Interactions Among Factors Influencing Product Innovation and Innovation Behaviour: Market Orientation, Managerial Ties, and Government Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

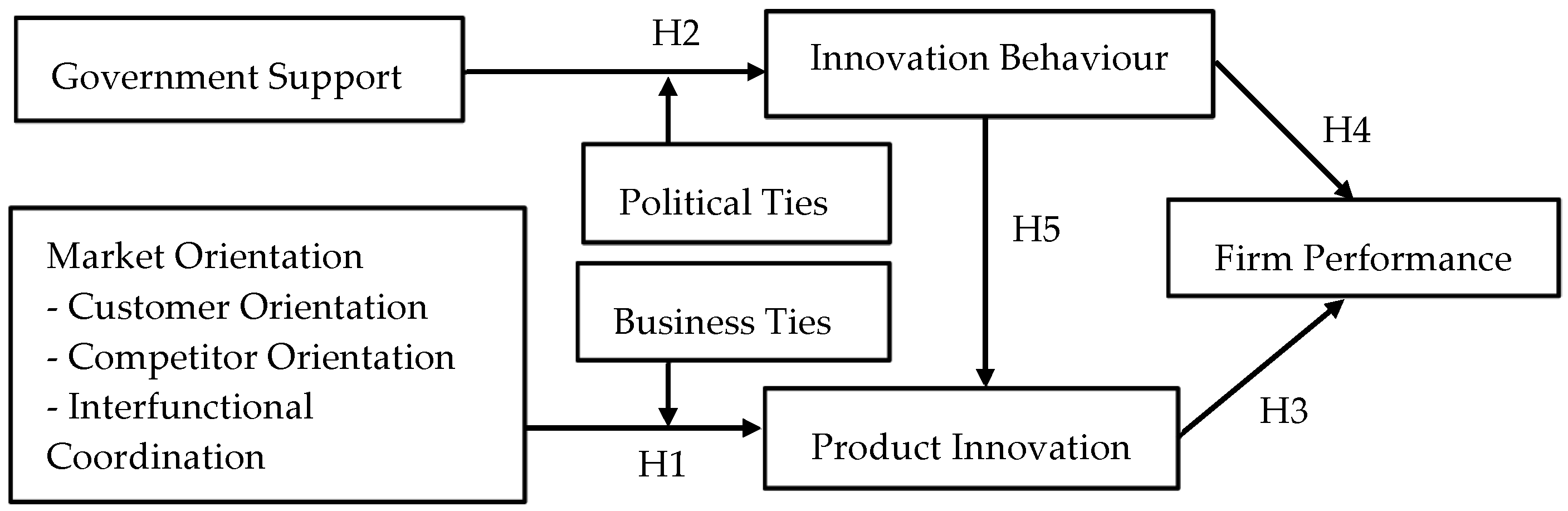

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Resource-Based View and Sustainable Innovation

2.2. Market Orientation

2.3. Managerial Ties

2.4. Market Orientation, Business Ties, and Product Innovation

2.5. Government Support, Political Ties, and Innovation Behaviour

2.6. Market Orientation, Product Innovation, and Firm Performance

2.7. Government Support, Innovation Behaviour, and Firm Performance

2.8. Government Support, Innovation Behaviour, and Product Innovation

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Characteristics

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.3. Structural Equation Models and Relationship Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs and Scale Items | FL | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market orientation | |||

| Consumer orientation (alpha = 0.93) | 0.93 | 0.66 | |

| 1. Customer satisfaction is the primary goal of firms. | 0.98 | ||

| 2. Our strategies focus on creating superior value for customers. | 0.96 | ||

| 3. Our strategies emphasize the understanding of customer needs. | 0.50 | ||

| 4. Customer complaints and suggestions are considered essential by our firm. | 0.66 | ||

| 5. Our firm has the means to frequently measure customer satisfaction. | 0.82 | ||

| 6. We regularly analyse factors that influence the purchasing behaviour of customers. | 0.80 | ||

| 7. We have diligently traced our customers after the sale. | 0.86 | ||

| Competitor orientation (alpha = 0.92) | 0.92 | 0.74 | |

| 1. Our firm has shared information among departments regarding competitors’ strategies. | 0.95 | ||

| 2. We emphasize fast responses to competitor actions that threaten us. | 0.79 | ||

| 3. Our firm has frequent meetings to discuss the strengths and strategies of competitors. | 0.96 | ||

| 4. We seek to anticipate the behaviour of our competitors. | 0.72 | ||

| Interfunctional coordination (alpha = 0.95) | 0.95 | 0.72 | |

| 1. We often communicate information about customer needs across all firm sections. | 0.70 | ||

| 2. We regularly discuss market trends across all firm sections. | 0.88 | ||

| 3. There is continual communication between departments and functions in our firm. | 0.77 | ||

| 4. Interdepartmental knowledge exchange on specific topics takes place in systematic meetings. | 0.89 | ||

| 5. Our firm distributes information on creative approaches to innovations to all firm sections. | 0.93 | ||

| 6. Discussions about our strategies occur between departments to enhance short-term and long-term goals to achieve better performance. | 0.97 | ||

| 7. Our firm continually seeks out opportunities that provide a competitive advantage. | 0.67 | ||

| Managerial ties | |||

| Business ties (alpha = 0.71) | 0.75 | 0.51 | |

| The owners have been diligently using personal ties, networks, and connections with | |||

| 1. Customers. | 0.51 | ||

| 2. Suppliers. | 0.80 | ||

| 3. Competitors. | 0.80 | ||

| Political ties (alpha = 0.89) | 0.89 | 0.73 | |

| The owners have been diligently using personal ties, networks, and connections with | |||

| 1. Political leaders in various levels of the government. | 0.81 | ||

| 2. Officials in industrial bureaus. | 0.85 | ||

| 3. Officials in regulatory and supporting organizations such as tax bureaus, state banks, commercial administration bureaus, and the like. | 0.90 | ||

| Innovation behaviour (alpha = 0.88) | 0.91 | 0.58 | |

| 1. Our personnel frequently seek out new ways to improve and develop products and services. | 0.85 | ||

| 2. Our personnel often suggest creative ideas for unique products and services. | 0.87 | ||

| 3. Our personnel have an action plan for developing new ideas. | 0.80 | ||

| 4. Our personnel are active in finding knowledge to develop skills and work behaviour in terms of innovation. | 0.87 | ||

| Product innovation (alpha = 0.94) | 0.94 | 0.77 | |

| 1. Customers have perceived that our products are unique and different. | 0.93 | ||

| 2. Compared to competitors’ products and services, our new products and services often provide superior value for customers. | 0.93 | ||

| 3. We promptly respond to customer demands and develop new products and services. | 0.97 | ||

| 4. We continuously improve primary products and services and inject creativity into new products. | 0.73 | ||

| 5. Our firm develops new products from ideas, suggestions, or complaints that come from customers or suppliers. | 0.80 | ||

| Government support (alpha = 0.93) | 0.95 | 0.80 | |

| 1. Provided policies and programs that have been beneficial to firm performance. | 0.98 | ||

| 2. Provided needed knowledge and other technical support. | 0.94 | ||

| 3. Provided important market information. | 0.77 | ||

| 4. Provided external funding and financing. | 0.86 | ||

| 5. Provided information about essential regulations and helped firms obtain copyright or patent and access to rare resources. | 0.91 | ||

| Firm performance (alpha = 0.91) | 0.94 | 0.76 | |

| 1. Sales growth. | 0.94 | ||

| 2. Return on investment. | 0.85 | ||

| 3. Market share. | 0.75 | ||

| 4. Consumer satisfaction. | 0.95 | ||

| 5. Consumer loyalty. | 0.86 |

References

- Porter, M.E. How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979; Volume 57, p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nation: With a New Introduction; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Triznova, M.; Maťova, H.; Dvoracek, J.; Sadek, S. Customer relationship management based on employees and corporate culture. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 26, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, F.; Eren, E. Organizational learning capacity impact on sustainable innovation: The case of public hospitals. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 181, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, J.; Cunningham, S. Four models of the creative industries. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2008, 14, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Hsieh, C.J. A research in relating entrepreneurship, marketing capability, innovative capability and sustained competitive advantage. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.C.; Tein, S.W.; Lee, H.M. Social capital, creativity, and new product advantage: An empirical study. Int. J. Electron. Bus. Manag. 2010, 8, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sulistyo, H.; Siyamtinah. Innovation capability of SMEs through entrepreneurship, marketing capability, relational capital and empowerment. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2016, 21, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, R. Innovating for sustainability: A framework for sustainable innovations and a model of sustainable innovations orientation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 14–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgaard-Park, S.M.; Dahlgaard, J.J. A strategy for building sustainable innovation excellence—A Danish study. In Corporate Sustainability as a Challenge for Comprehensive Management; Zink, K.J., Ed.; Physica-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawali, S. Creative industries. In For Quality People; TPA Publishing: Bangkok, Thailand, 2010; pp. 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Adeniran, T.V.; Johnston, K.A. Investigation the dynamic capabilities and competitive advantage of South African SMEs. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 4088–4099. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, W.R.; Nanda, R. Financing constraints and entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Research on Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Audrestsch, A., Falck, O., Heblich, S., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011; pp. 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Maeseneire, W.D.; Claeys, T. SMEs, foreign direct investment and financial constraints: The case of Belgium. Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 21, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waari, D.N.; Mwangi, W.M. Factors influencing access to finance by micro, small and medium enterprises in Meru county, Kenya. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2015, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nijssen, E.J.; Frambach, R.T. Determinants of the adoption of new product development tools by industrial firms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2000, 29, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Carnes, C.M.; Xu, K. A current view of resource-based theory in operations management: A response to Bromiley and Rau. J. Oper. Manag. 2016, 41, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örnek, A.S.; Ayas, S. The relationship between intellectual capital, innovative work behavior and business performance reflection. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todericiu, R.; Stăniț, A. Intellectual capital—The key for sustainable competitive advantage for the SME’s sector. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 27, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, G.; Yilmaz, C. Innovative capability, innovation strategy and market orientation: An empirical analysis in the Turkish software industry. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2008, 12, 69–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, L. The effects of market orientation on product innovation. Econ. Trends Econ. Policy 2006, 107, 46–65. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L.; Chung, H.F.L. The moderating role of managerial ties in market orientation and innovation: An Asian perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2431–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Pawar, K.S. Effects of business and political ties on product innovation performance: Evidence from China and India. Technovation 2018, 80–81, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J.; Hansen, E.G. Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.; Wright, M.; David, J.; Ketchen, J. The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Slater, S.F. Toward greater understanding of market orientation and the resource-based view. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, J.C.; Slater, S.F. The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. J. Mark. Res. 1990, 54, 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Šályová, S.; Táborecká-Petrovičováa, J.; Nedelová, G.; Ďaďo, J. Effect of marketing orientation on business performance: A study from Slovak foodstuff industry. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 34, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi-Tavani, S.; Sharifi, H.; Najafi-Tavani, Z. Market orientation, marketing capability, and new product performance: The moderating role of absorptive capacity. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5059–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Slater, S.F. Market orientation and performance: An integration of disparate approaches. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpandé, R.; Farley, J.U.; Frederick, E.; Webster, J. Orientation, and innovativeness in Japanese firms: A quadrad analysis. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatigon, H.; Xuereb, J.M. Strategic orientation of the firm and new product performance. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.K.; Kim, N.; Srivastava, R.K. Market orientation and organizational performance: Is innovation a missing link? J. Mark. 1998, 62, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidor, A.; Gelmereanu, C.; Baru, P.; Morar, L. Diagnosing organizational culture for SME performance. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2012, 3, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evens, T.; Donders, K. Mergers and acquisitions in TV broadcasting and distribution: Challenges for competition, industrial and media policy. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, J.R.; Brennan, M.; McAdam, R. A rewarding experience? Exploring how crowdfunding is affecting music industry business models. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, K.O.; Latif, H.; Sariisik, M.; Ergun, O. International competitive advantage of Turkish tourism industry: A comparative analysis of Turkey and Spain by using the Diamond model of M. Porter. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 1064–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhao, W.; Watanabe, C.; Griffy-Brown, C. Competitive advantage in an industry cluster: The case of Dalian Software Park in China. Technol. Soc. 2009, 31, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, U.; Gu, X. Creative industry clusters in Shanghai: A success story? Int. J. Cult. Policy 2012, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Luo, Y. Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 486–501. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, P.; Liang, Q.; Liu, H.; Hou, M. The moderating role of context in managerial ties–firm performance link: A meta-analytic review of mainly Chinese-based studies. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2013, 19, 461–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, S.; Zhou, K.Z.; Li, J.J. The effects of business and political ties on firm performance: Evidence from China. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Hsu, M.K.; Liu, S.S. The moderating role of institutional networking in the customer orientation–trust/commitment–performance causal chain in China. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.; Shulman, A.D. Competitive advantage in public-sector organizations: Explaining the public good/sustainable competitive advantage paradox. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Wright, M. The future of resource-based theory: Revitalization or decline? J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, J.P.J.; Fris, P.; Stam, E. Creative Industries: Heterogeneity and Connection with Regional Firm Entry; EIM Business and Policy Research: Zoetermeer, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kamboj, S.; Goyal, P.; Rahman, Z. A resource-based view on marketing capability, operations capability and financial performance: An empirical examination of mediating role. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 189, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahy, J. A resource-based analysis of sustainable competitive advantage in a global environment. Int. Bus. Rev. 2002, 11, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, M.J.; Osman, I.; Alhabshi, S.M. Effect of intellectual capital on organizational performance. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogan, L.M.; Artene, A.; Sarca, I. The impact of intellectual capital on organizational performance. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 221, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H. The relationships among intellectual capital, social capital, and performance—The moderating role of business ties and environmental uncertainty. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Bossink, B.; van Vliet, M. Dynamic capabilities and organizational routines for managing innovation towards sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distanont, A.; Khongmalai, O. The role of innovation in creating a competitive advantage. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkan, A.; Bozkurt, O.; Arman, M. The impacts of intellectual capital, innovation and organizational strategy on firm performance. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncoro, W.; Suriani, W.O. Achieving sustainable competitive advantage through product innovation and market driving. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2018, 23, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, C.T.; Rasli, A. The relationship between innovative work behavior on work role performance: An empirical study. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 129, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, J.P.J.; Hartog, D.N.D. Measuring innovative work behaviour. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2010, 19, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starovic, D.; Marr, B. Understanding Corporate Value: Managing and Reporting Intellectual Capital; Chartered Institute of Management Accountants: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hana, U. Competitive advantage achievement through innovation and knowledge. J. Compet. 2013, 5, 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dögl, C.; Holtbrügge, D.; Schuster, T. Competitive advantage of German renewable energy firms in India and China. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2012, 7, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomášková, I.E. The current methods of measurement of market orientation. Eur. Res. Stud. 2009, 10, 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Li, J.J.; Zhou, N.; Su, C. Market orientation, job satisfaction, product quality, and firm performance: Evidence from China. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 985–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Zhou, K.Z. How foreign firms achieve competitive advantage in the Chinese emerging economy: Managerial ties and market orientation. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, A.K.; Jawoeski, B.J. Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial Implications. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadcroft, P.; Jarratt, D. Market Orientation: An iterative process of customer and market engagement. J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 2007, 14, 21–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kull, A.J.; Mena, J.A.; Korschun, D. A resource-based view of stakeholder marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5553–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmelin, H.; Seuring, S. Determinants of a sustainable new product development. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 69, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muda, S.; Rahman, M.R.C.A. Human capital in SMEs life cycle perspective. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 35, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, R.J.B.; Kim, D.; Bello, D.C. Relationship-based product innovations: Evidence from the global supply chain. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omerzel, D.G.; Jurdana, D.S. The influence of intellectual capital on innovativeness and growth in tourism SMEs: Empirical evidence from Slovenia and Croatia. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraz. 2016, 29, 1075–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Mashahadi, F.; Ahmad, N.H.; Mohamad, O. Market orientation and innovation ambidexterity: A synthesized model for internationally operated herbal-based small and medium enterprises (HbSMEs). Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geletkanycz, M.A.; Hambrick, D.C. The external ties of top executives: Implications for strategic choice and performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 654–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözbilir, F. The interaction between social capital, creativity, and efficiency in organizations. Think. Skills Creat. 2018, 27, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J. Competitiveness Analysis for China’s biopharmaceutical industry based on Porter Diamond Mode. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2014, 6, 477–485. [Google Scholar]

- Hofman, P.S.; Bruij, T.D. The emergence of sustainable innovations: Key factors and regional support Structures. In Facilitating Sustainable Innovation through Collaboration; Sarkis, J., Cordeiro, J.J., Brust, D.V., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, R.H.; Hillman, A.; Zardkoohi, A.; Cannella, A.A. Former government officials as outside directors: The role of human and social capital. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoza, G.; Fornes, G.; Farber, V.; Duarte, R.G.; Gutierrez, J.R. Barriers and public policies affecting the international expansion of Latin American SMEs: Evidence from Brazil, Colombia, and Peru. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2030–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurse, K.; Ye, Z. Creative Industries for Youth: Unleashing Potential and Growth; Vienna International Centre: Wien, Austria, 2013; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Boccella, N.; Salerno, I. Creative economy, cultural industries and local development. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.C.; Pizá, M.; Gómez, F. Financing tech-transfer and innovation: An application to the creative industries. In Drones and the Creative Industry Innovative Strategies for European SMEs; Santamarina-Campos, V., Segarra-Oña, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zubielqui, G.C.; O’Connor, A.; Seet, P.S. Intellectual capital system perspective: A case study of government intervention in digital media industries. In Integrating Innovation; Roos, G., O’Connor, A., Eds.; University of Adelaide Press: Adelaide, Australia, 2015; pp. 277–302. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Market orientation and learning organization. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prifti, R.; Alimehmeti, G. Market orientation, innovation, and firm performance—An analysis of Albanian firms. J. Innov. Entrep. 2017, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Pohjola, M.; Koponen, A. Innovation in family firms: An empirical analysis linking organizational and managerial innovation to corporate success. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2012, 6, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M. Corporate strategies for sustainable innovations. In Facilitating Sustainable Innovation through Collaboration; Sarkis, J., Cordeiro, J.J., Brust, D.V., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aagaard, A. Managing sustainable Innovation. In Innovation Management and Corporate Social Responsibility; Altenburger, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar]

- Shanker, R.; Bhanugopan, R.; Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Farrell, M. Organizational climate for innovation and organizational performance: The mediating effect of innovative work behavior. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, E.A.; Quaddus, M. Dimensions of human capital and firm performance: Micro-firm context. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2018, 30, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, N.W.; Dyer, J.H. Human capital and learning as a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 1155–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Jalal, H.; Toulson, P.; Tweed, D. Knowledge sharing success for sustaining organizational competitive advantage. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2013, 7, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Innovation and government intervention: A comparison of Singapore and Hong Kong. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblinger, C.; Surana, K.; Anadon, L.D. Governments as partners: The role of alliances in U.S. cleantech startup innovation. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1458–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanakul, P.; Pinto, J.K. Examining the roles of government policy on innovation. J. High. Technol. Manag. Res. 2014, 25, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, F.J. Survey Research Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publication, Inc.: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, G.D. Determining Sample Size; University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1992; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.S.; Masuku, M.B. Sampling techniques & determination of sample size in applied statistics research: An overview. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2014, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Bosch, F.A.J.V.D.; Volberda, H.W. Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1661–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H. Creating competitive advantage: Linking perspectives of organization learning, innovation behavior and intellectual capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 66, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciolatti, L.; Lee, S.H. Revisiting the relationship between marketing capabilities and firm performance: The moderating role of market orientation, marketing strategy and organizational power. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5597–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, J.G.A. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Evaluating model fit: A synthesis of the structural equation modelling literature. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, London, UK, 19–20 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Silva, E.A.; Wang, Q. The development of creative industries and urban land use: Revisit the interactions from complexity perspective. In Creative Industries and Urban Spatial Structure, Advances in Asian Human-Environmental Research; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ashford, N.A. An innovation-based strategy for a sustainable environment. In Innovation-Oriented Environmental Regulation: Theoretical Approach and Empirical Analysis; Hemmelskamp, J., Rennings, K., Leone, F., Eds.; ZEW Economic Studies: Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 67–107. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A, A.A.; Aimin, W. Market orientation and innovation: A review of literature. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2015, 1, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Racherla, P. Visual representation of knowledge networks: A social network analysis of hospitality research domain. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe, R.A.; Hollenbeck, J.R.; Gerhart, B.; Wright, P.M. Human Resource Management Gaining a Competitive Advantage; Von Hoffmann Press, Inc.: Jefferson City, MO, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, V.H.; Foo, A.T.L.; Leong, L.Y.; Ooi, K.B. Can competitive advantage be achieved through knowledge management? A case study on SMEs. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 65, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexhepi, G.; Ibraimi, S.; Veseli, N. Role of intellectual capital in creating enterprise strategy. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 75, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi-Tavani, S.; Najafi-Tavani, Z.; Naudé, P.; Oghazi, P.; Zeynaloo, E. How collaborative innovation networks affect new product performance: Product innovation capability, process innovation capability, and absorptive capacity. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 73, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Customer orientation | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 2. Competitor orientation | 0.17 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 3. Interfunctional coordination | −0.01 | −0.04 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 4. Business ties | 0.15 ** | 028 ** | 0.05 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 5. Political ties | 0.22 ** | 0.10 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.10 ** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 6. Innovation behaviour | 0.14 ** | 0.10 * | −0.11 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.20 ** | 1.00 | |||||

| 7. Product innovation | 0.14 ** | −.05 | −0.13 ** | −0.12 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.18 ** | 1.00 | ||||

| 8. Government support | −0.03 | 0.10 * | −0.11 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.05 | 0.44 ** | 0.01 | 1.00 | |||

| 9. Firm performance | 0.15 ** | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.12 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.43 ** | 1.00 | ||

| 10. Firm size | 0.08 ** | −0.06 | 0.09 * | 0.09 * | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 1.00 | |

| 11. Firm age | 0.13 ** | 0.10 * | −0.01 | 0.35 ** | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.13 ** | 0.08 * | 0.13 ** | 1.00 |

| Mean | 3.88 | 3.77 | 3.63 | 4.00 | 3.12 | 3.09 | 3.71 | 2.94 | 2.68 | 1.36 | 2.27 |

| Standard deviation | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.48 | 0.86 |

| Variable | Product Innovation | Innovation Behaviour | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Control Variable | ||||||

| Firm Size | 0.04 (0.98) | 0.04 (0.80) | 0.04 (0.89) | −0.09 * (−2.27) | −0.07 (−1.90) | −0.07 (−1.94) |

| Firm Age | −0.02 (−0.43) | −0.04 (−0.88) | −0.02 (−0.36) | 0.16 ** (4.23) | 0.11 ** (3.07) | 0.12 ** (3.55) |

| Moderator Variable | ||||||

| Business Ties (BT) | −0.12 ** (−2.85) | −0.12 ** (−2.90) | −0.12 ** (−2.85) | |||

| Political Ties (PT) | 0.20 ** (5.18) | 0.18 ** (5.06) | 0.11 ** (3.28) | |||

| Independent Variable | ||||||

| Customer Orientation (CUO) | 0.14 ** (3.65) | 0.15 ** (3.85) | ||||

| Competitor Orientation (COO) | −0.05 (−1.30) | 0.01 (0.18) | ||||

| Interfunctional Coordination (IFC) | −0.13 ** (−3.38) | −0.12 ** (−3.18) | ||||

| Government Support (GS) | 0.41 ** (11.75) | 0.40 ** (11.62) | ||||

| Interaction Variable | ||||||

| CUO*BT | 0.14 ** (3.78) | |||||

| COO*BT | −0.15 ** (−3.84) | |||||

| IFC*BT | −0.01 (−0.10) | |||||

| GS*PT | 0.15 ** (4.68) | |||||

| Model Statistics | ||||||

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.23 | 0.26 |

| Variable | Product Innovation | Innovation Behaviour | Firm Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Orientation | 0.13 ** (3.32) | 0.01 (0.20) | |

| Competitor Orientation | −0.01 (−0.08) | −0.02 (−0.69) | |

| Interfunctional Coordination | −0.10 ** (−2.65) | 0.10 ** (3.39) | |

| Government Support | −0.05 (−1.33) | 0.40 ** (11.72) | 0.23 ** (7.54) |

| Innovation Behaviour | 0.19 ** (4.96) | 0.44 ** (13,45) | |

| Product Innovation | 0.17 ** (5.88) | ||

| Firm Size | 0.05 (1.35) | −0.07 * (−1.95) | 0.10 ** (3.26) |

| Firm Age | −0.03 (−0.85) | 0.12 ** (3.60) | 0.01 (0.27) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thongsri, N.; Chang, A.K.-H. Interactions Among Factors Influencing Product Innovation and Innovation Behaviour: Market Orientation, Managerial Ties, and Government Support. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102793

Thongsri N, Chang AK-H. Interactions Among Factors Influencing Product Innovation and Innovation Behaviour: Market Orientation, Managerial Ties, and Government Support. Sustainability. 2019; 11(10):2793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102793

Chicago/Turabian StyleThongsri, Natenapang, and Alex Kung-Hsiung Chang. 2019. "Interactions Among Factors Influencing Product Innovation and Innovation Behaviour: Market Orientation, Managerial Ties, and Government Support" Sustainability 11, no. 10: 2793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102793

APA StyleThongsri, N., & Chang, A. K.-H. (2019). Interactions Among Factors Influencing Product Innovation and Innovation Behaviour: Market Orientation, Managerial Ties, and Government Support. Sustainability, 11(10), 2793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102793