Determinants of Innovation Cooperation Performance: What Do We Know and What Should We Know?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

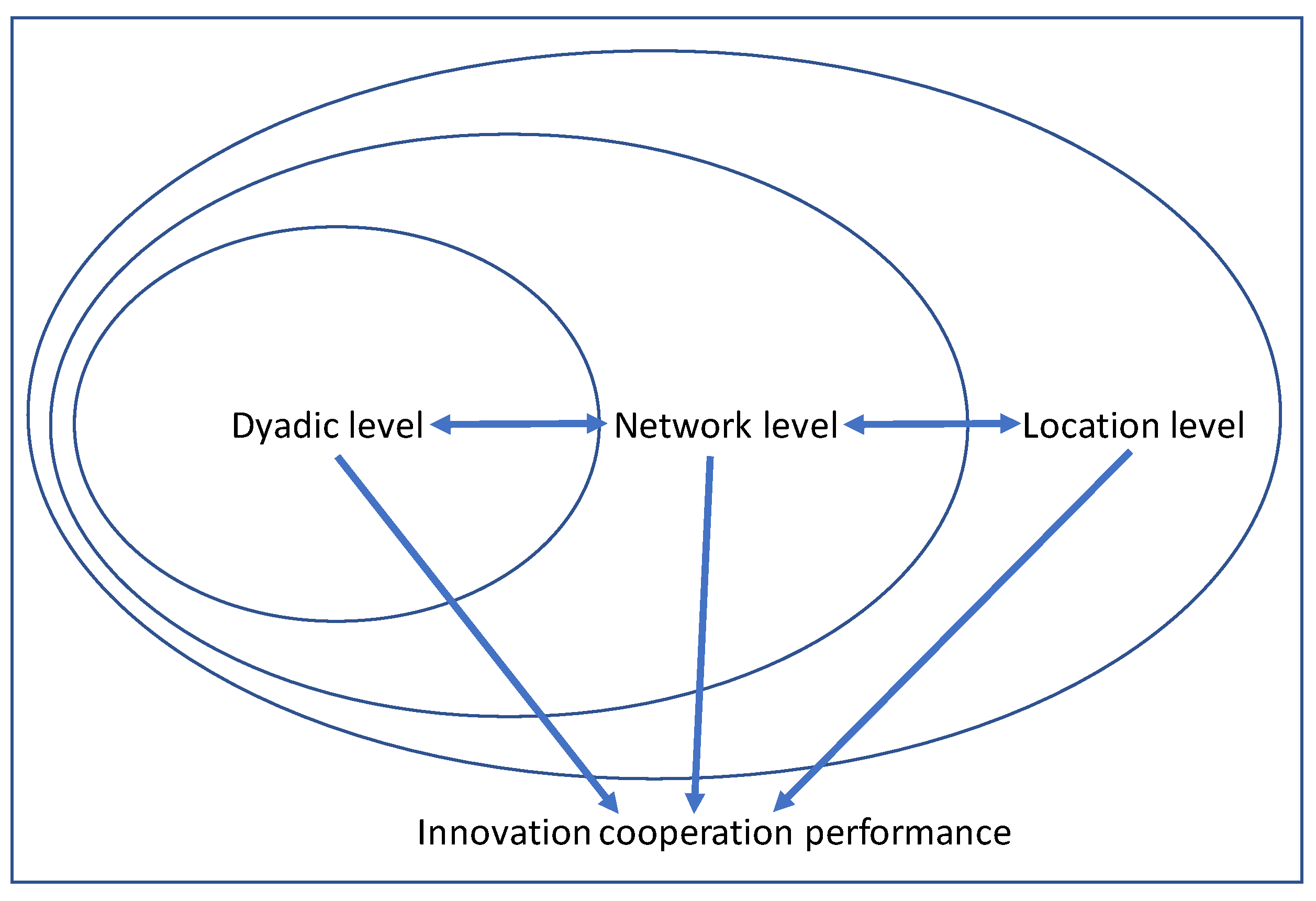

2. Conceptual Framework and Review Methodology

- Geographical proximity, which is a spatial dimension to the physical distance between actors;

- organizational proximity, this is when companies share the same relationships and technology;

- social proximity, related to interactions based on trust and knowledge between stakeholders;

- institutional proximity, based on the set of practices, laws, rules and routines that facilitate collective action; and

- cognitive proximity, which occurs when companies share the same references and knowledge.

3. Literature Review Results

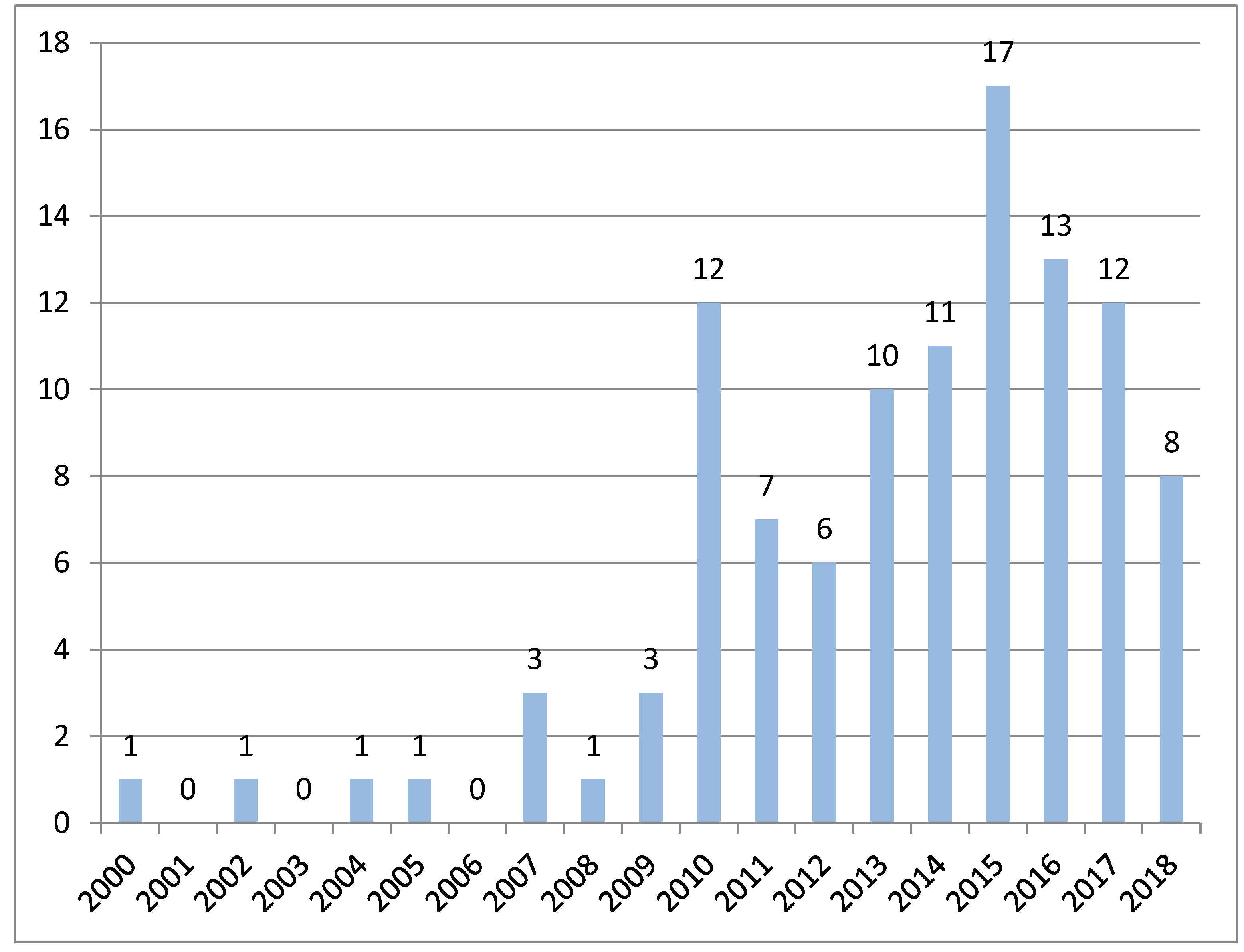

3.1. Review Methodology

- For the location level: STP, science and technology park, clusters, proximity, geographical proximity, innovation performance, innovation, cooperation, and firm performance.

- For the network level: innovation networks, alliance portfolios, inter-firm cooperation, innovation performance, and firm performance.

- For the dyadic level: Open Innovation, Open Innovation Alliances, Innovation Cooperation, Innovation Performance, R&D Alliances, Strategic Technology Alliances, Business-Academia Alliances, Biopharma, Biopharmaceutical industry, and firm performance.

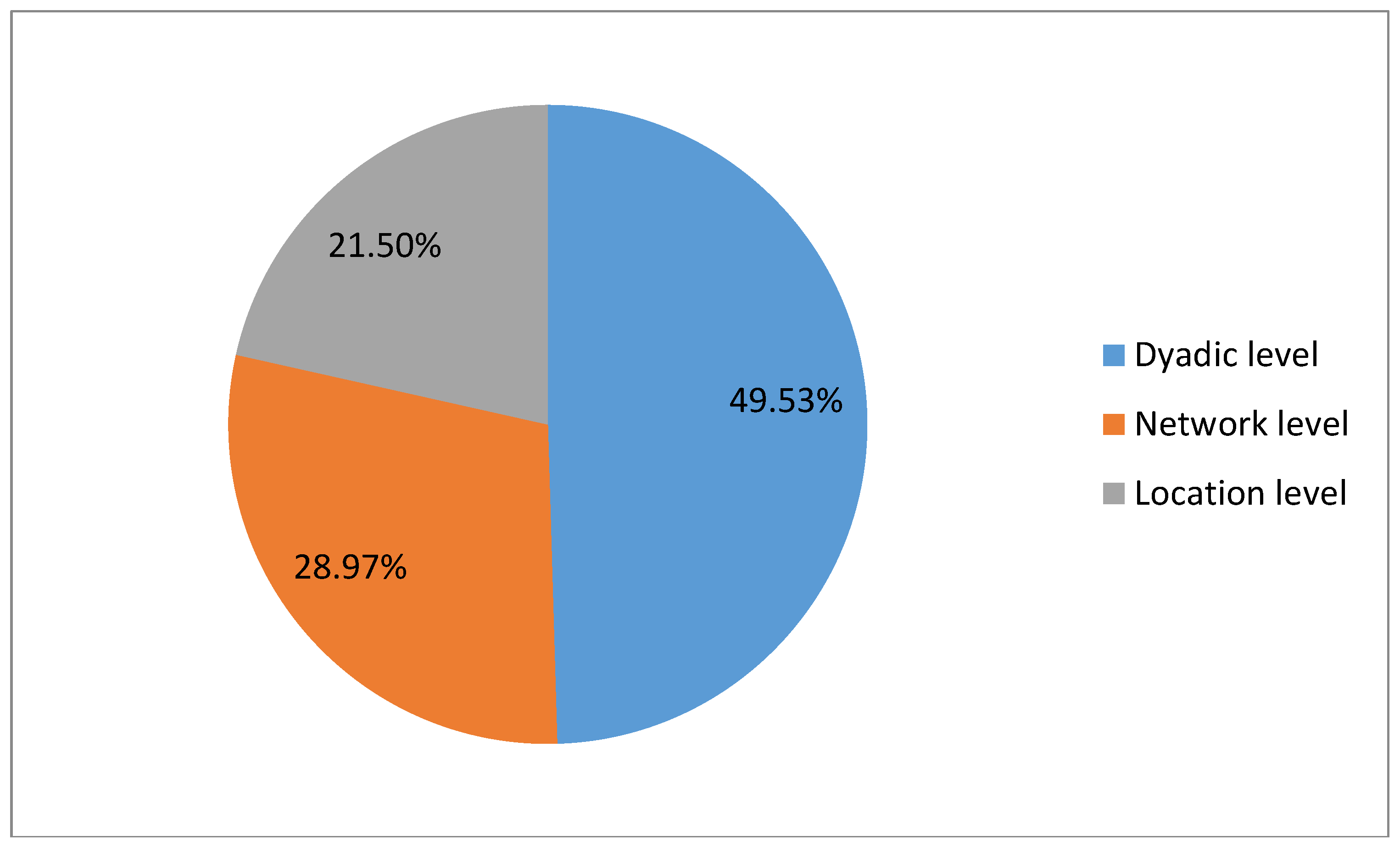

3.2. Overall Findings

- Location level

- Network level

- Dyadic level

3.3. Findings at the Dyadic Level

3.3.1. Open Innovation and Determinants of Cooperation Form

3.3.2. Characteristics of Partners, Innovation Cooperation Determinants and Performance

3.4. Findings at the Network Level

3.4.1. Alliance Portfolios

3.4.2. Network Design

3.5. Findings at the Location Level

3.5.1. Clusters and STPs

3.5.2. Importance of Proximity and Networks

3.5.3. Institutional Environment

4. Directions for Future Research and Practical Implications

4.1. Dyadic Level

4.2. Network Level

4.3. Location Level

4.4. Interactions between Levels

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Overview of Specific Research Areas and Research Focus

| Level of Analysis | Research Area | Research Focus | # of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dyadic level | Characteristics of partners in inter-firm cooperation | Alliance partner resources | 4 |

| Learning and innovation cooperation performance | 1 | ||

| Partner diversity and alliances performance | 1 | ||

| Prior alliance experience | 1 | ||

| Determinants of cooperation form | Alliance network technological diversity | 1 | |

| Alliances vs. acquisitions | 1 | ||

| Determinants of alliance type | 2 | ||

| Determinants of cooperation form | 1 | ||

| Governance form determinants | 1 | ||

| Innovation performance | 1 | ||

| OIA and value co-creation | 1 | ||

| Potential absorptive capacity | 1 | ||

| Technological complexity and alliance complexity | 1 | ||

| Innovation cooperation determinants and performance | Alliance characteristics and performance | 1 | |

| Alliance performance determinants | 1 | ||

| Business-university cooperation | 1 | ||

| Determinants of alliance performance | 2 | ||

| Exploration and exploitation | 1 | ||

| Innovation cooperation | 1 | ||

| Prior experience and performance | 1 | ||

| Vertical-downstream and vertical-upstream alliances | 1 | ||

| Open innovation | Business-university cooperation | 2 | |

| Determinants of cooperation form | 2 | ||

| Inbound open innovation and firm performance | 1 | ||

| Innovation and financial performance | 1 | ||

| Innovation cooperation | 7 | ||

| Innovation networks | 1 | ||

| Innovation performance | 5 | ||

| Knowledge transfer | 2 | ||

| Measuring Open Innovation | 2 | ||

| Network management and innovation performance | 1 | ||

| Open innovation modes | 1 | ||

| Organisational modes | 1 | ||

| Potential absorptive capacity | 1 | ||

| Network level | Alliance portfolios | Portfolio diversity and performance | 16 |

| Coopetition | 2 | ||

| Portfolio internationalization | 1 | ||

| Alliance networks and performance | 3 | ||

| Antecedents of multilateral alliances | 1 | ||

| Alliance portfolio R&D intensity | 3 | ||

| Partner types | 1 | ||

| Network design | Relative position in network | 4 | |

| Location level | Clusters and STPs | Business-university cooperation | 4 |

| Innovation performance | 3 | ||

| Open innovation | 1 | ||

| Importance of proximity and networks | Business-university cooperation | 2 | |

| Cooperation effects | 4 | ||

| Knowledge transfer | 2 | ||

| Regional networks | 3 | ||

| Institutional environment | Access and transfer of knowledge | 1 | |

| Cooperation effects | 3 |

References

- Piga, C.A.; Vivarelli, M. Internal and external R&D: A sample selection approach. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2004, 66, 457–482. [Google Scholar]

- Trigo, A.; Vence, X. Scope and patterns of innovation cooperation in Spanish service enterprises. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veugelers, R.; Cassiman, B. Make and buy in innovation strategies: Evidence from Belgian manufacturing firms. Res. Policy 1999, 28, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassiman, B.; Veugelers, R. R&D cooperation and spillovers: Some empirical evidence from Belgium. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.W. The Era of Open Innovation. Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 44, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Jaklič, A.; Damijan, J.P.; Rojec, M.; Kunčič, A. Relevance of innovation cooperation for firms’ innovation activity: The case of Slovenia. Econ. Res. Èkon. Istraž. 2014, 27, 645–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contractor, F.J.; Lorange, P. The growth of alliances in the knowledge-based economy. Int. Bus. Rev. 2002, 11, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, M.; Lukas, R. Who cooperates on R&D? Res. Policy 2001, 30, 297–312. [Google Scholar]

- George, G.; Zahra, S.A.; Wheatley, K.K.; Khan, R. The effects of alliance portfolio characteristics and absorptive capacity on performance: A study of biotechnology firms. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2001, 12, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, D.; Miller, S.R. Alliance portfolio internationalization and firm performance. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strat. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W.; Bogers, M. Explicating open innovation: Clarifying an emerging paradigm for understanding innovation. In New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Chesbrough, H.W., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- West, J.; Salter, A.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; Chesbrough, H. Open innovation: The next decade. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanko, M.A.; Fisher, G.J.; Bogers, M. Under the wide umbrella of open innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2017, 34, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batkovskiy, A.M.; Kalachikhin, P.A.; Semenova, E.G.; Telnov, Y.F.; Fomina, A.V.; Balashov, V.M. Configuration of enterprise networks. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2018, 6, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B.B. Determining international strategic alliance performance: A multidimensional approach. Int. Bus. Rev. 2007, 16, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, R.B. Innovation by operating practices in project alliances–when size matters. Br. J. Manag. 2011, 22, 586–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Oh, W.; Im, K.S.; Chang, R.M.; Oh, H.; Pinsonneault, A. Value cocreation and wealth spillover in open innovation alliances. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.C. R&D alliances and firm performance: The impact of technological diversity and alliance organization on innovation. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 364–386. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaverbeke, W.; Duysters, G.; Noorderhaven, N. External technology sourcing through alliances or acquisitions: An analysis of the application-specific integrated circuits industry. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 714–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatotchev, I.; Piga, C.; Dyomina, N. Network positioning and R&D activity: A study of Italian groups. R D Manag. 2003, 33, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.J.; Srivastava, M.K.; Gnyawali, D.R. Impact of coopetition in the alliance portfolio and coopetition experience on firm innovation. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2014, 26, 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassmer, U. Alliance portfolios: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.S.; O’Connor, G. Alliance portfolio resource diversity and firm innovation. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Černevičiūtė, J. Cultural and Creative Industries (CCI) and sustainable development: China’s cultural industries clusters. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2017, 5, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toselli, M. Knowledge sources and integration ties toward innovation. A food sector perspective. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2017, 7, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, S. Multilevel heterogeneity of R&D cooperation and innovation determinants. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2017, 7, 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Prause, G.; Atari, S. On sustainable production networks for Industry 4.0. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2017, 4, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, C. Technology Policy and Economic Performance: Lessons from Japan; Pinter: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Fomina, A.V.; Berduygina, O.N.; Shatsky, A.A. Industrial cooperation and its influence on sustainable economic growth. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2018, 5, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monni, S.; Palumbo, F.; Tvaronavičienė, M. Cluster performance: An attempt to evaluate the Lithuanian case. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2017, 5, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsouri, M. Knowledge Networks in Emerging ICT Regional Innovation Systems: An Explorative Study of the Knowledge Network of Trentino ICT Innovation System. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Trento, Trento, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boschma, R.; Frenken, K. The spatial evolution of innovation networks: A proximity perspective. In The Handbook of Evolutionary Economic Geography; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boschma, R. Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoben, J.; Oerlemans, L.A. Proximity and inter-organizational collaboration: A literature review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2006, 8, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Capaldo, A.; Messeni Petruzzelli, A. Origins of knowledge and innovation in R&D alliances: A contingency approach. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2015, 27, 461–483. [Google Scholar]

- Fitjar, R.D.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Networking, context and firm-level innovation: Cooperation through the regional filter in Norway. Geoforum 2015, 63, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, T.; Sagsan, M. The Concept of ‘Knowledgization’ for Creating Strategic Vision in Higher Education: A Case Study of Northern Cyprus. Educ. Sci. 2016, 41, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkut, B. Entrepreneurship and Economic Freedom—Do Objective and Subjective Data Reflect the Same Tendencies? Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2016, 4, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkut, B. Structural Similarities of Economies for Innovation and Competitiveness—A Decision Tree Based Approach. Stud. Oecon. Posnaniensia 2016, 4, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žižka, M.; Valentová, V.H.; Pelloneová, N.; Štichhauerová, E. The effect of clusters on the innovation performance of enterprises: Traditional vs. new industries. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2018, 5, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, S.; Kotulla, T. Standardization and Adaptation in International Marketing and Management—From a Critical Literature Analysis to a Theoretical Framework. In Strategies and Management of Internationalization and Foreign Operations; Larimo, J., Ed.; Vaasan Yliopiston Julkaisuja: Vaasa, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, C.M.; Martínez-López, F.J.; Coelho, F. The Determinants of Export Performance: A Review of the Research in the Literature between 1998 and 2005. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 10, 343–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Aryan, R.; Singh, S.; Kaur, T. A Systematic Review of literature about leadership and organization. Res. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Schuh, A.; Rossmann, A. Schwerpunkte und Trends in der betriebswirtschaftlichen Mittel-und Osteuropaforschung: Ein Literaturüberblick zum Zeitraum 1990–2005. In Internationale Unternehmensführung; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; pp. 161–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, M.; Cavaliere, A.; Chiaroni, D.; Frattini, F.; Chiesa, V. Organisational modes for Open Innovation in the bio-pharmaceutical industry: An exploratory analysis. Technovation 2011, 31, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelino, F.; Lamberti, E.; Cammarano, A.; Caputo, M. Open innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: An empirical analysis on context features, internal R&D, and financial performances. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2015, 62, 421–435. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.J.; Jeong, E.; Park, J. Network analysis of open innovation. Sustainability 2016, 8, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangus, K.; Drnovšek, M.; Di Minin, A.; Spithoven, A. The role of open innovation and absorptive capacity in innovation performance: Empirical evidence from Slovenia. J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2017, 22, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zynga, A.; Diener, K.; Ihl, C.; Lüttgens, D.; Piller, F.; Scherb, B. Making Open Innovation Stick: A Study of Open Innovation Implementation in 756 Global Organizations. Res. Technol. Manag. 2018, 61, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.; Kim, S.J.; Park, G. How does the partner type in R&D alliances impact technological innovation performance? A study on the Korean biotechnology industry. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2016, 33, 141–164. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Li, H.; Wu, X. Network resources and the innovation performance: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1207–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shu, C.; Jiang, X.; Malter, A.J. Managing knowledge for innovation: The role of cooperation, competition, and alliance nationality. J. Int. Mark. 2010, 18, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucena, A.; Roper, S. Absorptive capacity and ambidexterity in R&D: Linking technology alliance diversity and firm innovation. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2016, 13, 159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, H.; Rothaermel, F.T. The effect of general and partner-specific alliance experience on joint R&D project performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 332–345. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R.C. Experience effects and collaborative returns in R&D alliances. Strat. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 1009–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaisavljevic, V.; Cabello-Medina, C.; Pérez-Luño, A. Coping with diversity in alliances for innovation: The role of relational social capital and knowledge codifiability. Br. J. Manag. 2016, 27, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, C.; Zand, F. R&D cooperation, partner diversity, and innovation performance: An empirical analysis. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 292–312. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald, K.D.S.; Pennings, H.P.G.; Van Den Bosch, J.F.; Commandeur, H.R.; Claassen, E. The moderating role of absorptive capacity and the differential effects of acquisitions and alliances on Big Pharma firms’ innovation performance. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 0172488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pustovrh, A.; Jaklič, M.; Martin, S.A.; Rašković, M. Antecedents and determinants of high-tech SMEs’ commercialisation enablers: Opening the black box of open innovation practices. Econ. Res. Èkon. Istraž. 2017, 30, 1033–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbade, P.J.; Omta, S.W.O.; Fortuin, F.T. Exploring the characteristics of innovation alliances of Dutch Biotechnology SMEs and their policy implications. Bio-Based Appl. Econ. 2013, 2, 91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, R. Alliances and networks. Strat. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouaghi, F.; Garcia, M.; Garcia, M.S. Capturing value from Alliance Portfolio Diversity: The moderating role of R&D human capital. In Proceedings of the ISPIM Conference Proceedings (p. 1). The International Society for Professional Innovation Management (ISPIM), Budapest, Hungary, 14–17 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marhold, K.; Kim, M.J.; Kang, J. The effects of alliance portfolio diversity on innovation performance: A study of partner and alliance characteristics in the bio-pharmaceutical industry. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 1750001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, C.C. A longitudinal study of the influence of alliance network structure and composition on firm exploratory innovation. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 890–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.; Riley, J. Alliance Portfolio Diversity and Firm Performance: Examining Moderators. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 19, 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Oerlemans, L.A.; Knoben, J.; Pretorius, M.W. Alliance portfolio diversity, radical and incremental innoation: The moderating role of technology management. Technovation 2013, 33, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.G.; Zouaghi, F.; Garcia, M.S. Capturing value from alliance portfolio diversity: The mediating role of R&D human capital in high and low tech industries. Technovation 2017, 59, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Caner, T.; Tyler, B.B. Alliance portfolio R&D intensity and new product introduction. Am. J. Bus. 2013, 28, 38–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Wu, Y.J.; Chang, C.; Wang, W.; Lee, C.Y. The alliance innovation performance of R&D alliances—The absorptive capacity perspective. Technovation 2012, 32, 282–292. [Google Scholar]

- Piening, E.P.; Salge, T.O.; Schäfer, S. Innovating across boundaries: A portfolio perspective on innovation partnerships of multinational corporations. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Wang, M.C.; Huang, Y.C. The double-edged sword of technological diversity in R&D alliances: Network position and learning speed as moderators. Eur. Manag. J. 2015, 33, 450–461. [Google Scholar]

- Rogbeer, S.; Almahendra, R.; Ambos, B. Open-innovation effectiveness: When does the macro design of alliance portfolios matter? J. Int. Manag. 2014, 20, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golonka, M. Proactive cooperation with strangers: Enhancing complexity of the ICT firms’ alliance portfolio and their innovativeness. Eur. Manag. J. 2015, 33, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, T.; Lokshin, B.; Duysters, G. Returns to alliance portfolio diversity: The relative effects of partner diversity on firm’s innovative performance and productivity. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1839–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.M.; Soh, P.H. Linking alliance portfolios to recombinant innovation: The combined effects of diversity and alliance experience. Long Range Plan. 2017, 50, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.J.; Tao, Q.T.; Santoro, M.D. Alliance portfolio diversity and firm performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. Multilateral R&D alliances by new ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 241–260. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, T.E. Interorganizational alliances and the performance of firms: A study of growth and innovation rates in a high-technology industry. Strat. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 791–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Yang, H.; Arya, B. Alliance partners and firm performance: Resource complementarity and status association. Strat. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 921–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xiang, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, S. How to improve the performance of R&D alliance? An empirical analysis based on China’s pharmaceutical industry. Front. Bus. Res. China 2010, 4, 130–147. [Google Scholar]

- Filiou, D.; Golesorkhi, S. Influence of Institutional Differences on Firm Innovation from International Alliances. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, K.G.; Link, A.N.; Scott, J.T. Science and technology parks: An annotated and analytical literature review. J. Technol. Transf. 2017, 42, 957–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestle, V.; Täube, F.A.; Heidenreich, S.; Bogers, M. Establishing open innovation culture in cluster initiatives: The role of trust and information asymmetry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Urriago, Á.R.; Barge-Gil, A.; Rico, A.M. Science and technology parks and cooperation for innovation: Empirical evidence from Spain. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldes, C.; Heredia, J.; Felzensztein, C.; Mora, M. Proximity as determinant of business cooperation for technological and non-technological innovations: A study of an agribusiness cluster. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2017, 32, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniluk, A. Cooperation between Business Companies and the Institutions in the Context of Innovations Implementation. Procedia Eng. 2017, 182, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Vial, I.; Montoro-Sánchez, Á. How knowledge links with universities may foster innovation: The case of a science park. Technovation 2016, 50, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motohashi, K. The role of the science park in innovation performance of start-up firms: An empirical analysis of Tsinghua Science Park in Beijing. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2013, 19, 578–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovsky, L.; Simpson, H. Geographic proximity and firm–university innovation linkages: Evidence from Great Britain. J. Econ. Geogr. 2011, 11, 949–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt-Dundas, N. The role of proximity in university-business cooperation for innovation. J. Technol. Transf. 2013, 38, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.X.; Xie, X.M.; Tam, C.M. Relationship between cooperation networks and innovation performance of SMEs. Technovation 2010, 30, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P.N.; Boekholt, P.; Tödtling, F. The Governance of Innovation in Europe: Regional Perspectives on Global Competitiveness; Cengage Learning EMEA: Andover, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Doloreux, D. Regional networks of small and medium sized enterprises: Evidence from the metropolitan area of Ottawa in Canada. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2004, 12, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schøtt, T.; Jensen, K.W. Firms’ innovation benefiting from networking and institutional support: A global analysis of national and firm effects. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1233–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Martinez, M.; Lazzarotti, V.; Manzini, R.; Sánchez García, M. Open innovation strategies in the food and drink industry: Determinants and impact on innovation performance. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2014, 66, 212–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.G.; Doganova, L.; Piva, E.; D’Adda, D.; Mustar, P. Hybrid alliances and radical innovation: The performance implications of integrating exploration and exploitation. J. Technol. Transf. 2015, 40, 696–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Luo, X. Product alliances, alliance networks, and shareholder value: Evidence from the biopharmaceutical industry. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2015, 32, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangus, K.; Drnovšek, M. Open innovation in Slovenia: A comparative analysis of different firm sizes. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2013, 15, 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Rangus, K. Does a firm’s Open Innovation mode matter? Econ. Bus. Rev. 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleyn, D.; Kitney, R.; Atun, R.A. Partnership and innovation in the life sciences. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2007, 11, 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmacher, A.; Gassmann, O.; McCracken, N.; Hinder, M. Open innovation and external sources of innovation. An opportunity to fuel the R&D pipeline and enhance decision making? J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segers, J.P. Strategic Partnerships and Open Innovation in the Biotechnology Industry in Belgium. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2013, 3, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, J.P. The interplay between new technology based firms, strategic alliances and open innovation, within a regional systems of innovation context. The case of the biotechnology cluster in Belgium. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2015, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikhamn, B.R.; Wikhamn, W.; Styhre, A. Open innovation in SMEs: A study of the Swedish bio-pharmaceutical industry. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2016, 28, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybka, J.; Roijakkers, N.; Lundan, S.; Vanhaverbeke, W. Strategic Alliances for the Development of Innovative SMEs in the Biopharmaceutical Industry. Strategic Alliances for SME Development; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2015; pp. 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Radziwon, A.; Bogers, M. Open innovation in SMEs: Exploring inter-organizational relationships in an ecosystem. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Area | Specific Research Focus | Key Relationships Studied | Key Determinants of Innovation Cooperation Performance | Key Research Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of partners in interfirm cooperation | Alliance partner resources | Partner resources and innovation performance |

|

|

| Learning and innovation cooperation performance | Knowledge-innovation link and its moderators |

|

| |

| Partner diversity and alliances performance | Partner diversity-performance link and its moderators |

|

| |

| Prior alliance experience | Prior experience and performance |

|

| |

| Determinants of cooperation form | Determinants of alliance type | Technological innovation performance in different types of alliances (horizontal, vertical, hybrid, specialized, project alliances) |

|

|

| Innovation cooperation determinants and performance | Determinants of alliance performance | Impact of different alliance characteristics and different modes of innovation cooperation on the performance |

|

|

| Open Innovation | Open Innovation and firm performance | Impact of Open Innovation on innovation performance taking into consideration:

|

|

|

| Research Area | Specific Research Focus | Key Relationships Studied | Key Findings on the Determinants of Innovation Cooperation Performance | Key Research Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alliance portfolios | Portfolio diversity and performance | The effect of alliance portfolio diversity on firm innovation performance and the moderating effects thereon. |

|

|

| Determinants of alliance portfolio management | The impact of the macro-design of a firm’s alliance portfolio (international, technological, partner diversity) on its open-innovation effectivenessLinks among firms’ cooperation strategies, the complexity of their alliance portfolios, and their innovativeness. |

|

| |

| Coopetition | Coopetition in the portfolio and innovation performance. |

|

| |

| Portfolio internatio-nalization | Partner distance and performance |

|

| |

| Alliance networks and performance | Network position and performance |

|

| |

| antecedents of multilateral alliances | relationship between market uncertainty and likelihood of forming multilateral R&D alliances |

|

| |

| alliance portfolio R&D intensity | R&D intensity and new product introductions |

|

| |

| Partner types | Partner types and performance |

|

| |

| Network design | relative position in network | Network structure and knowledge benefits |

|

|

| Research Area | Specific Research Focus | Key Relationships Studied | Key Findings on the Determinants of Innovation Cooperation Performance | Key Research Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional environment | Access to knowledge | The relationship between innovation and external knowledge links. |

|

|

| Cooperation effects | Cooperation in the context of innovation creation between companies and other institutions. |

|

| |

| Importance of proximity and networks | Knowledge transfer | Knowledge flows. |

|

|

| Regional networks | The influence of regional networks on innovation performance. |

|

| |

| Business-university cooperation | Spatially mediated knowledge transfer from university research. |

|

| |

| Cooperation effects | Cooperation between companies and its effects. |

|

| |

| Clusters and STPs | Business-university cooperation | Cooperation between clusters or science parks and universities in terms of knowledge transfer. |

|

|

| Innovation performance | The impact of parks and clusters on innovative activity. |

|

| |

| Open Innovation | Open innovation processes between clustered firms |

|

|

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trąpczyński, P.; Puślecki, Ł.; Staszków, M. Determinants of Innovation Cooperation Performance: What Do We Know and What Should We Know? Sustainability 2018, 10, 4517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124517

Trąpczyński P, Puślecki Ł, Staszków M. Determinants of Innovation Cooperation Performance: What Do We Know and What Should We Know? Sustainability. 2018; 10(12):4517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124517

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrąpczyński, Piotr, Łukasz Puślecki, and Michał Staszków. 2018. "Determinants of Innovation Cooperation Performance: What Do We Know and What Should We Know?" Sustainability 10, no. 12: 4517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124517

APA StyleTrąpczyński, P., Puślecki, Ł., & Staszków, M. (2018). Determinants of Innovation Cooperation Performance: What Do We Know and What Should We Know? Sustainability, 10(12), 4517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124517