1. Introduction

With the clear trend of urban sprawl worldwide, more than half of the world’s population today has crowded into cities [

1]. Complex transport systems are developed or under development to meet the growing traffic demand in many metropolises [

2]. As the road network becomes more and more congested, a lot of citizens begin to choose public transit for commuting [

3]. Unfortunately, urban traffic resources are insufficient, so it is impossible for public transport to service any two points in the cities by a direct and efficient line. Many commuters may need to combine several modes at a transport node [

4]. This is called transfer. Numerous citizens tend to choose transfer commuting in public transport systems for efficiency, convenience, comfort, or maybe safety [

5]. Moreover, comparing with commuting by car, using transfer in public transit system can also reduce the traffic emissions and help protect the environment. Thus, it is a sustainable choice for commuters to take. However, transfer disutility always makes it less competitive compared to a direct way [

6,

7].

A lot of efforts have been made on studying transfer disutility [

8,

9,

10,

11], while some of the studies are focused on the users’ perceptions of transfers from various perspectives. Desiderio [

12] pointed out that multimodal transport nodes also have great impact on the urban transport system as they may influence the users’ experience of travelling or even change users’ travel behavior. Peek and van Hagen [

13] identified layout and visible presence of staff as key aspects while safety and comfort as important request to users’ satisfaction. Cheng and Tseng [

14] explored the effects of perceived values, free bus transfer, and penalties on travelers’ intention. Hernandez and Monzon [

15] investigated the key factors that influence the travelers’ satisfaction during transfer using Principal Component Analysis. Variables of eight categories, including travel information, way-findings information, time and movement, access, comfort and convenience, image and attractiveness, safety and security, and emergency situation are considered in their studies.

Furthermore, personal and trip features are taken into consideration as transfer disutility is not a constant to different travelers [

16]. Type of access or egress mode, travel length, gender, age, income, and education all may make a difference to perceptive transfer disutility [

17,

18,

19].

However, these studies still fail to explain why travelers with similar features will make different decisions on the choices of transfer commuting. Fortunately, transportation researchers have been paying more attentions on travelers’ attitudes in recent decades. Outwater et al. [

20] indicated that market segmentation using attitudinal survey to identify potential markets will help develop corresponding policies to attract more transit ridership. Anable [

21] identified the potential mode switchers based on a multi-dimensional attitudinal survey. In that research, six distinct groups are segmented, indicating that different groups need to be serviced in different ways. Shiftan et al. [

22] clustered the transit market into eight groups by three attitudinal factors including the sensitivity to time, need for a fixed schedule, and willingness to use public transit using a market segmentation approach. Li et al. [

23] considered another five factors including need for flexibility, desire for comfort, desire for economy, environmental awareness, and perception towards bicycling when conducting the bicycle commuting market segmentation. Zhang et al. [

24] also put the personality in market segmentation approach as a key factor to analyze the shared parking willingness.

Individuals’ attitudes are commonly collected by stated preference (SP) survey [

25,

26,

27]. As attitudinal factors are usually unobserved, a series of multi-dimensional questions (statements) should be asked to sort out the key factors using the structural equation modeling (SEM) method with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) [

28]. The SEM performs very well in identifying the underlying factors and analyzing the correlations among key factors [

20,

22,

29,

30]. Moreover, the value of underlying factors can be used later in clustering to segment the market using K-means clustering method as it is efficient, practical, and well measured [

31]. This research aims to give different suggestions to serving different groups of commuters to improve the policies or strategies effectivity and attract potential transfer commuters. Thus, after obtaining the transfer commuting market segmentation results, characteristics of each segments will be analyzed via cross-comparison. Finally, the corresponding policies or strategies to persuade potential transfer commuters will be proposed to increase the transfer ridership.

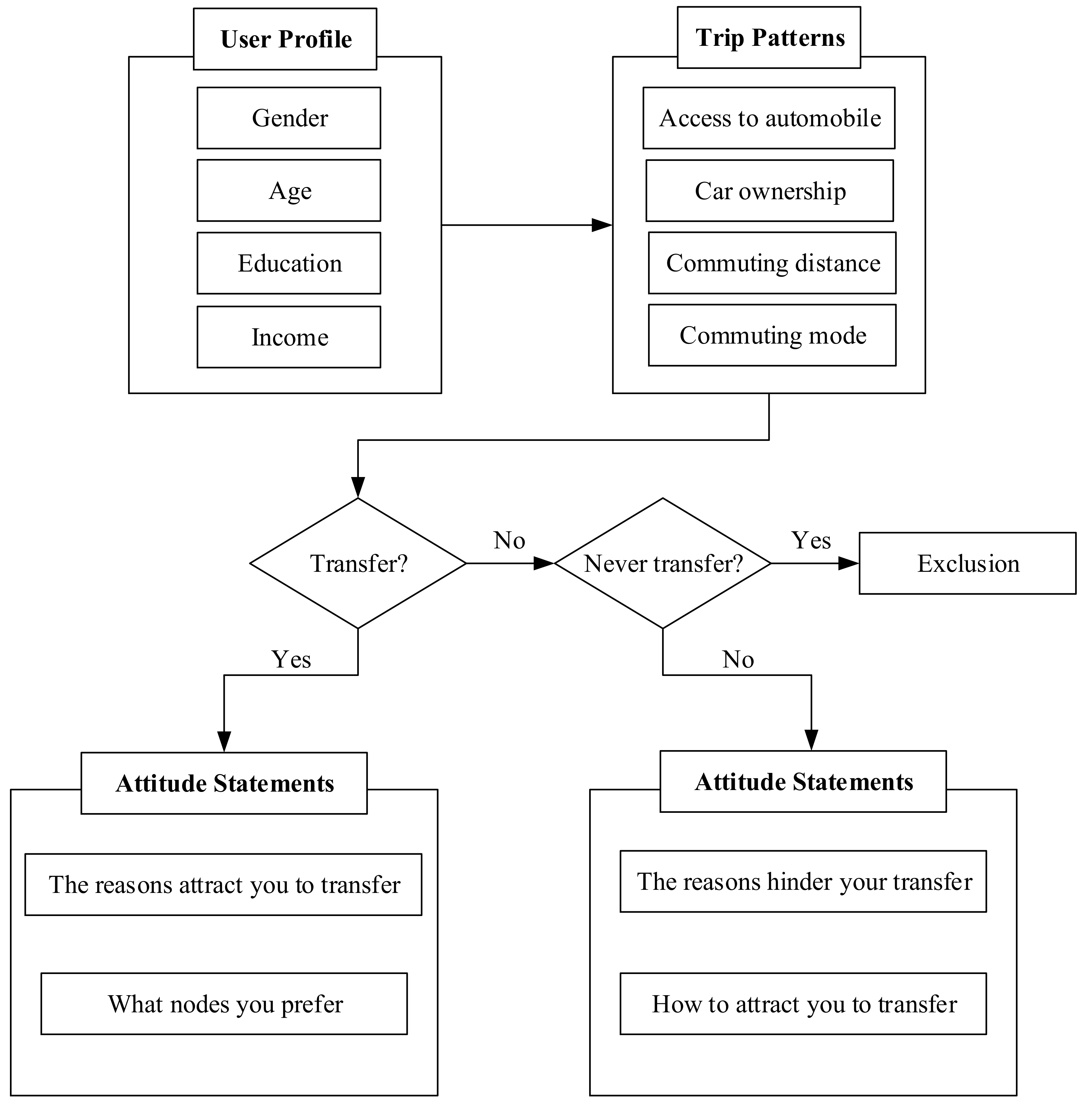

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the market segmentation approach in detail used in this study.

Section 3 describes a case study including the data collection and analysis.

Section 4 gives the results estimated by the market segmentation approach.

Section 5 discusses the estimation results and proposes some policies and strategies.

Section 6 is a summary section and presents some expectations in future works.

4. Results

4.1. Underlying Attitudinal Factors Verification

At the beginning of the research, five specific underlying factors including sensitivity to time (Q1–Q2), need for flexibility (Q3–Q6), desire for comfort (Q7–Q10), desire for less energy cost (Q11–Q13), and willingness to transfer (Q14–Q16) have been already set and their correlated statement variables are designed as shown in

Table 5.

Linear correlation analysis was conducted among the variables obtained from the RP survey and the SP survey to identify the key personal or socio-economic attributes influencing the transfer commuting behavior. Finally, two real variables, the number of car ownership (QI) and the main travel mode (QII) show a strong relationship with transfer commuting attitudinal variables. Then these two variables was identified as one factor via the EFA called car ownership.

Six underlying factors were picked out from 18 observed variables using Amos 25.0, which is a professional software for processing SEM models. The goodness of fit index (GFI) is 0.810, higher than 0.8, which means more than 80% of the correlations among factors and variables can be well explained by the model.

Table 5 also presents the factor coefficient, standard error and critical ratio results. All the values of critical ratio are above 2.0, indicating that these variables have significant impact on transfer commuting attitudes.

4.2. Correlations among Factors and Variables

The SEM structure is presented in

Figure 5. The weighted coefficient estimations of variables and factors are also shown in

Figure 5. The value of RMR, GFI, and RMSEA of the SEM is 0.079 (less than 0.08 [

42]), 0.91 (greater than 0.9 [

41]), and 0.048 (close to 0 [

41]) while the value of CFI is 0.90, very close to the ideal value 0.95 [

42]. These indexes verify that the SEM in this study fits well. The numbers on the links are coefficients between variables and factors or factors and factors estimated by the SEM. And the results of the SEM are significant at a 95% confidence level.

As shown in

Figure 5, the willingness to transfer is dependent of car ownership while the other four factors are respectively related to the car ownership and the willingness to transfer. The need for flexibility, the desire for comfort, and the desire for less energy cost have a significantly positive impact on the car ownership, indicating the need for flexibility and the desire for comfort and saving energy would urge people to buy private cars and commute by car. The sensitivity to time is passively related to car ownership, which means commuting by car is recognized as an unreliable choice as traffic congestion is severe during commuting hours in Nanjing.

The car ownership and the desire for comfort have a negative impact on the willingness to transfer while the sensitivity to time and the need for flexibility have a high positive relationship with the willingness. Four main conclusions can be drawn from the SEM structure. The first one is if transfer can provide higher time reliability, more commuters will prefer transfer commuting. The second one is that the more flexible the transfer service is the more transfer commuters will be attracted. The third one is that the transfer process brings more uncomfortableness to commuters compared to direct lines. The last one is that commuters who own cars and have car preferences would be less prone to choose transfer.

4.3. Transfer Market Segmentation Results

The coefficients of variables estimated in SEM are used to calculate the value of each factors. The score of each factor is standardized into 0 to 5. As the sensitivity to time, the need for flexibility and the desire for comfort are significantly related to the willingness to transfer, these three factors are used to conduct K-means clustering. The optimal K value is identified by the value of SSE, as shown in

Figure 6. In this study, number of clusters (K) should be valued six.

The centroid of the six segments are presented in

Table 6. The words in the brackets represent the level of scores, high level: >4.0, moderate level: 3.0–4.0 and low level: <3.0. Thus, six segments of transfer market are summarized as follows:

Segment 1 (S1) is a group of individuals which have a low willingness to transfer. They have a low sensitivity to time, a low need for flexibility and a low desire for comfort.

Segment 2 (S2) is a group of individuals which have a moderate willingness to transfer. They have a high sensitivity to time, a moderate need for flexibility, and a low desire for comfort.

Segment 3 (S3) is a group of individuals which have a moderate willingness to transfer. They have a moderate sensitivity to time, a high need for flexibility, and a moderate desire for comfort.

Segment 4 (S4) is a group of individuals which have a moderate willingness to transfer. They have a high sensitivity to time, a high need for flexibility, and a high desire for comfort.

Segment 5 (S5) is a group of individuals which have a high willingness to transfer. They have a high sensitivity to time, a low need for flexibility, and a moderate desire for comfort.

Segment 6 (S6) is a group of individuals which have a high willingness to transfer. They have a high sensitivity to time, a high need for flexibility, and a moderate desire for comfort.

5. Discussion of Results

The socio-economic characteristics of the six segments are also analyzed respectively to further study the difference among these six groups of non-transfer commuters (see

Table 7). All the transfer attitudinal preferences of the commuters in the S1 are low as their actual private car usage proportion for commuting is higher than the other five segments, indicating that they have a car preference. So, this group of commuters lack of potential to transfer commuting.

The S2, S3, and S4 have the same moderate willingness to transfer while their needs or desires for transfer service vary from each other. The S2 has a high sensitivity to time, a moderate need for flexibility, and a low desire for comfort.

Table 7 shows that more than 95% of the commuters in the S2 have an actual below 8 km commuting distance. As their commuting distance and time is short, their desire for comfort is low. And their actual car usage is much lower than the S1 while their bicycle usage is much higher. The S3 has a higher average income than the other five segments but it has a moderate sensitivity to time. The reason might be that the higher social position brings more money and the more flexible commuting schedule. This finding is consistent with several previous studies which reported that the attitudes often cut across socioeconomic groups [

21,

47]. More than 40% of commuters in the S3, as shown in

Table 7, actually commute by slow traffic, such as cycling and walking. The S4 has a higher average age than the other segments and the highest car ownership. These make the commuters in the S4 have a high need for flexibility and a strong desire for comfort.

The S5 and S6 have a high willingness to transfer.

Table 7 also tells that the S5 has the highest proportion of actual metro usage. Metro commuters always have a strong sensitivity to time and have a lower perceived transfer disutility than the commuters using other traffic modes. The commuters in the S6 have the lowest age of the six segments. The younger commuters have a stronger sensitivity to time and a greater need for flexibility while not that focus on the comfort. However, they still have a strong willingness to transfer as their perceived transfer disutility is much less than the elder commuters. In addition, comparing the low transfer willingness group with the high willingness one, a conclusion can be drawn that the better educated commuters have higher willingness to transfer.

6. Policy Implications

Since the commuters in the S1 have a quite low willingness to transfer, the S1 is extracted from the potential transfer commuters. The S2 and S4 have high sensitivity to time, so accurate real-time information of public transit online or at the transfer nodes may attract some private car users to using public transit or even transfer. Commuters in the S3 and S4 both have a high desire for transfer flexibility, indicating that the appearance of bike sharing promote the transfer willingness and the transfer nodes with higher transfer lines overlapping attract more commuters to transfer. Besides, the S4 also has a high desire for comfort, compared with the S6, higher desire for comfort makes the willingness to transfer lower, which suggests that service of level of transfer, including the walking environment, the seat availability and the transfer node capacity should be improved to reduce the commuters’ perceived transfer disutility.

Commuters in the S5 and S6 like commuters in the S2 and S3 also have high sensitivity to time. Thus, sensitivity to time is the most important factors for commuters to influence the willingness to transfer like many other studies reported [

11,

32]. Strategies on reducing the transfer time and improving the transfer time reliability could increase the transfer usage in the four segments (S2, S4, S5, and S6). From the perception of the desire for comfort, as current transfer comfort is poor, commuters’ desire for comfort shows a negative impact on the willingness to transfer. Though, only one segment shows a high desire for comfort currently, the desire for comfort will be more and more significant in the future with further improvement in living standards as Hernandez declared that comfort at a transfer node is a determining factor in the ease of making a transfer [

15].

7. Conclusions

In this study, the key factors and attributes that influence commuters’ transfer choices have been identified through a combined RP and SP survey conducted in Nanjing, China. According to the actual mode choice from RP data, the commuters are separated into two parts, actual transfer commuters and actual non-transfer commuters. Different attitudinal questions were asked to these two parts, respectively. To actual transfer commuters, there is no need to attract them to transfer but investigating their attitudes towards transfer can help us know better about the deficiencies in transfer systems. However, the actual non-transfer commuters are the potential transfer commuters. Market segmentation approach should be used to segment them into more detailed submarkets by several attitudinal factors and one socio-economic factor called car ownership, as this factor shows a strong relationship with the willingness to transfer in the factor analysis. Finally, six segments of the actual non-transfer commuters were acquired from the study and the socio-economic characteristics of each segment were analyzed.

The results of market segmentation show that the S1 is a group of individuals which have a low willingness to transfer, a low sensitivity to time, a low need for flexibility, and a low desire for comfort. These commuters are not considered as the potential transfer commuters since they have a strong car preference as presented in their socio-economic statistical results. Commuters in the S2, S3, and S4 have moderate willingness to transfer while in the S5 and S6 commuters have high willingness to transfer. Thus, these commuters are considered as the potential market switchers. Corresponding policy and strategy recommendations for each segment to promote the transfer commuting were proposed at last.

Since transfer behavior is very complex, this study only focuses on several factors that influence commuters transfer choices. Other types of attitudinal factors and socio-economic variables can be used to segment the transfer commuting market. Also, the methodology in this paper is not perfect. The SEM method only can measure the interrelation of factors and variables, but cannot analyze how and to what extent they will affect commuters’ transfer mode and route choices. Therefore, a lot of other interesting issues, such as which kind of transfer modes or transfer nodes will commuters prefer, can be taken into consideration in future works.