1. Introduction

When examining the sustainable nature of a thematic tourist trail, which is the main objective of this publication, it is impossible to omit the context of the sustainable development idea in tourism. The concept of sustainable tourism, or rather sustainable development, has been present in tourism for several decades [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Simultaneously, an increase in the threat posed by mass tourism to the environment has been observed [

8,

9]. Significant elements of sustainable tourism are included in the postulates of alternative tourism. Alternative tourism stands in opposition to mass tourism, which clearly interferes, in a negative way, in the natural environment. The proposal that is expected to change this reality is to find an alternative to such a situation. The starting point for Krippendorf [

10] is the community. In his opinion, alternative tourism is rather a social movement; its main objective is to popularize the forms of tourism which minimize the economic costs of practising it, especially the ecological and social ones. Szwichtenberg [

11] or Baczwarow [

12] treat it more as a philosophy of activity, where the essence is the minimum possible interference in the natural environment. Like others, they stress the need for appropriate contact with both nature and the local community. The main trend of alternative tourism in the last decades of the previous century involved the idea of ecotourism or green tourism.

Tourisme vert [

13], respecting nature, puts it in the first place. According to Szwichtenberg [

11], Shepherd [

14], Krider et al. [

15], and Fennell [

16], ecotourism includes all forms of tourism which relate properly to tourist values, especially those of the natural environment. The superior objective should be to act in accordance with the letter of the law in conditions of full ecological ethics and at every stage of its implementation. Zaręba [

17] considers ecotourism as a form of active tourism which allows us to discover areas of outstanding natural and cultural value. Ecotourism is the guardian of the harmony of natural ecosystems. Czerwiński et al. [

18] emphasize the role of ecotourism in shaping the environmental awareness both among participants and organizers of the tourist traffic. The concept of sustainable development is also present in responsible tourism. Responsible tourism [

19,

20,

21,

22] underlines minimum interference with the natural environment and respect for the cultural identity of the areas visited, which should result in increased satisfaction with tourism [

23]. Wheeler [

19] stresses that local communities must participate in the development of this form of tourism. The development should be small-scale, slow, and controlled [

24]; both the tour operator and their client should be aware of this [

25,

26].

The very concept of sustainable tourism appeared in the last decades of the previous century [

10,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

Inskeep [

31] developed the idea of sustainable tourism in quite a detailed way, indicating its most important features. It is based on an attempt to find a balance [

35] between the needs of the recipient of a tourist product offer and the product creator on the one hand, and, on the other, the need to preserve the natural (as indicated earlier) and cultural environment (whose stability appears equally fragile) exploited by the tourist [

36]. Therefore, it is crucial that tourism, in the context of its sustainable development, considers the cultural and natural specificity of a region, adapting to its opportunities and limitations. The primary objective should be such action on the part of the authorities and the local community that the natural environment remains relatively unchanged for future generations [

37]. Thus, an analysis of the costs associated with the tourist activity in a given area should take into account not only the current situation, but also future consequences. It is also important that the costs and benefits of this activity should be equally divided between tourists and the local population, who should be involved as much as possible in the activity organization and the benefits it generates [

38]. The first step taken in the context of sustainable development should be to assess the impact of these measures on the natural and cultural environment in order to eliminate, from the very beginning, the ones which could adversely affect the environment. The quality of the environment and the quality of the local community life are important [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

The participants of the world conference on sustainable tourism, whose postulates are included in the Charter for Sustainable Tourism, spoke in a similar way. The postulate stresses taking into account the durability of the natural environment functioning in a region of high tourist attractiveness, as well as links with the local economy. However, the importance of adjusting, in terms of ethical and social standards, all activities related to the creation of tourist products to the norms binding in a given community is also emphasized. Mutual respect and broad cooperation among all tourism stakeholders are considered prerequisite sfor commercial success in the context of sustainable activities [

44,

45]. The need is underlined to develop an appropriate mechanism for cooperation between authorities and institutions at all levels, from the local, through regional, to international ones [

37,

46,

47,

48].

The objectives of sustainable tourism are often referred to in literature [

31,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. In fact, they can be overall perceived as a concept of respect. This is a key word which relates to natural and cultural resources and it is difficult to indicate in which case it is more important. Respect for nature seems to be obvious through the prism of years of ecological education and clear changes in the environment resulting from non-compliance with its principles. In the cultural context, however, it is more difficult to grasp the meaning of this approach. Cultural changes under the influence of globalization, with tourism playing a significant role, are more difficult to perceive and in fact it is too late when their effects become visible. Hence the postulated need [

54] is for local culture to be treated with special care by both the local community and tourists, who should be a catalyst for these attitudes. It is about respect for identity and understanding local traditions and lifestyles of local communities, while taking advantage of the economic opportunity offered by this attitude to the region of tourist interest [

55,

56].

In the case of sustainable tourism, the socio-economic development of the local community is as important as the protection of natural resources; community welfare should not be sacrificed for the purposes of strict protection. It is an eternal problem between the maximum need for nature protection and the desire to learn the values which, after all, constitute a common good. Therefore, another crucial word defining the phenomenon of sustainable tourism is harmony. Sustainable development runs without further damage to the area resources and remains compatible and harmonious with nature and the surrounding world with its cultural potential [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. It is important that it is a small-scale activity, thus friendly to the natural environment and local communities. The minimalist approach indicates the lack of negative consequences in the natural and social environment. Such actions can be considered sustainable. For Lane [

62], sustainable tourism is merely or as much as a term used to identify the principles, laws, and management methods that indicate the path of tourism development in areas rich in natural and cultural resources in the context of their simultaneous protection [

32,

63]. A good summary is the thesis put forward by Kowalczyk [

64], who defines sustainable tourism as a phenomenon in which activities undertaken by tourists do not cause losses or irreversible changes in the natural environment, at the same time bringing benefits to tourists themselves, to communities living in the visited towns and areas, and to persons and institutions providing tourist services.

Among the key challenges to sustainable tourism, examples are reducing the seasonality of stay, maintaining and improving the well-being of local communities, and ensuring access to tourism for all social groups [

65,

66,

67,

68]. A thematic trail, one of the concepts most important for sustainable development of a region, especially in rural areas, perfectly fits into the above postulates.

A thematic trail brings together different values linked by a common theme, with appropriate infrastructure [

69]. According to Kruczek [

70], it is a route marked in a tourist space leading visitors to the most attractive places, not always signed. Thematic trails can be found in a variety of landscapes, both urban and rural. They also vary in scale: from local to international. Regardless of the advantages and scale, trails are initiated with one or more of the following objectives: to diffuse visitors and disperse income from tourism; to bring lesser known attractions and features into the tourism business/product; to increase the overall appeal of a destination; to increase the stay and spending by tourists; to attract new tourists and repeat visitors; and to increase the sustainability of the tourist product [

71].

1.1. Thematic Tourist Trail as a Tool of Sustainable Development: Trail Scheme

The main objective of this study is an attempt to determine, on the basis of the proposed methodology and indices, to what extent a thematic tourist trail implements the idea of sustainable development in tourism. In order to find an answer to this question, one should first try to establish which of the elements shaping the thematic trail tourist offer have an impact on its sustainable functioning. The next step is to try to determine the sustainability of a specific trail. We chose to investigate the thematic trail of the Land Flowing with Milk and Honey in Lower Silesia, south-western Poland. Below is a brief overview of its potential. This is the first trail which derives its attractiveness from the idea of sustainable development, so it is even more worth checking how faithful it remains to the concept.

In order to estimate to what extent a thematic trail is sustainable in its nature, it is necessary to first point to the elements that constitute the concept of sustainable development in the context of tourism. Within this concept, one of the main problems faced by researchers and professionals creating a tourist product is the appropriate use of resources that form the basis for the tourist offer. This concerns both natural and cultural resources. One of the most popular products integrating tourism in the region on the basis of its characteristic resource is the thematic trail.

Taking into account the elements typical of a thematic tourist trail, it is possible to propose a model of functioning of a sustainable thematic trail, indicating its essential elements. These are:

The main element of the trail: the product, a binding agent, the overarching idea combining the elements that make up the trail. Such a product must be characteristic of the region. The product features that make it sustainable are as follows:

Origin. in the region. The product should be made with techniques typical of the region and based on local traditions. This is emphasized in various forums, including the European Union [

72].

Range. The product must be characteristic of a specific place or region. The following dependence is crucial: the smaller the range, the greater the tourist attractiveness of the product. This results from a simple assumption: the more unique the good, the more willing a tourist will be to take a trip to benefit from it.

Producer. Attractiveness is a derivative of locality. If a product is manufactured by a local community, the community is provided with the profits and economic benefit. This also translates into their greater care to preserve and cultivate this value because, besides the deposit of tradition, it is also their source of income. The ideal situation is when the owner and distributor of a product is at the same time its manufacturer, and the main place of distribution is the place of production. It can therefore be assumed that the more local the product is, the higher its sustainability.

Raw material. The product’s attractiveness is greater if the raw material used for production is local or regional.

A certificate held by the product, issued by a relevant institution. An appropriate certificate raises the rank of the sustainability of the trail and its co-creating elements. There exist two types of certificates:

tourist, pointing at the quality of a tourist product;

sustainable, indicating the product’s weight in terms of its sustainability.

Certificates can be ranked according to their range: international, national, and regional/local. The higher the rank, the higher the weight of the trail and its elements as tourist products. The number of certificates is also important. Sometimes one trail element holds more than one certificate, which strengthens the rank of the place and trail.

- 3.

The thematic trail as a real tourist product. An important element constituting a sustainable thematic trail as a tourist product is the tourist function that it performs. It should be assessed as to what extent particular trail elements fulfil the tourist function and what tourist services they offer. Depending on the degree of tourist function development, one can differentiate between: a simple service, i.e., the sale of a product at the manufacturing site; sale of a product combined with catering services; sale of a product combined with interpretation; sale with interpretation and catering services; sale combined with accommodation services; sale with interpretation and accommodation services; and sale combined with interpretation and catering and accommodation services.

- 4.

The stay attractiveness index—an element associated with the previous point—which translates into the potential duration of product use. It is a derivative of the wealth of the complementary offer, including visiting a museum, attending classes and their duration, and accommodation possibilities. The index is based on a declaration of the offer organizer, who specifies the duration of the lessons and of the guided and unguided sightseeing. It reaches its maximum value if the offer involves accommodation and catering facilities.

- 5.

Tourist cohesion of the trail. It depends on the extent to which the trail is a fully tourist product. It may happen that not all elements constituting the trail fulfil the tourist function to any degree. Therefore, it is necessary to check whether each trail site is available for tourists. It seems that the specific ‘tourist holes’ in a trail should be avoided, and they definitely cannot directly follow one another, as this would arouse an unwillingness to further travel along the trail.

- 6.

Participation of local authorities. This is an important factor stabilizing trail operation, and is important for its sustainability. Local authorities, with specific knowledge of the region, local culture, etc., will take much better care of the value or tourist product than higher-level authorities. The support of self-government authorities may be active or passive. Passive support is limited to advocating the idea, possibly expressed with a permission to use the institution as a patron. Active support may manifest itself at different levels: as financial or logistical support, quality control, or a combination of these elements.

- 7.

Participation of associations, local action groups, etc. This is as important as the involvement of the authorities. Persons and entities should be involved who are directly interested in the proper functioning of the trail on the basis of resources. The participation of NGOs is also essential, as they most fully express the interest of the local community by taking care of sustainable activities.

- 8.

Promotion. It is important to use the ‘eco’ or ‘sustainability’ element in promotion in real or virtual space when informing about the product which is a part of a thematic trail.

- 9.

The organiser/coordinator of the trail should be known for their sustainable, ecological activities, resulting in a sustainable use of natural and cultural resources in tourism.

- 10.

Relationship of a particular trail element with other trails or tourist initiatives. This undoubtedly strengthens its tourist attractiveness and recognition in the region.

1.2. The Trail of the Land Flowing with Milk and Honey

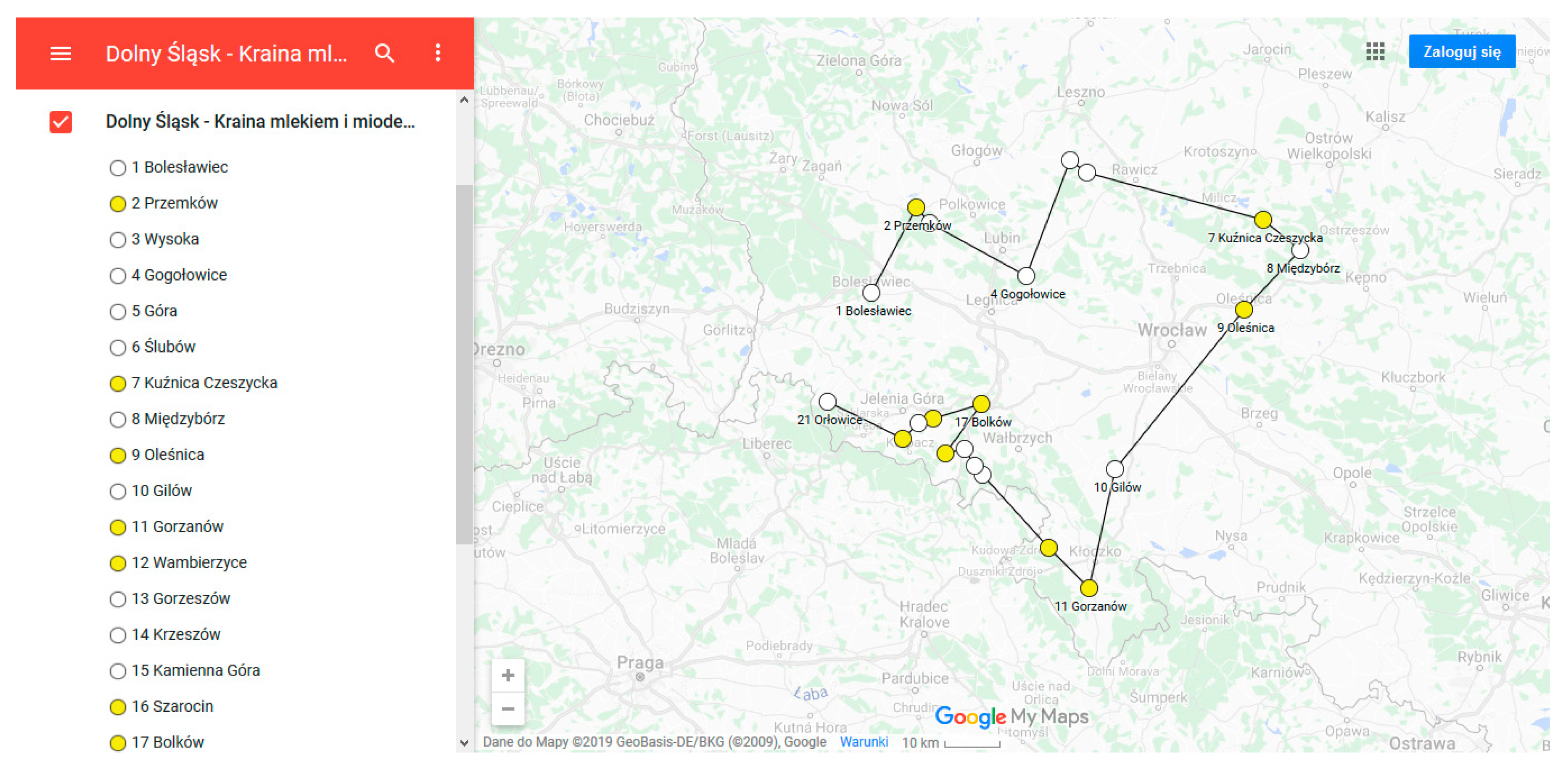

The Land Flowing with Milk and Honey (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) trail is a thematic trail in Lower Silesia, in south-western Poland. It focuses on economic activities related to dairying and beekeeping.

Its course refers to the main idea, which is to present the potential of the region in a sustainable way, as declared by the main coordinator of the trail in an interview. The particular stops on the route offer various types of tourist products: from simple sale, through getting to know the process of creating regional products in a passive or active form, to the possibility of a longer recreational stay.

The presence on the trail almost always assumes interaction with representatives of the local community. These are often the owners or managers of an offer that is presented to visitors. The organisers themselves address the offer to their recipients in the following way: “On the way, you will see busy workshops and peaceful rural farms. You can try fresh milk, fragrant cheeses, just extracted honey, and all other delicacies of cow, goat, and bee. The welcoming hosts will tell you about the secrets of their craft. They will show and teach you what real honey is and that there are more types of cheese than all the colours of the Lower Silesian summer” [

74].

1.3. Trail Coordinator

Although the particular stops on the trail are marked with the logo of the main manager and organiser in terms of logistics, i.e., the Green Gate association (

Figure 5) and the Academy of Sustainable Living, the basic place of presentation is virtual space. As emphasized in the introductory description, the course of the trail is indicated on a map provided on the organization’s website using Google Maps resources, accompanied by a description of the trail attractions.

The description is not complex. Each attraction is presented in a short passage of 100–400 words. This general report indicates the characteristic sites and their association with the main theme of the trail. Then, the basic data of a site are provided: the name of the company or the main owner, who is also the contact person, the attraction address, contact telephone number, and, if any, website address.

The trail is presented in virtual space but the functionality is not quite properly implemented: in three cases, the link does not work. The trail comprises 22 sites in 21 locations (mostly villages, with four small towns).

The coordinator and creator of the trail is the Green Gate association, based in Kamienna Góra. Among the 29 statutory objectives of the association, it is worth mentioning those that particularly refer to the trail character: to promote the principle of sustainable development and ecology; to promote the natural and ecological cultivation of traditional plant varieties and husbandry of animal species traditional for the region; to promote the Sudetes region and improve its tourist value; to promote the protection of cultural heritage; to promote the creation and development of civil society; to strengthen links between the local community and the region and to preserve tradition; to activate rural areas; to promote equality between women and men; to work for those at risk of exclusion; to counteract unemployment; and to promote knowledge in the field of information technologies and access to the Internet [

75]. All these postulates refer to the idea of sustainable development of the region.

The objectives are achieved through the following: building the Academy of Sustainable Living as an educational, workshop, manufacturing, and catering base; popularization, promotional, and tourist activities; supporting ecological farming; initiating and conducting various forms of tourism, including qualified tourism; promoting and manufacturing local products; and promoting the culinary traditions of the region. The activation of rural areas, especially the Sudetes region, is crucial.

The association has a training and workshop centre for educational activities for different age groups. With the focus on teaching in the open air, the Academy has four hectares of meadows at its disposal. There is an educational apiary and an educational path with nectar source plants. Illustrative lessons on beekeeping are held, with the opportunity of honey tasting.

1.4. Trail Elements

The starting point of the trail is the Ceramic Plant in Boleslawiec. It is one of the largest manufacturers of handmade ceramics ornamented with a unique regional stamping technique. The trail character, associated with honey and milk, is referred to in these two sentences: “Honey and milk in cups from Bolesławiec taste delicious. Just like centuries ago!” Certificates: ISO 9001:2000 quality management system, Regional Eagles of Exports, and Lower Silesian Gryphon. Tourist function: very limited. Occasional group sightseeing tours are possible. In the company shop, the manufactured products are sold.

Another stop on the trail is Przemków, a town belonging to the ‘Heather Land’ Local Action Group, whose branded product is heather honey. There are two beekeeping farms within the trail. One of them is the Młynowo apiary. The honey produced here has the European certificate of Protected Geographical Indication (PGI). It was also featured on the national List of Traditional Products (LTP). Tourist function: limited. In the farm shop, products like honey and wax are sold.

Przemków: the ‘Maja’ apiary, conducted since 1977. The main product is heather honey (PGI and LTP certificates), but also wax and candles. Tourist function: extended. Local products are sold in the farm shop. Interpretation: participation in workshops on casting candles made of beeswax and educational presentations related to beekeeping, possibility to benefit from apitherapy.

Wysoka: a certified ecological ‘Raspberry Farm’ (Malinowa Zagroda). Ecological production of raspberries, currants, and vegetables. The main attraction: production of cheese from goat milk based on medieval Cistercian traditions. Tourist function: sale of products, mainly cheese.

The Chudzińskis’ goat farming in Gogołowice near Milicz. The products are manufactured on the basis of own production, with traditional tools and traditional techniques. The farm is located within the area of activity of the ‘Partnership for the Barycz Valley’ Local Action Group. Certificates: ‘The Barycz Valley Recommends’ quality certificate.

Góra: a ‘Demi’ dairy cooperative. Production started in 1900. The preservation of traditional methods of making milk products is emphasised. The main product is the hand-made Górowski cheese. National ‘Appreciate the Polish’ quality certificate. Tourist function: sale of products in the company shop.

Ślubów: the ‘Cheeses of Ślubów’ (Sery Ślubowskie) farmer processing plant. The raw material comes from a small family farm in the Barycz Valley, from ecologically clean areas, as emphasized in the description. Milk is inspected daily. The herbal and vegetable additives used in the production of cheeses come from farms that are certified in accordance with the relevant ecological standards. Production is based on traditional local recipes. Certificates: Culinary Heritage of Lower Silesia. Tourist function: sale of their own products.

Kuźnica Czeszycka: Wacław Ratyński’s ecological apiary, producing honey; over 60 hives. Certificates: Educational Farm certificate within the National Network of Educational Farms, ‘The Barycz Valley Recommends’ quality certificate; listed on LTP. Tourist function: an open-air museum with old hives even from the eighteenth century. The offer of three educational programmes: history of beekeeping, apiary farming, and bee products. Classes last from 3 to 5 h. The touring owner may serve a group of 30 people at a time.

Międzybórz: a Regional Dairy Cooperative producing butter and cheeses. Certificates: Culinary Heritage of Lower Silesia, Get to Know Good Food. Tourist function: sale of products in the company shop.

Oleśnica: the ‘Gingerbread Wonders’ (Piernikowe cuda) bakery. Here, gingerbread is produced on the basis of a traditional recipe. The products are manufactured and decorated by hand. Certificate: LTP. Tourist function: sale of products at the manufacturing site.

Gilów: the Reproduction Animal Husbandry Centre (Ośrodek Hodowli Zarodowej Przerzeczyn Zdrój Sp. z o.o.). Breeding of dairy cattle of the Polish red and white and Polish red breeds, beef production. Certificate: LTP. Tourist function: none.

Gorzanów: ‘Rosa’ apiary. Production of honey, wax, candles. The owner is a member of the Słomianka folk association. The aim is “to support the local folklore and disappearing professions, to promote the acquisition of knowledge and skills among local residents to improve their qualifications in the field of local crafts. They apply the local potential and knowledge, as well as the raw materials available and typical of the region for this purpose” [

76]. Tourist function: sale of products at the manufacturing site.

Wambierzyce: Piotr and Magdalena Kopacz’s apiary, operating since 1967. It produces honey, mead, propolis, and wax candles. Tourist function: products shop. Interpretation: active visit to the apiary: a close look at the honey production process in beekeeper’s clothing, mead tasting, and making wax products, especially an own candle.

Gorzeszów: the ‘Green Dream’ (Zielone Marzenie) ecological farm. The farm is engaged in ecological production. It has an ecological farm certificate. It offers goat milk products, vegetables, and seasonal fruit and vegetables produced ecologically, such as lettuce, spinach, or cucumbers. Tourist function: product sale. Interpretation: medieval cuisine workshops, farming.

Krzeszów: the ‘Wańczykówka’ ecological agritourist farm. The company deals with cow breeding and cheese production. Cheeses are handmade with the use of traditional technology and recipe. Certificates: ecological farm certificate, The Green Valley of Food and Health certificate, Slow Food Poland. The owners are members of the Farmer Cheesemakers Association. Tourist function: products sale. Interpretation: thematic workshops devoted to cheese production, conference facilities, and accommodation offer.

Kamienna Góra: the ‘KaMos’ Dairy Cooperative. The raw material for cheese production comes from local family farms. Certificates: Quality Tradition certificate, Global Quality—International Food Standard, Get to Know Good Food, LTP, Culinary Heritage of Lower Silesia. Tourist function: sale of products in the company shop.

Szarocin: the Green Gate association, Academy of Sustainable Living, Educational Apiary; described above as the organizer and coordinator of the whole project.

Bolków: a woodworking and sawmill plant. One of the largest hive producers in Poland and Europe. Certificates: Model Agri-Entrepreneur RP 2016. Tourist function: practically none.

Trzcińsko: ‘Sweet Cottage’ (Słodka Chatka) gingerbread production. Certificates: Slow Food Lower Silesia, ‘Treasures of the Mountain Spirit’ Karkonosze Local Brand. Tourist function: sale of products at the manufacturing site. Interpretation: gingerbread production ecological museum; thematic workshops devoted to gingerbread production.

Łomnica: ‘Goat Meadow’ (Kozia Łąka) ecological farm. Ecological production of cheese from goat milk obtained from their own goats (herd of about 100 goats). The manufacturing is based on traditional technology and traditional recipe. Certificates: National Network of Educational Farms, ‘Treasures of the Mountain Spirit’ Karkonosze Local Brand, ecological farm certificate, Culinary Heritage of Lower Silesia, The Green Valley of Food and Health certificate, LTP. Tourist function and interpretation: cheese-making ecological museum; workshops for individual tourists and groups of up to 50 people. The offer includes visiting the farm, feeding goats, competitions (e.g., in milking goats), tasting of cheese and cheese-based dishes, cheese-making workshops and shows, talks and mini-lectures about goats and cheeses. The farm is a member of the ‘Partnership of the Mountain Spirit’ Local Action Group and part of the culinary trail of Flavours of Lower Silesia.

Sosnówka: Klemens Koper’s ecological apiary. This is the first certified ecological apiary in Lower Silesia. It holds an ‘Ekogwarancja’ certificate of ecological apiary issued by the Polish Ecological Agriculture Society. Tourist function: own products sale.

Orłowice: Karol and Andrzej Wilk’s ‘Wild Beehive’ (Barć) family apiary. Tourist function: product sale.

1.5. Certificates on the Trail of Land Flowing with Milk and Honey

The potential of the trail sustainability is expressed by appropriate certificates (

Table 1). These are a specific guarantee of quality and regionality, particularly important for trail creation if sustainable development is the main success factor. Therefore, it is worthwhile taking a closer look at the potential of the trail in this respect. Depending on their range, certificates can be divided into international, national, or regional ones.

2. Material and Methodology

The analysed thematic tourist trail of the Land Flowing with Milk and Honey is an Internet trail, as emphasized by its creator and coordinator. Hence, the main assumption is that all information necessary for a potential tourist should be included in the trail description in the virtual space. Therefore, the entire analysis of the trail is based on information available on its official website and on the websites of its co-creating entities. The basic method of the trail inventory was the desk research method. First of all, the official website of the coordinator and the organizer of the trail, the Green Gate association, was analysed [

74]. It describes the activity of the organization. One of the tabs is devoted to the Lower Silesian thematic trail of the Land Flowing with Milk and Honey. In accordance with the assumption, the websites of the units included in the proposed trail were also analysed, provided that information about them was available. In most cases, at the end of each unit presentation, there is a link to its official website. On the basis of these websites, material was collected and further analysed. Additional, equally important information was obtained during an interview with Jarosław Giercarz, President of the Management Board. It concerned mainly the rules of the association functioning and the assumptions underlying the creation of the Internet thematic trail. The basic condition for inclusion in the trail was operating in accordance with the idea of sustainable and ecological development. The collected information was classified into selected categories, which were included in the description of the functioning model of a sustainable tourist trail. The main elements taken into account in the analysis were the following:

the regional product that constituted the basis for creating the tourist offer: its origin, range, raw material, and producer;

the quality certificate awarded to the regional products concerned, its nature and range;

the character of the tourist product created on the basis of the regional product;

the time that the potential tourist may devote to using the tourist product on the trail;

the remaining elements indicated in the model.

On the basis of the collected and classified data, an attempt was made to examine the tourist and ecological attractiveness of the thematic trail as a whole, as well as of its elements.

For this purpose, we applied the assumptions of the point grading method, popular in assessing the tourist attractiveness of values and regions. The method consists in assigning points to particular basic fields in which specific features of the natural or cultural environment that influence its tourist attractiveness are analysed. Each feature is assigned a specific point value in accordance with a fixed scale; the value results from the feature quality or the intensity of its occurrence [

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84]. The sum of points in a given basic field awarded for particular features allows for a synthetic assessment of a given field from the point of view of its attractiveness: in this case, tourist attractiveness [

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92]. The culmination of the process of assigning points to an area unit is qualification; with the consideration of the valorisation objective, the separate grading classes are assigned synthetic ratings, i.e., opinions on the quality of the elements of the examined set belonging to the class, e.g., very useful, useful with limitations, not useful [

93].

When analysing the elements of the tourist attractiveness of the trail (a linear product), we assumed the nodal points constituting the trail rather than the basic fields as the starting point. The grading considered their specific characteristics relevant in terms of sustainable development and tourist attractiveness.

In order to obtain a comprehensive assessment of the trail attractiveness, indices calculated on the basis of previously classified features were proposed. Three such indices were suggested for the purposes of the paper:

Regionality index of the product with respect to the thematic trail (RI): the evaluated feature was the elements influencing the regional character of the product constituting the basis of the gastronomic trail;

Tourism index of the thematic trail (TI): the evaluated feature was the complexity of the tourist offer at each of the trail stops;

Stay attractiveness index (SAI): the evaluated feature was the time spent on getting to know the tourist product proposed in each site (length of stay at the site of value occurrence).

The values were calculated from the ratio of the total point value of a given trail feature to the maximum possible value multiplied by 100%. For each index, on the basis of source material analysis and types of tourist products offered on the trail, we proposed and calculated the value representing the limit from which the phenomenon described by the index could be referred to as occurring on the trail. The limit value equals 66% for the RI, 33% for the TI, and 50% for the SAI.

When classifying the tourist attractiveness (in the sustainable approach) of particular sites on the analysed trail, the assignment of points to specific trail stops involved three elements:

The regional character of the product constituting the attraction of the trail site;

The recognition of the product in the regional, national, and international scales, with the consideration of its certificates and their range;

The character of the tourist service.

The sum of points for the first two elements, referring to the product itself, was classified by grouping the sites on the trail into three possible classes from I to III, the same in size, starting from the minimum recorded value, up to the maximum one. Such classification is typical if the point grading method is applied [

89,

90,

92,

93,

94,

95]. Each class was assigned a point value from 1 to 3. The character of the tourist service was then grouped into five classes, each with an assigned value of 1–5 points. Then the points for belonging to the indicated classes were added up for each trail site; on this basis, the classes of the tourist attractiveness of all the trail elements were proposed. Five such classes were suggested:

Sites of low tourist attractiveness (class I);

Sites of average tourist attractiveness (class II);

Sites of tourist attractiveness (class III);

Sites of high tourist attractiveness (class IV);

Sites of extreme tourist attractiveness (class V).

In this way, the trail elements were determined that represent the highest tourist attractiveness with the consideration of the sustainable development idea.

3. Results and Discussion

The analysis of the particular elements influencing the sustainability of the thematic trail of the Land Flowing with Milk and Honey will indicate to what extent the studied trail is a tourist proposal of a sustainable character.

3.1. Product Regionality

Each trail site is characteristic because of a regional product. In accordance with the will of its creators, it should be associated with the leading theme of culinary products, mainly dairy products and honey. Considering the point grading method described above, we decided to assign points to specific features that affect quality, understood as product regionality. These features are the following: being characteristic of the region, the raw material from which the product is made, and the producer. If a product was characteristic of the region, made of local raw material, and manufactured by a local producer, 1 point was assigned for each of the features. The situation is different with regard to the last feature: product range. In this case, 1–3 points were assigned depending on the geographical range of the product. It was assumed that the more local the product, the more likely it was that a tourist would travel to get to know it. Therefore, 3 points were assigned for local/regional range, 2 points for national range, and 1 point for international range. In accordance with the subject literature (e.g., [

89,

93,

95]), in order to determine the regionality degree of the trail sites, the results for particular sites were grouped into the following classes: I (1–2 points), II (3–4 points), III (5–6 points) (

Table 2).

Each of the products constituting the trail should be regional in its character. For this purpose, it must fulfil at least three requirements:

it must be characteristic of the region in which it is made (a);

it should be manufactured from local raw material (b);

it must be made by a local producer (c).

For each of the above requirements, the product was assigned 1 point.

Another requirement is the product range (d). It is less significant, although one should emphasize that the smaller the range, the greater the tourist attractiveness, as the product availability outside the region increases. This may result in giving up the visit to the production region. Depending on the extent to which this requirement was met, the product might score 1–3 points.

Therefore, the minimum number of points that a product should obtain (for elements a–d) to be considered regional is 4, while the maximum equals 6. The regional character of the trail is then ensured if the sum of points obtained by all products on the trail is at least 66% of the maximum number of points possible to gain (4/6 × 100% = 66%).

In this context, the trail coefficient should be greater than 66% to allow to state that a thematic tourist trail has a regional character, which in the case of a product determines its value and uniqueness.

where RI is the regionality index, Ʃ

n is the number of points obtained in the assessment of the regional character of the products, and n(max) is the maximum number of points that the tourist trail can obtain in this category.

The result indicates a high regionality of the product constituting the basis of the trail of the Land Flowing with Milk and Honey. This is significant in terms of sustainability, which emphasizes product regionality and locality in the context of the raw material, manufacturing techniques, and the producer. These elements are important factors increasing tourist attractiveness.

3.2. Quality Certificate

Another important element confirming quality in terms of sustainability is the relevant certificates awarded to the products which constitute the basis of the trail. What is important in this case is both the number of the certificates and their weight. We awarded 3 points for a certificate whose obtaining was linked to the fulfilment of specific conditions regulated by law, and 1 point for any other certificate, including those of a tourist nature. Owing to the different number of certificates, we decided to assign 1 point for one certificate, 2 points for up to three certificates, and 3 points for more than three certificates held within a specific trail site. Also, the certificate range was translated into points: 1 point for the local or regional range, 2 points for the national range, and 3 points for the international range. In order to determine the product quality, the results for particular sites were grouped into the following classes: I (1–7 points), II (8–14 points), III (≥15 points) (

Table 3).

As mentioned above, we classified the regional quality of a product, resulting from its regional character and the quality expressed by relevant certificates, as well as its value in creating a tourist service. The final effect is the obtained scale of tourist and sustainable attractiveness of particular trail sites.

3.3. Tourist Attractiveness of the Trail Sites

The tourist and sustainable attractiveness of the sites constituting the trail (

Table 4) was established on the basis of the total number of points assigned for product regionality in a given site (

Table 2) and its range expressed in the number and weight of certificates held (

Table 3). The values were grouped into classes I–V (class I: 1 point, class V: 5 points). Class I involved products that obtained 1–5 points for regional quality, class II: those with 6–10 points, class III: those with 11–15 points, class IV: those with 16–20 points, and class V: those with >20 points. Then, tourist services were classified as analysed in the context of the tourist availability of the trail (

Table 5). Classes I–V were identified (class I: 1 point, class V: 5 points). Class I involved trail sites that obtained 1 point in the classification, class II: those with 2 points, class III: those with 3 points, class IV: those with 4 points, class V: those with ≥5 points. Summing up the points for the relevant classes, we achieved a scale of tourist and sustainable attractiveness of the trail sites. Sites that obtained the total of 1–2 points were classified as those of low attractiveness (+), sites with 3–4 points as those of average attractiveness (++), sites with 5–6 points as attractive (+++), sites with 7–8 points as those of high attractiveness (++++), and sites with 9–10 points as those of extreme attractiveness (+++++).

It is worth noticing that among 22 trail sites, only one represents low attractiveness. The result confirms the first impression. It is a hive production plant, an important element in the production of honey, but less attractive in terms of the culinary character of the trail. Although it has the potential expressed by an appropriate certificate, it is not used in any way to create an attractive product for potential tourists. Tourists are welcome here, but they visit this place rather occasionally. Also, only one site is of extreme attractiveness. It is the Bożena and Daniel Sokołowskis’ ‘Goat Meadow’ (Kozia Łąka) ecological farm in Łomnica. The offered tourist product is of complex character, and the product on which it was based is recognized as regional and of high quality, confirmed by appropriate certificates. Another four sites from among 22 have the range of high tourist attractiveness, and five are classified as attractive. A total of 10 (45%) trail sites are attractive or very attractive.

3.4. Tourist Availability of the Trail

Another analysed element is the tourist availability of the thematic trail, in this case translating into the complexity of the tourist service offered in a particular trail site (

Table 5). Seven levels of service complexity were distinguished. Each was assigned a specific point value, with the assumption that the more complex the service, the higher the point value. The levels were the following:

a simple service, i.e., the sale of a product at the manufacturing site: 1 point (class I);

sale of a product + catering service: 2 points (class II);

sale of a product + interpretation: 3 points (class III);

sale of a product + interpretation + catering service: 4 points (class IV);

sale of a product + accommodation service: 4 points (class IV);

sale of a product + interpretation + accommodation service: 5 points (class V);

sale of a product + interpretation + catering service + accommodation service: 6 points (class V).

One can try to evaluate the attractiveness of a trail as a real tourist product. In order for a thematic trail to be considered a trail of a tourist character, it should offer more than just a simple sale of the product which constituted the basis for its creation. Therefore, it can be assumed that the minimum that a trail should offer is the sale of a culinary product combined with the possibility of consuming it in the context of the catering service provided. As a consequence, the minimum value that the tourism index of the thematic trail should achieve is the sum of points obtained for the ‘sale of a product + catering service’ offer in each of the trail sites. Therefore, the minimum number of points to be achieved is 2, while the maximum equals 6. The tourist character of the trail is ensured if the sum of points obtained for the offer is at least 33% of the maximum number of points possible to gain (2/6 × 100% = 33%). A tourist character of a thematic trail can be identified with TI ≥33%.

where TI is the tourism index, Ʃ

n is the number of points obtained in the assessment of the tourist character of the trail, and n(max) is the maximum number of points that the tourist trail can obtain in this category.

Although the index has a relatively low value, it exceeds 33%. It can be thus stated that the thematic Land Flowing with Milk and Honey trail is a trail of a tourist nature.

3.5. Stay Attractiveness of the Trail

The element investigated above is bound with the issue of stay attractiveness in particular trail sites. The sites that practically offer merely the sale of a product have low stay attractiveness. They can only be considered as a stopover on the trail, a pretext for rest, provided that the given section of the route is sufficiently long. If they occur too often, the probability that they will be omitted increases. Therefore, the following point ranks were proposed for this element (

Table 6):

a short stay, up to 1 hour, associated with the time spent for purchasing the product: 1 point;

a longer stay, which could involve a potential tourist for a few hours: 2 points;

a full-day stay: 3 points;

an overnight stay: 4 points.

The points awarded will constitute the basis for determining the stay attractiveness index of the tourist trail. The stay attractiveness depends on the time that can be spent using the offer at each trail stop. It can be assumed that the stay attractiveness occurs if the trail sites offer some value added to the basic product. Here, one should consider the sites whose offer impacts on prolonging the stay by a significantly longer period than the time devoted to the purchase of the product. Thus, a trail should be considered as a trail of high stay attractiveness if its SAI equals at least 50%, i.e., statistically a tourist is engaged for up to several hours at each trail site. In this paper, this is referred to as a longer stay.

Therefore, the minimum number of points to be achieved is 2, while the maximum equals 6. The stay attractiveness of the trail is ensured if the sum of points obtained is at least 50% of the maximum number of points possible to gain (2/4 × 100% = 50%).

In view of the above, the stay attractiveness index of the Land Flowing with Milk and Honey equals 36 points for the 88 consisting the maximum value for the whole trail.

where SAI is the stay attractiveness index, Ʃ

n is the number of points obtained in the assessment of the stay attractiveness of the trail, and n(max) is the maximum number of points that the tourist trail can obtain in this category.

The index value for the analysed trail is lower than 50%, which implies that this is not a trail of high stay attractiveness. This is mainly due to the inclusion of too many entities which, although attractive from the sustainability point of view, offer only the sale of a product. It refers to as many as 12 of the 22 sites that constitute the trail, with two not classified at all. Among the eight sites that keep tourists for a longer time, three (13.6% of all sites) offer a complex stay with accommodation, catering, and complementary service.

3.6. The Remaining Trail Elements

Finally, it is worth exploring the remaining elements that strengthen the tourist character of the analysed thematic trail in the context of sustainable development. Four features were considered, described in

Table 7.

In the complex analysis of the presence of the remaining elements that indicate the tourist and sustainable character of thematic trails, we took four factors into account: (1) availability of the tourist goods on which the trail was based; (2) participation in the trail organization of local authorities or associations which aim at popularizing the value; (3) consideration of the trail character in its promotion, in this case translating into an emphasis on the ecological character of the value; and (4) site relationship with more than one thematic tourist trail, significantly strengthening its position among various tourist offers in the region. One can assume that if the total value of positive indications exceeds 50%, a tourist and sustainable character of a trail can be declared. In the case of the Land Flowing with Milk and Honey, 55 out of 88 possible indications were positive. Therefore, the percentage value of the index equals 62.5%. The situation is similar if only elements implying the tourist character are taken into account: availability and relationship with similar tourist products. Here, 29 out of 44 possible indications were positive, which results in the index value of 65.9%. The same occurs if the remaining two of the analysed elements, pointing at the sustainable character of a trail, are considered: 26 out of 44 possible indications were positive. The index equals 59%. It can therefore be stated that the investigated trail has a tourist character also with regard to these elements, and factors of sustainable development were considered in the trail organization.

A product—the value that constituted the basis for the thematic trail creation—is always the trail’s key element. Its choice should be well considered: the product has to represent the region on the one hand, and fulfil the assumptions of sustainable development in tourism on the other. Thus, the conditions that should be met by the proposed products allowing them to co-create a trail should be clearly defined. These are, first of all, uniqueness and quality, consistent with the idea of sustainable development. The next important stage is the appropriate preparation of a tourist product on the basis of the proposed value. It should take into account the tourist’s needs and not destroy the sustainable character of the trail, with the emphasis on an individual and not mass character of the offer. The elements proposed in the present paper that influence the sustainable character of the trail meet these requirements. The quality of a product results from the process of its creation, involving the material, the technique, and the creator. Likewise, uniqueness stems from the regional character of the process. However, it is equally important to appropriately adapt the trail to the needs of tourism. Here, the ideas of sustainable development should be considered, expressed on a suitable scale. There is no place for mass tourism. Finding a balance between the tourist market demands and the sustainable usage of the proposed value may be problematic. Accents must always be correctly distributed. The mere accumulation of many attractive products is not enough if they are not presented to tourists in a sufficiently attractive way. The analysed Lower Silesian thematic trail faces a similar problem. The attractiveness of the products on the trail, expressed in their regionality and confirmed by certificates, is high (with the regionality index exceeding 90%) or at least satisfactory. The potential, however, does not fully translate into the tourist attractiveness of all trail sites. The tourism index of the thematic trail remained within the permissible range but was close to the lower limit, and the stay attractiveness index did not reach the lower limit. Although almost half of the 22 trail sites are attractive at the least, with the consideration of sustainable development principles, this did not entirely successfully result in tourist attractiveness. Too many sites are not able to maintain and be of interest to the tourist for a long time. This becomes visible in the tourist attractiveness of the offer of Land Flowing with Milk and Honey. The product needs to be prepared in such a way that the potential customer has the opportunity to spend more time on the site. A properly arranged interpretation of the value is required. Suitable interpretation constitutes an advantage to both the tourist and the local community. This seems to be the most important task that the organizers and co-creators of the trail face at the moment.

4. Conclusions

The analysis of one of the first thematic trails of sustainable character allowed us to identify the elements that determine its sustainability. Once again, it turned out that the role of the local community is significant [

19,

38,

43], and organizational activities, as implied in the literature [

24,

26,

45], are of local character. It is important to maintain a specific balance between the sustainability of the trail and its tourist function, which is emphasized by Inskeep [

31], Frey and George [

36], or Middleton [

35]. The natural environment plays an important role in the development of the studied trail, which remains in line with what is already known from literature [

8,

9,

16,

46]. It turns out that the high quality of the elements constituting the trail and their use for tourism are equally significant from the point of view of tourism. Even unique products need a suitable setting to make the thematic trail attractive for tourists. Thus, both the tourist infrastructure accompanying the values and the appropriate interpretation are of considerable importance. The latter is a story about the value that would for a longer time attract the attention of tourists interested in getting to know the value and the whole region.

Also, the practical aspect of the research presented in this publication should be emphasized. It often occurs that the concept of a sustainable approach to many activities, including tourism, remains only a declaration, not followed by specific actions. This study, with the proposed methodology, is an attempt to determine the conditions which raise the chance for an objective statement whether a specific tourist product (in this case, the thematic tourist trail) implements the idea of sustainable development in practice. Here, one should consider a sustainable trail pattern established on the basis of literature and discussion among professionals. We indicated the specific features of the product constituting the basis for trail creation, the method of tourist function implementation, the approach to managing the trail and its elements, and, finally, the role of the organizer and coordinator. It is worth stressing the comprehensive approach used in the research: on the one hand, we assessed the quality of the product in the context of sustainable development; on the other, we determined how the tourist function of the sustainable thematic trail was implemented. In principle, the paper includes all the relevant elements that allow to indicate to what extent the sustainable development concept is present in a project and actually remains relevant for the tourist product organizer.