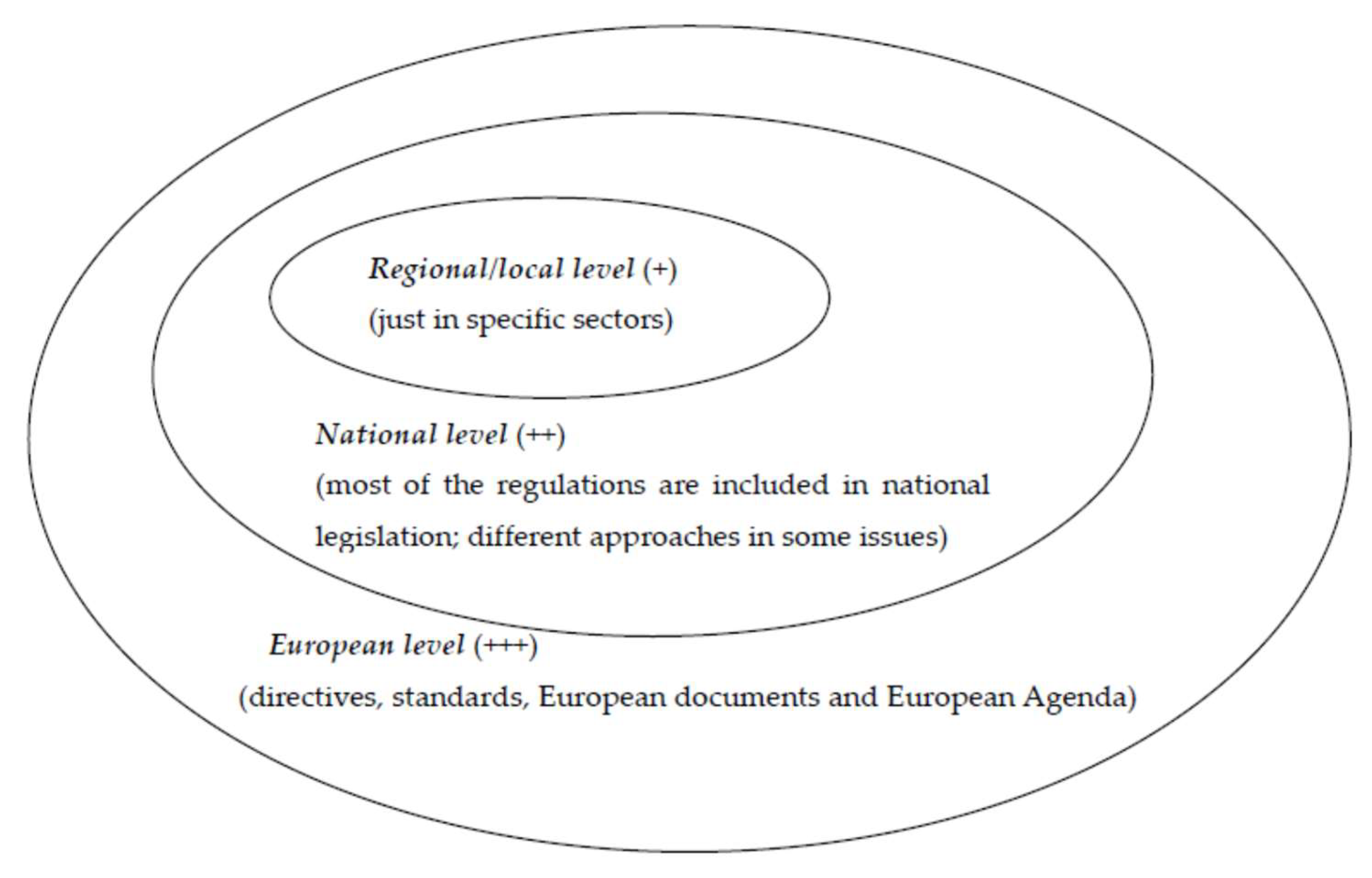

Regarding the requested levels for assuring the legal frame of the sharing economy, it emerged that this is an issue that can only be solved based on a multilevel approach, considering the fact that not all the representatives have the tools to create and implement the legal issues. Despite the fact that the theory of European governance recognizes the importance of this approach, in practice, the European legislation is differently applied in the member states, at the national level, and there is still a lack of initiative at the regional level, with only some of the sectors being under the regulation frame (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

European general regulation frame of the sharing economy. +, ++, +++—level of regulation acts.

6. Conclusions

After the secondary data analysis, it seems that the sharing economy, even though it is still in an infant stage, because of its fast growing nature, became, during the last years, a serious preoccupation for the world economy. At the global and European level, there is a framework that assures general guidelines and regulations, objectives, and strategies, in order to encourage the sustainable development of this type of economy, with a focus on maintaining a balance between the sharing economy—as a representative of the new, innovative types of economy—and the traditional forms of economy.

The main conclusion of the secondary data analysis is that, despite the general regulations assured by the international framework, and, punctually at the national level, at the regional and local level, this issue becomes a matter of local governance. Of course, under the jurisdiction of national law, and by respecting the European/global provisions about the sharing economy, at the regional level, some “key actors” can be identified.

This article is based on qualitative research with the contribution of a series of representatives of public institutions and stakeholders involved in the regulation of this sector. The main advantage of this research is the fact the respondents had the liberty to express their opinion about this subject.

The main limitation of the research is that the results cannot be generalized. However, the results can be used as a pattern for other cities in their attempts to create mechanisms of integrating new and innovative forms of economy without harming the existing business environment and by respecting the frame of sustainable development.

The research brings value from both theoretical and practical perspectives. Regarding the theoretical implications, the authors emphasize the fact that sharing tourism contributes to the sustainable development of a city, represents an income generator, and has an important contribution to promoting the city. However, sharing tourism is often viewed as unfair competition and the local governance has an important role in solving this task. The practical implications of this paper consist of presenting the framework of sharing tourism in Brasov, from the perspective of the specialists and representatives of the stakeholders involved in this field. Each part of this framework was analyzed and detailed in the previous chapter of this paper.

The authors intend to continue researching this theme, so, as a future research direction, they are taking into consideration quantitative research among tourists and touristic service providers, in order to conduct a complete analysis of the sharing economy, with a focus on tourism and sustainable development.

Author Contributions

All the authors equally contributed to this work, to the research design and analysis. Conceptualization, B.T. & G.E.; formal analysis I.B.C. & A.S.T.; methodology A.S.T.; writing, review, and editing, I.B.C. & B.T.; supervision, G.E. & J.M. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research was co-financed by Transilvania University of Brașov in a special research program—Transilvania University Scholarship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Emas, R. The Concept of Sustainable Development: Definition and Defining Principles. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5839GSDR%202015_SD_concept_definiton_rev.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2018).

- United Nation. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/42/427&Lang=E (accessed on 4 October 2018).

- Kathan, W.; Matzler, K.; Veider, V. The sharing economy: Your business model’s friend or foe? Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Kietzmann, J. Ride On! Mobility Business Models for the Sharing Economy. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daunorienė, A.; Drakšaitė, A.; Snieška, V.; Valodkienė, G. Evaluating Sustainability of Sharing Economy Business Models. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 836–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.J. The sharing economy: A pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form of neoliberal capitalism? Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.; Llosa, S. On the Difficulty to Define the Sharing Economy and Collaborative Consumption—Literature Review and Proposing a Different Approach with the Introduction of ‘Collaborative Services’. 2018. Available online: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01820276v1/document (accessed on 25 August 2018).

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhlmann, M. Collaborative consumption: Determinants of satisfaction and the likelihood of using a sharing economy option again. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 14, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. An Exploratory Study on Drivers and Deterrents of Collaborative Consumption in Travel. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Tussyadiah, I., Inversini, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjaafar, S.; Kong, G.; Li, X.; Courcoubetis, C. Peer-to-Peer Product Sharing: Implications for Ownership, Usage, and Social Welfare in the Sharing Economy. Manag. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, V.; Ambard, A.; Turner, D.; Gossman, C.; Demkova, K.; Carroll, J. A Muddle of Models of Motivation for Using Peer-to-Peer Economy Systems. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2015, Seoul, Korea, 18–23 April 2015; pp. 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Schor, J. Putting the sharing economy into perspective. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 2017, 23, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockayne, D.G. Sharing and neoliberal discourse: The economic function of sharing in the digital on-demand economy. Geoforum 2016, 77, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maselli, I.; Lenaerts, K.; Beblavy, M. Five Things We Need to Know About the On-Demand Economy. CEPS Essay, January 2016 No. 21/8. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2715450 (accessed on 25 August 2018).

- Nekaj, E.L. Forget the Sharing Economy, It’s Time for the Crowd Economy. 2014. Available online: https://www.virgin.com/entrepreneur/forget-sharing-economy-its-timecrowd-economy (accessed on 25 August 2018).

- World Economic Forum. White Paper, Collaboration in Cities: From Sharing to ‘Sharing Economy’. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/White_Paper_Collaboration_in_Cities_report_2017.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2018).

- Bani, S. Airbnb Neighbourhoods: Tourism Discourse in the Sharing Economy. Circ. Linguist. Apl. Comun. 2017, 72, 15–28. Available online: http://webs.ucm.es/info/circulo/no72/bani.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2018).

- Techopedia Definition—What does Web 2.0 mean? Available online: www.techopedia.com/definition/27960/web-10 (accessed on 7 August 2018).

- Turnsek, M.; Ladkin, A. Changing Employment in the Sharing Economy: The Case of Airbnb. Javnost-Public 2017, 24, S82–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, M.; Zysman, J. The rise of the platform economy. Issues Sci. Technol. 2016, 32, 61. Available online: http://www.brie.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Kenney-Zysman-The-Rise-of-the-Platform-Economy-Spring-2016-ISTx.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2018).

- Razli, A.I.; Jamal, A.S.; Zahari, M.S.M. Airbnb: An Overview of a New Platform for Peer to Peer Accommodation in Malaysia. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 7829–7832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Collaboration in Cities: From Sharing to ‘Sharing Economy’. Available online: www.weforum.org/whitepapers/collaboration-in-cities-from-sharing-to-sharing-economy (accessed on 12 August 2018).

- European Commission. Single Market for Services. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/single-market/services_en (accessed on 6 August 2018).

- Palos-Sanchez, P.; Correia, M. The Collaborative Economy Based Analysis of Demand: Study of Airbnb Case in Spain and Portugal. J. Theor Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 13, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to The European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and The Committee of Regions on the European Agenda for the Collaborative Economy. 2016. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/16881 (accessed on 7 August 2018).

- World Economic Forum. Future of Urban Development and Services. Available online: www.weforum.org/projects/future-of-urban-development-services (accessed on 12 August 2018).

- The Economist. Peer-to-Peer Rental. The Rise of the Sharing Economy. Available online: www.economist.com/leaders/2013/03/09/the-rise-of-the-sharing-economy (accessed on 30 August 2018).

- van der Borg, J.; Camatti, N.; Bertocchi, D.; Albarea, A. The Rise of the Sharing Economy in Tourism: Exploring Airbnb Attributes for the Veneto Region. SSRN Electron. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’ Regan, M.; Choe, J. Airbnb and cultural capitalism: Enclosure and control within the sharing economy. Anatolia 2017, 28, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioni, D. Hotel Chains and the Sharing Economy in Global Tourism (2016). SYMPHONYA Emerging Issues in Management. 2016. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2860562 (accessed on 25 August 2018).

- Chung, J.Y. Online friendships in a hospitality exchange network: A sharing economy perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 3177–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulauskaite, D.; Powell, R.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Morrison, A.M. Living Like a Local: Authentic Tourism Experiences and the Sharing Economy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birinci, H.; Berezina, K.; Cobanoglu, C. Comparing customer perceptions of hotel and peer-to-peer accommodation advantages and disadvantages. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1190–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgger, M.; Pforr, C.; Stawinoga, A.E.; Taplin, R.; Matthews, S. Who adopts the Airbnb innovation? An analysis of international visitors to Western Australia. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.; García-Palomares, J.C.; Romanillos, G.; Salas-Olmedo, M.H. The eruption of Airbnb in tourist cities: Comparing spatial patterns of hotels and peer-to-peer accommodation in Barcelona. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Vazquez, R.; Silva, J.; Santos, R.L.T. Exploiting Socio-Economic Models for Lodging Recommendation in the Sharing Economy. In Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM Conference on Recommender Systems (RECSYS’17), Como, Italy, 27–31 August 2017; pp. 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.S.; Gawer, A. The Rise of the Platform Enterprise A Global Survey. The Center for Global Enterprise. 2016. Available online: https://www.thecge.net/app/uploads/2016/01/PDF-WEB-Platform-Survey_01_12.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2018).

- Sigala, M. Market Formation in the Sharing Economy: Findings and Implications from the Sub-Economies of Airbnb. In Social Dynamics in a Systems Perspective; Barile, S., Pelicano, M., Polese, F., Eds.; New Economic Windows; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, R. Examination of motivations and attitudes of peer-to-peer users in the accommodation sharing economy. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 27, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ključnikov, A.; Krajčík, V.; Vincúrová, Z. International Sharing Economy: The Case of AirBnB in the Czech Republic. Econ. Sociol. 2018, 11, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabija, D.C.; Babut, R. An approach to sustainable development from tourists’ perspective. Empirical evidence in Romania. Amfiteatru Econ. 2013, 7, 617–633. Available online: http://www.amfiteatrueconomic.ro/RevistaDetalii_EN.aspx?Cod=53 (accessed on 12 August 2018).

- Țigu, G.; Popescu, D.; Hornoiu, R.I. Corporate Social Responsability—An European Approach through the Tourism SME’s Perspectives. Amfiteatru Econ. 2016, 18, 742–756. Available online: http://www.amfiteatrueconomic.ro/RevistaDetalii_RO.aspx?Cod=1066 (accessed on 12 August 2018).

- European Commision. Study to Monitor the Business and Regulatory Environment Affecting the Collaborative Economy in the EU. Available online: https://publication.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/79bee7ad-6d22-11e8-9483-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 25 August 2018).

- European Commision. Study on Regulations Affecting the Collaborative Short-Term Accommodation Sector in the EU. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/content/study-regulations-affecting-collaborative-short-term-accommodation-sector-eu_en (accessed on 12 August 2018).

- Direcția Regională de Statistică Brașov, Comunicat de Presa. Available online: http://www.brasov.insse.ro/turism/ (accessed on 20 August 2018). (in Romanian).

- Common Order Number 28 from 10th of January 2012 (MFP), Number 22/2012 from 6th of January 2012 (MDRT). Available online: https://codfiscal.net (accessed on 8 October 2018). (In Romanian).

- Norme Turistice. Available online: https://static.anaf.ro/static/10/Anaf/AsistentaContribuabili_r/Normeturistice2018/BrasovTur2018.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2018). (In Romanian).

- Ministerul Turismului. Lista Agențiilor de Turism Licențiate—Actualizare 24 August 2018. Available online: http://turism.gov.ro/web/autorizare-turism/ (accessed on 12 August 2018). (In Romanian)

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).