Analysing the Mediating Effect of Heritage Between Locals and Visitors: An Exploratory Study Using Mission Patrimoine as a Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Discuss the limitations of Mission Patrimoine

- Discuss the potential benefits of adopting an ambidextrous management approach for Mission Patrimoine

2. Contextual Framework

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1. Organisational Ambidexterity and Tourism Management

3.2. Heritage/Cultural Tourism Management

3.3. Cultural Tourism Clusters

3.4. Hypothesis

4. Methodology

- A regional director for the Fondation du Patrimoine. This non-profit organization is eligible to receive donations suitable for a tax deduction. This regional director leads an important local network of donors and companies involved in skills-based sponsorship. He has also played an important role in identifying the monuments eligible for the heritage lottery.

- An academic, specialist of cultural tourism in France, who also happens to be knowledgeable about monuments restoration initiatives in France, as well as the challenges of cultural tourism. This academic is also familiar with the various financing mechanisms existing in France for heritage conservation.

- The co-founder of a non-profit association, whose purpose is to restore endangered castles and create sustainable communities around them. He also created a crowdfunding platform dedicated to raising funds for buildings that need to be restored. This platform is used by the NGO, as well as by other restoration project leaders. The founder is an expert in strategies for creating and animating communities around heritage sites (digital strategy, communities around restoration sites).

- The owner of a heritage site. In order to secure funding for the conservation of his domain, he became at creating events aimed at attracting national and foreign visitors, all over the year.

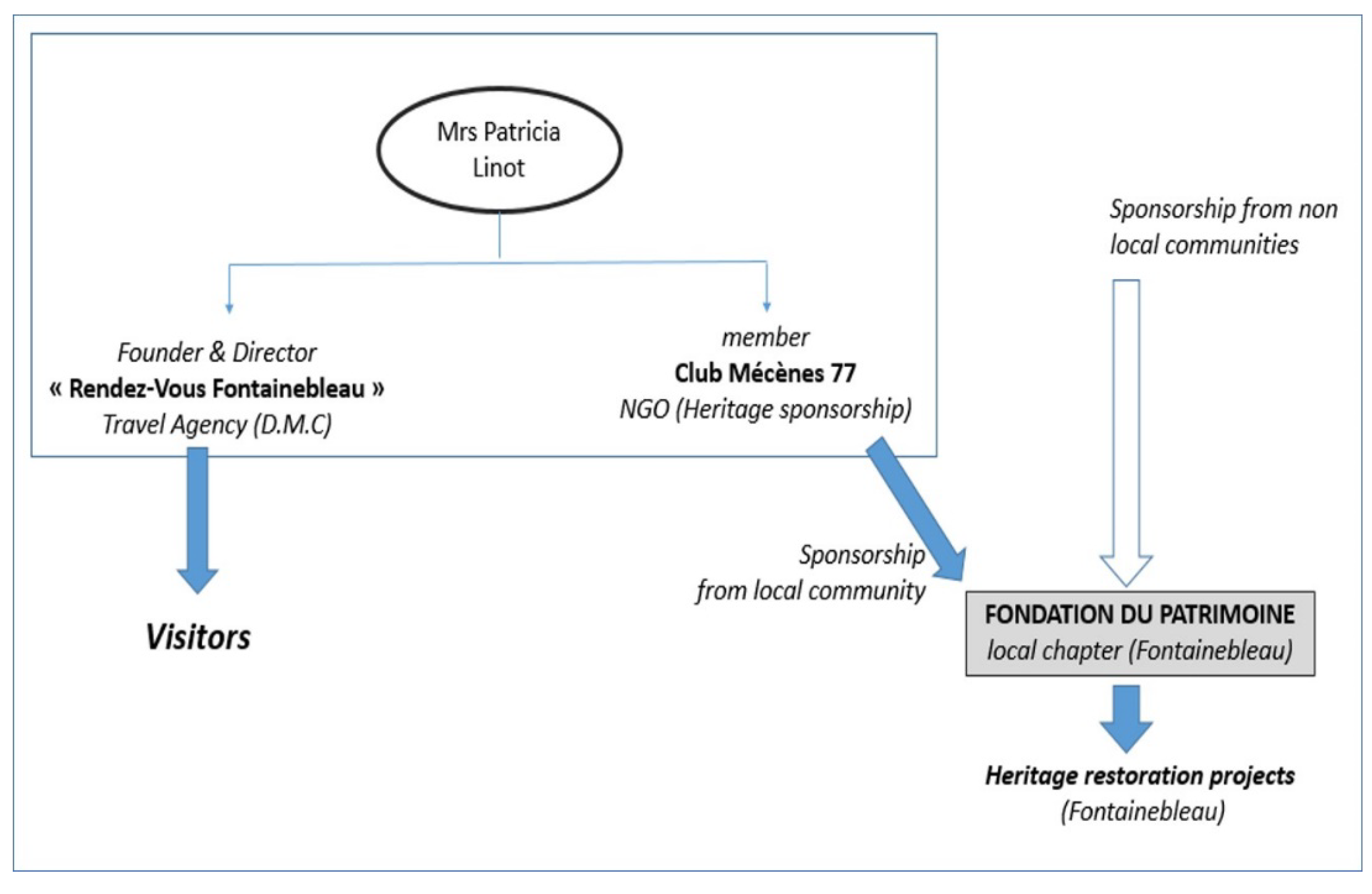

- The founder of a destination management company (DMC). Specialist of a tourist destination including 2 castles of major touristic and heritage importance, she also leads a local NGO bringing together donors and sponsors in skills.

5. Results

5.1. The Heritage Lottery as a Tool to Raise Funds for the Restoration of Pre-Identified Sites

5.2. On the Relevance of the List of Sites to Receive the Proceeds from the Heritage Lottery

5.3. On its Ability to Nurture the Public’s Interest in National Heritage

5.4. On the Heritage Lotto’s Ability to Contribute to National Heritage Besides the Restoration and Conservation Missions

6. Recommendations and Discussions

6.1. Building a Community Around the Heritage Site

6.2. Community Based Heritage as a Tool to Reduce Tourismphobia, Anti-Tourism Movements

7. Conclusions

7.1. Key Findings

7.2. Theoretical Implications

7.3. Practical Implications

- Involvement of all stakeholders. Experts disagree on how monuments are selected in order to be restored. They are arguing the lack of transparency in the process. Additionally, not all stakeholders were involved in the selection process. Among these, there are expert in local heritage; or local residents living close to the selected monuments for restoration. Section 7.1 and Figure 4 are clearly highlighting the importance of having all stakeholders working hand in hand. An ambidextrous management approach could help with the development of a dialogical space. Local community involvement offers stronger ties with a common identity, history and heritage. Furthermore, social inclusion, cohesion and understanding can be strengthened by promoting a sense of shared responsibility towards the places where people live.

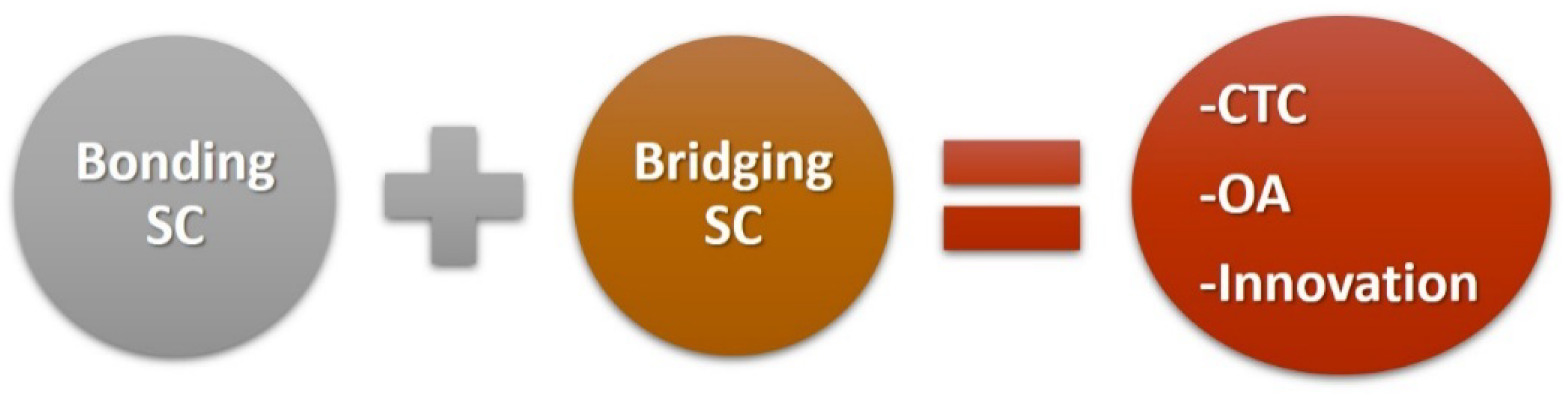

- Sense of belonging. From the interviews that we carried out, it appears that locals are mainly interested with the financial aspect of the project (winning the lottery), more than the social and cultural aspect. Indeed, in Section 3.3. we highlighted the importance of having a sense of belonging and, as highlighted in Section 7.2, community participation helps communities to build a sense of identity. A communication strategy (as part of an overall ambidextrous management approach) would have helped. Indeed, the organisation Adopte un Château in charge of Vaux Le Vicomte castle is a good example of organisation that has managed to gather locals around a project. Indeed, every member of a local community has the opportunity to invest in a local heritage site and subsequently to be an owner of this attraction. This strategy has contributed to develop a strong connection between the heritage site and the locals. Moreover, Vaux Le Vicomte castle, supports the models developed in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 4.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costes, J.-M.; Massin, S.; Etiemble, J. Première Évaluation de l’Impact Socio-Économique des Jeux d’Argent et de Hasard en France; Observatoire des jeux, Ministère de l’économie et des Finances: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Seraphin, H.; Sheeran, P.; Pilato, M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Gowreesunkar, V.; Zaman, M.; Bourliataux-Lajoinie, S. Community based festivals as a tool to tackle tourismphobia and antitourism movements. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séraphin, H.; Zaman, M.; Olver, S.; Bourliataux-Lajoinie, S.; Dosquet, F. Destination branding and overtourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombault, A. Tourisme et création : Les hypermodernes. Mondes Tour. 2011, 4, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haifeng, Y.; Jing, L.; Mu, Z. Rural community participation in scenic spot. A case study of Danxia Mountain of Guangdong, China. J. Hosp. Tour. 2012, 10, 76–112. [Google Scholar]

- Järvinen-Tassopoulos, J. Les jeux d’argent : Un nouvel enjeu social? Pensée Plurielle 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. UNWTO Annual Report 2017; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Seraphin, H. Terrorism and tourism in France: The limitations of dark tourism. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, C.; Babin, B.J.; Carr, J.; Griffin, M.; Zikmund, W.G. Business Research Methods, 1st ed.; Cengage Learning EMEA: Hampshire, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, M.; Wellington, J.J. Research Methods: The Key Concepts; Routledge Key Guides; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, L.; Stevens, R.; Wrenn, B.; Loudon, D. The Essentials of Marketing Research, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon/Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la Culture. Création d’un Loto du Patrimoine. Available online: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/Presse/Archives-Presse/Archives-Communiques-de-presse-2012-2018/Annee-2017/Creation-d-un-loto-du-patrimoine (accessed on 23 April 2019).

- Française des Jeux Mission Patrimoine. Available online: https://www.groupefdj.com/actualite/une-offre-de-jeux-pour-sauver-le-patrimoine-francais.html (accessed on 26 April 2019).

- Ministère de la Culture. List of Sites and Number of Visitors. Available online: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/content/download/170070/1890806/version/2/file/20170917_MC_CP-bilan-JEP-2017.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2019).

- Mihalache, M.; Mihalache, O.R. Organizational ambidexterity and sustained performance in the tourism industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 56, 142–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinthal, D.A.; March, J.G. The myopia of learning. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Exploratory Innovation, Exploitative Innovation, and Performance: Effects of Organizational Antecedents and Environmental Moderators. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1661–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séraphin, H.; Butcher, J. Tourism Management in the Caribbean. Caribb. Q. 2018, 64, 254–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pérez, Á.; García-Villaverde, P.M.; Elche, D. The mediating effect of ambidextrous knowledge strategy between social capital and innovation of cultural tourism clusters firms. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1484–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Yallop, A.C.; Capatîna, A.; Gowreesunkar, V.G. Heritage in tourism organisations’ branding strategy: The case of a post-colonial, post-conflict and post-disaster destination. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 12, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fazio, S.; Modica, G. Historic Rural Landscapes: Sustainable Planning Strategies and Action Criteria. The Italian Experience in the Global and European Context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séraphin, H.; Smith, S.M.; Scott, P.; Stokes, P. Destination management through organisational ambidexterity: Conceptualising Haitian enclaves. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunt, P.; Horner, S.; Semley, N. Research Methods in Tourism, Hospitality and Events Management, 1st ed.; SAGE Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- La Croix Succès pour le Tirage du Loto du Patrimoine. Available online: http://bit.ly/LaCrxLotoPatrimoine (accessed on 23 April 2019).

- World Heritage and Sustainable Development. New Directions in World Heritage Management; Larsen, P.B., Logan, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Hunter, C. Community involvement for sustainable heritage tourism: A conceptual model. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 5, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazaizeh, M.M.; Hallo, J.C.; Backman, S.J.; Norman, W.C.; Vogel, M.A. Value orientations and heritage tourism management at Petra Archaeological Park, Jordan. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, C.; Ladkin, A.; Fletcher, J. Stakeholder collaboration and heritage management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisrisak, T. Conservation of Bangkok old town. Habitat Int. 2009, 33, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W. Problem issues of public participation in built-heritage conservation: Two controversial cases in Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignataro, G.; Rizzo, I. The Political Economy of Rehabilitation: The case of the Benedettini Monastery. In Economic Perspectives on Cultural Heritage; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 1997; pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, E. Conservation and Planning; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Clarck, K. From Regulation to Participation: Cultural heritage, sustainable development and citizenship. In Forward Planning: The Function of Cultural Heritage in a Changing Europe; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2000; pp. 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage, Conservation and Communities; Chitty, G., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon/Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Modica, G.; Zoccali, P.; Di Fazio, S. The e-Participation in Tranquillity Areas Identification as a Key Factor for Sustainable Landscape Planning. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2013; Murgante, B., Misra, S., Carlini, M., Torre, C.M., Nguyen, H.-Q., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Gervasi, O., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 7973, pp. 550–565. [Google Scholar]

- Power, A.; Smyth, K. Heritage, health and place: The legacies of local community-based heritage conservation on social wellbeing. Health Place 2016, 39, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, B. Deprogramming planning: Collaboration and inclusion in new urban development. Urban Policy Res. 2004, 22, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.G. Alternative tourism: Concepts, classifications, and questions. In Tourism Alternatives: Potentials and Problems in the Development of Tourism; Eadington, W.R., Smith, V.L., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wearing, S.; McDonald, M. The Development of Community-based Tourism: Re-thinking the Relationship Between Tour Operators and Development Agents as Intermediaries in Rural and Isolated Area Communities. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.B. Community-based cultural tourism: Issues, threats and opportunities. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P.; Gössling, S.; Klijs, J.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Dijkmans, C.; Eijgelaar, E.; Hartman, S.; Heslinga, J.; Isaac, R.; et al. Research for TRAN Committee—Overtourism: Impact and Possible Policy Responses; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Séraphin, H.; Platania, M.; Spencer, P.; Modica, G. Events and Tourism Development within a Local Community: The Case of Winchester (UK). Sustainability 2018, 10, 3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.V. Is over-tourism the downside of mass tourism? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 415–416. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G.; Konovalov, E.; Murphy, L.; McGehee, N.G.; Schurmann, A. Linking tourism to social capital in destination communities. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadi, S. Impacts of culture and heritage-led development programmes. In Urban Heritage, Development and Sustainability. International Frameworks, National and Local Governance; Labadi, S., Logan, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 137–150. [Google Scholar]

- Huong, P.T.T. Living heritage, community participation and sustainability. Redefining development strategies in the Hoi An Ancient Town World Heritage property, Vietnam. In Urban Heritage, Development and Sustainability. International Frameworks, National and Local Governance; Labadi, S., Logan, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 274–290. [Google Scholar]

- Trejos, B.; Chiang, L.-H.N. Local economic linkages to community-based tourism in rural Costa Rica. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2009, 30, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, S.; Kunc, M.; Jones, E.; Tiffin, S. Supporting innovation for tourism development through multi-stakeholder approaches: Experiences from Africa. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; Melo, A.I. The Triple Helix Model as Inspiration for Local Development Policies: An Experience-Based Perspective. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 1675–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.; Zawdie, G. Triple helix in developing countries—Issues and challenges. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2008, 20, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Area | Author | Year | Journal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Destination Management | Mihalache & Mihalache | 2016 | Annals of Tourism Research |

| Martinez-Perez et al. | 2016 | Int. Journal of Cont. Hosp. Mgt | |

| Seraphin et al. | 2018a | Journal of Dest. Marketing & Mgt. | |

| Seraphin et al. | 2018b | Journal of Dest. Marketing & Mgt. | |

| Hospitality | Tang | 2014 | Inter. Journal of Hosp. Mgt. |

| Tsai | 2015 | Current Issues In Tourism | |

| Ubeda-Garcia et al. | 2016 | Cornell Hospitality Quarterly | |

| Cheng et al. | 2016 | Inter. Journal of Hosp. Mgt. | |

| Bouzari & Karatepe | 2017 | Int. Journal of Cont. Hosp. Mgt. | |

| Wang et al. | 2018 | Int. Journal of Cont. Hosp. Mgt. | |

| Ubeda-Garcia et al. | 2018 | Int. Journal of Cont. Hosp. Mgt. | |

| Ma et al. | 2018 | Inter. Journal of Hosp. Mgt. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beal, L.; Séraphin, H.; Modica, G.; Pilato, M.; Platania, M. Analysing the Mediating Effect of Heritage Between Locals and Visitors: An Exploratory Study Using Mission Patrimoine as a Case Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113015

Beal L, Séraphin H, Modica G, Pilato M, Platania M. Analysing the Mediating Effect of Heritage Between Locals and Visitors: An Exploratory Study Using Mission Patrimoine as a Case Study. Sustainability. 2019; 11(11):3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113015

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeal, Luc, Hugues Séraphin, Giuseppe Modica, Manuela Pilato, and Marco Platania. 2019. "Analysing the Mediating Effect of Heritage Between Locals and Visitors: An Exploratory Study Using Mission Patrimoine as a Case Study" Sustainability 11, no. 11: 3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113015

APA StyleBeal, L., Séraphin, H., Modica, G., Pilato, M., & Platania, M. (2019). Analysing the Mediating Effect of Heritage Between Locals and Visitors: An Exploratory Study Using Mission Patrimoine as a Case Study. Sustainability, 11(11), 3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113015