Assessing Livelihood Reconstruction in Resettlement Program for Disaster Prevention at Baihe County of China: Extension of the Impoverishment Risks and Reconstruction (IRR) Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Collapse of Original Livelihoods in Resettlement

2.2. Livelihood Assessment Model Overview

2.3. IRR Model Overview

- (1)

- Landlessness,

- (2)

- joblessness,

- (3)

- homelessness,

- (4)

- marginalization,

- (5)

- increased morbidity and mortality,

- (6)

- food insecurity,

- (7)

- loss of access to common property, and

- (8)

- social (community) disarticulation.

- (1)

- From landlessness to land-based resettlement,

- (2)

- from joblessness to reemployment,

- (3)

- from homelessness to house reconstruction,

- (4)

- from marginalization to social inclusion,

- (5)

- from increased morbidity to improved health care,

- (6)

- from food insecurity to adequate nutrition,

- (7)

- from loss of access to restoration of community assets and services, and

- (8)

- from social disarticulation to rebuilding networks and communities.

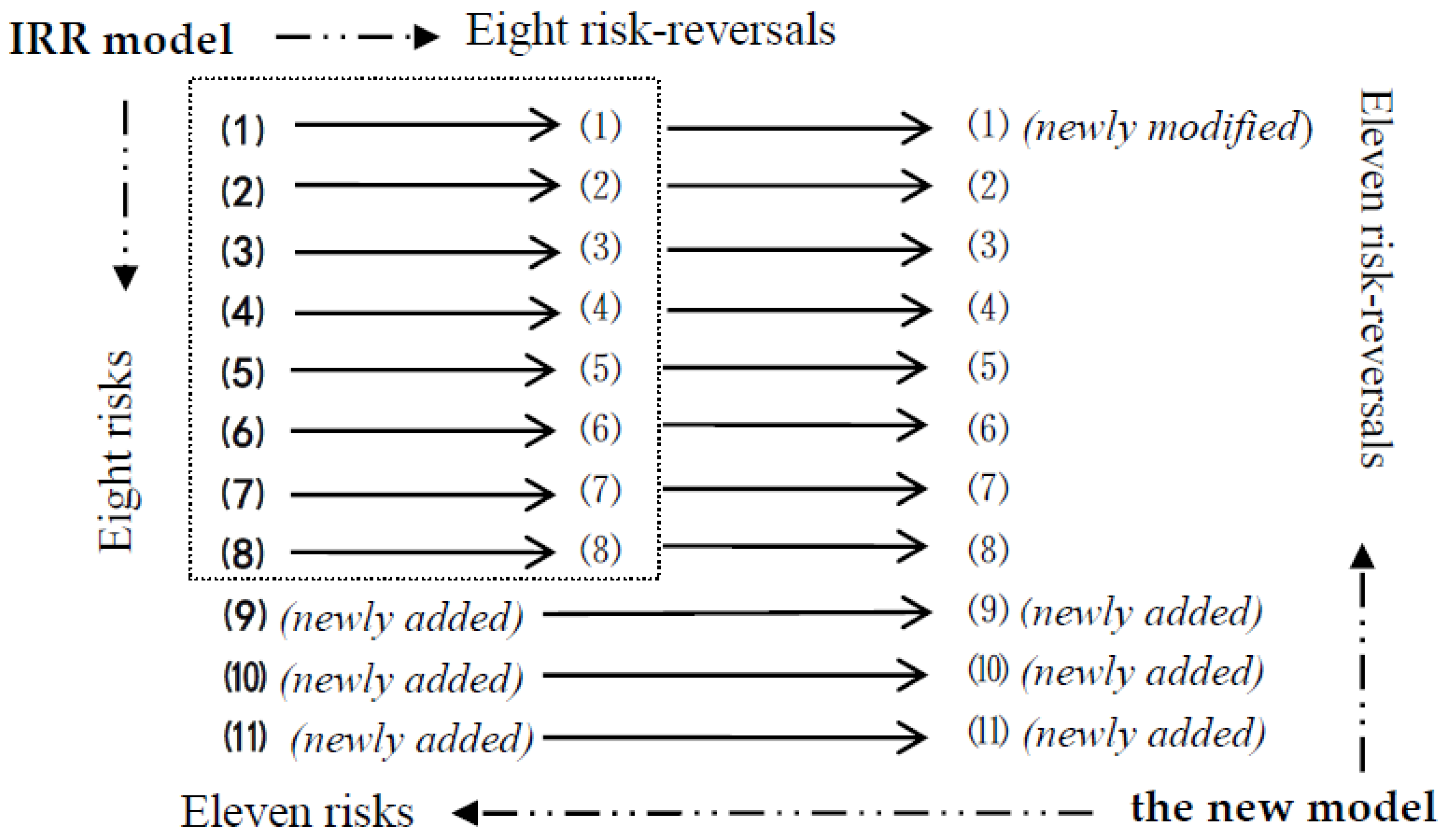

3. New Conceptual Framework and Its Indicators

3.1. Logical Schematic

3.2. The Conceptual Framework and the Indicators

- (1)

- From landless to income-based resettlement (newly modified). Farmland is an essential resource for farmers; therefore, land-based resettlement was highlighted for livelihood reconstruction of resettlers. In China, disaster-preventive resettlement is accompanied by urbanization; that is, most resettlements turn farmers into non-agricultural citizens by reducing their lands and providing alternative compensation in the form of money or houses. Land reduction does not necessarily mean worse living situations for resettlers, as their income is no longer determined by assets provided by natural resources, but mostly by revenues from non-farm activities [39,41]. Alternatively, agricultural activities that are more collective and cost-efficient than before can also increase the average agricultural income [8]. Income, no matter where it is from, is a major concern for resettled people [2], but it has been ignored in the IRR model. In other words, financial capital was not considered in the IRR Model. Thus, we replaced land-based resettlement with income-based resettlement, and two indicators, “savings change” and “income change”, were used and reported as X1 and X2, respectively, in Table 1.

- (2)

- From joblessness to reemployment. Two indicators, “employment chance” and “training chance”, were used and reported as X7 and X8, respectively.

- (3)

- From homelessness to house reconstruction. The indicator “housing condition” was used and reported as X9.

- (4)

- From marginalization to social inclusion. Two indicators, “relatives contacts” and “making friends”, were used and reported as X3 and X4, respectively.

- (5)

- From increased morbidity to improved health care. The indicator “disease incidence” was used and reported as X14.

- (6)

- From food insecurity to adequate nutrition. The indicator “food nutrition” was used and reported as X16.

- (7)

- From loss of access to restoration of community assets and services. Two indicators, “infrastructure condition” and “sanitation condition”, were used and reported as X5 and X6, respectively.

- (8)

- From social disarticulation to rebuilding networks and communities. Two indicators, “educational condition” and “community agency”, were used and reported as X11 and X12, respectively.

- (9)

- The feeling of disaster reduction (newly added). Disaster resettlement is different from development-forced displacement. Avoiding disaster was the most fundamental reason for disaster preventive displacement and resettlement. Thus, impacts of current and future disasters of the destination areas should be identified and assessed. If relocation sites are expected to experience increased or continued risk, then the effects of resettlement may be largely offset [10]. Thus we added an indicator “disaster reduction”, which was reported as X13.

- (10)

- The feeling of resettling performance (newly added). Successful resettlements require good public services, adequate funding, community development, authority responsibility, assessment, and involvement in decision-making [18]. Evaluation of satisfaction is an important way to assess the performance of livelihood reconstruction. The indicator “performance satisfaction” was used and reported as X10.

- (11)

- The feeling of public safety in relocating sites (newly added). Displacement and resettlement tend to bring social insecurity (disorder, conflict, or crime) [20], which may have negative effects on the livelihood reconstruction of resettlers [5,9]. A safe environment is another important guarantee for livelihood reconstruction. Therefore, we added the indicator “public safety” and report it as X15.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Household Survey

4.3. Statistical Methods

5. Test of the New Model

5.1. Reliability and Validity

5.2. Validity of the New Index System for Livelihood Reconstruction Assessment

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

6. Conclusions and Discussion

7. Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faas, A.J.; Jones, E.C.; Tobin, G.A.; Whiteford, L.M.; Murphy, A.D. Critical aspects of social networks in a resettlement setting. Dev. Pract. 2015, 25, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmsen, B.; Webber, M. What can we learn from the practice of development-forced displacement and resettlement for organised resettlements in response to climate change? Geoforum 2015, 58, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.; Muibi, K.H.; Alaga, A.T.; Babatimehin, O.; Ige-Olumide, O.; Mustapha, O.; Hafeez, S.A. Suitability analysis of resettlement sites for flood disaster victims in Lokoja and Environs. World Environ. 2015, 5, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, P.; Rahman, S.H.; Molla, M.H. Sustainable adaptation for resolving climate displacement issues of south eastern islands in Bangladesh. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Str. 2017, 9, 790–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manatunge, J.M.A.; Abeysinghe, U. Factors affecting the satisfaction of post-disaster resettlers in the long term: A case study on the resettlement sites of tsunami-affected communities in Sri Lanka. J. Asian Dev. 2017, 3, 94–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Sun, Y. Policy responses to disaster-induced migration in a changing climate-Adjustment of disaster-induced migration policies based on “regional conference on policy responses to climeate-induced migration in Asia and Pacific”. Adv. Earth Sci. 2012, 27, 573–580. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Kapucu, N. Examining the impacts of disaster resettlement from a livelihood perspective: A case study of Qinling Mountains, China. Disasters 2018, 42, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Li, S.; Feldman, M.W.; Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Daily, G.C. The impact on rural livelihoods and ecosystem services of a major relocation and settlement program: A case in Shaanxi China. Ambio 2018, 47, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Tan, Y.; Luo, Y. Post-disaster resettlement and livelihood vulnerability in rural China. Disast. Prev. Manag. 2017, 26, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M.M. Risks, safeguards and reconstruction: A model for population displacement and resettlement. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2000, 35, 3659–3678. [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, M.M.; McDowell, C. Risk and Reconstruction: Experiences of Resettlers and Refugees; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 11–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, M.M. IRR: An operational risks reduction model for population resettlement. Hydro Nepal: J. Water, Energ. Environ. 2007, 1, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M.M. The Risks and Reconstruction Model for Resettling Displaced Populations. World Dev. 2013, 25, 1569–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M.M. Concept and Method: Applying the IRR Model in Africa to Resettlement and Poverty, Displacement Risks in Africa; Kyoto University Press: Kyoto, Japan, 2005; pp. 195–239. [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, M.M.; Schmidt-Soltau, K. Poverty risks and national parks: Policy issues in conservation and resettlement. World Dev. 2006, 34, 1808–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggelund, G. Resettlement programmes and environmental capacity in the Three Gorges Dam Project. Dev. Change 2006, 37, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N. Putting ‘Relationships’ into the Impoverishment Risks and Reconstruction (IRR) Model: A Case Study of the Metro Manila Railway Project in the Philippines. Master’s Thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- de Sherbinin, A.; Castro, M.; Gemenne, F.; Cernea, M.M.; Adamo, S.; Fearnside, P.M.; Krieger, G.; Lahmani, S.; Oliver-Smith, A.; Pankhurst, A.; et al. Preparing for resettlement associate with climate change. Science 2011, 334, 456–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanclay, F. Project-induced displacement and resettlement: from impoverishment risks to an opportunity for development? Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.N.; Few, R. Social risks and challenges in post-disaster resettlement: the case of Lake Nyos Cameroon. J. Risk Res. 2012, 15, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Jones, L. Struggles over land, livelihood, and future possibilities: Reframing displacement through feminist political ecology. Signs 2018, 43, 711–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissell, R. Preparedness and Response for Catastrophic Disasters; The Chemical Rubber Company (CRC) Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Xue, F. Study on marginalization poverty in resettlement areas: Taking Danjiangkou reservoir area as an example. Learn. Pr. 2009, 10, 46–52. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kloos, H. Health aspects of resettlement in Ethiopia. Soc. Sci. Med. 1990, 30, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, M.; Salem-Murdock, M. Development-induced food insecurity in the middle senegal valley. GeoJournal 1993, 30, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Sattar, M.; Hossain, M.; Faisal, M.; Islam, R. An Internal Environmental Displacement and Livelihood Security in Uttar Bedkashi Union of Bangladesh. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2015, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toole, M. Mass population displacement: A global public health challenge. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 1995, 9, 353–366. [Google Scholar]

- The Department for International Development (DFID). Section 2. In Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; The Department for International Development: London, UK, 1999. Available online: https://www.ennonline.net/attachments/872/section2.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2018).

- Serrat, O. The sustainable livelihoods approach. In Knowledge Solutions; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, C.R.; Scholl, R. Structured mental model approach for analyzing perception of risks to rural livelihood in developing countries. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easdale, M.H.; Lopez, D.R. Sustainable livelihoods approach through the lens of the State-and-Transition Model in semi-arid pastoral systems. Rangel. J. 2016, 38, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Huang, X.; He, Y.; Yang, X. Assessment of livelihood vulnerability of land-lost farmers in urban fringes: A case study of Xi’an, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 59, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, M.B.; Riederer, A.M.; Foster, S.O. The livelihood vulnerability index: A pragmatic approach to assessing risks from climate variability and change—A case study in Mozambique. Glob. Environ. Change 2009, 19, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Wandel, J. Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edington, S. The inadequacy of the Risk Mitigation model for the restoration of livelihoods of displaced people. Case Study: The Cambodian Railway Rehabilitation Project. J. Arts Humanit. 2014, 3, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Advanced Training Program on Humanitarian Action (ATHA). Sustainable Livelihoods Framework. Available online: http://www.atha.se/content/sustainable-livelihoods-framework/ (accessed on 10 June 2018).

- Fan, M.M.; Li, Y.B.; Li, W.J. Solving one problem by creating a bigger one: The consequences of ecological resettlement for grassland restoration and poverty alleviation in Northwestern China. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmsen, B. Is land-based resettlement still appropriate for rural people in China? A longitudinal study of displacement at the Three Gorges Dam. Dev. Change 2018, 49, 170–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.; van Westen, A.; Zoomers, A. Compulsory land acquisition for urban expansion: Livelihood reconstruction after land loss in Hue’s peri-urban areas, Central Vietnam. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2017, 39, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xue, T. Reobserve disaster adapative resettlement project in southern Shaanxi Province. Outlook News week, June 2005; pp. 26–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Indicators | Measuring Items |

|---|---|

| X1 | Your savings are (will be) increased after the resettlements. |

| X2 | Your annual incomes are (will be) increased after resettlement. |

| X3 | New residence makes it more convenient for me to contact my relatives after resettlement. |

| X4 | New residence makes it easier for me to make new friends after resettlement. |

| X5 | After resettlement, the infrastructure (e.g., traffic conditions) becomes (will become) better. |

| X6 | After resettlement, drinking water and sanitation facilities become (will become) better (e.g., traffic conditions). |

| X7 | Companies in resettling sites are able to provide enough employment. |

| X8 | You can participate in knowledge and skill training provided by the government. |

| X9 | You are satisfied with the current compensation standard for house purchase. |

| X10 | You are satisfied with what the displacing and resettling agencies have done. |

| X11 | Management agencies in the resettling communities are perfect. |

| X12 | Educational conditions for children are (will be) improved after resettlement. |

| X13 | Loss caused by natural disasters (e.g., flood, geologic disaster) is (will be) reduced after the displacement. |

| X14 | Morbidity of resettlers is (will be) decreased after the displacement. |

| X15 | Public safety problems (e.g., theft, robbery) are (will be) reduced after the displacement. |

| X16 | Quality of your diet is (will be) improved after the displacement. |

| Variables | Having been Resettled (%) N = 305 (62.0) | To be Resettled (%) N = 187 (38.0) | Involved in Resettlement (%) N = 492 (100) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male (men) | 173 (56.7) | 127 (67.9) | 300 (61.0) |

| Age | Less than 18 years old | 6 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | 7 (1.4) |

| 18–45 years old | 252 (82.6) | 142 (75.9) | 394 (80.1) | |

| 46–60 years old | 44 (14.4) | 37 (19.8) | 81 (16.5) | |

| More than 60 years old | 3 (1.0) | 7 (3.7) | 10 (2.0) | |

| Education | Illiterate | 16 (5.2) | 21 (11.2) | 37 (7.5) |

| Elementary school | 128 (42.0) | 67 (35.8) | 195 (39.6) | |

| Junior middle school | 126 (41.3) | 58 (31.0) | 184 (37.4) | |

| Senior middle school and above | 35 (11.5) | 41 (21.9) | 76 (15.5) | |

| Annual income | 1000 and below (RMB) | 84 (27.5) | 27 (14.4) | 111 (22.6) |

| 1001–3000 | 125 (41.0) | 69 (36.9) | 194 (39.4) | |

| 3001–8000 | 73 (23.9) | 70 (37.5) | 143 (29.1) | |

| 8000 above | 23 (7.5) | 21 (11.2) | 44 (8.9) | |

| Conceptual Dimensions | Indicators and Measuring Items | Common Factors and Standard Loadings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life | Development | Safety | ||

| (1) (4) (7) | X1 | 0.724 | ||

| X2 | 0.647 | |||

| X3 | 0.745 | |||

| X4 | 0.773 | |||

| X5 | 0.722 | |||

| X6 | 0.678 | |||

| (2) (3) (8) (10) | X7 | 0.719 | ||

| X8 | 0.741 | |||

| X9 | 0.637 | |||

| X10 | 0.717 | |||

| X11 | 0.731 | |||

| X12 | 0.673 | |||

| (5) (6) (9) (11) | X13 | 0.768 | ||

| X14 | 0.768 | |||

| X15 | 0.714 | |||

| X16 | 0.616 | |||

| Cumulative variance explained | 22.24% | 44.19% | 60.26% | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, Q.; Liu, H.; Feldman, M. Assessing Livelihood Reconstruction in Resettlement Program for Disaster Prevention at Baihe County of China: Extension of the Impoverishment Risks and Reconstruction (IRR) Model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2913. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082913

Xiao Q, Liu H, Feldman M. Assessing Livelihood Reconstruction in Resettlement Program for Disaster Prevention at Baihe County of China: Extension of the Impoverishment Risks and Reconstruction (IRR) Model. Sustainability. 2018; 10(8):2913. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082913

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Qunying, Huijun Liu, and Marcus Feldman. 2018. "Assessing Livelihood Reconstruction in Resettlement Program for Disaster Prevention at Baihe County of China: Extension of the Impoverishment Risks and Reconstruction (IRR) Model" Sustainability 10, no. 8: 2913. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082913

APA StyleXiao, Q., Liu, H., & Feldman, M. (2018). Assessing Livelihood Reconstruction in Resettlement Program for Disaster Prevention at Baihe County of China: Extension of the Impoverishment Risks and Reconstruction (IRR) Model. Sustainability, 10(8), 2913. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082913