A Countryside to Sip: Venice Inland and the Prosecco’s Uneasy Relationship with Wine Tourism and Rural Exploitation

Abstract

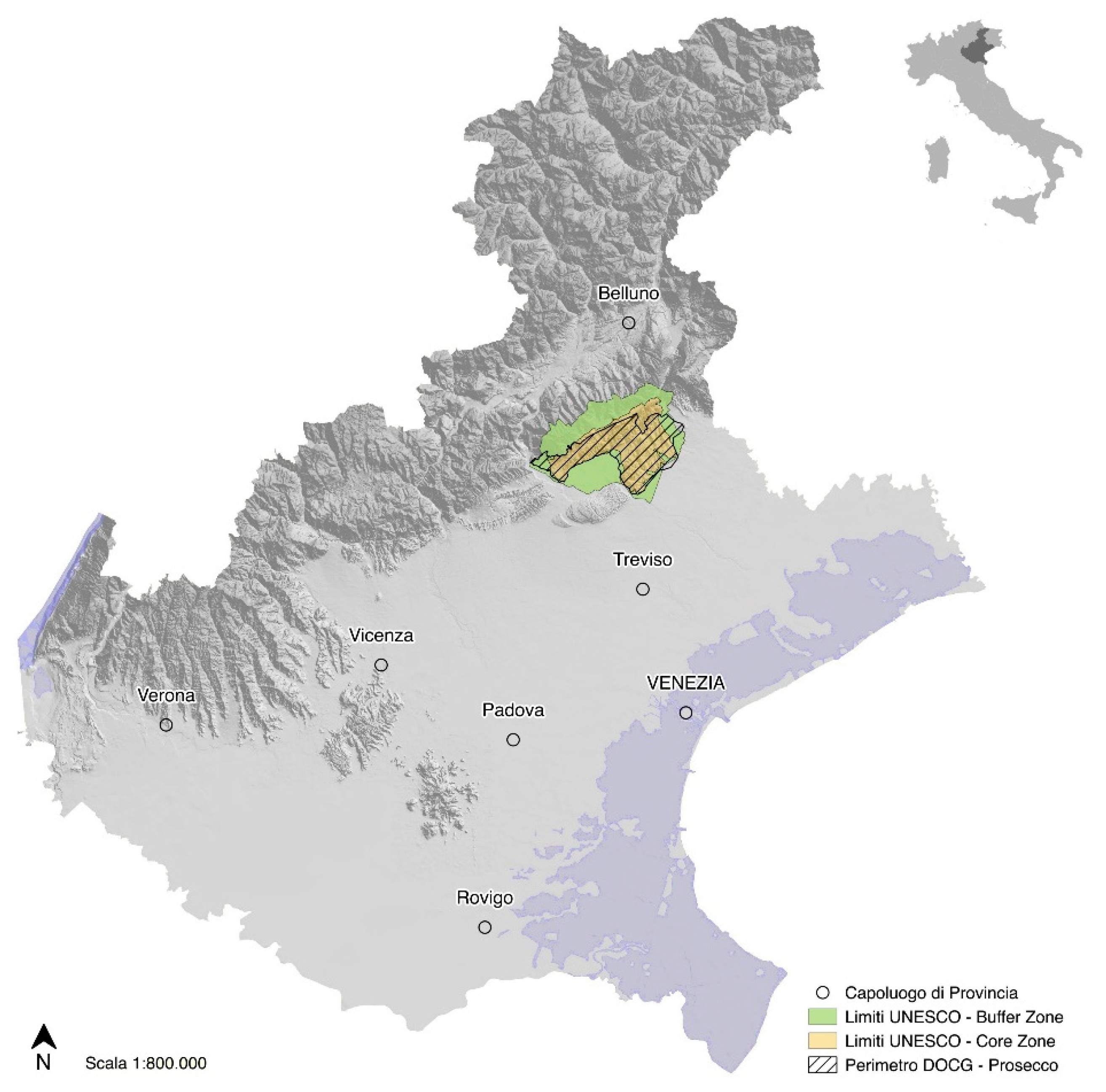

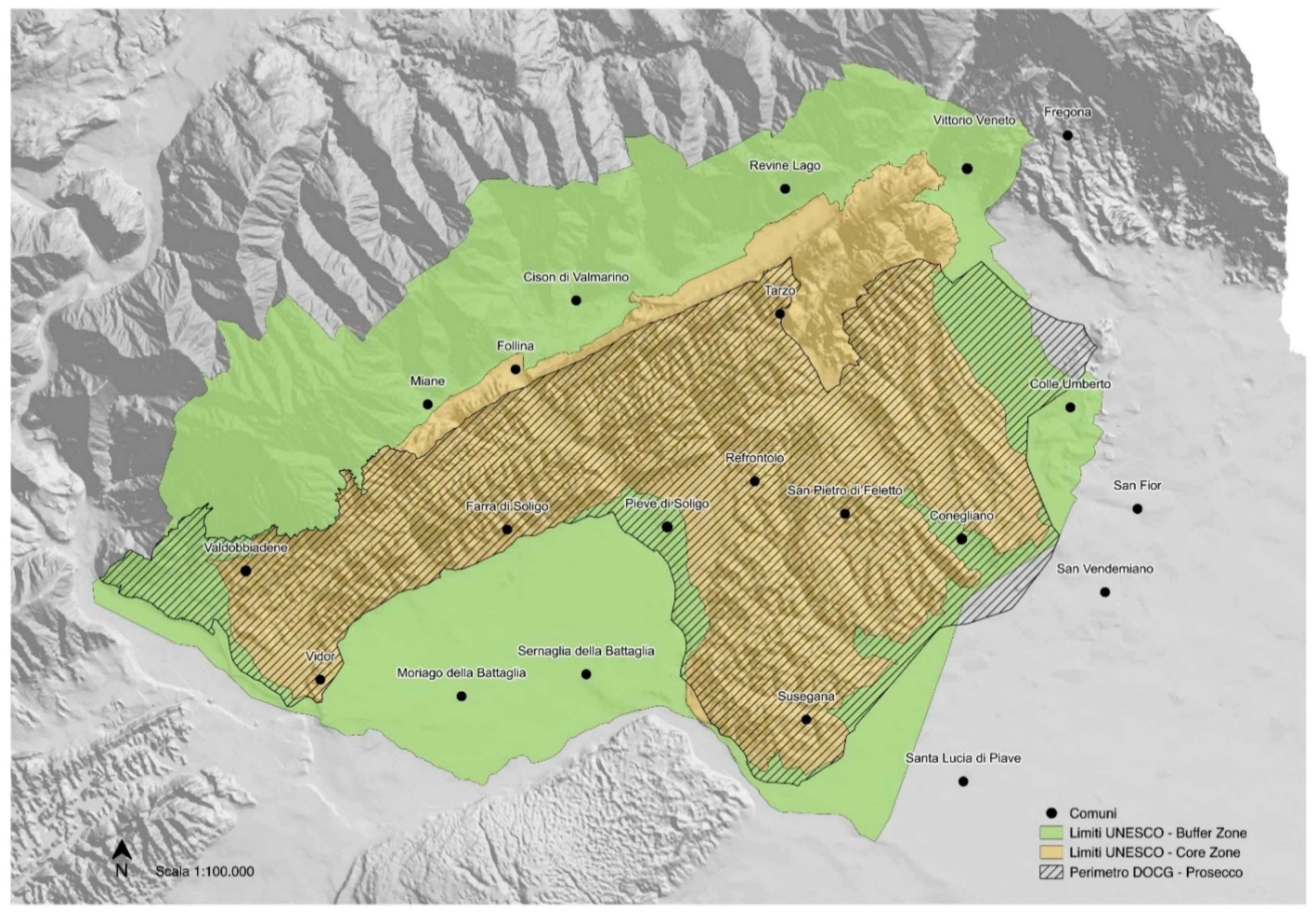

:1. Introduction: The ‘Prosecco Turn’ and Its Cultural Landscapes

2. The Venice Inland: From Traditional Agriculture to Urban Sprawl

3. Exploiting Rural and Wine Tourism

3.1. Discussing (Rural) Tourism

3.2. What about the Prosecco?

4. Environmental Impacts and the Growing Quest for Sustainability

5. Conclusions: Arcadian Legacies and the Charm of Wine Tourism

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cosgrove, D. Cultural Geography. In The Dictionary of Human Geography, 3rd ed.; Johnston, R.J., Gregory, D., Smith, D.M., Eds.; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1994; p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Soule, D. (Ed.) Urban Sprawl: A Comprehensive Reference Guide; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- OVSE. (Italian Economic Bubble Wine Observatory) 2014 Spumante Wines: Export wins hands down. More Spumante than Champagne Bottles Sold in the World. Available online: http://www.ovse.org/homepage.cfm?idContent=181 (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Tomasi, D.; Gaiotti, F.; Jones, G. The Power of the Terroir: The Case Study of the Prosecco Wine; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Vineyard Landscape of Piedmont: Langhe-Roero and Monferrato. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1390 (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- UNESCO. The Prosecco Hills of Conegliano and Valdobbiadene. Tentative List. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5566/ (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- Graham, B.; Howard, P. (Eds.) Heritage and Identity; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D. The Palladian Landscape; Leicester University Press: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, F. Prosecco Perché? Le Nobili Origini di un Vino Triestino; Luglio Editore: Trieste, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Balbi Valier, M.G. Per le Auspicatissime Nozze Bianchini-Dubois, in Segno di Affettuosa Amicizia e stima […] Lettera Sulle Coltivazioni di Pieve di Soligo; Longo: Treviso, Italy, 1868. [Google Scholar]

- Rorato, G. Il Prosecco di Conegliano-Valdobbiadene; Morganti: Verona, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, D.; Dalle Ceste, M.; Tempesta, T. (Eds.) I Paesaggi Vitati del Conegliano Valdobbiadene, Delle Pianure del Piave e del Livenza: Evoluzione e Legame con la Qualità del Vino; CRA-VIT: Treviso, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Whetzel, H.H. An Outline of the History of Phytopathology; W. B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1918. [Google Scholar]

- Dalmasso, G. Vini Bianchi Tipici dei Colli Trevigiani: Sottozone di Conegliano e Valdobbiadene; Longo e Zoppelli, Stazione Sperimentale di Viticoltura e Enologia: Treviso, Italy, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Vianello, A.; Carpenè, A. La Vite e il Vino in Provincia di Treviso; Loescher: Torino, Italy, 1874. [Google Scholar]

- Jacini, S. I Risultati Della Inchiesta Agraria. Relazione Pubblicata Negli Atti Della Giunta per la Inchiesta Agraria; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D. From Palladian Landscape to the Città Diffusa: the Veneto and Los Angeles. In European Landscapes and Lifestyles. The Mediterranean and Beyond; Roca, Z., Spek, T., Terkenli, T., Eds.; Edicôes Universitàrias Lusòfonas: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007; pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. 2018. Available online: http://www2.unwto.org/ (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Osservatorio Nazionale del Turismo—Data 2017. Available online: http://www.ontit.it/opencms/opencms/ont/it/stampa/in_evidenza/il_belpaese_chiude_il_2017_con_delle_presenze (accessed on 17 April 2018).

- Osservatorio Nazionale del Turismo, 2018. Statistics. Available online: http://www.ontit.it/opencms/opencms/ont/it/statistiche/index.html (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- ISTAT. 2018. Available online: https://www.istat.it/ (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Direzione Sistema Statistico Regione Veneto, Turismo 2018. Available online: http://statistica.regione.veneto.it/banche_dati_economia_turismo.jsp (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- UNWTO. Compendium of Tourism Statistics Glossary. Available online: http://cf.cdn.unwto.org/sites/all/files/pdf/methodological_notes_2018.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Manente, M. Economia turistica regionale nel 2010. In Proceedings of the Atti dell’XI Conferenza Ciset, Venezia, Italy, 19 April 2011; Banca d’Italia: Venezia, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Manente, M. Oral presentation: Economia turistica regionale nel 2012. In Proceedings of the L’Italia e il Turismo Internazionale: Andamento Incoming e Outgoing nel 2012, Conference: CISET and Banca d’Italia, Venezia, Italy, 17 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Golja, T.; Krstinic Nizic, M. Corporate social responsibility in tourism—The most popular tourism destinations in Croatia: Comparative analysis. Manag. J. Contempor. Manag. Issues 2010, 15, 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Del Chiappa, G.; Grappi, S.; Romani, S. Attitudes toward responsible tourism and behavioral change to practice it: A demand-side perspective in the context of Italy. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 17, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Veneto Sistema Statistico Regionale 2015. Available online: http://statistica.regione.veneto.it/banche_dati_economia_turismo.jsp (accessed on 1 April 2018).

- Santeramo, F.B.; Seccia, A.; Nardone, G. The synergies of the Italian wine and tourism sectors. Wine Econ. Policy 2016, 6, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, E.; Perri, G. Food and Wine Tourism. Integrating Food, Travel and Terroir; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Charters, S.; Ali-Knight, J. Who is the wine tourists? Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L.; Cambourne, B.; Macionis, N. Wine Tourism around the World; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Mitchell, R. Wine tourism in the Mediterranean: A tool for restructuring and development. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2000, 42, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniface, P. Tasting Tourism: Travelling for Food and Drink; Ashgate: Burlington, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Wine, Food and Tourism Marketing; The Haworth Hospitality Press: Binghamton, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.G.; Eves, A.; Scarles, C. Building a model of local food consumption on trips and holidays: A grounded theory approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miles, S. The Western Front: Landscape, Tourism, and Heritage; Pen and Sword Books: Barnsley, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Terkenli, T.S. Landscape of Tourism: Towards a Global Cultural Economy of Space. Tour. Geogr. 2005, 4, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hare, D. Interpreting the Cultural Landscape for Tourism Development. Urban Des. Int. 1997, 2, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, D.C.; Michelle, M.; Metro-Roland, A.; Soper, K.; Greer, C.E. (Eds.) Landscape, Tourism, and Meaning; Ashgate Publishing: Burlington, VT, USA; Aldershot, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Daugstad, K. Negotiating landscape in rural tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 402–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B. What is Rural Tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznajder, M.; Przezbòrska, L.; Scrimgeour, F. Agritourism; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.; Prideaux, B.; McShane, C.; Dale, A.; Turnour, J.; Atkinson, M. Tourism development in agricultural landscapes: The case of the Atherton Tablelands, Australia. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briedenhann, J.; Wickens, E. Rural Tourism—Meeting the challenges of the New South Africa. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülcan, Y.; Kuştepeli, Y.; Akgüngör, S. Public Policies and Development of the Tourism Industry in the Aegean Region. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2009, 17, 1509–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B. Rural Tourism: An Overview. In The Sage Handbook of Tourist Studies; Jamal, T., Robinson, M., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2009; pp. 354–371. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrovski, D.; Todorovic, A.; Valjarevic, A. Rural Tourism and Regional Development: Case Study of Development of Rural Tourism in the Region of Gruţa, Serbia. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 14, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashper, K. Rural Tourism: An International Perspective; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E.; van Megen, K.; Buys, L. Impact and opportunities: Residents’ views on sustainable development tourism in regional Queensland, Australia. J. Tour. Chall. Trends 2010, 31, 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Tempesta, T.; Giancristofaro, R.; Corain, L.; Salmaso, L.; Tomasi, D.; Boatto, V. The importance of landscape in wine quality perception: An integrated approach using choice-based conjoint analysis and combination-based permutation tests. Food Qual. Perform. 2010, 21, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghello, S.; Manente, M. Dinamiche del Turismo in Provincia di Treviso. Focus Sulla Fruizione Enologica Nel Distretto Conegliano-Valdobbiadene; CIRVE: Padua, Italy, 2012; pp. 161–182. [Google Scholar]

- Mauracher, C.; Procidano, I.; Sacchi, G. Wine tourism quality perception and customer satisfaction reliability: The Italian Prosecco District. J. Wine Res. 2016, 27, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boatto, V.; Galletto, L.; Barisan, L.; Bianchin, F. The development of wine tourism in the Conegliano Valdobbiadene area. Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempesta, T.; Vecchiato, D.; Djumboung, D.A.; Chinazzi, G. An analysis of the potential effects of the modification of the Prosecco Protected Designation of Origin: A choice experiment. Int. Agric. Policy 2013, 2, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Manente, M.; Meneghello, S.; Mingotto, E. Dinamiche del turismo nel Distretto Conegliano-Valdobbiadene. Focus sulla fruizione enologica. In Distretto del Conegliano-Valdobbiadene. Rapporto Annuale 2017; CIRVE: Padua, Italy, 2017; Available online: http://www.prosecco.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/coneglianovaldobbiadene_rapporto-economico-2017.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2018).

- Annual Report of the Consorzio of Conegliano-Valdobbiadene 2014. Available online: http://www.prosecco.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/report_2014.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2018).

- Annual Report of the Consorzio of Conegliano-Valdobbiadene 2015. Available online: http://www.prosecco.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/2015-rapporto-4A.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2018).

- Annual Report of the Consorzio of Conegliano-Valdobbiadene 2016. Available online: http://www.prosecco.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/2016rapporto_annualeConeglianoValdobbiadene.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Annual Report of the Consorzio of Conegliano-Valdobbiadene 2017. Available online: http://www.prosecco.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/coneglianovaldobbiadene_rapporto-economico-2017.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- CIRVE. 2016. Available online: http://www.cirve.unipd.it/it/index.html (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Bourdeau, L.; Gravari-Barbas, M.; Robinson, M. (Eds.) World Heritage Sites and Tourism. Global and Local Relations; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Vallerani, F. Urban sprawl on the Venice mainland: Risks for the regional public heritage. Revista Movimentos Sociais e Dinâmicas Espaciais. 2012, 1, 130–147. [Google Scholar]

- La Tribuna di Treviso. Troppi Sbancamenti Sui Colli del Prosecco. 2018. Available online: http://tribunatreviso.gelocal.it/treviso/cronaca/2018/04/10/news/troppi-sbancamenti-sui-colli-del-prosecco-sos-dalla-marcia-stop-pesticidi-1.16695788 (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- La Tribuna di Treviso. Bosco Venduto e Abbattuto. <E ora pure avvelenato>. 2013. Available online: http://ricerca.gelocal.it/tribunatreviso/archivio/tribunatreviso/2013/05/11/NZ_39_01.html (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- De Nardi, C. Poisoned Prosecco Vineyards and the Downside of an Italian Icon: Analyses of Pesticides’ Impact on the Environment and Human Health. 2016. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjHo6O2vu7bAhWC7mEKHUmCBaoQFgglMAA&url=https%3A%2F%2Fandiamoavantitornandoindietro.jimdo.com%2Fapp%2Fdownload%2F10826016695%2FTesi%2BDe%2BNardi%2BCamilla%2B-%2BFinal%2BThesis%2BProject.pdf%3Ft%3D1482486345&usg=AOvVaw0mwfuWY1r-JuE6p_CxIwbl (accessed on 26 April 2018).

- The Telegraph. Wine War in Tuscany as Growers Warned that Vines Damage Environment. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/italy/11070631/Wine-war-in-Tuscany-as-growers-warned-that-vines-damage-environment.html (accessed on 28 April 2018).

- Löffler, R.; Walder, J.; Beismann, M.; Warmuth, W.; Steinicke, E. Amenity Migration in the Alps: Applying Models of Motivations and Effects to 2 Case Studies in Italy. Mt. Res. Dev. 2016, 36, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- La Tribuna di Treviso. Boschi Rasi al Suolo per il Prosecco Docg. Scoppia la Protesta. 2012. Available online: http://tribunatreviso.gelocal.it/treviso/cronaca/2012/05/01/news/boschi-rasi-al-suolo-per-il-prosecco-docg-scoppia-la-protesta-1.4449701 (accessed on 26 April 2018).

- Gliessman, S. Agroecology. The Ecology of Sustainable Food Systems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzaro, P.; Ferrarese, F.; Loddo, D.; Pappalardo, E.; Varotto, M. Mapping the Environmental Risk Potential on Surface Water of Pesticide Contamination in the Prosecco’s Vineyard Terraced Landscape. Presented at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly 2016, Vienna, Austria, 17–22 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Community. Directive on the Use of Sustainable Pesticides. 2009. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02009L0128-20091125&from=EN (accessed on 26 April 2018).

- Corriere del Veneto. Prosecco, Guerra Sui Limiti Anti-Pesticidi. 2017. Available online: http://corrieredelveneto.corriere.it/treviso/cronaca/17_dicembre_17/via-limiti-coltivazione-vignetiscatta-ricorso-tar-guerra-prosecco-7fb7a178-e3e6-11e7-a729-a41e0748ec41.shtml (accessed on 26 April 2018).

- The Sun. Prosecco in Bubble Trouble. Production of Brits’ Favourite Fizz Leaves Italian Villagers with Cancer after being Exposed to Dangerous Chemicals. 2016. Available online: https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/2267601/production-of-brits-favourite-fizz-prosecco-is-leaving-italians-with-with-cancer-and-exposed-to-dangerous-chemicals/ (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Visit Conegliano Valdobbiadene. Available online: http://www.prosecco.it/it/territorio/visit-conegliano-valdobbiadene/ (accessed on 12 April 2018).

- NOMISMA. Vino Bio: Nel 2015 in Crescita il Numero di Consumatori Italiani. 2015. Available online: http://www.nomisma.it/index.php/it/press-area/comunicati-stampa/item/823-20-marzo-2015-vino-bio-nel-2015-in-crescita-il-numero-di-consumatori-italiani/823-20-marzo-2015-vino-bio-nel-2015-in-crescita-il-numero-di-consumatori-italiani (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Storck, V.; Karpouzas, D.G.; Martin-Laurent, F. Towards a better pesticide policy for the European Union. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baedeker, K. Italie Septentrionale. Manuel du Voyageur; Baedeker: Leipzig, Germany, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Palladio, A. I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura; Franceschi: Venetia, Italy, 1570. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M. Rural; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schiratti, G. Invito Alla Strada del Vino Bianco: Conegliano—Valdobbiadene; Editrice Trevigiana: Treviso, Italy, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Sanson, L. La vite in collina. In Valdobbiadene fra Tradizione E Innovazione; Cierre Edizioni: Verona, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bitsani, E.; Kavoura, A. Connecting oenological and gastronomical tourisms at the Wine Roads, Veneto, Italy, for the promotion and development of agritourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2012, 18, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesi, R. Reinventare la campagna, a cominciare dal paesaggio. In Per una Nuova Urbanità. Dopo L’alluvione Immobiliarista; Bonora, P., Cervellati, P., Eds.; Diabasis: Reggio Emilia, Italy, 2009; pp. 190–213. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, R.S.; Cordano, M.; Silverman, M. Exploring individual and institutional drivers of proactive environmentalism in the US wine industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2005, 14, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.S.; Akoorie, M.E.M.; Hamann, R.; Sinha, P. Environmental practices in the wine industry: An empirical application of the theory of reasoned action and stakeholder theory in the United States and New Zealand. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, K.L.; Burritt, R.L. Critical environmental concerns in wine production: An integrative review. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 53, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.R. Integrated rural wine tourism: A case study approach. J. Wine Res. 2017, 28, 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, L.; Alonso, A.D.; Scherrer, P. Wine tourism as a development initiative in rural Canary Island communities. J. Enterp. Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2009, 3, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regolamento Comunale di Polizia Rurale 2018. Available online: http://www.cittadelvino.it/download.php?file=regolamento-intercomunale-di-polizia-rurale-prosecco_25.pdf. (accessed on 30 May 2018).

- Wine-Growing Protocol. Protocollo Vitivinicolo del Conegliano-Valdobbiadene Prosecco DOCG. 2018. Available online: http://www.prosecco.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Protocollo-2018-Pagine-Web.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention. CETS No. 176. 2000. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680080621 (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Nogué, J. El Observatorio del Paisaje de Catalunya. Rev. Geogr. Venez. 2010, 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Visentin, F. Gli osservatori del paesaggio tra istituzionalizzazione e azione dal basso. Esperienze regionali a confronto. Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana 2012, 5, 823–838. [Google Scholar]

- Visentin, F. Area dynamics and social participation: From the European Landscape Convention to the Observatori del Paisatge de Catalunya. Revista Movimentos Sociais e Dinamicas Espaciais 2013, 2, 54–73. [Google Scholar]

| Italians | Foreign | Total Amount | Var. % on the Previous Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Arrivals | Overnight Stays | Arrivals | Overnight Stays | Arrivals | Overnight Stays | Arrivals | Overnight Stays |

| 2007 | 67.939 | 181.878 | 42.244 | 118.402 | 110.183 | 300.280 | +6.4% | −0.6% |

| 2008 | 68.616 | 170.488 | 43.356 | 109.037 | 111.972 | 279.525 | +1.6% | −6.9% |

| 2009 | 61.730 | 134.676 | 36.423 | 90.586 | 98.153 | 225.262 | −12.3% | −19.4% |

| 2010 | 72.245 | 160.867 | 40.256 | 103.358 | 112.501 | 264.225 | +14.6% | +17.3% |

| 2011 | 69.339 | 164.127 | 41.427 | 116.953 | 110.766 | 281.080 | −1.5% | +6.4% |

| 2012 | 64.811 | 145.019 | 42.854 | 110.381 | 107.665 | 255.400 | −2.8% | −9.1% |

| 2013 | 64.395 | 135.590 | 43.995 | 109.634 | 108.390 | 245.224 | +0.7% | −4.0% |

| 2014 | 69.374 | 141.146 | 48.157 | 116.265 | 117.531 | 257.411 | +8.4% | +5.0% |

| 2015 | 73.306 | 141.349 | 53.586 | 124.463 | 126.892 | 265.812 | +8.0% | +3.3% |

| 2016 | 76.782 | 159.409 | 58.244 | 139.730 | 135.026 | 299.139 | +6.4% | +12.5% |

| Facilities | 2007 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|

| Hotels | 37 | 36 |

| Extra-hotel facilities divided into: | 205 | 341 |

| Guesthouse and Flat | 76 | 194 |

| Agritourism | 45 | 61 |

| B&B | 78 | 79 |

| Camping | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 5 | 6 |

| Total | 242 | 377 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Visentin, F.; Vallerani, F. A Countryside to Sip: Venice Inland and the Prosecco’s Uneasy Relationship with Wine Tourism and Rural Exploitation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072195

Visentin F, Vallerani F. A Countryside to Sip: Venice Inland and the Prosecco’s Uneasy Relationship with Wine Tourism and Rural Exploitation. Sustainability. 2018; 10(7):2195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072195

Chicago/Turabian StyleVisentin, Francesco, and Francesco Vallerani. 2018. "A Countryside to Sip: Venice Inland and the Prosecco’s Uneasy Relationship with Wine Tourism and Rural Exploitation" Sustainability 10, no. 7: 2195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072195