Barriers to Implementing Pro-Cycling Policies: A Case Study of Hamburg

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Policies to Promote Cycling

2.2. Barriers to Implementing Sustainable Transport Policy

2.3. Barriers to Implementing Pro-Cycling Policy

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Cycling Trends and Policies in Hamburg

4.2. Barriers to Implementing Pro-Cycling Policies in Hamburg

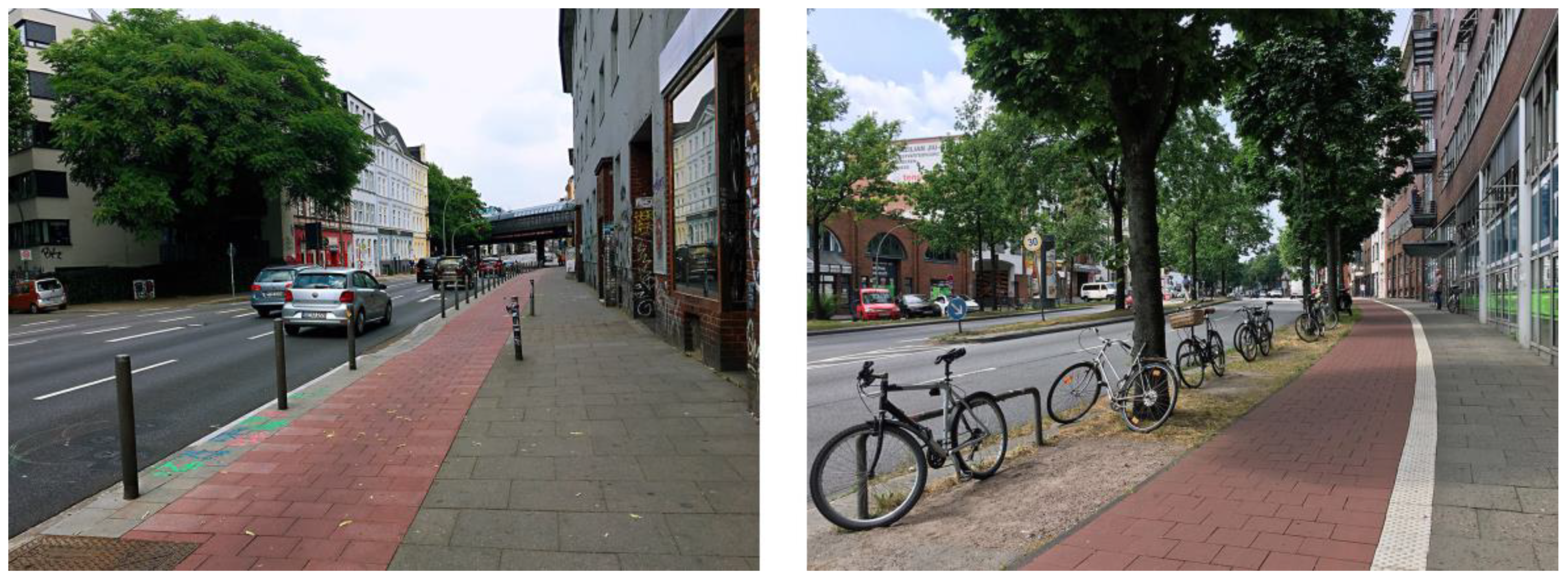

4.2.1. Physical Barriers

“So all the area as it is now—the split up between pedestrian, parking cars and bicycle—[are] from 1970s and 1980s, that means the time when Hamburg has the main goal to be a car-friendly city. […] They [the cycling lanes] are very very small, about 80 cm to 1 m. Of course there are very much conflicts with pedestrians.”[H2 Cycling planner]

“There are lots of cars parking there and also there are illegal parking. […] To modernize this road, many of this illegal parking had to gone. People are buying more and more cars, statistics shows they don’t drive these cars they buy, and of course they want to put them in front of their house.”[H2 Cycling planner]

4.2.2. Political and Institutional Barriers

“To be fair to the politicians, in general cycling is a good thing, and as soon as you get conflict of interests with motorized traffic or even with the public transport, then cycling does tend to fall aside quite quickly. […] As an example, when there was debate about having citywide 30 km/h rules with the exception in certain places and some of the main roads, they said that Hamburg economy will come to a standstill. […] So cycling has been moved up to the agenda but I would not say it’s a priority in Hamburg, definitely not.”[H1 Researcher]

“The port and the logistic lobby is very strong in Hamburg. And partly because of the problem of non-existence ring road, I mean we have Ring 1 and Ring 2, […] but we don’t have a sort of ring road in terms of a motorway where you could bypass Hamburg. If you go from east to west, you have to go through the city. […]. And then of course a lot of the port traffic, the lorries also have to travel across the city. […] This is an additional, in some cases an obstacle from the point of view of cycling.”[H1 Researcher]

“They [the citizens] want to participate more in the administration. […] They want to influence the road. […] Whether the tree in front of their house they want to keep, or whether there are parking spaces which they believed to be their own parking space in front of their house, and so on, so this is very complex.”[H2 Cycling planner]

“You shouldn’t start too small. […] The [parking facilities around] Saarlandstrasse [Station] is already full after a few days or weeks, if you have good conditions, people’s use may be exploding. I think sometimes Hamburg is also very careful, too careful, with the number. […] And I think they also underestimated that people are willing to ride a very long distance with their bikes; that is also important.”[H5 B + R planner]

“We have strategy for cycling but we have no official strategy yet for any of the other modes. It’s a little bit difficult you have sort of things moving one way on the one side and the other moves the other way on the other side, and there is no strategic overlap and overview of where you want to go.”[H1 Researcher]

4.2.3. Social and Cultural Barriers

“They [Shop owners] are afraid if we take the car parking space away and put places for bike, they think they would get bankrupt, nobody would buy anything from them.”[H2 Cycling planner]

“And some cyclists are also motorists and they say ‘no, I wouldn’t want to give up my parking space’.”[H4 NGO]

4.2.4. Resource Barriers

“I don’t think money is the problem, but we don’t have enough engineers to do the planning work. […] We need more engineers. Road building companies don’t have as much engineers as we need to rebuild all the roads we want. So it takes some time.”[H2 Cycling planner]

4.2.5. Legal Barriers

4.3. Individual Level Barriers to Cycling

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.2. Suggestions for Overcoming Barriers

5.2.1. Cycling-Oriented Urban Design

5.2.2. Strategic and Integrated Planning for Cycling

5.2.3. Strong Political Support

5.2.4. Communication

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category of Barriers | Subcategory of Barriers | Example of Coding Passages |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | Lack of space | “This city is finished, that means we have no free spaces available to use for bike transport, we have to take some of the area which is now used for something else.” [H2] “We don’t have place, we always have houses next to the roads and we have a lot of trees next to the roads.” [H4] “In Dammtor [Station] it is really difficult because there is no space anywhere, there are so many bikes because the university is close to it, and it is so important to improve the facilities.” [H5] |

| Political and institutional | Lack of political support | “The economic cars the trucks. […] The politicians always say ‘we can’t stop it, it’s important for Hamburg.’ […] Many points [when] there are not enough space, always the cars are the winners, but not the bikes.” [H4] “At the moment, the competition is not fair, because the privilege of car is not accessible to the bike.” [H2] |

| Lack of evaluation of travel behavior and demand | “Actually, if everything that is written in there is actually implemented, it would be great. But the problem is they haven’t assigned definite resources on a year-by-year basis. […] If you say you are going towards some kind of goal but you didn’t measure where you are, obviously it’s difficult to say whether you have actually made some progress.” [H1] | |

| Time-consuming negotiation with private stakeholders on road space redistribution | “Every road is special so you have to discuss every road, it is a hard process and it takes a long time to think how we can do it here. Sometimes there is also a problem, the first part of the road we have one solution for bikes and it changed for the next part, […] and that for both cars and bicycles is difficult.” [H4] | |

| Lack of long-term and integrated planning | “We always say you have to think about the plan; you have to think about the cycling for the next ten years, or 15 years.” [H4] | |

| Landscape conflicts between cycling infrastructure and local landscape | “Some stations are very old, there are monument conservation. […] Because many people would like to leave their bikes under roofs to keep it dry, and especially these roofs at the main station, the city planning authority does not want any roofs around there, […] they want to protect the view of the old buildings.” [H5] | |

| Social and cultural | People’s reluctance to give up on-street car parking space | “There are also some people who are very critical to this new idea of ride a bike. […] Some people are afraid that someone would take their privilege of using cars away. […] So they try to stop it and they don’t like bikes to win the city and to get more space on the roads” [H2] |

| People’s reluctance to use on-road cycling lanes | “The people in Hamburg are used to use this very small bicycle ways next to the pedestrian. […] The cyclists are afraid to ride near the car traffic. So they don’t like this new bike lane. […] This is a challenge as well to convince these people who are afraid of using the modern infrastructure.” [H2] | |

| Resource | Lack of engineers | “[…] they can’t realize the concept for all the stations at the same time because there are too less people” [H5] |

| Legal | Not permitted to build new bridges for cyclists | “We want to improve the quality [of cycling infrastructure] and we don’t want to drive [ride] with trucks on the same road. […] So we need to increase the bridge or to add a new part for pedestrian and the bike traffic, it’s always said no, it’s not possible because our rule is no new bridges for no one and at no circumstances.” [H2] |

References

- Handy, S.; van Wee, B.; Kroesen, M. Promoting cycling for transport: Research needs and challenges. Transp. Rev. 2014, 34, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucher, J.; Dill, J.; Handy, S. Infrastructure, programs, and policies to increase bicycling: An international review. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 2010, 50, S106–S125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, X. Bike-sharing systems and congestion: Evidence from US cities. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 65, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Deng, W.; Song, Y. Ridership and effectiveness of bikesharing: The effects of urban features and system characteristics on daily use and turnover rate of public bikes in China. Transp. Policy 2014, 35, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götschi, T.; Garrard, J.; Giles-Corti, B. Cycling as a part of daily life: A review of health perspectives. Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hartog, J.J.; Boogaard, H.; Nijland, H.; Hoek, G. Do the health benefits of cycling outweigh the risks? Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, L.E.; Gärling, T.; Ettema, D.; Friman, M.; Fujii, S. Happiness and satisfaction with work commute. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 111, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raser, E.; Gaupp-Berghausen, M.; Dons, E.; Anaya-Boig, E.; Avila-Palencia, I.; Brand, C.; Castro, A.; Clark, A.; Eriksson, U.; Götschi, T.; et al. European cyclists’ travel behavior: Differences and similarities between seven European (PASTA) cities. J. Transp. Health 2018, 9, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauder, S.A.; Foley, M.C. The relationship between active transportation and health. J. Transp. Health 2015, 2, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, A.; Evans, J.; Schliwa, G. Policy learning and sustainable urban transitions: Mobilising Berlin’s cycling renaissance. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 2739–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Carstensen, T.A.; Nielsen, T.A.S.; Olafsson, A.S. Bicycle-friendly infrastructure planning in Beijing and Copenhagen—Between adapting design solutions and learning local planning cultures. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 68, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzendorf, M.; Busch-Geertsema, A. The cycling boom in large German cities-Empirical evidence for successful cycling campaigns. Transp. Policy 2014, 36, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucher, J.; Buehler, R. Making cycling irresistible: Lessons from the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. Transp. Rev. 2008, 28, 495–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, R.; Pucher, J.; Gerike, R.; Götschi, T. Reducing car dependence in the heart of Europe: Lessons from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, R. Determinants of transport mode choice: A comparison of Germany and the USA. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucher, J.; Buehler, R. At the frontiers of cycling: Policy innovations in the Netherlands, Denmark, and Germany. World Transp. Policy Pract. 2007, 13, 8–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Police perspectives on road safety and transport politics in Germany. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Statistical Office (Destatis). Commuter. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/EN/FactsFigures/NationalEconomyEnvironment/LabourMarket/Employment/TablesCommuter/Commuter1.html (accessed on 22 January 2018).

- Deffner, J.; Hefter, T.; Rudolph, C.; Ziel, T. Handbook on Cycling Inclusive Planning and Promotion: Capacity Development Material for the Multiplier Training within the mobile2020 Project. Available online: http://www.mobile2020.eu/get-trained/handbook.html (accessed on 24 October 2017).

- Fernández-Heredia, Á.; Monzón, A.; Jara-Díaz, S. Understanding cyclists’ perceptions, keys for a successful bicycle promotion. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2014, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaugh, K.; Boisjoly, G.; El-Geneidy, A. Overcoming barriers to cycling: Understanding frequency of cycling in a University setting and the factors preventing commuters from cycling on a regular basis. Transportation (Amst) 2017, 44, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, R.L. Perceived traffic risk for cyclists: The impact of near miss and collision experiences. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 75, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titze, S.; Stronegger, W.J.; Janschitz, S.; Oja, P. Association of built-environment, social-environment and personal factors with bicycling as a mode of transportation among Austrian city dwellers. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 2008, 47, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sousa, A.A.; Sanches, S.P.; Ferreira, M.A.G. Perception of barriers for the use of bicycles. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 160, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, M.; Rissel, C. Perspectives and images of cycling as a barrier or facilitator of cycling. Transp. Policy 2011, 18, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldred, R.; Jungnickel, K. Why culture matters for transport policy: The case of cycling in the UK. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 34, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein. Monatszahlen—Bevölkerung—Statistikamt Nord. Available online: https://www.statistik-nord.de/zahlen-fakten/bevoelkerung/monatszahlen/?inputTree%5B%5D=c%3A2&prevInputTree%5B%5D=c%3A2&inputTree%5B%5D=t%3A1&prevInputTree%5B%5D=t%3A1&filter%5Blocation%5D=2&showAllYears=&filter%5BadditionalTopics%5D= (accessed on 19 November 2017).

- Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg. Mobilitätsprogramm 2013 Grundlage für eine kontinuierliche Verkehrsentwicklungsplanung in Hamburg. Available online: http://www.hamburg.de/contentblob/4119700/50fd34e0e06432b8ea113bf40cfc6ca7/data/mobilitaetsprogramm-2013.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2018).

- ADFC Hamburg. Fahrradklimatest 2016. Available online: https://hamburg.adfc.de/verkehr/themen-a-z/fahrradklimatest-2016/ (accessed on 17 June 2018).

- Forsyth, A.; Krizek, K.J. Promoting walking and bicycling: Assessing the evidence to assist planners. Built Environ. 2010, 36, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, C.E.; Wendel-Vos, G.C.W.; den Broeder, J.M.; van Kempen, E.E.M.M.; van Wesemael, P.J.V.; Schuit, A.J. Shifting from car to active transport: A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2014, 70, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, R.; Dill, J. Bikeway networks: A review of effects on cycling. Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, L.; Bertolini, L.; Brömmelstroet, M.T. Performance of municipal cycling policies in medium-Sized cities in the Netherlands since 2000. Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 134–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savan, B.; Cohlmeyer, E.; Ledsham, T. Integrated strategies to accelerate the adoption of cycling for transportation. Transp. Res. Part F Psychol. Behav. 2017, 46, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, P.; Daniel, V. Determinants of bicycle use: Do municipal policies matter? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2004, 38, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Urban transport transitions: Copenhagen, city of cyclists. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 33, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Garvill, J.; Nordlund, A.M. Acceptability of single and combined transport policy measures: The importance of environmental and policy specific beliefs. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2008, 42, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, A.D.; Kelly, C.; Shepherd, S. The principles of integration in urban transport strategies. Transp. Policy 2006, 13, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigar, G. Local “barriers” to environmentally sustainable transport planning. Local Environ. 2000, 5, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, K.; Antonson, H.; Eriksson, L. Layering and parallel policy making—Complementary concepts for understanding implementation challenges related to sustainable mobility. Transp. Policy 2017, 53, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banister, D. Overcoming barriers to the implementation of sustainable transport. In Barriers to Sustainable Transport. Institutions, Regulation and Sustainability; Rietveld, P., Stough, R., Eds.; Spon Press: London, UK, 2005; pp. 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Aldred, R.; Watson, T.; Lovelace, R.; Woodcock, J. Barriers to investing in cycling: Stakeholder views from England. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koglin, T.; Rye, T. The marginalisation of bicycling in modernist urban transport planning. J. Transp. Health 2014, 1, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. Cycling on the verge: The discursive marginalisation of cycling in contemporary New Zealand transport policy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 18, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffron, P. The implementation of walking and cycling policies in British local authorities. Transp. Policy 2003, 10, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marije de Boer, M.A.H.; Caprotti, F. Getting Londoners on two wheels: A comparative approach analysing London’s potential pathways to a cycling transition. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 32, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerike, R.; Jones, P. Strategic planning of bicycle networks as part of an integrated approach. In Cycling Futures: From Research into Practice; Gerike, R., Parkin, J., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016; pp. 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Nordtømme, M.E.; Bjerkan, K.Y.; Sund, A.B. Barriers to urban freight policy implementation: The case of urban consolidation center in Oslo. Transp. Policy 2015, 44, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M. Policy analytical capacity and evidence-based policy-making: Lessons from Canada. Can. Public Adm. 2009, 52, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazkiewicz, A.; Challies, E.; Newig, J. Public participation and local environmental planning: Testing factors influencing decision quality and implementation in four case studies from Germany. Land Use Policy 2015, 46, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg. Alliance for Cycling. Available online: http://www.hamburg.de/contentblob/7182614/5dfef803916523ef5784e59b7c5c4107/data/buendnis-fuer-den-radverkehr-download-english.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2017).

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bergin, M. NVivo 8 and consistency in data analysis: Reflecting on the use of a qualitative data analysis program. Nurse Res. 2011, 18, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg. Cycling Action Plan for Hamburg. Available online: https://www.hamburg.de/contentblob/129682/9d37bbb142c189e8a3ddad3d4566d896/data/radverkehrsstrategie-fuer-hamburg.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2017).

- Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg. Radverkehrsstrategie für Hamburg Fortschrittsbericht 2015. Available online: http://www.hamburg.de/contentblob/4538022/f80b2806d74a33dba4f404dd319d10ce/data/fortschrittsbericht-2015.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2017).

- Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg. Hamburg—European Green Capital: 5 Years On. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/europeangreencapital/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Hamburg-EGC-5-Years-On_web.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2017).

- Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg. B+R-Entwicklungskonzept für die Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg. Available online: http://www.hamburg.de/contentblob/5356254/005b068a33ee53b4b9ff87b20ce7c2e5/data/b-und-r-entwicklungskonzept.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2017).

- Koglin, T. Vélomobility and the politics of transport planning. GeoJournal 2015, 80, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follmer, R. Mobilität in Deutschland 2017: Kurzreport. Verkehrsaufkommen—Struktur—Trends. Available online: http://www.mobilitaet-in-deutschland.de/pdf/infas_Mobilitaet_in_Deutschland_2017_Kurzreport.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- Gössling, S.; Schröder, M.; Späth, P.; Freytag, T. Urban space distribution and sustainable transport. Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 659–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; Swartling, Å.G.; Jäger, J. Participation of experts and non-experts in a sustainability assessment of mobility. Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A.; Krizek, K. Urban design: Is there a distinctive view from the bicycle? J. Urban Des. 2011, 16, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathcart-Keays, A. Oslo’s Car Ban Sounded Simple Enough. Then the Backlash Began | Cities | The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/jun/13/oslo-ban-cars-backlash-parking (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- Dufour, D. Cycling Ploicy Guide: Cycling Infrastructure. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/intelligent/projects/sites/iee-projects/files/projects/documents/presto_policy_guide_cycling_infrastructure_en.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- Heydon, R.; Martin, L.-S. Making Space for Cycling—A Guide for New Developments and Street Renewals. Available online: www.makingspaceforcycling.org (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- DiGioia, J.; Watkins, K.E.; Xu, Y.; Rodgers, M.; Guensler, R. Safety impacts of bicycle infrastructure: A critical review. J. Saf. Res. 2017, 61, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, C. Planning for sustainable accessibility: The implementation challenge. Transp. Policy 2008, 15, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffner, J.; Hefter, T. Sustainable mobility cultures and the role of cycling planning professionals. ISOE Policy Br. 2015, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bagloee, S.A.; Sarvi, M.; Wallace, M. Bicycle lane priority: Promoting bicycle as a green mode even in congested urban area. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 87, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanillos, G.; Zaltz Austwick, M.; Ettema, D.; De Kruijf, J. Big Data and Cycling. Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanczyk, R. PRESTO Cycling Policy Guide: Promotion of Cycling. Available online: ec.europa.eu/energy/intelligent/projects/sites/iee-projects/files/projects/documents/presto_policy_guide_promotion_of_cycling_en.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2017).

| Category of Barrier 1 | Description 1 | Cycling—Related Example |

|---|---|---|

| Resource | Problems in acquiring an adequate amount of financial and physical resources in time | Not enough investments [42] |

| Institutional and political | Problems in the cooperation between organizations and conflicts among different policies | Lack of leadership and political will [42] |

| Social and cultural | Problems in public acceptability of the measures | The public’s resistance to construct or use certain types of cycling infrastructure |

| Legal | Measures can be restricted or even cancelled by laws and regulations | Cycling lane construction is not permitted on certain roads |

| Side effects | The effects on other activities | Increased traffic risks for cyclists |

| Other (physical) | Space or topography restriction | Lack of space for cycling lanes, unsuitable topography [41] |

| Reference Code | Position | Organization |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Senior transport engineer and researcher | Hamburg University of Technology (Technische Universität Hamburg) |

| H2 | Cycling planner | Ministry of Economy, Transport and Innovation (Behörde für Wirtschaft, Verkehr und Innovation) |

| H3 | Senior transport planner | Ministry of Economy, Transport and Innovation (Behörde für Wirtschaft, Verkehr und Innovation) |

| H4 | Staff and transport policy consultant | The German Cyclist’s Association (Allgemeine Deutsche Fahrrad-Club e. V.) (ADFC) |

| H5 | Staff for B + R (bike-and-ride) | The Hamburg Public Transport Association (Hamburger Verkehrsverbund GmbH) (HVV) |

| Type | Document | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Action plan | Cycling Action Plan for Hamburg | 2007 | [54] |

| Action plan | Alliance for Cycling | 2016 | [51] |

| Progress report | Cycling strategy for Hamburg: Progress report 2015 | 2015 | [55] |

| Progress report | Hamburg—European Green Capital: 5 Years On. | 2016 | [56] |

| Development concept | B + R development concept for the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg | 2015 | [57] |

| Mobility program | Mobility program 2013—Basis for continuous transport development planning in Hamburg. | 2013 | [28] |

| Planner’s presentation | Cycling in Hamburg | 2017 | from a local planner |

| Category of Barriers | Number of Times Mentioned |

|---|---|

| Physical | |

| Lack of space | 12 |

| Political and institutional | |

| Lack of political support | 10 |

| Lack of evaluation of travel behavior and demand | 6 |

| Time-consuming negotiation with private stakeholders on road space redistribution | 4 |

| Lack of long-term and integrated planning | 3 |

| Landscape conflicts between cycling infrastructure and local landscape | 3 |

| Social and cultural | |

| People’s reluctance to give up on-street car parking space | 4 |

| People’s reluctance to use on-road cycling lanes | 3 |

| Resource | |

| Lack of engineers | 3 |

| Legal | |

| Not permitted to build new bridges for cyclists | 1 |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L. Barriers to Implementing Pro-Cycling Policies: A Case Study of Hamburg. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114196

Wang L. Barriers to Implementing Pro-Cycling Policies: A Case Study of Hamburg. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):4196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114196

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Luqi. 2018. "Barriers to Implementing Pro-Cycling Policies: A Case Study of Hamburg" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 4196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114196

APA StyleWang, L. (2018). Barriers to Implementing Pro-Cycling Policies: A Case Study of Hamburg. Sustainability, 10(11), 4196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114196