Impact of Perceived Uncertainty on Public Acceptability of Congestion Charging: An Empirical Study in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Congestion Charging Case Study

2.2. Influencing Factors on Public Willingness to Accept Congestion Charging

2.2.1. Congestion Charging System Attributes

2.2.2. The Use of Congestion Charges

2.2.3. The Effectiveness of Congestion Charging

2.2.4. The Fairness of Congestion Charging

2.2.5. Perception of the Congestion Problem

2.3. Perceived Uncertainty and Hypothesis Development

2.3.1. Perceived Uncertainty about Effectiveness

2.3.2. Perceived Uncertainty about Fairness

3. Methodology

3.1. Experiment Design

3.1.1. Attributes and Level Design

- The charging method attributes are mainly designed on two different levels, time-based charging, and intercepted charging. Time-based charging refers to collecting different fees for all road sections according to peak and non-peak periods of congestion. 7:00 to 9:00 and 17:00 to 19:00 are peak hours of congestion [54]. Intercepting charging here means that congestion charging is charged at the same price every day for a defined congested area. We set Beijing’s Third Ring Area as a charging area. For time-based charging, commuters who enter this area from 7:00 to 9:00 and 17:00 to 19:00 will be charged a peak-period charge, and they will be charged at a non-peak rate at all other times. For intercepted charging, at any time of the day, commuters will be charged if they enter the Third Ring Road area.

- The charging price attribute is set according to foreign experience, the amount of daily congestion charges collected accounts for about 5%–10% of the local residents’ income [55]. In 2016, the per capita disposable income in Beijing was 52,530 yuan (1 US dollar = 6.4379 yuan), and the amount of congestion charge in Beijing was between 7.19 and 14.39 yuan. According to the aforementioned charging methods, four different price levels are set at different peak and non-peak periods of congestion. The interception charging method is used to study the public’s willingness to choose different levels of price.

- At present, there is no uniform standard for the use of congestion charges. Typical examples include the three-point principle proposed by Small [23]. This article mainly refers to the distribution principle, while considering fairness in terms of the use of the revenue and the requirements of external costs, and finally determines the uses of the four types of congestion charging: (1) To subsidize government financial expenditures, (2) to improve construction of facilities such as road safety and road conditions, (3) to improve construction of public transportation facilities, and (4) to subsidize or reduce taxes on the use of vehicles.

3.1.2. Scenario Design

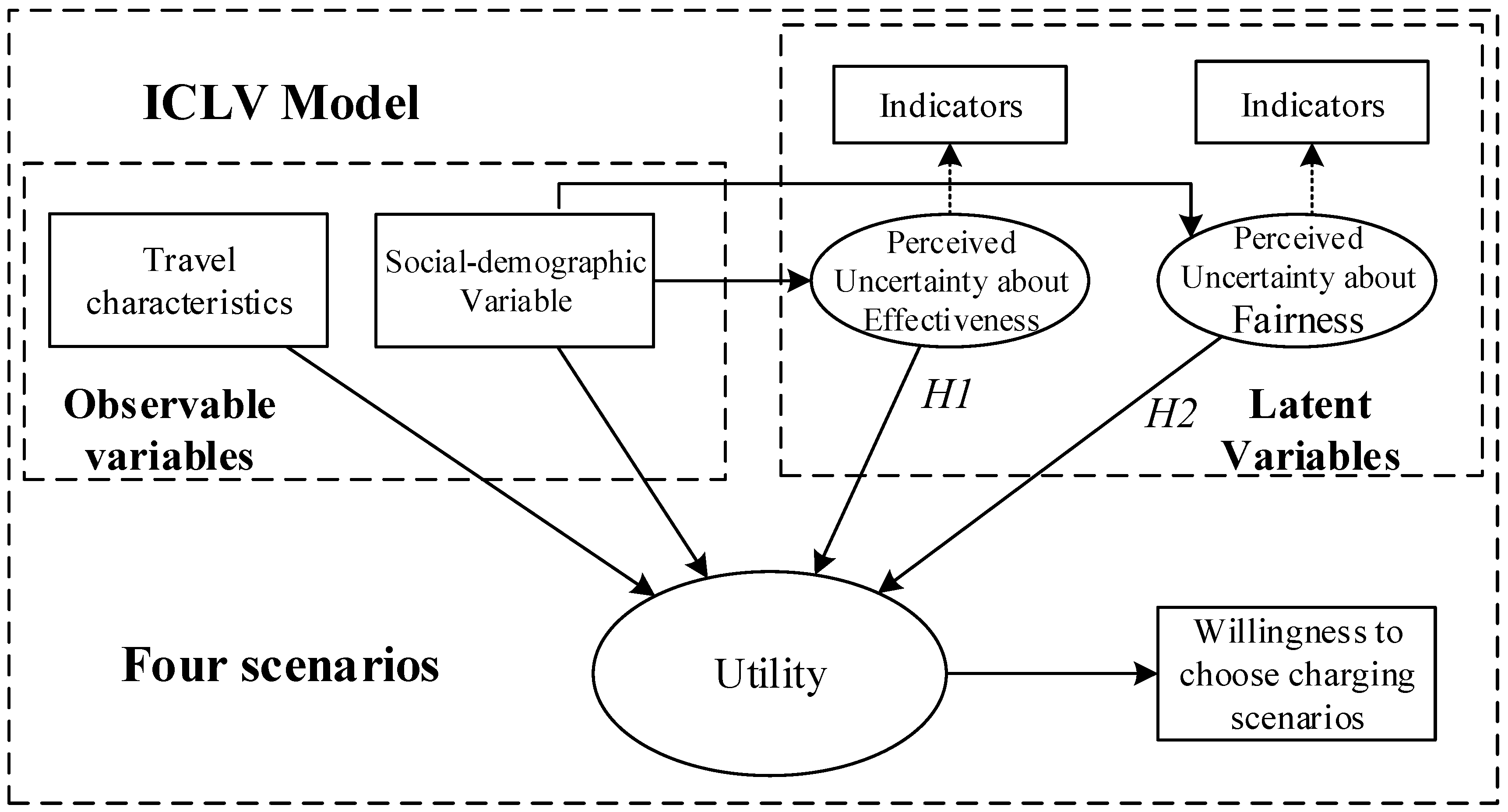

3.2. Model Construction

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Measurement

4. Results

4.1. Result of Latent Variable Model

4.2. Result of Choice Model

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion of Results

5.2. Implications

5.2.1. Social Characteristics

5.2.2. The Perceived Uncertainty of the Effectiveness of Congestion Charging

5.2.3. Perceived Uncertainty of the Fairness of Congestion Charges

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu, D.L. Public opinion anxiety behind “traffic congestion fee”. Leg. Dly. 2012, 2, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Hensher, D.A.; Li, Z. Referendum voting in road pricing reform: A review of the evidence. Transp. Policy 2013, 25, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hau, T.D. Congestion charging mechanisms for roads. parts i and ii. Transportmetrica 2006, 2, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leape, J. The london congestion charge. J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussone, L. Analysis of entering flows in the congestion pricing area C of Milan. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2017 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/I&CPS Europe), Milan, Italy, 6–9 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kockelman, K.M.; Jin, L.; Zhao, Y.; Ruíz-Juri, N. Tracking land use, transport, and industrial production using random-utility-based multiregional input-output models: Applications for texas trade. J. Transp. Geogr. 2005, 13, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsall, P.W.; Cho, H. Travellers Response to uncertainty: The particular case of drivers’ response to imprecisely known tolls and charges. In Transportation Planning Methods, Proceedings of Seminar F, European Transport Conference, Cambridge, UK, 27–29 September 1999; Transport Research Laboratory: Wokingham, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg, C.A.; Lawrence, S. Why government succeed: And why it doesn’t (jica). In Tackling Men’s Violence in Families-Nordic Issues & Dilemmas; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Balbontin, C.; Hensher, D.A.; Collins, A.T. Do familiarity and awareness influence voting intention: The case of road pricing reform? J. Choice Model. 2017, 25, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, R.C.; Lam, S.H.; Wu, P.H. Acceptability Tendencies and Commuters’ Behavior Under Different Road Pricing Schemes. Transportmetrica 2007, 3, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, J.; Puentes, R.; Winston, C. Easing the Traffic Jam through Congestion Pricing; Hamilton Project: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, W.; Krupnick, A.J.; Alberini, A. Overcoming public aversion to congestion pricing. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2001, 35, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ison, S. Local authority and academic attitudes to urban road pricing: A UK perspective. Transp. Policy 2000, 7, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuitema, G.; Steg, L.; Rothengatter, J.A. The acceptability, personal outcome expectations, and expected effects of transport pricing policies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, G.; Dudley, G.; Slater, E.; Parkhurst, G. Evidence Based Review Attitudes to Road Pricing; Faculty of Built Environment: Bristol, UK, 25 May 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ubbels, B.; Verhoef, E.T. Governmental competition in road charging and capacity choice. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2008, 38, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Sun, C.Y. Analysis of the public acceptability of congestion charge and its influencing factors—An empirical study based on Chengdu. China Manag. Inf. 2015, 18, 222–223. [Google Scholar]

- Schade, J.; Schlag, B. Acceptability of urban transport pricing strategies. Transp. Res. Part F Psychol. Behav. 2000, 6, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaensirisak, S.; Wardman, M.; May, A.D. Explaining variations in public acceptability of road pricing schemes. J. Transp. Econ. Policy 2005, 39, 127–154. [Google Scholar]

- Rienstra, S.A.; Rietveld, P.; Verhoef, E.T. The social support for policy measures in passenger transport: A statistical analysis for the netherlands. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 1999, 4, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlert, T.; Nielsen, O.A.; Rich, J.; Schlag, B. Public acceptability change of urban road pricing schemes. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Transport, August 2008; Volume 161, pp. 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, S.; Börjesson, M. Understanding attitudes towards congestion pricing: A latent variable investigation with data from four cities. Working Pap. Transp. Econ. 2017, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, K.A. Using the revenues from congestion pricing. Transportation 1992, 19, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahendra, A. Vehicle restrictions in four latin american cities: Is congestion pricing possible? Transp. Rev. 2008, 28, 105–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun, E.C.; Schiller, P.L. Does public transport relieve traffic congestion? Urban Transp. Int. 2008, 28, 105–133. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson, J. Lessons from the Stockholm congestion charging trial. Transp. Policy 2008, 15, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fridstrom, L. The truls-1 model for norway. In Structural Road Accident Models: The International Drag Family; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, N. research progress and practical difficulties in congestion road pricing. China Sci. Found. 2003, 4, 198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Oberholzer-Gee, F.; Weck-Hannemann, H. Pricing road use: Politico-economic and fairness considerations. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2002, 7, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odioso, M.S.; Smith, M.C. Perceptions of congestion charging: Lessons for U.S. cities from London and Stockholm. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium, Charlottesville, VA, USA, 25 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Effects of values, problem awareness, and personal norm on willingness to reduce personal car use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Garvill, J.; Nordlund, A.M. Acceptability of single and combined transport policy measures: The importance of environmental and policy specific beliefs. Transp. Res. Part A 2008, 42, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.; Brook, L. Public Attitudes to transport issues: Findings from the British social attitudes surveys. Transp. Policy Environ. 1998, 4, 72–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P. Acceptability of road user charging: Meeting the challenge. In Acceptability of Transport Pricing Strategies; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Odeck, J.; Bråthen, S. On public attitudes toward implementation of toll roads-the case of oslo toll ring. Transp. Policy 1997, 4, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souche, S.; Raux, C.; Croissant, Y. On the perceived justice of urban road pricing: An empirical study in lyon. Transp. Res. Part A 2012, 46, 1124–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, J.; Hultkrantz, L.; Nerhagen, L.; Rosqvist, L.S. The stockholm congestion-charging trial 2006: Overview of effects. Transp. Res. Part A 2009, 43, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.H.; Sun, X.L.; Lu, J. Public acceptability and effectiveness of congestion charging measures. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. 2014, 46, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson, C.; Fujii, S.; Gärling, T. Determinants of private car users’ acceptance of road pricing. Transp. Policy 2000, 7, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.L.; Lu, J. Public acceptability model of congestion charge based on structural equation. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2012, 44, 140–144. [Google Scholar]

- Link, H. Is car drivers’ response to congestion charging schemes based on the correct perception of price signals? Transp. Res. Part A 2015, 71, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliken, F.J. Three types of perceived uncertainty about the environment: State, effect, and response uncertainty. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsberg, D. Risk, ambiguity, and the savage axioms. Q. J. Econ. 1961, 75, 643–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Akiva, M.; Mcfadden, D.; Train, K.; Walker, J.; Bhat, C.; Bierlaire, M.; Bolduc, D.; Boersch-Supan, A.; Brownstone, D.; Bunch, D.S.; et al. Hybrid choice models: Progress and challenges. Mark. Lett. 2002, 13, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, W.; Zeckhauser, Z. Status quo bias in decision making. J. Risk Uncertain. 1988, 1, 7–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borger, B.D.; Proost, S. A political economy model of road pricing. J. Urban Econ. 2010, 71, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Q.; Feng, Y. Congestion pricing: An effective way to ease road traffic congestion in China. Integr. Transp. 2008, 7, 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hårsman, B.; Quigley, J.M. Political and public acceptability of congestion pricing: Ideology and self-interest. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2010, 29, 854–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Schmöcker, J.D.; Fujii, S.; Noland, R.B. Attitudes towards road pricing and environmental taxation among US and UK students. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 48, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verhoef, E.T. The social feasibility of road pricing. a case study for the randstad area. J. Transp. Econ. Policy 1997, 31, 255–276. [Google Scholar]

- Teubel, U. The welfare effects and distributional impacts of road user charges on commuters—An empirical analysis of dresden. Int. J. Transp. Econ. 2000, 27, 231–255. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.S.; Ma, F.Y.; Zhang, J.Y. The impact of equity perception and efficiency perception on the stability of supply chain cooperative relationship—Taking environmental uncertainty as a moderating variable. Enterp. Econ. 2012, 10, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Beijing Traffic Development Annual Report; Beijing Transport Institute: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Lu, Z.; Cui, Y.N. Comparison of traffic congestion fee system in developed areas and discussion of Beijing’s plan. Rev. Econ. Res. 2012, 2016, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa, T.; Ben-Akiva, M.; McFadden, D.L. Discrete choice models incorporating revealed preferences and psychometric data. In Advances in Econometrics; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raveau, S.; Álvarez-Daziano, R.; Yáñez, M.F.; Bolduc, D.; de Dios Ortúzar, J. Sequential and simultaneous estimation of hybrid discrete choice models: Some new findings. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2156, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, M.; Rye, T.; Allen, S. Public acceptability of road user charging: The case of edinburgh and the 2005 referendum. Transp. Rev. 2007, 27, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, J.; Mattsson, L.G. Equity effects of congestion pricing: Quantitative methodology and a case study for stockholm. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2006, 40, 602–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Countries/Cities | Singapore | Seoul | London | Stockholm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 1975 | 1996 | 2003 | 2006 |

| Charging area | Central Business District, highways, main roads | Main roads leading to downtown (Nanshan Highways 1 and 3) | Central London | City center |

| Charging periods | According to the size of traffic volume | Monday to Friday 7:00 to 19:00, Saturday 7:00 to 15:00 | Working days from 7:00 to 18:00, holidays are not levied | Working days 6:00 to 18:29, holidays are not collected |

| Prices charged | 0.5–5 Singapore dollars (1 SD = 0.7252 USD) | 2000 won (1 won = 0.0008852 USD) | 11.5 pounds (1 pound = 1.2975 USD) | Up to 30 kroons per time, up to 105 kroons per vehicle per day (1 Kroon = 0.1102 USD) |

| Use for congestion charges | Used for road and highway construction | Used to develop public transport | Used for traffic development in the area | For road construction |

| Attributes | Levels |

|---|---|

| Charging methods | Time-based charging; Intercepting charging |

| Charging price | (1) Time-based charging, Peak period/Non-peak period: 10 yuan/5 yuan; 12 yuan/6 yuan; 14 yuan/7 yuan; 16 yuan/8 yuan; (2) Intercepting charging: 7 yuan/9 yuan/11 yuan/13 yuan |

| Revenue allocation | (1) to subsidize government financial expenditure, (2) to construct facilities, including ensuring improved road safety and road conditions, (3) to improve construction of public transportation facilities, (4) to reduce taxes on the use of vehicles. |

| Scenario A | A1 | A2 |

| Charging method: Charging by time period | Charging method: Intercepting charging | |

| Charging price: High peak period is 10 yuan, and low peak period is 5 yuan | Charging price: 7 yuan for entering the charging area | |

| Revenue allocation: | Revenue allocation: | |

| To subsidize government spending | To subsidize government spending | |

| Scenario B | B1 | B2 |

| Charging method: Charging by time period | Charging method: Intercepting charging | |

| Charging price: High peak period is 12 yuan, and low peak period is 6 yuan | Charging price: 9 yuan for entering the charging area | |

| Revenue allocation: | Revenue allocation: | |

| To improve road safety, road conditions, and other construction | To improve road safety, road conditions, and other construction | |

| Scenario C | C1 | C2 |

| Charging method: Charging by time period | Charging method: Intercepting charging | |

| Charging price: High peak period is 14 yuan, and low peak period is 7 yuan | Charging price: 11 yuan for entering the charging area | |

| Revenue allocation: | Revenue allocation: | |

| 1. To improve road safety, road conditions, and other construction | 1. To improve road safety, road conditions, and other construction | |

| 2. To improve public transportation facilities | 2. To improve public transportation facilities | |

| Scenario D | D1 | D2 |

| Charging method: Charging by time period | Charging method: Intercepting charging | |

| Charging price: High peak period is 16 yuan, and low peak period is 8 yuan | Charging price: 13 yuan for entering the charging area | |

| Revenue allocation: | Revenue allocation: | |

| 1. To improve road safety, road conditions, and other construction | 1. To improve road safety, road conditions, and other construction | |

| 2. To improve public transportation facilities | 2. To improve public transportation facilities | |

| 3. To subsidize or reduce the use of vehicle-related taxes | 3. To subsidize or reduce the use of vehicle-related taxes |

| Socio-Demographic Attributes | No. | Pct. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 433 | 51.00% |

| Female | 416 | 49.00% | |

| Age (years) | Under 18 | 13 | 1.53% |

| 19–30 | 425 | 50.06% | |

| 31–45 | 235 | 27.68% | |

| 46–55 | 127 | 14.96% | |

| Over 55 | 49 | 5.77% | |

| Education level | High school and under | 125 | 14.72% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 456 | 53.71% | |

| Master’s degree and above | 268 | 31.57% | |

| Annual income | Less than ¥30,000 | 234 | 27.56% |

| ¥30,000–¥80,000 | 262 | 30.86% | |

| ¥80,000–¥200,000 | 257 | 30.27% | |

| More than ¥200,000 | 96 | 11.31% | |

| Job | Student | 173 | 20.38% |

| Private enterprise/self-employed/Freelancer | 151 | 17.79% | |

| Enterprise and institution workers | 314 | 36.98% | |

| Enterprise and institution managers | 124 | 14.61% | |

| National civil servants | 68 | 8.01% | |

| Retirement Employment | 19 | 2.24% | |

| Family members | 1–2 members | 97 | 11.43% |

| 3–4 members | 558 | 65.72% | |

| 5 or more members | 194 | 22.85% | |

| Private car | Yes | 394 | 46.41% |

| No | 455 | 53.59% | |

| Latent Variables | Indicators | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived uncertainty about effectiveness () | I1 Uncertainty about whether a congestion charge policy can effectively relieve congestion | Hensher and Li [2] |

| I2 Uncertainty about whether congestion charges can effectively save travel time | Hårsman and Quigley [49] | |

| I3 Uncertainty about the effect without a trial operation | Samuelson and Zeckhauser [46] | |

| I4 Uncertainty about whether charging equipment is accurate | Verhoef et al. [51] | |

| I5 Uncertainty about whether there will be a timely and effective response to the problem after implementation | Verhoef et al. [51] | |

| I6 Uncertainty about whether relevant departments can effectively implement congestion charging | Kim et al. [50] | |

| I7 Uncertainty about whether to choose alternative routes or travel modes | Verhoef et al. [51] | |

| I8 Uncertainty about travel cost | Borger and Proost [47] | |

| Perceived uncertainty about fairness () | I9 Uncertainty about whether the procedure for setting the congestion rates is fair | Hensher and Li [2] |

| I10 Uncertainty about whether the charging process is fair | Gaunt et al. [58] | |

| I11 Uncertainty about whether the use of congestion charges is fair | Gaunt et al. [58] | |

| I12 Uncertainty about whether congestion charges can be practically used in urban traffic construction | Jones [34] | |

| I13 Uncertainty about whether congestion charges are fair to different income groups | Jonas [59] | |

| I14 Uncertainty about whether the charges for different vehicle types (corporate cars and private cars) are fair | Borger and Proost [47] |

| Indicators | Perceived Uncertainty about the Effectiveness () | Perceived Uncertainty about Fairness () | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loading | T Value | Loading | T Value | |

| I1 Uncertainty about whether a congestion charge policy can effectively relieve congestion | 0.835 *** | 48.847 | ||

| I2 Uncertainty about whether congestion charges can effectively save travel time | 0.615 *** | 17.749 | ||

| I3 Uncertainty about the effect without a trial operation | 0.745 *** | 31.796 | ||

| I4 Uncertainty about whether charging equipment is accurate | 0.695 *** | 28.153 | ||

| I5 Uncertainty about whether there will be a timely and effective response to the problem after implementation | 0.579 *** | 16.208 | ||

| I6 Uncertainty about whether relevant departments can effectively implement congestion charging | 0.770 *** | 34.703 | ||

| I7 Uncertainty about whether to choose alternative routes or travel modes | 0.738 *** | 28.915 | ||

| I8 Uncertainty about travel cost | 0.707 *** | 26.093 | ||

| I9 Uncertainty about whether the procedure for setting the congestion rate is fair | 0.816 *** | 38.605 | ||

| I10 Uncertainty about whether the charging process is fair | 0.858 *** | 53.927 | ||

| I11 Uncertainty about whether the use of congestion charges is fair | 0.871 *** | 55.275 | ||

| I12 Uncertainty about whether congestion charges can be practically used in urban traffic construction | 0.541 *** | 3.551 | ||

| I13 Uncertainty about whether congestion charges are fair to different income groups | 0.748 *** | 27.164 | ||

| I14 Uncertainty about whether the charges for different vehicle types (corporate cars and private cars) are fair | 0.799 *** | 32.966 | ||

| McFadden’s R2 | 0.035 | 0.046 | ||

| Explanatory Variables | Perceived Uncertainty about the Effectiveness () | Perceived Uncertainty about Fairness () | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p Value | Coefficient | p Value | |

| Gender (X1) | 0.073 * | 0.078 | 0.099 *** | 0.006 |

| Age (X2) | 0.161 ** | 0.030 | 0.052 ** | 0.026 |

| Education level (X3) | −0.034 * | 0.052 | 0.084 ** | 0.029 |

| Annual income (X4) | −0.023 | 0.187 | −0.044 * | 0.081 |

| Occupation (X5) | −0.045 | 0.256 | −0.035 | 0.380 |

| Variable | Situation A | Situation B | Situation C | Situation D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNL | ICLV | MNL | ICLV | MNL | ICLV | MNL | ICLV | |

| Gender X1 | −0.954 *** | 0.848 ** | −0.821 ** | −0.703 ** | −0.472 * | −0.327 * | −0.776 ** | −0.647 * |

| Age X2 | −0.398 ** | −0.489 *** | −0.694 *** | −0.803 *** | −0.207 | −0.355 ** | −0.554 *** | −0.670 *** |

| Education level X3 | −0.532 ** | −0.610 * | −0.227 | −0.410 | −0.078 | −0.311 | −0.026 | −0.222 |

| Annual income X4 | 0.068 | 0.077 | 0.085 | 0.100 | 0.098 | 0.022 | 0.078 | 0.087 |

| Occupation X5 | −0.229 ** | −0.290 | −0.220 * | −0.193 | −0.239 * | −0.214 | −0.169 | −0.134 |

| Travel distance X6 | −0.183 | −0.036 | −0.107 | −0.340 | 0.532 | 0.320 | −0.042 | −0.294 |

| Travel time X7 | −0.201 | −0.200 | −0.289 | −0.296 | −0.285 | −0.307 | −0.337 * | −0.543 * |

| Travel frequency X8 | −0.295 * | −0.430 * | −0.275 | −0.375 | −0.248 * | −0.397 * | 0.097 | −0.054 |

| Delay time X9 | −0.033 | −0.038 | 0.112 | 0.061 | 0.098 | 0.036 | 0.116 | 0.107 |

| Travel mode X10 | 0.143 | 0.160 | 0.271 * | 0.247 * | 0.245 ** | 0.265 ** | 0.294 ** | 0.273 ** |

| Perceived uncertainty of congestion charging effectiveness | −0.326 * | −0.594 * | −0.838 ** | −0.616 ** | ||||

| Perceived uncertainty of congestion charging fairness | −0.711 ** | −1.098 *** | −1.167 *** | −1.045 *** | ||||

| Fitting Degree Index | MNL Model | ICLV Model |

|---|---|---|

| 0.315 | 0.335 | |

| AIC | 462.9 | 457.6 |

| BIC | 519.8 | 511.9 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, L.; Zhou, H. Impact of Perceived Uncertainty on Public Acceptability of Congestion Charging: An Empirical Study in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010129

Wang Y, Wang Y, Xie L, Zhou H. Impact of Perceived Uncertainty on Public Acceptability of Congestion Charging: An Empirical Study in China. Sustainability. 2019; 11(1):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010129

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yacan, Yu Wang, Luyao Xie, and Huiyu Zhou. 2019. "Impact of Perceived Uncertainty on Public Acceptability of Congestion Charging: An Empirical Study in China" Sustainability 11, no. 1: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010129

APA StyleWang, Y., Wang, Y., Xie, L., & Zhou, H. (2019). Impact of Perceived Uncertainty on Public Acceptability of Congestion Charging: An Empirical Study in China. Sustainability, 11(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010129