e-Commerce Sustainability: The Case of Pinduoduo in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

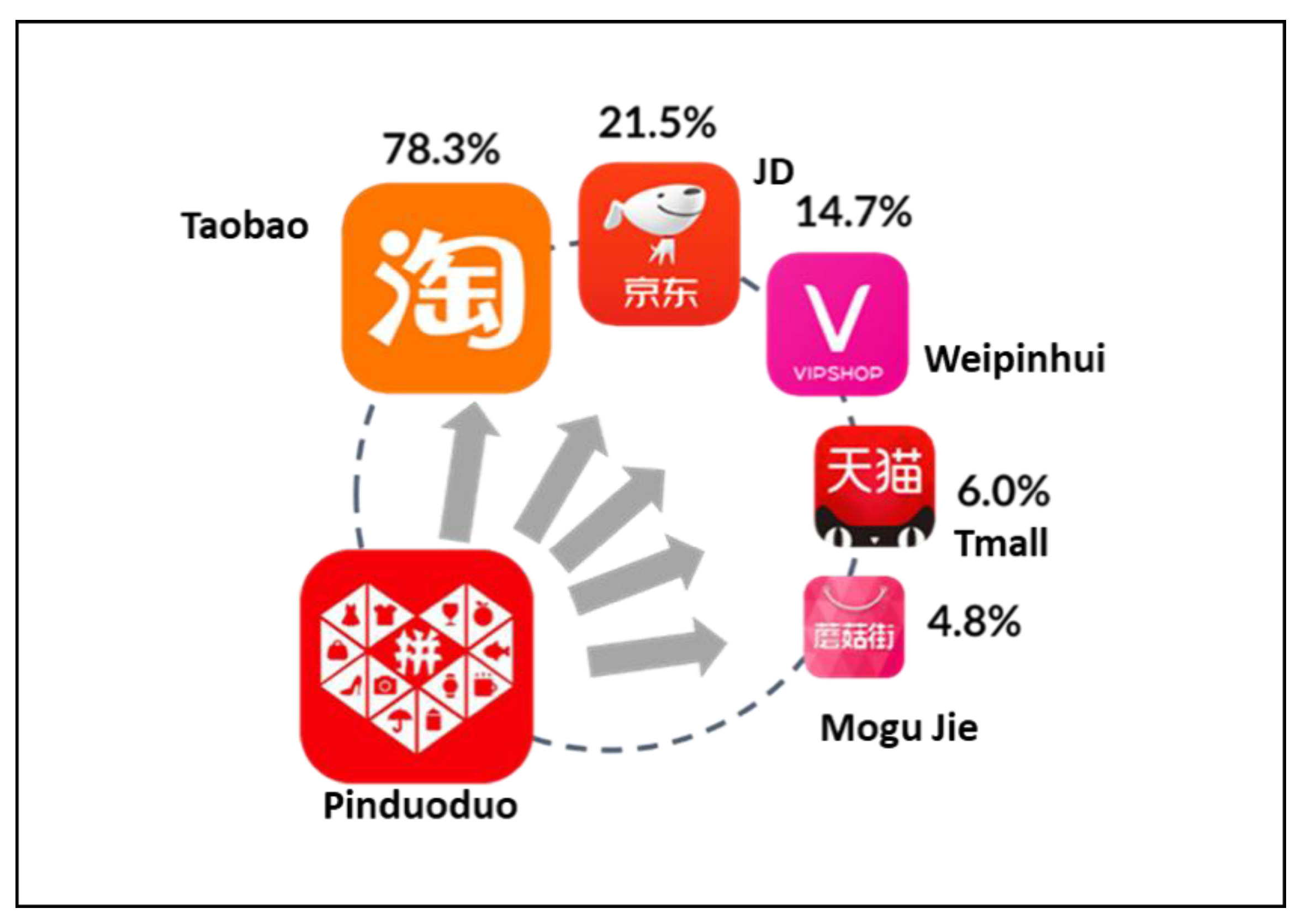

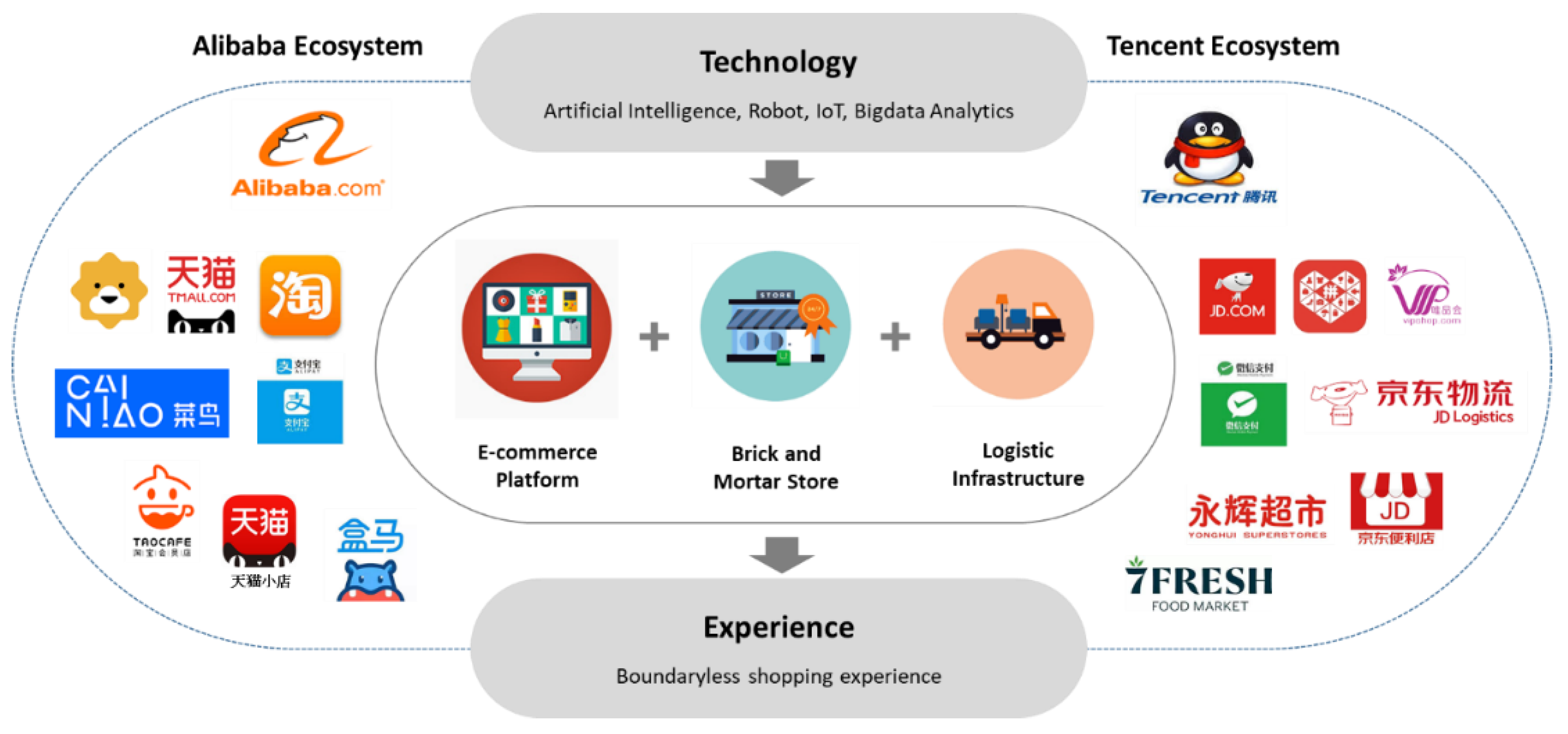

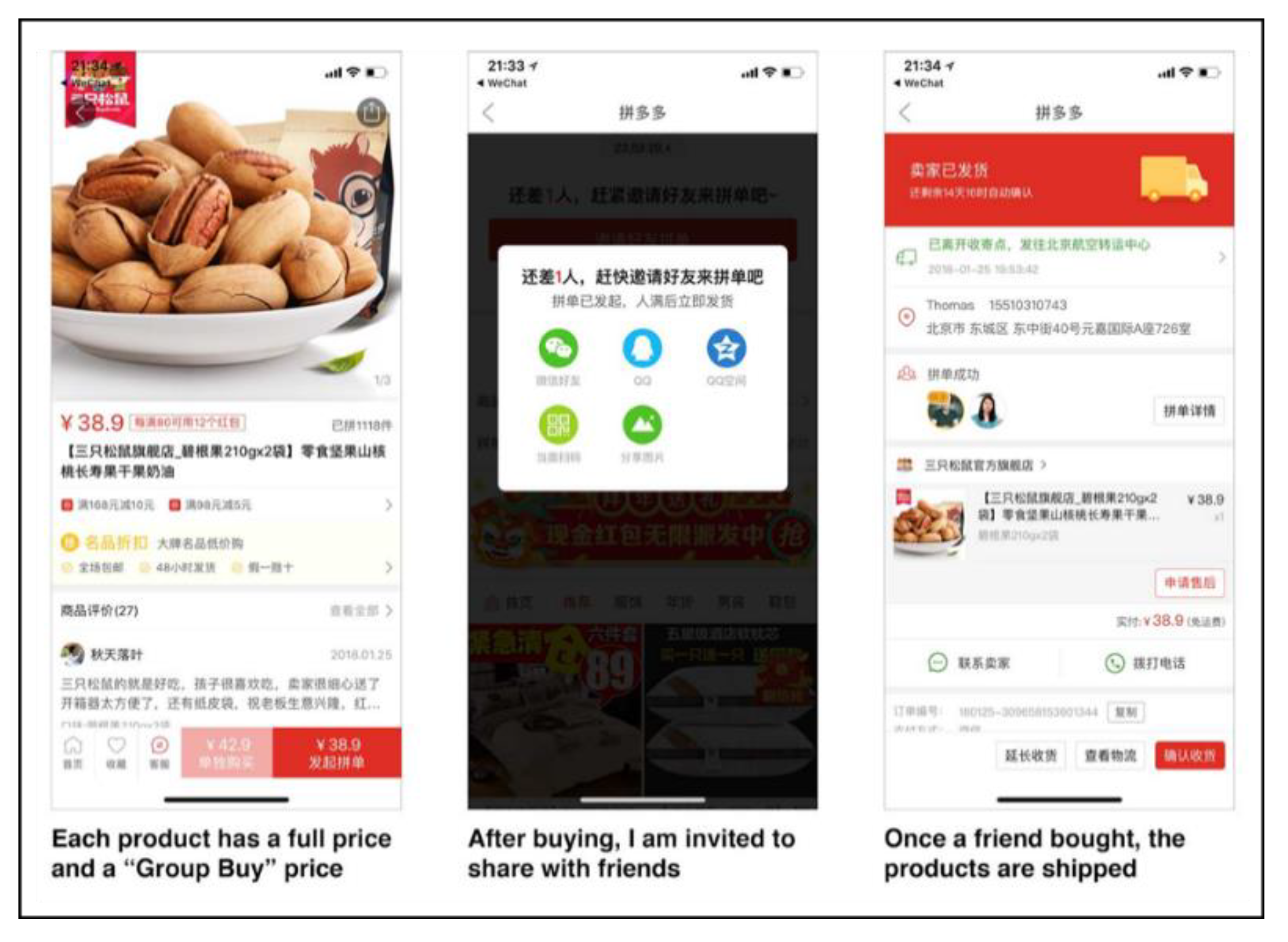

2.1. China e-Commerce Market and Pinduoduo

2.2. Customer Resistance to Change And Status Quo Bias Theory

2.3. Facets of Perceived Risk

2.4. Word of Mouth (WOM)

2.5. Preliminary Research: In-Depth Interview

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Perceived Product Quality

3.2. Trust

3.3. Switching Cost

3.4. Relative Attractiveness

3.5. Antecedents of Negative Attitude: Psychology Risk, Social Risk, Privacy Risk

3.6. Attitude, CRC, and WOM

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Procedure

4.2. Measurement Development

4.3. Research Sample

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Reliability and Validity of Our Measurement Model

5.2. Hypothesis Testing Results

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Discussion of Findings

6.2. Contributions

6.3. Limitation and Further Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russell, J. Alibaba Smashes its Single’s Day Record Once Again as Sales Cross $25 Billion. Available online: https://techcrunch.com/2017/11/11/alibaba-smashes-its-singles-day-record/ (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- JD.com. JD.com 6.18 Anniversary Sale Transaction Volume Reaches Record $24.7 Billion. Available online: https://jdcorporateblog.com/jd-com-6-18-anniversary-sale-transaction-volume-reaches-record-24-7-billion/ (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Tmall, J.D. CIW China Online Retail Exceeded US$593 bn in H1 2018. Available online: https://www.chinainternetwatch.com/26853/online-retail-h1-2018/ (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Shen, X. Pinduoduo Under Fire for Hosting Counterfeit Goods. Available online: https://www.abacusnews.com/big-guns/pinduoduo-under-fire-hosting-counterfeit-goods/article/2157617 (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Graziani, T. Pinduoduo: A Close Look at the Fastest Growing App in China. Available online: https://www.techinasia.com/talk/pinduoduo-fastest-growing-app-china (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Kim, S.Y.; Chang, Y.; Wong, S.F.; Park, M.C. Customer Resistance to Churn in a Mature Mobile Telecommunications Market. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.W.; Gupta, S. Investigating Customer Resistance to Change in Transaction Relationship with an I nternet Vendor. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Park, M.C.; Jeong, D.H. The effects of customer satisfaction and switching barrier on customer loyalty in Korean mobile telecommunication services. Telecommun. Policy 2004, 28, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Chan, H.C.; Lee, S.H. User resistance to software migration: The case on Linux. J. Database Manag. 2014, 25, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Kankanhalli, A. Investigating user resistance to information systems implementation: A status quo bias perspective. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherman, M.S.; Pavlou, P.A. Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk facets perspective. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2003, 59, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liangyu China Ecommerce Market to Grow 19% in 2017. Available online: http://english.gov.cn/news/top_news/2017/06/23/content_281475695038849.htm (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Reuters China to Probe Ecommerce Firm Pinduoduo Over Reports of Fake Goods. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-pinduoduo/china-to-probe-e-commerce-firm-pinduoduo-over-reports-of-fake-goods-idUSKBN1KM3FQ (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Zhao, R. Pinduoduo in Disputes with Store Owners After Quality Crackdown. Available online: https://technode.com/2018/06/15/pinduoduo-dispute-store-owners/ (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Oreg, S. Resistance to change: Developing an individual differences measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, R. Relationship Drivers of Customer Commitment. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2007, 15, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, W.; Zeckhauser, R. Status quo bias in decision making. J. Risk Uncertain. 1988, 1, 7–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C. Factors influencing the adoption of internet banking: An integration of TAM and TPB with perceived risk and perceived benefit. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2009, 8, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, U.; Kiran, R.; Sah, A.N. The influence of website functionality, drivers and perceived risk on customer satisfaction in online shopping: An emerging economy case. Inf. Syst. E Bus. Manag. 2018, 16, 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.B.; Kim, T.; Cha, H.S. The mediating role of perceived risk in the relationships between enduring product involvement and trust expectation. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 23, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, B. Understanding perceived risks in mobile payment acceptance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2015, 115, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, J.P.; Ryan, M.J. An investigation of perceived risk at the brand level. J. Mark. Res. 1976, 13, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, M.S. The Major Dimensions of Perceived Risk; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzarin, B.P.; Dimitrov, S. Mobile commerce and device specific perceived risk. Electron. Commer. Res. 2016, 16, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W. Customer satisfaction and word of mouth. J. Serv. Res. 1998, 1, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Jahan, N.; Fang, Y.; Hoque, S. Nexus of Electronic Word-Of-Mouth to Social Networking Sites: A Sustainable Chatter of New Digital Social Media. Sustainability 2019, 11, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Moon, H.S.; Kim, J.K. Analyzing the Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth on Low Involvement Products. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2017, 27, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.C.; Chih, W.H.; Liou, D.K. Investigating community members’ eWOM effects in Facebook fan page. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 978–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Park, J.H.; Jun, J.W. Brand Webtoon as Sustainable Advertising in Korean Consumers: A Focus on Hierarchical Relationships. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.T.; Kim, W.G.; Kim, H.B. The effects of perceived justice on recovery satisfaction, trust, word-of-mouth, and revisit intention in upscale hotels. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Chang, Y.; Wong, S.F.; Park, M.C. Customer attribution of service failure and its impact in social commerce environment. Int. J. Electron. Cust. Relatsh. Manag. 2014, 8, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzer, I.M.; Zeelenberg, M.; Pieters, R. “Never eat in that restaurant, I did!”: Exploring why people engage in negative word-of-mouth communication. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L. Negative word-of-mouth by dissatisfied consumers: A pilot study. J. Mark. 1983, 47, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeelenberg, M.; Pieters, R. Beyond valence in customer dissatisfaction: A review and new findings on behavioral responses to regret and disappointment in failed services. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A. The role of store image, perceived quality, trust and perceived value in predicting consumers’ purchase intentions towards organic private label food. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagin, A.J.; Metzger, M.J.; Pure, R.; Markov, A.; Hartsell, E. Mitigating risk in ecommerce transactions: Perceptions of information credibility and the role of user-generated ratings in product quality and purchase intention. Electron. Commer. Res. 2014, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoj, B.; Pisnik Korda, A.; Mumel, D. The relationships among perceived quality, perceived risk and perceived product value. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2004, 13, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, B.; Torrico, B.H.; Enkawa, T.; Schvaneveldt, S.J. Affect versus cognition in the chain from perceived quality to customer loyalty: The roles of product beliefs and experience. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Kang, S.; Moon, T. An empirical study on perceived value and continuous intention to use of smart phone, and the moderating effect of personal innovativeness. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 23, 53–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Zaltman, G.; Deshpande, R. Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spekman, R.E. Strategic supplier selection: Understanding long-term buyer relationships. Bus. Horiz. 1988, 31, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tax, S.S.; Brown, S.W.; Chandrashekaran, M. Customer evaluations of service complaint experiences: Implications for relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, G.L.; Sultan, F.; Qualls, W.J. Placing trust at the center of your Internet strategy. Sloan Manag. Rev. 2000, 42, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Ruan, W.; Park, Y. Effects of Service Quality, Corporate Image, and Customer Trust on the Corporate Reputation of Airlines. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wong, S.F.; Libaque-Saenz, C.F.; Lee, H. The role of privacy policy on consumers’ perceived privacy. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lee, H. Exploring user acceptance of streaming media devices: An extended perspective of flow theory. Inf. Syst. E Bus. Manag. 2018, 16, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Marchewka, J.T.; Lu, J.; Yu, C.S. Beyond concern—A privacy-trust-behavioral intention model of electronic commerce. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Fygenson, M. Understanding and predicting electronic commerce adoption: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, T.A.; Frels, J.K.; Mahajan, V. Consumer switching costs: A typology, antecedents, and consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2003, 31, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Chang, Y.; Wong, S.F.; Park, M.C. The effect of perceived risks and switching barriers on the intention to use smartphones among non-adopters in Korea. Inf. Dev. 2015, 31, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Yun, S. How Will Changes toward Pro-Environmental Behavior Play in Customers’ Perceived Value of Environmental Concerns at Coffee Shops? Sustainability 2019, 11, 3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. The Diffusion of Innovation, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Lim, E.T.; Goh, J.M.; Yang, F.; Lee, M.K. Customer’s reaction to cross-channel integration in omnichannel retailing: The mediating roles of retailer uncertainty, identity attractiveness, and switching costs. Decis. Support Syst. 2018, 109, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, M.; Oh, J.; Lee, H. Understanding Travelers’ Behavior for Sustainable Smart Tourism: A Technology Readiness Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlejohn, S.W.; Foss, K.A. Theories of Human Communication; Waveland press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Attitudes towards objects as predictors of single and multiple behavioral criteria. Psychol. Rev. 1974, 81, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour; Prentice-hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Wangenheim, F.; Bayon, T. Satisfaction, loyalty and word of mouth within the customer base of a utility provider: Differences between stayers, switchers and referral switchers. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2004, 3, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lee, H. Understanding user behavior of virtual personal assistant devices. Inf. Syst. E Bus. Manag. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.D.; Valacich, J.S.; Hess, T.J. What signal are you sending? How website quality influences perceptions of product quality and purchase intentions. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, M.P.; Havitz, M.E.; Howard, D.R. Analyzing the commitment-loyalty link in service contexts. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.W.; Kim, J.; Libaque-Saenz, C.F.; Chang, Y.; Park, M.C. Use and gratifications of mobile SNSs: Facebook and KakaoTalk in Korea. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, A.H.; Ferry, D.L. Measuring and Assessing Organizations; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Sirdeshmukh, D. Agency and trust mechanisms in consumer satisfaction and loyalty judgments. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.S.C. Understanding the role of satisfaction in the formation of perceived switching value. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 59, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Definition |

|---|---|

| Performance risk | “The possibility of the product malfunctioning and not performing as it was designed and advertised and therefore failing to deliver the desired benefits.” |

| Social risk | “Potential loss of status in one’s social group as a result of adopting a product or service, looking foolish or untrendy.” |

| Psychological risk | “The risk that the selection or performance of the producer will have a negative effect on the consumer’s peace of mind or self-perception.” |

| Privacy risk | “Potential loss of control over personal information, such as when information about you is used without your knowledge or permission. The extreme case is where a consumer is spoofed, meaning a criminal uses their identity to perform fraudulent transactions.” |

| Financial risk | “The probability that a purchase results in loss of money, as well as the subsequent maintenance cost of the product.” |

| Time risk | “Consumers may lose time when making a bad purchasing decision by wasting time researching and making the purchase, learning how to use a product or service only to have to replace it if it does not perform to expectations.” |

| Physical risk | “The probability that a purchased product results in a threat to human life.” |

| Interviewee Information | Previous Pinduoduo Experience | Current e-Commerce Platform | Interview Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, 21, 1st tier city | Yes | JD, Tmall | I have ordered some stationaries from Pinduoduo, but they lasted only a few days. Quality of products is terrible. |

| Female, 35, 2nd tier city | Yes | Taobao, JD | Too many group buying requests from friends and relatives. Difficult to say no to others. Sometimes received entirely different product and fake product. |

| Female, 28, 1st tier city | Yes | JD | When I am using Pinduoduo, people think I am a cheap person. Also, I saw many fake products in Pinduoduo. I am not going to buy anything from a platform that sells counterfeit products. Also I got more spam calls after using Pinduoduo. |

| Female, 23, 3rd tier city | Yes | Taobao, Tmall, JD | I bought a Korean cosmetic from Pinduoduo. It was not a Korean brand but a fake brand. Also I got skin trouble after using that cosmetic. I purchased this cosmetic together with others and they all said that the cosmetics have problems. I am not going to buy anything together with those who have gave suggestion to purchase this cosmetic. |

| Male, 19, 4th tier city | Yes | JD, Taobao | I used Pinduoduo several times. However, generally speaking, it is full of fake brands and products. I was thinking that it is targeting customers who want to buy cheap products at a low price. I will tell other people to never buy things from them. |

| Male, 26, 3rd tier city | Yes | Taobao, Tmall | I don’t use the Wechat pay, and I want to accumulate Zhima credit. I am also using finance service from Ant financial. Pinduoduo doesn’t provide these kinds of financial services when we are buying the things. Also, don’t have many choices and full of fake products. |

| Female, 20, 1st tier city | Yes | Tmall, JD | My mother asks me to use Pinduoduo, but this shopping mall keeps on sending me Wechat messages. Also, many people ask me to buy things together. Pinduoduo’s products are not as good as JD or Tmall. |

| Male, 29, 2nd tier city | Yes | Taobao | They don’t have many choices and there are too many fake products. Cannot trust this company. Purchased some computer accessories before but they were not working. |

| Female, 24, 1st tier city | Installed but never used | JD, Tmall, VIPs | I have installed the app but never bought things from Pinduoduo because I think it is very annoying. Although it seems that we may purchase a product at a low price by asking many of our friends to click the link and cut down the rate, we help Pinduoduo to disseminate their products and promotion to our friends. In other words, they publicize their products through their users at a little cost!! In reality, the price of the product we buy is still lower than the money we finally pay for it!! So I will never buy products from Pinduoduo. |

| Construct | Items | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Product Quality (PQ) | PQ1: I perceive the PRODUCTS offered at the e-commerce platform (Taobao/Tmall/JD) to be more durable than those offered by Pinduoduo PQ2: The e-commerce platform (Taobao/Tmall/JD) PRODUCTS appear to me to be better packaged than Pinduoduo. PQ3: I perceive the PRODUCTS offered at the e-commerce platform (Taobao/Tmall/JD) to be of higher quality than those offered by Pinduoduo | Wells, Valacich and Hess [61] |

| Trust (TRS) | TRS1: The e-commerce platform that I am using now (Taobao/Tmall/JD) keeps its promises and commitment TRS2: The e-commerce platform that I am using now (Taobao/Tmall/JD) can be relied upon TRS3: The e-commerce platform that I am using now (Taobao/Tmall/JD) cares about its customers TRS4: The e-commerce platform that I am using now (Taobao/Tmall/JD) is capable of doing its job TRS5: The e-commerce platform that I am using now (Taobao/Tmall/JD) is trustworthy | Kim and Gupta [7] |

| Switching Costs (SWC) | SWC1: It would take more time and effort to switch my shopping activities from here (Taobao/Tmall/JD) to Pinduoduo SWC2: Switching my shopping activities from here (Taobao/Tmall/JD) to Pinduoduo would result in some unexpected hassle SWC3: It would be a hassle for me to switch my shopping activities from here (Taobao/Tmall/JD) to Pinduoduo SWC4: The costs in time, money, and effort to switch my shopping activities from here (Taobao/Tmall/JD) to Pinduoduo are high SWC5: All things considered, I would lose a lot if I were to switch my shopping activities from here (Taobao/Tmall/JD) to Pinduoduo | Kim and Gupta [7] |

| Relative Attractiveness (REL) | REL1: Compared to shopping at Pinduoduo, the e-commerce platform that I am using now (Taobao/Tmall/JD) would be more advantageous to me REL2: Compared to shopping at Pinduoduo, the e-commerce platform that I am using now (Taobao/Tmall/JD) would be more appealing to me REL3: Compared to shopping at Pinduoduo, the e-commerce platform that I am using now (Taobao/Tmall/JD) would be more satisfactory to me REL4: Overall, it would be better for me to shop from the e-commerce platform that I am using now (Taobao/Tmall/JD) than from Pinduoduo | Kim and Gupta [7] |

| Psychological Risk (PSYR) | PSYR1: Pinduoduo will not fit well my self-image or self-concept (Low/high) PSYR2: The usage of Pinduoduo would lead to a psychological loss for me because it would not fit well my self-image or self-concept. (Improbable/probable) | Featherman and Pavlou [11] |

| Social Risk (SOR) | SOR1: What are the chances that using Pinduoduo will negatively affect the way others think of you? (Low/high social risk) SOR2: My signing up for and using Pinduoduo would lead to a social loss for me because my friends and relatives would think less highly of me (Improbable/probable) SOR3: Recommending to purchase something together with my friends and relatives in Pinduoduo makes them thinking that I am annoying (Improbable/probable) | Featherman and Pavlou [11] |

| Privacy Risk (PRR) | PRR1: What are the chances that using Pinduoduo will cause you to lose control over the privacy of your payment information? (Improbable/probable) PRR2: My signing up for and using Pinduoduo would lead to a loss of privacy for me because my personal information would be used without my knowledge (Improbable/probable) PRR3: Internet hackers (criminals) might take control of my checking account if I used Pinduoduo (Strongly disagree/ agree) | Featherman and Pavlou [11] |

| Negative WOM (NW) | NW1: I would NOT recommend Pinduoduo to other people NW2: I would tell other people negative things about Pinduoduo | Kim, Kim and Kim [30] and Kim, Chang, Wong and Park [31] |

| Consumer Resistance to Change (RST) | RST1: My preference to use my current e-commerce platform (Taobao/Tmall/JD) would not willingly change RST2: Even if close friends recommend Pinduoduo, I would not change my preference for my current e-commerce platform (Taobao/Tmall/JD) RST3: To change my preference for my current e-commerce platform (Taobao/Tmall/JD) would require major rethinking | Pritchard, Havitz and Howard [62] |

| Negative Attitude (NATT) | NATT1: I think using Pinduoduo is not a good idea NATT2: I have negative perceptions about using Pinduoduo NATT3: I am not in favor of the idea of using Pinduoduo NATT4: Using Pinduoduo never appeals to me | Ha, Kim, Libaque-Saenz, Chang and Park [63] |

| Category | Number | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 96 | 47.29% |

| Female | 107 | 52.71% | |

| Age | Below 20 | 34 | 16.75% |

| 21~30 | 154 | 75.86% | |

| 31~40 | 4 | 1.97% | |

| 40 above | 11 | 5.42% | |

| Job | Student | 152 | 74.88% |

| White collar worker | 35 | 17.24% | |

| Etc. | 16 | 7.88% | |

| Family Income | Under 10,000 Yuan | 62 | 30.54% |

| 10,001~20,000 | 49 | 24.14% | |

| 20,001~30,000 | 30 | 14.78% | |

| 30,001~50,000 | 16 | 7.88% | |

| Over 50,000 | 46 | 22.66% | |

| Number of e-commerce platform in use | 1 | 13 | 6.40% |

| 2 | 74 | 36.45% | |

| 3 | 69 | 33.99% | |

| 4 | 28 | 13.79% | |

| 5 | 19 | 9.36% | |

| Amount of money spent on e-commerce in a week | Less than 100 yuan | 44 | 21.67% |

| 100~500 | 108 | 53.20% | |

| 501~1000 | 22 | 10.84% | |

| 1001~3000 | 18 | 8.87% | |

| More than 3000 yuan | 11 | 5.42% | |

| Construct | Items | Loading | Mean (STDEV) | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQ | PQ1 | 0.92 | 5.79(1.28) | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.80 |

| PQ2 | 0.85 | 5.51(1.38) | |||||

| PQ3 | 0.91 | 5.91(1.29) | |||||

| TRS | TRS1 | 0.89 | 5.79(1.11) | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.80 |

| TRS2 | 0.91 | 5.73(1.10) | |||||

| TRS3 | 0.89 | 5.66(1.10) | |||||

| TRS4 | 0.90 | 5.78(1.12) | |||||

| TRS5 | 0.90 | 5.68(1.13) | |||||

| SWC | SWC1 | 0.81 | 5.91(1.14) | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.73 |

| SWC2 | 0.88 | 5.87(1.14) | |||||

| SWC3 | 0.89 | 5.82(1.20) | |||||

| SWC4 | 0.88 | 5.56(1.18) | |||||

| SWC5 | 0.81 | 5.36(1.39) | |||||

| REL | REL1 | 0.80 | 6.12(1.23) | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.79 |

| REL2 | 0.90 | 6.25(1.14) | |||||

| REL3 | 0.92 | 6.22(1.11) | |||||

| REL4 | 0.92 | 6.16(1.12) | |||||

| PSYR | PSYR1 | 0.96 | 5.38(1.66) | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.92 |

| PSYR2 | 0.95 | 4.93(1.77) | |||||

| SOR | SOR1 | 0.88 | 4.46(1.81) | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.77 |

| SOR2 | 0.92 | 4.00(2.01) | |||||

| SOR3 | 0.83 | 5.04(1.83) | |||||

| PRR | PRR1 | 0.92 | 4.43(1.59) | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.84 |

| PRR2 | 0.92 | 4.55(1.61) | |||||

| PRR3 | 0.90 | 4.20(1.67) | |||||

| RST | RST1 | 0.79 | 5.58(1.10) | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.73 |

| RST2 | 0.91 | 5.55(1.15) | |||||

| RST3 | 0.87 | 5.48(1.19) | |||||

| NATT | NATT1 | 0.95 | 5.20(1.70) | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.89 |

| NATT2 | 0.95 | 5.26(1.72) | |||||

| NATT3 | 0.96 | 5.11(1.75) | |||||

| NATT4 | 0.92 | 5.57(1.60) | |||||

| NW | NW1 | 0.96 | 5.30(1.87) | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.91 |

| NW2 | 0.95 | 4.69(1.91) |

| PQ | TRS | SWC | REL | PSYR | SOR | PRR | RST | NATT | NW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQ | 0.89 | |||||||||

| TRS | 0.56 (0.62) | 0.90 | ||||||||

| SWC | 0.64 (0.72) | 0.51 (0.55) | 0.85 | |||||||

| REL | 0.65 (0.73) | 0.45 (0.48) | 0.52 (0.58) | 0.89 | ||||||

| PSYR | 0.53 (0.59) | 0.28 (0.30) | 0.46 (0.50) | 0.44 (0.48) | 0.96 | |||||

| SOR | 0.35 (0.40) | 0.15 (0.17) | 0.37 (0.42) | 0.37 (0.41) | 0.61 (0.70) | 0.88 | ||||

| PRR | 0.28 (0.32) | 0.15 (0.16) | 0.38 (0.41) | 0.24 (0.27) | 0.50 (0.55) | 0.60 (0.68) | 0.92 | |||

| RST | 0.45 (0.54) | 0.36 (0.42) | 0.51 (0.59) | 0.47 (0.54) | 0.41 (0.47) | 0.33 (0.39) | 0.35 (0.41) | 0.86 | ||

| NATT | 0.57 (0.63) | 0.33 (0.34) | 0.51 (0.55) | 0.44 (0.47) | 0.66 (0.70) | 0.58 (0.63) | 0.45 (0.48) | 0.50 (0.56) | 0.94 | |

| NW | 0.49 (0.56) | 0.34 (0.38) | 0.47 (0.52) | 0.43 (0.47) | 0.52 (0.57) | 0.45 (0.51) | 0.43 (0.48) | 0.48 (0.55) | 0.72 (0.78) | 0.95 |

| Hypotheses | P. C. | t | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Product Quality → Consumer Resistance to Change | 0.04 | 0.42 | Rejected |

| H2 | Trust → Consumer Resistance to Change | 0.07 | 0.10 | Rejected |

| H3 | Switching Cost → Consumer Resistance to Change | 0.25 | 2.75 | Supported |

| H4 | Relative Attractiveness → Consumer Resistance to Change | 0.21 | 2.05 | Supported |

| H5 | Product Quality → Trust | 0.56 | 9.34 | Supported |

| H6 | Trust → Switching Cost | 0.34 | 5.18 | Supported |

| H7 | Relative Attractiveness → Switching Cost | 0.37 | 6.06 | Supported |

| H8 | Psychology Risk → Negative Attitude | 0.47 | 6.16 | Supported |

| H9 | Social Risk → Negative Attitude | 0.25 | 2.91 | Supported |

| H10 | Privacy Risk → Negative Attitude | 0.07 | 0.97 | Rejected |

| H11 | Negative Attitude → Negative Word-of-Mouth | 0.64 | 11.28 | Supported |

| H12 | Negative Attitude → Consumer Resistance to Change | 0.28 | 4.24 | Supported |

| H13 | Consumer Resistance to Change → Negative Word-of-Mouth | 0.16 | 3.39 | Supported |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, Y.; Wong, S.F.; Libaque-Saenz, C.F.; Lee, H. e-Commerce Sustainability: The Case of Pinduoduo in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4053. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154053

Chang Y, Wong SF, Libaque-Saenz CF, Lee H. e-Commerce Sustainability: The Case of Pinduoduo in China. Sustainability. 2019; 11(15):4053. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154053

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Younghoon, Siew Fan Wong, Christian Fernando Libaque-Saenz, and Hwansoo Lee. 2019. "e-Commerce Sustainability: The Case of Pinduoduo in China" Sustainability 11, no. 15: 4053. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154053

APA StyleChang, Y., Wong, S. F., Libaque-Saenz, C. F., & Lee, H. (2019). e-Commerce Sustainability: The Case of Pinduoduo in China. Sustainability, 11(15), 4053. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154053