Introducing the Concept of Organic Products to the Primary School Curriculum

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identity of the Sample

3.2. Intervention Effect

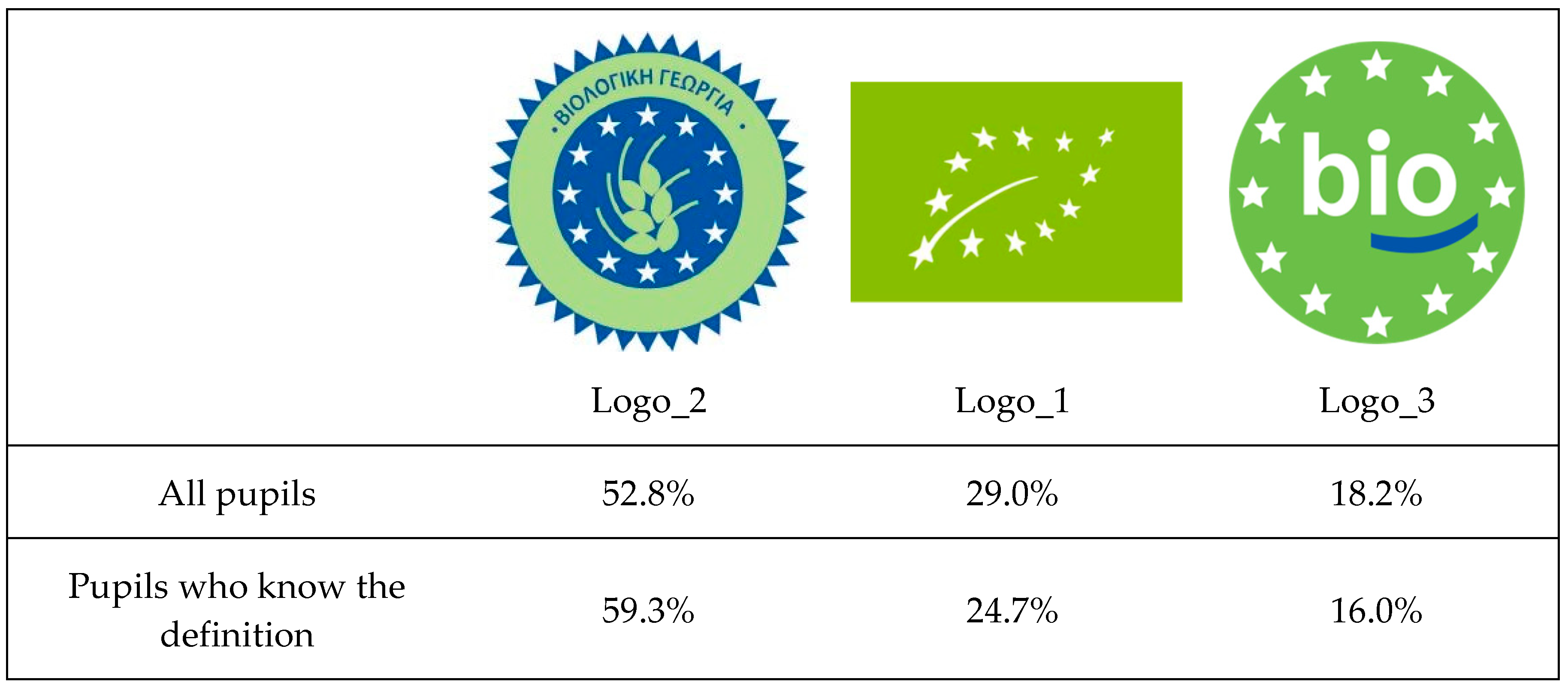

3.3. Preferred Logo and Design Characteristics

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- European Commission. Special Eurobarometer 389 Europeans Attitudes towards Food Security, Food Quality and the Countryside. Available online: http://ec.europa.e (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Brantsæter, A.L.; Ydersbond, T.A.; Hoppin, J.A.; Haugen, M.; Meltzer, H.M. Organic Food in the Diet Exposure and Health Implications. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2017, 38, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council Regulation (EC). No 834/2007 of 28 June 2007 on Organic Production and Labelling of Organic Products and Repealing Regulation (EEC) No 2092/91; IFOAM EU GROYP: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Colom-Gorgues, A. The Challenges of Organic Production and Marketing in Europe and Spain: Innovative Marketing for the Future with Quality and Safe Food Products. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2009, 21, 166–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. The EU’s Organic Food Market: Facts and Rules (Infographic). 2016. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20180404STO00909/the-eu-s-organic-food-market-facts-and-rules-infographic (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Quah, S.; Tan, A. Consumer Purchase Decisions of Organic Food Products: An Ethnic Analysis. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2009, 22, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, F.A.; Rennie, D. Consumer Perceptions towards Organic. Food Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 49, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybowska-Brzezińska, M.; Grzywińska-Rąpca, M.; Żuchowski, I.; Bórawski, P. Organic Food Attributes Determing Consumer Choices. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2017, 2, 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- McReynolds, K.; Gillan, W.; Naquin, M. An Examination of College Students’ Knowledge, Perceptions, and Behaviors Regarding Organic Foods. Am. J. Health Educ. 2018, 49, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, C.; Janssen, M.; Smith, L.; Hamm, U.; Padel, S. UK consumer reactions to organic certification logos. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Consumer preferences and willingness-to-pay for organic certification logos: Recommendations for actors in the organic sector. In Agricultural and Food Market Faculty of Organic Agricultural Sciences; University of Kassel: Kassel, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar, H.; Tegegne, F.; Baryeh, K.; Illukpitiya, P. Attitudes and Willingness to Pay More for Organic Foods by Tennessee Consumers. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Chang, H.S.; Leviten-Reid, C. Organic food demand: A focus group study involving Caucasian and African-American shoppers. Agric. Hum. Values 2006, 23, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Product labeling in the market for organic food. Consumer preferences and willingness-to-pay for different organic certification logos. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 25, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, K.; Padel, S.; Zanoli, R. EU organic logo and its perception by consumers. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1506–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fotopoulos, C.; Krystallis, A. Purchasing motives and profile of the Greek organic consumer: A countryside survey. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 730–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oystein, S.; Persillet, V.; Sylvander, B. The Consumers Faithfulness and Competence in Regard to Organic Products: Comparison between France and Norway. In Proceedings of the 14th IFOAM Organic World Congress 2002, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–24 August 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiou, C.N.; Keramitsoglou, K.M.; Kalogeras, N.; Tsagkaraki, M.I.; Kalatzi, I.; Tsagarakis, K.P. Can the “Euro-Leaf” Logo Affect Consumers’ Willingness-To-Buy and Willingness-To-Pay for Organic Food and Attract Consumers’ Preferences? An Empirical Study in Greece. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Nayga, R.M.; Capps, O. The Effect of New Food Labeling on Nutrient Intakes: An Endogenous Switching Regression Analysis; AAEA: Nashville, TN, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakas, K. Information asymmetries and consumption decisions in organic food product markets. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2002, 50, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotschi, E.; Vogel, S.; Lindenthal TLarcher, M. The Role of Knowledge, Social Norms, and Attitudes Toward Organic Products and Shopping Behavior: Survey Results from High School Students in Vienna. J. Environ. Educ. 2009, 41, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M. Determinants of organic food purchases: Evidence from household panel data. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandercammen, M. Aankopen: Kinderen Beslissen; zo Gebruiken de Merken de Generationele Marketing [Purchaces: Children Decide; That Is How Brands Use Generational Marketing]; OIVO (Onderzoeks—En Informatiecentrum van de Verbruikersorganisaties): Brussel, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zografakis, N.; Menegaki, A.N.; Tsagarakis, K.P. Effective education for energy efficiency. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 3216–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramitsoglou, K.M.; Tsagarakis, K.P. Raising effective awareness for domestic water saving: Evidence from an environmental educational programme in Greece. Water Policy 2011, 13, 828–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaut, A.M.K. Consumer Response to Innovative Products: With Application to Foods; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Riefer, A.; Hamm, U. Organic food consumption in families with juvenile children. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerardo, H.; Nunez, H.G.; Kovaleski, A.P.; Darnell, R.L. Formal Education Can Affect Students’ Perception of Organic Produce. Hort Technol. 2014, 24, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Dahm, M.J.; Samonte, A.V.; Shows, A.R. Organic foods: Do Eco-Friendly Attitudes predict Eco-Friendly behaviors? J. Am. Colleague Health 2009, 58, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liefländer, A.; Fröhlich, G.; Bogner, F.; Schultz, P. Promoting connectedness with nature through environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobbelaar, D.J.; Casimir, G.; Borghuis, J.; Marks, I.; Meijer, L.; Zebeda, S. Adolescents’ attitudes towards organic food: A survey of 15- to 16-year old school children. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystallis, A.; Fotopoulos, C.; Zotos, Y. Organic Consumers’ Profile and Their Willingness to Pay (WTP) for Selected Organic Food Products in Greece. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2006, 19, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijne, W.; Stienstra, S.; Buizert, N.; Borst, J. Biologisch Eigenlijk heel Logisch, of toch niet...? Hoe Denken Jongeren Erover? [Organic Actually Quite Logical, or Not…? How Do Young People Think about It?]; Werkstuk, Gymnasium Apeldoorn: Apeldoorn, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, T. ‘Nature’ and the ‘environment’ in Jamaica’s primary school curriculum guides. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickinson, M. Learners and learning in environmental education: A critical review of the evidence. Environ. Educ. Res. 2001, 7, 207–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, E.W.; Pell, R.G. Me and the environmental challenges: A survey of English secondary school students’ attitudes towards the environment. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2006, 28, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flogaitis, E.; Agelidou, E. Kindergarten teachers’ conceptions about nature and the environment. Environ. Educ. Res. 2003, 9, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, G.P. Moral spaces, the struggle for an intergenerational environmental ethics and the social ecology of families: An ‘other’ form of environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinis, A.; Kabassi, K.; Dimitriadou, C.; Karris, G. Pupils’ environmental awareness of natural protected areas: The case of Zakynthos Island. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2018, 7, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, F.; Taylor, N. Climate of concern: A search for effective strategies for teaching children about Global Warming. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2009, 4, 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Badjanova, J.; Dzintra, I.; Elga, D. Holistic Approach in Reorienting Teacher Education towards the Aim of Sustainable Education: The Case Study from the Regional University in Latvia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 2931–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Official Journal of the Greek Government, 304B/13-03-03. Available online: http://www.pi-schools.gr/download/programs/depps/fek304.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2019). (In Greek).

- Rawcliffe, F. Practical Problem Projects; R. Compton & Co.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs, S. Intellectual Growth in Young Children; G. Routledge & Sons, Ltd.: London, UK, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Food Organic Products I. Video from National TV Chanel 3 (In Greek). Available online: www.youtube.com/watch?v=1nmKjcH1Pug (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- EU 2010. Commission Regulation (EU) No 271/2010 of 24 March 2010 amending Regulation (EC) No 889/2008 Laying down Detailed Rules for the Implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007, as Regards the Organic Production logo of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32010R0271 (accessed on 13 August 2018).

- ECC 1991. Council Regulation (EEC) No 2092/91 of 24 June 1991 on Organic Production of Agricultural Products and Indications Referring Thereto on Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs. Available online: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/79cf3c57-e66f-4932-a653-c45dc68e3665/language-en (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Bio-markt.info. The New EU Logo. 2008. Available online: http://bio-markt.info/kurzmeldungen/Das_neue_EU_Logo.html (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- biomanantial. The European Commission Cut the New European Bio Logo. 2008. Available online: https://en.biomanantial.com/the-european-commission-cut-the-new-european-bio-logo-a-1045-en.html (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Matsagouras, H. The Interdependence in School Knowledge: Conceptual Restoration and Work Plans; Gregory: Athens, Greece, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, W.H. The Project Method: The Use of the Purposeful Act in the Education Process. Teach. Coll. Rec. 1918, 19, 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Knoll, M. Project Method. In Encyclopedia of Educational Theory and Philosophy; Phillips, D.C., Ed.; Stanford University Sage: Stanford, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 665–669. [Google Scholar]

- Caduto, M.J. A Guide on Environmental Values Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Barraza, L. Children’s Drawings about the Environment. Environ. Educ. 1999, 5, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.H. Framing Education as Art: The Octopus Has a Good Day; Teachers’ College: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, E. The Communicative Potential of Young Children’s Drawings. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G. Before Writing: Rethinking the Paths to Literacy; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, D.; Brechet, C.; Baldy, R. Expressive Strategies in Drawing are Related to Age and Topic. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2007, 31, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligorio, M.B.; HSchwartz, H.N.; D’Aprile, G.; Philhour, D. Children’s representations of learning through drawings. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2017, 12, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farokhi, M.; Hashemi, M. The Analysis of Children’s Drawings: Social, Emotional, Physical, and Psychological aspects. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 2219–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiss, R.; Hiltmann, H. Der farbpyramiden-Test nach Pfister; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Bellas, T. The Child’s Sketch as a Means and Object of Research in the Hands of the Teacher; Greek Letters: Athens, Greek, 2000; pp. 132–133. [Google Scholar]

- Furth, G. The Secret World of Drawings; Sigo Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Serin, Y. Figure, color, size and content relations in children’s picture. Univ. Fac. Educ. J. 2003, 4, 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Alschuler, R.; Hattwich, L.A. Painting and Personality: A Study of Young Children; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg, R. Analyzing Children’s Art; Mayfield: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kosta, A.D.; Tsagarakis, K.P. Introducing the Concept of Organic Products to the Primary School Curriculum. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3559. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133559

Kosta AD, Tsagarakis KP. Introducing the Concept of Organic Products to the Primary School Curriculum. Sustainability. 2019; 11(13):3559. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133559

Chicago/Turabian StyleKosta, Aikaterini D., and Konstantinos P. Tsagarakis. 2019. "Introducing the Concept of Organic Products to the Primary School Curriculum" Sustainability 11, no. 13: 3559. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133559