1. Introduction

The provision of daylight in heritage buildings is rarely considered adequate in terms of responding to contemporary standards issued by international institutions and which have been wrongly based on Daylight Factor (DF) or climate-based daylight modelling (CBDM) [

1]. Therefore, daylighting levels afforded by the original daylighting strategy in heritage buildings are rarely maintained as an intrinsic heritage experiential value in the rehabilitation or re-use of these buildings. In the context of public bathhouses (hammams), daylight provision is frequently done from the roof space. A single oculus at the centre of a dome is a feature that is commonly found in the architecture of large Roman public bathhouses as illustrated in Pompeii’s Roman baths [

2].

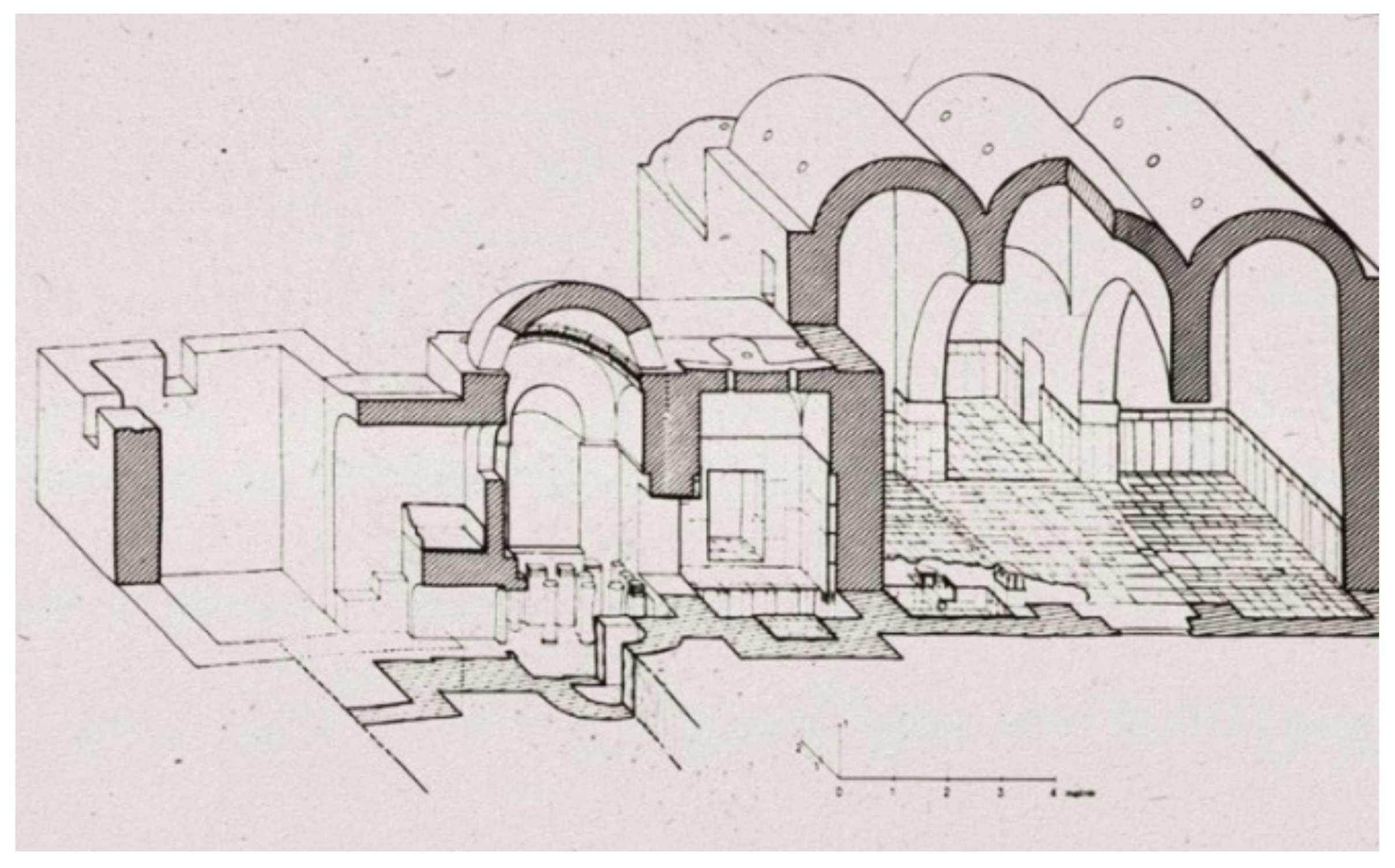

The decline of the Roman and Byzantine public bath institution in the West was followed by the development and proliferation, during the early Islamic era, of small public baths, reminiscent of the Roman baths known as balnea. These baths feature three successive bathing rooms of increasing temperature, as well as the underfloor heating system known as hypocaust, both were maintained in the architecture of Islamic hammams. However, daylighting provision was replaced by a number of small oculi, pierced in the vaults and domes of the hammam roof, becoming a distinctive characteristic of hammam buildings. This architectural feature can be seen in two early Islamic baths: Hammam Qusayr Amra, an 8th Century structure [

3] in the Jordanian desert (

Figure 1) and in Hammam Aghmat, an 11th Century Almoravid structure [

4] excavated in Aghmat, 30 kilometres South East of Marrakech in Morocco [

4,

5]. The Aghmat hammam [

6] displays rows of circular openings or oculi in the three vaults covering the cold, warm and hot rooms (

Figure 2)

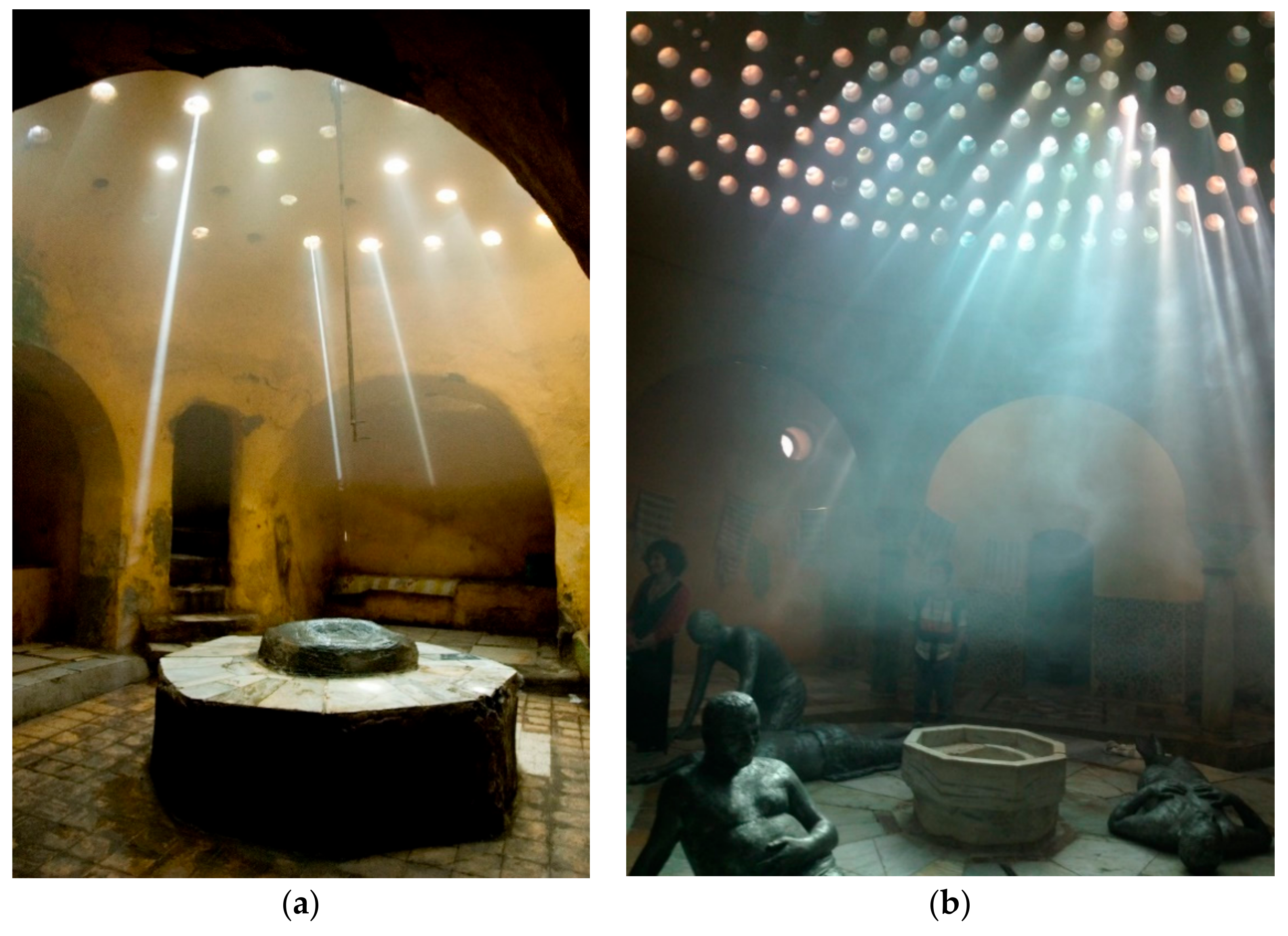

. Such a configuration will continue unchanged in the architecture of Moroccan and Andalusian hammams for many centuries onwards [

7,

8,

9]. The small circular piercings of 18 to 25 cm in diameter, located in the vaults and domes of the hammam roof are capped with blown glass bells. These allow shafts of daylight and sunlight to penetrate into the bathing spaces, cutting through the thick steam and creating different atmospheres at different times of the day. They constitute one of the unique and authentic experiential qualities of hammam buildings as illustrated in the case of one Mamluk and one Ottoman hammam (

Figure 3a,b). Known in Arabic as little moons “Qamariyyat” or little suns “Shamsiyyat”, they make a clear connection between the bather and the changing sunlight conditions of the sky. They also allow low levels of daylight into the steamy bathing spaces, hence maintaining some level of visual privacy, bearing in mind the strict religious codes governing nudity and gazing at another bathers’ body. The act of washing one’s body is indeed not a task that requires high levels of daylight, however, the manipulation of daylight in hammam spaces is believed to be highly linked to cultural and spiritual norms. It is argued in this paper that the vernacular daylighting system in hammams constitutes an intrinsic part of the heritage value and authenticity of this building type that needs to be fully understood in order to be properly rehabilitated in existing heritage structures and carefully reintroduced in the architecture of contemporary hammams in Morocco and beyond.

Existing studies on hammam daylighting systems are few and far apart. The most recent studies focus on Ottoman hammams that have lost their original function. This is the case of the study conducted by Al Maiyah et al. [

10] which rightly argue the importance of understanding the daylighting system in vernacular buildings, as this is rarely considered as a key feature worth preserving as part of adaptive reuse strategies of heritage buildings. The study focuses on how to maintain the original daylighting conditions in the hot room of the Demirci hammam in Bursa, while allowing it to function as a museum or an art gallery; the hot room being the only surviving part of this Ottoman structure. The main concern is to establish how to reuse the existing vernacular daylighting system without exposing the exhibited artefacts to levels of light that are likely to be damaging. Measurements were made to validate a simulation modelling tool, Radiance, used with a digital model of the building produced using Integrated Environmental Solutions (IES) software. The aim was to develop an understanding of the behaviour of daylight in this Ottoman hammam hot room during a whole year and determine the most appropriate spaces for placing museum or art gallery exhibits. The study highlights that the average monthly illuminance level on the South wall of the hot room remains under 140 lx in the summer months in Bursa-Turkey (Latitude: 40°11′44″ N Longitude: 29°03′36″). Although this study rightly argues the need to avoid relying solely on lighting standards for the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings, and work with the existing lighting qualities of the spaces in a vernacular hammam, it does not provide an understanding of the nature of the hammam vernacular daylighting system in all the bathing spaces as it concentrates on analysing one main redundant space.

Another study focuses on investigating the vernacular daylight provision in seven still surviving Ottoman hammams in the city of Thessaloniki in Greece [

11]. Measurements of daylight levels were, however, conducted in one case study building only, the Bey Hammam, a 15th Century twin structure used as a cultural centre was selected for recording daylight levels under different sky conditions in March 2008. The results of these measurements are presented graphically on the plan of the building with illumination levels plotted on a grey scale, ranging from 0 lx to 120 lx at a step of 10 lx [

10]. Measurements were made using a lux meter at different points of the three bathing spaces and were carried out during a single day. This study indicates a clear correlation between the intensity of daylight, the type of activities carried out in the spaces and the level of visual privacy they require. The central spaces under the domes received the most light (due to the large number of oculi found in the domes of Ottoman hammams). This is the case of the central marble table in the hot room (the main shared space in Ottoman baths), whereas the peripheral spaces used for individual washing have much lower levels of daylight, indicating a clear correlation between the intensity of daylight and the level of privacy required by the bathers.

It is clear that the al Maiyah [

10] and Tsikadoulaki et al. [

11] studies focused on a single case study of Ottoman hammams that have lost their original function: One in Bursa, (Turkey) the other one in Thessaloniki (Greece). In both studies, daylight measurements, limited in time and space, were made in redundant structures without the steam conditions typical of a working hammam. Furthermore, all case study buildings where daylight levels were measured focus on a single bathing space, usually the hot room. However, it is clear from these studies that daylight levels in Ottoman hammam bathing spaces are relatively low and are in most cases below 140 lx as one moves away from the central domed part of the hot room.

This low level of daylighting in hammam bathing spaces is also confirmed by an earlier study carried out by Mahdawi and Orehounig [

12,

13] in the context of an EU-funded research project (HAMMAM 2008). Mahdawi and Orehounig collected data on indoor environmental (thermal) conditions and outdoor microclimatic conditions in the immediate vicinity of one traditional hammam in each of Egypt, Turkey, Morocco, Syria, and Algeria over a period of one year. Horizontal illuminance was measured (at one metre from the floor) at a single point in the centre of the different bathing spaces of the five case-study hammams of Cairo, Ankara, Fez, Damascus and Constantine. These measurements are of indicative character only and not reliable as they were carried out at different seasons in each of the five hammams and under different sky conditions in different geographies. Furthermore, measurements were made in conditions where the vernacular daylighting system was either in a poor state of repair or completely redundant and did not exclude the contribution of electric lighting at the time of the measurements. However, the results of horizontal illuminance measurements clearly indicate consistently low levels of lighting (mostly below 100 lx) in the five case study buildings of different historic eras and geographical locations. These measurements present however a number of limitations as they do not link to outdoor sky conditions at the time of the measurements and are not directly comparable. Furthermore, they fail to convey a clear understanding of the hammam daylighting levels afforded by the vernacular oculi system. Despite their limitations, it is clear from these previous studies that daylight levels in the bathing spaces of hammam case-studies located in different geographies (north and south of the Mediterranean) are generally low, varying between 50 and 150 lx.

This literature review has revealed that there have been no studies so far that attempt to develop an understanding of daylight levels in all the bathing spaces of heritage hammams under working steam conditions. Measurements of daylight levels in working heritage hammams where the vernacular daylighting system is still in operation, or has been fully restored, are completely non-existent. The lack of such studies makes it difficult to specify the vernacular hammam natural lighting for hammam rehabilitation purposes and for the design of new built structures that aim to create an authentic daylighting hammam experience. This is needed in all of the Maghreb countries of North Africa where the hammam tradition is still alive. Morocco is where the largest number of working heritage hammams are found and where housing planning regulations dictates the inclusion of a hammam facility in every new residential neighbourhood [

14]. It is estimated by the Moroccan federation of hammam managers, that Morocco has more than 12,000 operating hammams, however, it is very likely that the number is much higher as there have never been a systematic national census for hammams. These operate day and night and tend to rely on electric lighting during daylight hours because of their redundant vernacular daylighting system or their poorly designed daylight provision. No studies have been carried out so far to develop an understanding of the hammam vernacular daylighting strategy and the unique spatial experiential qualities it provides. This paper provides a timely and much needed historical and architectural understanding of the hammam vernacular daylighting strategies that embed tacit cultural and social norms for visual privacy and spiritual connection to the sky. In order to do so, the following methodology was adopted.

2. Materials and Methods

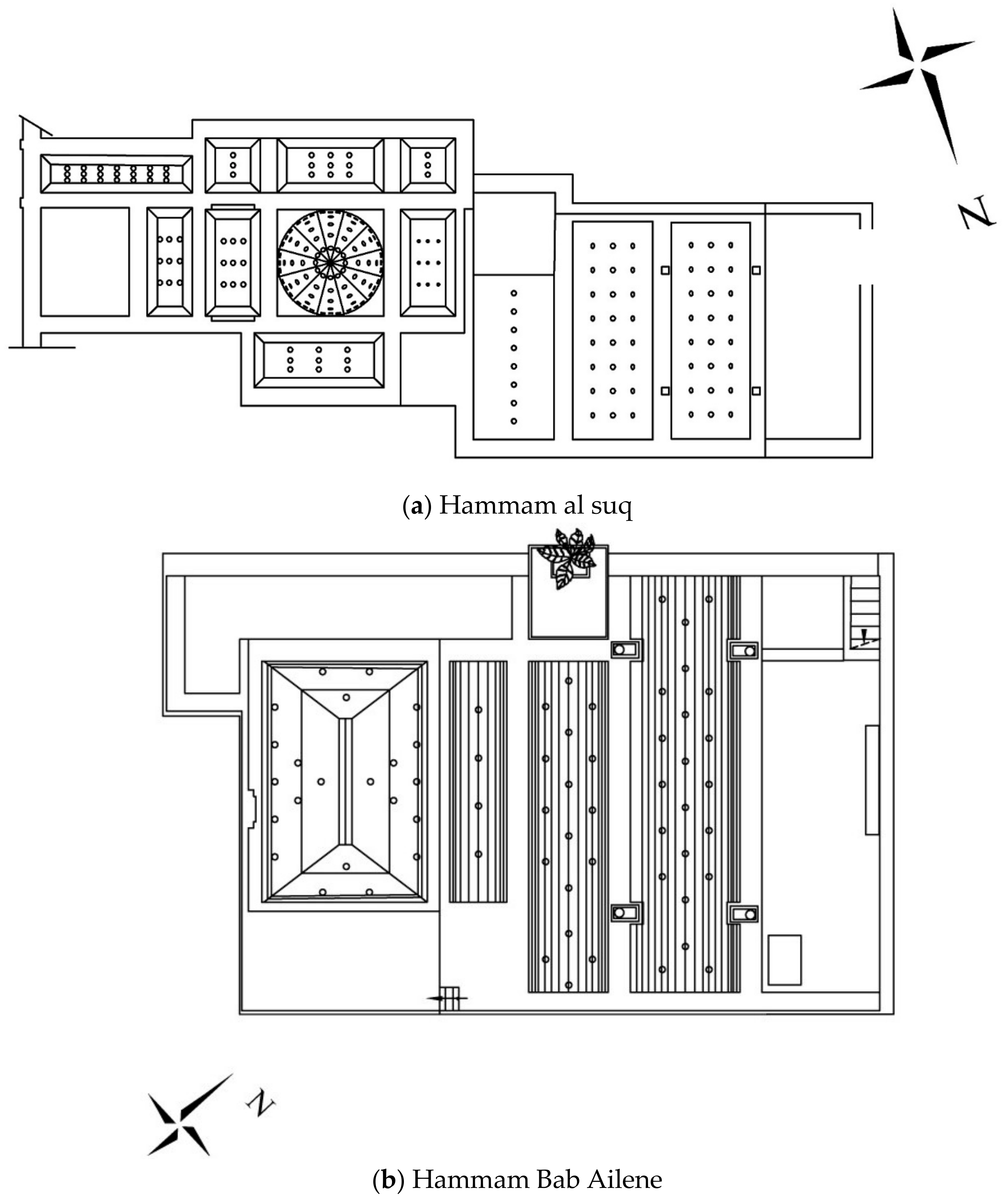

A representative sample of heritage hammams from different historical periods was selected in the old city of Marrakech. A total of 13 still functioning heritage hammams out of a total of fifteen were surveyed and recorded for the first time by the author, allowing the production of their plans, sections and elevations, as well as their roof plans and a photographic record of their various spaces (see

Table 1 and

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). More recently built hammams were deliberately excluded as the focus of this study is on the original vernacular daylighting system in heritage structures. The examined sample of hammams represents 90% of the total number of heritage hammams, located in every residential neighbourhood, within the proximity of small or large mosques inside the UNESCO world heritage intra-muros urban fabric of the city of Marrakech.

In order to establish a clear understanding of the hammam vernacular daylighting system, the following methodological steps have been followed:

- Step 1:

Architectural analyses of heritage hammam roof plans with their oculi number, location and configuration

The plans and roof openings of the 13 hammams, documented during field work in Marrakech, are systematically analysed to establish whether there are recurrent patterns in the number, location and configuration of roof openings (oculi). The aim of such analyses is to identify any tacit rules that are applied for the configuration of the Moroccan hammam vernacular daylighting strategy.

- Step 2:

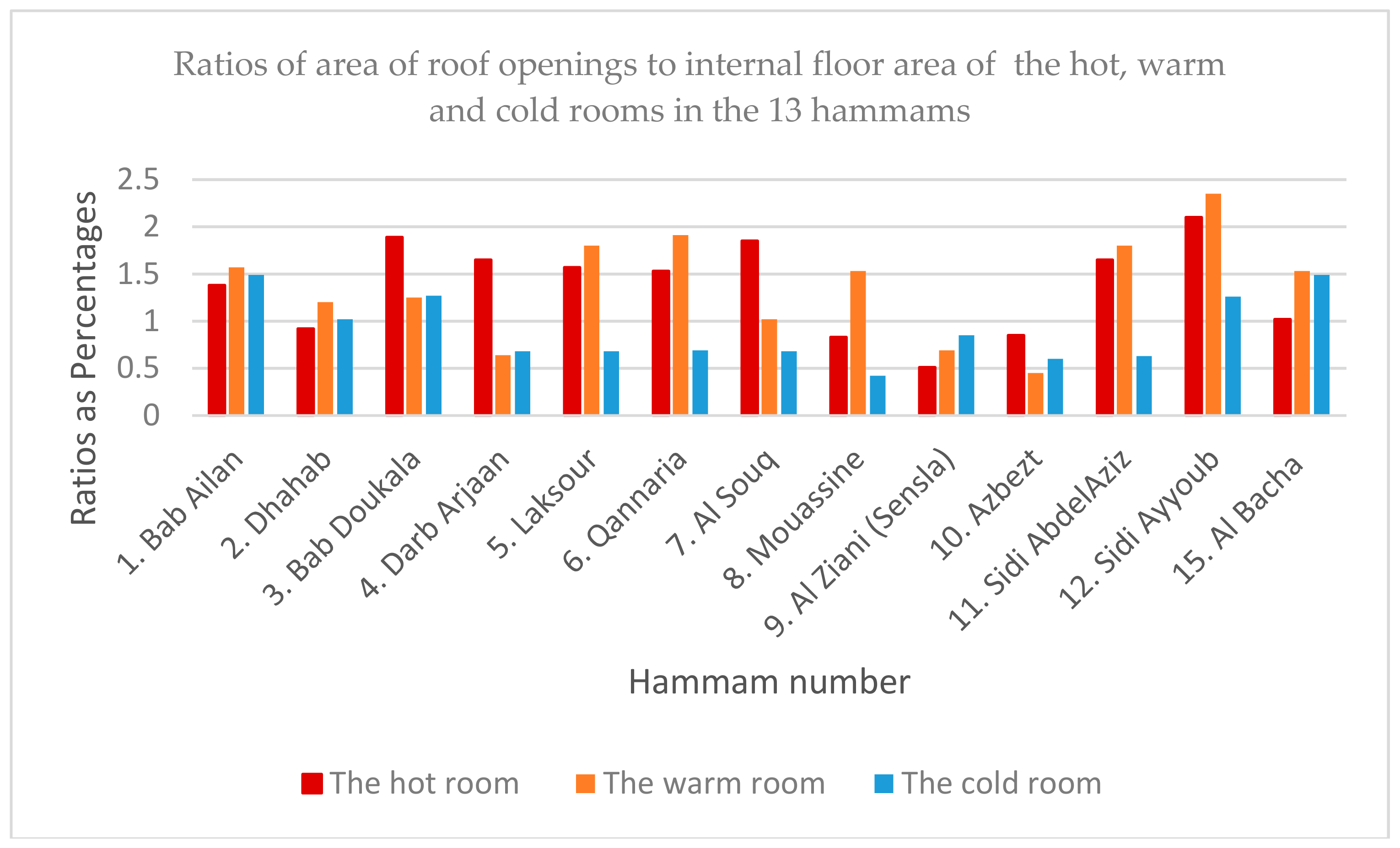

Analyses of ratios of total roof openings area over internal floor area in each the three bathing spaces of the 13 surveyed hammams

The calculation of the percentage of the total area of roof openings for each bathing space in relation to its internal floor area will reveal whether there are any recurrent ratios and whether there any variations between the cold, warm and hot rooms. This is achieved through the comparison of these ratios in the 13 investigated historic structures. This analysis also allows for the extraction of any underlying tacit rules that can inform both the rehabilitation of existing heritage structures and the design of future new hammams.

- Step 3:

Measurement of horizontal illuminance afforded by the vernacular daylighting system after its rehabilitation in a working heritage hammam

A working heritage hammam, presenting a vernacular lighting configuration of roof oculi over its bathing spaces, has been selected in order to restore the blown glass caps that originally covered the roof openings and carry out measurements of daylight levels afforded by the system in each of the three bathing spaces under working conditions. Water resistant HOBO pendant data loggers for temperature (range of −20 °C to 70 °C) and light (range of 0 to 320,000 lx) were chosen due to their discreet small size and their ease of installation in working hammam spaces with high levels of humidity [

15].

They were installed at similar and comparable locations in each of the three retrofitted bathing spaces (of similar size, colour and texture and hence similar reflectance) and on the roofs to record outdoor horizontal illuminance under open sky conditions. The data loggers were placed on the south facing parallel walls of each of the three bathing spaces and at a height of two metres from the floor (away from the bathers), allowing for comparable points of measurements. All data loggers were synchronised to measure horizontal illuminance continuously every 20 min in July, August and September of 2016. This allowed for three measurements per hour for three months which is sufficient to establish the levels of horizontal illuminance falling at similar points in each of the three similar hammam bathing spaces during the summer season of 2016.

4. Discussion

Heritage public bathhouses (hammams) of North African Maghreb cities continue to provide an affordable hygiene and well-being facility for their residents. This is particularly the case in Morocco which has the largest number of heritage hammams. It is estimated that there are at least 12,000 hammams operating in Morocco. However, this number is likely to be much higher as new hammams are being built in every single new residential neighbourhood and no recent statistics are available to date. As hammams operate day and night, their electricity bill for lighting the building constitutes 25% of their energy consumption, the remaining 75% are for water and building heating [

17]. The reintroduction of daylight into the bathing spaces is therefore estimated to reduce energy consumption by at least 12.5% (half the time is at night) and create healthier environments for both bathers and hammam workers.

The repair of the vernacular lighting system in heritage hammams of all historic urban centres in Morocco and in other North African cities can have a cumulative effect on reducing CO2 emissions and increase users’ well-being as well as revive the glass blowing crafts using recycled glass for the production of oculi glass caps. Furthermore, its adoption and adaptation to contemporary hammam projects can achieve higher levels of horizontal illuminance by increasing the number of roof oculi in the design of new structures in order to meet contemporary expectations of visual comfort from the users while maintaining architectural and cultural authenticity. Bathers, however, lack experience of the original luminous environment and their expectation of higher levels of illuminance has been reported through discussions with the manager of hammam Rjafalla. Although, bathers and staff were happy to see more daylight in the bathing spaces after the rehabilitation of the vernacular system, and commented positively about it, they still expected additional electric lighting to be used, particularly at the end of the summer months. The cultural and religious norms relating to nudity and visual privacy still apply to some extent in the use of the bathing spaces, although they are not always adhered to.

Despite the limitations of previous studies on hammam daylighting in other geographies, it is clear from the results of this study that the horizontal levels recorded in the present case study fall far below those measured in Ottoman hammams where the number of oculi in the roof is much higher than those found in Moroccan hammams.

Moroccan hammams fall under the umbrella of the Ministry of Habous and Religious Affairs (who own the majority of the heritage structures) and the Ministry of Culture and Traditional Crafts. Serious attempts have been made to reduce wood consumption in hammam furnaces to reduce CO

2 emissions, particularly after the COP 22 event held in Marrakech in 2016. However, the reduction of electricity consumption through the reintroduction of daylighting has not been considered. It has also been omitted by a study conducted by the Ministry of Culture and Moroccan Crafts aimed at establishing benchmarks of what constitutes an authentic Moroccan hammam [

18]. Furthermore, the integration of bespoke off-grid LED solar powered lighting within the vernacular daylighting system for night illumination, as developed by the author in 2015, can lead to a highly sustainable hybrid innovative solution [

17].

5. Conclusions

This paper has provided the first systematic study of the vernacular daylighting provision in Moroccan heritage public bathhouses (hammams). It combines historical and architectural analyses of a representative sample of 13 working heritage structures to reveal tacit rules underlying the number, location and configuration of roof oculi. These are then restored in a working hammam to establish the first benchmark for levels of horizontal illuminance afforded by the vernacular system in the bathing spaces under real working conditions. The results reveal a recurrent pattern of oculi number and configuration consisting of one to three rows of eight circular openings (of 18 to 20 cm in diameter) arranged along the roof vaults covering the bathing spaces.

The total area of roof openings for each bathing space was found to rarely exceed two percent of its internal floor area. Measurements of horizontal illuminance on the roof of sky conditions, as well as that of inside the bathing spaces, were carried out continuously and simultaneously in July, August and September of 2016 at 20 min intervals and at comparable locations. This has resulted in real time values, allowing for the calculation of daylight factor under real changing sky conditions. The results of horizontal illuminance measurements indicate that maximum levels are reached between 12:00 and 14:00 when the sun is high in the sky, but never exceeded 60 lx. The impact of the saturated air humidity on the daylight factor is evident in the hot room where the highest levels of DF are registered but suddenly decrease below that of the cold room as the air humidity levels reach almost 100%. Levels of horizontal illuminance are generally much lower than those recorded in previous studies in Ottoman baths and remain well below 60 lx as compared to 100 or 150 lx recorded in Ottoman hammams. Low levels of daylight are therefore a genuine experiential quality of Moroccan hammams afforded by small oculi in the vaults and domes of the bathing spaces.

This paper has provided a new understanding of the experienced luminous environment afforded by the vernacular daylighting system in Moroccan hammams and established the first benchmark for its rehabilitation in heritage structures and its future integration in new Moroccan hammams. Further studies are needed to investigate bather’s sensorial experiences of heritage hammams daylighting ambiences to understand elements of comfort that are outside the norms of numerical quantification of light. As argued by Tregenza and Marjaldevic [

19] in their review of half a century of research on daylighting, there are still important questions which fifty years of study have not fully answered: What are the criteria of good daylighting? What should be the central aim of the designer? What regulations or standards are required? “Describing lighting only in terms of illuminance is equivalent to describing music in terms of sound pressure level” [

20]. As Bille and Sørensen [

20] argue, light works as a significant constituent of experience. In their introduction to

an anthropology of luminosity, they coin the term

lightscape and highlight that “

by introducing an anthropology of luminosity; an examination of how light is used socially to illuminate places, people and things, and hence affect the experiences and materiality of these, in culturally specific ways.” From a phenomenological point of view, Merleau-Ponty [

21] argues that “

we do not so much see light as we see in it.”

Further research is needed to carry out wider measurements of illuminance as experienced and perceived by building users, combining real time measurements with recordings of users’ space use and reactions during a whole bathing session in a working rehabilitated heritage hammam.

This paper opens up new avenues for further research based on the innovative combination of historical, architectural, building science research and environmental psychology methodologies to reveal tacit rules underlying the luminous environment of heritage buildings, as well as their perceived experimental qualities, in order to provide benchmarks for the rehabilitation of original luminous environment and their reinterpretation in contemporary designs.