Abstract

The new and more conscious sensibility towards the environmental sphere supports the idea of “green city”, promotes initiatives of structural integration of the green with the built environment and involves a considerable number of disciplines in a cultural and social debate. The literature reports different experiences of collaborative governance, between administrations and citizens, which tend to enhance the interaction between the different social actors involved in the investments of Green Infrastructures, to share objectives and management methods and to assess the extent of ecosystem services. The objective of this article is to propose a methodological approach to assessing green investments in the urban area, which is able to internalize the social perception of citizens regarding this important component for the urban landscape, with a view to guiding the city’s government towards a new urban eco-social-green planning and evaluation model. It presents a concise framework of the scientific debate on climate change and on the effects of urban planning issues; some relevant experiences of Green Infrastructures; and the proposed methodology, applied to the reality of the “urban green system” of Catania, based on an integrated approach between participatory planning and the method NAIADE (Novel Approach to Imprecise Assessment and Decision Environments).

1. Introduction

There have been clear climatic variations on our planet for several decades, which since the last century have determined and will determine increasingly important negative impacts on the environment, on cities and on human health, such as to make climate change recognized as a global problem. Worldwide, the percentage of people living in urban areas will increase from 50.0% in 2010 to nearly 70.0% by 2150 [1]. For the first time in history, the population that lives in cities has surpassed the one that lives in the countryside or outside the inhabited centers, and this trend, which affects all countries of the world, has led to the creation of megalopolises, among the primary sources of pollution. In fact, most energy consumption is connected to cities, which have to make the greatest efforts to manage sustainable resources under the social, environmental and economic aspects and to improve the quality of life of their citizens. Heat waves in cities generate serious inconveniences for the most vulnerable citizens, especially the elderly and children. Therefore, cities must understand the significant role that they are called to play, not only in the implementation of the law and the provisions that are necessary at the various levels, but also in broader initiatives, to ensure the best quality of life in urban areas. Climate impact requires the use of innovative solutions and the rethinking of urban management and planning. New urban and territorial structures, low energy consumption buildings and infrastructures, green areas and the adoption of advanced technologies mitigate global emissions and local pollution, promote adaptation to climate change, reduce the energy costs of families and businesses and improve the climate of cities. In the development of the metropolitan city, the connotation of urban green space (or “urban green system”) has extended, to include the green space of the complex urban ecosystem, composed of various forms of non-built spaces, including gardens, parks, vertical plants, forestry, agricultural land, wetlands and waterways (green and blue infrastructures) [2,3,4,5,6].

The “green city” has always embodied an ideal of universal appeal that transcends temporal, spatial and cultural gaps [7]. The new and more conscious sensibility towards the environmental sphere, faced with the imbalances in contemporary cities, supports the idea of a “green city”, promotes initiatives of structural integration of the green with the built environment and involves a considerable number of disciplines in a cultural and social debate. However, the “urban green system” is still perceived as a pure aesthetic experience and is included in our urban plans almost exclusively with aesthetic-decorative functions. In this regard, the literature defines urban green as that portion of undeveloped territory, public or private property that coexists with structures and artifacts and is intended for enjoyment and health of the community [6,8,9]. Among the many indicators developed at various levels by national and international bodies, urban green is presented to pursue the objectives of urban sustainability, thanks to the acknowledged contribution to the quality of life in the city. Among the criteria used to assess the degree of livability of urban environments, the presence and extent of urban and periurban green spaces, multi-purpose areas for leisure and high-quality urban furniture appear [10,11,12]. Several studies show the existence of important links between urban green and impacts on climatic conditions (the removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, the more bearable urban conditions and the reduction of the heat island effect) [13,14,15,16,17]. Parks and trees offer shaded areas and help to cool the air, they are places to find relief during heat waves, they offer plant cover, and they protect from solar radiation. Green surfaces also absorb heat and have lower thermal inertia than concrete or asphalt surfaces, therefore, the integration of vegetation in the facades and on the roofs of buildings (Green Infrastructures (GI)) helps to balance the interior temperatures as well as protect the structures.

In this framework, it becomes interesting to investigate the dynamics related to the relationship between GI and climate comfort within cities, on the role of the “urban green system” as an essential component in the planning process, in the policies of mitigation and adaptation to climate change and in the investment plans of the city, on the possible assessment by the community of the ecosystem services connected to it.

The objective of this article is to propose a methodological approach to assess green investments in urban areas, which can internalize the social perception of citizens regarding this important component for the urban landscape. In the first part, we offer a brief overview of the ongoing scientific debate on climate change and its immediate impact on urban planning issues, presenting some experiences of sustainable planning (linked to GI), in Italy and abroad.

This is followed by the evaluation of green planning policies and adaptation measures (so far) in the city of Catania to acquire useful information in order to guide the city government towards planning and evaluating the urban eco-social-green model. The methodology proposed and applied to the reality of the ”urban green system” of Catania and to the planning of investments in GIs, is based on an integrated approach between participatory planning techniques (based on the establishment of Focus Groups with the various stakeholders) and the NAIADE method (Novel Approach to Imprecise Assessment and Decision Environments) [18] (for the Multi-Critical Social Assessment (SMCE)) for the “complex” information collected (quantitative and qualitative data).

The aim is to develop a methodological structure made up of appropriate tools aimed, first, to the acquisition and, after, to the evaluation of the information (qualitative and quantitative) on possible alternative scenarios with respect to the proposed problem. The opinions were collected through specific meetings with local stakeholders, interested in the problem in question, under different economic, social and environmental aspects (the dimensions of sustainable development, that originated the model designation eco-social-green).

The proposed approach, based on a form of collaborative governance, offers a series of ideas, suggestions and recommendations aimed at introducing innovative choices in urban planning tools, which can be useful for Public Administrations and industry technicians, in the promotion of GI, starting from the already available assets, be it public or private.

2. The New Role of City Government towards a Model Resilient to Climate Change

Climate changes tend to accentuate critical issues already present in urban settlements, where the thermal characteristics of urban materials (asphalt, bricks, glass, etc.) contribute to increasing heat, creating inconveniences in the urban environment compared to periurban and rural areas. In fact, the average temperature of the cities is +2–3 °C compared to periurban and rural areas, and can reach +5–6 °C in summer with the formation of “heat islands”. Moreover, extreme meteorological phenomena for continuous cementification (flooding, landslides, etc.) are becoming more frequent. Therefore, the theme of adaptation to climate change must be integrated into all territorial policies and actions [19].

The European Union (E.U.) has given a strong impetus to the fight against climate change and environmental protection, through a path (The most recent stages are: Green Paper “Adapting to climate change in Europe—which possibilities for EU intervention”(2007); White Paper “Adapting to climate change: towards a European framework for action” (2009); and Preparatory phase DG CLIMA and Climate-ADAPT (2009–2013)) that finds its legal and objective basis in art. 191 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the E.U. The European Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change (2013) has the objective of making Europe more resilient to climate change, promoting greater coordination and sharing of information between Member States and encouraging the integration of adaptation into all EU policies. In particular, in the European strategy, two types of interventions are foreseen: mitigation and adaptation.

“Mitigation” refers to all those measures aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Actions aimed, on the one hand, to reduce anthropogenic emissions and, on the other hand, to increase the absorption capacity of the natural environment of greenhouse gases. Examples of mitigation include: the most efficient use of fossil fuels for industrial processes, transport, or for the generation of electricity;the replacement of fossil fuels with renewable energy sources (solar and wind energy);increasing the insulation of buildings; and the expansion of forests and other absorption basins to remove large amounts of CO2 from the atmosphere.

“Adaptation” includes all the preventive measures put in place to mitigate the impacts linked to the climate changes in progress.The two types of interventions differ in: time scale and spatial scale.

- Time scale: Adaptation measures are effective immediately; mitigation measures are effective in the long term.

- Spatial scale: Adaptation is typically local, while mitigation has global effects.

Urban adaptation strategies will be based on detailed climate resilience studies, which assess the expected impacts in each specific context, their type and their size, thus providing indispensable elements for defining action priorities and optimizing available economic resources (Adaptation Plans) [10,15,16,20].

The impacts of climate change in urban settlements are very diverse: health and quality of life (in particular the vulnerable groups of the population); buildings, water infrastructure, energy and transport; cultural heritage (due to landslides, floods and heat waves); and energy production and supply. Therefore, to effectively address these impacts, coordination of a very broad institutional network (multilevel governance) is required.

It will therefore be fundamental, in defining urban adaptation strategies, to actively involve citizens and other interested stakeholders to favor “non-regret” interventions that can remedy existing problems and bring immediate benefits and socio-economic benefits to increase adaptive capacity and actions based on an ecosystemic or “green” approach.

In particular, in the European strategy, the priority measures that an administrator can take in planning adaptation to uncertainty are:

- -

- “Low-regret” or “no-regret” measures produce benefits even in the absence of climate change and with which the costs of adaptation are relatively low compared to the benefits of the action.

- -

- “Win–win (–win)” measures achieve the desired result in terms of reducing climate risks or exploiting potential opportunities as well as bring other social, environmental or economic benefits.

- -

- Reversible and flexible options allow future changes.

- -

- Adding “safety margins” to new investments ensure that these responses are resistant to a range of future climate impacts.

- -

- “Soft” adaptation strategies could include building adaptation capacity to ensure that an organization is better able to cope with a range of climate impacts (e.g., through more effective proactive planning).

- -

- Reduction of decision time horizons.

- -

- Delaying action, i.e., long-term active adaptation strategy.

- -

- Actions based on an ecosystem or “green” approach.

- -

- Infrastructural and technological or “gray” actions in urban settlements include interventions aimed at preventing the increase of hydraulic and geomorphological risks; increasing the infrastructural facilities for cycling and pedestrian mobility; and encouraging the experimentation of new settlement models able to cope with climate changes (e.g., eco-neighborhoods, climate-houses, and climate upgrading).

Effective adaptation requires physical-technical, socio-cultural, environmental, economic and political measures to create a flexible system that functions even when individual parts fail [21].

Among the actions envisaged in the context of adaptation interventions in urban contexts, those related to actions based on an ecosystem or “green” approach are often included in the adaptation plans of the cities.

In particular, the actions envisaged are aimed:

- -

- to promote and encourage the diffusion of green roofs and the increase of public and private green areas also for the purpose of calming the extreme summer heat phenomena.

- -

- to implement, also for demonstrative purposes and to raise awareness among citizens, experimental interventions of climatic adaptation of public spaces in particularly vulnerable areas, such as increase the green facilities, the permeability of the soils, the social spaces, and the hydraulic performances.

- -

- to increase the endowment of urban green, adopting the logic of green and blue infrastructures, and safeguarding biodiversity in urban areas.

- -

- to support the spread of urban gardens, intended, as well as for educational purposes, also as targeted forms of redevelopment of underused green areas and as a contribution to the food autonomy of urban settlements.

In this framework of urban interventions aimed at fighting climate change, the “urban green system” assumes ever greater importance and becomes a multifunctional resource for the city and its inhabitants [22,23,24].

Municipalities are called to respond to climate problems with new governance tools to distribute the risk of impacts, which aim to involve citizens to a greater extent in the project proposals for interventions and measures. Indeed, it is important for urban governance to assess the social perception of investments in GI and to estimate the benefits of related ecosystem services. The interactions between stakeholders involved in urban projects have proved useful in different experiences, but have not yet been widely applied to climate change adaptation actions in cities.

The literature on collaborative governance presents different models of interaction between actors, in relation to the objectives pursued by shared projects, both environmental and social: public vs. private adaptation [25,26]; cross-sector partnerships [27]; cooperative or “hybrid” environmental governance [28,29]; co-creation and co-production [30]; adaptive co-management [31]; and social contracts of risk [32].

Active collaboration with citizens in local adaptation planning and in decision about GI is promoted by research and policy, including the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 and the Paris Agreement (2015). However, few studies have assessed empirical interactions between municipalities and citizens in this respect [33,34,35,36].The principle of sustainable urban development involves the transformation of social relations towards democracy and promotes the participation of citizens in social policies, with the identification of economic, social and environmental conditions capable of fully promoting relations between the citizens of the various social groups. The deliberation and the formation of consensus, different from the aggregation of individual preferences, are an effective way to make citizens aware of the value of urban green, a resource of collective interest [37,38].

3. Green Infrastructures and Urban Green as Tools for Climate Adaptation of Cities and for the Enhancement of Ecosystem Services

European cities have long been facing the issue of climate change, trying to make the urban environment more resilient. From northern Europe to the Mediterranean area, climate adaptation plans and experimental projects have been adopted or are being drafted for the creation of sustainable eco-neighborhoods, restoration of the banks of rivers and of squares redevelopment, both to remedy the phenomenon of “heat island” with solutions for urban green areas, permeability of soils, and to favor the flow of water into case of floods [39,40].

The “urban green system” is a heritage of the complex city, which requires careful assessment that considers not only the economic variable, but also the social, environmental and institutional ones. The proposals for investments in GI, their management and the evaluation of benefits will have to be shared by the community, for an effective pursuit of the objectives set. An assessment that considers the dimensions of sustainable development, which will contribute to providing useful elements for the promotion of a model of governance of the city eco-social-green.

The “urban green system” can therefore take on the role of an instrument for redevelopment, continuity and integration between building renovation and natural and agricultural environments, creating and integrating ecological corridors or networks on a larger scale. Furthermore, it can contribute to reducing the vulnerability of the urban system through the fundamental ecosystem services (ecosystem services can be considered as flows from natural capital stocks, and most of them are indispensable for human life and nature itself: according to Costanza [41] “... they consist of the flows of matter, energy and information coming from the stocks of natural capital, which are combined with the services of anthropogenic artefacts to generate well-being and quality of life ...”) offered, which perform the following functions:

- (1)

- environmental-regulator

- (2)

- hydrogeological protection

- (3)

- social, recreational and therapeutic

- (4)

- cultural and educational

- (5)

- aesthetic-architectural

Examples of green urban infrastructures are green spaces and multifunctional wetlands, green roofs and walls, urban gardens, agricultural areas and periurban forests, cycle and navigation routes with environmental functions and SUDS (Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems) such as permeable covers, draining trenches, etc. According to the European Commission, 2013, urban agriculture helps to improve the GI of cities, as:

- -

- it provides products (food, fiber, and biomass).

- -

- it generates new services (employment and investment, tourism and recreation, health and well-being education, social services, educational services, and therapeutic function).

- -

- it regulates ecological services (climate, water, land management, and disaster prevention).

- -

- it maintains biodiversity.

Intelligent and sustainable cities (smart cities) take the leading role in mitigating and adapting to climate change, limiting energy consumption, saving water and natural resources and designing a soft and sustainable mobility, capable of using GI to restore continuity to natural networks and make a growing contribution to the protection of biodiversity.

GI therefore become an important tool of action for climate adaptation, for the enhancement of ecosystem services and biodiversity, and for social cohesion [42,43,44,45] in the model of a sustainable city of the future.

Green Infrastructures, according to the Community definition, “... are networks of natural and semi-natural areas planned at strategic level with other environmental elements, designed and managed in such a way as to provide a wide spectrum of ecosystem services. This includes green (or blue, in the case of aquatic ecosystems) and other physical elements in areas on land (including coastal areas) and marine areas. On the mainland, Green Infrastructures are present in a rural and urban context...” [46]. Without interruption, the network of GI penetrates the entire territory, creating continuity, functionality and eliminating barriers and waste. Nature, no longer reduced to an object of consumption and of only aesthetic enjoyment, recovers and puts at the center the role of supplier of vital resources and balancing of global stability and sustainability.

Green infrastructure is a new term, but it is not a new idea. It has roots in planning and conservation efforts that started one hundred fifty years ago. Green infrastructure has its origin in two important concepts: (1) linking parks and other green spaces for the benefit of people; and (2) preserving and linking natural areas to benefit biodiversity and counter habitat fragmentation.

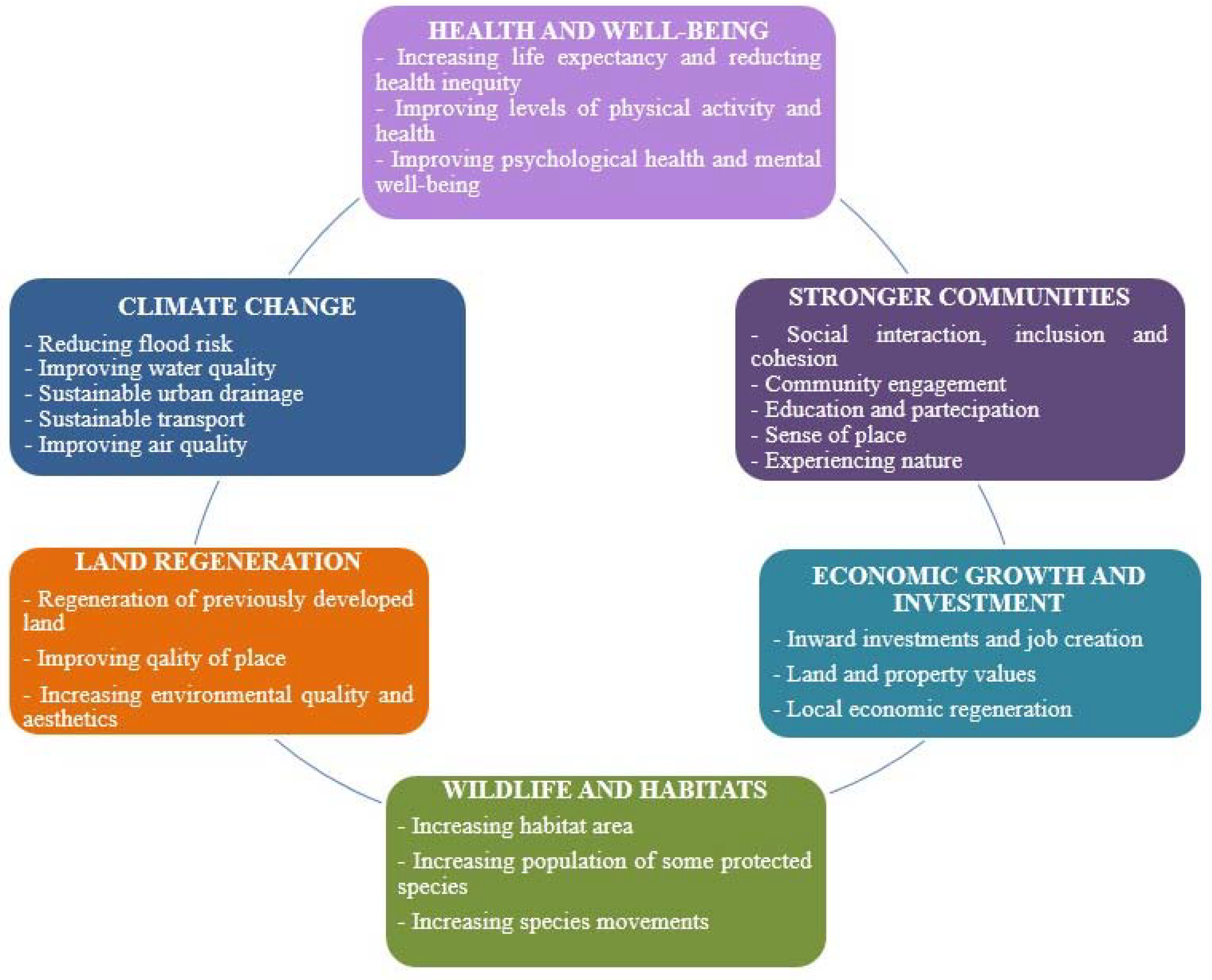

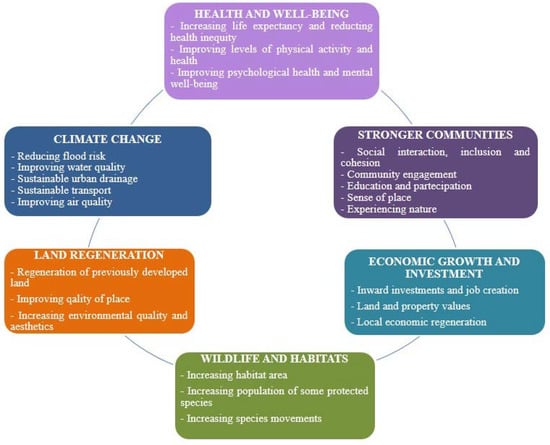

The implementation of GI promotes an integrated approach to land management, determines positive effects under the aspect: economic, in the containment of some of the damages resulting from hydrogeological instability; environmental, in the fight against climate change and in restoring the quality of environmental matrices (air, water, soil); and social, in promoting the well-being of citizens and their social relations and promoting social inclusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Benefits of green infrastructures (adapted from Forest Research, 2010).

The adoption of GI is an important step in the EU 2020 strategy on biodiversity which, by that date, foresees that ecosystems and their services are maintained and strengthened through GI and the restoration of at least 15% of degraded ecosystems [47].

The EU regulatory guidelines on climate change and the role of GI, on the one hand, and new forms of collaborative governance, on the other hand, are leading to a new model of climate resilient city [20,37,48]. To pursue this objective, it will be fundamental to propose a model of multidimensional evaluation and management of investments in sustainable GI shared by the involved actors.

4. Green Infrastructures in the World and Situation in Italy

There are many GI projects in an advanced state of realization in the world [39]. This is the case of the British Green Belts, which in urban planning in the UK are the policy tool to guarantee the ecosystem functions of the territories, to control urban expansion and to protect landscapes.

Spain has also implemented initiatives in many areas: this is the case, for example, of the Anella verda of Barcelona which includes a network of 12 protected areas around the city connected by increasingly enhanced ecological corridors. GI around cities play an important role in regulating urban sprawl, regulating urbanization and the growing senseless land consumption.

We can mention many other examples such as Territorial Planning in the metropolitan area of Lisbon, as well as numerous urban GI projects in the United States, affected by unprecedented climatic phenomena. For example, in Nagoya, Japan, the average temperature of the city has risen by about 2.7 °C in the last 100 years.

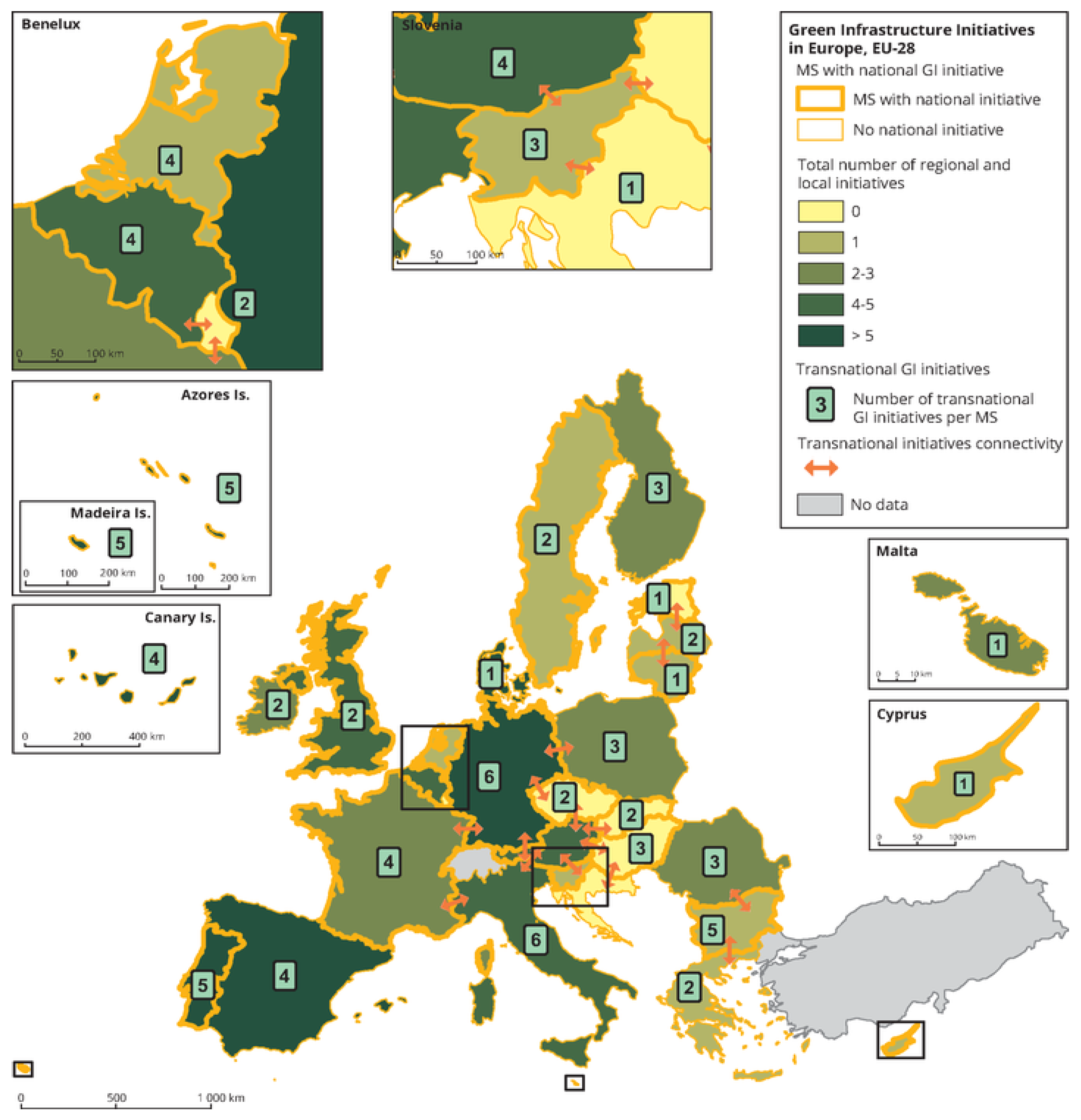

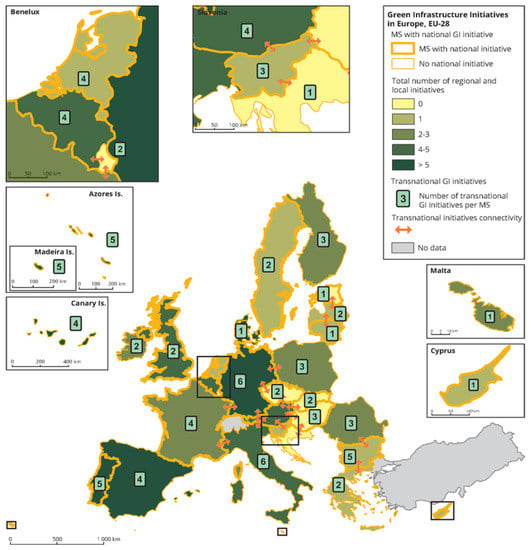

At European level, a picture of GI deployment is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Green Infrastructures initiatives in Europe, EU 28 (EEA, 2017).

In Italy the GI are still few, limited to individual local initiativesand in any case are not included in a system logic, essential for achieving the objectives. (In Italy, very few and isolated are the cases of realization of similar initiatives on the territory. Apart from the well-established Green Belt in Turin, we mention the green ring of the municipality of Mirandola (Modena) (envisaged for the objectives of the local energy plan). Other initiatives are Piazza Gae Aulenti in Milan and a few others scattered.) From the point of view of the planning process, a strength of our country is the large and consistent work on ecological networks that have contributed to an important work of mapping the territorial potential, drawing on a very detailed scientific knowledge of the great wealth of habitats present throughout the peninsula. The planning of an ecological network has now provided almost all provinces, many regions and some municipalities. The ecological networks include the great wealth of the Protected Areas and the Natura 2000 Network, which in fact constitute a large GI on the territory, integrating them in the territorial planning.

The attention to the presence of green in urban areas, in its various forms and functions, has been growing in recent years, so much so that even at the regulatory level several laws have been promulgated on the subject. Among them, the Law 14 January 2013, n. 10 Rules for the development of urban green spaces, in which the functions of urban green are recognized:

- -

- Ecosystem services: Positive effects on the local climate, on air quality, on noise levels, on soil stability are evident, and biodiversity conservation.

- -

- Socio-economic aspects: Meet the needs for recreation, social relations, cultural and health growth of its inhabitants.

In addition, other measures have recognized the role of social agriculture (Law No. 141 of 18 August 2015) and actions to recover degraded areas and buildings, both for social purposes and to reduce land use (by responding to the directive Community to reach 0% land use by 2050).

Despite the multiple benefits associated with Green, the situation on a national scale still shows some critical issues. The picture that emerges is that of a country where urban green is mainly managed on a technical and prescriptive level rather than as a strategic resource to orient local development policies to quality and resilience. Every inhabitant has an average of 31.1 square meters of urban green (the picture of urban green per inhabitant (m2 per inhabitant) in other European cities is as follows: Paris, 8; Zurich, 10; Copenhagen, 12; Amsterdam, 20; Leningrad, 26; Munich, 30; and Stockholm, 100). The highest endowments are found between the cities of the northeast (50.1 square meters), more than double those of the center, the northwest and islands. The southern average (42.5 square meters per inhabitant) is affected by the high availability of the Lucanian capitals. In 17.2% of the cities, the per capita budget is equal to or greater than 50 square meters per inhabitant, while in 16.4% the threshold, set by the standard, of nine square meters per capita is not reached. Urban gardens are constantly growing in cities, activated in 64 administrations in 2015 (+5.0% compared to the previous year) (ISTAT).

The good functionality and the correct use of the public green areas require the support of multi-criteria evaluation tools and specific government tools, able to guide the administrators in the choices of planning of the green investments and management as well as to provide citizens with elements of knowledge and respect towards this important common good [49,50].

The success of a particular public green space is not solely in the hands of the architect, urban designer or town planner; it also relies on people adopting, using and managing the space. People make places, more than places make people [42,43].

In the literature, different approaches have been reported that are used as possible models of governance, which provide for levels of interaction between the stakeholders interested in climate adaptation initiatives, in particular between municipalities and citizens. Their analysis led to highlighting important points to consider in the development of governance and evaluation models, specific for local needs. In particular, the four strategic issues are:

- -

- Proactive citizens engagement: It is necessary to create and sustain citizen engagement and ownership; collaborative approaches in adaptation actions and green infrastructures projects can be more useful [51].

- -

- Equity approach: It is important to consider residents of diverse housing types and also socio-economically disadvantaged groups; the municipal adaptation and GI planning should support and engage disadvantaged people [52].

- -

- Nature based approach: It is more publicly acceptable because this approach provides added value in terms of recreation and social spaces [53,54]. Then, it can allow citizens to contribute both individually (private gardens) and collectively (urban farming groups) [55,56,57,58].

- -

- Systematic adaptation mainstreaming: Citizen–municipality interactions require changes in municipal organization and in departmental coordination [35].

Urban greening is inherently a multivariate venture that demands the integration of knowledge from different expertise and disciplines. The urban green project could be valued by using a multidimensional approach that includes the global value of the project from the interconnected dimensions of sustainable development (economic, social and environmental).

5. The Evaluation of Investments in GI According to an Eco-Social-Green Model: The Case Study of Catania

The city of Catania is the second city, in terms of importance, surfaces and inhabitants of the Sicily Region with an area of 180,000 m2, about 350,000 inhabitants and a density of 1.7 inhabitants per square meter. Under the urbanistic aspect, in the Municipality of Catania, there is a Regulatory Plan, drawn up in 1964, designed for socio-economic needs of a company of the 1960s, where the priorities and the vision were completely different from the current ones, mainly in terms of environmental protection, attention to climate change and social inclusion. In relation to the socio-economic development that the city has had, for the future potential of the “urban green system”, the municipal administration has planned a program of interventions in line with climate adaptation measures [19,49,50].

In the city of Catania (Km2 183), the extension of the urban green is equal to 4,843,660 square meters, and the urban green per inhabitant corresponds to 16.4 square meters. The “urban green system” consists of the following types:

| The “urban green system” of the city of Catania (*) | ||

| Green typology m2 | ||

| • | Urban Parks (>8000 square meters) | 513,577 |

| • | Green Equipment. (<8000 square meters) | 431,270 |

| • | Urban Design Areas | 715,500 |

| • | Urban Forestation | |

| • | School gardens | 350,000 |

| • | Botanical Gardens and Vivai | 20,000 |

| • | Zoological Gardens | |

| • | Cemetery | 50,000 |

| • | Urban Gardens (mainly managed by families) | 2500 |

| • | Sports areas/Outdoor play | 100,000 |

| • | Bosch areas (>5000 sqm) | 972,769 |

| • | Uncultivated Green | 1,688,044 |

| Total Urban Green | 4,843,660 | |

(*) Source: Directorate for Environmental and Green Policies and Energy Management of the Autoparco—Service for the Protection and Management of Public Green, Giardino Bellini and Parchi, 2017.

The green areas in the municipal territory play an important specific role both as an urban component, for the conservation and improvement of the landscape and the environment, and as a means for aggregative purposes for social and cultural integration.

In the implementation of GI, projects that, in compliance with Legislative Decree No. 50/2016, aim to achieve several objectives, include:

- improving and preserving the local landscape and environmental restoration;

- favor urban climate control and reduction of albedo and heat islands;

- increase the naturalness and biodiversity of the urban territory; and

- stimulate the aggregative, social and therapeutic functions of green areas (e.g., urban gardens, neighborhood parks, healing gardens, spaces for cultural events and shows) (Regulation of the public and private Green of the city of Catania, 2017).

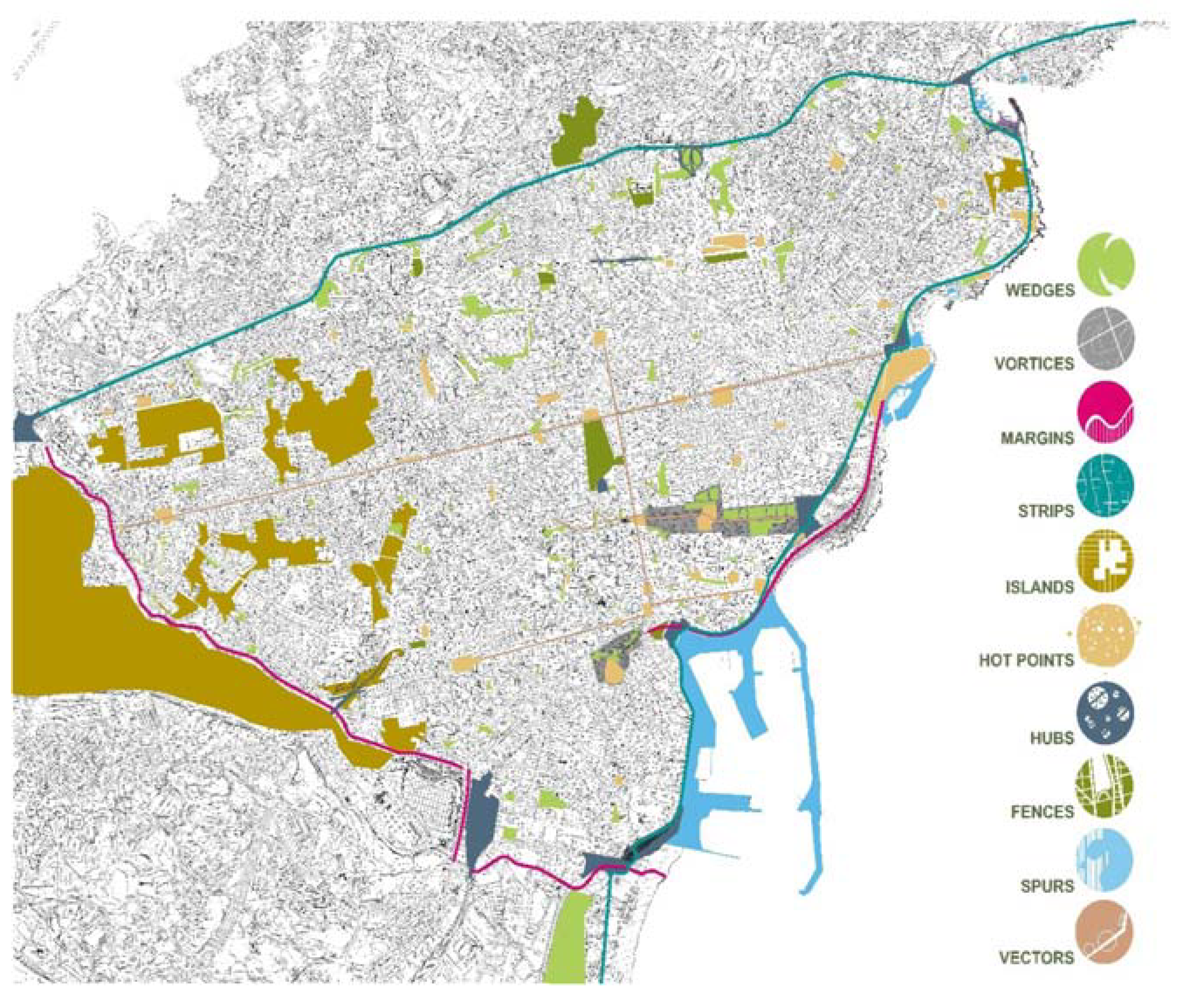

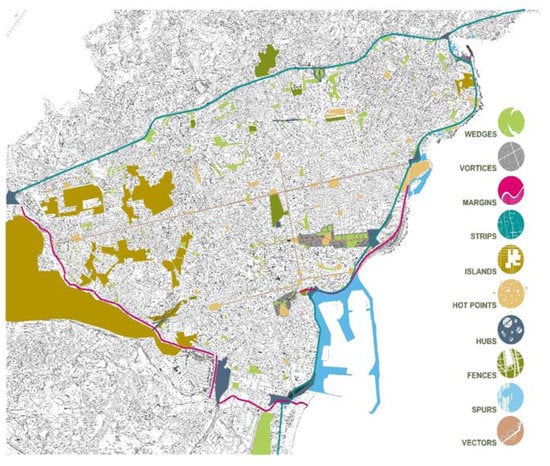

The Municipality of Catania proposed a development strategy for GI interventions that adopts the LID (Low Impact Development) methodology [59]. The approach includes the creation of green areas, green avenues, wetlands and urban gardens according to the classification: Wedges, Vortices, Margins, Strips, Islands, Hot points, Hubs, Fences, Spurs and Vectors (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The types of Green Infrastructures foreseen in the municipality of Catania (2017).

Wedges are urban areas with a significant surface, with the aim of becoming green areas dedicated to developing the relationship between citizen and city. Vortices represent a model of areas designed to interact with the city with an inaccurate destination, which can adapt to the different needs of different groups of society (children, young people, families, adults, retirees, etc.). The destination of these areas varies over time according to the trends and needs of the city, even with an interdependence between them. The areas defined Margins under the environmental, climatic and social aspects represent a bit of a breakthrough, as the boundary criterion of the city is redefined, moving it ever more towards the areas that assume a strategic significance under the aspect of livability (Sea, Rivers, Mountain, and Parks). In this vision of development, therefore, the synergies between the oriented reserve of the Simeto Oasis, Etna Park, and in general with the urban parks (Playa del Bosco, Gioeni Park, etc.) and the city are included. Strips represent areas dedicated to the connection structures between the different areas of Catania, also in relation to the redefinition of the above-mentioned margins. Island areas allow giving back to the territory its centrality, where man has included the buildings over the years. The project therefore envisages the creation of paths between the different areas not built to make appear the anthropogenic effect of man as the generation of islands immersed in the sea, which is specifically represented by the territory. Hot spots are red areas, under the cultural, economic and social aspects in which the interests of a large part of society are concentrated and in which a mitigating action is needed to improve the quality of the environment. Transport hubs such as Railway Station, Port, and Airport represent the areas where resident population flows, tourists and population that gravitate around the city with both structural and infrastructural needs. In these areas emerges the need for both congestion and pollution generated to create buffer areas to mitigate the effects of the Hubs present in the area. Spurs are the areas that correspond with the Waterfront project, which start from the port and end up in Ognina, where the city has to reappropriate these spaces to encourage the development of a tourist town on the sea. Finally, in the areas defined as Fences, all the defined and delimited green parks are included.Vectors include the areas that represent the main routes of the city’s traffic.

Based on an eco-social-green model, it will be possible to carry out a social, environmental and economic assessment of the proposed interventions, through a collaborative process and sharing the objectives of valorization, transformation and redefinition of the green spaces of the city of Catania. The model proposed is called eco-social-green because we have decided to integrate the aspects that we consider important for the new role attributed to cities. In fact, both at European level and in the scientific debate, there is an increasing attention to the role that cities must have on climate change, biodiversity, conservation and promotion of social cohesion. A multidimensional approach allows making decisions in complex conditions and it gives the possibility to consider economic and non-economic dimensions; the existing synergies and possible conflicts, the differentviewpoints of the subjects involved (public and private).

6. Methodology

The case study analysis evaluated the GI planning of the metropolitan city of Catania, to experiment new approaches and opportunities for the definition of green strategies that have found concrete applications in the development of guidelines and best practices, in politics and local planning tools, as a tool for climate mitigation in an urban environment.

The proposed approach is based on the integration between the participatory planning (based on the establishment of the Focus Groups with the various stakeholders) and NAIADE method (Novel Approach to Imprecise Assessment and Decision Environments [18], for the Multi-Criteria Social Assessment (SMCE)) as possible methodological structure to acquire and evaluate the “complex” information collected (quantitative and qualitative data) on possible alternative scenarios in relation to the urban green spaces.

The methodology can be considered a social experiment, able to produce collective opinions, to detect communication barriers, to study conflictual behavior, to acquire local information, and to create acceptable options [37,38,45,48].

The innovative advantage is the interaction among the participants that highlights their being fundamental tools to support a process of evaluation and reciprocal learning. This approach allows revealing new visions of the subjects involved to have a final participated decision.

The target is that of developing a methodological structure made by suitable tools to acquire first, and process second, qualitative and quantitative information concerning the possible alternative scenarios of the problem under study. Opinions were collected at specific meetings at local level with stakeholders and sector’s operators involved into the issue from environmental, social, climate, landscape, health safety and economic points of view.

The opinions have been collected through specific meetings with local stakeholders, operators and citizens, interested in the issue in question from different economic, social and environmental aspects [60]. The method of collecting data through the focus groups has seen the presence of two researchers, one with the role of moderator and the other with detector of the responses of the individual subjects involved.

This is an approach whose adoption is limited to problems of territorial planning referable to SMCE [61,62,63], while there are more numerous articles that employ SMCE for the resolution of problems related to the management of environmental resources, and in general, to valuations of sustainability, climate adaptation, energy policy, etc. [64,65,66,67]. The economic evaluation of the benefits associated with the selected and shared interventions (which is been reported here to present the decision-making innovation but which is an integral part) can be carried out by adopting the estimation procedures already widely applied for environmental resources, based on the specific resources and purposes considered (e.g., [68,69,70,71,72,73,74]).

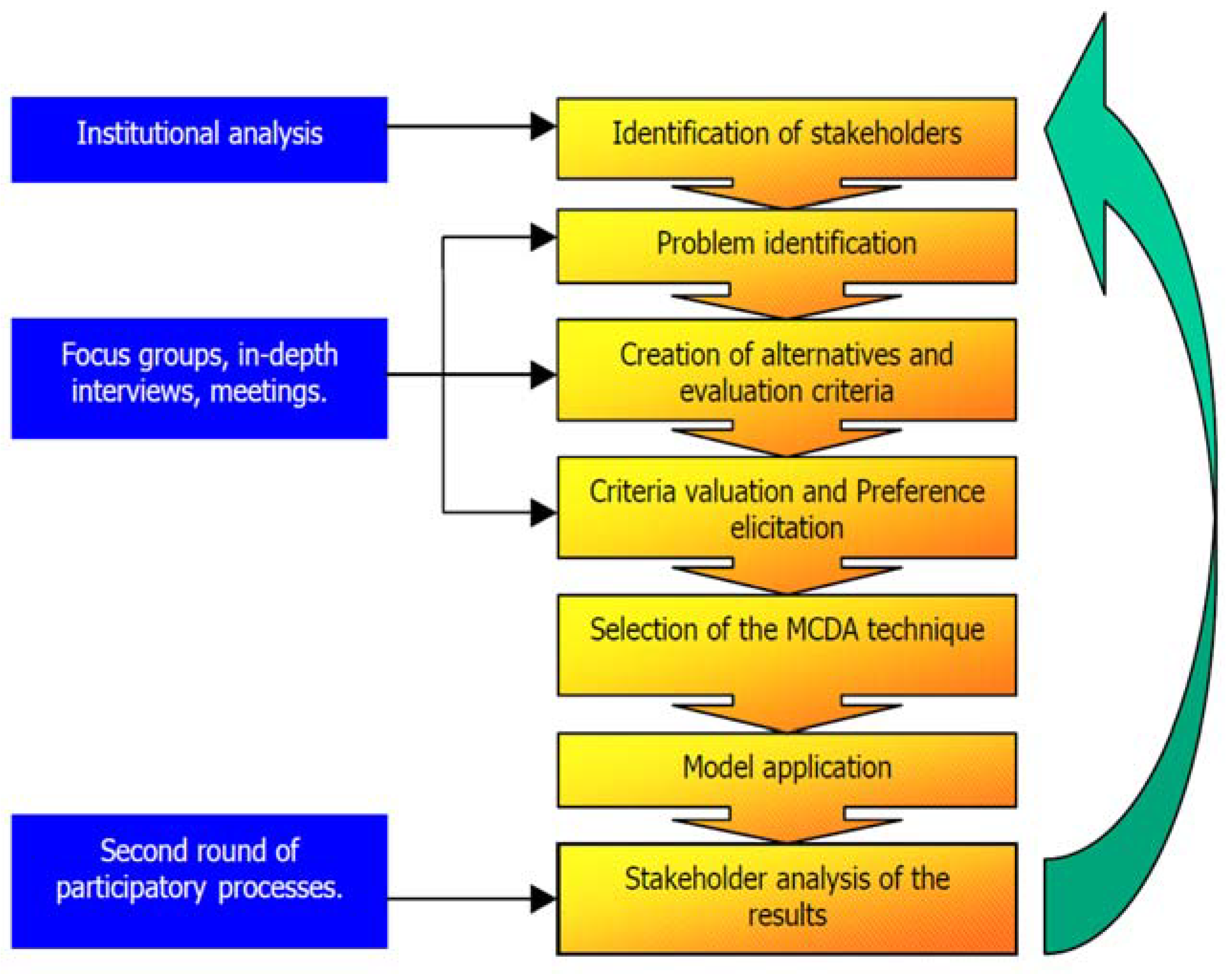

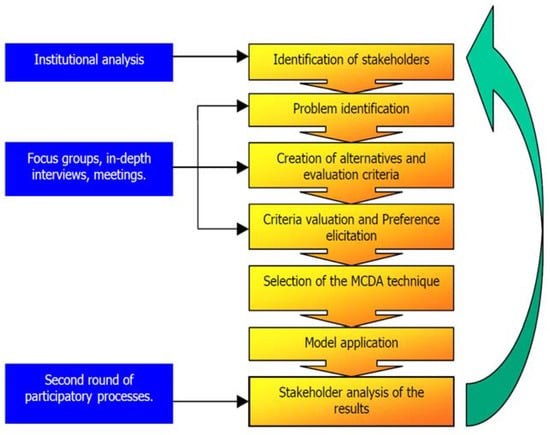

Figure 4 identifies the steps on which our SMCE is based, with some adaptation in relation to the specificity of the context surveyed.

Figure 4.

Structure of the model SMCE.

In detail, the proposed model is based on:

- the individualization of the citizens and of the stakeholders involved (100 questionnaires);

- the definition of the alternative scenarios (definition of the three hypotheses of scenario: social, green and city);

- the definition of the context of evaluation, namely the decisional criteria (urban green spaces of Catania for shared project);

- the evaluation of the impact of alternative scenarios relative to the criteria in question); and

- the final creation of the impact matrix.

The structure used focus groups as a social research methodology, aimed at acquiring the opinions of stakeholders regarding a variety of scenarios of future development within the zone examined. The choice of focus groups and, therefore, of the interaction among the actors involved, aimed to support the phase of the choice and evaluation of the different aspects that were included in the equity matrix. The matrices of impact and equity constitute the basis for the use of the discrete multicriterial evaluation NAIADE model [75], able to manage qualitative and quantitative data to evaluate the measures of intervention. This instrument supports the classification of the alternative scenarios proposed on the basis of determined decisional criteria and considerations of possible “alliances” and “conflicts” between the groups of stakeholders on the proposed scenarios, thus measuring their acceptability. The NAIADE multicriterial evaluation method applied to this study constitutes a discrete method of evaluation capable of managing qualitative and quantitative data. It is an appropriate tool for the planning of problems characterized by great “uncertainty” and “complexity” regarding existing territorial, social, and economic structures and their interrelations [76]. The basic input in the NAIADE method consists of: alternative scenarios to be analyzed, different decisional criteria for their evaluation, and different stakeholders who express opinions about the scenarios in question. One of the strengths of this tool in the application to the planning of interventions on green spaces is based in its ability to collect the conflicting perspectives of the stakeholders and to address the compromises among the environmental, social and economic dimensions.

In relation to the objective of this study, the analysis was applied to the principal priorities, the methodology used for the definition of the model of management for the Green area of Catania, which is the area of investigation for this work.

The evaluation through the Focus Groups was divided into three phases, referring in the specific case to the destination of urban areas in a degraded state to be valorized:

Phase 1 consists of “planning” the meetings. During this phase, the following were established:

- -

- the number of sessions and the time dedicated to each of them (eight, as an expression of the individual categories considered, association of citizens, groups of pensioners, cultural associations, playrooms, trade unions, public institutions, scientific groups, and tertiary sector’s companies, with a length of 4–8 h);

- -

- the creation of an interview guide to conduct the discussion (scientific and dissemination materials, research papers, photos, maps, the relative problems of urban green areas and on the social and climatic effects derived from them);

- -

- the selection of participants (stratified selection for homogeneous groups: age, gender, and income).

The questionnaire used for the interviews was designed to explore the perception of environmental issues in the urban context and to evaluate the real needs of the population in terms of environmental quality and fruition of public green spaces. It included 10 questions to collect information and opinions useful for the research, on the three hypotheses proposed: social, green and city.

- -

- Hypothesis 1—SOCIAL: creation of green areas with a social function (equipped parks, urban gardens, etc.).

- -

- Hypothesis 2—GREEN: creation of urban green areas with non-usable landscape function.

- -

- Hypothesis 3—CITY: conservative recovery, cleaning and maintenance of the current green.

Phase 2 consists of “carrying out” the entire activity, based on the guide to the pre-established interview. It began with the presentation of the topic relating specifically to the action strategy for the management of degraded areas to be recovered, using the support material (articles, results, and photographs), prepared specifically to introduce the issue under consideration and stimulate discussion and the interaction of the participants. During this phase, various ideas and opinions were acquired that represent the reactions of the participants involved in the issues raised.

Phase 3 consists in the elaboration of the “qualitative results” and in the production of the final report.

In this regard, various qualitative analysis tools were used, based on intentionally prepared inputs and specific rules. Overall, the Focus Groups can be considered social experiments, able to produce collective opinions, reveal communication barriers, study conflicting behavior, acquire local information, create acceptable options, synthesize information, etc. The key advantage of the Focus Group dedicated to defining intervention strategies in green urban areas to be enhanced, compared to other participatory techniques, lies in the deep interaction between the participants, becoming a “social network”. The participants become fundamental tools to support a “mutual learning process” on the question examined. This participatory comparison technique makes it possible to reveal new dimensions of the issue under discussion, thus underlining the possibility for the Focus Group to bring out the opinions in this regard rather than produce generalized results. The analysis phase of the results of the Focus Groups is followed by the multi-criteria analysis where the basic input of the NAIADE method consists of: alternative scenarios to be analyzed, different decision criteria for the relative evaluation and different stakeholders that express opinions on the scenarios in question. Based on this method, two types of analysis can be performed:

- -

- a multi-criteria analysis, which, based on the impact matrix, leads to the definition of the priorities of alternative scenarios with regard to certain decision-making criteria;

- -

- an analysis of equity, which, based on the equity matrix, analyzes possible “alliances” or “conflicts” among different interests in relation to the scenarios in question.

In this regard, the multicriteria analysis, according to the NAIADE methodology, aims to classify alternative scenarios based on the preferences of individual groups based on certain decision criteria [77,78,79,80].

The basic input of the NAIADE method is constituted by the impact matrix (criteria/alternative matrix), including scores that can take the following forms: crisp numbers, stochastic elements, fuzzy elements and linguistic elements (such as “very poor”, “poor”, “good”, ”very good”, and “excellent”) [18]. To compare alternative scenarios, the concept of distance is introduced. In the presence of crisp numbers, the distance between two alternative scenarios with respect to a given evaluation criterion is calculated by subtracting the respective crisp numbers.

The classification of alternative scenarios is based on data from the impact matrix, used for:

- -

- comparison of each single pair of alternatives for all the evaluation criteria considered;

- -

- calculation of a credibility index for each of the aforementioned comparisons, that measures the credibility of one preference relation, e.g. “alternative scenario ‘a’ is better/worse, etc. than alternative scenario ‘b’” (preference relationships are used);

- -

- aggregation of the credibility indices produced during the previous stage leading to a preference intensity index μ* (a, b) of an alternative “a” with respect to another “b” for all the evaluation criteria, associated the concept of entropy H* (a, b), as an indication of the variation in the credibility indices;

- -

- classification of alternative scenarios on the basis of previous information.

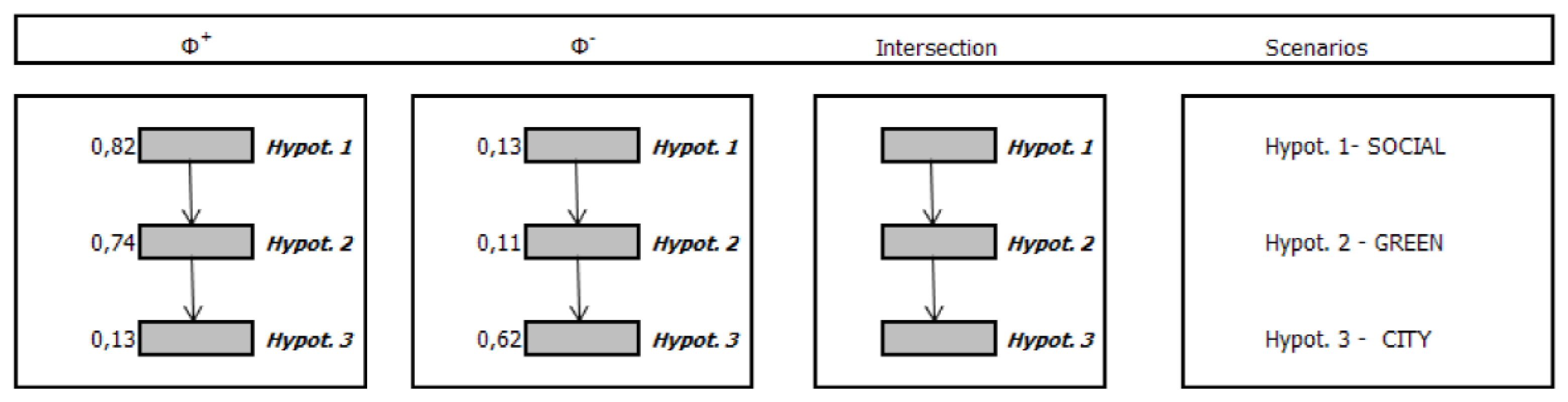

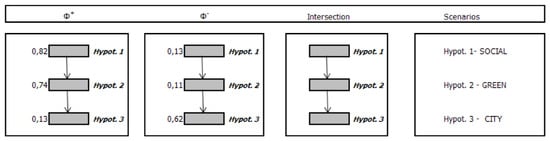

The final classification of the alternatives was the result (intersection) of two different classifications: the classification Φ+ based on the “best” and “decidedly better” preference relationships; and the classification Φ− which is based on the “worst” and “decidedly worse” preference relationships.

In relation to the objective of the present study, the analysis was applied to main priorities, for the evaluation of the optimal management model for the enhancement of the green areas of Catania.

7. Results and Discussion

The results of the present work provide a first multidisciplinary contribution to research on the management and planning of green areas in cities. Specifically, the analysis was conducted on the basis of a question:

What are the strategies for the recovery and enhancement of degraded urban areas of the City of Catania?

Three hypotheses of green recreate strategies are envisaged (Table 1):

Table 1.

Three hypotheses of alternative scenarios of green recreate envisaged the City of Catania.

To evaluate the three hypotheses mentioned above, evaluation criteria have been defined, which represent “a measurable aspect of judgment that can characterize a dimension of the various choices that are taken into consideration” [81].In the present case study, twenty evaluation criteria or variables were used. These criteria were defined on the basis of the purpose and objectives of the evaluation of the analyzed case, which can be considered representative of the reality of the City of Catania but overall very similar to other metropolitan areas.

The objectives of the evaluation activity are: Environmental, Social, Climate, Economic, Landscaping, and Health and safety.

Specifically, for each objective, the related evaluation criteria are considered (Table 2):

Table 2.

The objectives and the evaluation criteria adopted in the applied model for the Urban green areas of Catania.

According to the above-reported indicators, the overall impact matrix results are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Evaluation of the results of the impact matrix of the various alternatives.

The Hypothesis Social is considered the most shared scenario (highlighting the social, landscape and economic aspects), followed at short distance by the Hypothesis Green (highlighting environmental, climate, landscape results), while the Hypothesis City is placed at the end of the preferences (with more negative evaluation).

Then, the equity matrix was developed. It provided stakeholders’ opinions on the three hypotheses suggested. The selection of stakeholders was based on their potentialities to influence the targets of the project. The stakeholders here included representative citizens, socially vulnerable groups and different interested associations and possible users of the interventions, with different qualifications, in both private and public sectors. In particular, eight typologies of stakeholders were involved: association of citizens, groups of pensioners, cultural associations, playrooms, trade unions, public institutions, scientific groups, and tertiary sector’s companies. It is important to underline that stakeholders’ opinions in the NAIADE model can only be of a quality kind: language expressions from very poor, poor, medium, good, very good, and excellent (Table 4).These results show that many stakeholders and operator groups selected agreed with the evaluation of the three hypotheses.

Table 4.

The equity matrix: stakeholder opinions on the three hypotheses.

The results of the multi-criteria analysis, i.e., the evaluation of the three intervention hypotheses, highlighted that Hypothesis Social is the predominant hypothesis, followed at short distance by Hypothesis Green, while Hypothesis City gained a marginal meaning (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Classification of alternative hypotheses with multicriteria evaluation (source: our elaboration and data collected directly from the survey).

The results obtained through the equity analysis were used to examine possible alliances or conflicts among the opinions of stakeholders about the decision of what hypotheses to adopt. Results in Table 5 show the value relative to the classification of the scenarios corresponding to the higher consensus level. These results show that many stakeholders, besides agreeing on the classification of the different hypotheses to apply, agreed with Hypothesis Social.

Table 5.

Classification of the scenarios corresponding to the higher consent (0.8423).

The efficiency of this kind of approach relies on the possibility of establishing a “learning platform” that eases participation, information exchange and reciprocal comprehension of participants, who stimulate each other towards a sharing of the territory. Results allowed including several perspectives of the evaluation problem under study, as demonstrated by the different groups involved, increasing perception of planners about the acceptability of the alternatives proposed that may lead to improving the strategic decisions and, thus creating innovative ideas and new planning solutions, based on the possibilities offered by the participated processes.

Overall, the results obtained from this model of collaborative governance, eco-social-green, developed through the integration of a participative tool and a multi-criteria analysis, become strategic for the choices of urban investments, in particular related to GI, shared with the community.

8. Conclusions

The new guidelines on the protection of natural capital and biodiversity and attention to climate change are laying the foundations for outlining new ways of government of the territory and of the cities, by an approach proactive and engaging the citizens. Cities are ecosystems full of human presence, rich in knowledge and innovation, which welcome more than 50% of the world’s population and about 70% of the Italian population. In cities, the conflict between artificiality and naturalness is maximum and causes loss of biodiversity, quality of ecosystem services and resilience [82].

A direct consequence of the variety of expected impacts in urban settlements is the multiplicity of institutional actors who, together with citizens, must be involved in adaptation policies. For actors who have responsibility at different territorial scales (state, regions, provinces, and municipalities) or sectors (basin authorities, energy service management bodies, water companies, etc.) and citizens, a multilevel governance is required.

This research allowed pointing out that the methodological approach adopted, which is inspired by a model of city eco-social-green, based on the integration between the participated planning technique and the multi-criteria analysis, in the case of problems linked to the “urban green system”, represents a strategic tool. The limit linked to the non-complete evaluation in economic terms is recognized, which can be performed simultaneously or at a later time, using the specific estimation procedures for the economic evaluation of environmental resources, based on objectives, specificity of the environmental and territorial resources considered and financial resources available. The model allowed individualizing possible alternative scenarios and shared solutions in relation to the “complexity” of the subject that is characterized by the social, economic, environmental, landscape, health safety and institutional implications. The specific operative implications, evaluated in this work, deriving from the application of the different hypotheses, showed that an ex-ante evaluation allows proposing of a sustainable model to the system avoiding the intervention strategies that do not fit to the sector dealt here. The efficiency of this model of evaluation relies on the possibility of establishing a learning platform that facilitates the participation, information exchange and reciprocal comprehension of the participants that support a strategy for the development and the fruition of the “urban green system” of the city.

The results of the multi-criteria analysis, i.e., the evaluation of the three intervention hypotheses, highlighted that Hypothesis Social is the predominant hypothesis, followed at short distance by Hypothesis Green, while Hypothesis City gained a marginal meaning.

The results show that many stakeholders, besides agreeing on the classification of the different hypotheses to apply, agreed with Hypothesis Social, i.e. the creation of green areas with a social function (equipped parks, urban gardens, etc.). The social aspect of public green spaces plays an important role in the choice of the scenario and in the evaluations of the subjects involved. The public green spaces are of importance because they offer the opportunity for high levels of interaction between persons of different social and ethnic backgrounds [44,45].The research highlighted the relationship between the citizen and environmental phenomena in the urban field, noting an interesting and critical perception of the problem in question. Through the processing of the data emerged from the survey, cognitive elements were acquired to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the intervention proposal, based on concrete adaptation actions, which considered the promotion of the identity of the places and of local ecological knowledge. It has also been noted that, although the benefits of green for the urban environment, climate and quality of life are now recognized, their role in urban planning appears to be still marginal and the active participation of citizens in sharing and benefit evaluation is still limited.

The approach on which NAIADE is based—scarcely still used in evaluations linked to the benefits related to the ecosystem services of urban green spaces—seems more suitable to deal with problems of choice linked to green spaces, for which we must consider non-negotiable objectives (ecosystem protection and social functions), which sometimes are in conflict with short-term requests by interested parties. As other studies have indicated [83,84,85], our study highlights an interesting potential for a wider use of SMCE in the governance of green space, for its ability to integrate ecological, social and economic values, as well as the different stakeholder preferences among social groups, places and temporal dynamics. Of course, policy makers have a broad ability to improve human well-being in cities through green space governance approaches that take into account their different components: economic, environmental and social. To date, especially environmental and social ones are often scarcely considered in the political processes that characterize the governance of green space in cities.

Results allowed including several perspectives of the evaluation problem under study, as demonstrated by the different groups involved, increasing perception of planners about the acceptability of the alternatives proposed that may lead to improve the strategic decisions and, then, create innovative ideas and new planning solutions, based on the possibilities offered by the participated processes.

This work in its project proposal offers a series of ideas, suggestions and recommendations aimed at introducing measures for adaptation to climate change in urban planning instruments and promoting innovative choices that can be useful for Public Administrations and technicians in the sector, in the promotion of GI, starting from the already available assets, be it public or private. To date, however, the prospects for development of the GI are strictly dependent on its inclusion in planning policies, which local authorities and urban planning regulations must provide and support financially as well.

Ecosystem services must be integrated into the planning and the choices of urban planning policies [86], making GI and eco-innovation the fulcrum of an intelligent and sustainable urban transformation towards a new model of sustainable city enhancing biodiversity, environment and social inclusion.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This research was funded by “Fondo: Piano per la ricerca dipartimentale 2016–2018”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations. Revision of the World Urbanization Prospects; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jim, C.Y. Planning strategies to overcome constraints on greenspace provision in urban Hong Kong Town. Plan. Rev. 2002, 73, 127–152. [Google Scholar]

- Radovanović, M.; Lior, N. Sustainable economic–environmental planning in Southeast Europe—Beyond-GDP and climate change emphases. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, A.; Sturiale, L.; Bellia, C.; Foti, V.T.; Timpanaro, G. The redefinition of the role of agricultural areas in the city of Catania. Rivista di Studi sulla Sostenibilità 2016, 2016, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, A.; Sturiale, L.; Bellia, C.; Foti, V.T. Timpanaro, G. The redefinition of the role of agricultural areas in the city in relation to social, environmental, and alimentary functions: The case of Catania. Rivista di Studi sulla Sostenibilità 2017, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Monclús, J. From Park Systems and Green Belts to Green Infrastructures. In Urban Visions; Díez Medina, C., Monclús, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hestmark, G. Temptations of the tree. Nature 2000, 408, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anguluri, R.; Narayanan, P. Role of green space in urban planning: Outlook towards smart cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 25, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y. Green spaces preservation and allocation for sustainable greening of compact cities. Cities 2004, 21, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.E.; Handley, J.F.; Ennos, A.R.; Pauleit, S. Adapting cities for climate change: The role of the green infrastructure. Built Environ. 2007, 33, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzoulas, K.; Korpela, K.; Venn, S.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.; Kazmierczak, A.; Niemelä, J.; James, P. Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using green infrastructure: A literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 81, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, andenvironmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.; Lowe, A.; Winkelman, S. The Value of Green Infrastructures for Urban Climate Adaptation; Center for Clean Air Policy: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, E.; Aalders, T.; Ádám, D.; Feller, R.; Henselek, Y.; Hoffmann, A.; Ibe, K.; Matthey-Doret, A.; Meyer, M.; Negrut, N.L.; et al. Cascades of green: A review of ecosystembased adaptation in urban areas. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 36, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broto, V.C.; Bulkeley, H. A survey of urban climate change experiments in 100 cities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulkeley, H. Cities and the governing of climate change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, A.; Watkiss, P. Climate change impacts and adaptation in cities: A review of the literature. Clim. Chang. 2011, 104, 13–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munda, G. Multicriteria Evaluation in a Fuzzy Environment—Theory and Applications. In Ecological Economics; Physica-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Fifth Assessment Report. Climate Change 2014. Mitigation of Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Voskamp, I.M.; Van de Ven, F.H.M. Planning support system for climate adaptation: Composing effective sets of blue-green measures to reduce urban vulnerability to extreme weather events. Build. Environ. 2015, 83, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. From risk governance to city-citizen collaboration: Capitalizing on individual adaptation to climate change. Environ. Policy Gov. 2016, 26, 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, D. Environmental Governance: A Comparative Analysis of Nine City Case Studies. J. Int. Dev. 2001, 13, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schicklinski, J. Civil society actors as drivers of socio-ecological transition? In Green Spaces in European Cities as Laboratories of Social Innovation; WWWforEurope Working Papers Series No. 102; WWWforEurope: Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MINAMB. Le Infrastrutture Verdi e i Servizi Ecosistemici in Italia come Strumento per le Politiche Ambientali e la Green Economy: Potenzialità, Criticità e Proposte; Ministero dell’Ambiente: Roma, Italy, 2013.

- Mees, H.L.P.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Runhaar, H.A.C. Exploring the scope of public and private responsibilities for climate adaptation. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2012, 14, 305–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, E.L.; Eakin, H. Managing private and public adaptation to climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2012, 22, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, T. Panacea or paradox? Cross-sector partnerships, climate change, and development. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2010, 1, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasbergen, P. (Ed.) Co-Operative Environmental Governance, Environment & Policy; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos, M.C.; Agrawal, A. Environmental governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2006, 31, 297–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bason, C. Leading Public Sector Innovation: Co-Creating for a Better Society; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, D.R.; Plummer, R.; Berkes, F.; Arthur, R.I.; Charles, A.T.; Davidson-Hunt, I.J.; Diduck, A.P.; Doubleday, N.C.; Johnson, D.S.; Marschke, M.; et al. Adaptive co-management for social–ecological complexity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Quinn, T.; Lorenzoni, I.; Murphy, C.; Sweeney, J. Changing social contracts in climate-change adaptation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, A. The role of institutions in sustainable urban governance. Nat. Resour. Forum 2016, 40, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, J.; Plummer, R.; Haug, C.; Huitema, D. Learning effects of interactive decision-making processes for climate change adaptation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 27, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, E.; Wamsler, C. Collaborative Governance for Climate Change Adaptation: Mapping citizen–municipality interactions. Environ. Policy Gov. 2018, 28, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, N.; Shanahan, D.F.; Shumway, N.; Bekessy, S.A.; Fuller, R.A.; Watson, J.E.; Maggini, R.; Hole, D.G. Opportunities for biodiversity conservation as cities adapt to climate change. Geo Geogr. Environ. 2018, 5, e00052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miccoli, S.; Finucci, F.; Murro, R. Social evaluation approaches in landscape projects. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7906–7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.Y.; Jim, C.Y. Willingness of residents to pay and motives for conservation of urban green spaces in the compact city of Hong Kong. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Technical Information on Green Infrastructures (GI)—Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital; Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Naumann, S.; McKenna, D.; Kaphengst, T. Design, Implementation and Cost Elements of Green Infrastructure Projects; Final Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R. (Ed.) Ecological Economics: The Science and Management of Sustainability; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, K.; Elands, B.; Buijs, A. Social interactions in urban parks: Stimulating social cohesion? Urban For. Uran Green. 2010, 9, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worpole, K.; Knex, K. The Social Value of Public Spaces; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein, S.S. Cities and Diversity. Urban Aff. Rev. 2005, 41, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloutas, T.; Pantelidou, M. Debats and developments: The glass menagerie of urban governance and social cohesion concepts and stake/concepts as stakes. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COM. Comunicazione della Commissione al Parlamento Europeo, al Consiglio, al Comitato Economico e Sociale Europeo e al Comitato delle Regioni. Infrastrutture Verdi—Rafforzare il Capitale Naturale in Europa; 249 Final; COM: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gryseels, M. Relevance of the Concept of Ecosystem Services in the Practice of Brussels Environment (BE). Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, J.; Saarela, S.-R.; Tarja Söderman, T.; Kopperoinen, L.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.; Väre, S.; Kotze, D.J. Using the ecosystem services approach for betterplanning and conservation of urban green spaces: A Finland case study. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 3225–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, O.H.; Olafsson, A.S. Recreational mapping and planning for enlargement of the green structure in greater Copenhagen. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaland, C.; Konijnendijkvan den Bosch, C. Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: A review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, J.; Gausset, Q. Community Governance and Citizen-Driven Initiatives in Climate Change Mitigation; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.P.; Hole, D.G.; Zavaleta, E.S. Harnessing nature to help people adapt to climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Luederitz, C.; Ebba, Brink. Local levers for change: mainstreaming ecosystem-based adaptation into municipal planning to foster sustainability transitions. Global Environ. Chang. 2004, 29, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasny, M.E.; Russ, A.; Tidball, K.G.; Elmqvist, T. Civic ecology practices: Participatory approaches to generating and measuring ecosystem services in cities. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 7, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, V.T.; Scuderi, A.; Stella, G.; Sturiale, L.; Timpanaro, G.; Trovato, M.R. The integration of agriculture in the politics of social regeneration of degraded urban areas. In Integrated Evaluation for the Management of Contemporary Cities. Results of SIEV, Green Energy and Technology; Mondini, G., Fattinnanzi, E., Oppio, A., Bottero, M., Stanghellini, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sturiale, L.; Calabro’, F.; Della Spina, L. Cultural Planning: A Model of Governance of the Landscape and Cultural Resources in Development Strategies in Rural Contexts. In Utopias and Dystopias in Landscape and Cultural Mosaic—Visions Values Vulnerability; Rezekne Higher Education Institution: Rēzekne, Latvia, 2013; Volume V, pp. 177–188. ISSN 1691-5887. [Google Scholar]

- Sturiale, L.; Trovato, M.R. A Model for Generating Social Values and Decisions to Support the Planning of a SCI; LaborEst: Milan, Italy, 2015; Volume 10, ISSN 1691-5887. [Google Scholar]

- Ahiablame, L.; Engel, B.; Chaubey, I. Representation and evaluation of low impact development practices with L-THIA-LID: An example for planning. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderberg, H.; Karman, E. MIKA: Methodologies for Integration of Knowledge Areas—The Case of SustainableUrban Water Management; Department of Built Environment & Sustainable Development, Chalmers Architecture, Chalmers University of Technology: Goeteborg, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Panell, D.J.; Glenn, N.A. A framework for the economic evaluation and selection of sustainability indicators in agriculture. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 33, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, G. Social multicriteria evaluation of farming practices in the presence of soil degradation. A case study in Southern Tuscany, Italy. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2009, 11, 1107–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas Isaza, O.L. La evaluación multicriterio social y su aporte a la conservación de los bosques social multicriteria. Revista Facultad Nacional de Agronomía Medellín 2005, 58, 2665–2683. [Google Scholar]

- De Marchi, B.; Funtowicz, S.O.; Lo Cascio, S.; Munda, G. Combining participative and institutional approacheswith multicriteria evaluation. An empirical study for water issues in Troina, Sicily. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 34, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.; Matarazzo, B.; Slowinski, R. Dominance based Rough Set Approach to decision under uncertainty and time preference. Ann. Oper. Res. 2010, 176, 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaretto, S.; Siciliano, G.; Turvani, M. Integrating adaptive governance and participatory multicriteria methods: A framework for climate adaptation governance. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, A.; Sturiale, L. Multi-criteria evaluation model to face phytosanitary emergencies: The case of citrus fruits farming in Italy. Agric. Econ 2016, 62, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notaro, S.; De Salvo, M. Estimating the economic benefits of the landscape function of ornamental trees in a sub-Mediterranean area. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiman, T.; Gartner, J. Are residents willing to pay for their community forests? Results of a contingent valuation survey in Missouri, USA. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morancho, A.B. A hedonic valuation of urban green areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 66, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.C.; Carson, R.T. Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: The Contingent Valuation Method; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Luttik, J. The value of trees, water and open space as reflected by house prices in The Netherlands. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 48, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.M. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory and Methods, 2nd ed.; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, J.F.; McPherson, E.G.; Schroeder, H.W.; Rowntree, R.A. Assessing the benefits and costs of the urban forest. J. Arboricult. 1992, 18, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Munda, G. Social Multicriteria Evaluation for a Sustainable Economy; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Munda, G. A NAIADE based Approach for Sustainability Benchmarking. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2006, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmelev, E.S.; Rodriguez-Labajos, B. Dynamic multidimensional assessment of sustainability at the macro level: The case of Austria. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2560–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrieri, F.; Concilio, G.; Nijkamp, P. Decision support tools for urban contingency policy. A scenario approach to risk management of the Vesuvio area in Naples—Italy. J. Conting. Crisis Manag. 2002, 10, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.P. Choice and Preference of Water Supply Institutions—An Exploratory Study of Stakeholders’ Preferences of Water Sector Reform in Metro City of Delhi, India. 2007. Available online: http://agua.isf.es/semana%E2%80%A6/Doc7_APTiwari_2pag_xcra_a_dobre%20cara.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2017).

- Bekessy, S.A.; White, M.; Gordon, A.; Moilanen, A.; Mccarthy, M.A.; Wintle, B.A. Transparent planning for biodiversity and development in the urban fringe. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 108, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogd, H. Multiple Criteria Evaluation for Urban and Regional Planning; Lion: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Research. Benefits of Green Infrastructures; Report by Forest Research; Forest Research: Farnham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Langemeyerab, J.; Gómez-Baggethuncf, E.; Haasede, D.; Scheuerd, S.; Elmqvistb, T. Bridging the gap between ecosystem service assessments and land-use planning through Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA). Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srdjevic, Z.; Lakicevic, M.; Srdjevic, B. Approach of decision making based on the analytic hierarchy process for urban landscape management. Environ. Manag. 2013, 51, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grêt-Regamey, A.; Celio, E.; Klein, T.M.; Wissen Hayek, U. Understanding ESs trade-offs with interactive procedural modeling for sustainable urban planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanon, S.; Hein, T.; Douven, W.; Winkler, P. Quantifying. ES trade-offs: The case of an urban floodplain in Vienna, Austria. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 111, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).