Sustainability Assessment of Agricultural Systems in Paraguay: A Comparative Study Using FAO’s SAFA Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture Systems (SAFA)

2.2. Selection of Agricultural Systems, Area, and Case Studies

2.3. Data Collection

- -

- Semi-structured interviews: conducted in the selected farms, lasting between 35–100 min aimed at answering a series of questions based on the SAFA indicators [52]. The principal investigator interviewed each representative of the case studies that were taken into consideration, except for the three cases of indigenous agriculture, where a single interview was addressed to a key informant. The questions have been translated from English into Spanish, and the interviews have been transcribed in the original language.

- -

- Direct observation: of farms taking into account the indicators to be analyzed. Visits and direct observations were made in all the farms involved in the study, with the exception of the 3A, 1B, and indigenous communities due to the impossibility of visiting the area without a Guaraní speaking guide and being accepted by the communities.

- -

- Documents and literature review in order to integrate the data and concepts that give scientific support to the work. Paraguayan laws and regulations, official documents such as agricultural censuses, specialized literature, technical documents of organizations working in the national and international sector, and academic and scientific texts were taken into consideration.

3. Results and Discussion

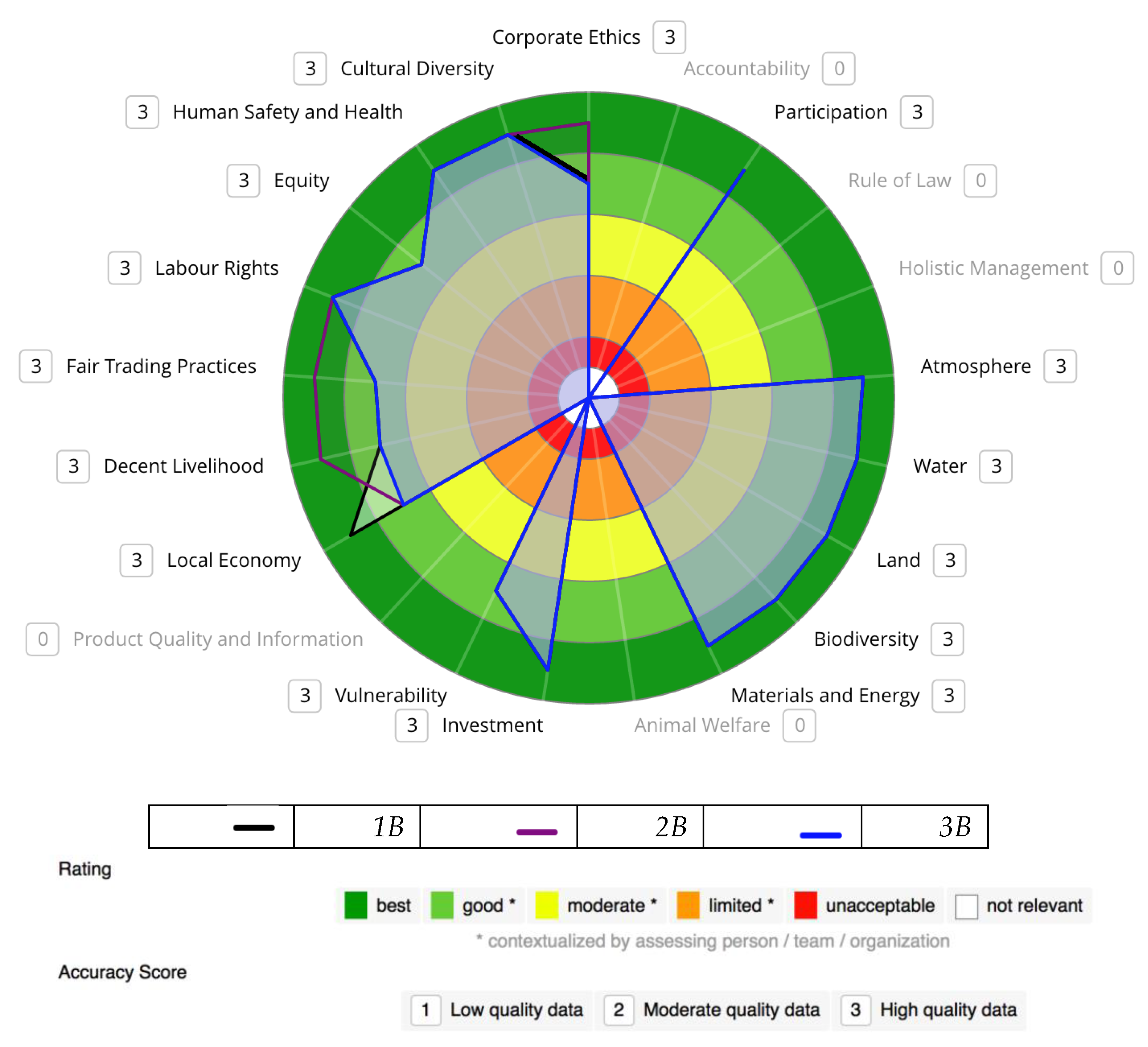

3.1. Evaluation of the Sustainability Level of Agricultural Systems in a Comparative Way for Each Agricultural System

3.1.1. Agribusiness

3.1.2. Agroecological Peasant Family Farming

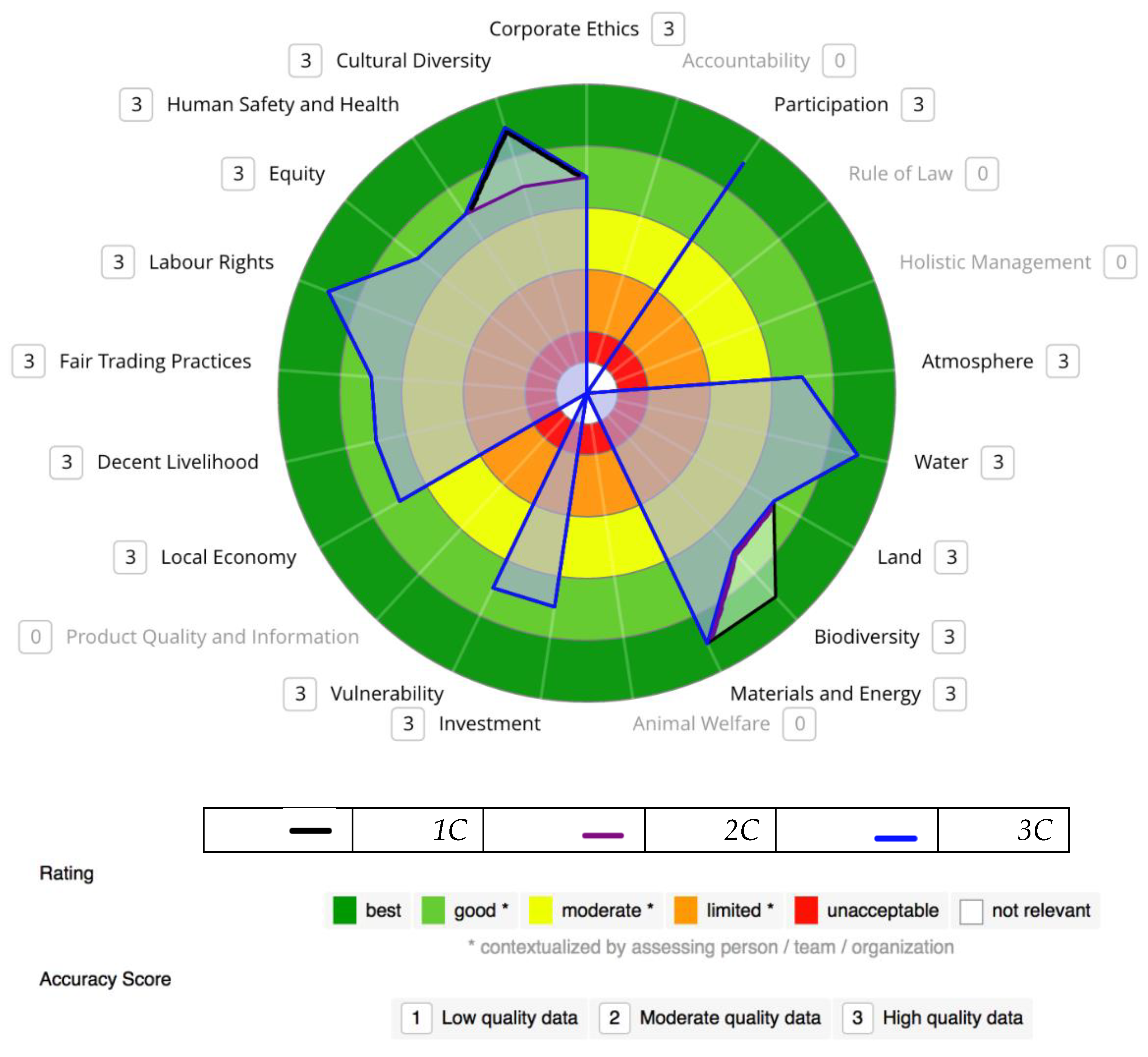

3.1.3. Conventional Peasant Family Farming

3.1.4. Neo-Rural Farming

3.1.5. Indigenous Agriculture

3.2. Evaluation of the Sustainability Level of Agricultural Systems in a Comparative Way for Each Dimension

3.2.1. Good Governance

3.2.2. Environmental Integrity

3.2.3. Economic Resilience

3.2.4. Social Well-Being

3.3. General Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Perspectivas del Medio Ambiente Mundial 2002: GEO-3: Pasado, Presente y Futuro; Ediciones Mundi-Prensa: Madrid, Spain, 2002; p. 425. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/4538pressowg13.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Merico, L.F.K. Proposta metodológica de avaliação do desenvolvimento econômico na região do Vale do Itajaí (SC) através de indicadores ambientais. Rev. Dyn. 1997, 5, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Baroni, M. Ambigüidades e deficiências do conceito de desenvolvimento sustentável. Rev. Adm. Empres. 1992, 32, 14–24. Available online: htp://www.scielo.br/pdf/rae/v32n2/a03v32n2.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2019). [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). El Future de la Alimentación y la Agricultura. Tendencias y Desafíos. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6881s.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Loaiza Cerón, W.; Reyes Trujillo, A.; Carvajal Escobar, Y. Aplicación del Índice de Sostenibilidad del Recurso Hídrico en la Agricultura (ISRHA) para definir estrategias tecnológicas sostenibles en la microcuenca Centella. Ing. Desarro. 2012, 30, 160–181. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/inde/v30n2/v30n2a03.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Altieri, M.; Nicholls, C. Un método agroecológico rápido para la evaluación de la sostenibilidad de cafetales. Manejo Integr. Plagas Agroecol. 2002, 64, 17–24. Available online: http://repositorio.bibliotecaorton.catie.ac.cr/bitstream/handle/11554/6866/A2039e.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Sarandón, S.J. El desarrollo y uso de indicadores para evaluar la sustentabilidad de los agroecosistemas. In Agroecología: El Camino Hacia una Agricultura Sustentable; Ediciones Científicas Americanas: La Plata, Argentina, 2002; pp. 393–414. Available online: https://wp.ufpel.edu.br/consagro/files/2010/10/SARANDON-cap-20-Sustentabilidad.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Zaldivar, P. Concepciones teórico-metodológicas para el análisis del medio ambiente y la agricultura. In Ciencias Ambientales y Agricultura; Tornero, C.M., López, O.J., Aragón, G.A., Eds.; Publicación especial de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla: Puebla, México, 2006; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Green, G.P. Sustainability and rural communities. Kans. J. Law Public Policy 2014, 23, 421–436. Available online: http://law.ku.edu/sites/law.drupal.ku.edu/files/docs/law_journal/v23/10%20Green_Formatted_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Vara Sánchez, I.; Cuéllar Padilla, M. Biodiversidad cultivada: Una cuestión de coevolución y transdisciplinariedad. Ecosistemas 2013, 22, 1–5. Available online: https://www.revistaecosistemas.net/index.php/ecosistemas/article/view/758 (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Altieri, M.A.; Koohafkan, P. Enduring Farms: Climate Change, Smallholders and Traditional Farming Communities; Third World Network: Penang, Malaysia, 2008; pp. 1–63. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docs/eims/upload/288618/Enduring_Farms.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Brokensha, D.W.; Warren, D.M.; Werner, O. Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Development; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1980; p. 473. [Google Scholar]

- Marzall, K. Agrobiodiversidade e resiliência de agroecossistemas: Bases para segurança ambiental. Rev. Bras. Agroecol. 2007, 2, 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Castillo, R. Agroecologías: Atributos de sustentabilidad. InterSedes 2002, 3, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.A.; Toledo, V.M. The Agroecological revolution in Latin America: Rescuing nature, ensuring food sovereignty and empowering peasants. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 587–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla Guzmán, E. De la Sociología Rural a la Agroecología; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2006; p. 251. [Google Scholar]

- Sarandón, S.J. The development and use of sustainability indicators: A need for organic agriculture evaluation. In Proceedings of the XII International Scientific Conference (IFOAM), Mar del Plata, Argentina, 15–19 November 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Frausto, O.; Rojas, J.; Santos, X. Indicadores de desarrollo sostenible a nivel regional y local: Análisis de Galicia, España, y Cozumel, México. In Estudios Multidisciplinarios en Turismo; Guevara Ramos, R., Ed.; SECTUR: Ciudad de México, México, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 175–197. Available online: https://cedocvirtual.sectur.gob.mx/janium/Documentos/9357.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2019).

- Loaiza Cerón, W.; Carvajal Escobar, Y.; Ávila Díaz, A.J. Evaluación agroecológica de los sistemas productivos agrícolas en la microcuenca Centella (Dagua, Colombia). Colomb. For. 2014, 17, 161–179. Available online: https://revistas.udistrital.edu.co/ojs/index.php/colfor/article/view/5173/9647 (accessed on 24 April 2019). [CrossRef]

- Gallopín, G.C. Environmental and sustainability indicators and the concept of situational indicators. A system approach. Environ. Model. Assess. 1996, 1, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, L. Operacionalización del Concepto de Sostenibilidad. Un Método Basado en la Productividad Total; Ponencia del Sexto Encuentro de RIMISP: Campinas, Brasil, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Agosto, P.; Palau, M. Hacia la Construcción de la Soberanía Alimentaria. Desafíos y Experiencias de Paraguay y Argentina; Base Investigaciones Sociale, Equipo de Educación Popular Pañuelos en Rebeldía; CIFMSL: Asunción, Paraguay, 2015; p. 110. [Google Scholar]

- Palau Viladesau, T. El movimiento campesino en el Paraguay: Conflictos, planteamientos y desafíos. In Observatorio Social de América Latina (OSAL); CLACSO: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005; Volume 16, pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, G. Mapeamiento del Extractivismo; Base Investigaciones Sociales: Asunción, Paraguay, 2016; pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Guereña, A.; Rojas Villagra, L.; Jára, Y.V.Y. Los Dueños de la Tierra en Paraguay; OXFAM: Asunción, Paraguay, 2016; p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- CEPALSTAT—Bases de Datos y Publicaciones Estadísticas. Available online: http://estadisticas.cepal.org/cepalstat/Perfil_Nacional_Social.html?pais=PRY&idioma=spanish (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Ortega, G. Agronegocios vs agricultura campesina: Resistir y producir. In Con la Soja al Cuello 2016. Informe sobre Agronegocios en Paraguay; Palau, M., Ed.; Base Investigaciones Sociales: Asunción, Paraguay, 2016; pp. 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Doughmann, R. La Chipa y la Soja. La Pugna Gastro-Política en la Frontera Agroexpotadora del Este Paraguayo; Base Investigaciones Sociales: Asunción, Paraguay, 2011; p. 370. Available online: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Paraguay/base-is/20170331031439/pdf_73.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Ortega, G. El dilema de la agricultura campesina durante el gobierno Cartes. In Con la Soja al Cuello 2018. Informe sobre Agronegocios en Paraguay; Palau, M., Ed.; Base Investigaciones Sociales: Asunción, Paraguay, 2018; pp. 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Finnis, E.; Benítez, C.; Candia Romero, E.F.; Aparicio Meza, M.J. Changes to agricultural decision making and food procurement strategies in rural Paraguay. Lat. Am. Res. Rev. 2012, 47, 180–190. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236811318_Changes_to_Agricultural_Decision_Making_and_Food_Procurement_Strategies_in_Rural_Paraguay (accessed on 28 April 2019). [CrossRef]

- Insfrán Ortiz, A.; Rey Benayas, J.M. La cultura de la restauración de los ecosistemas: Una tarea pendiente en sistemas agrícolas tropicales y en el BAAPA en Paraguay. In Ecología Humana Contemporanea: Apuntes y visiones en la complejidad del desarrollo, 1st ed.; Insfrán Ortiz, A., Aparicio Meza, M.J., Gomes Alvim, R., Eds.; Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias, Universidad Nacional de Asunción: San Lorenzo, Paraguay, 2017; pp. 17–41. Available online: http://sabeh.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ECOLOGIA-HUMANA-CONTEMPORANEA-internet-red.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2019).

- Altieri, M.; Nicholls, C.I. Agroecología. Teoría y Práctica Para una Agricultura Sustentable, 1st ed.; Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente: Mexico City, Mexico, 2000; p. 250. Available online: htp://www.agro.unc.edu.ar/~biblio/AGROECOLOGIA2%5B1%5D.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2019).

- FIDA; MERCOSUR; IICA; FAO. Caracterización de la Agricultura Familiar en Paraguay; IICA: Asunción, Paraguay, 2004; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Barril, A.; Almada, F. La Agricultura Familiar en los Países del Cono Sur; IICA: Asunción, Paraguay, 2007; p. 189. Available online: http://orton.catie.ac.cr/repdoc/A2321e/A2321e.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2019).

- Echenique, J. Caracterización de la Agricultura Familiar; BID-FAO: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gasso, V.; Oudshoorn, F.W.; De Olde, E.; Sørensen, C.A. Generic sustainability assessment themes and the role of context: The case of Danish maize for German biogas. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 49, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Olde, E.M.; Oudshoorn, F.W.; Sørensen, C.A.; Bokkers, E.A.; De Boer, I.J. Assessing sustainability at farm-level: Lessons learned from a comparison of tools in practice. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 66, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Olde, E.M.; Sautier, M.; Whitehead, J. Comprehensiveness or implementation: Challenges in translating farm-level sustainability assessments into action for sustainable development. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 85, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). SAFA Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture Systems: Guidelines Version 3.0; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2014; p. 253. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3957e.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). SAFA Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture Systems: Indicators; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2013; p. 271. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/nr/sustainability_pathways/docs/SAFA_Indicators_final_19122013.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). SAFA Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture Systems: Tool User Manual Version 2.2.40; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2014; p. 20. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4113e.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Altieri, M. Agroecologia. In Bases Científicas de la Agricultura Alternativa; Ediciones CETAL: Valparaíso, Chile, 1983; p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M. Agroecologia. In Bases Científicas Para una Agricultura Sustentable; Editorial Nordan-Comunidad: Montevideo, Uruguay, 1999; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Icei. La Agricultura Familiar: Sus Potencialidades y Desafios. Elementos Para la Reflexión; Biblioteca Icei Mercosur: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2011; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Villagra, L.; Arrom, C.H.; Ruoti, M.; García, S.; García, C.; Samudio, M. Perspectivas de Sostenibilidad de Comunidades Campesinas en el Modelo de Desarrollo Actual; Informe Técnico; Base Investigaciones—Universidad Nacional de Asunción—CONACYT: Asunción, Paraguay, 2017; p. 122. Available online: https://www.portalguarani.com/2248_luis_rojas_villagra/33791_perspectivas_de_sostenibilidad_de_comunidades_campesinas_en_el_modelo_de_desarrollo_actual__luis_rojas_villagra__ano_2017.html (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Mailfert, K. New farmers and networks: How beginning farmers build social connections in France. Tijdschrift Economische Soc. Geogr. 2007, 98, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G.; Malandrin, V.; Rossi, A. Trade-off or convergence? The role of food security in the evolution of food discourse in Italy. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 29, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belasco, W. Food and the counterculture: A story of bread and politics. In The Cultural Politics of Food and Eating; Watson, J., Caldwell, M., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Merlo, V. Voglia di Campagna: Neoruralismo e Città; Città Aperta Edizioni: Troina, Italy, 2006; p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Orria, B.; Luise, V. Innovation in rural development: “neo-rural” farmers branding local quality of food and territory. IJPP Ital. J. Plan. Pract. 2017, 7, 1–29. Available online: https://air.unimi.it/retrieve/handle/2434/598461/1093923/Orria%20B.%2C%20Luise%20V.%2C%20Innovation%20in%20rural%20development%3A%20“neo-%20rural”%20farmers%20branding%20local%20quality%20of%20food%20and%20territorypdf.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Vargas Lehner, F. Evaluación de la Sustentabilidad de Agroecosistemas en Tres Comunidades Mbya Guarani del Departamento de Caaguazù: Una Propuesta Metodológica; Carrera de Ingeniería en Ecologia Humana, Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias, Universidad Nacional de Asunción: Asunción, Paraguay, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, M. Condiciones de vida y estructuras domésticas campesinas del grupo doméstico guaraní a la familia nuclear paraguaya. In Pasado y Presente de la Realidad Paraguaya; La Cuestión Agraria, CEPS: Asunción, Paraguay, 2001; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). La Estrategia de la FAO Sobre el Cambio Climático; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2007; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7175s.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Vicente, C.A. La agricultura campesina enfría el planeta. In Con la Soja al Cuello 2016. Informe sobre Agronegocios en Paraguay; Palau, M., Ed.; Base Investigaciones Sociales: Asunción, Paraguay, 2016; pp. 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Apipé, G. Paraguay importa el 6,2% de agroquímicos vendidos en el mundo. In Con la Soja al Cuello 2018. Informe sobre Agronegocios en Paraguay; Palau, M., Ed.; Base Investigaciones Sociales: Asunción, Paraguay, 2018; pp. 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Apipé, G. A medida que aumenta el uso de transgénicos, más veneno se verte sobre los campos de cultivo. In Con la Soja al Cuello 2017. Informe sobre Agronegocios en Paraguay; Palau, M., Ed.; Base Investigaciones Sociales: Asunción, Paraguay, 2017; pp. 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Graeub, B.E.; Chappell, M.J.; Wittman, H.; Ledermann, S.; Kerr, R.B.; Gemmill-Herren, B. The state of family farms in the world. World Dev. 2016, 87, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalì, P.; Velazquéz, M. Paraguay. Panorama de la Protección Social: Diseño, Cobertura y Financiamiento, 1st ed.; Organización Internacional del Trabajo: Santiago, Chile, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme, Q. Políticas de Estado y agricultura campesina. In Con la Soja al Cuello 2016. Informe sobre Agronegocios en Paraguay; Palau, M., Ed.; Base Investigaciones Sociales: Asunción, Paraguay, 2016; pp. 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme, Q. Programas y proyectos para la agricultura campesina. In Con la Soja al Cuello 2017. Informe sobre Agronegocios en Paraguay; Palau, M., Ed.; Base Investigaciones Sociales: Asunción, Paraguay, 2017; pp. 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Foro Internacional sobre Agroecología (FIA). Declaración del Foro Internacional sobre Agroecología; Nyéléni, Mali. 27 February 2015. Available online: https://viacampesina.org/es/declaracion-del-foro-internacional-de-agroecologia/ (accessed on 14 May 2019).

- Pacheco, M.E.L. Em defesa da agricultura familiar sustentável com igualdade de gênero. In Perspectivas de Gênero: Debates e Questões Para as ONGs; GT Gênero—Plataforma de Contrapartes Novib/SOS Corpo; Gênero e Cidadania: Recife, Brazil, 2002; pp. 138–161. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). L’agro-Ecologia può Aiutare a Migliorare la Produzione Alimentare Mondiale. Available online: http://www.fao.org/news/story/it/item/1113664/icode/ (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Dirección General de Estadísticas, Encuestas y Censos de Paraguay (DGEEC). Principales Resultados EPH 2013. Encuesta Permanente de Hogares; DGEEC Publicaciones: Fernando de la Mora, Paraguay, 2014; p. 191. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/surveydata/index.php/catalog/332/download/3416 (accessed on 28 April 2019).

| Themes | Analyzed | Not Analyzed |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainability Dimension G: GOOD GOVERNANCE | ||

| G1 Corporate Ethics | ✓ | |

| G2 Accountability | Not analyzed due to the low availability of data. | |

| G3 Participation | ✓ | |

| G4 Rule of Law | Not analyzed due to the low availability of data. | |

| G5 Holistic Management | Not analyzed due to the low availability of data. | |

| Sustainability Dimension E: ENVIRONMENTAL INTEGRITY | ||

| E1 Atmosphere | ✓ | |

| E2 Water | ✓ | |

| E3 Land | ✓ | |

| E4 Biodiversity | ✓ | |

| E5 Materials and Energy | ✓ | |

| E6 Animal Welfare | This theme has not been analyzed since not all the farms taken into consideration breed animals. | |

| Sustainability Dimension C: ECONOMIC RESILIENCE | ||

| C1 Investment | ✓ | |

| C2 Vulnerability | ✓ | |

| C3 Product Quality and Information | This theme has not been considered since in most cases, the products are sold in their natural state, so there are no processing, labeling and traceability systems. | |

| C4 Local Economy | ✓ | |

| Sustainability Dimension S: SOCIAL WELL-BEING | ||

| S1 Decent Livelihood | ✓ | |

| S2 Fair Trading Practices | ✓ | |

| S3 Labour Rights | ✓ | |

| S4 Equity | ✓ | |

| S5 Human Safety and Health | ✓ | |

| S6 Cultural Diversity | ✓ | |

| Agricultural System | Number of Farms Analyzed | |

|---|---|---|

| Agribusiness | 3 | |

| Peasant family farming and indigenous agriculture | Agro-ecological peasant family farming | 3 |

| Conventional peasant family farming | 3 | |

| Neo-rural agriculture | 3 | |

| Indigenous agriculture | 3 | |

| Analyzed Farm | Location | Extension (ha) | Crop | Livestock | Employees | Family |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | No. | |||||

| Agribusiness | ||||||

| 1A | Piribebuy | 900 | sugar cane | _ | 200 | 0 |

| 2A | San Juan Bautista | 6 | rice | _ | 10 permanent/100 casual | 0 |

| 3A | Yby Yau | 4 | soy and corn | Cattle | 4 | 1 |

| Agroecological peasant family farming | ||||||

| 1B | Altos | 80 | Cassava, beans, corn, potatoes, tomatoes, peppers, oranges, grapefruit, cucumbers, pumpkins, papaya, maracuja | Cattle, pigs, hens | 0 | 10 |

| 2B | Itauguá | 5 | Cucumbers, lettuce, mango, mandarins, oranges, eggplants, tomatoes, cassava, peppers, courgettes, carrots, rocket, and bananas. | Cattle, hens | 4 | 1 |

| 3B | Ypacarai | 10 | Tomatoes, peppers, corn, cassava, lettuce, beans | Cattle, hens | 0 | 1 |

| Conventional peasant family farming | ||||||

| 1C | Piribebuy | 0.75 | Tomatoes, peppers, corn, cassava, beans (for selling); fruit, pumpkins, nuts, aromatic herbs, onions (for self-consumption) | Pigs, hens | temporary employed if necessary | 1 |

| 2C | Chololó | 0.12 | Peppers (for selling); cucumbers, lettuce, tomatoes, parsley, onions (for self-consumption) | _ | 0 | 1 |

| 3C | Piribebuy | 4 | Cassava, corn, beans, origan, sorghum | Cattle, pigs, hens | temporary employed if necessary | 1 |

| Neo-rural agriculture | ||||||

| 1D | Luque | 1 | Lettuce, bananas, parsley, rocket, carrots tomatoes, lemons, papaya. | Pigs, hens | 2 | 1 |

| 2D | Aregua | 10 | Carrots, peppers, lattuce, eggplants, cabbage, persley, rocket, basil, sugar cane, soy, garlic, spinach, potatoes, corn, tomatoes, beet, chili pepper, onion, strawberries, papaya, maracujá. | Pigs | 2 and several volunteers | 1 |

| 3D | Encarna- ción | 5 | Carrots, peppers, tomatoes, rocket, basil, cabbage, beans, chili peppers. | _ | 3 | 1 |

| Indigenous agriculture | ||||||

| 1E | Capitan Bado | 2 | Oats, corn, beans, cassava, peanuts, potatoes, pumpkins, rice, lettuce, tomatoes, carrots, chickpeas, zucchini, beets, lentils, watermelons, honey, mate grass and medicinal herbs. | Domestic and woodland animals | 0 | 400 people |

| 2E | Capitan Bado | 1 | 0 | 100 people | ||

| 3E | Capitan Bado | 500 | 0 | 350 people | ||

| Agribusiness | |

|---|---|

| Good Governance | |

| Corporate Ethics | The company’s mission is not focused on sustainable development, but rather on maximizing the production. |

| Participation | Difficult identification and participation of all stakeholders, since the work is entrusted to third parties. |

| Environmental Integrity | |

| Atmosphere | Use of machinery and chemicals. |

| Water | In 1A and 3A, the crops are not irrigated. In 2A, the water is taken in abundance from neighboring water bodies in order to irrigate the plantation. |

| Land | 1A has organic and conventional cultivation. It does not use highly contaminated chemicals and uses distillery residues to supply minerals to the soil. 120 t/ha yield. Due to the exploitation of the soil, the yield of 2A over the years has changed from 13/14 to 8/9 t/ha. 2A and 3A use chemical fertilizers and pesticides, fumigating 10 times for 2A and eight times per cycle for 3A. 3A uses the sod-seeding technique, and seeds are treated with chemicals. Soil analysis determined the amount of fertilizer to be used. 1A leaves the land one green manure crop every five years, while 2A and 3A never do. |

| Biodiversity | Large-scale monocultures. 3A interchanges soy with corn at each cycle. |

| Materials and Energy | Material recycling. In all cases, cultivation is mechanized. To prevent the deforestation of native plants for the use of timber, 1A own a eucalyptus plantation, whose wood is used as combustible. |

| Economic Resilience | |

| Investment | Moderate long-term investment in experimentation for sustainable agriculture. |

| Vulnerability | Adoption of own strategies to mitigate internal and external risks, as they do not have insurance. |

| Local Economy | Production for export. Regional workforce. |

| Social Well-Being | |

| Decent Livelihood | In 1A, the work shifts are heavy, the workers earn minimum wage, and overtime is not adequately paid. Refresher courses are organized for their employees. In 2A and 3A, the work is not heavy. |

| Fair Trading Practices | In 1A, the 200 daily workers in the plantation were paid for piecework and did not have regular contracts. 2A has 10 permanent workers and 100 casual workers. The permanent employees have a regular contract, while the daily workers not. 3A has four permanent workers with specific training. |

| Labour Rights | 1A hinders trade union struggles, penalizing those who seek to claim their rights. |

| Equity | 1A also employs women and disabled people according to social policies. |

| Human Safety and Health | Social and medical insurance only exists for permanent workers, such as agronomists and machinery operators. |

| Cultural Diversity | Use of modern knowledge and technology. |

| Agroecological Peasant Family Farming | |

|---|---|

| Good Governance | |

| Corporate Ethics | Company mission aims at sustainable practices through the application of the principles of agroecology. |

| Participation | Each company member contributes to the community and takes part in the decision-making process. |

| Environmental Integrity | |

| Atmosphere | No machinery is used; air quality is not affected. |

| Water | In 1B, the crops are not irrigated. In the absence of rain in 2B and 3B, the garden is irrigated every day through a drip irrigation system and a sprinkler. The water is taken from an artesian well, which everyone can use for two hours a day. In all cases, part of the cultivation is protected from the sun by shading nets. |

| Land | Various techniques such as crop rotation, compost, manure, vegetation cover, associated cultivation, legume green manure, synthetic fertilizers, and biological pesticides are used. Aromatic plants and fruit trees act as a dividing barrier between the various plots of land so that pests do not invade cultivation. Plastic mulch is used to prevent weed growth, keep soil moisture, and protect the soil from erosion. |

| Biodiversity | A wide variety of vegetables and fruits are cultivated. The farms also raise cows, pigs, and chickens from which milk, cheese, meat, and eggs are obtained for self-consumption. In addition to the land used for agriculture, there are native woods, courses, and water springs. |

| Materials and Energy | The residues generated by agricultural work are reused. The work is mainly manual. During the preparation of the soil, a small mechanical plough is used in 2B, while 1B uses ox-drawn plows. |

| Economic Resilience | |

| Investment | Production is supervised by technicians and agronomists who successfully plan and manage the company. |

| Vulnerability | Great diversity of production and various cultivation strategies. |

| Local Economy | The workforce is regional, and the cultivated products are destined for self-consumption and for extremely close trade. |

| Social Well-Being | |

| Decent Livelihood | Workers’ rights are respected through appropriate working hours, leaving room for rest, family, and home care. |

| Fair Trading Practices | The agricultural work is carried out by the members of the family, and when necessary, occasional workers are hired; in 2B, in addition to the family members, four people from the area work permanently on the farm. |

| Labour Rights | There are no real “employee–employer” links, but there are solidarity ties between family members. Minga, mutual help in the garden, is practiced. In their free time, children help in the garden to learn traditional techniques. |

| Equity | Men and women take part in the production process. |

| Human Safety and Health | The members of the community do not have social and medical insurance, but the companies are provided with a first aid kit to deal with minor injuries. |

| Cultural Diversity | Farms exchange and grow native seeds by encouraging the cultivation of locally adapted varieties of the local diet. |

| Conventional Peasant Family Farming | |

|---|---|

| Good Governance | |

| Corporate Ethics | Companies do not have a mission clearly focused on sustainable development. |

| Participation | The members of the farms are part of committees, and all the workers take part in the decision-making process. In 1C, the owner was the promoter of a committee of women, and now she is the treasurer; in 3C, the head of the family is the chairman of a committee. |

| Environmental Integrity | |

| Atmosphere | No machinery is used; air quality is not affected. |

| Water | In 1C, the garden is irrigated manually with a hose or by sprinkler twice a day, while the field depends on the precipitation. Where the garden is sloping, terraces with plastic bottles have been built in order to reduce water loss. 2C uses drip irrigation. In 3C, crops depend on rain, and for this reason, drought-resistant varieties are cultivated. In all cases, shading nets are used to protect the vegetables from the sun. |

| Land | Crop rotation and associated cultivation is used. To fertilize the land poultry, ash and compost from food residues and chemicals are used. In order to keep pests under control, synthetic pesticides, manure, and alcohol-based herbal solutions are used. Plastic mulch is used in order to prevent the growth of weeds, keep the soil moisture, and protect the soil from erosion. |

| Biodiversity | Generally, the production is diversified between the products for sale and those for self-consumption. Different varieties of vegetables and fruits are cultivated. Hens, cows, and pigs are raised for the production of milk, cheese, eggs, and meat for self-consumption and for sale in the local market. |

| Materials and Energy | The work in the garden is mainly manual. In 2C, a portable motor plow is used, and in 1C and 3C, vegetable residues are used for feeding animals or to make compost. |

| Economic Resilience | |

| Investment | 1C would like to make an investment to improve the irrigation system but cannot access an agricultural credit because the holder has exceeded the 60-year threshold, a term beyond which the loan is not granted. 2C has invested about $1500 in shading networks, a motor, and a tank for the drip irrigation system. |

| Vulnerability | Collaboration with the agronomists of the Ministry of Agriculture in order to acquire useful techniques for the success of the production. In 2C, some tools were supplied to the company thanks to a project by the Ministry of Agriculture |

| Local Economy | Production is aimed at self-consumption and local sales. Regional workforce. |

| Social Well-Being | |

| Decent Livelihood | The work is not heavy. |

| Fair Trading Practices | There are no real and proper working relationships, putting into play family dynamics based on solidarity and reciprocity. |

| Labor Rights | There are no real and proper working relationships, putting into play family dynamics based on solidarity and reciprocity. |

| Equity | Women play an important role by participating in agricultural work or managing the company’s income. |

| Human Safety and Health | Workers do not have social and medical insurance. Hospitals can be easily reached by public transport, and there are first aid kits available on the farms. |

| Cultural Diversity | Foods grown are part of the local diet following ancestral traditions. |

| Neo-Rural Farming | |

|---|---|

| Good Governance | |

| Corporate Ethics | Farms’ aims include leading a healthy life and cultivating products while respecting the environment. |

| Participation | All workers take part in the decision-making process of the company, are mindful of committees, and participate in meetings. |

| Environmental Integrity | |

| Atmosphere | No machinery is used; air quality is not affected. |

| Water | 1D has two pools that are filled with rainwater, which is taken to irrigate the garden. Shading nets are used to protect crops from the sun. 2D has a well, a reservoir, and a large pool where rainwater is collected. |

| Land | These are agro-ecological farms for which no chemical fertilizer or insecticide is used. To increase the fertility of the soil, natural remedies are used such as legume green manure, compost with garden residues, crop rotation, and associated cultivation. Plastic mulch is used in order to prevent the growth of weeds, maintain the moisture in the soil, and protect the soil from erosion. |

| Biodiversity | A wide variety of vegetables and fruits are cultivated. In 1D and 2D, some pigs and hens are bred for the production of meat and eggs. 1D is also dedicated to the cultivation of aromatic and ornamental plants. |

| Materials and Energy | Food waste is avoided, and materials recycling is encouraged. In 1D, the surplus food is sold at lower prices or donated, supplied as food to the animals, or used as compost. Agricultural work is mainly manual. 3D has a machine for shredding leaves in order to obtain a compost and a small portable plow. For market sales, reusable wooden, plastic, and polystyrene boxes are used. |

| Economic Resilience | |

| Investment | 2D plans to buy more land, install an irrigation system, give the estate a focus on eco-sustainable tourism, and find new marketing channels. |

| Vulnerability | 1D does not have access to funding from the State, but in case of need relies on informal financial sources. The family has other sources of income: the garden is seen mainly as a source of self-consumption and small trade to support the costs of land management. The agricultural work in 2D does not allow covering the costs of the production; however, the company supports this method for the intrinsic value of the agroecology. 3D has been active for two years, and only recently began to make profits, supporting itself thanks to its own financial resources. |

| Local Economy | Production for self-consumption and trade in local markets and through a home delivery service. 2D is based on the voluntary work of young people, especially Europeans, who spend a period in the structure—on average between two and three weeks—to dedicate themselves to agricultural work in exchange for food and lodging. Upon arrival at the facility, the young volunteers receive training and are supported during work. Farms generally sell their products at a slightly lower price than in the supermarket in order to educate the consumer to recognize the quality and taste of organic products. |

| Social Well-Being | |

| Decent Livelihood | Workers have time for rest, family, and culture, earning at least the minimum wage. |

| Fair Trading Practices | Companies are based on fair trade. In 1D, the staff is composed of a married couple and two permanent workers, and when needed, they are helped by friends and relatives. 2D is run by a young couple from Asunción where two employees and various foreign volunteers work. In 3D, a family hired by the owners takes care of the garden. |

| Labour Rights | In 2D, the staff works from 06:00 to 11:00 in order to take advantage of the coolest hours of the day and be able to dedicate the rest of the time to other activities. The owners of the company have a university education in biology and agricultural administration. |

| Equity | Men and women take part in the production process equally. |

| Human Safety and Health | Companies provide medical insurance to their workers. |

| Cultural Diversity | The seeds are exchanged with other small producers, keeping the local varieties alive, stimulating food sovereignty, and allowing a healthy diet. |

| Indigenous Agriculture | |

|---|---|

| Good Governance | |

| Corporate Ethics | Communities aim at safeguarding and respecting the environment; nature is considered sacred by the natives, and is seen not only as a means of production but as a space for social and religious life: the earth, the woods, and the waterways belong to the whole community, so everyone must work to their protection and conservation. |

| Participation | The extended family is the unity of the indigenous society within which decisions are made. The elderly are the heads of the family group, and men and women share the decision-making process and responsibilities. |

| Environmental Integrity | |

| Atmosphere | No machinery is used; air quality is not affected. |

| Water | Crops are not irrigated, and the soil is covered with leaves and garden residues in order to maintain humidity. |

| Land | Maintaining the quality of the soil, the communities resort to leguminous green manure, crop rotation, and associated cultivation, periodically leaving the earth to rest. |

| Biodiversity | High genetic variability of cultivated products. |

| Materials and Energy | Lacking running water and electricity, wood serves as the sole source of energy. |

| Economic Resilience | |

| Investment | Families are investing in buying mobile phones and motorcycles to improve communication and transports. |

| Vulnerability | The availability of food from agriculture fluctuates during the year and is significantly affected by climatic conditions, so the consumption of its products is low during the winter months, with the exception of cassava, which is the main basis of the community’s indigenous diet along with corn, which can be kept for long periods. |

| Local Economy | Food for self-consumption, where excess products are exchanged with other goods or sold in local markets or at the agroecological market in the capital. |

| Social Well-Being | |

| Decent Livelihood | The work is not too heavy, leaving room for the family and leisure time. |

| Fair Trading Practices | The principle of mutual aid and reciprocity among the members of the community is called jopói and consists of an exchange of goods and favors, in which the return is not necessarily immediate. |

| Labour Rights | There are no real “employee–employer” working links, but there are solidarity ties between family members. |

| Equity | According to the social organization, men are dedicated to hunting and preparing the land, while women are involved in sowing, harvesting, preparing food, and economically administering the family. |

| Human Safety and Health | Families do not have medical insurance, are wary of public health, and are treated according to their ancestral knowledge. |

| Cultural Diversity | Agriculture is based on ancestral knowledge. Use native species that are part of the local diet. Agricultural work is carried out following a lunar and seasonal calendar; the production process is linked to a series of religious rites. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soldi, A.; Aparicio Meza, M.J.; Guareschi, M.; Donati, M.; Insfrán Ortiz, A. Sustainability Assessment of Agricultural Systems in Paraguay: A Comparative Study Using FAO’s SAFA Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133745

Soldi A, Aparicio Meza MJ, Guareschi M, Donati M, Insfrán Ortiz A. Sustainability Assessment of Agricultural Systems in Paraguay: A Comparative Study Using FAO’s SAFA Framework. Sustainability. 2019; 11(13):3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133745

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoldi, Alice, Maria José Aparicio Meza, Marianna Guareschi, Michele Donati, and Amado Insfrán Ortiz. 2019. "Sustainability Assessment of Agricultural Systems in Paraguay: A Comparative Study Using FAO’s SAFA Framework" Sustainability 11, no. 13: 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133745

APA StyleSoldi, A., Aparicio Meza, M. J., Guareschi, M., Donati, M., & Insfrán Ortiz, A. (2019). Sustainability Assessment of Agricultural Systems in Paraguay: A Comparative Study Using FAO’s SAFA Framework. Sustainability, 11(13), 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133745