The Impact of Earthquake on Poverty: Learning from the 12 May 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Wenchuan Earthquake Disaster Situation

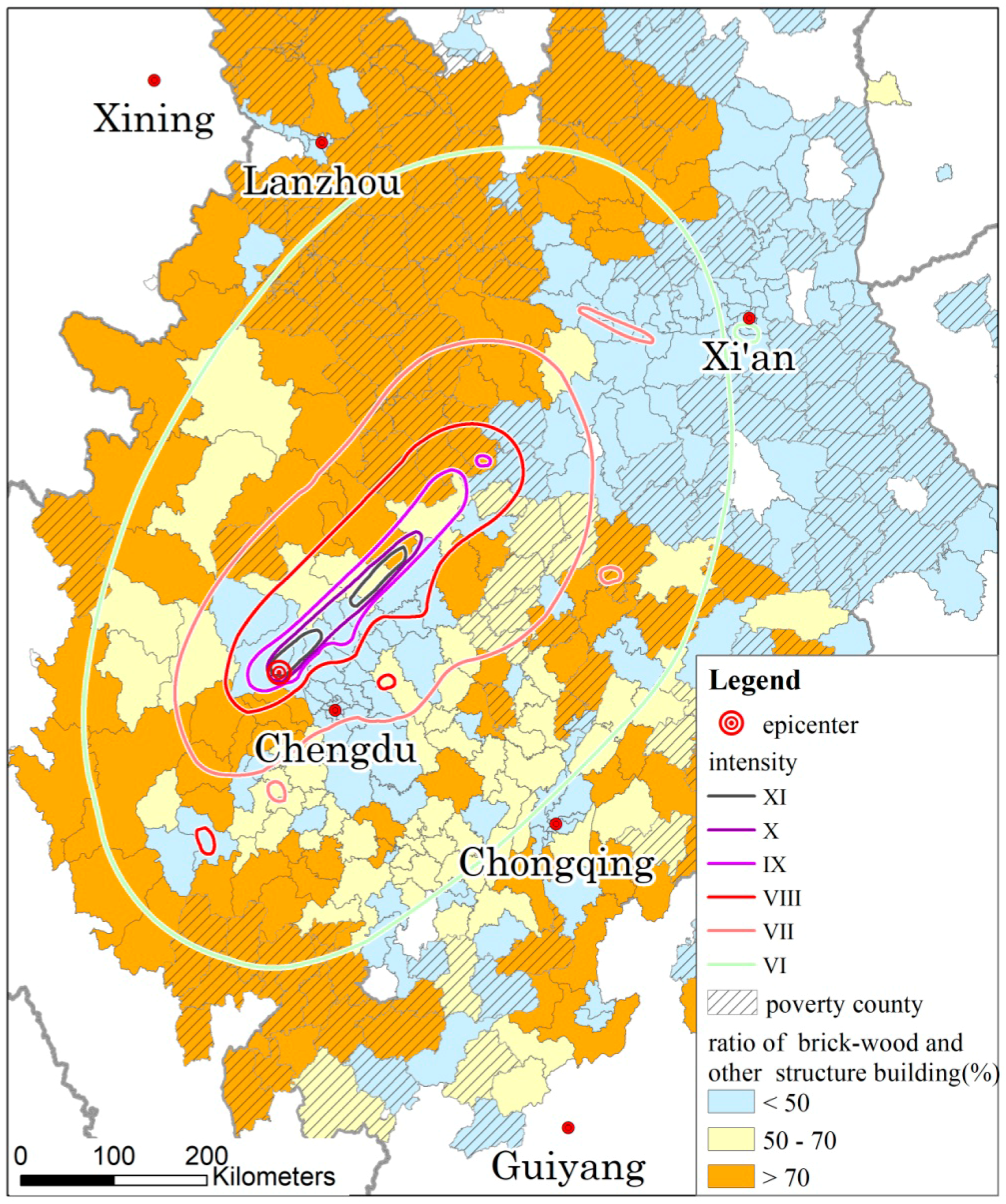

1.2. Basic Situation of the Wenchuan Earthquake-Stricken Area

1.3. Poverty Situation before the Earthquake

1.4. Poverty Situation after the Earthquake

2. The Impact of the Wenchuan Earthquake on Poverty

2.1. The Impact of Wenchuan Earthquake on Poverty-Stricken Counties

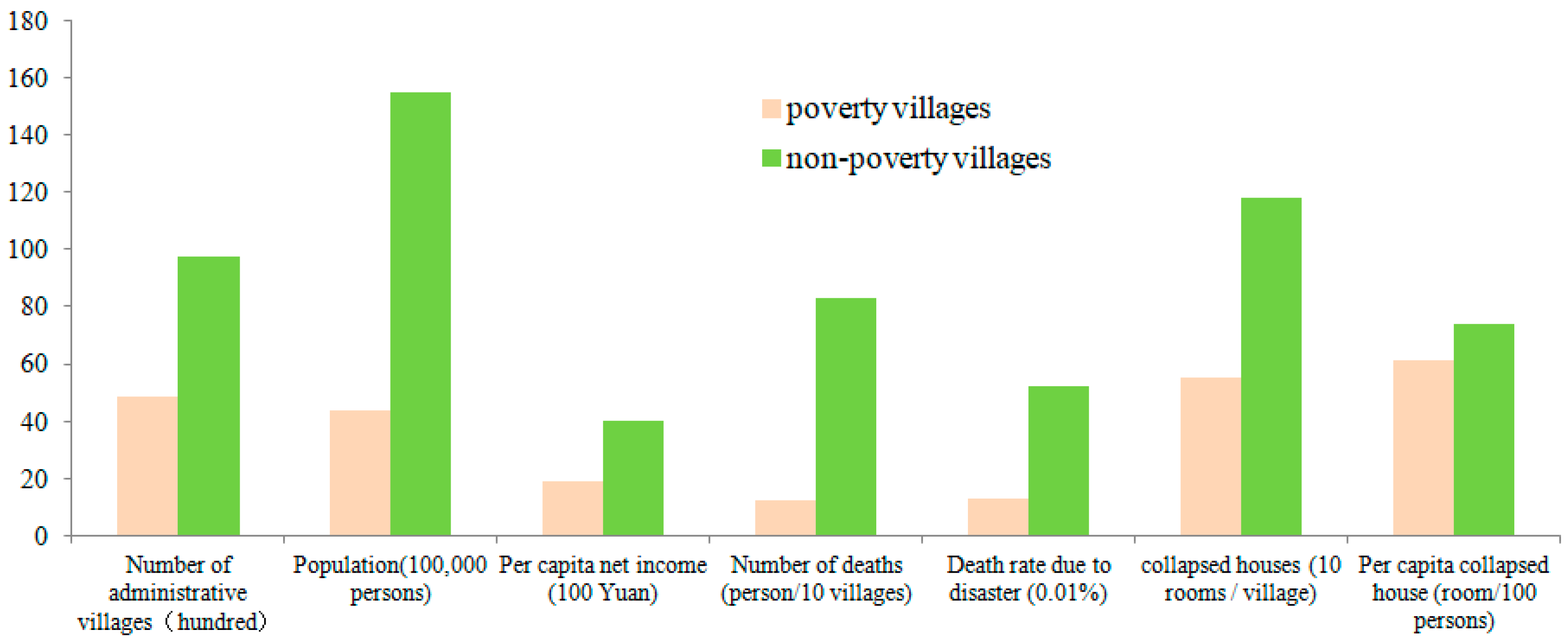

2.2. The Impact of the Wenchuan Earthquake on Poverty-Stricken Villages

2.3. The Impact of the Wenchuan Earthquake on Poverty-Stricken Households

2.3.1. The Impact of the Wenchuan Earthquake on the Population

2.3.2. The Impact of Earthquakes on Rural Housing

2.3.3. The Impact of Earthquakes on Farmers’ Incomes and Expenses

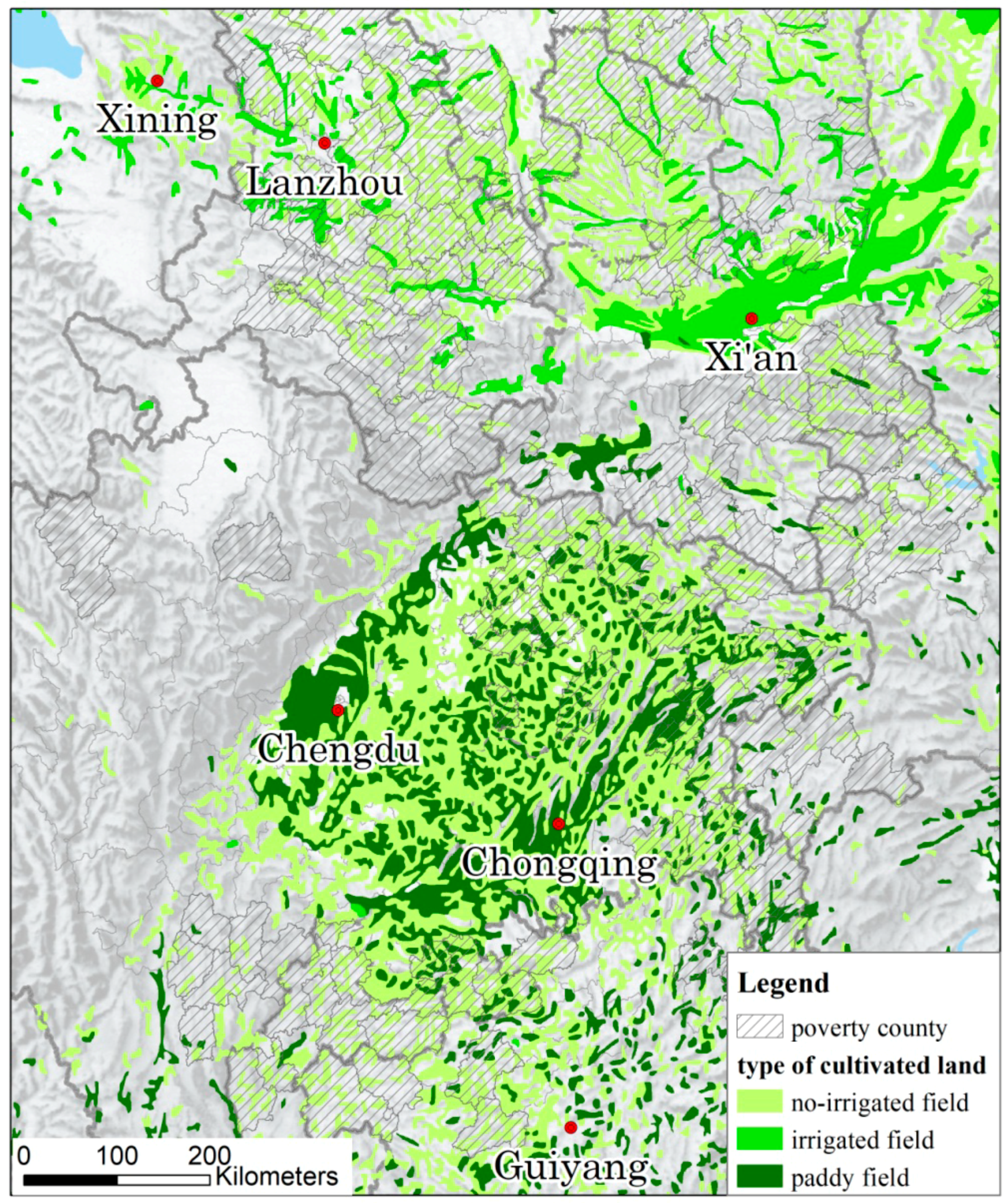

2.3.4. The Impact of the Wenchuan Earthquake on Farmers’ Cultivated Land

3. Reflections on the Model of Post-Disaster Reconstruction and Poverty Alleviation

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The impact of the earthquake on the population with different characteristics is different. For households with different incomes, the proportion of casualties of wealthy households due to disasters is lower than that of ordinary households and poor households; for different gender and age structures, women are more likely to have suffered from the disaster than men, and older people are more likely to have suffered from the disaster than young people.

- (2)

- In terms of the impact of the earthquake on housing collapse, the proportion of collapsed housing of poor households is greater than that of ordinary households and wealthy households. Among the proportion of housing needs to be repaired, the proportion of housing of wealthy households is the largest, and that of the poor households is the smallest.

- (3)

- As far as household incomes after the disaster are concerned, there has been an increase in the number of wealthy households, and that of medium and poor households have decreased significantly. The expenditures of wealthy households have increased after the disaster, while the ordinary households and poor households have shown a trend of shrinking.

- (4)

- The proportion of damaged cultivated land for ordinary households and wealthy households is larger than that for poor households. In terms of housing occupied farmland, poor households and ordinary households are larger than rich households.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dunford, M.; Li, L. Earthquake reconstruction in Wenchuan: Assessing the state overall plan and addressing the ‘forgotten phase’. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lu, Y. Meta-synthesis pattern of post-disaster recovery and reconstruction: Based on actual investigation on 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Nat. Hazards 2012, 60, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, X.K. Developing a new perspective to study the health of survivors of Sichuan earthquakes in China: A study on the effect of post-earthquake rescue policies on survivors’ health-related quality of life. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2013, 11, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Salazar, M.A.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, X. Social protection during disasters: Evidence from the Wenchuan earthquake. IDS Bull. 2010, 41, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Han, J.; Xiao, D.; Ma, C.; Chen, B. A report on the reproductive health of women after the massive 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2010, 108, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wang, L.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Shen, J. Mental health problems among children one-year after Sichuan earthquake in China: A follow-up study. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e14706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; He, G.; Ma, Y.; Deng, D.; Zhao, Y.; Ru, X. The living conditions and policy needs of residents in the earthquake affected areas. In Blue Book of China’s Society: Society of China Analysis and Forecast (2009); Social Sciences Academic Press (China): Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, X.; Liu, C.; Li, N. Social support and quality of life: A cross-sectional study on survivors eight months after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Chu, P.; Wang, X. Health-Related Quality of Life of Chinese Earthquake Survivors: A Case Study of Five Hard-Hit Disaster Counties in Sichuan. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 119, 943–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.P.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lin, J.; Shen, J.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, W. Emergency medical rescue efforts after a major earthquake: Lessons from the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Lancet 2012, 379, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.J.; Chen, B.F.; Ren, J.Z.; Chang, T.T. Natural Disaster’s Impact Evaluation of Rural Households’ Vulnerability: The case of Wenchuan earthquake. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2010, 1, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W. The Impact of Wenchuan Earthquake on Poverty and Its Enlightenment to Disaster Emergency Response System. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on “Reconstruction after Disaster and Poverty Alleviation”, Beijing, China, 28 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kun, P.; Chen, X.; Han, S.; Gong, X.; Chen, M.; Zhang, W.; Yao, L. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in Sichuan Province, China after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Public Health 2009, 123, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.H.; Liu, X.; Hu, X.; Qiu, C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Li, T. Risk indicators for post-traumatic stress disorder in adolescents exposed to the 5.12 Wenchuan earthquake in China. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 189, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirayama, Y. Collapse and reconstruction: Housing recovery policy in Kobe after the Hanshin Great Earthquake. Hous. Stud. 2000, 15, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchester, P. Cyclone mitigation, resource allocation and post-disaster reconstruction in south India: Lessons from two decades of research. Disasters 2000, 24, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, Y.; Inui, T.; Hosoi, T.; Takabe, I.; Kawakami, A. The impact of the Great East Japan earthquake on the labor market: Need to resolve the employment mismatch in the disaster-stricken areas. Jpn. Labor Rev. 2012, 9, 4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Cao, R.X. Employment assistance policies of Chinese government play positive roles! The impact of post-earthquake employment assistance policies on the health-related quality of life of Chinese earthquake populations. Soc. Indic Res. 2015, 120, 835–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yuan, P.; Jia, H.; Li, A.L.; Liu, X.X.; Ye, Y.L. Time trend of post-traumatic stress disorder among middle school students after Wenchuan earthquake. Chin. J. Public Health 2011, 27, 303–304. [Google Scholar]

- Genda, Y. Future employment policy suggested by the post-earthquake response. Jpn. Labor Rev. 2012, 9, 86–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.Y. Lessons learned from the “5.12” Wenchuan Earthquake: Evaluation of earthquake performance objectives and the importance of seismic conceptual design principles. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2008, 7, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. A preliminary report on the Great Wenchuan earthquake. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2008, 7, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisabeth, K.; Ana, M.C.; Bastien, A. The impact of the 12 May 2008 Wenchuan earthquake on industrial facilities. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2010, 23, 242–248. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, F.; Chakravarty, S. The measurement of multidimensional poverty. J. Econ. Inequal. 2003, 1, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ravallion, M. Data in transition: Assessing rural living standards in Southern China. China Econ. Rev. 1996, 7, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Li, Y.H.; Chi, G.B.; Xiao, S.Y.; Ozanne-Smith, J.; Stevenson, M.; Phillips, M.R. Injury-related fatalities in China: An under-recognised public-health problem. Lancet 2008, 372, 1765–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maly, E.; Shiozaki, Y. Towards a policy that supports people-centered housing recovery—Learning from housing reconstruction after the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in Kobe, Japan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2012, 3, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhua Net. Sichuan Approved 15 Counties Such as Beichuan to Exit the Poverty Counties. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/2018-08/01/c_1123207183.htm (accessed on 1 August 2018).

| Datasets | Sources |

|---|---|

| Earthquake epicenter and Seismic Intensity Scale | China Earthquake Administration |

| Earthquake intensity | National Disaster Reduction Center of the Ministry of Civil Affairs |

| Earthquake disaster data | National Disaster Reduction Center of the Ministry of Civil Affairs |

| Distribution of poverty counties | Aid-the-Poor Development Office of the State Council |

| Socioeconomic statistics of earthquake-stricken areas | National Bureau of Statistics |

| County population data | National Bureau of Statistics |

| Housing structural data | The sixth national census of National Bureau of Statistics |

| Cultivated land type data | Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, H.; Chen, F.; Pan, D.; Zhang, C. The Impact of Earthquake on Poverty: Learning from the 12 May 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124704

Jia H, Chen F, Pan D, Zhang C. The Impact of Earthquake on Poverty: Learning from the 12 May 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. Sustainability. 2018; 10(12):4704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124704

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Huicong, Fang Chen, Donghua Pan, and Chuanrong Zhang. 2018. "The Impact of Earthquake on Poverty: Learning from the 12 May 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake" Sustainability 10, no. 12: 4704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124704

APA StyleJia, H., Chen, F., Pan, D., & Zhang, C. (2018). The Impact of Earthquake on Poverty: Learning from the 12 May 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. Sustainability, 10(12), 4704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124704