Consumer Intervention Mapping—A Tool for Designing Future Product Strategies within Circular Product Service Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Is the tool useful in enabling the development of scenarios exploring how the promotion of resource efficient product lifecycles can be incorporated within future, more localised and responsive structures of manufacturing and product adaptation?

- Do the PSS scenarios that are generated depict non-conventional strategies or business models?

2. Background Research

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Justification of the Use of User Experience Research Methods

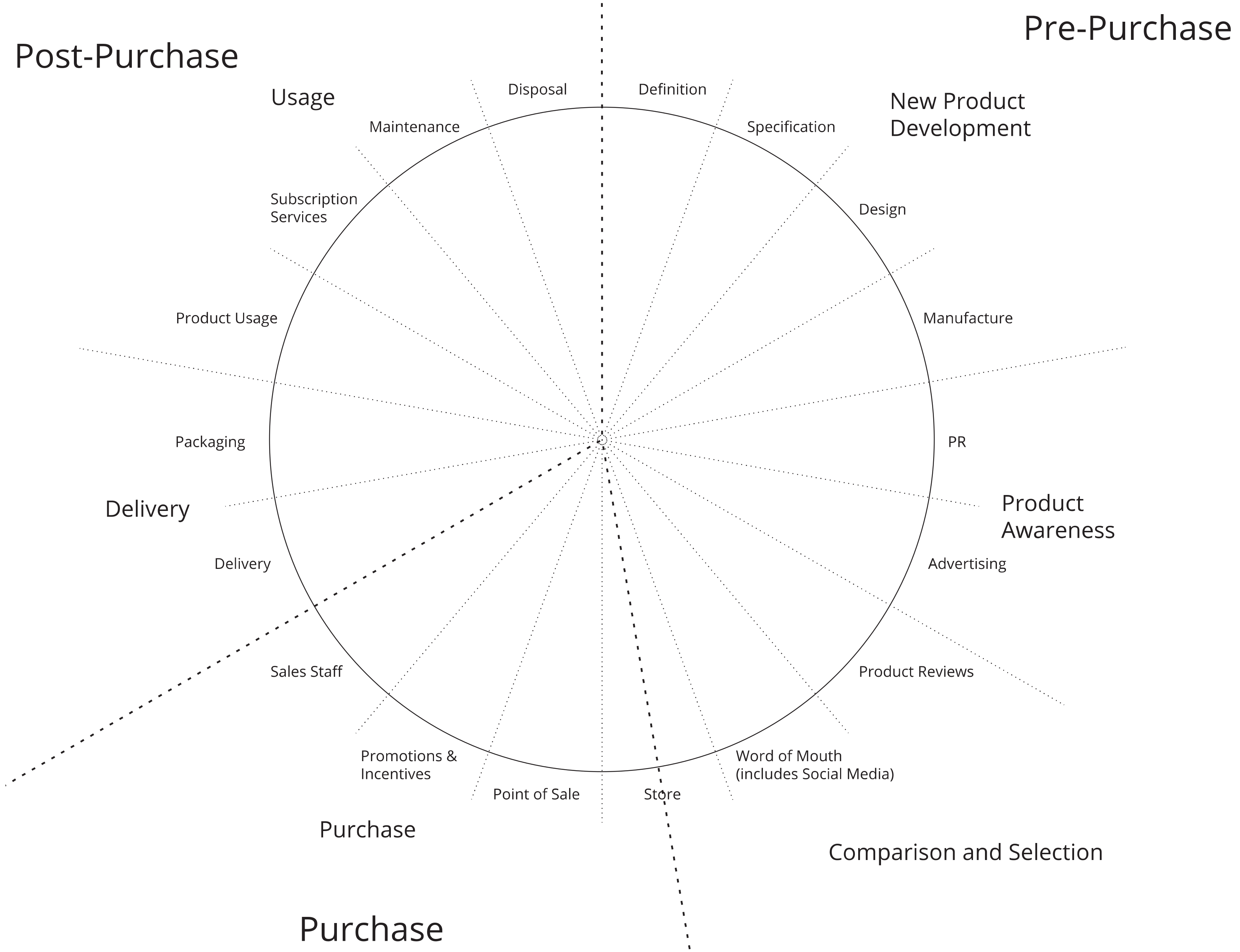

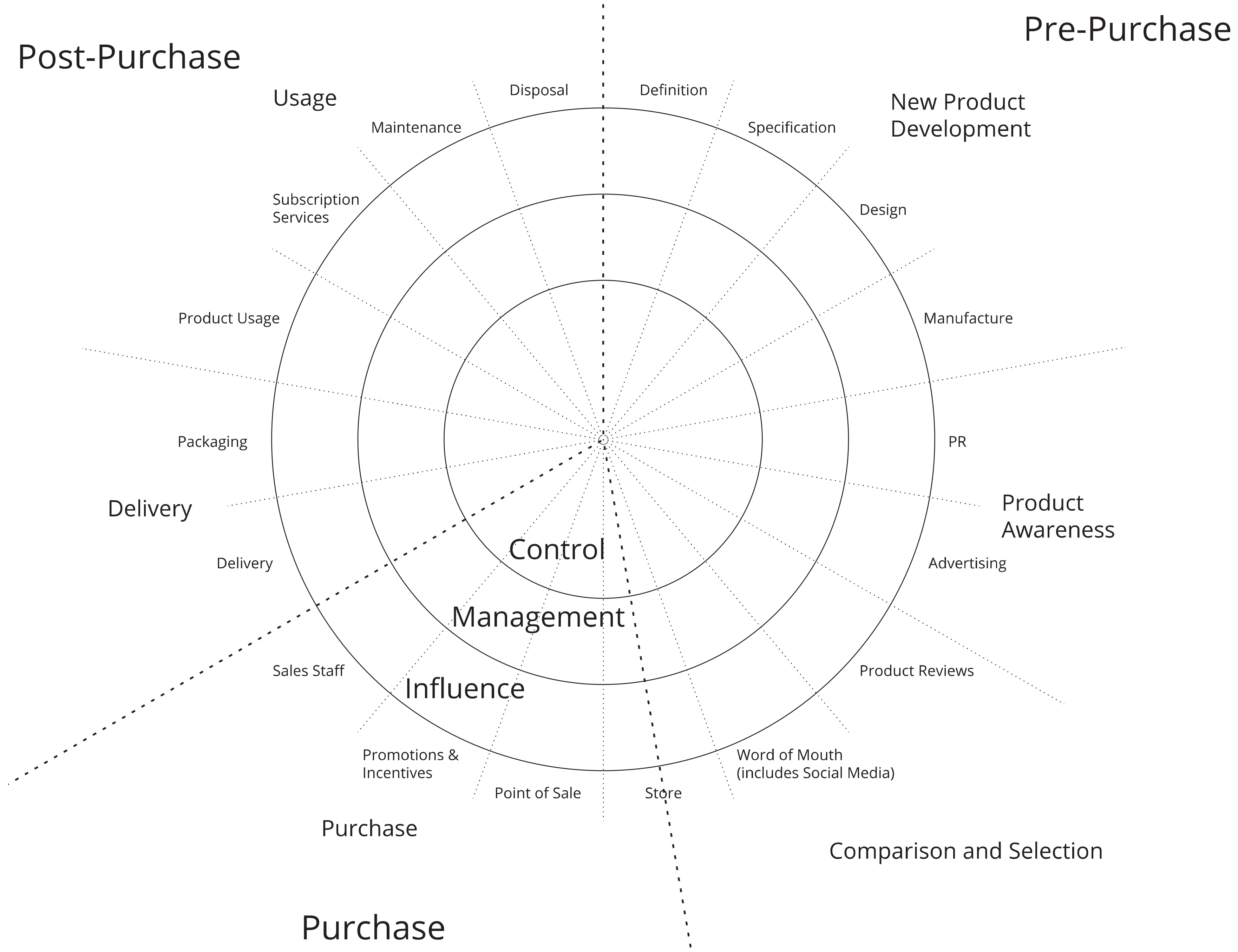

3.2. Construction of the Spatial Field of the Consumer Intervention Map

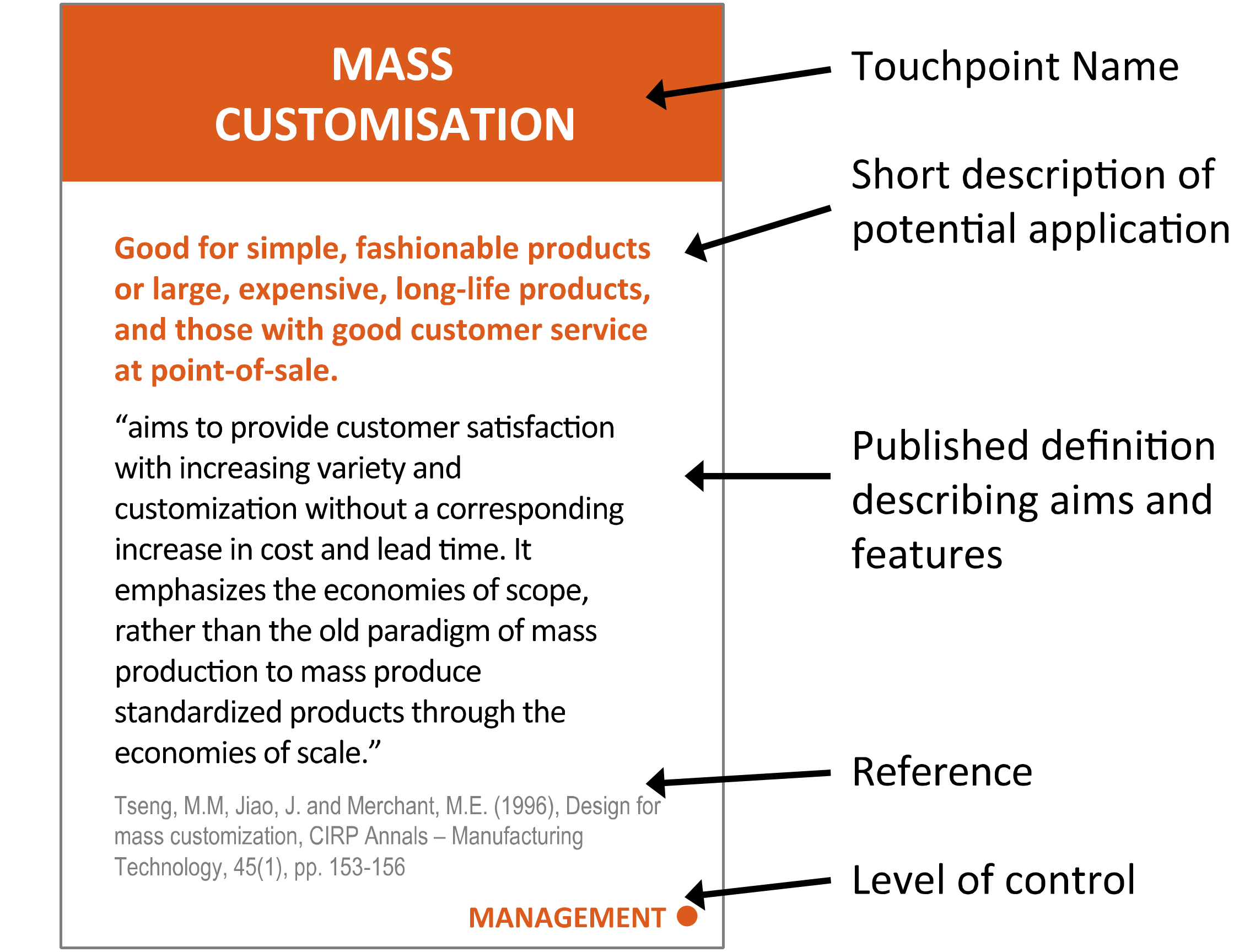

3.3. Population of the Consumer Intervention Map with Intervention Touchpoints

- (Bespoke);

- (Consumer OR User OR End-user) AND (Product Customi*ation OR Personali*ation);

- (Prosum* AND Grass Roots Innovation) AND NOT (Software OR Video OR Media);

- (Digital Fabrication OR 3D Print* OR Additive Manufactur*) AND (Makerspace OR Maker Movement OR Fab OR Fabbing OR Personal Fabricat* OR Personal Manufactur* OR Personal Produc*);

- (Digital Fabrication OR 3D Printing OR Additive Manufacturing) AND (Co-Production OR Social production OR social manufacturing);

- (Open Design);

- (Crowdsourc* OR Crowd Sourc*);

- (Participatory Design OR User Participation) OR (Cooperative Design) OR (Co Design OR Codesign OR Co-design) OR (Collaborative Design OR Co-creation)

- (DIY OR Do-It-Yourself)

- (Upcycl* OR Domestic Recycl* OR Household Recycl*) AND (Consumer Goods OR Consumer Products OR Domestic Products);

- (Repair) AND (Maintenance OR Servic*) AND (Consumer OR Customer OR User)

3.4. Validation and Testing

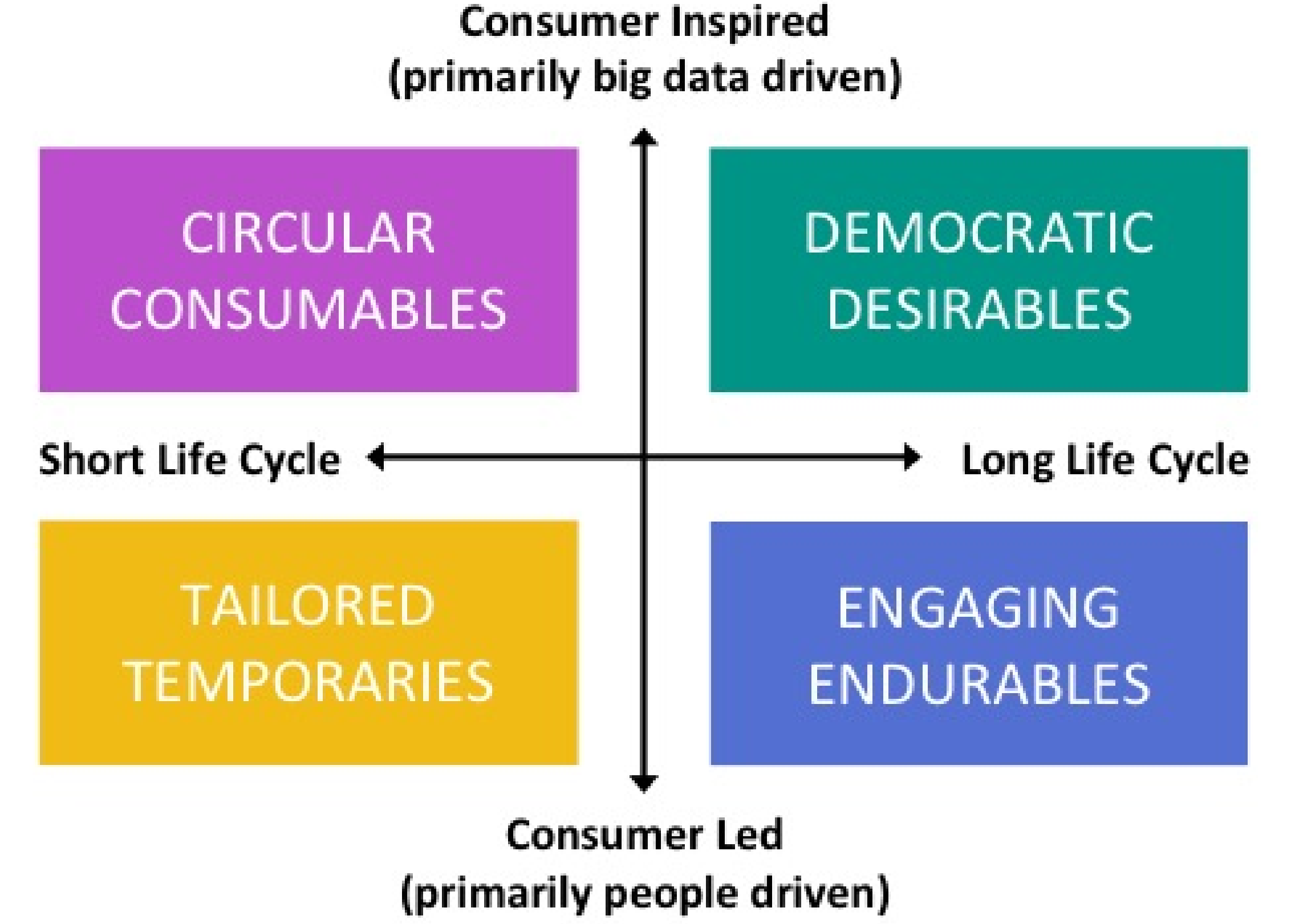

- Product Longevity. Within a CE, the length of product lifecycles will continue to vary greatly. Food, personal care and fashion products will have shorter lifecycles than consumer electronics, furniture and automotive products.

- Stakeholder Data. The type of stakeholder engagement in the PSS will vary, depending on the types of user data and mechanisms of interaction available. Consumer-inspired design will occur when large amounts of anonymised trend and usage data are available to help direct design; consumer-led design will occur when individual users are able to engage in the design and manufacture of their own, bespoke products.

- Circular Consumables (Short Life Cycle + Consumer-Inspired Design). In this scenario, circular products with short life cycles are produced, consumed, and recycled in a localised system. They are designed by gathering crowd sourced data to understand the needs of many. Technology development is focussed on the realisation of flexible and comprehensive recycling processes, and online systems that enable the collection and interpretation of these consumer preferences. Large multinational corporations use these big-data feedback mechanisms to dictate the products to be manufactured in localised flexible production systems.

- Democratic Desirables (Long Life Cycle + Consumer-Inspired Design). In this scenario, connected products with extended life cycles are produced, maintained and exchanged in a localised system. They are designed by monitoring life cycle data collected from embedded sensors. Technology development is focussed on realising flexible systems of supply and assembly, and in mechanisms that encourage simple maintenance and upgrade. Large companies gather big-data in real time to understand trends and behaviours and translate these into targeted offerings a localised branches and assembly centres.

- Tailored Temporaries (Short Life Cycle + Consumer-Led Design). In this scenario, circular products with short life cycles are personalised, used, and recycled in a localised system. They are designed by individual consumers who tailor their products through dedicated online portals. Technology development is focussed in the realisation of flexible production, recovery and recycling processes that facilitate these new consumer-centric business models. Businesses of various scales work with end users in both online and physical portals to enable customisation and production of their products locally.

- Engaging Endurables (Long Life Cycle + Consumer-Led Design). In this scenario, durable products with very long-life cycles are crafted and exchanged in localised systems. They are designed by individual customers who work with the makers to customise their purchases. Technology development is focussed in platforms to facilitate consumer engagement and co-design, and build local networks of makers, maintainers and exchangers. Local businesses work with end users through apps, service provision, and physical purchase and repair points.

4. Findings

- Was the tool useful in facilitating the task given to workshop participants?

- Did the PSS scenarios that were generated depict non-conventional strategies or business models?

- An existing PSS that has been adapted to a CE paradigm.

- An existing CE PSS that has been applied to a new product concept.

- Life Cycle Stages: Most PSS lifecycles have concentrated stakeholder intervention activity in the right-hand side of the spatial field (Pre-Purchase). This is the area conventionally occupied by an organisation’s internal stakeholders, utilising data on users to provide what the business believes its customers want or need. Visions of circular PSS lifecycles that place consumer interventions in this space suggests that workshop participants believe RdM will challenge the traditional distinctions between manufacturer, designer and consumer. In contrast the bottom left hand quadrant of the spatial field (Purchase and Delivery) has remained relatively unpopulated in all PSS lifecycles. This implies that participants found it difficult to imagine the applicability of a CE approach to this area of the map and suggests there may be new business opportunities which remain relatively unexplored. Many of the new touchpoints created by the groups were in the Post-Purchase phase, suggesting participants had difficulty matching their visions of a future PSS with current understandings of stakeholder interventions during ownership. Again, this indicates the potential for new areas of business opportunity.

- Organisational Control: Few PSS lifecycle diagrams have placed intervention points close to the centre (and therefore under complete control of the company). During the mapping exercise, groups often initially placed many cards around the outside of the spatial field, indicating interventions over which the organisation had no control or influence. However, when creating the final version of the lifecycle (Figure 10), these outlying touchpoints were used less frequently. Most stakeholder intervention therefore takes place in the central ring, under the management of the organisation, but outside of its complete control. It should be noted however, that placement of intervention points is likely to have been influenced by those stakeholders represented in the workshop: by their roles within a company or organisation and their knowledge of current legislation. This is a limitation that should be addressed in future work to refine the tool.

- Journey Start Points: When reviewing all scenarios, it is noticeable that many lifecycles do not begin in the Pre-Purchase phase usually assumed within CRM. This was again an unexpected development, but on reflection corresponds very well with the logic of circular design. In a theoretically perfect CE, where no resources are lost from the system [5], any point in the lifecycle can be the first intervention point for a particular stakeholder.

- Intervention Point Positioning: When creating the PSS lifecycles, a number of groups moved the position of an intervention touchpoint to a different position on the spatial map, for example ‘Self Assembly’ moved from ‘Packaging’ to ‘Store’. This was an unexpected outcome but indicates that participants did not feel the tool was over-constraining, and were prepared to question some of its assumptions. It also demonstrates the flexibility of the tool in terms of suggesting new instances of existing intervention touchpoints; for example, one scenario moved the ‘Social Media Commentary’ touchpoint to place it within ‘Product Usage’, to describe a product that tweeted about its status independently of its user.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation and IDEO. The Circular Design Guide. 2017. Available online: https://www.circulardesignguide.com/ (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Papanek, V. Design for the Real World; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, M.; de los Rios, C.; Rowe, Z.; Charnley, F. A conceptual framework for circular design. Sustainability 2016, 8, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, I. Evolution of design for sustainability: From product design to design for system innovations and transitions. Des. Stud. 2016, 47, 118–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, M.C.; Bakker, C.A.; Jan Hultink, E. Product design in a circular economy: Development of a typology of key concepts and terms. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy—Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2013; Volume 1, Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation-Towards-the-Circular-Economy-vol.1.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- European Commission. Circular Economy, Closing the Loop—Helping Consumers Choose Sustainable Products and Services; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/circular-economy-factsheet-consumption_en.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. New Circular Design Guide Launched by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and IDEO at Davos; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/news/new-circular-design-guide-launched (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- RSA. The Great Recovery—Investigating the Role of Design in the Circular Economy; RSA: London, UK, 2013; Available online: https://www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/reports/the-great-recovery (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC). Re-Distributed Manufacturing Call for Networks. Available online: https://epsrc.ukri.org/files/funding/calls/2014/re-distributed-manufacturing-call-for-networks/ (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Rosen, M.A.; Kishawy, H.A. Sustainable manufacturing and design: Concepts, practices and needs. Sustainability 2012, 4, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhao, Y.F. Sustainable design for additive manufacturing through functionality integration and part consolidation. In Handbook of Sustainability in Additive Manufacturing; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 101–144. [Google Scholar]

- Petrick, I.J.; Simpson, T.W. 3D printing disrupts manufacturing: How economies of one create new rules of competition. Res. Technol. Manag. 2013, 56, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Liu, P.; Mokasdar, A.; Hou, L. Additive manufacturing and its societal impact: A literature review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 67, 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J.P.L.; Schifferstein, H.N.J. Design strategies to postpone consumers’ product replacement: The value of a strong person-product relationship. Des. J. 2005, 8, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, S.H.; Partanen, J.; Holmströ, J. Additive manufacturing in the spare parts supply chain. Comput. Ind. 2014, 65, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtala, C. Addressing sustainability in research on distributed production: An integrated literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellens, K.; Baumers, M.; Gutowski, T.G.; Flanagan, W.; Lifset, R.; Duflou, J.R. Environmental dimensions of additive manufacturing: Mapping application domains and their environmental implications. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, S49–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdas, F.; Juraschek, M.; Thiede, S.; Herrmann, C. Life cycle assessment of 3D printed products in a distributed manufacturing system. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, S80–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Germani, M.; Zamagni, A. Review of ecodesign methods and tools. Barriers and strategies for an effective implementation in industrial companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendeville, S.M.; O’Connor, F.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Bakker, C. Uncovering ecodesign dilemmas: A path to business model innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 1327–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Jan Hultink, E. Design thinking to enhance the sustainable business modelling process—A workshop based on a value mapping process. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1218–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyl, B.; Vallet, F.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Real, M. The integration of a stakeholder perspective into the front end of eco-innovation: A practical approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, M.; Campbell, I. A classification of consumer involvement in new product development. Proc. DRS 2014, 2014, 1582–1598. [Google Scholar]

- França, C.L.; Broman, G.; Robèrt, K.-H.; Basile, G.; Trygg, L. An approach to business model innovation and design for strategic sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hobson, K.; Lynch, N.; Lilley, D.; Smalley, G. Systems of practice and the Circular Economy: Transforming mobile phone product service systems. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 26, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzoli, C.; Ceschin, F.; Diehl, J.C.; Kohtala, C. New design challenges to widely implement ‘Sustainable Product–Service Systems’. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, M. Spimes and speculative design: Sustainable product futures today. Strateg. Des. Res. J. 2017, 10, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, S. iOS 11.3 update breaks iPhone 8 devices with third party-repaired screens. The Guardian. 10 April 2018. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/apr/10/iphone-8-ios-113-breaks-smartphones-third-party-repaired-screens-apple (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Dhebar, A. Toward a compelling customer touchpoint architecture. Bus. Horiz. 2013, 56, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.M.; Rankin, Y.A.; Bolinger, J. Client touchpoint modeling: Understanding client interactions in the context of service delivery. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 979–982. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D.; Neilsen, J. The Definition of User Experience (UX). Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/definition-user-experience/ (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- H.M. Government. Customer Journey Mapping: Guide for Practitioners. 2007. Available online: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/media/123970/journey_mapping1.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- SilverTech. Mapping the Customer Journey (White Paper). Available online: https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/321221/Mapping%20the%20Customer%20Journey%20Whitepaper.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Tincher, J. Using Customer Journey Maps to Improve Health Insurance Customer Loyalty. FC Business Intelligence Executive Briefing. Available online: https://heartofthecustomer.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/White-Paper-Health-Insurance-Create-Loyalty-through-an-Improved-Customer-Journey-White-Paper.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Andrews, J.; Eade, E. Listening to students: Customer journey mapping at Birmingham City University Library and learning resources. New Rev. Acad. Librariansh. 2013, 19, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.M.; Dunn, M. Building the Brand-Driven Business: Operationalize Your Brand to Drive Profitable Growth; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.C.; Mauborgne, R. Knowing a winning business idea when you see one. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohn, D.L. Brand Touchpoint Wheel—Worksheet. 2013. Available online: http://deniseleeyohn.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/WGBD-Download-Brand-Touchpoint-Wheel-Worksheet.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Stein, A.; Ramaseshan, B. Towards the identification of customer experience touch point elements. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 30, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, H.L.; Szabo, I.; le Brun, L.; Owen, I.; Fletcher, G.; Hill, M. Evidence Based Scoping Reviews. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Eval. 2011, 14, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Durance, P.; Godet, M. Scenario building: Uses and abuses. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 1488–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, W.; Wau, J. (Eds.) Sociology of the Future: Theory, Cases and Annotated Bibliography; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Ringland, G. Scenarios in Public Policy; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, R.; Wilkinson, A. Rethinking the 2 × 2 scenario method: Grid or frames? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 86, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wölfel, C.; Merritt, T. Method card design dimensions: A survey of card-based design tools. In Proceedings of the IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Cape Town, South Africa, 2–6 September 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 479–486. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, A.; Raby, F. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Angheloiu, C.; Chaudhuri, G.; Sheldrick, L. Future Tense: Alternative Futures as a Design Method for Sustainability Transitions. Des. J. 2017, 20, S3213–S3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broms, L.; Wangel, J.; Andersson, C. Sensing energy: Forming stories through speculative design artefacts. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, M. What will designers do when everyone can be a designer? In Design for Personalisation; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, K.; Lynch, N. Diversifying and de-growing the circular economy: Radical social transformation in a resource-scarce world. Futures 2016, 82, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Workshop 1 Imperial College, London Nov. 2016 | Workshop 2 IMechE, London June 2017 | Workshop 3 PLATE Conference, TU Delft Nov. 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants Total | 17 | 15 | 21 |

| Industry Professionals | 3 | 6 | 0 |

| Academics | 4 | 4 | 9 |

| Post-graduate Students | 10 | 5 | 9 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Duration | 4 h | 2 h | 90 min |

| Task Description | Within one of the four boundary condition scenarios (Circular Consumables, Democratic Desirables, Engaging Endurables or Tailored Temporaries): Develop a future PSS scenario and describe the product’s lifecycle Develop a scenario-specific PSS lifecycle diagram Present to other participants | Within one of the four boundary condition scenarios (Circular Consumables, Democratic Desirables, Engaging Endurables or Tailored Temporaries): Develop a future PSS scenario and describe the product’s lifecycle Develop a scenario-specific PSS lifecycle diagram Present to other participants | Within one of two boundary condition scenarios (Democratic Desirables or Engaging Endurables): Develop a scenario-specific PSS lifecycle diagram Present to other participants |

| Outputs | Worksheet 1: PSS scenario describing the product’s design, purpose, use and disposal. Worksheet 2: Consumer Intervention Map visualising the product’s lifecycle | Worksheet 1: PSS scenario describing the product’s design, purpose, use and disposal. Consumer Intervention Map visualising the product’s lifecycle | Worksheet 1: Consumer Intervention Map visualising the product’s lifecycle |

| Circular Consumables | Democratic Desirables | Engaging Endurables | Tailored Temporaries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Which Product? | Personalised Party Game Bundles Rental | Smart Kettle Service | Personalised Jumpers | Washing Liquid |

| Design phase description | Trend scanning for the company (with consumer as an observer) | Data collected locally from smart kettles is used by companies who share the insights | Prosumer designed across the lifecycle by consensus, with the designer as a facilitator | An online platform provides customisation choices of fragrance, formulation, format, etc. |

| Purchase phase description | Online marketplace for brokering and customising deal | Tier pricing is used as an incentive, based on the data shared with the companies | There is a perception of individuality at initial purchase, with multiple avenues for swapping and repurchasing second hand | User forum allows customers to review and rate creations, or to create a store to allow others to purchase their product |

| Use phase description | During the special event the product is used and retained | Data is gathered to allow local maintenance to be scheduled as needed, and trust is built. Findings shared with legislative bodies | Different cycles of use with consumers engaged in re-design of a second life where needed | Subscription service provides automatic renewal and delivery of concentrated liquid |

| Disposal phase description | Collected by company for re-use and recycling where applicable | Data from use phase enables prediction of best end of life management options | Swap, resell, or unprint/reprint to make something new | Packaging taken back for cleaning and reuse |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sinclair, M.; Sheldrick, L.; Moreno, M.; Dewberry, E. Consumer Intervention Mapping—A Tool for Designing Future Product Strategies within Circular Product Service Systems. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062088

Sinclair M, Sheldrick L, Moreno M, Dewberry E. Consumer Intervention Mapping—A Tool for Designing Future Product Strategies within Circular Product Service Systems. Sustainability. 2018; 10(6):2088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062088

Chicago/Turabian StyleSinclair, Matt, Leila Sheldrick, Mariale Moreno, and Emma Dewberry. 2018. "Consumer Intervention Mapping—A Tool for Designing Future Product Strategies within Circular Product Service Systems" Sustainability 10, no. 6: 2088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062088

APA StyleSinclair, M., Sheldrick, L., Moreno, M., & Dewberry, E. (2018). Consumer Intervention Mapping—A Tool for Designing Future Product Strategies within Circular Product Service Systems. Sustainability, 10(6), 2088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062088