Sustainable Global Sourcing: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What is the knowledge structure of existing studies in the field of SGS?

- Under the present research structure in this field, could we find some insightful implications for the future research agenda for SGS?

2. Methodology and Primary Data Statistics

2.1. Defining the Appropriate Keywords

2.2. Search Results

2.3. Initial Data Statistics

3. Citation and Co-Citation Analysis

3.1. Citation Analysis

3.2. PageRank Analysis

3.3. The Analysis of Co-Citation

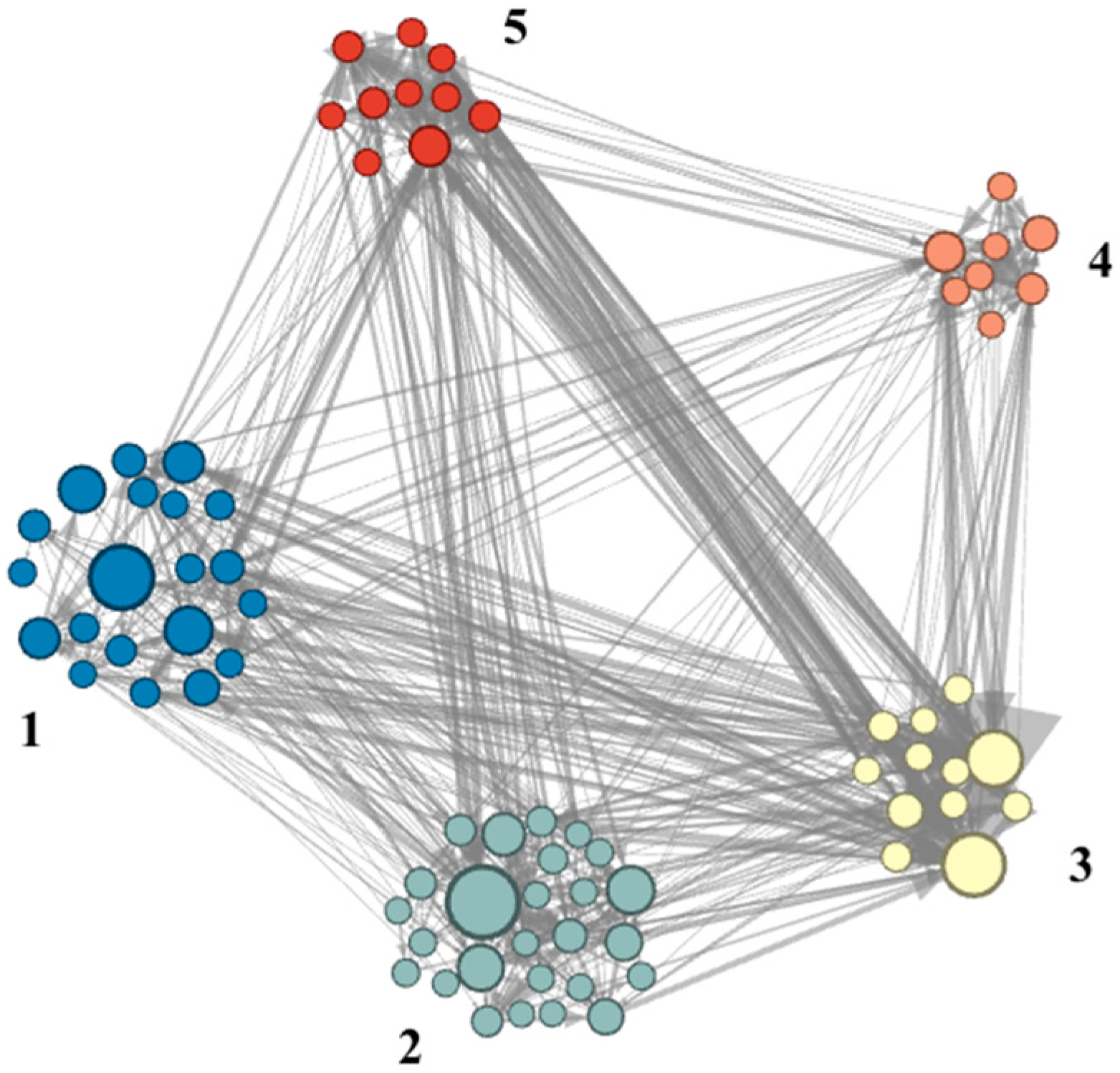

3.3.1. Data Clustering: Research Themes in the Literature

3.3.2. Analysis of the Primary Research Clusters Based on Local Co-Citation

4. Content Analysis of Five Clusters

4.1. Cluster 1: GS Practices and Environmental Performance

4.2. Cluster 2: Social Sustainability/Ethical Sourcing Practice

4.3. Cluster 3: Sustainability Certification Adoption and Auditing

4.4. Cluster 4: Modeling Method for Green Supplier Selection of GS

4.5. Cluster 5: Interrelationship of Three Aspects of Sustainability

4.6. Methodologies, Theories, Industry Sectors and Disciplines for the Reviewed Articles

5. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Contractor, F.J.; Kumar, V.; Kundu, S.K.; Pedersen, T. Reconceptualizing the firm in a world of outsourcing and offshoring: The organisational and geographical relocation of high-value company functions. J. Manag. Stud. 2000, 47, 1417–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenherr, T.; Modi, S.B.; Benton, W.C.; Carter, C.R.; Choi, T.Y.; Larson, P.D.; Wagner, S.M. Research opportunities in purchasing and supply management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 4556–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javalgi, R.R.G.; Dixit, A.; Scherer, R.F. Outsourcing to emerging markets: Theoretical perspectives and policy implications. J. Int. Manag. 2009, 15, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Mena, C.; Khan, O.; Yurt, O. Approaches to managing global sourcing risk. Supply Chain Manag. 2011, 16, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurro, C.; Russo, A.; Perrini, F. Shaping sustainable value chains: Network determinants of supply chain governance models. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Sustainable fashion supply chain: Lessons from H&M. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6236–6249. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, F.; Ramasar, V.; Nicholas, K.A. Problems with Firm-Led Voluntary Sustainability Schemes: The Case of Direct Trade Coffee. Sustainability 2017, 9, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassini, E.; Surti, C.; Searcy, C. A literature review and a case study of sustainable supply chains with a focus on metrics. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, M.K.; Roehrich, J.; Eßig, M.; Harland, C. Driving sustainable supply chain management in the public sector: The importance of public procurement in the European Union. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 19, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrich, J.K.; Hoejmose, S.U.; Overland, V. Driving green supply chain management performance through supplier selection and value internalisation: A self-determination theory perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoejmose, S.U.; Roehrich, J.K.; Grosvold, J. Is doing more doing better? The relationship between responsible supply chain management and corporate reputation. Ind. Market. Manag. 2014, 43, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosvold, J.; Hoejmose, S.U.; Roehrich, J.K. Squaring the circle: Management, measurement and performance of sustainability in supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 19, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.R.; Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Special topic forum on sustainable supply chain management: Introduction and reflections on the role of purchasing management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 45, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintens, L.; Pauwels, P.; Matthyssens, P. Global Purchasing: State of the Art and Research Directions. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2006, 12, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monczka, R.M.; Trent, R.J. Global Sourcing: A Development Approach. Int. J. Purch. Mater. Manag. 1991, 27, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birou, L.M.; Fawcett, S.E. International purchasing: Benefits, requirements, and challenges. Int. J. Purch. Mater. Manag. 1993, 29, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozarth, C.; Handfield, R.; Das, A. Stages of global sourcing strategy evolution: An exploratory study. J. Oper. Manag. 1998, 16, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, R.J.; Monczka, R.M. Understanding integrated global sourcing. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2003, 33, 607–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frear, C.R.; Metcalf, L.E.; Alguire, M.S. Offshore sourcing: its nature and scope. J. Supply Chain Manag. 1992, 28, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambos, B.; Schlegelmilch, B.B. Innovation and control in the multinational firm: A comparison of political and contingency approaches. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R. Purchasing social responsibility and firm performance: The key mediating roles of organisational learning and supplier performance. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2005, 35, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.; Lewis, M.; Miemczyk, J.; Brandon-Jones, A. Implementing supply practice at Bridgend engine plant: The influence of institutional and strategic choice perspectives. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2007, 27, 754–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reuter, C.; Foerstl, K.A.I.; Hartmann, E.V.I.; Blome, C. Sustainable global supplier management: The role of dynamic capabilities in achieving competitive advantage. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2010, 46, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund-Thomsen, P. The global sourcing and codes of conduct debate: Five myths and five recommendations. Dev. Chang. 2008, 39, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, L.M.; Federico, S.; Klass, P.; Abrams, M.A.; Dreyer, B. Literacy and child health: A systematic review. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009, 163, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodaverdi, R.; Jafarian, A. A fuzzy multi criteria approach for measuring sustainability performance of a supplier based on triple bottom line approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 345–354. [Google Scholar]

- Gualandris, J.; Klassen, R.D.; Vachon, S.; Kalchschmidt, M. Sustainable evaluation and verification in supply chains: Aligning and leveraging accountability to stakeholders. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. How to appraise the studies: An introduction to assessing study quality. In Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; Blackwell publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 125–163. [Google Scholar]

- Fahimnia, B.; Sarkis, J.; Davarzani, H. Green supply chain management: A review and bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 162, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahi, P.; Searcy, C. A comparative literature analysis of definitions for green and sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BibExcel Homepage. Available online: http://homepage.univie.ac.at/juan.gorraiz/bibexcel/ (accessed on 6 November 2016).

- Gelphi Homepage. Available online: https://gephi.org (accessed on 8 December 2016).

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In Proceedings of the Third International ICWSM Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 17–20 May 2009; Adar, E., Hurst, M., Finin, T., Glance, N.S., Nicolov, N., Tseng, B.L., Eds.; The AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Cronin, B. Popular and/or prestigious? Measures of scholarly esteem. Inf. Process. Manag. 2011, 47, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handfield, R.; Walton, S.V.; Sroufe, R.; Melnyk, S.A. Applying environmental criteria to supplier assessment: A study in the application of the Analytical Hierarchy Process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2002, 141, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P. Greening the supply chain: A new initiative in South East Asia. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 632–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Holt, D. Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic performance? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noci, G. Designing ‘green’ vendor rating systems for the assessment of a supplier’s environmental performance. Eur. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 1997, 3, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Jennings, M.M. Social responsibility and supply chain relationships. Transp. Res. E-Log. 2002, 38, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Carter, J.R. Interorganisational determinants of environmental purchasing: Initial evidence from the consumer products industries. Decis. Sci. 1998, 29, 659–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welford, R.; Frost, S. Corporate social responsibility in Asian supply chains. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koplin, J.; Seuring, S.; Mesterharm, M. Incorporating sustainability into supply management in the automotive industry—The case of the Volkswagen AG. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffen, C.A.; Rothenberg, S. Suppliers and environmental innovation: the automotive paint process. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2000, 20, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsidisin, G.A.; Siferd, S.P. Environmental purchasing: A framework for theory development. Eur. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2001, 7, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.F.; Power, D.J. Use the supply relationship to develop lean and green suppliers. Supply Chain Manag. 2005, 10, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Impacts of corporate code of conduct on labor standards: A case study of Reebok’s athletic footwear supplier factory in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsidisin, G.A.; Hendrick, T.E. Purchasing’s involvement in environmental issues: A multi-country perspective. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 1998, 98, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, S.; Gibbon, P. Quality standards, conventions and the governance of global value chains. Econ. Soc. 2005, 34, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.; Power, D.; Samson, D. Greening the automotive supply chain: A relationship perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2007, 27, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, S.; Motwani, R.; Page, L.; Winograd, T. What can you do with a web in your pocket? IEEE Data Eng. Bull. 1998, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P.N.; Panda, K.C.; Goswami, N.G. Citation analysis and research impact of National Metallurgical Laboratory, India during 1972–2007: A case study. Malays. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 15, 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hjørland, B. Theories of knowledge organisation—Theories of knowledge. In Proceedings of the 13th Meeting of the German ISKO, Potsdam, Germany, 19–20 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Radicchi, F.; Castellano, C.; Cecconi, F.; Loreto, V.; Parisi, D. Defining and identifying communities in networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 2658–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clauset, A.; Newman, M.E.; Moore, C. Finding community structure in very large networks. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 70, 066111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leydesdorff, L. Bibliometrics/citation networks. In The Encyclopedia of Social Networks; Barnett, G.A., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2011; pp. 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- Theyel, G. Customer and supplier relations for environmental performance. In Greening the Supply Chain; Springer: London, UK, 2006; pp. 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wycherley, I. Greening supply chains: The case of the Body Shop International. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 1999, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, P.R.; Singhal, K.; Wassenhove, L.N. Sustainable operations management. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2005, 14, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Wu, Z.; Wasserman, M.E. Thinking differently about purchasing portfolios: An assessment of sustainable sourcing. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2010, 46, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, S. Green supply chain practices and the selection of environmental technologies. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2007, 45, 4357–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullman, M.E.; Maloni, M.J.; Carter, C.R. Food for thought: Social versus environmental sustainability practices and performance outcomes. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 45, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R.; Andersen, M. Safeguarding corporate social responsibility (CSR) in global supply chains: How codes of conduct are managed in buyer-supplier relationships. J. Public Aff. 2006, 6, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, L. Ethical sourcing codes of large UK-based corporations: Prevalence, content, limitations. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Hillebrand, B.; McAlister, D. Managing socially-responsible buying: How to integrate non-economic criteria into the purchasing process. Eur. Manag. J. 2002, 20, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B. The effects of interorganisational governance on supplier’s compliance with SCC: An empirical examination of compliant and non-compliant suppliers. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 27, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Stoel, L. A model of socially responsible buying/sourcing decision-making processes. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2005, 33, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Galle, W.P. Green purchasing practices of US firms. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 1222–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P. The greening of suppliers—In the South East Asian context. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumwright, M.E. Socially responsible organisational buying: Environmental concern as a noneconomic buying criterion. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocka, D. Environmental supply chain management, ISO 14001 and RoHS. How are small companies in the electronics sector managing? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.; Morton, B.; New, S. Purchasing and environmental management: Interactions, policies and opportunities. Bus. Strategy Environ. 1996, 5, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogg, B. Greening a cotton-textile supply chain: A case study of the transition towards organic production without a powerful focal company. Green. Manag. Int. 2003, 43, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, M.K.; Shih, L.H. An empirical study of the implementation of green supply chain management practices in the electrical and electronic industry and their relation to organisational performances. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 4, 383–394. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, W.C.; Chuang, M.C. Using multi-objective genetic algorithm for partner selection in green supply chain problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 4244–4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.H.; Kang, H.Y.; Hsu, C.F.; Hung, H.C. A green supplier selection model for high-tech industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 7917–7927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, D.; Khodaverdi, R.; Olfat, L.; Jafarian, A.; Diabat, A. Integrated fuzzy multi criteria decision making method and multi-objective programming approach for supplier selection and order allocation in a green supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, M.H. Managing the environmental performance of production facilities in the electronics industry: More than application of the concept of cleaner production. J. Clean. Prod. 2003, 11, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A.; Chauhan, S.S.; Goyal, S.K. A fuzzy multicriteria approach for evaluating environmental performance of suppliers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 126, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberti, F.; Pontrandolfo, P.; Scozzi, B. Investigating corporate social responsibility in supply chains: A SME perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1579–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R. Purchasing and social responsibility: A replication and extension. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2004, 40, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Kale, R.; Grimm, C.M. Environmental purchasing and firm performance: An empirical investigation. Transp. Res. E-Log. 2000, 36, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R. Ethical issues in international buyer–supplier relationships: A dyadic examination. J. Oper. Manag. 2000, 18, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaysheh, A.; Klassen, R.D. The impact of supply chain structure on the use of supplier socially responsible practices. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2010, 30, 1246–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, S.; Smith, S. Do workers benefit from ethical trade? Assessing codes of labour practice in global production systems. Third World Q. 2007, 28, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.; Skjoett-Larsen, T. Corporate social responsibility in global supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 14, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bals, L.; Tate, W. Implementing Triple Bottom Line Sustainability into Global Supply Chains, 1st ed.; Greenleaf Publishing: Austin, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Luzzini, D.; Brandon-Jones, E.; Brandon-Jones, A.; Spina, G. From sustainability commitment to performance: The role of intra-and inter-firm collaborative capabilities in the upstream supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 165, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Formentini, M.; Taticchi, P. Corporate sustainability approaches and governance mechanisms in sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1920–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cruz, L.B.; Boehe, D.M. CSR in the global marketplace: Towards sustainable global value chains. Manag. Decis. 2008, 46, 1187–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.F.; Hu, P.J.H.; Wei, C.P.; Huang, J.W. Green Purchasing by MNC Subsidiaries: The Role of Local Tailoring in the Presence of Institutional Duality. Decis. Sci. 2014, 45, 647–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M. Environmental Sustainability in the Fashion Supply Chain in India. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 7, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, S. International operations and Sustain. Dev.: Should national culture matter? Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Klassen, R.D. Drivers and enablers that foster environmental management capabilities in small- and medium-sized suppliers in supply chains. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2008, 17, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, I.; Humby, S. Embedding corporate responsibility into supply: A snapshot of progress. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Kielkiewicz-Young, A. Sustainable supply network management. Corp. Environ. Strategy 2001, 8, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerstl, K.; Reuter, C.; Hartmann, E.; Blome, C. Managing supplier sustainability risks in a dynamically changing environment—Sustainable supplier management in the chemical industry. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2010, 16, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, R.; Abdullah, R.; Hassan, M.G.; Sobry, S.C. Environmental Sustainability Performance: The Influence of Supplier and Customer Integration. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 2673–2678. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, L.M.; Campos, L.M.; Vazquez-Brust, D.A.; Vazquez-Brust, D.A. Lean and green synergies in supply chain management. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 21, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Xue, L.; Sun, C.; Zhang, C. Product transportation distance-based supplier selection in sustainable supply chain network. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotabe, M.; Murray, J.Y. Global sourcing strategy and sustainable competitive advantage. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.U.; Arjoon, S. Through Thick and Thin? How Self-determination Drives the Corporate Sustainability Initiatives of Multinational Subsidiaries. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, S.; Mao, Z. Linking supply chain strength to Sustain. Dev.: A country-level analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1552–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, C.; Sierra, V.; Rodon, J. Sustainable operations: Their impact on the triple bottom line. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandris, J.; Golini, R.; Kalchschmidt, M. Do supply management and global sourcing matter for firm sustainability performance? An international study. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 19, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, E.; Macchi, C.; Fiaschi, D. The social irresponsibility of international business: A novel conceptualization. In International Business and Sustainable Development; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; pp. 141–171. [Google Scholar]

- Egels-Zandén, N. Revisiting supplier compliance with MNC codes of conduct: Recoupling policy and practice at Chinese toy suppliers. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 119, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffis, S.E.; Autry, C.W.; Thornton, L.M.; Brik, A.B. Assessing antecedents of socially responsible supplier selection in three global supply chain contexts. Decis. Sci. 2014, 45, 1187–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.F. Leveraging Reputational Risk: Sustainable Sourcing Campaigns for Improving Labour Standards in Production Networks. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancha, C.; Longoni, A.; Giménez, C. Sustainable supplier development practices: Drivers and enablers in a global context. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2015, 21, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.M. Improving social responsibility in RMG industries through a new governance approach in laws. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Toppinen, A.; Lantta, M. Managerial Perceptions of SMEs in the Wood Industry Supply Chain on Corporate Responsibility and Competitive Advantage: Evidence from China and Finland. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisul Huq, F.; Stevenson, M.; Zorzini, M. Social sustainability in developing country suppliers: An exploratory study in the ready made garments industry of Bangladesh. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 610–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, S.J. Globalization, athletic footwear commodity chains and employment relations in China. Organ. Stud. 2001, 22, 531–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tulder, R.; Kolk, A. Multinationality and corporate ethics: Codes of conduct in the sporting goods industry. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2001, 32, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, C.A.; Maclagan, P.W. Managers’ personal values as drivers of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 50, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaeshi, K.M.; Osuji, O.K.; Nnodim, P. Corporate social responsibility in supply chains of global brands: A boundaryless responsibility? Clarifications, exceptions and implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laudal, T. An attempt to determine the CSR potential of the international clothing business. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egels-Zandén, N. Suppliers’ compliance with MNCs’ codes of conduct: Behind the scenes at Chinese toy suppliers. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A. Corporate strategy and the management of ethical trade: The case of the UK food and clothing retailers. Environ. Plan. A 2005, 37, 1145–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.; Seuring, S.; Beske, P. Sustainable supply chain management and inter-organisational resources: A literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 230–245. [Google Scholar]

- Airike, P.E.; Rotter, J.P.; Mark-Herbert, C. Corporate motives for multi-stakeholder collaboration–corporate social responsibility in the electronics supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damron, T.; Melton, A.; Smith, A.D. Collaborative and ethical consideration in the vendor selection process. Int. J. Process Manag. Benchmark. 2016, 6, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.E.; Spekman, R.E.; Kamauff, J.W.; Werhane, P. Corporate social responsibility in global supply chains: A procedural justice perspective. Long Range Plan. 2007, 40, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.D.; Vereecke, A. Social issues in supply chains: Capabilities link responsibility, risk (opportunity), and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, R.; Amengual, M.; Mangla, A. Virtue out of necessity? Compliance, commitment, and the improvement of labor conditions in global supply chains. Politics Soc. 2009, 37, 319–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Garavito, C.A. Global governance and labor rights: Codes of conduct and anti-sweatshop struggles in global apparel factories in Mexico and Guatemala. Politics Soc. 2005, 33, 203–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaghey, J.; Reinecke, J.; Niforou, C.; Lawson, B. From employment relations to consumption relations: Balancing labor governance in global supply chains. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 53, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egels-Zandén, N. Not made in China: Integration of social sustainability into strategy at Nudie Jeans Co. Scand. J. Manag. 2016, 32, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, B.J.; Amoding, F.; Krishnan, A. Social and Economic Upgrading in Floriculture Global Value Chains: Flowers and Cuttings GVCs in Uganda, June 2014. Capturing the Games Working Pater 42. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2456600 (accessed on 21 February 2018).

- Lee, J.; Gereffi, G. Global value chains, rising power firms and economic and social upgrading. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2015, 11, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Jolley, G.J.; Handfield, R. Environmental management systems and green supply chain management: Complements for sustainability? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distelhorst, G.; Locke, R.M.; Pal, T.; Samel, H. Production goes global, compliance stays local: Private regulation in the global electronics industry. Regul. Gov. 2015, 9, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prado, A.M.; Woodside, A.G. Deepening understanding of certification adoption and non-adoption of international-supplier ethical standards. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, C.J. Global diffusion of ISO 9000 certification through supply chains. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2006, 8, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.B. Responsible sourcing of metals: Certification approaches for conflict minerals and conflict-free metals. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helin, S.; Babri, M. Travelling with a code of ethics: a contextual study of a Swedish MNC auditing a Chinese supplier. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egels-Zandén, N.; Lindholm, H. Do codes of conduct improve worker rights in supply chains? A study of Fair Wear Foundation. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posthuma, A.; Bignami, R. ‘Bridging the Gap’? Public and Private Regulation of Labour Standards in Apparel Value Chains in Brazil. Compet. Chang. 2014, 18, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund-Thomsen, P.; Lindgreen, A. Corporate social responsibility in global value chains: Where are we now and where are we going? J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Sivakumar, R. Green supplier selection and order allocation in a low-carbon paper industry: Integrated multi-criteria heterogeneous decision-making and multi-objective linear programming approaches. Ann. Oper. Res. 2016, 238, 243–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ge, B.; Jiang, J.; Chen, Y. An integrated technology pushing and requirement pulling model for weapon system portfolio selection in defence acquisition and manufacturing. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. B-J. Eng. 2015, 229, 1046–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriolo, A.; Battini, D.; Persona, A.; Sgarbossa, F. Haulage sharing approach to achieve sustainability in material purchasing: New method and numerical applications. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 164, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, T.; Pang, C. Green supply chain coordination with greenhouse gases emissions management: a game-theoretic approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2004–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, A.C.; Sarkis, J. Identifying Robust portfolios of suppliers: A sustainability selection and development perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2088–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemechu, E.D.; Helbig, C.; Sonnemann, G.; Thorenz, A.; Tuma, A. Import-based Indicator for the Geopolitical Supply Risk of Raw Materials in Life Cycle Sustainability Assessments. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 20, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J.; Nispeling, T.; Sarkis, J.; Tavasszy, L. A supplier selection life cycle approach integrating traditional and environmental criteria using the best worst method. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Chavez, R.; Feng, M.; Wiengarten, F. Integrated green supply chain management and operational performance. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 19, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.R.; Chien, K.M.; Yang, T.N. Green component procurement collaboration for improving supply chain management in the high technology industries: A case study from the systems perspective. Sustainability 2016, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, H.; Sundarakani, B.; Vel, P. The impact of implementing green supply chain management practices on corporate performance. Compet. Rev. 2016, 26, 216–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y. Responsible supply chain management in the Asian context: the effects on relationship commitment and supplier performance. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2016, 22, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayet, L.; Vermeulen, W.J. Supporting smallholders to access sustainable supply chains: Lessons from the Indian cotton supply chain. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.R.; Scannell, T.V.; Calantone, R.J. A structural analysis of the effectiveness of buying firms’ strategies to improve supplier performance. Decis. Sci. 2000, 31, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, M.; Lim, J.S.; Vonderembse, M.A. The impact of supply-chain management capabilities on business performance. Supply Chain Manag. 2005, 10, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiengarten, F.; Longoni, A. A nuanced view on supply chain integration: A coordinative and collaborative approach to operational and sustainability performance improvement. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 20, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabhilkar, M.; Bengtsson, L.; Lakemond, N. Sustainable supply management as a purchasing capability: A power and dependence perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 36, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blowfield, M. CSR and Development: Is business appropriating global justice? Development 2004, 47, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, D.M.; Fernandes, M.F. The social desirability response bias in ethics research. J. Bus. Ethics 1991, 10, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbe, W.J.; Paulhus, D.L. Socially desirable responding in organisational behavior: A reconception. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 250–264. [Google Scholar]

- Ellram, L.M.; Tate, W.L. The use of secondary data in purchasing and supply management (P/SM) research. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2016, 22, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, L.; Pirttilä, M.; Viskari, S.; Schupp, F.; Kärri, T. Working capital management in the automotive industry: Financial value chain analysis. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2012, 18, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Transport. Transport Statistics Great Britain. Department for Transport, UK. Available online: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/transport-statistics-great-britain-2016 (accessed on 19 June 2017).

- McKinnon, A.C. The potential of economic incentives to reduce CO2 emissions from goods transport. In Proceedings of the 1st International Transport Forum on ‘Transport and Energy: The Challenge of Climate Change, Leipzig, Germany, 28–30 May 2008; OECD: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista, P. Environmental sustainability practices in the transport and logistics service industry: An exploratory case study investigation. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 12, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics and Geography. Child Labour Module 2011: National Survey of Occupation and Employment, Mexico Government Paper. Available online: www.beta.inegi.org.mx/proyectos/enchogares/modulos/mti/2011/ (accessed on 19 June 2017).

- Kim, S.; Colicchia, C.; Menachof, D. Ethical sourcing: An analysis of the literature and implications for future research. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.; Voss, C.A. Contingency research in operations management practices. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D. H-P executives face bribery inquiries. Wall Street J. 2010, B1. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304628704575186151115576646 (accessed on 19 June 2017).

- Bregman, R.; Peng, D.X.; Chin, W. The effect of controversial global sourcing practices on the ethical judgments and intentions of US consumers. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 36, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M.M.; Blome, C.; Bhakoo, V.; Paulraj, A. Sustainability in multi-tier supply chains: Understanding the double agency role of the first-tier supplier. J. Oper. Manag. 2016, 41, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Shevchenko, A. Why research in sustainable supply chain management should have no future. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 50, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.A.; Giménez Thomsen, C.; Arenas, D.; Pagell, M. NGOs’ Initiatives to Enhance Social Sustainability in the Supply Chain: Poverty Alleviation through Supplier Development Programs. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 52, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ployhart, R.E.; Vandenberg, R.J. Longitudinal research: The theory, design, and analysis of change. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 94–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, J.; Jia, F.; Gong, Y.; Brown, S. The role of supply chain leadership in the learning of sustainable practice: toward an integrated framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1458–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaufmann, L.; Carter, C.R. International supply relationships and non-financial performance—A comparison of US and German practices. J. Oper. Manag. 2006, 24, 653–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, S.I.; Lee, Y.H.; Memon, M.S. Sustainable and resilient supply chain network design under disruption risks. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6666–6686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Global Sourcing (GS) Keywords: |

| (global sourcing) OR (global purchas*) OR (global procur*) OR (global buying) OR (international sourcing) OR (international purchas*) OR (international procur*) OR (international buying) OR (worldwide sourcing) OR (worldwide purchas*) OR (worldwide procur*) OR (worldwide buying) OR foreign sourcing) OR (foreign purchas*) OR (foreign procur*) OR (foreign buying) OR (offshoring sourcing) OR (offshoring purchasin) OR (offshoring procurement) OR (offshoring buying) OR (import sourcing) OR (multinational sourcing) OR (global supplier) OR (international supplier) OR (multinational supplier) OR (multinational sourcing) OR (multinational procur*) OR (multinational purchas*) |

| AND |

| Green-Related Keywords: |

| Sustainab* OR environment* OR ecolog* OR green OR EMAS OR ISO14001 OR corporate social responsibility OR LEED OR (closed loop) OR recycl* OR (low carbon) |

| Social-Related Keywords: |

| (social accountability) OR social OR (social responsibility) OR CSR 1 OR ethic* OR SA8000 OR ISO26000 |

| Source | Publish Year | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Total | |

| Journal of Cleaner Production (JCP) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 29 | |||||||||||||

| Journal of Business Ethics (JBE) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 31 | |||||||||

| Supply Chain Management: An International Journal (SCMIJ) | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 13 | |||||||||||||||

| International Journal of Operations and Production Management (IJOPM) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 | |||||||||||

| Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management (CSREM) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 11 | ||||||||||||||

| Business Strategy and the Environment (BSE) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| International Journal of Production Economics (IJPE) | 1 | 6 | 3 | 10 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management (JPSM) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||

| International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management (IJPDLM) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Journal of Supply Chain Management (JSCM) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 13 | 11 | 16 | 6 | 13 | 18 | 5 | 13 | 11 | 1 | 131 |

| Author (Year) | Local Citation 1 | Global Citation 2 | |

| Rao (2002) [38] | 34 | 294 | |

| Rao and Holt (2005) [39] | 30 | 616 | |

| Noci (1997) [40] | 22 | 185 | |

| Carter and Jennings (2002) [41] | 20 | 144 | |

| Carter (2005) [22] | 20 | 129 | |

| Carter and Carter (1998) [42] | 19 | 177 | |

| Handfield et al. (2002) [37] | 18 | 396 | |

| Welford and Frost (2006) [43] | 18 | 101 | |

| Koplin et al. (2007) [44] | 17 | 142 | |

| Geffen and Rothenberg (2000) [45] | 16 | 279 | |

| Author (Year) | PageRank | Local Citation | Global Citation |

| Welford and Frost (2006) [43] | 0.0391 | 18 | 101 |

| Zsidisin and Siferd (2001) [46] | 0.0334 | 11 | 220 |

| Rao and Holt (2005) [39] | 0.0325 | 30 | 616 |

| Rao (2002) [38] | 0.0281 | 34 | 294 |

| Simpson and Power (2005) [47] | 0.0222 | 8 | 176 |

| Yu (2008) [48] | 0.0221 | 7 | 70 |

| Reuter et al. (2010) [24] | 0.0210 | 10 | 124 |

| Zsidisin and Hendrick (1998) [49] | 0.0208 | 2 | 95 |

| Ponte and Gibbon (2005) [50] | 0.0186 | 2 | 318 |

| Simpson et al. (2007) [51] | 0.0173 | 8 | 175 |

| Cluster 1 (20 Papers) |

| Zsidisin and Siferd (2001) [46] |

| Simpson and Power (2005) [47] |

| Zsidisin and Hendrick (1998) [49] |

| Simpson et al. (2007) [51] |

| Theyel (2001) [58] |

| Wycherley (1999) [59] |

| Kleindorfer et al. (2005) [60] |

| Pagell et al. (2010) [61] |

| Vachon (2007) [62] |

| Pullman et al. (2009) [63] |

| Cluster 2 (26 Papers) |

| Welford and Frost (2006) [43] |

| Yu (2008) [48] |

| Reuter et al. (2010) [24] |

| Ponte and Gibbon (2005) [50] |

| Pedersen and Andersen (2006) [64] |

| Preuss (2009) [65] |

| Maignan et al. (2002) [66] |

| Lund-Thomsen (2008) [25] |

| Jiang (2009) [67] |

| Park and Stoel (2005) [68] |

| Cluster 3 (12 Papers) |

| Rao and Holt (2005) [39] |

| Rao (2002) [38] |

| Min and Galle (2001) [69] |

| Geffen and Rothenberg (2000) [45] |

| Rao (2005) [70] |

| Drumwright (1994) [71] |

| Nawrocka (2008) [72] |

| Green et al. (1996) [73] |

| Kogg (2003) [74] |

| Chien and Shih (2007) [75] |

| Cluster 4 (8 Papers) |

| Noci (1997) [40] |

| Yeh and Chuang (2011) [76] |

| Handfield et al. (2002) [37] |

| Lee et al. (2009) [77] |

| Kannan et al. (2013) [78] |

| Nagel (2003) [79] |

| Awasthi et al. (2010) [80] |

| Govindan et al. (2013) [27] |

| Cluster 5 (10 Papers) |

| Koplin et al. (2007) [44] |

| Carter (2005) [22] |

| Ciliberti et al. (2008) [81] |

| Carter and Jennings (2002) [41] |

| Carter (2004) [82] |

| Carter et al. (2000) [83] |

| Carter (2000) [84] |

| Awaysheh and Klassen (2010) [85] |

| Barrientos and Smith (2007) [86] |

| Andersen and Skjoett-Larsen (2009) [87] |

| Cluster Title | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. GS 1 practice and environmental performance | International purchasing/supply management practice and its influence on firm’s environmental performance using empirical research methodologies of case study and survey |

| 2. Social sustainability/ethical sourcing practice in GS | Social sustainability-related practices such as CSR 2, supplier management in relation to ethical sourcing standards, social/labour aspects of suppliers’ code of conduct practices using the empirical research methodologies of case study and survey |

| 3. Environmental evaluation criteria and certification | The effects of the adoption of “green” practice in purchasing/supply management and ISO14001 certification, e.g., green purchasing and greening the supply chain management using empirical methods |

| 4. Fuzzy modeling of environmental practice in GS | Fuzzy multiple selection criteria of international suppliers in environmental purchasing practice, using pure quantitative modelling analysis approach |

| 5. Effects of environmental and social sustainability practice on economic performance | The effects of social and/or environmental practice in GS on the economic performance of international companies using both empirical and modelling methods |

| Year | Number of Published Articles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | |

| 1994 | 1 | ||||

| 1995 | |||||

| 1996 | 1 | ||||

| 1997 | 1 | ||||

| 1998 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1999 | 1 | ||||

| 2000 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 2001 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 2002 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2003 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 2004 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 2005 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| 2006 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 2007 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| 2008 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| 2009 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2010 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2011 | 1 | ||||

| 2012 | 2 | ||||

| 2013 | 2 | ||||

| Total | 20 | 26 | 12 | 8 | 10 |

| Category | Gap/Issue | Research Direction |

|---|---|---|

| Discipline base | Social issue lack OM 1/SCM 2 works | Investigating socially sustainable practices from an OM/SCM point of view |

| Research method | Dominated by case and survey | Using secondary data sources for the sustainable impacts analysis of global sourcing. |

| Industry sector | Focus on manufacturing and labor-intensive industry | Examining SGS 3 issues in service sectors |

| Geographic aspect | Comparison of differences between sourcing countries | Comparing the differences of SGS issues and cultural distance between countries |

| Unit of analysis | Focus on focal firm and supplier | Extending research focus into both multi-tier supply chain and multi-stakeholder outside the supply chain |

| Theoretical framework | Limited in interrelationship | Exploring interrelationships among the three dimensions of sustainability |

| Longitudinal/ snapshot | Little longitudinal study | Adopting longitudinal view while investigating the evolution and changes of SGS projects as well as their impact on performance |

| Underpinning theory | Dominated by four theories | Using diverse theories to investigate SGS issues or combine different theories together to explore research topics in this area |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, F.; Jiang, Y. Sustainable Global Sourcing: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030595

Jia F, Jiang Y. Sustainable Global Sourcing: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability. 2018; 10(3):595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030595

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Fu, and Yan Jiang. 2018. "Sustainable Global Sourcing: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis" Sustainability 10, no. 3: 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030595

APA StyleJia, F., & Jiang, Y. (2018). Sustainable Global Sourcing: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability, 10(3), 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030595