Environmental Homogenization or Heterogenization? The Effects of Globalization on Carbon Dioxide Emissions, 1970–2014

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Homogenous Environmental Consequences of Globalization

2.1. Ecological Modernization Theory

2.2. World Polity Theory

3. The Heterogeneous Environmental Effects of Globalization

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Datasets and Variables

4.2. Method

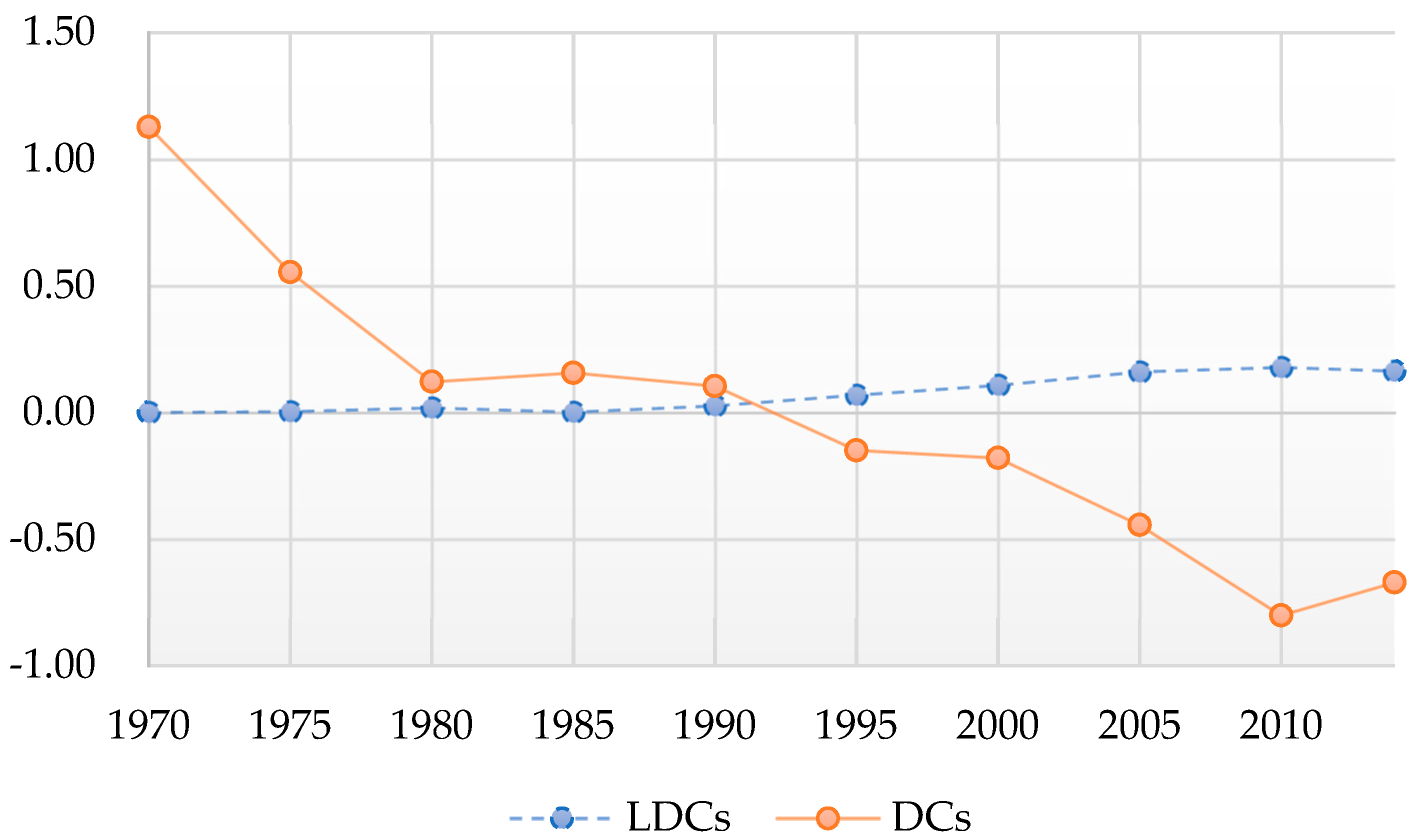

5. Results

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barkin, J.S. The Counterintuitive Relationship between Globalization and Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Politics 2003, 3, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; York, R. Carbon metabolism: Global capitalism, climate change, and the biospheric rift. Theory Soc. 2005, 34, 391–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Brulle, R.J. (Eds.) Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-19-935612-6. [Google Scholar]

- Givens, J.E.; Jorgenson, A.K. Global integration and carbon emissions, 1965–2005. In Overcoming Global Inequalities; Political Economy of the World-System Annuals; Wallerstein, I.M., Chase-Dunn, C., Suter, C., Eds.; Paradigm Publishers: Boulder, CO, USA, 2014; pp. 168–183. [Google Scholar]

- Longhofer, W.; Jorgenson, A. Decoupling reconsidered: Does world society integration influence the relationship between the environment and economic development? Soc. Sci. Res. 2017, 65, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mol, A.P.J. Globalization and Environmental Reform: The Ecological Modernization of the Global Economy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Prell, C.; Feng, K. The evolution of global trade and impacts on countries’ carbon trade imbalances. Soc. Netw. 2016, 46, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.T.; Parks, B.C. Ecologically Unequal Exchange, Ecological Debt, and Climate Justice: The History and Implications of Three Related Ideas for a New Social Movement. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2009, 50, 385–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G.; Mol, A.P.J.; Buttel, F.H. (Eds.) Environment and Global Modernity, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-0-7619-6767-5. [Google Scholar]

- Stretesky, P.B.; Lynch, M.J. A cross-national study of the association between per capita carbon dioxide emissions and exports to the United States. Soc. Sci. Res. 2009, 38, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A.P.J. Ecological Modernization and the Global Economy. Glob. Environ. Politics 2002, 2, 92–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A.P.J.; Sonnenfeld, D.A. (Eds.) Ecological Modernisation Around the World: Perspectives and Critical Debates; Frank Cass Publishers: London, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-0-7146-5064-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hornborg, A.; McNeill, J.R.; Alier, J.M. (Eds.) Rethinking Environmental History: World-System History and Global Environmental Change; Altamira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Parks, B.C.; Roberts, J.T. Globalization, Vulnerability to Climate Change, and Perceived Injustice. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J. Ecological Unequal Exchange: Consumption, Equity, and Unsustainable Structural Relationships within the Global Economy. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2007, 48, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, P.; Kentor, J. Exporting the Greenhouse: Foreign Capital Penetration and CO2 Emissions 1980–1996. J. World-Syst. Res. 2003, 9, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, A.K.; Dick, C.; Mahutga, M.C. Foreign Investment Dependence and the Environment: An Ecostructural Approach. Soc. Probl. 2007, 54, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.P.; Minx, J.C.; Weber, C.L.; Edenhofer, O. Growth in emission transfers via international trade from 1990 to 2008. PNAS 2011, 108, 8903–8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prell, C.; Sun, L. Unequal carbon exchanges: Understanding pollution embodied in global trade. Environ. Sociol. 2015, 1, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, A.; Gaston, N.; Martens, W.J.M. Measuring Globalisation Gauging Its Consequences; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 0-387-74067-8. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Runaway World: How Globalisation Is Reshaping Our Lives; Profile Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 1-86197-429-9. [Google Scholar]

- Guillén, M.F. Is Globalization Civilizing, Destructive or Feeble? A Critique of Five Key Debates in the Social Science Literature. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, D.; McGrew, A.; Goldblatt, D.; Perraton, J. Global Transformations: Politics, Economics and Culture; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-8047-3627-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pellow, D.N.; Brehm, H.N. An Environmental Sociology for the Twenty-First Century. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2013, 39, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G.; Mol, A.P.J. Sociology, environment, and modernity: Ecological modernization as a theory of social change. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1992, 5, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.T.; Grimes, P.E.; Manale, J. Social roots of global environmental change: A world-systems analysis of carbon dioxide emissions. J. World-Syst. Res. 2003, 9, 277–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandra, J.M.; London, B.; Whooley, O.P.; Williamson, J.B. International Nongovernmental Organizations and Carbon Dioxide Emissions in the Developing World: A Quantitative, Cross-National Analysis. Sociol. Inq. 2004, 74, 520–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.-K.; Shon, Z.-H. Emissions of greenhouse gases and air pollutants from commercial aircraft at international airports in Korea. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 61, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, A. Does Globalization Affect Growth? Evidence from A New Index of Globalization. Appl. Econ. 2006, 38, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, N. Time-Series–Cross-Section Data: What Have We Learned in the Past Few Years? Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2001, 4, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, N.; Katz, J.N. What to Do (and Not to Do) with Time-Series Cross-Section Data. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1995, 89, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, J.C.; Kraay, A.C. Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimation with Spatially Dependent Panel Data. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1998, 80, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoechle, D. Robust standard errors for panel regressions with cross-sectional dependence. Stata J. 2007, 7, 281–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordo, M.D.; Taylor, A.M.; Williamson, J.G. (Eds.) Globalization in Historical Perspective; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Berking, H. ‘Ethnicity is Everywhere’: On Globalization and the Transformation of Cultural Identity. Curr. Sociol. 2003, 51, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. Beyond state-centrism? Space, territoriality, and geographical scale in globalization studies. Theory Soc. 1999, 28, 39–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4443-1951-4. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, R. Globalization’s Cultural Consequences. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2000, 570, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A.P.J. The Refinement of Production: Ecological Modernization Theory and the Chemical Industry; Van Arkel: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 1995; ISBN 978-90-6224-979-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, A.P.J.; Sonnenfeld, D.A. Ecological Modernisation Around the World: An Introduction. In Ecological Modernisation around the World: Perspectives and Critical Debates; Mol, A.P.J., Sonnenfeld, D.A., Eds.; Frank Cass: London, UK, 2000; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, A.P.J.; Spaargaren, G. Ecological modernisation theory in debate: A review. Environ. Politics 2000, 9, 17–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G. The Ecological Modernization of Production and Consumption: Essays in Environmental Sociology; Landbouw Universiteit Wageningen: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, A.P.J. Ecological modernization: Industrial transformations and environmental reform. In The International Handbook of Environmental Sociology; Redclift, M., Woodgate, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 1997; pp. 138–149. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, A.P.J. Environment and Modernity in Transitional China: Frontiers of Ecological Modernization. Dev. Chang. 2006, 37, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G.; Mol, A.P.J. Carbon flows, carbon markets, and low-carbon lifestyles: Reflecting on the role of markets in climate governance. Environ. Politics 2013, 22, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J. Towards industrial ecology: Sustainable development as a concept of ecological modernization. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2000, 2, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J. Pioneer countries and the global diffusion of environmental innovations: Theses from the viewpoint of ecological modernisation theory. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A.; Elliott, R.J.R.; Shimamoto, K. Globalization, firm-level characteristics and environmental management: A study of Japan. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 59, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Johnson, R. Exporting Environmentalism: U.S. Multinational Chemical Corporations in Brazil and Mexico, 1st ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-262-57136-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, M.A.; Elliott, R.J.R.; Strobl, E. The environmental performance of firms: The role of foreign ownership, training, and experience. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardati, E.; Saygili, M. Multinationals and environmental regulation: Are foreign firms harmful? Environ. Dev. Econ. 2012, 17, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz, F.; Cole, M.A.; Elliott, R.J.R.; Ercolani, M.G. In Search of Environmental Spillovers. World Econ. 2009, 32, 136–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, G.; Tole, L. What is the environmental performance of firms overseas? An empirical investigation of the global gold mining industry. J. Prod. Anal. 2008, 30, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B. Green Development: Environment and Sustainability in a Developing World, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-415-39508-3. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Sarkis, J.; Wu, Z. Creating integrated business and environmental value within the context of China’s circular economy and ecological modernization. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokser-Liwerant, J. Globalization and Collective Identities. Soc. Compass 2002, 49, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jänicke, M. Ecological modernisation: New perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-S. Environmentalism in Developing Countries and the Case of a Large Korean City. Soc. Sci. Q. 1999, 80, 810–829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rootes, C. (Ed.) Environmental Movements: Local, National and Global; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-317-99483-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J.S. The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-19-969600-0. [Google Scholar]

- Spaargaren, G. Ecological modernization theory and the changing discourse on environment and modernity. In Environment and Global Modernity; Spaargaren, G., Mol, A.P.J., Buttel, F.H., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2000; pp. 41–71. ISBN 978-0-7619-6767-5. [Google Scholar]

- Brechin, S.R.; Kempton, W. Global environmentalism: A challenge to the postmaterialism thesis? Soc. Sci. Q. 1994, 75, 245–269. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; York, R. The globalization of environmental concern and the limits of the postmaterialist values explanation: Evidence from four multinational surveys. Sociol. Q. 2008, 49, 529–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement. In The Mexican-U.S. Free Trade Agreement; Garber, P., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Economic growth and the environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boli, J.; Thomas, G.M. World Culture in the World Polity: A Century of International Non-Governmental Organization. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1997, 62, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W. World Society, Institutional Theories, and the Actor. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 36, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Boli, J.; Thomas, G.M.; Ramirez, F.O. World Society and the Nation-State. Am. J. Sociol. 1997, 103, 144–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Frank, D.J.; Hironaka, A.; Schofer, E.; Tuma, N.B. The Structuring of a World Environmental Regime, 1870–1990. Int. Organ. 1997, 51, 623–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.J.; Hironaka, A.; Schofer, E. The nation-state and the natural environment over the twentieth century. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 65, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G.; Brown, J.W.; Chasek, P.S. Global Environmental Politics, 3rd ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-8133-6845-0. [Google Scholar]

- French, H.F. Vanishing Borders: Protecting the Planet in the Age of Globalization, 1st ed.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-393-32004-6. [Google Scholar]

- Schofer, E.; Hironaka, A. The Effects of World Society on Environmental Protection Outcomes. Soc. Forces 2005, 84, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wapner, P. Governance in Global Civil Society. In Global Governance; Young, O., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Baker, W.E. Modernization, Cultural Change, and the Persistence of Traditional Values. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 65, 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boli, J.; Thomas, G.M. Constructing World Culture: International Nongovernmental Organizations Since 1875; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Longhofer, W.; Schofer, E. National and Global Origins of Environmental Association. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 75, 505–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, A.K.; Dick, C.; Shandra, J.M. World Economy, World Society, and Environmental Harms in Less-Developed Countries. Sociol. Inq. 2011, 81, 53–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, P.; Thompson, G.; Bromley, S. Globalization in Question, 3rd ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-7456-9734-5. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R. Glocalization: Time-space and homogeneity-heterogeneity. In Global Modernities; Theory, Culture & Society; Featherstone, M., Lash, S., Robertson, R., Eds.; Sage: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 25–44. ISBN 0-8039-7947-9. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel, A. Unequal Exchange: A Study of the Imperialism of Trade, 1st ed.; Monthly Review Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 978-0-85345-188-4. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Alier, J. The Environmentalism of the Poor: A Study of Ecological Conflicts and Valuation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, J. Ecological Unequal Exchange: International Trade and Uneven Utilization of Environmental Space in the World System. Soc. Forces 2007, 85, 1369–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonds, E.; Downey, L. Green Technology and Ecologically Unequal Exchange: The Environmental and Social Consequences of Ecological Modernization in the World-System. J. World-Syst. Res. 2012, 18, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornborg, A. The Power of the Machine: Global Inequalities of Economy, Technology, and Environment; Altamira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-7591-1691-7. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, J. The Transnational Organization of Production and Uneven Environmental Degradation and Change in the World Economy. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2009, 50, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, S.G. Underdeveloping the Amazon: Extraction, Unequal Exchange, and the Failure of the Modern State, 1st ed.; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-226-08032-1. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson, A.K. The sociology of ecologically unequal exchange and carbon dioxide emissions, 1960–2005. Soc. Sci. Res. 2012, 41, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.O.; Lindroth, M. Ecologically unsustainable trade. Ecol. Econ. 2001, 37, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, R.S. The transfer of core-based hazardous production processes to the export processing zones of the periphery: The maquiladora centers of northern Mexico. J. World-Syst. Res. 2003, 9, 317–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, B.A.; Taylor, M.S. North-South trade and the environment. Q. J. Econ. 1994, 109, 755–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, J.; Grether, J.-M. Globalization and Dirty Industries: Do Pollution Havens Matter? In Challenges to Globalization: Analyzing the Economics; Baldwin, R.E., Winters, L.A., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004; pp. 167–205. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.J.; Caldeira, K.; Matthews, H.D. Future CO2 Emissions and Climate Change from Existing Energy Infrastructure. Science 2010, 329, 1330–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvergne, P. Globalization and the Environment. In Global Political Economy; Ravenhill, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 450–480. [Google Scholar]

- Linnér, B.-O.; Jacob, M. From Stockholm to Kyoto and beyond: A review of the globalization of global warming policy and North–South relations. Globalizations 2005, 2, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. Environmental mega-conferences—From Stockholm to Johannesburg and beyond. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2003, 13, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E. Globalization and Its Discontents, 1st ed.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-393-32439-6. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.T. Predicting Participation in Environmental Treaties: A World-System Analysis. Sociol. Inq. 1996, 66, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.T. Global Inequality and Climate Change. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2001, 14, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.T. Trouble in Paradise: Globalization and Environmental Crises in Latin America; Routledge: London, UK; Armonk, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.T.; Parks, B.C.; Vásquez, A.A. Who Ratifies Environmental Treaties and Why? Institutionalism, Structuralism and Participation by 192 Nations in 22 Treaties. Glob. Environ. Politics 2004, 4, 22–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.T.; Grimes, P.E. World-system theory and the environment: Toward a new synthesis. In Sociological Theory and the Environment: Classical Foundations, Contemporary Insights; Dunlap, R.E., Ed.; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.: Lanham, MD, USA, 2002; pp. 167–196. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.T.; Parks, B.C. Fueling Injustice: Globalization, Ecologically Unequal Exchange and Climate Change. Globalizations 2007, 4, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornborg, A. Zero-sum world challenges in conceptualizing environmental load displacement and ecologically unequal exchange in the world-system. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2009, 50, 237–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. The Local and the Global: Globalization and Ethnicity. In Culture, Globalization and the World System: Contemporary Conditions for the Representation of Identity; King, A.D., Ed.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1991; pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, B.; Geschiere, P. (Eds.) Globalization and Identity: Dialectics of Flow and Closure; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 1999; ISBN 0-631-21238-8. [Google Scholar]

- Devine-Wright, P. Think global, act local? The relevance of place attachments and place identities in a climate changed world. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Globalization and Territorial Identification: A Multilevel Analysis across 50 Countries. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2016, 28, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Prothero, A. Green consumption: Life-politics, risk and contradictions. J. Consum. Cult. 2008, 8, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Brady, D.; Beckfield, J.; Zhao, W. The Consequences of Economic Globalization for Affluent Democracies. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2007, 33, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.I. Globalization and the sociology of Immanuel Wallerstein: A critical appraisal. Int. Sociol. 2011, 26, 723–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmaklı, A.D.; Boone, C.; van Witteloostuijn, A. When Does Globalization Lead to Local Adaptation? The Emergence of Hybrid Islamic Schools in Turkey, 1985–2007. Am. J. Sociol. 2017, 122, 1822–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Koster, F. Globalization, Social Structure, and the Willingness to Help Others: A Multilevel Analysis Across 26 Countries. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2007, 23, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kunovich, R.M. The Sources and Consequences of National Identification. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 74, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, S. Does Globalization Render People More Ethnocentric? Globalization and People’s Views on Cultures. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2012, 71, 436–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essary, E.H. Speaking of Globalization: Frame Analysis and the World Society. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2007, 48, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewes, J.; Mau, S. Globalization, socio-economic status and welfare chauvinism: European perspectives on attitudes toward the exclusion of immigrants. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2013, 54, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, F. Cosmopolitanism in a global perspective: An international comparison of open-minded orientations and identity in relation to globalization. Int. Sociol. 2012, 27, 21–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, P.; Lim, G.C.; Buang, A.A. Globalization Measurement: Notes on Common Globalization Indexes. Knowl. Manag. Econ. Inf. Technol. 2011, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson, A.K. The Effects of Primary Sector Foreign Investment on Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Agriculture Production in Less-Developed Countries, 1980–99. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2007, 48, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, A.K.; Clark, B. Are the Economy and the Environment Decoupling? A Comparative International Study, 1960–2005. Am. J. Sociol. 2012, 118, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, K.W. Temporal variation in the relationship between environmental demands and well-being: A panel analysis of developed and less-developed countries. Popul. Environ. 2014, 36, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, K.W.; Schor, J.B. Economic Growth and Climate Change: A Cross-National Analysis of Territorial and Consumption-Based Carbon Emissions in High-Income Countries. Sustainability 2014, 6, 3722–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, M.T. Urbanization and the Natural Environment: An Environmental Sociological Review and Synthesis. Organ. Environ. 2010, 23, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, A.K.; Auerbach, D.; Clark, B. The (De-) carbonization of urbanization, 1960–2010. Clim. Chang. 2014, 127, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcotullio, P.J.; Hughes, S.; Sarzynski, A.; Pincetl, S.; Sanchez Peña, L.; Romero-Lankao, P.; Runfola, D.; Seto, K.C. Urbanization and the carbon cycle: Contributions from social science. Earths Future 2014, 2, 496–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, R.; Rosa, E.A.; Dietz, T. Footprints on the Earth: The Environmental Consequences of Modernity. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2003, 68, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, A.K.; Givens, J. The Changing Effect of Economic Development on the Consumption-Based Carbon Intensity of Well-Being, 1990–2008. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, R. Structural Influences on Energy Production in South and East Asia, 1971–2002. Sociol. Forum 2007, 22, 532–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C. Analysis of Panel Data, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, A.; Urpelainen, J. How do Competing Interest Groups Influence Environmental Policy? The Case of Renewable Electricity in Industrialized Democracies, 1989–2007. Polit Stud. 2013, 61, 874–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, R.; Rosa, E.A. Choking on Modernity: A Human Ecology of Air Pollution. Soc. Probl. 2012, 59, 282–300. [Google Scholar]

- Canadell, J.G.; Quéré, C.L.; Raupach, M.R.; Field, C.B.; Buitenhuis, E.T.; Ciais, P.; Conway, T.J.; Gillett, N.P.; Houghton, R.A.; Marland, G. Contributions to accelerating atmospheric CO2 growth from economic activity, carbon intensity, and efficiency of natural sinks. PNAS 2007, 104, 18866–18870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H. Globalization, Consumerism, and the Emergence of Teens in Contemporary Vietnam. J. Soc. Hist. 2015, 49, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, P.N. Consumerism in World History: The Global Transformation of Desire; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-0-203-18323-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wilk, R. Consumption, human needs, and global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2002, 12, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, H.; Meier, L. The New Middle Classes: Globalizing Lifestyles, Consumerism and Environmental Concern; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4020-9938-0. [Google Scholar]

- Caselli, M. Some Reflections on Globalization, Development and the Less Developed Countries; Centre for the Study of Globalisation and Regionalisation, University of Warwick: Coventry, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson, A.K. Environment, Development, and Ecologically Unequal Exchange. Sustainability 2016, 8, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, A.K.; Clark, B. The Economy, Military, and Ecologically Unequal Exchange Relationships in Comparative Perspective: A Panel Study of the Ecological Footprints of Nations, 1975–2000. Soc. Probl. 2009, 56, 621–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Countries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania (8) | Chile (10) | Guyana (10) | Moldova (5) | Singapore (10) |

| Angola (5) | Colombia (10) | Honduras (10) | Mongolia (7) | Slovak Republic (5) |

| Argentina (10) | Congo, Dem. Rep. (5) | Hungary (5) | Morocco (8) | Slovenia (5) |

| Australia (6) | Congo, Rep. (10) | India (10) | Mozambique (5) | South Africa (10) |

| Austria (8) | Costa Rica (10) | Indonesia (7) | Namibia (6) | Spain (5) |

| Azerbaijan (5) | Cote d’Ivoire (10) | Iran, Islamic Rep. (8) | Nepal (10) | Sudan (7) |

| Bahamas (7) | Croatia (5) | Iraq (10) | Netherlands (10) | Suriname (8) |

| Bangladesh (9) | Cyprus (5) | Ireland (5) | New Zealand (7) | Swaziland (10) |

| Barbados (9) | Czech Republic (5) | Israel (5) | Nicaragua (5) | Sweden (8) |

| Belarus (5) | Denmark (10) | Italy (6) | Niger (10) | Switzerland (5) |

| Belgium (5) | Dominican Republic (10) | Japan (5) | Nigeria (7) | Tajikistan (5) |

| Belize (6) | Ecuador (10) | Jordan (9) | Norway (10) | Tanzania (6) |

| Benin (10) | Egypt, Arab Rep. (10) | Kazakhstan (5) | Oman (5) | Thailand (5) |

| Bhutan (8) | El Salvador (10) | Kiribati (8) | Pakistan (10) | Togo (10) |

| Bolivia (10) | Estonia (5) | Korea, Rep. (10) | Panama (10) | Trinidad and Tobago (9) |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina (5) | Ethiopia (7) | Kyrgyz Republic (5) | Paraguay (10) | Tunisia (9) |

| Botswana (9) | Fiji (10) | Lao PDR (6) | Peru (7) | Turkey (10) |

| Brazil (10) | Finland (9) | Latvia (5) | Philippines (10) | Uganda (7) |

| Brunei Darussalam (7) | France (10) | Lebanon (5) | Poland (5) | Ukraine (5) |

| Bulgaria (8) | Gabon (10) | Lesotho (6) | Portugal (5) | United Arab Emirates (9) |

| Burkina Faso (10) | Gambia (10) | Macedonia, FYR (5) | Romania (6) | United Kingdom (6) |

| Burundi (10) | Germany (5) | Madagascar (10) | Russian Federation (5) | Uruguay (7) |

| Cabo Verde (8) | Ghana (7) | Malawi (10) | Rwanda (10) | Venezuela, RB (10) |

| Cambodia (5) | Greece (5) | Malaysia (6) | Saudi Arabia (10) | Vietnam (6) |

| Cameroon (10) | Guatemala (10) | Mali (10) | Senegal (8) | Yemen, Rep. (5) |

| Central African Republic (10) | Guinea (6) | Malta (9) | Seychelles (7) | Zambia (7) |

| Chad (10) | Guinea-Bissau (9) | Mauritania (10) | Sierra Leone (10) | Zimbabwe (8) |

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 emissions per capita (metric tons) | 3.73 | 5.05 | 0.02 | 56.05 |

| KOF index of globalization | 49.20 | 18.65 | 12.75 | 92.81 |

| KOF index of economic globalization | 51.09 | 19.77 | 8.73 | 97.74 |

| KOF index of political globalization | 58.02 | 22.78 | 3.73 | 98.30 |

| KOF index of social and cultural globalization | 40.71 | 22.51 | 6.70 | 93.25 |

| Developed countries | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| GDP per capita (constant 2005 US$) | 7802.49 | 12,424.20 | 127.50 | 81,947.24 |

| Urbanization (% Population) | 51.22 | 23.18 | 2.85 | 100.00 |

| Service sector (% of GDP) | 48.67 | 11.86 | 10.57 | 82.17 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCSE a | DK b | |||

| Globalization | −0.081 *** | (0.017) | −0.069 * | (0.033) |

| Globalization × 1975 | 0.004 | (0.014) | 0.002 | (0.004) |

| Globalization × 1980 | 0.019 | (0.024) | 0.023 ** | (0.008) |

| Globalization × 1985 | 0.001 | (0.031) | 0.006 | (0.012) |

| Globalization × 1990 | 0.038 | (0.036) | 0.026 * | (0.013) |

| Globalization × 1995 | 0.090 *** | (0.024) | 0.110 *** | (0.014) |

| Globalization × 2000 | 0.100 *** | (0.027) | 0.125 *** | (0.017) |

| Globalization × 2005 | 0.179 *** | (0.029) | 0.196 *** | (0.026) |

| Globalization × 2010 | 0.239 *** | (0.038) | 0.255 *** | (0.024) |

| Globalization × 2014 | 0.198 *** | (0.036) | 0.210 *** | (0.023) |

| DCs | −4.579 *** | (0.616) | −4.879 *** | (0.388) |

| Globalization × DCs | 1.308 *** | (0.171) | 1.383 *** | (0.106) |

| Globalization × DCs × 1975 | −0.662 *** | (0.165) | −0.814 *** | (0.094) |

| Globalization × DCs × 1980 | −0.773 ** | (0.236) | −0.908 *** | (0.074) |

| Globalization × DCs × 1985 | −0.746 *** | (0.219) | −0.924 *** | (0.090) |

| Globalization × DCs × 1990 | −1.351 *** | (0.240) | −1.526 *** | (0.097) |

| Globalization × DCs × 1995 | −1.182 *** | (0.185) | −1.409 *** | (0.079) |

| Globalization × DCs × 2000 | −1.226 *** | (0.191) | −1.415 *** | (0.095) |

| Globalization × DCs × 2005 | −1.295 *** | (0.195) | −1.482 *** | (0.109) |

| Globalization × DCs × 2010 | −1.764 *** | (0.251) | −2.073 *** | (0.078) |

| Globalization × DCs × 2014 | −1.972 *** | (0.180) | −2.105 *** | (0.076) |

| GDP per capita | 0.205 *** | (0.020) | 0.214 *** | (0.030) |

| Urbanization | 0.058 * | (0.028) | 0.056 + | (0.033) |

| Service sector | −0.012 | (0.022) | −0.021 | (0.027) |

| DCs × year dummies | Included | Included | ||

| Country dummies | Included | Included | ||

| Year dummies | Included | Included | ||

| Constant | −0.704 *** | (0.143) | −0.779 *** | (0.201) |

| R-squared | 0.965 | 0.978 | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCSE a | DK b | |||

| EG | −0.040 *** | (0.010) | −0.024 | (0.017) |

| EG × 1975 | −0.020 * | (0.008) | −0.024 *** | (0.004) |

| EG × 1980 | −0.009 | (0.013) | −0.015 *** | (0.005) |

| EG × 1985 | −0.020 | (0.012) | −0.019 ** | (0.006) |

| EG × 1990 | −0.005 | (0.015) | −0.016 + | (0.009) |

| EG × 1995 | 0.025 ** | (0.009) | 0.026 *** | (0.005) |

| EG × 2000 | 0.027 + | (0.014) | 0.055 ** | (0.017) |

| EG × 2005 | 0.118 *** | (0.023) | 0.150 *** | (0.019) |

| EG × 2010 | 0.130 *** | (0.027) | 0.155 *** | (0.011) |

| EG × 2014 | 0.121 *** | (0.023) | 0.137 *** | (0.014) |

| DCs | 0.716 | (1.898) | 1.361 * | (0.602) |

| EG × DCs | −0.090 | (0.492) | −0.252 | (0.166) |

| EG × DCs × 1975 | 0.427 | (0.501) | 0.533 *** | (0.086) |

| EG × DCs × 1980 | 0.119 | (0.547) | 0.261 * | (0.115) |

| EG × DCs × 1985 | 0.306 | (0.530) | 0.412 * | (0.178) |

| EG × DCs × 1990 | 0.051 | (0.506) | 0.162 | (0.167) |

| EG × DCs × 1995 | 0.177 | (0.500) | 0.233 | (0.173) |

| EG × DCs × 2000 | 0.191 | (0.497) | 0.251 | (0.183) |

| EG × DCs × 2005 | 0.016 | (0.503) | −0.015 | (0.222) |

| EG × DCs × 2010 | −0.008 | (0.499) | −0.081 | (0.193) |

| EG × DCs × 2014 | −0.210 | (0.494) | −0.133 | (0.133) |

| SCG | 0.025 | (0.017) | 0.042 ** | (0.014) |

| PG | 0.011 | (0.019) | −0.005 | (0.026) |

| GDP per capita | 0.200 *** | (0.020) | 0.205 *** | (0.027) |

| Urbanization | 0.018 | (0.027) | 0.018 | (0.034) |

| Service sector | −0.014 | (0.022) | −0.015 | (0.025) |

| DCs × year dummies | Included | Included | ||

| Country dummies | Included | Included | ||

| Year dummies | Included | Included | ||

| Constant | −0.747 *** | (0.146) | −0.832 *** | (0.195) |

| R-squared | 0.962 | 0.977 | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCSE a | DK b | |||

| PG | −0.112 ** | (0.039) | −0.144 *** | (0.040) |

| PG × 1975 | 0.079 + | (0.045) | 0.087 *** | (0.021) |

| PG × 1980 | 0.099 * | (0.047) | 0.116 ** | (0.040) |

| PG × 1985 | 0.104 * | (0.043) | 0.116 ** | (0.037) |

| PG × 1990 | 0.091 * | (0.043) | 0.117 ** | (0.037) |

| PG × 1995 | 0.071 | (0.045) | 0.096 * | (0.047) |

| PG × 2000 | 0.065 | (0.047) | 0.082 + | (0.043) |

| PG × 2005 | 0.057 | (0.050) | 0.057 | (0.047) |

| PG × 2010 | 0.082 | (0.053) | 0.087+ | (0.047) |

| PG × 2014 | 0.043 | (0.053) | 0.039 | (0.048) |

| DCs | −1.275 ** | (0.405) | −1.672 *** | (0.263) |

| PG × DCs | 0.427 *** | (0.102) | 0.535 *** | (0.064) |

| PG × DCs × 1975 | −0.381 *** | (0.114) | −0.486 *** | (0.064) |

| PG × DCs × 1980 | −0.203 | (0.157) | −0.341 *** | (0.089) |

| PG × DCs × 1985 | −0.223 * | (0.098) | −0.334 *** | (0.062) |

| PG × DCs × 1990 | −0.456 *** | (0.113) | −0.593 *** | (0.072) |

| PG × DCs × 1995 | −0.254 * | (0.125) | −0.383 *** | (0.083) |

| PG × DCs × 2000 | −0.247 * | (0.120) | −0.372 *** | (0.067) |

| PG × DCs × 2005 | −0.159 | (0.131) | −0.232 ** | (0.080) |

| PG × DCs × 2010 | −0.516 *** | (0.145) | −0.702 *** | (0.063) |

| PG × DCs × 2014 | −0.650 *** | (0.136) | −0.722 *** | (0.089) |

| EG | −0.034 ** | (0.011) | −0.032 * | (0.013) |

| SCG | 0.010 | (0.017) | 0.023 + | (0.014) |

| GDP per capita | 0.209 *** | (0.022) | 0.219 *** | (0.028) |

| Urbanization | 0.002 | (0.031) | −0.008 | (0.032) |

| Service sector | −0.016 | (0.023) | −0.020 | (0.026) |

| DCs × year dummies | Included | Included | ||

| Country dummies | Included | Included | ||

| Year dummies | Included | Included | ||

| Constant | −0.322 | (0.202) | −0.294 | (0.277) |

| R-squared | 0.963 | 0.977 | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCSE a | DK b | |||

| SCG | −0.029 | (0.022) | −0.007 | (0.015) |

| SCG× 1975 | 0.011 | (0.016) | 0.010 * | (0.004) |

| SCG× 1980 | 0.030 | (0.024) | 0.025 ** | (0.009) |

| SCG× 1985 | 0.016 | (0.028) | 0.008 | (0.014) |

| SCG× 1990 | 0.052 + | (0.027) | 0.033 * | (0.014) |

| SCG× 1995 | 0.074 *** | (0.021) | 0.075 *** | (0.007) |

| SCG× 2000 | 0.105 *** | (0.023) | 0.114 *** | (0.008) |

| SCG× 2005 | 0.159 *** | (0.026) | 0.167 *** | (0.011) |

| SCG× 2010 | 0.184 *** | (0.029) | 0.185 *** | (0.012) |

| SCG× 2014 | 0.167 *** | (0.028) | 0.170 *** | (0.008) |

| DCs | −3.641 *** | (0.921) | −3.942 *** | (0.559) |

| SCG× DCs | 1.055 *** | (0.263) | 1.135 *** | (0.154) |

| SCG× DCs × 1975 | −0.559* | (0.241) | −0.584 *** | (0.071) |

| SCG× DCs × 1980 | −0.999 *** | (0.288) | −1.032 *** | (0.094) |

| SCG× DCs × 1985 | −0.983** | (0.324) | −0.980 *** | (0.089) |

| SCG× DCs × 1990 | −0.968** | (0.363) | −1.057 *** | (0.167) |

| SCG× DCs × 1995 | −1.130 *** | (0.299) | −1.353 *** | (0.150) |

| SCG× DCs × 2000 | −1.236 *** | (0.304) | −1.422 *** | (0.164) |

| SCG× DCs × 2005 | −1.505 *** | (0.305) | −1.740 *** | (0.182) |

| SCG× DCs × 2010 | −1.834 *** | (0.355) | −2.115 *** | (0.140) |

| SCG× DCs × 2014 | −1.868 *** | (0.280) | −1.970 *** | (0.128) |

| EG | −0.017 + | (0.010) | −0.011 | (0.020) |

| PG | 0.003 | (0.019) | −0.013 | (0.026) |

| GDP per capita | 0.196 *** | (0.019) | 0.203 *** | (0.028) |

| Urbanization | 0.042 | (0.030) | 0.042 | (0.033) |

| Service sector | −0.020 | (0.024) | −0.033 | (0.026) |

| DCs × year dummies | Included | Included | ||

| Country dummies | Included | Included | ||

| Year dummies | Included | Included | ||

| Constant | −0.672 *** | (0.124) | −0.717 *** | (0.174) |

| R-squared | 0.966 | 0.978 | ||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Chen, H.; Rong, Z. Environmental Homogenization or Heterogenization? The Effects of Globalization on Carbon Dioxide Emissions, 1970–2014. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2752. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102752

Wang Y, Zhou T, Chen H, Rong Z. Environmental Homogenization or Heterogenization? The Effects of Globalization on Carbon Dioxide Emissions, 1970–2014. Sustainability. 2019; 11(10):2752. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102752

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yan, Tao Zhou, Hao Chen, and Zhihai Rong. 2019. "Environmental Homogenization or Heterogenization? The Effects of Globalization on Carbon Dioxide Emissions, 1970–2014" Sustainability 11, no. 10: 2752. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102752

APA StyleWang, Y., Zhou, T., Chen, H., & Rong, Z. (2019). Environmental Homogenization or Heterogenization? The Effects of Globalization on Carbon Dioxide Emissions, 1970–2014. Sustainability, 11(10), 2752. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102752