Resilient Entrepreneurship among European Higher Education Graduates

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Entrepreneurial Resilience

2.1. Youth Entrepreneurship

2.2. Perspectives on Resilient Entrepreneurship

2.3. Factors Shaping Entrepreneurial Resilience

3. Data and Methods

4. Results

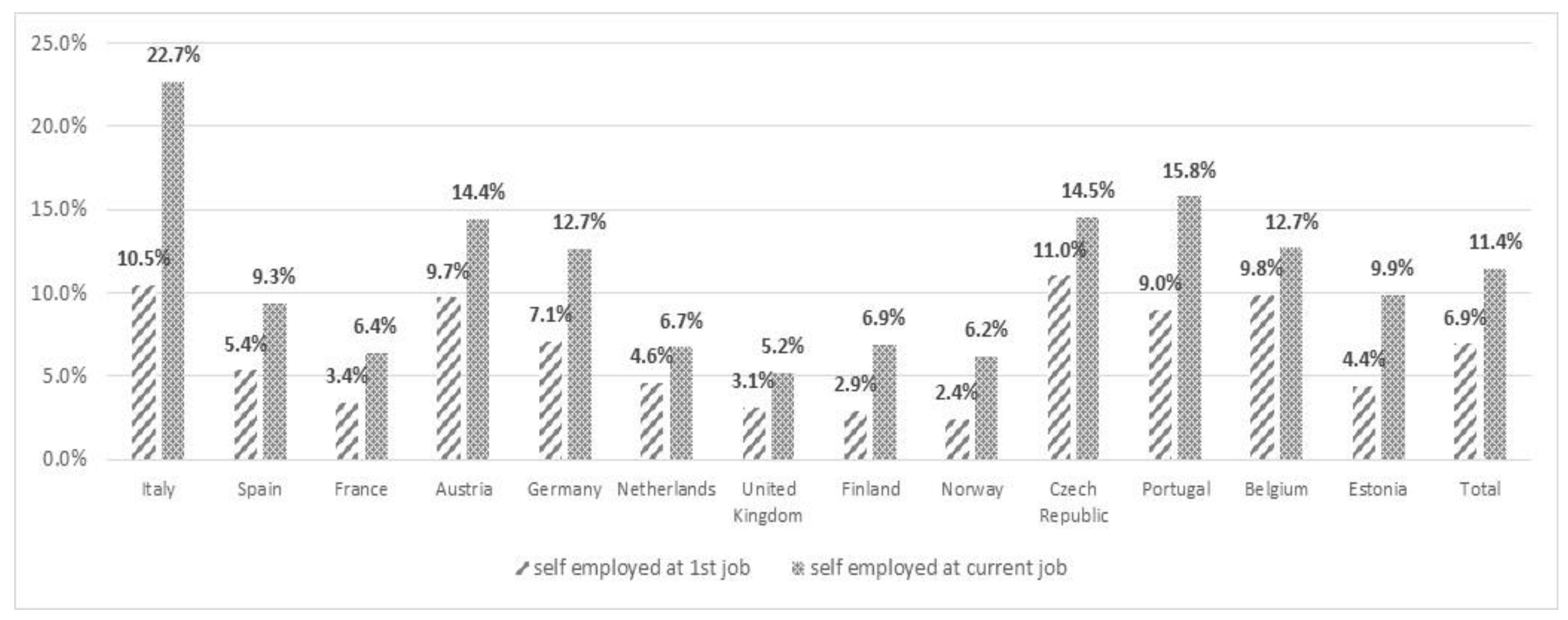

4.1. Incidence of Self-Employment among Higher Education Graduates

4.2. Profile of Higher Education Graduates Entering, Remaining and Returning in Self-Employment

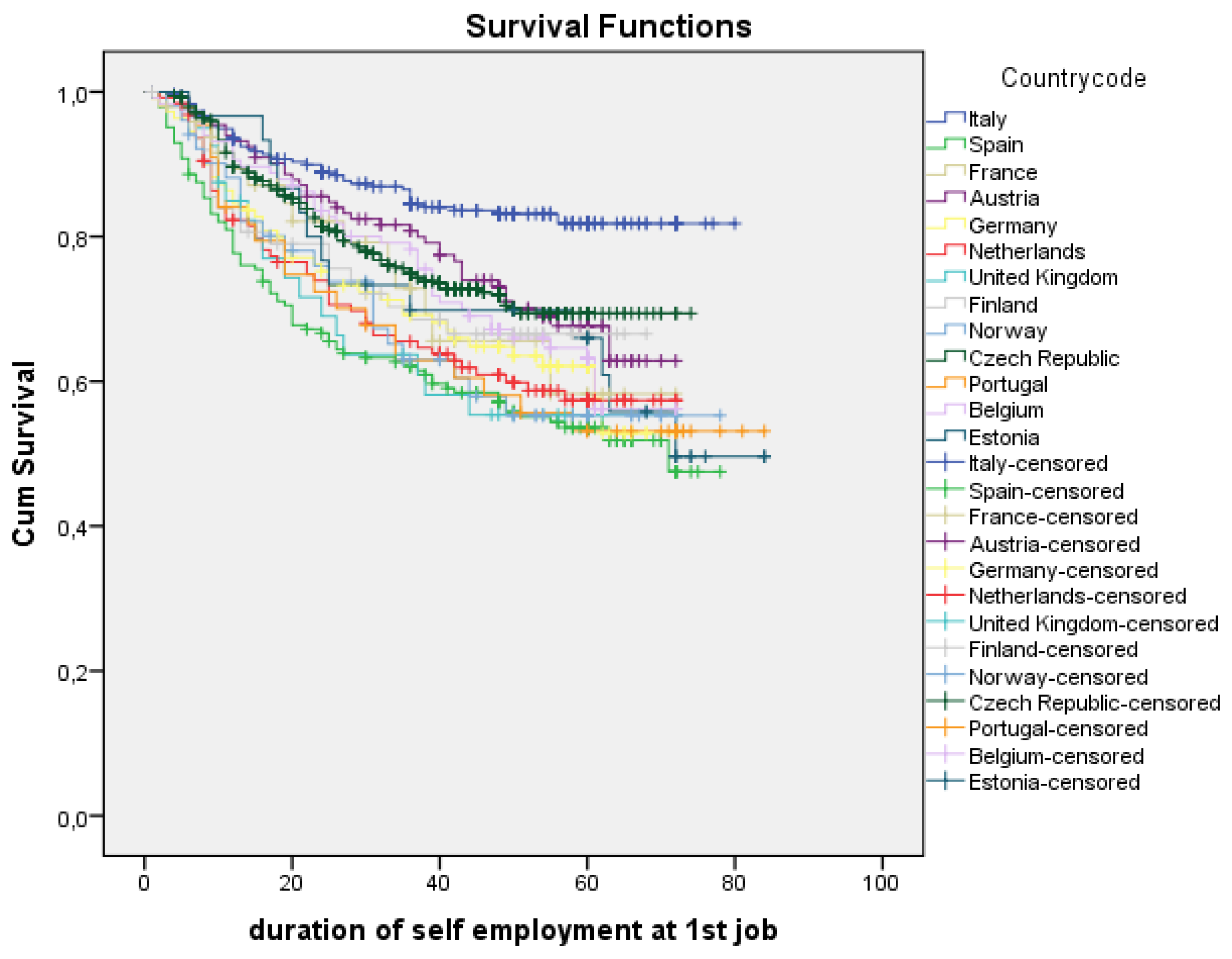

4.3. Factors Influencing Retention in Self-Employment

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables Label | Variable Group | Variable Type |

|---|---|---|

| Self-employed at first job | Dependent variable (M1) | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for being self-employed at first job after graduation and 0 for other situation |

| Remaining self-employed in current job | Dependent variable (M2) | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for being self-employed both at first job and current job (moment of the survey) and 0 for other situation |

| Returning to self-employment after leaving the first job | Dependent variable (M3) | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for being self-employed both at first job, leaving it and returning to self-employed at current job (moment of the survey) and 0 for other situation |

| Retention in self-employment at first job | Dependent variable (M4) | Continuous variable, number of months spent as self-employed in current job, calculated from the beginning of the first job till the end of it or till the moment of the survey |

| Country | Independent | Nominal variable, taking values from 1 to 17, according to country code (1 = Italy, 2 = Spain, 3 = France, 4 = Austria, 5 = Germany, 6 = Netherlands, 7 = United Kingdom, 8 = Finland, 10 = Norway, 11 = Czech Republic, 15 = Portugal, 16 = Belgium, 17 = Estonia) |

| Field of study (broad field) | Independent | Nominal variable, taking values from 1 to 8 (1 = Education, 2 = Humanities and arts, 3 = Social sciences, Business and Law, 4 = Science. Mathematics, Computing, 5 = Engineering, Manufacturing, Construction, 6 = Agriculture and Veterinary, 7 = Health and Welfare, 8 = Services) |

| Field of education and training | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for graduating a field of education and training related to environment protection and 0 for other situation |

| Grade compared to other students grades | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for graduating with a grade higher than average 0 for other situation |

| Situation in the last 1–2 years of study | Independent | Nominal variable, taking values from 1 for being fulltime student and 2 for being part-time student. All other values were treated as missing |

| Study program demanding | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for graduating a study program generally regarded as demanding (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very high extent) and 0 for other situation |

| Freedom in composing the own study program | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for graduating a study program generally regarded as providing freedom in organizing the study program (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very high extent) and 0 for other situation |

| Study program with a broad focus | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for graduating a study program generally regarded as having a broad focus (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very high extent) and 0 for other situation |

| Study program vocationally oriented | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for graduating a study program generally regarded as vocationally oriented (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very high extent) and 0 for other situation |

| Study program academically prestigious | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for graduating a study program generally regarded as academically prestigious (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very high extent) and 0 for other situation |

| Participation in research projects | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for graduating a study program where participation in research projects was used as teaching and learning method (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very high extent) and 0 for other situation |

| Project/problem-based learning | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for graduating a study program where project and/or problem-based learning was used as teaching and learning method (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very high extent) and 0 for other situation |

| Internship, work placement | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for graduating a study program where taking part to internships or different work placements was used as teaching and learning method (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very high extent) and 0 for other situation |

| Looking for work | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for having a job searching behavior prior or after graduation and 0 for nether searching for a job |

| Primary sector | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for working in agriculture, forestry, hunting, fishery and mining and quarrying and 0 for other situation |

| Secondary sector | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for working in industry and constructions and 0 for other situation |

| Tertiary sector | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for working in public or private services sectors and 0 for other situation |

| Need of training courses | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for working in a job needing initial formal training period and 0 for other situation |

| Need of informal learning | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for working in a job needing initial informal training period and 0 for other situation |

| Perceived under-education relative to study program | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for working undereducated in first job and 0 for other situation |

| Need for more knowledge and skills compared with what the individual posses | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for working in a job that demands more knowledge and skills that the graduate possess (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very high extent) and 0 for other situation |

| Usefulness of social network—Very useful | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for those considering social network (friends, relatives, colleagues, former teachers, etc.) as useful in setting up the business (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not very useful to 5 = very useful) and 0 for other situation |

| Very strong competition in the field | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for those considering the competition in the market they operate as strong and very strong (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = very weak to 5 = very strong) and 0 for other situation |

| Competition driven mainly by quality | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for those considering their organization as operating mainly by quality (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = mainly price to 5 = mainly quality) and 0 for other situation |

| Highly stable market | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for those considering the demand in the market they operate as stable and highly stable (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = highly stable to 5 = highly unstable) and 0 for other situation |

| Study program good basis for entrepreneurial skills | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for those considering their study program as a good basis for development of entrepreneurial skills (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = to a very high extent) and 0 for other situation |

| Work autonomy | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for those valuing work autonomy as a job characteristic (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = very important) and 0 for other situation |

| Opportunity to learn new things | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for those valuing opportunities to learn new things as a job characteristic (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = very important) and 0 for other situation |

| New challenges | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for those valuing new challenges as a job characteristic (values 4 and 5 on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = very important) and 0 for other situation |

| Gender | Independent | Nominal variable, taking value 1 for male and 2 for female. All other values were treated as missing |

| Age | Independent | Continuous variable, number of years at the moment of the survey |

| Father with higher education | Independent | Dummy variable, taking value 1 for those mentioning their father’s level of education being ISCED 5 + 6 and 0 for other situation |

| Country | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Italy | 14.9 | 20.2 | 6.7 |

| Spain | 9.5 | 7.7 | 12.2 |

| France | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.1 |

| Austria | 8.0 | 7.4 | 6.7 |

| Germany | 5.5 | 5.5 | 3.7 |

| Netherlands | 7.2 | 6.4 | 7.0 |

| United Kingdom | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.5 |

| Finland | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.1 |

| Norway | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.8 |

| Czech Republic | 33.9 | 32.9 | 43.4 |

| Portugal | 2.6 | 2.0 | 3.4 |

| Belgium | 5.7 | 5.9 | 5.5 |

| Estonia | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.8 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Field of Study (Broad Field) | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Education | 12.4 | 11.3 | 15.0 |

| Humanities and Arts | 15.1 | 15.4 | 13.1 |

| Social sciences, Business and Law | 29.0 | 30.1 | 22.9 |

| Science, Mathematics and Computing | 5.7 | 5.0 | 4.6 |

| Engineering, Manufacturing and Construction | 18.2 | 19.0 | 19.6 |

| Agriculture and Veterinary | 4.7 | 5.1 | 3.4 |

| Health and Welfare | 11.3 | 10.8 | 14.4 |

| Services | 2.4 | 2.1 | 4.6 |

| DNA | 1.3 | 1.3 | 2.4 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Situation in the Last 1–2 Years of Study | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Fulltime student | 67.2 | 66.6 | 65.7 |

| Part-time student | 32.1 | 32.9 | 32.7 |

| No answer | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Description of Study Program | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Perceived as demanding | 60.0 | 63.0 | 59.9 |

| Perceived as academically prestigious | 38.3 | 40.1 | 40.1 |

| Description of Methods of Teaching and Learning Used | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Project/problem-based learning | 26.7 | 28.0 | 27.5 |

| Participation to research projects | 41.7 | 40.6 | 47.1 |

| Job Searching Behavior | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Looked for a job | 44.7 | 39.5 | 52.3 |

| Never looked for a job | 55.3 | 60.5 | 47.7 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Main Economic Sector of Activity | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Primary sector | 3.3 | 3.8 | 1.8 |

| Secondary sector | 11.7 | 11.4 | 12.8 |

| Tertiary sector | 75.9 | 75.8 | 77.4 |

| Need for Initial Training | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Need of training courses | 12.4 | 13.4 | 9.8 |

| Need of informal learning | 26.2 | 24.4 | 29.7 |

| Under-Education at First Job | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Relative to study program | 9.7 | 11.5 | 9.2 |

| Need for more knowledge and skills | 30.6 | 32.1 | 30.6 |

| Usefulness of Social Network | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Useful and very useful | 42.3 | 44.2 | 44.6 |

| Other situation | 57.7 | 55.8 | 55.4 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Economic Context | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Very strong competition | 57.9 | 63.0 | 64.2 |

| Competition driven by quality | 43.0 | 46.9 | 47.4 |

| Highly stable market | 30.0 | 28.9 | 38.5 |

| Usefulness of Study Program for Entrepreneurial Skills | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Useful and very useful | 7.4 | 7.9 | 8.9 |

| Other situation | 92.6 | 92.1 | 91.1 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Valuing Job Characteristics | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Work autonomy | 54.7 | 56.5 | 62.1 |

| Opportunity to learn new things | 51.1 | 47.8 | 60.9 |

| New challenges | 36.6 | 34.1 | 45.6 |

| Gender | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Male | 44.3 | 48.4 | 43.7 |

| Female | 52.7 | 48.3 | 53.5 |

| DNA | 3.0 | 3.3 | 2.8 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Father’s Level of Education | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Having higher education or more | 31.0 | 31.0 | 32.7 |

| Having less that higher education | 69.0 | 69.0 | 67.3 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Age | Total Number of Self-Employed at First Job | Total Number of Those Remaining Self-Employed in Current Job | Total Number of Those Returning to Self-Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2209 | N = 1321 | N = 327 | |

| Valid values | 2125 | 1263 | 315 |

| Mean | 32.21 | 32.84 | 31.37 |

| Median | 30.00 | 31.00 | 30.00 |

References

- Neenan, M. Developing Resilience; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781351745338. [Google Scholar]

- Zautra, A.J.; Hall, J.S.; Murray, K.E. Resilience: A New Definition of Health for People and Communities. In Handbook of Adult Resilience; Reich, J.W., Zautra, A.J., Hall, J.S., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 3–30. ISBN 978-1-60623-488-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. Developing Concepts in Developmental Psychopathology. In Developmental Psychopathology and Wellness: Genetic and Environmental Influences; Hudziak, J.J., Ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 3–22. ISBN 978-1585622795. [Google Scholar]

- Hedner, T.; Abouzeedan, A.; Klofsten, M. Entrepreneurial resilience. Ann. Innov. Entrep. 2011, 2, 7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Resilience in Individual Development: Successful Adaptation Despite Risk and Adversity. In Risk and Resilience in Inner City America: Challenges and Prospects; Wang, M., Gordon, E., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associated: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 3–27. ISBN 978-0805813258. [Google Scholar]

- Bigos, M.; Qaran, W.; Fenger, M.; Koster, F.; Mascini, P.; van der Veen, R. Review Essay on Labour Market Resilience. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Menno_Fenger/publication/258568715_Review_Essay_on_Labour_Market_Resilience/links/00b49528b2fe842f5e000000/Review-Essay-on-Labour-Market-Resilience.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2018).

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Breen, P.; Anderies, J.M. Resilience: A Literature Review. Background Paper, Bellagio Initiative; IDS: Brighton, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Linking Sociological and Ecological Systems for Resilience and Sustainability. In Linking Sociological and Ecological Systems: Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience; Berkes, F., Folke, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 1–25. ISBN 9780521785624. [Google Scholar]

- Simmie, J.; Martin, R.L. The economic resilience of regions: Towards an evolutionary approach. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendell, R.; Foster, K.A.; Cowell, M. Resilience and Regions: Building Understanding of the Metaphor. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, R. Regional Resilience: A promising Concept to Explain Differences in Regional Economic Adaptability? Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; Dawley, S.; Tomaney, J. Resilience, Adaptation and Adaptability. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, H.; Boylan, M.; Martin, R. Early Career Resilience: Interdisciplinary Insights to Support Professional Education of Radiation Therapists. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2014, 45, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.; Down, B.; Le Cornu, R.; Peters, J.; Sullivan, A.; Pearce, J.; Hunter, J. Promoting early career teacher resilience: A framework for understanding and acting. Teach. Teach. 2014, 20, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, C.; von Treuer, K.; Koh, C. Resilience in early-career psychologists. Aust. Psychol. 2017, 52, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.; Down, B.; Le Cornu, R.; Peters, J.; Sullivan, A.; Pearce, J.; Hunter, J. Early Career Teachers. Stories of Resilience; Springer: Singapore, 2015; ISBN 978-981-287-173-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Tao, H.; Bowers, B.J.; Brown, R.; Zhang, Y. Influence of Social Support and Self-Efficacy on Resilience of Early Career Registered Nurses. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 40, 648–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, C.; Beltman, S.; Price, A. ‘I’m coming back again!’ The resilience process of early career teachers. Teach. Teach. 2014, 20, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strat, V.A.; Davidescu, A.A.M.; Grosu, R.M.; Zgură, I.D. Regional Development Fueled by Entrepreneurial Ventures Providing KIBS—Case Study on Romania. Amfiteatru Econ. 2016, 18, 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque, M.; Minniti, M. The effect of aging on entrepreneurial behavior. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, N.; Levie, J. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2009—Executive Report. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. 2010. Available online: https://www.babson.edu/Academics/centers/blank-center/global-research/gem/Documents/gem-2009-global-report.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Minola, T.; Criaco, G.; Cassia, L. Are youth really different? New beliefs for old practices in entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2014, 18, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvouletý, O.; Mühlböck, M.; Warmuth, J.; Kittel, B. ‘Scarred’ young entrepreneurs. Exploring young adults’ transition from former unemployment to self-employment. J. Youth Stud. 2018, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Luoto, S.; Tornikoski, E.T. Influence of work history on entrepreneurial intentions in ‘prime age’ and ‘third age’: A preliminary study. Int. Small Bus. J. 2010, 28, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoof, U. Stimulating Youth Entrepreneurship: Barriers and Incentives to Enterprise Start-Ups by Young People; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Available online: http://www.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/2006/106B09_94_engl.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2018).

- Minola, T.; Giorgino, M. Who’s going to provide the funding for high tech start-ups? A model for the analysis of determinants with a fuzzy approach. R & D Manag. 2008, 38, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M.; Congregado, E.; Golpe, A.A.; Iglesias, J. Self-employment and Business Cycles: Searching for Asymmetries in a Panel of 23 OECD Countries. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 17, 1155–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvouletý, O. Does the Self-employment Policy Reduce Unemployment and Increase Employment? Empirical Evidence from the Czech Regions. Cent. Eur. J. Public Policy 2017, 11, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arulampalam, W.; Gregg, P.; Gregory, M. Introduction: Unemployment Scarring. Econ. J. 2001, 111, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilam-Shamir, G.; Yaakobi, E. Effects of Early Employment Experiences on Anticipated Psychological Contracts. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røed, K.; Skogstrøm, J.F. Job Loss and Entrepreneurship. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2014, 76, 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, K.; Pathak, S.; Autio, E. How Culture Moulds the Effects of Self-efficacy and Fear of Failure on Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2013, 25, 756–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Martinez, M.A. Many are called, but few are chosen: An evolutionary perspective for the study of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2001, 25, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maer Matei, M.M.; Lungu, E. What determines you to be an entrepreneur? SEA–Pract. Appl. Sci. 2014, 2, 310–318. [Google Scholar]

- Sheffi, Y. The Resilient Enterprise: Overcoming Vulnerability for Competitive Enterprise; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; ISBN 9780262195379. [Google Scholar]

- Fiksel, J. Sustainability and resilience: Toward a systems approach. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2006, 2, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, M.-J.; Barbosa, S.D. Resilience and entrepreneurship: A dynamic and biographical approach to the entrepreneurial act. Management 2016, 19, 89–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, J.-C.; Manzano, G. The resilience of the entrepreneur. Influence on the success of the business. A longitudinal analysis. J. Econ. Psychol. 2014, 42, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, A.; Renko, M.; Myatt, T. Danger zone entrepreneurs: The importance of resilience and self-efficacy for entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 473–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnis-Bowers, C.; Parris, D.L.; Galperin, B.L. Which came first, the chicken or the egg? Exploring the relationship between entrepreneurship and resilience among the Boruca Indians of Costa Rica. JEC 2017, 11, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J. Entrepreneurial Failures: Key Challenges and Future Directions. In Entrepreneurship: The Way Ahead; Welsch, H.P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 133–150. ISBN 0-415-32394-0. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, P.D.; Singh, S.; Pavlovich, K. Entrepreneurial resilience and venture failure. ISBJ 2017, 35, 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, J. Entrepreneurial learning from failure: An interpretive phenomenological analysis. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 604–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DeTienne, D.R.; McKelvie, A.; Chandler, G.N. Making sense of entrepreneurial exit strategies: A typology and test. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tienne, D.R.; Wennberg, K. Studying exit from entrepreneurship: New directions and insights. ISBJ 2016, 34, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bates, T. Analysis of young, small firms that have closed: Delineating successful from unsuccessful closures. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headd, B. Redefining business success: Distinguishing between closure and failure. Small Bus. Econ. 2003, 21, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, A. Death is not a success: Reflections on business exit. ISBJ 2014, 32, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefis, E.; Marsili, O. Survivor: The role of innovation in firms’ survival. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coad, A.; Frankish, J.; Roberts, R. Growth paths and survival chances: An application of gambler’s ruin theory. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, M.; Milestad, R.; Hahn, T.; von Oelreich, J. The Resilience of a Sustainability Entrepreneur in the Swedish Food System. Sustainability 2016, 8, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber, S.; McNaughton, R.B. Resilience and entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar Jahanshahi, A.; Brem, A.; Shahabinezhad, M. Does Thinking Style Make a Difference in Environmental Perception and Orientation? Evidence from Entrepreneurs in Post-Sanction Iran. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghența, M.; Matei, A. SMEs and the Circular Economy: From Policy to Difficulties Encountered During Implementation. Amfiteatru Econ. 2018, 20, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.J. Affective style, psychopathology and resilience: Brain mechanisms and plasticity. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 1196–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leadbeater, B.; Dodgen, D.; Solarz, A. The Resilience Revolution: A Paradigm Shift for Research and Policy. In Resilience in Children, Families, and Communities: Linking Context to Practice and Policy; Peters, R.D., Leadbeater, B., McMahon, R.J., Eds.; Kluwer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 47–61. ISBN 978-0-306-48655-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, J.M.; Vanepps, E.M.; Hayes, A.F. The moderating role of social ties on entrepreneurs’ depressed affect and withdrawal intentions in response to economic stress. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullougha, A.; Renko, M. Entrepreneurial resilience during challenging times. Bus. Horiz. 2013, 56, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.R.; Frese, M.; Baron, R.A. The Psychology of Entrepreneurship; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 9780805850628. [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun, A.; Ibrahim, M.D.; Yusoff, M.N.; Fazal, S.A. Entrepreneurial Leadership, Performance, and Sustainability of Micro-Enterprises in Malaysia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Danes, S.M. Resiliency and resilience process of entrepreneurs in new venture creation. Entrep. Res. J. 2015, 5, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windapo, A. Entrepreneurial Factors Affecting the Sustainable Growth and Success of a South African Construction Company. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchek, S. Entrepreneurial resilience: A biographical analysis of successful entrepreneurs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, T. Entrepreneur human capital inputs and small business longevity. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1990, 72, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, K.; Wiklund, J.; Detienne, D.R. Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial exit: Divergent exit routes and their drivers. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterbeek, H.; Van Praag, M.; Ijsselstein, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2010, 54, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Hashim, N. Impact of Entrepreneurial Education on Entrepreneurial Intentions of Pakistani Students. J. Entrep. Bus. Innov. 2015, 2, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirciog, S.; Ciuca, V.; Popescu, M.E. The Net Impact of Training Measures from Active Labour Market Programs in Romania—Subjective and Objective Evaluation. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 26, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. ASQ 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J. Entrepreneurship and economic development: The valley of backwardness. Ann. Innov. Entrep. 2010, 1, 5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmash, B. Entrepreneurial Resilience: Locus of Control and Well-being of Entrepreneurs. J. Entrep. Organ. Manag. 2016, 5, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, G.D.; Baron, R.A. Person-entrepreneurship fit: Why some people are more successful as entrepreneurs than others. HRMR 2003, 13, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, G.H.; Sima, V.; Nica, E.; Gheorghe, I.G. Measuring Sustainable Competitiveness in Contemporary Economies—Insights from European Economy. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M. Market Imperfections, Opportunity and Sustainable Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.; Sandner, P. Necessity and Opportunity Entrepreneurs and Their Duration in Self-employment: Evidence from German Micro Data. J. Ind. Compet. Trade 2009, 9, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cox, D.R. Regression Models and Life-Tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1972, 34, 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, D.N. By choice and by necessity: Entrepreneurship and self-employment in the developing world. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2014, 26, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.H.; Kohn, K.; Miller, D.; Ullrich, K. Necessity entrepreneurship and competitive strategy. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 44, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, S.; Militaru, E. Interactions between policy effects, population characteristics and the tax-benefit system: An illustration using child poverty and child related policies in Romania and the Czech Republic. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 128, 1365–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Personal Characteristics | Education Background | Business Environment | Education-Job Match |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Current Job (Moment of the Survey) | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Employed | Other Occ. Status | No Paid Work | No Answer | |||

| First job after graduation | Self-employed | 64.0 | 27.3 | 7.5 | 1.3 | 100.0 |

| Other occupational status | 5.8 | 84.7 | 8.1 | 1.3 | 100.0 | |

| Had paid work before graduation | 14.8 | 84.7 | 0.5 | 100.0 | ||

| No paid work | 0.2 | 2.1 | 95.2 | 2.4 | 100.0 | |

| No answer | 6.7 | 50.1 | 9.0 | 34.2 | 100.0 | |

| Variables | M1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | Sig. | Exp (B) | |

| Country (Estonia—reference) | ||||

| Italy | 1.120 | 0.179 | 0.000 | 3.066 |

| Spain | 0.726 | 0.185 | 0.000 | 2.066 |

| France | 0.219 | 0.219 | 0.317 | 1.245 |

| Austria | 0.862 | 0.188 | 0.000 | 2.367 |

| Germany | 0.553 | 0.194 | 0.004 | 1.738 |

| Netherlands | 0.215 | 0.186 | 0.248 | 1.240 |

| United Kingdom | −0.146 | 0.227 | 0.520 | 0.864 |

| Finland | −0.368 | 0.204 | 0.071 | 0.692 |

| Norway | −0.527 | 0.222 | 0.018 | 0.590 |

| Czech Republic | 1.367 | 0.171 | 0.000 | 3.925 |

| Portugal | 0.737 | 0.221 | 0.001 | 2.089 |

| Belgium | 1.243 | 0.192 | 0.000 | 3.467 |

| Field of study (Education—reference) | ||||

| Humanities and arts | 0.484 | 0.096 | 0.000 | 1.623 |

| Social sciences, Business and Law | −0.147 | 0.085 | 0.083 | 0.863 |

| Science. Mathematics, Computing | −0.557 | 0.124 | 0.000 | 0.573 |

| Engineering, Manufacturing, Construction | −0.069 | 0.099 | 0.488 | 0.934 |

| Agriculture and Veterinary | 0.320 | 0.147 | 0.029 | 1.377 |

| Health and Welfare | −0.085 | 0.100 | 0.396 | 0.919 |

| Services | 0.088 | 0.165 | 0.593 | 1.092 |

| Situation in the last 1–2 years of study (Part-time student—reference) | ||||

| Full-time student | −0.141 | 0.061 | 0.020 | 0.868 |

| Description of study program (not perceived as such—reference) | ||||

| Study program demanding | 0.158 | 0.051 | 0.002 | 1.172 |

| Methods of teaching and learning (Low extent of project/problem-based learning—reference) | ||||

| Project/problem-based learning | 0.208 | 0.056 | 0.000 | 1.231 |

| Job searching behavior (not looking for work—reference) | ||||

| Looking for work | −0.515 | 0.053 | 0.000 | 0.597 |

| Economic sector (any other—reference) | ||||

| Primary sector | 1.510 | 0.174 | 0.000 | 4.528 |

| Secondary sector | 0.623 | 0.112 | 0.000 | 1.865 |

| Tertiary sector | 1.025 | 0.089 | 0.000 | 2.787 |

| Job needing initial training period (any other—reference) | ||||

| Need of training courses | −0.230 | 0.072 | 0.002 | 0.795 |

| Need of informal learning | −0.219 | 0.056 | 0.000 | 0.804 |

| Under-education at first job (not mentioned—reference) | ||||

| Perceived under-education relative to study program | 0.250 | 0.083 | 0.003 | 1.283 |

| Need for more knowledge and skills compared with what the individual posses | 0.281 | 0.053 | 0.000 | 1.324 |

| Usefulness of social network (not or low usefulness—reference) | ||||

| Very useful | 0.381 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 1.464 |

| Economic context (not mentioned—reference) | ||||

| Very strong competition in the field | 0.389 | 0.053 | 0.000 | 1.476 |

| Competition driven mainly by quality | 0.186 | 0.051 | 0.000 | 1.204 |

| Highly stable market | −0.165 | 0.054 | 0.002 | 0.848 |

| Study program useful for development of entrepreneurial skills (not or low extent—reference) | ||||

| Study program good basis for entrepreneurial skills | −0.279 | 0.060 | 0.000 | 0.757 |

| Job characteristics valued by respondents (no or low importance—reference) | ||||

| Work autonomy | 0.219 | 0.071 | 0.002 | 1.245 |

| Opportunity to learn new things | −0.326 | 0.073 | 0.000 | 0.722 |

| Gender (female—reference) | ||||

| Male | 0.159 | 0.052 | 0.002 | 1.173 |

| Age | 0.038 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 1.039 |

| Family background (father with upmost medium education—reference) | ||||

| Father with high education | 0.137 | 0.055 | 0.013 | 1.147 |

| Constant | −5.305 | 0.275 | 0.000 | 0.005 |

| M2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | Sig. | Exp (B) | |

| Country (Estonia—reference) | ||||

| Italy | 1.305 | 0.359 | 0.000 | 3.687 |

| Spain | 0.137 | 0.359 | 0.703 | 1.146 |

| France | 0.915 | 0.448 | 0.041 | 2.497 |

| Austria | 0.079 | 0.367 | 0.829 | 1.082 |

| Germany | 0.203 | 0.381 | 0.595 | 1.225 |

| Netherlands | 0.180 | 0.371 | 0.628 | 1.197 |

| United Kingdom | −0.200 | 0.454 | 0.659 | 0.819 |

| Finland | 0.333 | 0.407 | 0.413 | 1.396 |

| Norway | 0.214 | 0.443 | 0.630 | 1.238 |

| Czech Republic | 0.513 | 0.335 | 0.126 | 1.670 |

| Portugal | −0.268 | 0.435 | 0.537 | 0.765 |

| Belgium | 0.625 | 0.379 | 0.099 | 1.869 |

| Description of study program (not perceived as such—reference) | ||||

| Study program demanding | 0.201 | 0.099 | 0.042 | 1.222 |

| Economic sector (any other—reference) | ||||

| Primary sector | 0.477 | 0.280 | 0.088 | 1.611 |

| Under-education at first job (not mentioned—reference) | ||||

| Perceived under-education relative to study program | 0.510 | 0.173 | 0.003 | 1.666 |

| Need for more knowledge and skills compared with what the individual posses | 0.231 | 0.105 | 0.028 | 1.260 |

| Economic context (not mentioned—reference) | ||||

| Very strong competition in the field | 0.477 | 0.101 | 0.000 | 1.611 |

| Competition driven mainly by quality | 0.369 | 0.103 | 0.000 | 1.447 |

| Highly stable market | −0.217 | 0.108 | 0.044 | 0.805 |

| Job characteristics valued by respondents (no or low importance—reference) | ||||

| Work autonomy | 0.256 | 0.145 | 0.079 | 1.291 |

| Opportunity to learn new things | −0.351 | 0.161 | 0.029 | 0.704 |

| New challenges | −0.287 | 0.127 | 0.024 | 0.751 |

| Gender (female—reference) | ||||

| Male | 0.347 | 0.097 | 0.000 | 1.414 |

| Age | 0.052 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 1.054 |

| Constant | −2.207 | 0.492 | 0.000 | 0.110 |

| Variables | M3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | Sig. | Exp (B) | |

| Field of study (Education—reference) | ||||

| Humanities and arts | −0.575 | 0.290 | 0.048 | 0.563 |

| Social sciences, Business and Law | −0.767 | 0.261 | 0.003 | 0.464 |

| Science. Mathematics, Computing | −1.020 | 0.395 | 0.010 | 0.361 |

| Engineering, Manufacturing, Construction | −0.325 | 0.286 | 0.256 | 0.723 |

| Agriculture and Veterinary | −0.711 | 0.448 | 0.112 | 0.491 |

| Health and Welfare | 0.129 | 0.295 | 0.661 | 1.138 |

| Services | 0.777 | 0.488 | 0.111 | 2.175 |

| Description of study program (not perceived as such—reference) | ||||

| Study program academically prestigious | 0.330 | 0.163 | 0.043 | 1.391 |

| Methods of teaching and learning (Low extent of project/problem-based learning—reference) | ||||

| Participation to research projects | 0.350 | 0.157 | 0.026 | 1.420 |

| Usefulness of social network (not or low usefulness—reference) | ||||

| Very useful | 0.285 | 0.158 | 0.072 | 1.330 |

| Economic context (not mentioned—reference) | ||||

| Very strong competition in the field | 0.828 | 0.165 | 0.000 | 2.288 |

| Competition driven mainly by quality | 0.395 | 0.164 | 0.016 | 1.484 |

| Study program useful for development of entrepreneurial skills (not or low extent—reference) | ||||

| Study program good basis for entrepreneurial skills | −0.527 | 0.191 | 0.006 | 0.590 |

| Gender (female—reference) | ||||

| Male | 0.400 | 0.170 | 0.019 | 1.492 |

| Constant | −0.927 | 0.298 | 0.002 | 0.396 |

| Variables | Model 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | Sig. | Exp (B) | |

| Country (Estonia—reference) | ||||

| Italy | −1.053 | 0.346 | 0.002 | 0.349 |

| Spain | −0.198 | 0.324 | 0.542 | 0.821 |

| France | −1.106 | 0.486 | 0.023 | 0.331 |

| Austria | −0.588 | 0.353 | 0.096 | 0.555 |

| Germany | −0.286 | 0.369 | 0.439 | 0.752 |

| Netherlands | −0.388 | 0.346 | 0.263 | 0.678 |

| United Kingdom | 0.267 | 0.405 | 0.510 | 1.306 |

| Finland | −0.225 | 0.399 | 0.573 | 0.799 |

| Norway | −0.188 | 0.394 | 0.634 | 0.829 |

| Czech Republic | −0.941 | 0.321 | 0.003 | 0.390 |

| Portugal | −0.428 | 0.394 | 0.277 | 0.652 |

| Belgium | −0.796 | 0.347 | 0.022 | 0.451 |

| Grades during study time (average and below—reference) | ||||

| Grades higher than the average | −0.193 | 0.108 | 0.075 | 0.825 |

| Situation in the last 1–2 years of study (Part-time student—reference) | ||||

| Full-time student | 0.643 | 0.152 | 0.000 | 1.902 |

| Methods of teaching and learning used: research projects (Low extent—reference) | ||||

| Participation to research projects (high extent) | −0.112 | 0.055 | 0.043 | 0.894 |

| Under-education at first job (not mentioned—reference) | ||||

| Perceived under-education relative to study program | −0.415 | 0.230 | 0.071 | 0.660 |

| Need for more knowledge and skills compared with what the individual posses | −0.201 | 0.045 | 0.000 | 0.818 |

| Study program useful for development of entrepreneurial skills (not or low extent—reference) | ||||

| Study program good basis for entrepreneurial skills | −0.123 | 0.046 | 0.007 | 0.884 |

| Economic sector (any other—reference) | ||||

| Secondary sector | 0.392 | 0.217 | 0.071 | 1.480 |

| Tertiary sector | 0.334 | 0.172 | 0.052 | 1.397 |

| Usefulness of social networkfor setting up own business (not or low usefulness—reference) | ||||

| Very useful | −0.071 | 0.040 | 0.073 | 0.931 |

| Job characteristics valued (no or low importance—reference) | ||||

| Opportunity to learn new things (high importance) | 0.181 | 0.088 | 0.040 | 1.198 |

| New challenges (high importance) | 0.161 | 0.074 | 0.030 | 1.174 |

| Gender (male—reference) | ||||

| Female | 0.272 | 0.109 | 0.013 | 1.313 |

| Age | −0.055 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.946 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zamfir, A.-M.; Mocanu, C.; Grigorescu, A. Resilient Entrepreneurship among European Higher Education Graduates. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082594

Zamfir A-M, Mocanu C, Grigorescu A. Resilient Entrepreneurship among European Higher Education Graduates. Sustainability. 2018; 10(8):2594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082594

Chicago/Turabian StyleZamfir, Ana-Maria, Cristina Mocanu, and Adriana Grigorescu. 2018. "Resilient Entrepreneurship among European Higher Education Graduates" Sustainability 10, no. 8: 2594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082594

APA StyleZamfir, A.-M., Mocanu, C., & Grigorescu, A. (2018). Resilient Entrepreneurship among European Higher Education Graduates. Sustainability, 10(8), 2594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082594