Leisure Motivation and Satisfaction: A Text Mining of Yoga Centres, Yoga Consumers, and Their Interactions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Yoga Styles

1.2. Yoga Guidance

2. Literature Review

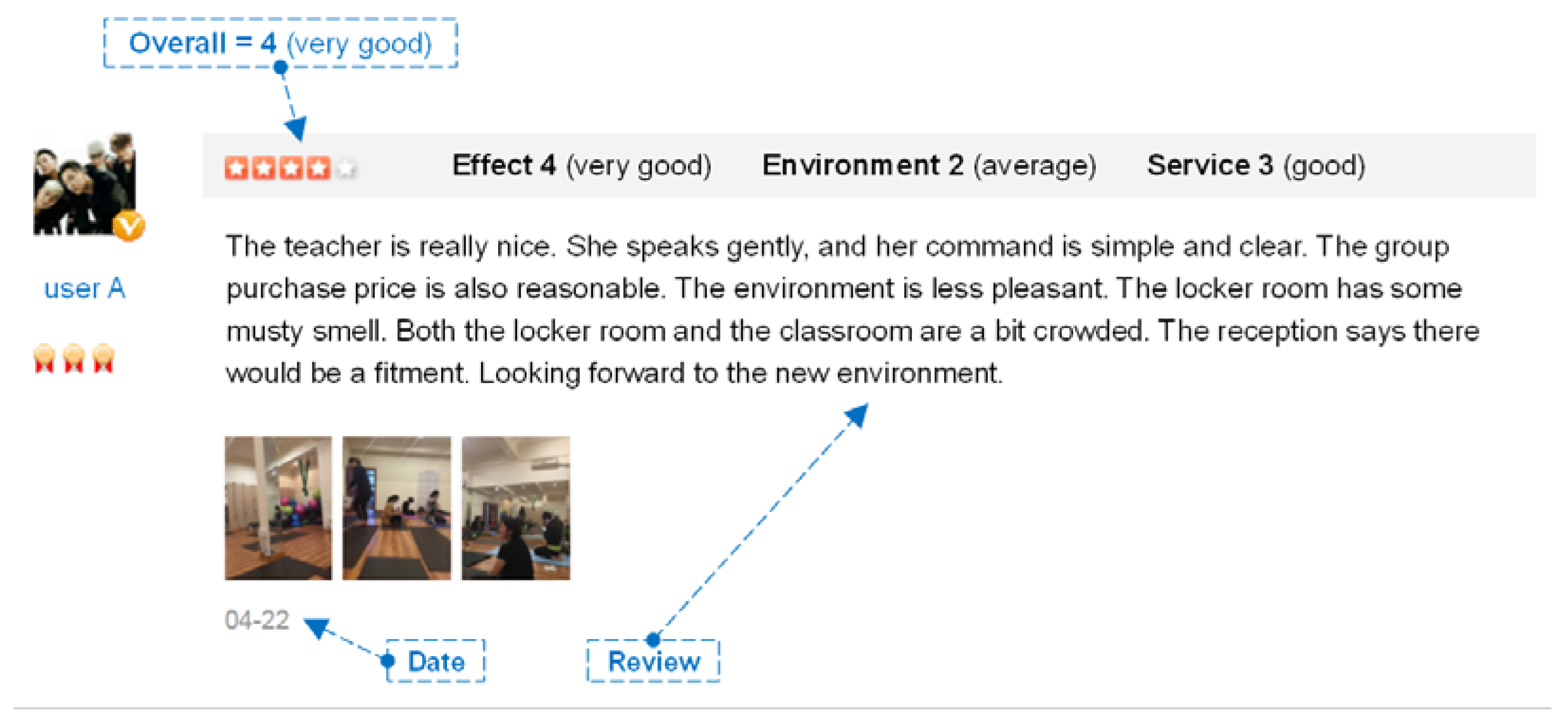

2.1. UGC Analysis

2.2. Yogi Motivation

2.3. Yoga Service and Yogi Satisfaction

3. Methods

3.1. Research Questions

3.2. Data Sampling

3.3. Topic Identification Using LDA

- (1)

- Randomly choose a distribution of topics;

- (2)

- For each word in the document,

- (a)

- Randomly choose a topic from the distribution of topics in (1);

- (b)

- Randomly choose a word from the corresponding distribution of the vocabulary.

- The coach helps me greatly.

- Our teacher is extremely patient.

- The price is reasonable.

- The membership card is expensive, but I though it worth the price.

- The coach is nice, and the price is OK.

- Sentence (1) and (2): 100% Topic A.

- Sentence (3) and (4): 100% Topic B.

- Sentence (5): 50% Topic A, 50% Topic B.

- Topic A: 30% coach, 20%, teacher, 10% nice, 5% patient, … (at which point one would interpret Topic A to be about coach).

- Topic B: 40% price, 30% membership, 15% worth, 5% expensive, … (at which point one would interpret Topic B to be about membership price).

- βi

- Distribution of word in topic i, altogether K topics;

- θd

- Proportions of topics in document d, altogether D documents;

- zd

- Topic assignment in document d;

- zd,n

- Topic assignment for the nth word in document d, altogether N words;

- wd

- Observed words for document d;

- wd,n

- The nth word for document d.

3.4. Word Frequency Analysis

3.5. Topic Frequency Analysis

- ti,d

- Number of times a word in document d is allocated to topic i;

- Σi ti,d

- Number of words in document d.

4. Results

4.1. Rating Distribution

4.2. Topics Identified Using LDA

4.3. Yoga Style Word Frequency

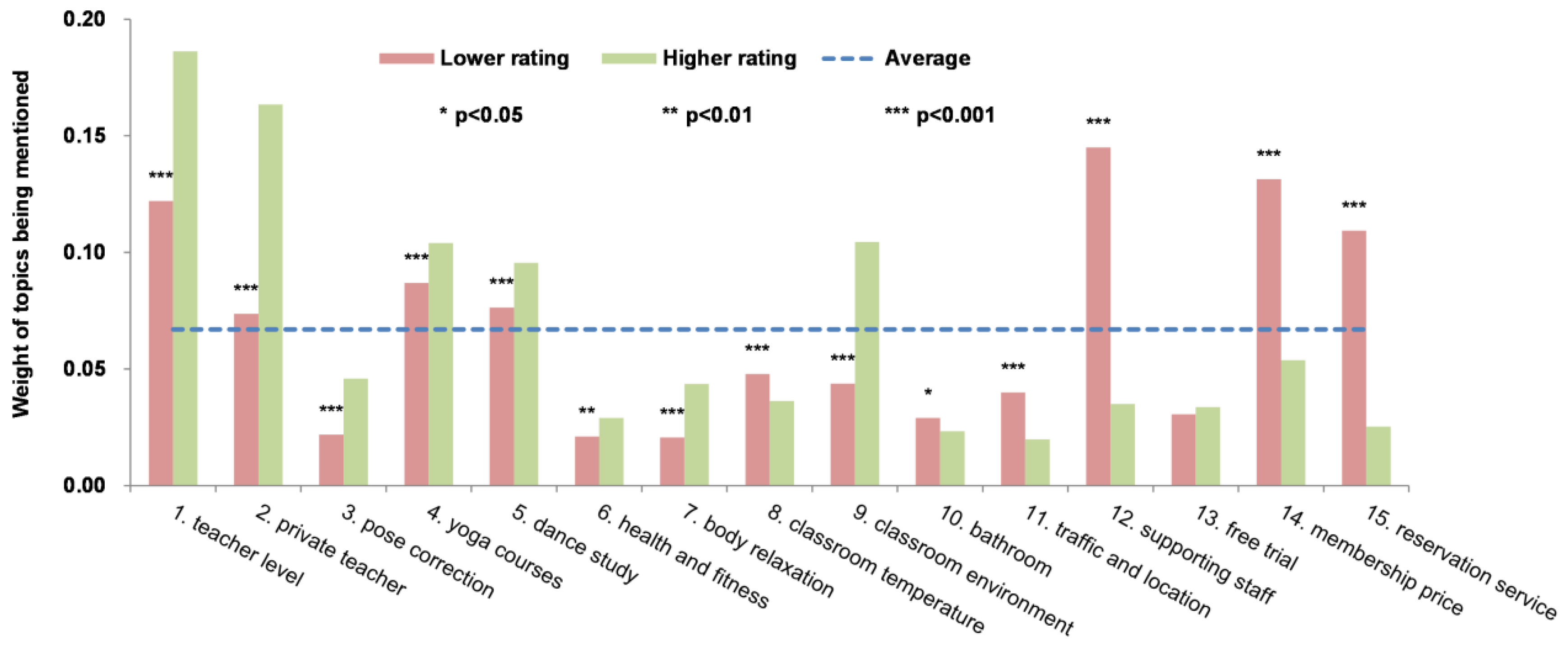

4.4. Weight of Topics Being Mentioned

5. Discussion

5.1. Yogi Motivation

“I was in a small class where I had a good relationship with the teacher and the classmates. The classroom was finely decorated, warm, and sweet. The teacher would design different poses for us and arrange formations. Real fun. We had a special class member, Ms. Cat, who came to visit us time and again. Every one enjoyed the course and we are still connected on SNS.”(user ID: shadow_and_sand)

“Yoga is associated with quietness and comfort. After a full day of fast-tempo work during which I had to communicate with numerous people, it was nice to calm myself down and enjoy the tranquillity. I was stretching every part of my body, drenched in sweat. The coda of the course was perfect, with music slowed and light dimmed. Fully relaxed.”(user ID: judy_zhangqi)

5.2. Yoga Service Execution

5.3. Yoga Consumer Satisfaction

5.4. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Managerial Contributions

6.2. Limitations and Future Study Suggestions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sherman, K.J.; Cherkin, D.C.; Erro, J.; Miglioretti, D.L.; Deyo, R.A. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 143, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, E.; Collette-Merrill, K. Effectiveness of integrative restoration (iRest) yoga nidra on mindfulness, sleep, and pain in health care workers. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2018, 32, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manocha, R.; Marks, G.B.; Kenchington, P.; Peters, D.; Salome, C.M. Sahaia yoga in the management of moderate to severe asthma: A randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2002, 57, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culos-Reed, S.N.; Carlson, L.E.; Daroux, L.M.; Hately-Aldous, S. A pilot study of yoga for breast cancer survivors: Physical and psychological benefits. Psycho-Oncol. 2006, 15, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood, G.; Rampes, H.; Tuffrey, V.; Richardson, J.; Pilkington, K. Yoga for anxiety: A systematic review of the research evidence. Br. J. Sport Med. 2005, 39, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenes, G.A.; Divers, J.; Miller, M.E.; Danhauer, S.C. A randomized preference trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and yoga for the treatment of worry in anxious older adults. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2018, 10, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolery, A.; Myers, H.; Sternlieb, B.; Zeltzer, L. A yoga intervention for young adults with elevated symptoms of depression. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2004, 10, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pilkington, K.; Kirkwood, G.; Rampes, H.; Richardson, J. Yoga for depression: The research evidence. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 89, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chung, Y.N.; Park, I.-H. The service quality and the customer satisfaction of yoga center. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2005, 44, 463–474. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, J. The effect of service quality on customers intention to revisit, and word of mouth intention in yoga center. Korea Sport Res. 2006, 17, 439–448. [Google Scholar]

- Il, L.S.; Yu, H. The influence of yoga center’s service quality to customer satisfaction and repurchase intention. J. Sport Leisure Stud. 2007, 31, 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-Y. The effects of service quality, image, service value on customer’s satisfaction and customer’s intention to revisit: Focus on yoga center service quality. J. Prod. Res. 2007, 25, 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Jing, Y.; Cai, E.; Cui, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. How leisure venues are and why? A geospatial perspective in Wuhan, central China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Che, S.; Xie, C.; Tian, S. Understanding Shanghai residents’ perception of leisure impact and experience satisfaction of urban community parks: An integrated and IPA method. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños, R.; Ruiz-Juan, F.; Baena-Extremera, A.; García-Montes, M.E.; Ortiz-Camacho, M.M. Leisure-time physical activity in relation to the stages of changes and achievement goals in adolescents: Comparative study of students in Spain, Costa Rica, and Mexico. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.T.; Liu, X.R.; Li, J.J. Market segmentation by travel motivations under a transforming economy: Evidence from the Monte Carlo of the Orient. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijing: Scale of China’s Yoga Boom Revealed for First Time. Available online: https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/chinas-yoga-yoga-boom-in-china-china-yoga-industry-development-report-978243-2017-05-20 (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- Cramer, H.; Lauche, R.; Langhorst, J.; Dobos, G. Is one yoga style better than another? A systematic review of associations of yoga style and conclusions in randomized yoga trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2016, 25, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaChiusa, I.C. The transformation of ashtanga yoga: Implicit memory, dreams, and consciousness for survivors of complex trauma. Neuroquantology 2016, 14, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.A.; Petronis, J.; Smith, D.; Goodrich, D.; Wu, J.; Ravi, N.; Doyle, E.J.; Juckett, R.G.; Kolar, M.M.; Gross, R.; et al. Effect of Iyengar yoga therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain 2005, 115, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, B.L.; Hart, C.E.F. Bikram yoga training and physical fitness in healthy young adults. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, S.A.; Rogers, R.J.; Davis, K.K.; Minster, R.L.; Creasy, S.A.; Mullarkey, N.C.; O’Dell, M.; Donahue, P.; Jakicic, J.M. Energy expenditure in vinyasa yoga versus walking. J. Phys. Act. Health 2017, 14, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raub, J.A. Psychophysiologic effects of Hatha Yoga on musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary function: A literature review. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2002, 8, 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.M.; Tseng, W.S.; Ting, L.F.; Huang, G.F. Development and evaluation of a yoga exercise programme for older adults. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 57, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.; Chandra, S.; Dubey, A.K. Exploration of lower frequency EEG dynamics and cortical alpha asymmetry in long-term rajyoga meditators. Int. J. Yoga 2018, 11, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Penman, S.; Cohen, M.; Stevens, P.; Jackson, S. Yoga in Australia: Results of a national survey. Int. J. Yoga 2012, 5, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telles, S.; Sharma, S.K.; Singh, N.; Balkrishna, A. Characteristics of yoga practitioners, motivators, and yoga techniques of choice: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Michelis, E. A preliminary survey of modern yoga studies. Asian Med. 2007, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L.; Riley, K.E.; Besedin, E.Y.; Stewart, V.M. Discrepancies between perceptions of real and ideal yoga teachers and their relationship to emotional well-being. Int. J. Yoga Ther. 2013, 23, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, A.; Touchton-Leonard, K.; Yang, L.; Wallen, G. A national survey of yoga instructors and their delivery of yoga therapy. Int. J. Yoga Ther. 2016, 26, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lea, J.; Philo, C.; Cadman, L. “It’s a fine line between ... self discipline, devotion and dedication”: Negotiating authority in the teaching and learning of Ashtanga yoga. Cult. Geogr. 2016, 23, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavanani, A.B. A brief qualitative survey on the utilization of Yoga research resources by Yoga teachers. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 5, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greysen, H.M.; Greysen, S.R.; Lee, K.A.; Hong, O.S.; Katz, P.; Leutwyler, H. A qualitative study exploring community yoga practice in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2017, 23, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, I.; Getz, D.; Gubb, K. The social world and event travel career of the serious yoga devotee. Leisure Stud. 2016, 35, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, V.; Chang, E.A. Does chatter matter? The impact of user-generated content on music sales. J. Interact. Mark. 2009, 23, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Law, R.; Gu, B.; Chen, W. The influence of user-generated content on traveler behavior: An empirical investigation on the effects of e-word-of-mouth to hotel online bookings. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susarla, A.; Oh, J.H.; Tan, Y. Social networks and the diffusion of user-generated content: Evidence from YouTube. Inf. Syst. Res. 2012, 23, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransbotham, S.; Kane, G.C.; Lurie, N.H. Network characteristics and the value of collaborative user-generated content. Market. Sci. 2012, 31, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Magruder, J. Learning from the crowd: Regression discontinuity estimates of the effects of an online review database. Econ. J. 2012, 122, 957–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.Y.; Bradlow, E.T. Automated marketing research using online customer reviews. J. Market. Res. 2011, 48, 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büschken, J.; Allenby, G.M. Sentence-based text analysis for customer reviews. Market. Sci. 2016, 35, 953–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Zhang, K.; Wang, W.; Gao, G. A tale of two countries: International comparison of online doctor reviews between China and the United States. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2017, 99, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.; Banerjee, T.; Muppalla, R.; Romine, W.; Sheth, A. What are people tweeting about Zika? An exploratory study concerning symptoms, treatment, transmission, and prevention. JMIR Public Health Surveil. 2017, 3, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blei, D.M. Probabilistic topic models. Commun. ACM 2012, 55, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosh, D.; Guha, R. What are we ‘tweeting’ about obesity? Mapping tweets with topic modeling and geographic information system. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 40, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Burns, A.C.; Hou, Y. An investigation of brand-related user-generated content on Twitter. J. Advertis. 2017, 46, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Menendez, A.; Saura, J.R.; Alvarez-Alonso, C. Understanding #WorldEnvironmentDay user opinions in Twitter: A topic-based sentiment analysis approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2537. [Google Scholar]

- Närvänen, E.; Saarijärvi, H.; Simanainen, O. Understanding consumers’ online conversation practices in the context of convenience food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R. Netnography: Doing Ethnographic Research Online; Sage: London, UK, 2010; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Zhai, Y. Social structure and evolvement of WeChat groups: A case study based on text mining. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inf. 2016, 35, 617–629. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, R. Multi-brand loyalty: When one brand is not enough. Qual. Mark. Res. 2014, 17, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Jiang, Z.G. Extracting topic-sensitive content from textual documents: A hybrid topic model approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2018, 70, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L. Analyzing consumer online group buying motivations: An interpretive structural modeling approach. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, S.; Bar-Eli, M.; Morris, T.; Moore, M. Measuring motivation for physical activity: An exploratory study of PALMS, The Physical Activity and Leisure Motivation Scale. Athlet. Insight 2012, 4, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Brems, C.; Justice, L.; Sulenes, K.; Girasa, L.; Ray, J.; Davis, M.; Freitas, J.; Shean, M.; Colgan, D. Improving access to yoga: Barriers to and motivators for practice among health professions students. Adv. Mind-Body Med. 2015, 29, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Watts, A.W.; Rydell, S.A.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Laska, M.N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Yoga’s potential for promoting healthy eating and physical activity behaviors among young adults: A mixed-methods study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahlo, L.; Tiggemann, M. Yoga and positive body image: A test of the Embodiment Model. Body Image 2016, 18, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocanu, E.; Mohr, C.; Pouyan, N.; Thuillard, S.; Dan-Glauser, E.S. Reasons, years and frequency of yoga practice: Effect on emotion response reactivity. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergeer, I. Participation motives for a holistic dance-movement practice. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 16, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellem, T.; Ferguson, H. An Internet-based survey of the dance fitness program OULA. Sage Open Med. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.L.; Riley, K.E.; Bedesin, E.; Stewart, V.M. Why practice yoga? Practitioners’ motivations for adopting and maintaining yoga practice. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz-Heik, R.J.; Meyer, H.; Mahoney, L.; Stanton, M.V.; Cho, R.H.; Moore-Downing, D.P.; Avery, T.J.; Lazzeroni, L.C.; Varni, J.M.; Collery, L.M.; et al. Results from a clinical yoga program for veterans: Yoga via telehealth provides comparable satisfaction and health improvements to in-person yoga. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; MacLehose, R.F.; Watts, A.W.; Pacanowski, C.R.; Eisenberg, M.E. Yoga and body image: Findings from a large population-based study of young adults. Body Image 2018, 24, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejati, S.; Rajezi Esfahani, S.; Rahmani, S.; Afrookhteh, G.; Hoveida, S. The effect of group mindfulness-based stress reduction and consciousness yoga program on quality of life and fatigue severity in patients with MS. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 5, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepburn, S.J.; McMahon, M. Pranayama meditation (yoga breathing) for stress relief: Is it beneficial for teachers? Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 42, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzano, A.N.; Anderson, C.E.; Hylton, C.; Gustat, J. Effect of mindfulness and yoga on quality of life for elementary school students and teachers: Results of a randomized controlled school-based study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2018, 11, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingues, R.B. Modern postural yoga as a mental health promoting tool: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Clin. 2018, 31, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyez, A.C. The ‘world of yoga’: The production and reproduction of therapeutic landscapes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.L.; Wang, N.; Sun, Y.Q.; Xiang, L. Unleash the power of mobile word-of-mouth: An empirical study of system and information characteristics in ubiquitous decision making. Online Inf. Rev. 2013, 37, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhen, F.; Zhu, S.; Xi, G. Spatial pattern of catering industry in Nanjing urban area based on the degree of public praise from internet: A case study of Dianping.com. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2014, 34, 810–817. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg, L. The hard work of working out: Defining leisure, health, and beauty in a Japanese fitness club. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2000, 24, 260–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasson, J.; Johansson, T. The new fitness geography: The globalisation of Japanese gym and fitness culture. Leisure Stud. 2015, 36, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öner, Ö.; Klaesson, J. Location of leisure: The new economic geography of leisure services. Leisure Stud. 2017, 36, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, T.L.; Steyvers, M. Finding scientific topics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 5228–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- LDA 1.0.5: Topic Modeling with Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Available online: https://pypi.python.org/pypi/lda/ (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- Bodet, G. Loyalty in sport participation services: An examination of the mediating role of psychological commitment. J. Sport Manag. 2012, 26, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahwiler, P.; Havitz, M.E. Toward a relational understanding of leisure social worlds, involvement, psychological commitment, and behavioral loyalty. Leisure Sci. 1998, 20, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis, N.D.; Kaplanidou, K.K.; Karabaxoglou, I. Effect of event service quality and satisfaction on happiness among runners of a recurring sport event. Leisure Sci. 2015, 37, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, T.W.; Lindestad, B. Customer loyalty and complex services: The impact of corporate image on quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty for customers with varying degrees of service expertise. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1998, 9, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, C.K.; Tse, D.K.; Chan, K.W. Strengthening customer loyalty through intimacy and passion: Roles of customer-firm affection and customer-staff relationships in services. J. Market. Res. 2008, 45, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kandampully, J.; Zhang, T.T.; Bilgihan, A. Customer loyalty: A review and future directions with a special focus on the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 379–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | References | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ye et al. [36] | Anderson et al. [39] | Lee et al. [40] | Büschken et al. [41] | Hao et al. [42] | Miller et al. [43] | Gosh et al. [45] | Liu et al. [46] | This Research | |

| Online rating | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Online review | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| LDA | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Topic frequency | - | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Purposes | References | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [50] | Felix [51] | Liang et al. [52] | Xiao et al. [53] | Büschken et al. [41] | Hao et al. [42] | This Research | |

| Motivation | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - | √ |

| Satisfaction | - | - | - | - | √ | √ | √ |

| Topic Name * | Words in the Topic (Numbers in the Brackets Indicate Frequency of Word) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. teacher level | teacher (24,232) | professional (5189) | teach (2582) | service (2310) | nice (1028) |

| kind (1004) | patient (887) | gentle (794) | super (783) | lady (668) | |

| 2. private teacher | teacher (24,232) | patience (3170) | small class (2003) | private (1374) | effect (1723) |

| course (955) | situation (734) | one-to-one (480) | excellent (465) | aim (256) | |

| 3. pose correction | pose (5356) | correction (2214) | instruction (1647) | in place (1008) | posture (825) |

| explain (675) | position (641) | careful (576) | adjust (564) | standard (273) | |

| 4. yoga courses | suit (1239) | aerial (827) | night (725) | rookie (703) | Bikram (645) |

| therapy (612) | Pilates (556) | difficulty (550) | noon (357) | hatha (209) | |

| 5. dance study | class (5640) | foundation (1722) | dance (1364) | belly dance (824) | experience (707) |

| study (705) | learn (586) | jump (530) | dancing (344) | jazz (277) | |

| 6. health and fitness | month (1313) | body shape (748) | persist (697) | lose weight (580) | strive (498) |

| cheer (459) | expect (446) | healthy (422) | effort (311) | slim (289) | |

| 7. body relaxation | body (2956) | comfort (2489) | relax (1668) | stretch (649) | work (605) |

| neck and shoulder (573) | breathe (569) | mood (348) | enjoy (339) | pressure (200) | |

| 8. classroom temperature | classroom (3852) | place (3492) | warm (578) | mat (410) | winter (366) |

| cushion (349) | hot (325) | space (287) | floor heating (272) | air conditioning (230) | |

| 9. classroom environment | environment (10,118) | classroom (3852) | cosy (1747) | decoration (963) | comfortable (833) |

| intimate (714) | quiet (672) | tidy (468) | layout (436) | elegant (432) | |

| 10. bathroom | bathroom (1536) | clean (1990) | facility (850) | bath (741) | towel (564) |

| locker room (331) | change clothes (326) | shower (284) | slippers (256) | water (225) | |

| 11. traffic and location | traffic (1074) | area (647) | find (625) | subway (585) | road (570) |

| location (560) | beside (401) | convenient (211) | parking (208) | park (202) | |

| 12. supporting staff | zeal (1533) | front desk (1548) | attitude (1071) | boss (894) | promotion (821) |

| introduce (786) | staff (785) | sales (764) | reception (635) | consultant (561) | |

| 13. free trial | free (1390) | prize (1164) | activity (1126) | thank (915) | dine and dash (900) |

| twice (679) | opportunity (662) | happy (636) | participate (601) | lucky (487) | |

| 14. membership price | card (3241) | open (2219) | membership (1723) | price (1576) | year (1240) |

| expensive (476) | RMB (476) | annual card (404) | cheap (350) | transfer (238) | |

| 15. reservation service | time (2445) | reservation (2419) | phone (815) | ahead (708) | remind (476) |

| WeChat (426) | actively (405) | timetable (277) | late (275) | confirm (184) | |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, S. Leisure Motivation and Satisfaction: A Text Mining of Yoga Centres, Yoga Consumers, and Their Interactions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124458

Jia S. Leisure Motivation and Satisfaction: A Text Mining of Yoga Centres, Yoga Consumers, and Their Interactions. Sustainability. 2018; 10(12):4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124458

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Susan (Sixue). 2018. "Leisure Motivation and Satisfaction: A Text Mining of Yoga Centres, Yoga Consumers, and Their Interactions" Sustainability 10, no. 12: 4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124458

APA StyleJia, S. (2018). Leisure Motivation and Satisfaction: A Text Mining of Yoga Centres, Yoga Consumers, and Their Interactions. Sustainability, 10(12), 4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124458