Animal Ethics and Eating Animals: Consumer Segmentation Based on Domain-Specific Values

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background: Animal-Ethical Intuitions

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Description of the Sample

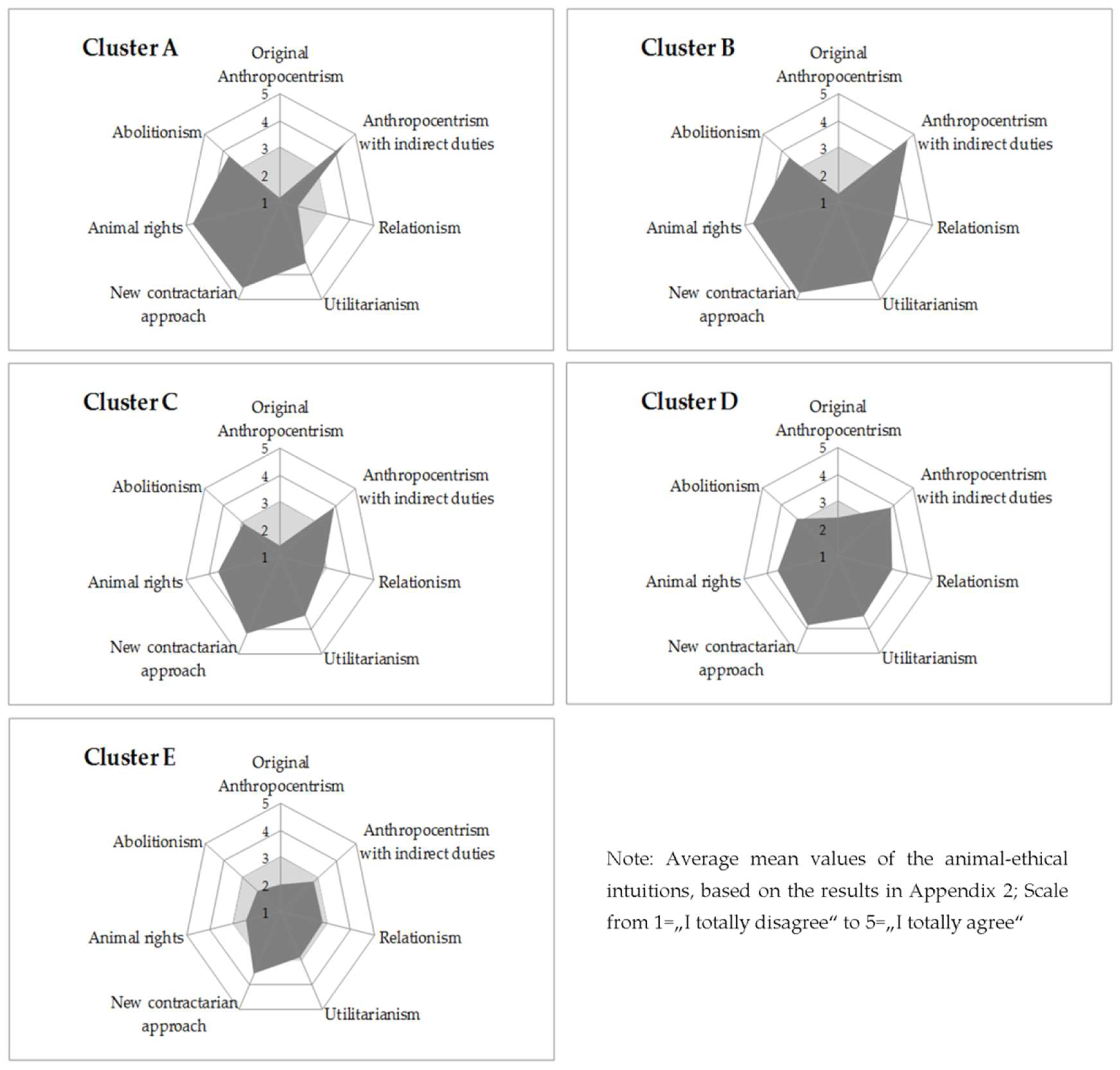

4.2. Cluster Analysis

4.3. Discriminant Analysis

4.4. Links between Consumer Segments and Diet

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sample | German Population [52] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | female | 51.0% | 50.9% |

| male | 49.0% | 49.1% | |

| Age | 18–24 years | 8.8% | 9.2% |

| 25–39 years | 20.4% | 22.1% | |

| 40–64 years | 44.6% | 43.7% | |

| 65 years and over | 26.3% | 25.1% | |

| Education | No graduation (yet) | 1.8% | 3.9% |

| Certificate of Secondary Education | 35.5% | 34.5% | |

| General Certificate of Secondary Education | 31.6% | 30.8% | |

| General qualification for university entrance | 14.1% | 13.8% | |

| University degree | 17.0% | 17.1% | |

| Net household income per month | <1300 € | 23.1% | 26.3% |

| 1300–2599 € | 41.8% | 39.6% | |

| 2600–4999 € | 30.2% | 27.1% | |

| >5000 € | 4.9% | 6.5% | |

| Diet | omnivore | 67.8% | - |

| flexitarian | 25.7% | 11.6% [28]/13.0% [29] | |

| vegetarian | 5.1% | 3.7% [28]/7.6% [30] | |

| vegan | 0.9% | 0.3% [28]/1.0% [31] |

Appendix B

| Cluster A (n = 248) | Cluster B (n = 236) | Cluster C (n = 271) | Cluster D (n = 88) | Cluster E (n = 59) | F-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original anthropocentrism (CA = 0.740; CR = 0.838; AVE = 0.569) | −0.5373a (±0.2544) | −0.3433b (±0.4534) | −0.1880c (±0.4245) | 1.9351d (±1.1342) | 1.0443e (±1.1864) | 367,011 |

| Anthropocentrism with indirect duties (CA = 0.755; CR = 0.859; AVE = 0.669) | 0.4690a (±0.7101) | 0.6435b (±0.5428) | −0.4068c (±0.7616) | −0.5159c (±0.6602) | −1.9124d (±0.9380) | 222,747 |

| Relationism (CA = 0.726; CR = 0.840; AVE = 0.638) | −1.0960a (±0.6689) | 0.6859b (±0.8219) | 0.1510c (±0.7203) | 0.6483b (±0.5818) | 0.0644c (±0.8679) | 210,203 |

| Utilitarianism (CA = 0.711; CR = 0.837; AVE = 0.631) | −0.1497a (±1.1169) | 0.7862b (±0.7862) | −0.2438a (±0.7219) | −0.1775a (±0.6117) | −0.9635c (±0.8413) | 75,558 |

| New contractarian approach (CA = 0.704; CR = 0.794; AVE = 0.503) | 0.4122a (±0.7614) | 0.6946b (±0.5061) | −0.2873c (±0.7688) | −0.8799d (±0.8694) | −1.4232e (±0.9172) | 171,499 |

| Animal rights (CA = 0.886; CR = 0.921; AVE = 0.744) | 0.7227a (±0.4777) | 0.6500a (±0.4996) | −0.5419b (±0.6540) | −0.6346b (±0.6923) | −1.9232c (±0.8942) | 395,696 |

| Abolitionism (CA = 0.752; CR = 0.843; AVE = 0.573) | 0.5490a (±0.8757) | 0.4179a (±0.9148) | −0.5022b (±0.6936) | −0.1924c (±0.6958) | −1.4374d (±0.6480) | 119,148 |

Appendix C

| Cluster A (n = 248) | Cluster B (n = 236) | Cluster C (n = 271) | Cluster D (n = 88) | Cluster E (n = 59) | Sample (n = 1046) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original anthropocentrism (CA = 0.740; CR = 0.838; AVE = 0.569) | 1.14 | 1.29 | 1.39 | 2.40 | 2.00 | 1.45 |

| Humans are allowed to do what they want with animals. G | 1.03a (±0.177) | 1.08ab (±0.354) | 1.16b (±0.404) | 2.48d (±1.039) | 1.90c (±0.759) | 1.30 (±0.690) |

| We are allowed to treat animals as we please, because they are just animals. G | 1.01a (±0.090) | 1.05a (±0.256) | 1.14b (±0.401) | 2.33c (±0.880) | 1.93c (±0.868) | 1.27 (±0.630) |

| We may cause pain to animals at any time, because they are just animals. G | 1.01a (±0.090) | 1.05a (±0.388) | 1.04a (±0.206) | 2.03c (±0.976) | 1.51b (±0.653) | 1.17 (±0.526) |

| Humans may use animals without any restrictions. G | 1.49a (±0.795) | 1.96b (±1.008) | 2.23c (±0.843) | 2.75d (±0.820) | 2.64d (±0.905) | 2.05 (±0.969) |

| Anthropocentrism with indirect duties (CA = 0.755; CR = 0.859; AVE = 0.669) | 4.56 | 4.69 | 3.89 | 3.83 | 2.78 | 3.31 |

| Only the one who is kind-hearted to animals is also kind-hearted to humans. G | 4.33a (±0.901) | 4.50a (±0.796) | 3.57b (±0.948) | 3.60b (±0.720) | 2.37c (±1.049) | 3.98 (± 1.036) |

| We must not be cruel to animals; otherwise we may also be cruel to humans later on. G | 4.62a (±0.727) | 4.75a (±0.601) | 3.97b (±0.858) | 3.92b (±0.746) | 2.81c (±1.137) | 4.27 (± 0.921) |

| We should treat animals well, in order not to become brutal ourselves. G | 4.74a (±0.583) | 4.83a (±0.473) | 4.17b (±0.625) | 3.98b (±0.625) | 3.15c (±0.827) | 4.41 (± 0.752) |

| Relationism (CA = 0.726; CR = 0.840; AVE = 0.638) | 1.78 | 3.37 | 2.89 | 3.33 | 2.81 | 2.75 |

| We are more committed to our pets than we are to farm animals. G | 1.56a (±0.706) | 3.19bc (±1.131) | 2.75d (±0.880) | 3.32c (±0.781) | 2.78b (±1.052) | 2.59 (±1.125) |

| We have more far-reaching obligations towards domesticated animals than towards wild animals. G | 2.11a (±1.081) | 3.56b (±0.955) | 3.15c (±0.858) | 3.42b (±0.754) | 2.97c (±0.928) | 3.00 (±1.095) |

| Pets should be given increased protection compared to farm animals.G | 1.66a (±0.829) | 3.36b (±1.164) | 2.77c (±0.868) | 3.25b (±0.834) | 2.68c (±0.918) | 2.67 (±1.157) |

| Utilitarianism (CA = 0.711; CR = 0.837; AVE = 0.631) | 3.52 | 4.24 | 3.44 | 3.49 | 2.88 | 3.64 |

| Humans should weigh off the interests of animals against their own as well. G | 3.38a (±1.138) | 4.07b (±0.922) | 3.28a (±0.753) | 3.38a (±0.700) | 2.69c (±0.815) | 3.48 (±0.992) |

| If we use animals for our purposes, we must weigh off the consequences for humans and animals against each other. G | 3.75a (±1.091) | 4.41b (±0.801) | 3.60a (±0.748) | 3.56a (±0.738) | 3.15c (±0.847) | 3.82 (±0.943) |

| The interests of humans and animals should be weighed off against each other. G | 3.42a (±1.054) | 4.24b (±0.893) | 3.45a (±0.723) | 3.53a (±0.710) | 2.81c (±0.991) | 3.62 (±0.971) |

| Cluster A (n = 248) | Cluster B (n = 236) | Cluster C (n = 271) | Cluster D (n = 88) | Cluster E (n = 59) | Sample (n = 1046) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New contractarian approach (CA = 0.704; CR = 0.794; AVE = 0.503) | 4.44 | 4.74 | 4.18 | 3.86 | 3.55 | 4.35 |

| If we use animals, we should ensure a good life for them. G | 4.90a (±0.315) | 4.95a (±0.231) | 4.42b (±0.544) | 4.03c (±0.615) | 3.81c (±0.629) | 4.60 (±0.586) |

| When using animals, people are committed to take best possible care of them. G | 4.89a (±0.376) | 4.92a (±0.359) | 4.31b (±0.689) | 3.99d (±0.669) | 3.59c (±0.873) | 4.54 (±0.700) |

| We may only use animals for our own purposes if we treat them well. G | 4.16a (±1.162) | 4.47b (±0.929) | 3.89c (±0.789) | 3.66cd (±0.843) | 3.27d (±0.944) | 4.06 (±1.015) |

| We may use animals for our purposes, but we should do our best to meet their needs. G | 4.22a (±1.081) | 4.60b (±0.779) | 4.10a (±0.718) | 3.76c (±0.830) | 3.51c (±0.858) | 4.18 (±0.914) |

| Animal rights (CA = 0.886; CR = 0.921; AVE = 0.744) | 4.70 | 4.64 | 3.62 | 3.55 | 2.46 | 4.09 |

| Animals, as well as humans, should have certain fundamental rights. G | 4.68a (±0.569) | 4.54a (±0.654) | 3.49b (±0.779) | 3.41b (±0.866) | 2.17c (±0.931) | 3.98 (±1.024) |

| We should also grant animals something similar to human rights. G | 4.56a (± 0.665) | 4.48a (±0.711) | 3.39b (±0.836) | 3.38b (±0.807) | 2.12c (±0.892) | 3.91 (±1.044) |

| Animals should also have the fundamental right to be treated with dignity. G | 4.85a (±0.390) | 4.86a (±0.355) | 3.94b (±0.710) | 3.82b (±0.751) | 2.90c (±1.078) | 4.34 (±0.861) |

| The right to physical integrity should also be granted to animals. G | 4.70a (±0.650) | 4.66a (±0.630) | 3.67b (±0.835) | 3.59b (±0.768) | 2.64c (±1.110) | 4.12 (±0.989) |

| Abolitionism (CA = 0.752; CR = 0.843; AVE = 0.573) | 3.72 | 3.62 | 2.93 | 3.17 | 2.22 | 3.32 |

| We must not deprive animals of their freedom. S | 4.27a (±0.803) | 4.17a (±0.854) | 3.41b (±0.802) | 3.44b (±0.756) | 2.58c (±0.914) | 3.81 (±0.961) |

| It is wrong to use animals for our purposes. G | 3.34a (±1.112) | 3.11ab (±1.117) | 2.60c (±0.810) | 2.89bc (±0.903) | 1.68d (±0.860) | 2.91 (±1.092) |

| Animals have a right to freedom. S | 4.51a (±0.779) | 4.46a (±0.740) | 3.55b (±0.748) | 3.76b (±0.802) | 3.03c (±0.870) | 4.04 (±0.927) |

| We must not, under any circumstances, use animals for our purposes. G | 2.74a (±1.075) | 2.72a (±1.114) | 2.15b (±0.868) | 2.60a (±0.878) | 1.59c (±0.812) | 2.50 (±1.059) |

Appendix D

| Predicted Cluster Allocation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | Total | ||

| Original Cluster Allocation | A | 98.0% | 0.8% | 1.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| B | 2.5% | 96.2% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | |

| C | 1.5% | 2.2% | 95.2% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 100.0% | |

| D | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4.5% | 93.2% | 2.3% | 100.0% | |

| E | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.4% | 5.1% | 91.5% | 100.0% | |

Appendix E

| Functions | Eigenvalue | Explained Variance | Canonical Correlation | Wilks’ λ | χ2 | df | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.342 | 69.4% | 0.902 | 0.049 | 2692.309 | 28 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 1.192 | 19.1% | 0.737 | 0.264 | 1192.653 | 18 | 0.000 |

| 3 | 0.710 | 11.3% | 0.644 | 0.578 | 490.217 | 10 | 0.000 |

| 4 | 0.012 | 0.2% | 0.107 | 0.989 | 10.235 | 4 | 0.037 |

Appendix F

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Average * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original anthropocentrism | −0.431 | 0.274 | 0.838 | 0.079 | 0.4463 |

| Anthropocentrism with indirect duties | 0.356 | 0.109 | 0.192 | −0.803 | 0.2912 |

| Relationism | −0.117 | 0.836 | −0.440 | −0.126 | 0.2908 |

| Utilitarianism | 0.181 | 0.484 | −0.074 | 0.355 | 0.2271 |

| New contractarian approach | 0.429 | 0.074 | 0.029 | 0.493 | 0.3161 |

| Animal rights | 0.482 | 0.153 | 0.272 | 0.090 | 0.3946 |

| Abolitionism | 0.292 | −0.013 | 0.292 | 0.198 | 0.2385 |

References

- Busch, G.; Gauly, M.; Spiller, A. Opinion paper: What needs to be changed for successful future livestock farming in Europe? Animal 2018, 12, 1999–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Aveyard, P.; Garnett, T.; Hall, J.W.; Key, T.J.; Lorimer, J.; Pierrehumbert, R.T.; Scarborough, P.; Springmann, M.; Jebb, S.A. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science 2018, 361, eaam5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aleksandrowicz, L.; Green, R.; Joy, E.J.M.; Smith, P.; Haines, A. The Impacts of Dietary Change on Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Land Use, Water Use, and Health: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clune, S.; Crossin, E.; Verghese, K. Systematic review of greenhouse gas emissions for different fresh food categories. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 766–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruby, M.B. Vegetarianism. A blossoming field of study. Appetite 2012, 58, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, M.; Busch, C.; Rödiger, M.; Hamm, U. Motives of consumers following a vegan diet and their attitudes towards animal agriculture. Appetite 2016, 105, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beardsworth, A.D.; Keil, E.T. Vegetarianism, Veganism, and Meat Avoidance. Recent Trends and Findings. Br. Food J. 1991, 93, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. Attitude structure and function. In The handbook of Social Psychology: Volume 1, 4th ed.; Gilbert, D.T., Fiske, S.T., Lindzey, G., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 269–322. [Google Scholar]

- Vinson, D.E.; Scott, J.E.; Lamont, L.M. The Role of Personal Values in Marketing and Consumer Behavior. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, T.B.; McKeegan, D.E.F.; Cribbin, C.; Sandøe, P. Animal Ethics Profiling of Vegetarians, Vegans and Meat-Eaters. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frey, U.J.; Pirscher, F. Willingness to pay and moral stance: The case of farm animal welfare in Germany. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölker, S.; von Meyer-Höfer, M.; Spiller, A. Inclusion of Animal Ethics into the Consumer Value-Attitude System Using the Example of Game Meat Consumption. Food Ethics 2019, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.F. Lay Theories: Everyday Understanding of Problems in the Social Sciences, 1st ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, G.; Spiller, A. Pictures in public communications about livestock farming. Anim. Front. 2018, 8, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grimm, H.; Wild, M. Tierethik zur Einführung. [Animal Ethics for Introduction]; Junius-Verlag: Hamburg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bossert, L. Tierethik. Die verschiedenen Positionen und ihre Auswirkungen auf die Mensch-nichtmenschliches Tier-Beziehung: [Animal ethics. The different positions and their effects on the human-non-human animal relationship.]. In Nachhaltige Lebensstile. Welchen Beitrag kann ein bewusster Fleischkonsum zu mehr Naturschutz, Klimaschutz und Gesundheit leisten?: [Sustainable Lifestyles. What Can Conscious Meat Consumption Contribute to Nature Conservation, Climate Protection and Health?]; Voget-Kleschin, L., Bossert, L., Ott, K., Eds.; Metropolis-Verlag: Marburg, Germany, 2014; pp. 32–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, I. Immanuel Kant’s Metaphysik der Sitten. Herausgegeben und erläutert von J. H. von Kirchmann. [Immanuel Kant’s Metaphysics of Morals]; von Kirchmann, J.H., Ed.; Heimann: Berlin, Germany, 1870. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E. Tierrechte und die verschiedenen Werte nichtmenschlichen Lebens: [Animal rights and the different values of non-human life]. In Tierethik: Grundlagentexte: [Animal Ethics: Basic Texts], 1st ed.; Schmitz, F., Ed.; Suhrkamp: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 287–380. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, P. Practical Ethics, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, V.; Anthony, R.; Röcklinsberg, H. The Ethical Contract as a Tool in Organic Animal Husbandry. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2004, 17, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J. Paradigmenwechsel in der landwirtschaftlichen Nutztierhaltung—Von betrieblicher Leistungsfähigkeit zu einer tierwohlorientierten Haltung: [Paradigm shift in livestock farming—From operational efficiency to animal welfare oriented husbandry]. Rechtswissenschaft 2016, 7, 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, T. The Case for Animal Rights; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Francione, G.L.; Garner, R. The Animal Rights Debate: Abolition or Regulation? Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krumpal, I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 2025–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, D.M.; Fernandes, M.F. The social desirability response bias in ethics research. J. Bus. Ethics 1991, 10, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS3; Smart PLS GmbH: Boenningstedt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cordts, A.; Spiller, A.; Nitzko, S.; Grethe, H.; Duman, N. Imageprobleme beeinflussen den Konsum. Von unbekümmerten Fleischessern, Flexitariern und (Lebensabschnitts-)Vegetariern: [Image problems affect consumption. About reckless meat eaters, flexitarians and (life stage) vegetarians]. FleischWirtschaft 2013, 7, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Techniker Krankenkasse. Anteil der Flexitarier in Deutschland im Jahr 2016 nach Geschlecht: [Proportion of flexitarians in Germany in 2016 by gender]. In Iss Was, Deutschland?: [Eat What, Germany?]; Techniker Krankenkasse: Hamburg, Germany, 2017; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- IfD Allensbach. Anzahl der Personen in Deutschland, die Sich Selbst als Vegetarier Einordnen Oder als Leute, die Weitgehend auf Fleisch Verzichten, von 2014–2018 (in Millionen): [Number of People in Germany Who Classify Themselves as Vegetarians or as People Who Largely Avoid Meat, from 2014–2018 (in Millions).]. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/173636/umfrage/lebenseinstellung-anzahl-vegetarier/ (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- IfD Allensbach. Personen in Deutschland, die Sich Selbst als Veganer Einordnen Oder als Leute, die Weitgehend auf Tierische Produkte Verzichten, in den Jahren 2015 bis 2017: [Persons in Germany Who Classify Themselves as Vegans or as People Who Largely Avoid Animal Food Products, in the Years 2015 to 2017]. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/445155/umfrage/umfrage-in-deutschland-zu-anzahl-der-veganer/ (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Backhaus, K.; Erichson, B.; Plinke, W.; Weiber, R. Multivariate Analysemethoden. Eine Anwendungsorientierte Einführung. [Multivariate Analysis Methods. An Application-Oriented Introduction], 14th ed.; Springer Gabler: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cudeck, R. Factor Analysis in the Year 2004: Still Spry at 100. In Factor Analysis at 100. Historical Developments and Future Directions; Cudeck, R., MacCallum, R.C., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson, P.R.; Inglehart, R. Value Change in Global Perspective; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sandøe, P.; Palmer, C.; Corr, S.; Serpell, J.A. History of companion animals and the companion animal sector. In Companion Animal Ethics; Sandøe, P., Corr, S., Palmer, C., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2016; pp. 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, A.; Arzt, R.; Facklamm, A.; Mayer, D.; Grünewald, V. ZZF (Zentralverband Zoologischer Fachbetriebe Deutschlands e.V.) Jahresbericht 2017/2018. ZZF (Zentralverband Zoologischer Fachbetriebe Deutschlands e.V.) Annual Report 2017/2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.zzf.de/publikationen/jahresbericht.html (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Spencer, S.; Decuypere, E.; Aerts, S.; de Tavernier, J. History and Ethics of Keeping Pets: Comparison with Farm Animals. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratanova, B.; Loughnan, S.; Bastian, B. The effect of categorization as food on the perceived moral standing of animals. Appetite 2011, 57, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, S. Human attitudes towards animals in relation to species similarity to humans: A multivariate approach. Biosci. Horiz. 2009, 2, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, L.U.; Elwood, R.W.; Adamo, S.A.; Leach, M.C. Defining and assessing animal pain. Anim. Behav. 2014, 97, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paul, E.S.; Harding, E.J.; Mendl, M. Measuring emotional processes in animals: The utility of a cognitive approach. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 469–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wey, T.; Blumstein, D.T.; Shen, W.; Jordán, F. Social network analysis of animal behaviour: A promising tool for the study of sociality. Anim. Behav. 2008, 75, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, L. Thinking chickens: A review of cognition, emotion, and behavior in the domestic chicken. Anim. Cogn. 2017, 20, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. Fish intelligence, sentience and ethics. Anim. Cogn. 2015, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-G.; Sykes, M. Xenotransplantation: Current status and a perspective on the future. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare. Scientific Opinion on the influence of genetic parameters on the welfare and the resistance to stress of commercial broilers. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare. Scientific Opinion on the welfare of cattle kept for beef production and the welfare in intensive calf farming systems. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; Praet, I. Animal Killing and Postdomestic Meat Production. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2017, 30, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, J.; Ruby, M.B.; Loughnan, S.; Luong, M.; Kulik, J.; Watkins, H.M.; Seigerman, M. Rationalizing meat consumption. The 4Ns. Appetite 2015, 91, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meuwissen, M.P.M.; van der Lans, I.A.; Huirne, R.B.M. Consumer preferences for pork supply chain attributes. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2007, 54, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Risius, A.; Hamm, U. Exploring Influences of Different Communication Approaches on Consumer Target Groups for Ethically Produced Beef. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2018, 31, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Statistisches Jahrbuch 2016. Deutschland und Internationales. [Statistical Yearbook 2016. Germany and International Affairs]; Statistisches Bundesamt: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016.

| Negative | Indifferent | Positive | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original anthropocentrism (CA = 0.740; CR = 0.838; AVE = 0.569) | ||||

| Humans are allowed to do what they want with animals. | 92.9% | 4.5% | 2.0% | 1.30 (±0.690) |

| We are allowed to treat animals as we please, because they are just animals. | 93.0% | 4.2% | 1.5% | 1.27 (±0.630) |

| We may cause pain to animals at any time because they are just animals. | 95.8% | 2.3% | 1.1% | 1.17 (±0.526) |

| Humans may use animals without any restrictions. | 66.4% | 26.6% | 6.1% | 2.05 (±0.969) |

| Anthropocentrism with indirect duties (CA = 0.755; CR = 0.859; AVE = 0.669) | ||||

| Only the one who is kind-hearted to animals is also kind-hearted to humans. | 8.0% | 21.9% | 69.8% | 3.98 (±1.036) |

| We must not be cruel to animals; otherwise we may also be cruel to humans later on. | 5.1% | 11.0% | 83.4% | 4.27 (±0.921) |

| We should treat animals well, in order not to become brutal ourselves. | 2.0% | 7.9% | 88.9% | 4.41 (±0.752) |

| Relationism (CA = 0.726; CR = 0.840; AVE = 0.638) | ||||

| We are more committed to our pets than we are to farm animals. | 45.2% | 33.6% | 20.6% | 2.59 (±1.125) |

| We have more far-reaching obligations towards domesticated animals than towards wild animals. | 27.8% | 39.6% | 31.6% | 3.00 (±1.095) |

| Pets should be given increased protection compared to farm animals. | 43.1% | 33.7% | 22.7% | 2.67 (±1.157) |

| Utilitarianism (CA = 0.711; CR = 0.837; AVE = 0.631) | ||||

| Humans should weigh off the interests of animals against their own as well. | 12.2% | 40.0% | 46.7% | 3.48 (±0.992) |

| If we use animals for our purposes, we must weigh off the consequences for humans and animals against each other. | 6.1% | 29.2% | 64.1% | 3.82 (±0.943) |

| The interests of humans and animals should be weighed off against each other. | 8.1% | 39.9% | 51.3% | 3.62 (±0.971) |

| New contractarian approach (CA = 0.704; CR = 0.794; AVE = 0.503) | ||||

| If we use animals, we should ensure a good life for them. | 0.2% | 4.5% | 94.0% | 4.60 (±0.586) |

| When using animals, people are committed to take best possible care of them. | 1.5% | 5.9% | 92.1% | 4.54 (±0.700) |

| We may only use animals for our own purposes if we treat them well. | 7.1% | 17.8% | 74.1% | 4.06 (± 1.015) |

| We may use animals for our purposes, but we should do our best to meet their needs. | 4.7% | 15.4% | 79.6% | 4.18 (±0.914) |

| Animal rights (CA = 0.886; CR = 0.921; AVE = 0.744) | ||||

| Animals, as well as humans, should have certain fundamental rights. | 8.6% | 20.2% | 70.1% | 3.98 (±1.024) |

| We should also grant animals something similar to human rights. | 9.9% | 21.8% | 67.7% | 3.91 (±1.044) |

| Animals should also have the fundamental right to be treated with dignity. | 3.8% | 10.3% | 84.6% | 4.34 (±0.861) |

| The right to physical integrity should also be granted to animals. | 5.7% | 19.7% | 73.9% | 4.12 (±0.989) |

| Abolitionism (CA = 0.752; CR = 0.843; AVE = 0.573) | ||||

| We must not deprive animals of their freedom. | 6.8% | 32.2% | 59.9% | 3.81 (±0.961) |

| It is wrong to use animals for our purposes. | 32.5% | 44.4% | 22.8% | 2.91 (±1.092) |

| Animals have a right to freedom. | 3.7% | 26.1% | 69.6% | 4.04 (±0.927) |

| We must not, under any circumstances, use animals for our purposes. | 48.6% | 38.7% | 12.3% | 2.50 (±1.059) |

| Variables | Wilks’ λ | F | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original anthropocentrism | 0.379 | 367.011 | 0.000 |

| Anthropocentrism with indirect duties | 0.502 | 222.747 | 0.000 |

| Relationism | 0.516 | 210.203 | 0.000 |

| Utilitarianism | 0.748 | 75.558 | 0.000 |

| New contractarian approach | 0.567 | 171.499 | 0.000 |

| Animal rights | 0.362 | 395.696 | 0.000 |

| Abolitionism | 0.653 | 119.148 | 0.000 |

| Variables | Cluster A | Cluster B | Cluster C | Cluster D | Cluster E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original anthropocentrism | −0.106 | −1.060 | −0.727 | 5.397 | 2.594 |

| Anthropocentrism with indirect duties | 0.828 | 0.898 | −0.667 | −0.713 | −3.108 |

| Relationism | −2.109 | 1.490 | 0.386 | 0.749 | −0.028 |

| Utilitarianism | −0.388 | 1.199 | −0.316 | −0.127 | −1.356 |

| New contractarian approach | 0.980 | 1.205 | −0.665 | −1.569 | −2.747 |

| Animal rights | 1.414 | 1.635 | −1.230 | −1.204 | −4.306 |

| Abolitionism | 0.878 | 0.495 | −0.692 | −0.441 | −1.847 |

| (Constant) | −4.239 | −4.116 | −2.484 | −8.383 | −14.010 |

| Cluster A (n = 248) | Cluster B (n = 236) | Cluster C (n = 271) | Cluster D (n = 88) | Cluster E (n = 59) | Sample (n = 1046) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omnivore | 50.4%− | 73.3% | 74.8% | 65.1% | 96.6%+ | 67.8% |

| Flexitarian | 34.6%+ | 24.2% | 22.6% | 27.9% | 3.4%− | 25.7% |

| Vegetarian | 13.4%+ | 2.1%− | 1.9%− | 5.8% | 0.0% | 5.1% |

| Vegan | 1.6% | 0.4% | 0.7% | 1.2% | 0.0% | 0.9% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hölker, S.; von Meyer-Höfer, M.; Spiller, A. Animal Ethics and Eating Animals: Consumer Segmentation Based on Domain-Specific Values. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143907

Hölker S, von Meyer-Höfer M, Spiller A. Animal Ethics and Eating Animals: Consumer Segmentation Based on Domain-Specific Values. Sustainability. 2019; 11(14):3907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143907

Chicago/Turabian StyleHölker, Sarah, Marie von Meyer-Höfer, and Achim Spiller. 2019. "Animal Ethics and Eating Animals: Consumer Segmentation Based on Domain-Specific Values" Sustainability 11, no. 14: 3907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143907

APA StyleHölker, S., von Meyer-Höfer, M., & Spiller, A. (2019). Animal Ethics and Eating Animals: Consumer Segmentation Based on Domain-Specific Values. Sustainability, 11(14), 3907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143907