Abstract

The European Union’s (EU) remote rural areas undergo unique organizational challenges to counteract geopolitical, economic, and environmental constraints and engage in a competitive global food market. A one size fits all recipe to mend specific issues has also proven inefficient and led policy-makers to acknowledge the importance of implementing sustainable landscape governance to promote rural development. This paper inquires what are the challenges and opportunities food systems must adopt in a sustainable landscape governance approach, based on a qualitative research work carried out in the Azores Region (Portugal) in 2016. Data was gathered via eleven semi-structured interviews to key stakeholders and participatory observation in six events related to the management of the Azores’ food system. A grounded theory method structured qualitatively research participants’ perceptions about the Region’s food regime. This analysis is hereby furthered according to the four criteria proposed by the sustainable landscape governance assessment method. Our results indicate the lack of coordination among actors, institutions and policies in the Azores Region could be counteracted by promoting inclusive participation and integrated knowledge to attain cohesive, sustainable, and efficient outcomes at the landscape level. The methodology has proven to be adequate and instrumental in identifying sustainable landscape governance issues in other food systems.

1. Introduction

The centrality of governance issues in the discussion over the activities and processes determining food systems appears to escape the political agenda in less-prominent regions across Europe. A possible cause might be the disregard of “the complex set of interactions in multiple domains that are often not highlighted in conventional food chain analysis with a focus on food yields and flows” [1] (p. 32). The Outermost Regions of Europe (OR) [2] exemplify this situation and present think tanks situating these concerns mainly around the analysis of policy documents—namely, responding to agriculture and rural development policy frameworks. Little has been developed scientifically to adopt a systemic and multi-disciplinary approach to address management issues over food system processes in these regions [3,4]. This paper aims at filling in this gap by assessing food system governance in one of the OR, the Azores, from a sustainable landscape perspective.

Overcoming such a limitation requires the ability to attend to pressing issues on landscape governance and the sustainability of food systems in these regions. Debates today are based in localized research and policy analysis that examine critically—and transdisciplinary—specific contexts across the relevant scales and levels of the food system. To achieve this, food system assessments are thus required to recognize the singularity of these regions in the European context [5], prioritize a holistic, multi-level and multi-scale approach, and contemplate the need for hybrid national/regional frameworks in light of the EU cohesion policy and food-related policies. This approach is essential because food systems serve different ‘functions’ for different actors—who also value their outcomes differently—and similar outcomes cannot be expected in different landscapes [6].

The conceptual model of food systems discussed by Sobal (1998) shows the evolution of food systems thinking and points out the necessity to address food issues systemically, whether assumed in a chain, as a cycle, as a web, or within a specific context. The flow model introduced in the 1970s as the “food chain” assumes the sequence of steps involved in food processes. “Food cycles”, differently, move away from a linear perspective and evolves as a circular model that pays attention to feedback responses within the system, considering how objects and information link back across different scales and levels. In contrast, the network model is the “food web” and considers the interrelationships among diverse nodes in the operation and control of the food system. More recently, the ecological model framed by “food context” looks at the relationships of the food system with its environments, recognizing that they are also made up of many other systems [7] (p. 855).

Food system analysis today contemplate the four sets of activities and outcomes ranging from production through consumption pointed out by Ericksen (2008): food production, processing and packaging, distribution and retail, and consumption [6], in which a number of actors and relationships interact with the factors, interests and tensions at multiple levels and scales. Moreover, Ericksen stresses the need in recognizing the feedback loop of such activities—including the linkages among outcomes—to address the complexity of this research object, as “food systems produce outcomes that contribute to or detract from ecosystems and the services they provide, income for many people ranging from agricultural workers to retailers, and a host of other environmental and social welfare outcomes important to society” [6] (p. 13). For any holistic food system governance analysis in the twenty-first century, Ericksen (2010) emphasizes the need to accept that food systems encompass social, economic, ecological, and political issues, that are inherently cross-level and cross-scale [1] (p. 31).

The idea of sustainable landscapes gained popularity within the landscape management and sustainable landscape debates, leading to more specific and focused knowledge. In the last decade, these two research fields intertwined through the sustainable landscape governance approach to assess systems’ governance and discover what kind of policies, institutional arrangements, and governance mechanisms could facilitate a sustainable landscape (e.g., Southern et al., 2011) [8]. Particularly, Morangues-Faus et al. (2017) have introduced such approach in food systems analysis. They argue that food systems inform about the interactions between the social and ecological processes and resources occurring in landscapes, namely on the “complex multilevel networks of food actors and related activities, which are embedded in intricate socio-economic, political and ecological relationships that shape their outcomes across different geographies and social groups” [9] (p. 2).

This paper expands the scientific discussion about food systems, based on the qualitative, bottom-up analysis developed by Hernández (2016) in Terceira Island, Azores [10]. By examining what are the complex network of actors, factors, tensions, and processes that define the Azores’s food system and, thus, link food from the field to the table, we deploy the Manual for Assessing Landscape Governance (MALG) (2017) by the Green Livelihoods Alliance [11] to raise the fundamental issues on sustainable food systems governance in this Region.

The case study presented in this paper serves as an empirical contribution to the sustainable landscape governance debate. The paper embarks in a discussion about landscape governance issues, using the MALG as a guiding framework to evaluate the Autonomous Region of the Azores’ (ARA) food system. This exploration is highly relevant, not only as it furthers knowledge about sustainable governance; but also sheds light about issues affecting the food system of the studied region.

We explore whether the identified issues in ARA’s food system respond to the Azores’ condition as one of the Outermost Regions (OR) of Europe [2] and if they signal the need for EU cohesion policies and food-related policies—such as the EU Common Agricultural Policy—to consider the cross-fertilization of regional and national frameworks to adequately meet the needs of food systems at different levels.

This study is steered by the inquiry to identify what are the challenges and opportunities of sustainable food systems governance in the Azores. The paper is organized in six parts: first, we place this paper’s discussion in the broader theoretical context of food systems and sustainable landscape governance; second, we introduce the empirical case study; third, we describe the methodology used for the analysis hereby contemplated; fourth, we present the identified issues on the Azores’ food system following the four performance elements of inclusive and sustainable landscape governance by the Green Livelihoods Alliance (2017): (i) inclusive decision-making in the landscape; (ii) culture of collaboration in the landscape; (iii) coordination across landscape sectors, levels and actors; and (iv) sustainable landscape thinking and action; fifth, we discuss the results of our analysis in the framework of sustainable landscape governance, and last, we conclude stressing the instrumentality of using these four benchmarks to assess sustainable food systems governance.

2. Theoretical Scope

A sustainable landscape governance approach is deployed in this paper to thread the complex elements within ARA’s food system and unveil the current opportunities and challenges for the Region to govern it sustainably.

2.1. Sustainable Landscapes and Food Systems

Assessing food systems governance from a sustainable landscape perspective encourages us to first consider the complementary physical (e.g., land use, land resources, land management) and structural (i.e., the set of rules and norms that determine the spatial arrangement in a landscape) aspects that give character to a particular landscape [11]; and two, acknowledge the difficulties to approach landscape issues from a single research field.

A landscape is a complex system, a physical and non-material living organism in constant re-definition responding to the uses, values, resources, and conditions of those embedded in it. It can be assumed as a physical, social, historical, economic, cultural, or political object, both fixed and changeable, and with the capacity to link a number of various—sometimes conflicting—actors and norms. The recognized multifunctional and adapting capacities of landscapes in the scientific sphere demands a far more interdisciplinary approach to contemplating landscape issues [12]. Landscape is hereby assumed as a concept that goes beyond geographical boundaries: “a socio-ecological system consisting of a mosaic of natural and/or human-modified ecosystems, with a characteristic configuration of topography, vegetation, land use, and settlements that is influenced by the ecological, historical, economic and cultural processes and activities of the area” [11] (p. 4).

From the vast ocean of “bundles” of multifunctional services, practices, and outputs [8] embedded in a landscape, we focus on food systems to discuss landscape issues. According to Ericksen (2010), a food system is the specific set of multi-sectoral actors, processes and resources depicting the fluxes and tensions in producing, processing, and packaging food, distributing and retailing food, and consuming food (i.e., linking commodity chains to consumers) [1]. This concept of a food system serves as an analytical tool to link the multiple activities and discuss the political and social dimensions and arrangements in a landscape, because food system activities and outcomes result in processes that feedback to environmental and socioeconomic drivers [1] (p. 29).

The symbiotic dependence between elements and qualities in a food system have forged concerns over the sustainability of natural resources—such as biodiversity, habitats and water, and cultural heritage that make up landscapes. According to Selman (2008), evidence for the sustainability of landscapes is often related to their multifunctionality, an important paradigm within sustainable development thinking [8] (p. 180). Our approach to sustainable food systems goes beyond a focus on productivity—for example, on “productive rural areas”, “sustainable agriculture”, “sustainable forestry”, “sustainable fisheries” or “ecotourism”, which are all approaches putting emphasis upon economic sustainability [13] (p. 192). The debate about the polarization between more intensive and more extensive use of land [13] (p. 190) is considered herein, but the discussion does not limit itself to this. Preferably, it centers on a landscape approach to sustainable food production, natural resource conservation, and livelihood security goals that aim to better understand and recognize the interconnection between different land uses and the stakeholders that benefit from them [14] (p. 1). In other words, for a food system to be sustainable, there must be coherence in the landscape, which results from the articulation of various actors, areas, and other components in natural and/or socio-economic processes [11] (p. 11).

According to Robinson (2004), “sustainability is more usefully thought of as an approach or process of community-based thinking that indicates we need to integrate environmental, social and economic issues in the long-term perspective” and that “sustainability is itself the emergent property of a conversation about what kind of world we collectively want to live in now and in the future” [4] (p. 10). Our core understanding for sustainable landscape is comprehensive and political, embraces the agency component within it, and is based on the basic definition the World Commission on Environment and Development came up with in 1987 on sustainable development: “development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [15] (p. 1).

2.2. Landscape Governance and Food Systems

For over thirty years, new governance alternatives have followed a paradigm shift toward multifunctional land use and ecosystem service provision to address sustainability concerns from various angles. One of these is landscape governance, which has evolved as a holistic approach to complex systems, recognizing the set of rules—policies and cultural norms—and decision making processes of public, private, and civil sector actors that hold a stake in the dynamics that affect the landscape [11] (p. 5). Theoretical and empirical work on landscape governance systems has become instrumental in giving value to the interests of multiple actors and foster strategies for “constructing specific knowledges that acknowledge, reconcile, translate and co-create multiple perspectives that are essential in managing the functions and realizing the performance outcomes of the landscape” [14] (p. 9). Nevertheless, literature hints at the call for a more inclusive and heterogeneous landscape governance approach [12].

According to Macleod et al. (2007) and Selman (2008), “new ways of holistic landscape planning for sustainability require a collective delivery framework that moves passed the policy framework and includes a wider range of actors into the debate”. Such approach, they argue, will benefit from increased levels of integration between the natural and social sciences, land, forest and water managers, planners and policy makers across multiple landscape scales and levels of governance from landowner to national strategic governance [8]. Cavicchi and Ciampi Stancova (2016) also argue that policy frameworks used in one place may not necessarily bear the same fruit in another context, and, therefore, a case-by-case approach should be adopted to define specific governance instruments suited for each specific landscape: “A one size fits all recipe does not exist and the search for a solution implies a wise stakeholders’ management. Thus, every territory, every community, every district, or rural area, having different characteristics, cultural and economic backgrounds, need to be “discovered” through participatory approaches” [16].

The food systems analysis in this paper appears adequate to expand the scope of the landscape governance approach, thanks to the inherent complexity of actors, levels, processes, and tensions within food systems. We adopt Friedmann’s (2004) institutional food regimes approach to understand food systems governance, by looking into the “complementary expectation governing the behavior of all social actors—such as farmers, firms, workers, government agencies, citizens, and consumers—engaged in all aspects of food growing, manufacturing, distribution and sales.” [17]. Along with Kozar el al. (2014), we assume food systems to be concerned with the “institutional arrangements, decision-making processes, policy instruments and underlying values in the system, by which multiple actors pursue their interests in sustainable food production, biodiversity and ecosystem service conservation and livelihood security in multifunctional landscapes” [14] (p. 8).

The challenges in landscape governance pointed out by the same authors are relevant for food systems analysis too and underpin the discussion within this paper: (i) negotiating what and whose landscape is being governed; (ii) reconciling social and ecological boundaries and scales; (iii) resolving governance options and metrics of evaluation; and, (iv) balancing power dynamics [14] (p. 15). As landscape practitioners, we build on the holistic, multi-actor and multi-level landscape governance approach to explore diverse ways within whole food systems governance to discover ‘generative forms of power’ that pull actors together through collective action, and avoid designing systems that allow power imbalances to prevail [14] (p. 10). By the same token, we prioritize a cross-sectoral, multi-stakeholder cooperation and benefit distribution of resources and outputs when debating food systems governance within this approach.

3. Case Study—The Autonomous Region of the Azores, Portugal (ARA)

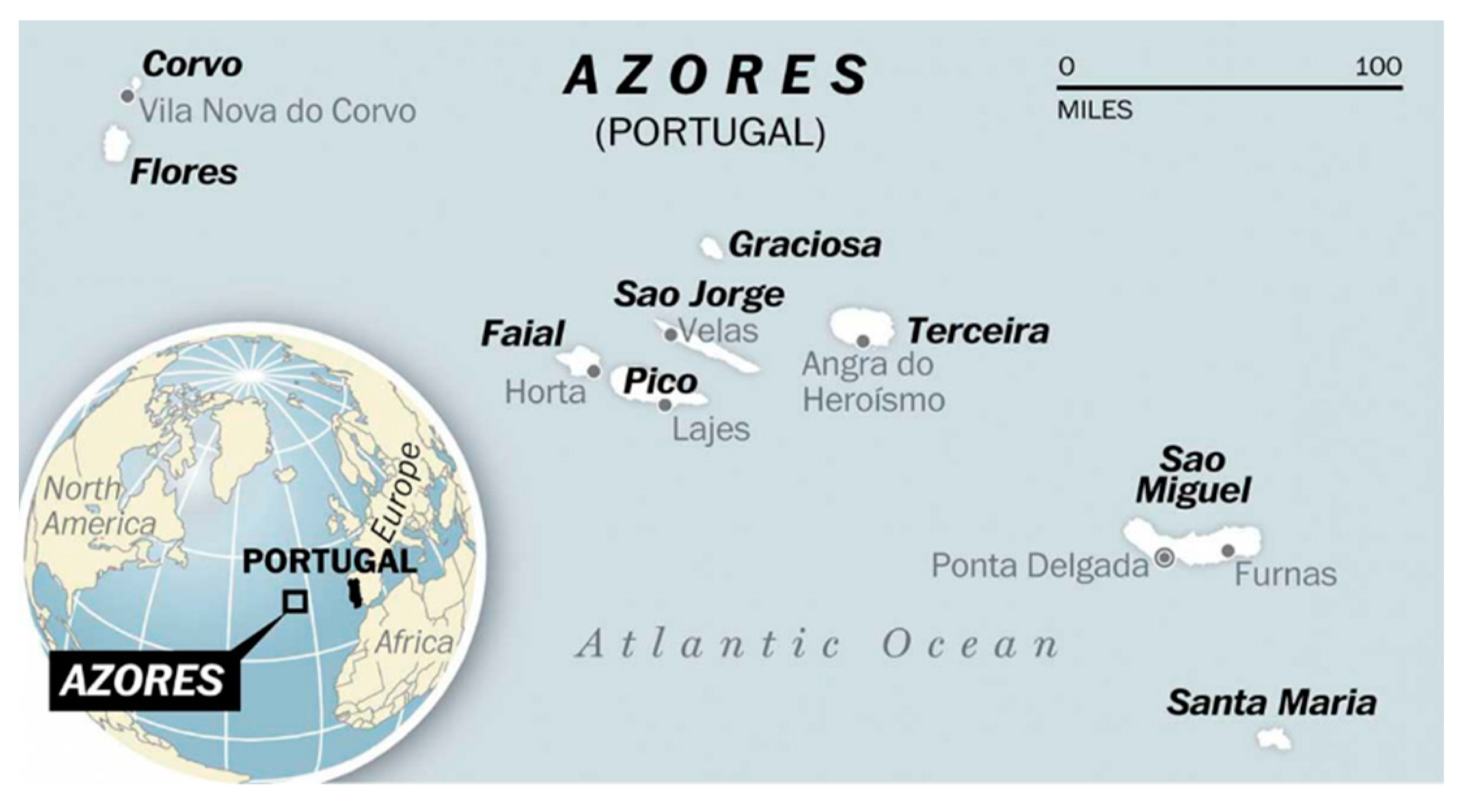

The Azores is a set of nine islands located in the Atlantic Ocean about 1500 km off the Iberian Peninsula in Europe (Figure 1). Populated by Portuguese since the 15th Century and today part of the European Union (EU) as one of its outermost regions, the archipelago of the Azores celebrates its title as one of the Portuguese Autonomous Regions since 1976.

Figure 1.

Map of the Azores. From: Live Azores website [20].

Before Portugal adhered to the EU, the Azores region was structurally underdeveloped with very low levels of wealth production [2]. This situation did not change much until the end of the 1990s, following a convergence strategy with mainland Portugal and Europe that promoted an economic growth boosted by the contribution of resources provided by Community funds [2]. Due to the disadvantages of their geographical location, EU programs have specific measures for OR in areas such as customs and trade policies, fiscal policy, free zones, agriculture and fisheries policies, and conditions for supply of raw materials and essential consumer goods [18]. In ARA, support funds have mainly aimed at mitigating additional supply costs involved in livestock farming and vegetable production, commercialization, transformation, and in measures for increased knowledge skills and technical support [19].

The Azores is classified as a predominantly rural and a transition region, whose fundamental pillar of the economy is agriculture, an activity exposed to damage from natural catastrophes and bad weather [3]. Therefore, ARA’s economy has often been described as vulnerable and with a very high dependence upon its primary sector, in socio-economic (employment), territorial (landscape) and natural (resources) aspects [3] (p. 21).

The ARA presents nowadays a low population density centered on large-scale cattle farming for milk and meat production. Lobo (2005) claims there are as many cows as people in the islands and milk production has almost doubled by the turn of the century, representing one third of the total national production, while causing the environmental degradation of water ecosystems [4] (p. 2). Meat slaughtering has increased in the last 15 years following a substantial investment in modernization of regional abattoirs [2].

Production of fruits and vegetables is residual, mostly for self-consumption, with crops such are potato, beetroot, corn for grain, sweet potato, and Azores yam [3]. Relevant agricultural crops for the regional economy—mostly for export outside the region—include wine grapes, orange, banana, pineapple, and tea; however, the main crop in terms of production and surface area is green maize, which is directly linked to livestock production [3]. Fishing, on the other hand, encompasses a small-scale artisanal activity that relies heavily on tuna despite its economic potentiality from vast marine diversity [2] (p. 26).

4. Methodology

This paper uses primary data from Hernández (2016) [10], which exposes the ongoing tensions and conflicts among actors, institutions and discourses shaping the political aggregation and representation of interests in the Autonomous Region of the Azores. Hernández (2016) data set of stakeholders’ perceptions is the raw material we use to embark into a discussion about sustainable landscape governance, thanks to its multi-actor, cross-sectoral and multi-level nature.

Data were collected from March to July of 2016 in Terceira Island—the third biggest island in surface and second in place in contributing to the Azores’ gross-added value—from eleven semi-structured individual interviews and six events linked to the ARA’s food system. Interviewees and events were selected giving priority to the regional scope before the local perspective (e.g., Regional Directorate of Agriculture; Regional Directorate for Rural Development; and First Regional Meeting on Community-based Local Development; among others). Nonetheless, research participants linked mainly to local issues in Terceira Island were also considered, due to their substantial leverage in regional affairs and/or to their informed knowledge about concerns at the regional level (e.g., Ship-owners’ Association from Terceira Island; Chamber of Commerce from Angra do Heroísmo; etc.). Fieldwork events crossed-cut across the food producing sector and ranged from gatherings about agricultural inputs to regional meetings on rural development and governance issues of the agri-food industry. At these, notes were taken in participant observation.

With the exception of one occurrence, data collection was mostly done in person in Terceira Island [21]. The selected participants and events were required to meet the following criteria to guarantee an inclusive and representative sample of ARA’s food system: (1) they needed to be part of any of the multiple activities of ARA’s food system: production, distribution, consumption and management; (2) they had to be ‘stakeholders’, meaning they must represent a group of constituents and have an active stake in debates pertaining to the food scheme in the Azores [22]; and (3) they needed to be willing to answer specific questions concerning this study—this applies only for interviews.

Interviews ranged from five to nine questions—often branching off in sub-questions on a case-by-case basis—and lasted one and a half hour in average. Questions sought to discover how research participants understand the dynamics and processes within ARA’s food system alternating from the macro to the micro level depending on the research participant (See Table A1 in Appendix A). The number of interviews and events was chosen arbitrarily, according to people’s availability, fieldwork time, location, and timing—for instance, in the case of relevant events, only those taking place in Terceira Island during fieldwork were considered. Therefore, the results presented in this study are a sample of the issues that concerns the food systems in the Azores case study and do not intent to represent the overall range of issues existing in all OR.

Most questions were tailored to relate to each actor’s sector, so they could answer from their own perspective, although a few questions were overarching to encompass the entire functioning of ARA’s food system. An example of a specific question is: “What is the role of the agricultural regional office toward attaining a strategic food reserve for the Region?” On the other hand, a general question was: “How does the institution you are affiliated to guarantee the representation of food producers from all sectors?”

Transcripts were intentionally organized to do line-by-line discourse analysis (microanalysis) using Atlas.ti qualitative analysis software [23]. Microanalysis was done in two phases: open-coding and axial-coding. Open-coding consisted of a thorough, focused, and intentional reading of each transcript to identify patterns. It was instrumental for breaking data down into discrete parts to examine them closely, compare their similarities and differences and, then, assign a code—or ‘label’. Groups of codes of similar nature and essence were classified into themes, which stood as ‘conceptual names’ explaining what stroke as significant or interesting to respondents. Furthermore, these codes were grouped into categories to “specify a theme further by responding when? where? why? and how? the phenomenon can occur” [24].

In axial-coding, subsequently, themes—also referred to as variables—were contextualized. This implied linking the conditions (micro and macro circumstances), actions and interactions (processes), and consequences (outcomes to interactions) inferred through the themes and the categories “to form more precise and concrete explanations about phenomena” [24] (pp. 124–127). Axial-coding helped acquire additional understanding about the layout of the food system in the Azores: specifically, on how participants interact with the institutions, as well as how they perceived central discourses, intervening forces, and occurring issues in the landscape.

The qualitative analysis of research participants’ perspectives developed by Hernández (2016) was further examined through the landscape governance approach to assess the Azores’ food system. Such exploration was inspired by the MALG developed by the Green Livelihoods Alliance in 2017 [11] (p. 7). Tropenbos International and EcoAgriculture Partners developed this Methodology for the purpose to identify and monitor changes in landscape governance and enable learning among its stakeholders.

We followed the four performance criteria suggested in the Manual to evaluate the landscape governance systems, or negotiation-supporting systems [11] (p. 8) that exist—or are lacking—in ARA’s food system: (i) inclusive decision-making in the landscape; (ii) culture of collaboration in the landscape; (iii) coordination across landscape sectors, levels, and actors; and (iv) sustainable landscape thinking and action.

Selected transcripts containing research participants’ perspectives about the functioning of ARA’s food system in Hernández (2016) were emblematically chosen to support each of the four performance criteria in the MALG. With the objective to contextualize research participants’ arguments, every transcript includes the corresponding sector and level to which they operate within the Azores’ food system. If they hold a stake at the Azorean level, it is categorized as “regional”; if they only operate within the island level, it is named “local”; whereas, if the stakeholder operates nationally, it is called “national”. The definitions and characteristics of each criterion were directly taken from the MALG, which helped us to present clearly key issues on sustainable landscape governance through our data in the Azores.

5. Results

The results of our study correspond to key issues on sustainable landscape governance identified in ARA’s food system. They are presented following a classification based on the four performance criteria suggested by the MALG: (i) inclusive decision-making in the landscape; (ii) culture of collaboration in the landscape; (iii) coordination across landscape sectors, levels, and actors; and (iv) sustainable landscape thinking and action.

5.1. Inclusive Decision—Making in the Landscape

Inclusive decision-making in landscape looks at what actors and under what conditions those actors get to participate in decision-making processes, and whether accountability mechanisms are in place to ensure decision-makers are held accountable for their decisions. Various stakeholders were highlighted through data collection as responsible for the design of the food system in the Azores. Most of them are under the umbrella of the regional government, although some are non-state actors.

A discrepancy in sectoral participation in decision-making processes was made evident. For instance, the primary sector was mostly linked to the farming sector.

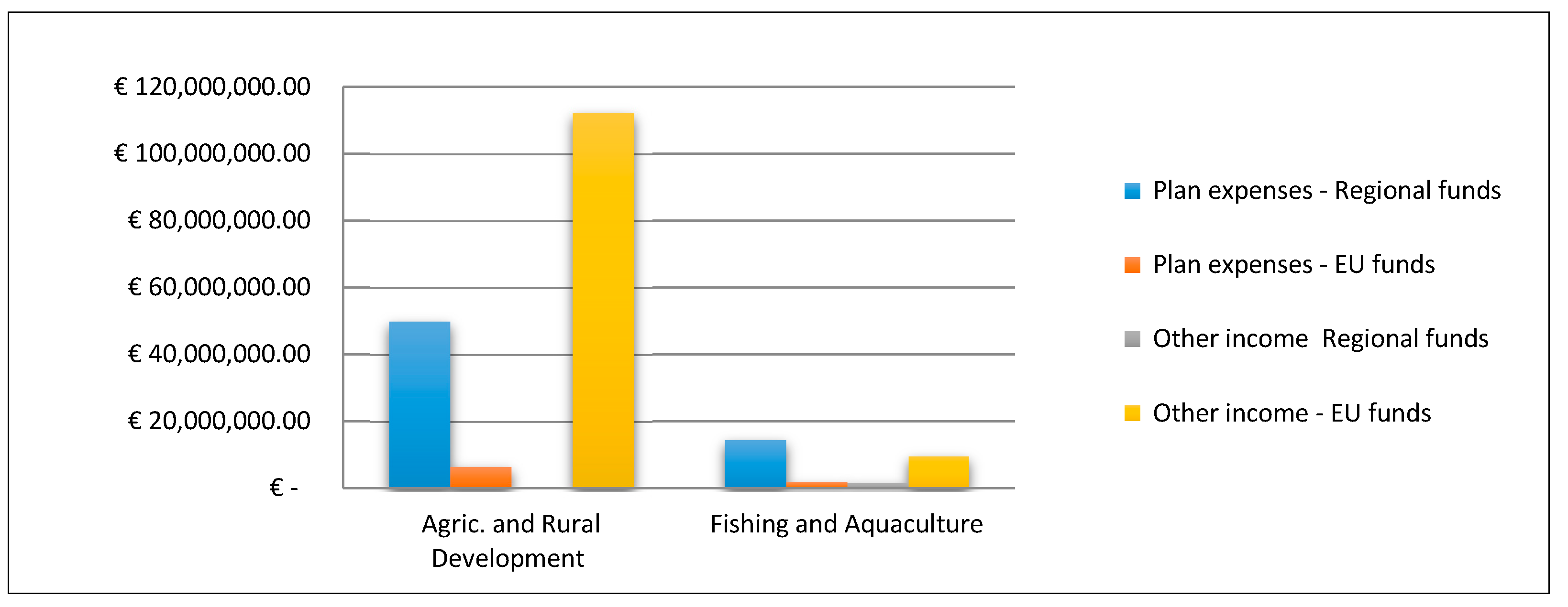

Given the relevance of agriculture for the Region, the Regional Secretariat for Agriculture and the Environment (SRAA) is held responsible for implementing the agricultural and environmental policies in the Region, which often fall under the rural development scope. On the contrary, the Regional Secretary for the Sea, Science and Technology (SRMCT) holds little stake in food affairs in the Azores. Several aspects were argued to justify this situation: first, the Regional Directorate for Fisheries (nested in SRMCT) deals mostly with the fishing industry; second, fishermen, and ship-owners’ issues are largely dealt through each of the islands’ associations; third, there is a significant difference in budget allocation between the agricultural and fishing sector (see Figure 2); and last, a lack of representation of fishermen in the Region was inferred through data analysis.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the Autonomous Region of the Azores’s (ARA) budget allocation by department in 2016, according to the Regional Legislative Decree No. 1/2016/A [25].

Adequate representation of farmers from all nine islands in the Azores was argued to take place through the Azorean Farmers Association (FAA).

“At the FAA, all islands in the Azores are represented, including producers’ organizations linked to (product) diversification, whose opinions and comments regarding the regional agricultural policy are also taken into account.”—Primary Sector (regional)

However, a somewhat centralized sectoral representation by this association, at least formally, was mentioned:

“There was an attempt to have an advisory board to hold formal meetings between farmer associations and farmers, but it did not succeed. Informally today, it is through the Azorean Farmers Association (FAA) that the different (agricultural) associations can have access to the regional government (ARA).”—Administration Sector (regional)

Fieldwork data reveals that not all cross-sectoral stakeholders hold the same bargaining capacity in the Azores. For instance, an uneven playfield appears to favor food industry actors over those representing primary food producers:

“Subsidy application (for fishermen) is done through the ship-owners (who represent a business), because fishermen have little rights.”—Primary Sector (local)

A reduced participation of local actors in processes concerning the whole food chain was highlighted by research participants:

“Most of milk and meat is transformed by the industry. A big portion of meat is exported and contact with the final consumer is residual.”—Primary Sector (regional)

A lack of effective mechanisms to hold stakeholders accountable for decisions concerning the food system processes in the Azores was expressed. Highlighted issues include the difficulties to assure liability and transparency from the regional authorities, which are necessary features for the promotion of a stimulating and participatory system.

“Labelling foodstuffs as GMOs [26] because they derive from animals fed on animal feed that could have possibly contain GMOs] might create confusion among consumers and also affect the ‘healthy and green’ image that the Azores has; for example, the ‘Milk from Happy Cows Program” [27].—Transformation Sector (local)

5.2. Culture of Collaboration in the Landscape

This criterion refers to how rules and decision-making processes are embedded in the social landscape and looks at the relationships and interactions among various groups and sectors. Effective governance profits from a culture of collaboration among stakeholders toward the well-being of all landscape community members, while fighting exclusion and marginalization.

A low and limited participation of community members in decision-making processes was hinted at by the data. Reasons mentioned include the individual or collective lack of interest in participating and the current food system’s setup. Similarly, data indexed a reduced number of actors able to partake in the design of the food system:

“The community does not participate (in the creation of programs). For instance, the consumer does not intervene; the farmer participates little.”—Administration Sector (regional)

On the other hand, fruitful partnerships appear to bear fruit among actors with no competing interests (e.g., cases where all players benefit evenly, power dynamics are agreed upon beforehand, or funding sources differ).

“There is an Azorean Fish Producers Association (Federação das Pescas dos Açores, FPA), in which all regional associations are part of. The FPA represents all regional associations and acts as an advisory body before the South Western Waters Regional Advisory Council (SWWRAC), which includes Italy, Spain and Portugal.”—Primary Sector (local)

Participants described an incipient culture of collaboration among actors across ARA’s food system and the absence of an enabling environment that promotes innovation in governance.

“Although (the Region) had the opportunity to change (in 2006), the Azores decided to keep the status quo, meaning that strong forces were maintained … Political regional decisions (in ARA) are based on established interests.”—Administration Sector (regional)

5.3. Coordination across Landscape Sectors, Levels and Actors

Effective landscape governance requires coordination across actors, sectors, and scales, because integrated decisions and actions are longer lasting when interacting beyond the individual scale [11] (p. 7). Coordination in decision-making processes fosters the development of synergies and opportunities for collaborative actions in the landscape. Importantly, identifying such opportunities is possible when knowledge about landscape interactions and the sharing of knowledge and information prevails.

Data signals to a lack of clear, long-term objectives and a broader notion of what is at stake in the ARA’s food system. Some of the statements addressed actors that are performing in isolation and with short-term goals, as well as an absence of an integrated landscape planning strategy.

“In the ARA: there is no food policy. No one knows what is wanted, or who to sell to? There is no path.”—Transformation Sector (local)

“Today in ARA, isolated groups in various islands are working (as part of the organic movement) in disconnection from one other.”—Retail Sector (local)

Data registered research participants’ awareness about the need to increase synergies and promote cross-sectoral and multi-level collaboration in light of improving the system:

“We need to work at a regional and multidisciplinary level to reflect on the way we are seeing food. To do so, we must design a transversal policy that sees food beyond agriculture and considers aspects such as transportation, health, the role of consumers, and education.”—Political Party (regional)

Reference was given to multi-level monitoring mechanisms of regional food production processes. They were often justified in terms of their policing role rather than on their capacity to improve landscape coordination.

“In the ARA, an official control to monitor food products has to be done four times per month. Item number seven of the Official Control Plan for Raw Milk (PCOL) [28] obliges to do control of animal feed, which includes traceability. Requirements for this control include origin of animal feed.”—Administration Sector (regional)

The degree of horizontal coordination across sectors (for instance, among actors involved in a stage of the food chain—production, distribution, and consumption processes in the Region) indicates the level of landscape integration. According to the research participants, there is room for improvement in the coordination over the means of transportation, which in the case of the Azores are maritime and by air, and the distribution channels [29].

“Transportation is a constraint for distribution, especially in terms of longevity… We must first address the issues with transport and logistics (if we want to profit), because it takes up to six and seven days for produce to arrive to mainland Portugal.”—Administration Sector (regional)

Vertical coordination among sectoral government agencies and different jurisdiction levels seem to also be lagging behind in the Azores. Statements inform about the close control of tasks by governmental bodies over the public sphere and project management.

“The Services Division for Rural Development (DSDR) responds to the SRAA, which is the governmental entity that states what it wants and says what it needs to be done (regarding the approval of rural development projects).”—Administration Sector (regional)

Similarly, thoughts about micromanagement over ARA’s food system indexed frustration and absence of independence. Arguments claimed such approach can hinder effective teamwork and confidence among sector players.

“To the SRAA and its partners compete the planning, orienting, and accompanying of all processes in the field of science and agriculture. All these services must be set free. For example, application forms for funding could be transferred to the farmers’ associations.”—Political Party (regional)

5.4. Sustainable Landscape Thinking and Action

Sustainable landscape management refers to nature-based approaches to land use and natural resource management. This category includes sustainability concerns over the current food system; namely, due to its focus on the industrial farming model. Examples include the renewability of the primary food producers in the Azores and their fragile livelihoods.

“What is currently happening in the ARA is a suicide, taking away the farmers from the land to increase the dairy production in larger operations. This kills the family matrix!”—Transformation Sector (local)

Sustainability practices have followed increased EU project investments [3], linking sustainable agriculture, environmental protection, and cultural heritage. Examples include the “Milk from Happy Cows” campaign, which encourages cattle raising in free pastures with animals who have access to fresh grass all-year-around. Milk produced under this agro-ecological livestock production was claimed to be tastier and more nutritious than conventional ones. Other sustainable landscape management strategies include ARA’s protected natural reserves, agro-ecotourism, and the Marca Açores [30], which is a landscape labelling strategy intended to promote local foods and culture:

“Strategies (for the food and agriculture sector) in ARA include: (1) to prioritize high quality regional products; (2) to bring the name of the Azores higher (e.g., through the brand Marca Açores); (3) to invest on the dairy sector; (4) to increase food self-provision (e.g., by depending less on imports).”—Administration Sector (regional)

ARA’s reliance on imports of foodstuffs and production factors was repeated across data occurrences. Reasons for this included competitive prices, the absence of regional structures that could provide these items, and the lack of incentives to promote their production in the Region. A EU Parliament assessment paper on the effects of European Cohesion Policies (2015) supports respondents’ perspectives. The paper stresses that ARA’s geographic constraints [3] lead to considerable economic dependency on external sources for both regular funding and/or for extra charges related to their economic activities, which impede sustained economic development [31].

“… it is cheaper to import in bulk than to produce locally …”—Administration Sector (local)

Subjects referred to the need for a self-critical and self-reflexive assessment of how the current food regime is constructed in the Azores. Some of the perceived aims of this assessment included: Identifying the landscape’s shortcomings and ineffective measures; the amendment of the role of actors and legislations; and, the reformulation of social and political patterns for the improvement of the system as a whole.

“We must have the courage to accept where we have failed and reflect on how this can change? For this, we need a political will that accepts things need to change.”—Administration Sector (regional)

The results of our study correspond to key issues on sustainable landscape governance identified in ARA’s food system. They are presented following a classification based on the four performance criteria suggested by the MALG: (i) inclusive decision-making in the landscape; (ii) culture of collaboration in the landscape; (iii) coordination across landscape sectors, levels, and actors; and (iv) sustainable landscape thinking and action.

6. Discussion

A discussion from our results above is inspired by the four criteria suggested in the MALG (2017). Table 1 shows the direct arguments to each criterion, in light to assess the Azores’ food system governance. This presentation does not attempt to replicate the results, but to initiate a debate on sustainable landscape governance issues. Discussion points summarize the arguments behind research participants’ perspectives, while linking them to the characteristics described for each assessment criterion. A third column includes a set of policy recommendations that respond to the shortcomings and opportunities identified under each criterion, which are intended to propose concrete actions that promote sustainable landscape governance in the Azores food system.

Table 1.

Summary of the ratifying arguments to the four criteria proposed in the Manual for Assessing Landscape Governance—MALG (2017).

7. Conclusions

We have empirically and theoretically explored in this paper the importance to develop sustainable food systems governance assessments from a landscape perspective, moving passed the geographical definition of landscape, assuming multifunctional land use and ecosystems, and including both natural and human-modified aspects inherent to landscape. We deployed the Azores Region as a sample of the issues concerning food system governance and the results do not intend to represent the overall range of issues existing in all outermost regions in Europe.

We adopted Ericksen’s multi-level, multi-actor, and holistic approach to understand food systems (Ericksen, 2007, 2008, 2010) [1,8,33] and to unveil the complexity behind the Azores food system. Assuming such a concept enabled us to recognize the flows, effects, networks, and relationships in food system processes in this remote European region. The assessment tool developed by the Green Livelihoods Alliance (2017) was used on the case study to examine the challenges and opportunities of sustainable food systems governance in this region. The four performance criteria suggested in the Manual for Assessing Landscape Governance (2017) proved to be instrumental in carrying out a bottom-up and inclusive analysis on sustainable food systems governance in the Azores. Adopting this methodology, we were able to identify the specificities of the landscape governance of Azores’ food system, as well as the conflicting interests among the actors and outcomes. The level of conflict needs to be decreased and this can be improved by a continuous debate between different actors regarding the present food system and future perspectives. Steps in this direction are suggested in a series of policy recommendations drawn from the study results, which can realistically be implemented at the regional level in the Azores.

The exemplary case study assessment of the Azores hereby analyzed is a stepping stone toward broadening knowledge about governance issues in this Outermost Region of Europe. Further studies are encouraged to adopt the landscape governance approach to discover the set of rules and decision-making processes that define the challenges and opportunities for them to develop sustainable food systems. Moreover, future research can be fruitful to explore the cross-fertilization of regional and national policies, especially in light of European Union Cohesion Policy and food-related policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A.H. and M.H.G.; Investigation, P.A.H.; Methodology, P.A.H.; Validation, P.A.H.; Writing—original draft, P.A.H.; Writing—review and editing, P.A.H., M.H.G., M.R. and E.S.

Funding

This work is funded by National Funds through FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology under the Project UID/AGR/00115/2013/ and the SALSA Project—Small farms, small food businesses and sustainable food and nutrition security—(Project ID: 677363) funded under H2020-EU.3.2.—Societal Challenges—Food security, sustainable agriculture and forestry, marine, maritime and inland water research and the bioeconomy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all three anonymous reviewers who contributed to this paper with insightful and pertinent comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Interview script used during individual and semi-structured interviews for fieldwork data collection in Terceira Island, Azores (2016).

Table A1.

Interview script used during individual and semi-structured interviews for fieldwork data collection in Terceira Island, Azores (2016).

| Question Type | Question Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Generic

|

|

| 2 | Specific

|

|

References and Notes

- Ericksen, P.; Stewart, B.; Dixon, J.; Barling, D.; Loring, P.; Anderson, M.; Ingram, J. The Value of a Food System Approach. In Food Security and Global Environmental Change; Ingram, J.S.I., Ericksen, P.J., Liverman, D.M., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; Chapter 2; pp. 25–45. ISBN 9781849711272. [Google Scholar]

- The OR include: Guadeloupe, French Guiana, Martinique, Réunion, Saint-Martin, the Azores, Madeira and the Canary Islands), which are regions that have a geographic distance from the European continent. They are usually islands, in a situation of being an enclave, or with challenging topographical and climate conditions, causing them to be removed from the main commercial trade lines, economically dependent on a few products, and therefore with restraints to take full advantage of the European Market. From: The Outermost Regions of the European Union: Towards a Partnership for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth; Report, COM (2012)287 of 20/06/2012; Assumptions and Context for the Action Plan 2014–2020; In the Context of the Communication from the European Commission, June 2013. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/communications/2012/the-outermost-regions-of-the-european-union-towards-a-partnership-for-smart-sustainable-and-inclusive-growth (accessed on 13 June 2014).

- Massot, A. The Agriculture of the Azores Islands; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, G.; Costa, S.; Nogueira, R.; Antunes, P.; Brito, A. A Scenario Building Methodology to Support the Definition of Sustainable Development Strategies: The Case of the Azores Region. In Proceedings of the 11th Annual International Sustainable Development Research Conference, Helsinki, Finland, 6–8 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dentinho, T.P.; Fortuna, M.A.; Luís, R.G.; Vieira, J.C. Evaluation of the European Policies in Support of Ultraperipheric Regions, Azores, Madeira, Canarias, Guadalupe, Martinique, Guyane and Reunion. In Proceedings of the European Regional Development Issues in the New Millennium and Their Impact on Economic Policy, Zagreb, Croatia, 29 August–1 September 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ericksen, P. What is the vulnerability of a food system to global environmental change? Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobal, J.; Khan, L.K.; Bisogni, C. A conceptual model of the food and nutrition system. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southern, A.; Lovett, A.; O’Riordan, T.; Watkinson, A. Sustainable landscape governance: Lessons from a catchment based study in whole landscape design. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 101, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moragues-Faus, A.; Sonnino, R.; Marsden, T. Exploring European food system vulnerabilities: Towards integrated food security governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 75, 184–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, P.A. Discussing Food Sovereignty in the Context of a Globalized Food Market—The Case of the Autonomous Region of the Azores in Portugal. M.A. Thesis, University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- De Graaf, M.; Buck, L.; Shames, S.; Zagt, R. Assessing Landscape Governance: A Participatory Approach; Tropenbos International and EcoAgriculture Partners: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017; ISBN 9789051131383. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, J.; Tress, B.; Tress, G. Multifunctional Landscapes: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Landscape Research and Management. In Proceedings of the International Conference on “Multifunctional Landscapes”, Roskilde, Denmark, 18–21 October 2000; Centre for Landscape Research: Roskilde, Denmark, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M. Sustainable Landscapes: Contradiction, fiction or utopia? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozar, R.; Buck, L.E.; Barrow, E.G.; Sunderland, T.C.H.; Catacutan, D.E.; Planicka, C.; Hart, A.K.; Willemen, L. Toward Viable Landscape Governance Systems: What Works? EcoAgriculture Partners: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J. International Society for Ecological Economics; Internet Encyclopaedia of Ecological Economics: Sustainability and Sustainable Development. Available online: http://isecoeco.org/pdf/susdev.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2015).

- Cavicchi, A.; Ciampi Stancova, K. Food and Gastronomy as Elements of Regional Innovation Strategies; JRC Science for Policy Report; EUR 27757 EN; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, H. Food Regimes and Food Regime Analysis: A Selective Survey. In Proceedings of the Conference Land Grabbing, Conflict and Agrarian Environmental Transformations: Perspectives from East and Southeast Asia, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 5–6 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, F.; Outermost Regions (ORS). In Fact Sheets on the European Union. European Parliament, 2018. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/ftu/pdf/en/FTU_3.1.7.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2018).

- Report on the Execution of the Sub-Programme for the Autonomous Region of the Azores within the Global Portuguese Programme 2013. Regional Secretary for Agriculture and the Environment 2014. Available online: http://posei.azores.gov.pt/ficheiros/14201516630.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2018).

- Map of the Azores. In the Azores Paradise a Few Hours from North America and Canada, 9 January 2016, Live Azores Website. Available online: http://liveazores.com/the-azores-paradise-a-few-hours-from-north-america-and-canada/ (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Alternatively, the interview was adapted into a questionnaire sent via email instead.

- In the case of events, they needed to be “platforms” where stakeholders would discuss food-related issues in the Region.

- A free trial version of Atlas.ti for Mac (Version 1.0.48) was chosen because of its simplicity.

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0803959408. [Google Scholar]

- The Official Budget for 2016 in ARA, as Approved by the Legislative Assembly (Discriminated by Departments). Three Out of the Four Rural Development Projects Expected for 2016 Are Agriculture-Oriented. From 2016 Official Budget for the Autonomous Region of the Azores, Decree 1/2016/A. In Diário da República. 8 January 2016, Volume 5. Available online: https://dre.pt/application/conteudo/73070297 (accessed on 8 August 2016).

- The Term Genetically Modified Organism (GMO) Is Any Organism, with the Exception of the Human Being, in which the Genetic Material Has Been Altered in a Way that Does Not Occur Naturally by Mating and/or by Natural Recombination. From Glossary of the Common Agricultural Policy. In Glossary of Terms Related to the Common Agricultural Policy. European Commission. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/glossary/index_en.htm (accessed on 14 March 2016).

- The ‘Milk from Happy Cows Programme’ (Programa Leite de Vacas Felizes) Is an Initiative in Cooperation between Terra Nostra—A Cooperative of Dairy Farmers Located in the São Miguel Island—And the Azorean Dairy Producers. It Lies on Five (5) Pillars: Year-Round Grass Feeding; Animal Welfare; Quality and Food Safety; Sustainable Production; and, Efficiency. From The Milk from Happy Cows Programme (Programa Leite de Vacas Felizes). Available online: http://www.terra-nostra.pt/programa-de-leite-de-vacas-felizes (accessed on 7 March 2016).

- PCOL (Plano do Controlo do Leite Cru). A Portuguese National Scheme for Raw Milk Control Was Implemented According to Regulation (EC) No. 852/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the Hygiene of Foodstuffs. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02004R0852-20090420&from=EN (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Neilson, A.L.; Cardwell, E.; Bulhão Pato, C. Coastal fisheries in the Azores, Portugal—A question of sovereignty, sustainability and space. In European Fisheries at a Tipping-Point, 1st ed.; Hojrup, T., Schriewer, K., Eds.; Ediciones de la Universidad de Murcia (Editum): Murcia, Spain, 2012; Chapter 4; pp. 465–505. ISBN 8415463154. [Google Scholar]

- The ‘Marca Açores’ Certificate Is a Marketing Strategy Spearheaded by the Society for the Development of Businesses in the Azores (SDEA) for Products Produced in the Azores. The Label Serves as an Iconic Image that Emotionally Links Products to Their Azorean Roots, While Informing Consumers about the Implementation of Principles that Respect the Archipelago’s Traditions and Nature. From Investinazores—Agro Food Sector. Available online: http://www.investinazores.com/index.php/en/why-azores/agro-food-sector (accessed on 13 June 2018).

- Trujillano, C.; Font, M.; Jorba, J. The Ultraperipheral Regions of the European Union: Indicators for the Characterisation of Ultraperipherality. In The INTERREG III B Community Initiative Programme for the Promotion of Cooperation between European Union Regions during the Period 2000–2006; Mcrit: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pouncy, C. Food Globalism and Theory: Marxian and Institutionalist Insights into the Global Food System. Univ. Miami Inter Am. Law Rev. 2011, 43, 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ericksen, P.J. Conceptualizing food systems for global environmental change research. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).