2. Literature Review

The context of global sustainable development required the framing of shared goals and adoption of common actions. Consequently, with the launch of the Millenium Development Goals (MDGs), a new stage of global cooperation on addressing sustainability related issues emerged [

2]. Further, in response to their ending agenda in 2015, a new phase of political compromise on addressing sustainability related challenges ascended when the 193 member states of the United Nations agreed on common efforts to accomplish progress in addressing social, economic, and environmental encounters in their countries [

2]. With the 17 SDGs comprising 169 targets, the stakeholders expressed their ambition to act collaboratively to achieve by 2030 the agenda for sustainable development [

3]. Therefore, the analysis and evaluation of baselines for the Sustainable Development Goals and Index became a focal theme to several scientific studies [

2,

4,

5].

Several initiatives address the evaluation of sustainability at local [

6,

7,

8,

9], regional [

7], or national [

1,

2,

5] levels. For example, Tanguay [

8] developed a selection method for Sustainable development indicators (SDI) on an urban level called SuBSelec, which is based on a total of 188 indicators retrieved from 17 related studies. The aim behind the approach was to extensively address the elements of sustainable development and to reduce the number of urban sustainable development indicators to an optimal number.

Next to this, Mascarenhas [

7] established a set of 20 local scale indicators for the Algave region in Portugal, which aim to facilitate the interaction between the local and regional scales on the monitoring process of sustainable development. The work taken up by Kawakubo et al. [

6] defined a new version of the so-called CASBEE-City (Comprehensive Assessment System for Built Environment Efficiency) instrument, developed to evaluate and monitor sustainability levels achieved by communes and cities around the world within the framework of SDG indicators and greenhouse gas emissions. The instrument was applied to 79 urban areas from 39 countries. The results reflect on the higher achievement levels of well-developed urban areas in relation to quality of life and lower achievements in terms of environmental load, whereas the least developed urban areas experience opposite outcomes under these two subjects. In a more definite perspective, Tomalty [

9], for example, developed an overall community sustainability index. The study involves 27 municipalities with over 30,000 inhabitants from Ontario, Canada and the calculation of the overall index is based on 33 indicators covering the subjects of smart growth, livability, and economic vitality. To generate a composite index for each of the above-mentioned subjects, the normalization of the collected data was performed. Recent papers demonstrate the use of the min-max method as well as the arithmetic mean calculation. For example, Nhemachena [

5] evaluated the sustainability associated to the field of agriculture for 13 sates of Southern Africa, where eight indicators within the field of agriculture were normalized based on the min-max method and an agriculture-related SDG composite index was calculated based on aggregation through the arithmetic mean. Next to this, both, the min-max and arithmetic mean methods were applied by Sachs et al. [

1] and Schmidt-Traub et al. [

2] in the calculation of the SDG index used in the sustainability appraisal of 149 countries. The study of Guijarro [

10] comes with a new weighting model in the calculation of the SDG index. Although being similar to the previous studies, the model is based on the min-max normalization method. The results show that in terms of sustainable development, from the EU’s 28 countries, the best performers are Austria and Luxemburg whereas the worst performers prove to be Greece and Romania.

Nevertheless, the question of measuring SDGs on the local level has only been addressed in few studies by using different methodological approaches. Sustainable development, for example, in a Romanian context, has been addressed by Sirbu et al. [

11] using nine indicators whereas Stănciulescu and Bulin [

12] applied 10 indicators in a timeframe of five years when comparing Romania’s and Bulgaria’s progress with the EU’s average achievements. Next to these, other recent studies on Romania that analyze sustainable development are approaching this topic from the view of the renewable energy sector [

13,

14,

15,

16], and the perspectives of sustainable transport [

17,

18] or regional well-being [

19].

Even though, from an international perspective, sustainability at the local level has been addressed by various scholars [

6,

7,

8,

9], our research remains one of the few studies that assesses progress in attaining the SDG goals on the metropolitan scale. Therefore, the applied methodology retains its relevancy not only in a Romanian context, but also applied in other international studies. Enhancing performance at the local level contributes to the attainment of achievements on higher administrative levels. Therefore, the integrated and place-based approaches became a focal point of the Europe 2020 Strategy and, consequently, addressing the urban dimension became an essential effort for the current European planning system [

20]. The current paper considers the progress of several local authorities in a Romanian metropolitan setting within the context of the SDGs and builds a metropolitan SDG Index, which is also represented on a map. The selected study area for our analysis is the Cluj Metropolitan Area (

Figure 1), which is located in the North-West development region of Romania and the heart of the historic region of Transylvania. It is situated on a surface of 1537.54 km

2 with a population of 425,592 inhabitants [

21]. It is one of the largest metropolitan areas in Romania. From a territorial administrative perspective, it is composed of the municipality of Cluj-Napoca and its adjacent 17 communes divided on two distinct functional ‘rings’ (

Figure 1) according to the intensity of their labour relations with the metropolitan core of Cluj-Napoca [

22]. The municipality has a population of 323,484 inhabitants [

21] and is situated on a surface of 1795 km

2, being one of the most important drivers of economic growth and cultural centers in Romania [

23,

24]

The metropolitan area was founded in 2008 as a response to the top-down initiative of the Romanian Government and manifestation of the growth pole concept. The main reason behind this turn was the process of Romania’s adherence to the European Union that increased the role of decentralization, with the aim to achieve balanced territorial development [

23]. Nevertheless, in several cases, the decentralized structures prove to be inefficient [

25] and the strong socio-spatial differentiation between the composing localities of the metropolitan areas might jeopardize the territorial cohesion, balanced progress [

26], and, subsequently, metropolitan-wide sustainable development. In the case of the Cluj Metropolitan area, from both economic and demographic perspectives, the new twist triggered a drive that started from the urban core towards the hinterland and led to a so called urban-rural diffusion [

27]. The functional transformations experienced within communities and the necessity to create improved connection between the urban core and rural settlements placed these development processes in a new spatial dimension. Moreover, the urgent need to interlink the human resources living in rural areas and the workplaces offered in the urban core promoted intensified harmonization between commuting and accessibility [

22], and placed urban development challenges in a new spatial and functional dimension. Consequently, there is a need to ensure that metropolitan governments increase their capacity in applying practices that increase their competitiveness [

28], review their progress [

2], and drive the inclusive development of their component localities. As part of the integrated planning process, the first integrated plan elaborated for the metropolitan area of Cluj was the Integrated Urban Development Plan (IUDP), effective for the period of 2009–2015. Nevertheless, its shortcoming was the fact that in certain initiatives, the development concentrated in the municipality, hence, by some means, development returns failed to trickle down to the adjacent communes. The second effort on the integration axes from a planning perspective was the adoption of the Integrated Urban Development Strategy (IUDS), valid for the period of 2014–2020–2030, and the Integrated Mobility Plan (IMP), which provide a framework for strategic planning and enforce trans-boundary development. Nonetheless, the fragmented governance approaches [

26], rapid and uncontrolled urban-hinterland transformations, [

27] as well as financial support based on arbitrary decisions [

29], threaten the effectiveness and fulfilment of integrated plans. The increased migration of the population in the communes directly adjacent to the municipality (the first ring communes) led to a fairly earlier development spread in these areas and slower development in the metropolitan fringe [

29]. Nevertheless, the outmigration from the center to the outskirts must be considered a natural phenomenon, which requires customized initiatives and adaptive planning [

30]. Consequently, there is a need for better consideration of the spatial characteristics, continuous measurement of progress, identification of intervention areas, and customized actions to achieve sustainable results.

4. Results and Discussion

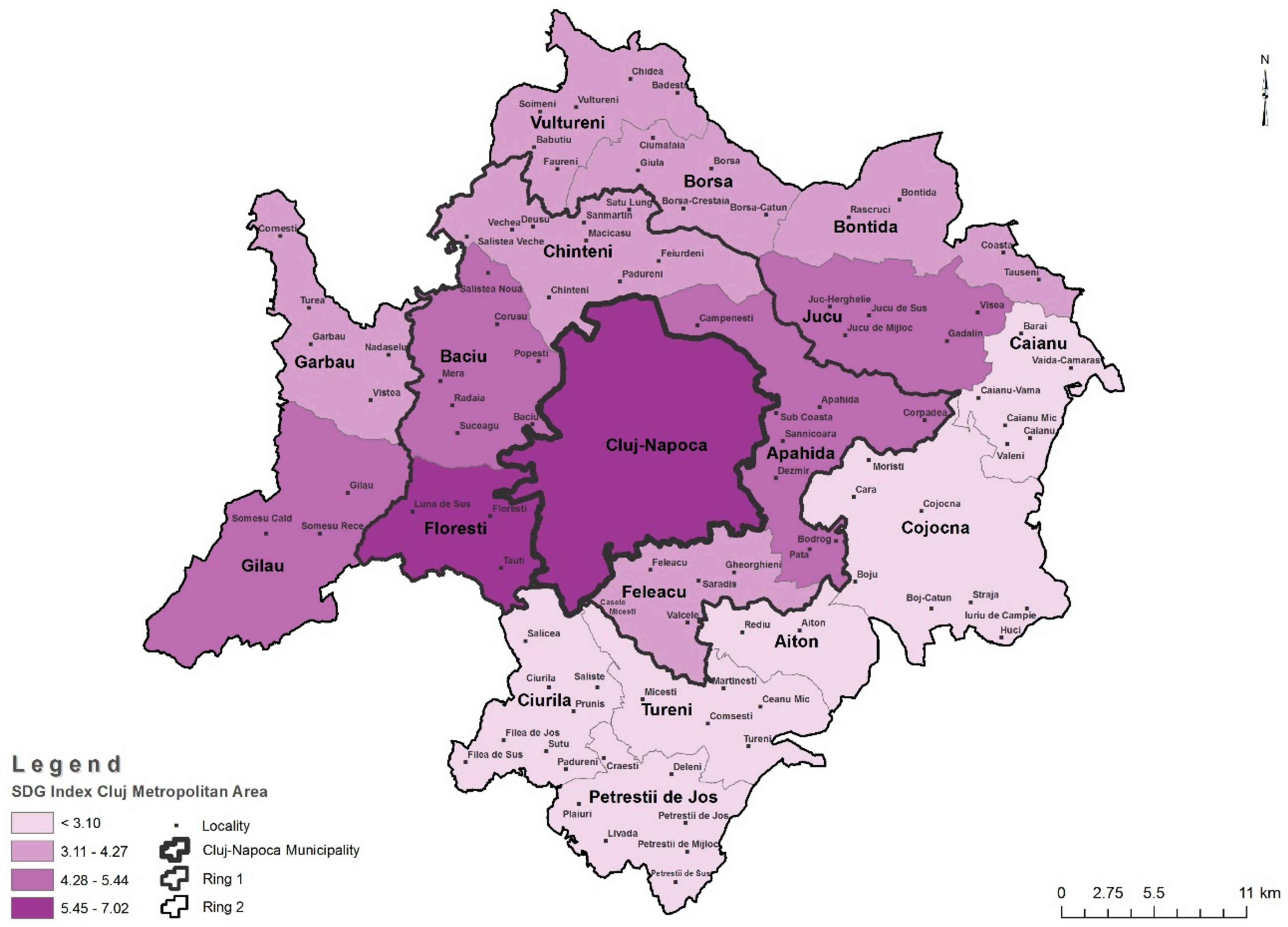

As pointed before, in our analysis, we assess the spatial expression of the 16 SDGs. To synthetize all the 36 indicators and one index into a scalable compound measure of the overall achievement of each locality and, subsequently, the CMA, we calculated and mapped the overall SDG Index for each locality respective of the CMA, as presented in

Figure 2 below.

Furthermore, the SDG Index facilitated the ranking of localities against their overall achievements and made them comparable with each other. The Dashboards (illustrated in

Appendix A), on the other hand, provide a clear and comprehensive picture about the differences in each locality’s performance within the individual SDGs and help identify imbalances in their development path by comparing their performance across the individual sustainable development goals. Next to this, they also serve to assist in identifying the implementation priorities in each of the CMA’s localities. As shown in

Figure 2, based on the SDG Index, the municipality of Cluj-Napoca ranked first from the Cluj Metropolitan Area having covered 7.02% of the distance towards the maximum result of 10.00 across the SDGs. Next to the municipality, the first ring locality of Florești is the only one that also managed to make it to the first level category (indicated by the green band in

Appendix A) with about a 10% lower score than Cluj-Napoca. The second level category (indicated by yellow in

Appendix A) is composed by two of the first ring localities, Baciu and Apahida, respectively, and two of the second ring localities, Gilău and Jucu. Consequently, the remaining two localities of the first ring communes of Feleacu and Chinteni only manage to integrate in the third level category (indicated with the orange band in

Appendix A), yet, the latter one reaches results slightly lower than the second ring commune of Bonțida. Next to this, the first ring locality of Chinteni falls 5% behind the metropolitan average of 4.04. The remaining localities from the third level category achieving results within the orange band are the second ring communes of Borșa, Gârbău, and Vultureni, falling with about 10% below the metropolitan average score. Meanwhile, six out of the 18 analysed localities remain in the red band. This fourth level category is led by Tureni followed by Petreștii de Jos, Ciurila, Căianu, Aiton, and the last in ranking, Cojocna. The localities of the red band are at least 6.90% of the distance away from the maximum score (10.00) and 7.82% at the most. Consequently, a clear divergence can be observed in the accomplishment levels and feasibility of localities mainly considered to be part of the functional urban area (including, in our case, the communes of Florești, Baciu, Apahida, Gilău, and Jucu) and the remaining communes of the metropolitan area with lower provision of utility and transport services. Therefore, in line with the Integrated Urban Development Strategy (2014–2020–2030) [

37], the administrative capacity should be expanded and strengthened at a metropolitan scale to ensure progress in achieving a more coherent development and, consequently, better progress of the CMA in delivering the SDG goals. Furthermore, a deliberate amalgamation of legislative and incentive frameworks should be enforced to stimulate the preservation and management of the ecosystem and transition to more inclusive policies and initiatives.

As illustrated in

Appendix A, the SDG Dashboards show that even if the municipality manages to achieve good performance in most of the areas, it still faces great challenges in terms of peace and justice and difficulties under the goal of zero hunger and environmental protection. Similar areas present challenges to Florești as well (the only commune entering the green band interval) as it enters the red band category in terms of environmental protection and partnerships with reduced progress in promoting inclusive societies. Consequently, besides their close results, the two best performing localities of the metropolitan area face fewer, but similar, and imperative challenges in addressing environmental protection, and promoting peaceful and inclusive societies as well as strengthening their involvement in encouraging partnership development, to achieve the goals of sustainable growth. Overall, the outcomes highlight the need for paying greater attention to the management and integration of green areas, but also improving communication and cooperation between the public and private sectors. Next to this, the local plans and strategies should ensure that increased attention is given to initiatives addressing issues related to management and conservation of green infrastructure and incentive structures are developed for inclusive and cooperative actions.

Similarity in progress can be seen also within the second category level communes (Baciu, Apahida, Gilău, and Jucu), and even if their ‘green zones’ are slightly more or similar to the previous two, their achievements are mostly situated in the yellow or orange band. They tend to face similar challenges as the municipality and Florești in terms of reducing environmental degradation, but face greater encounters in ensuring healthy well-being, ending poverty, and promoting inclusive societies. Next to this, under the 17th goal of strengthened partnership, the second ring commune, Jucu, is the only commune that achieves progress by integrating itself in the green band, and the second ring commune of Gilău has the same results in terms of climate change. The consolidation of the green-blue network remains a priority action at the metropolitan level as expressed by the IUDS (2014–2010–2030) [

37]. Nevertheless, the challenge is stronger for the communes that experienced increased urbanization patterns and faced substantial load of real estate developments (Florești, Baciu, Apahida), and lower for those having a more rural nature. Ending poverty, however, remains a persistent claim for a higher share of localities, and should receive greater policy attention and mobilization of resources to build resilience and reduce vulnerability of those in need.

The third category level localities show substantial differences in their performance within the SD goals. The second ring communes of Borșa, Gârbău, and Vultureni have the most of the ‘red zones’, and, at the same time, are the worst performers of their category level. The most important challenge of these third level category localities is ending poverty in all its forms. Next to this, the ninth SD goal is also a theme that reflects on the lack of innovation, poor infrastructure, and deficient industrialization in these communes and calls for remedies. Some localities, notably, Chinteni, Borșa, and Vultureni, perform quite well under the goal of climate change, yet, Bonțida and Gârbău necessitate more attention under this theme. Further, mostly Vultureni, but, at a certain level, the remaining second ring localities of this category (Bonțida, Borșa, and Gârbău), require the increase of resilient and inclusive practices. Consequently, a critique might be directed towards the Integrated Urban Development Strategy in following the guidelines developed under its integrative nature. The results show that, even if the IUDS as well as the IMP contain an important focus on the provision of metropolitan-wide public transport, there is still a persistent need for more efforts in the planning practice for greater integration of service delivery, on the one hand, and improvement of food provision, on the other.

The fourth level category, similar to the previous category, presents the greatest challenges under the first goal of ending poverty, where all of the component localities achieve scores within the red band. A worse performance is shown under the goals of quality education and lifelong learning, access to water and sanitation facilities, and lack of economic growth. Therefore, substantial progress is awaited to be done by these localities in ensuring access to basic infrastructure, increasing investments in education, actions in attracting innovation, increasing social inclusion, and creating employment opportunities. As reflected by the dashboards, deficiencies are also present in terms of gender equality as well as environmental protection. Even if the communes of Aiton and Ciurila have the highest number of red band challenges, the furthest away from the highest score of the metropolitan area is Cojocna, as it has no yellow nor green band achievements under the SD goals. Therefore, even though the existent integrated strategies do cover objectives that address current and essential goals, the challenges identified through the study indicate the need for greater policy harmonization, more targeted interventions, and more emphasis on the disclosure of the progress already achieved to attain more efficient advancement in following the SDGs.

To examine the existence and the extent of a relationship between the two indexes that we had available, we correlated the SDG Index with the LHDI, the composite measure of three major themes of health, education, and income. As shown in

Figure 3, there is strong evidence from the scatter diagram that a strong, positive relationship (r = 0.92) exists between the two variables, which leads us to think that those localities that make significant investments in health and education are more likely to perform better on the SDG Index as well. Further, as indicated by the formula, approximately 85% of the variation in the SDG Index can be attributed to the variation in expenditures on health, education, and the income outcomes.

The results highlight the deliberate consequences generated by the inexistence of express policies involving the SDGs defined under the Agenda 2030 on local and regional levels of the Romanian policy-making process. Therefore, it is beyond the scope of this study to assess the institutional profiles for the implementation of local policies aimed at the achievement of the SDGs established by the UN. As previously mentioned, the main local policy documents relevant for the SDGs are the IUDS 2009–2015, continued by the Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan 2016–2020, both developed as part of local public administration efforts to attract EU funds under the Regional Operational Programme.

This implicitly reinforces the premise that the local public administration remains the main local institutional actor involved indirectly in the achievement of UN SDGs. Under such circumstances, we assume that a horizontal approach comes into play, where an organization-centric approach prevails over the vertical, or product-centric, approach. At the national level, the Romanian National Strategy of Sustainable Development was adopted in the current year, in line with the UN SDGs, but, currently, it is still unclear how the government will proceed with its implementation. However, poor coordination, as a characteristic of the Romanian planning system, brings along a strong top-down approach and a weak involvement of local actors in the establishment of development priorities.

5. Conclusions

The paper established a baseline investigation of the SDGs in a metropolitan setting. The methods involved a normalization, aggregation, and mapping process. Through this methodological framework, the component localities of the metropolitan area were ranked depending on their progress to achieve the SDGs. Even though the analysis faced limitations, especially in terms of gathering statistical data, the paper gives a starting point to assess the SDGs on the local level. The main shortcomings consisted of the fact that the analysis is based on data available strictly on the local level, and, due to this limitation, the number of indicators used within the examination of each separate SDG goal varies depending on their availability. However, we are confident that despite of the above-mentioned limitation, significant parts of our methodology, such as data normalization, aggregation, and, especially, the visualization techniques, can be widely applied in other spatial contexts as well.

The findings show that that urban core—the municipality of Cluj-Napoca—stands the closest to the maximum score of 10.00 by covering 7.02% of this distance. This score is slightly lower than the national achievement of 7.41 [

1], yet, supports the results of several studies mentioned in the literature review [

23,

26,

27,

29], which found that on the metropolitan level, the urban core is the most developed and, according to our analysis, has the highest progress level in achieving sustainable development. The municipality is followed by three communes from the first ring (Florești, Baciu, Apahida) and two localities of the second ring (Gilău and Jucu), showing that there is a vertical (west-east) progress visible in the CMA in terms of achieving the SD goals. Consequently, sustainable development progress is visible not only in the first ring communes, but also managed to reach out to the second ring communes as well. Nevertheless, localities on the western part of the municipality perform better in the SDGs, an outcome that can strongly correlate with the better development level of these communes that corresponds with higher accessibility to road infrastructure as their territory has access to the motorway and to a European road. Even more, this pattern is also visible on the eastern side of the municipality where the only technological park is located outside the municipality’s administrative boundary. Consequently, according to the findings, in concordance with the vertical territorial development, a pattern of sustainable progress can be seen on the west-east axis of the metropolitan area. Even yet, the best performing localities face greater challenges in terms of environmental protection, security, and inclusive approaches. On the opposite side, the worst performing localities have better progress within these areas. However, the fact that under the ‘no poverty’ SDG, only 12 communes integrate in the red band raises major concerns. Next to this, as out of the 18 analyzed localities, two localities manage to integrate in the green band and six in the red band, the metropolitan average score of 4.04 demands firm and extensive efforts to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. The spatial-functional inequalities and economic vulnerability between the first and second ring communes of the municipality present concerns and claims greater attention from their governments in reviewing progress on the SDGs. Our main findings are relevant for similar institutional contexts characterized by low coordination in the setting of spatial policy goals among national and local level actors. As such, it can serve as a benchmarking tool for metropolitan areas where economic priorities are prevailing over social or environmental aspects. As this is the first study in Romania that measures SDG’s on the local level, it is essential for similar studies to be performed not only on local, but also regional and national levels as well. Consequently, we also appointed future efforts towards extending our analysis on a greater scale and overcoming data limitations with the inclusion of a larger set of indicators to permit a wider and more precise application of the methodology set out in this paper.