Expansive Social Learning, Morphogenesis and Reflexive Action in an Organization Responding to Wetland Degradation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Importance of Wetlands to Company X’s Forestry Operations and its Impacts

1.2. Company X Staff Responsible for Wetland Management

1.3. Previous Wetland Capacity Building Efforts Had Not Resulted in the Expected Long Term Change

1.4. The Need for the Research

1.5. The Following Three Research Questions were Used to Guide the Research

- What tensions and contradictions exist in wetland management in a plantation forestry company? [17]

- Can expansive social learning begin to address the tensions and contradictions that exist in wetland management in a plantation forestry company, for improved sustainability practices? [17]

- Can expansive social learning strengthen organizational learning and development, enabling Company X to improve its wetland sustainability practices, and if so how does it do this? [17]

1.6. Organizational Learning

1.6.1. The ‘Split’ in Organizational Learning and the Learning Organization

1.6.2. The Popularity of the Learning Organization and Criticisms of It

1.6.3. Individual and Collective Learning in Organizations

1.6.4. The Socio-Cultural Approach to Organizational Learning

2. Methodology

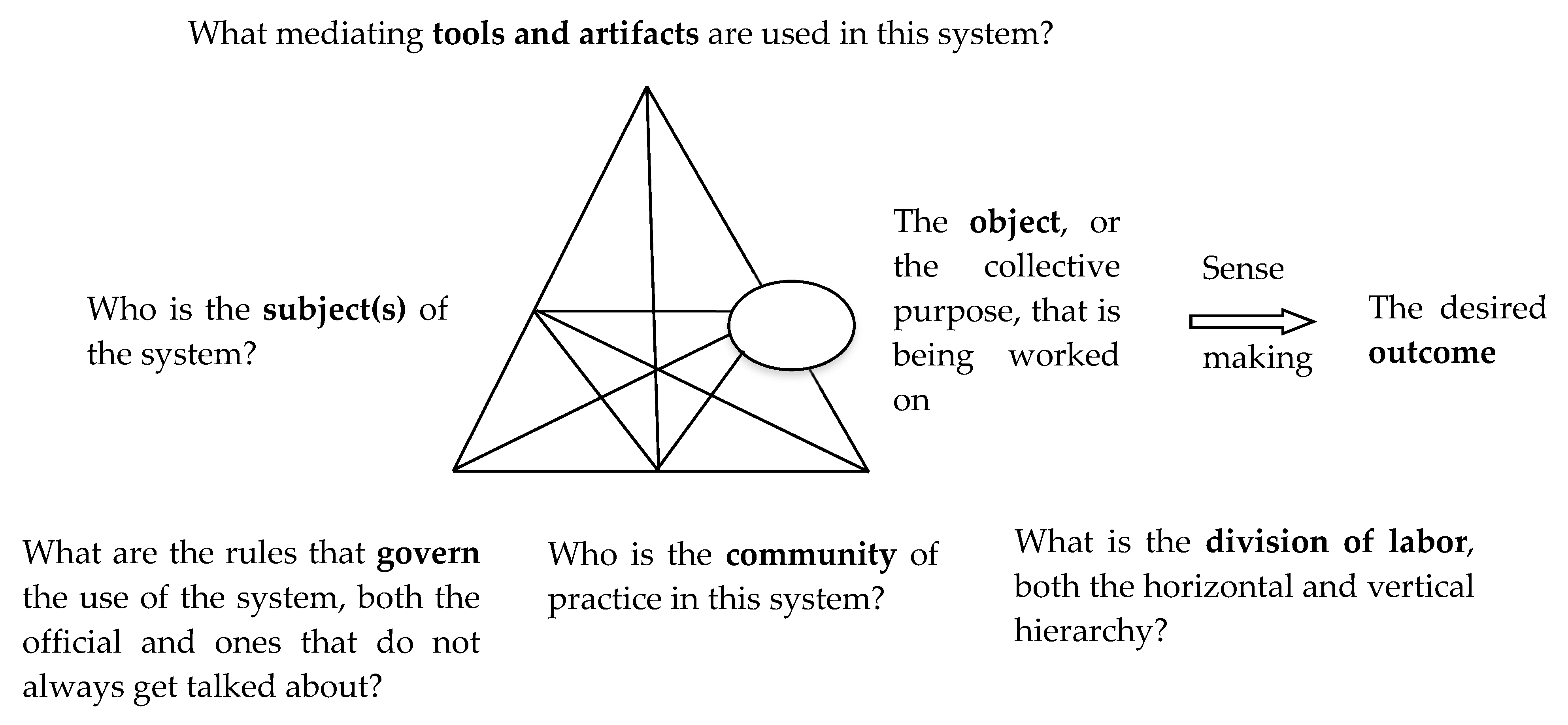

2.1. CHAT and Expansive Learning

2.1.1. Models of CHAT Used

2.1.2. A Brief Introduction to Expansive Learning

2.1.3. Expansive Learning Cycle as a Methodology for Applying CHAT and the Theory of Expansive Learning

2.2. Critical Realism

2.3. Realist Social Theory

2.3.1. Morphogenetic Framework as a Methodology for Applying Realist Social Theory

2.3.2. Highlighting the Social Learning in Expansive Learning

2.3.3. Criteria for What Constitutes Learning in the Organizational and Professional Learning Context of the Research

- Participants are able to deeply interrogate the sense, meaning, and their understanding of the context in which they work, and through this questioning begin to co-construct a broader context collectively with the other participants [37].

- Participants develop a broader orientation, perception, and understanding of the activity than that which was initially conceptualized, and additional possibilities are developed that had previously not been thought about [37].

- Participants are able to co-construct new professional practices that cross-traditional professional ‘tribal’ boundaries [53].

- Participants are able to collectively look at problems in new ways, and develop new tools to work with these problems, empowering the subjects to transform the activity system and collectively expand the object of the activity [38].

2.3.4. Research Process

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surfacing Contradictions that Inhibited Wetland Learning and Sustainability Practices

3.2. An Action Plan to Overcome the Two Prioritized Contradictions

- Adapt existing four-day induction program for new employees to be more interactive, have high employee responsibility for completing, spread out over a four-month period, contextually relevant to local area, and include an environmental module.

- Develop a toolbox of environmental education materials with guidance on appropriate education processes for their optimum use.

- Integrate new environmental courses and a toolbox into existing training program for contractors and staff.

- Foresters, community engagement facilitators, and environmental specialists to collaboratively develop and implement a wetland project in each of the five geographical areas of Company X.

- Run five field days in the five geographical areas going through management recommendations arising from the recently completed Company X State of Wetlands Health Report.

- Run field days that integrate environmental and forestry operational issues within each of the five geographical areas, as well as between them.

- Ensure that consultants conducting specialist environmental reports meet with forestry operations staff to discuss report and hear staff feedback.

- Ensure that any future Company X environmental policies and procedures to be implemented are discussed with staff on an interactive and ‘face to face’ basis, and policies or procedures are not only sent out by email for implementation.

- Meet with senior managers to encourage them to hold feedback sessions with staff providing appropriate information on any recent company business of interest.

- Report back to area and senior management on the workshop process and action plan and get commitment to its implementation.

- Meet with senior managers to encourage them to create the space for area managers to motivate their staff to implement the action plan.

3.3. Results From the Reflective Interviews Held in Phase 4

3.4. Expansive Social Learning Strengthens Organizational Learning and Development

- A deeper understanding of, for example, wetland issues resulting in knowing more about wetlands management;

- A broader understanding, demonstrating that participants have a broader knowledge of wetland management in the organizational context and how different players need to work together;

- An expanded understanding revealing that participants have built on each other’s learning and expanded their learning from knowing what they did as an individual to more collaborative, collective, social learning, demonstrating that participants have scaffolded their learning on the comments and dialogue that occurred during the expansive learning workshops;

- An increased sophistication in understanding, signifying that the learning of participants had become more multi-dimensional, more socially integrative, and more organizationally embedded. For example, as the participants began to realize that the contradictions identified inhibiting learning, they started to understand that the social structures and cultural systems of the organization were contributing to this, rather than individual personalities, and that the institutional enabling environment was not present.

3.5. Sophistication of Participant Understanding of the Inhibiting Structural and Cultural Context Increased as the Expansive Learning Cycle Progressed

3.6. The Expansive Learning Process Began to Strengthen Democratization of Decision Making

3.7. Improving Wetland Management Depends on the Critical Relationship Between Wetland Management Practices, Expansive Social Learning Processes, and Organizational Development

3.8. Five Types of Changes Emerged from the Research Ranging from Tacit Catalytic Changes to Explicit Actual Changes

3.9. Expansive Social Learning Provided a Platform to Catalyze the Morphogenesis of Organizational Learning and Development

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Latour, B. Politics of Nature. How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-674-01347-6. [Google Scholar]

- World Resources Institute, Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Wetlands and Water Synthesis; World Resources Institute, Millennium Ecosystem Assessment: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Russi, D.; Ten Brink, P.; Farmer, A.; Badura, T.; Coates, D.; Förster, J.; Kumar, R.; Davidson, N. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity for Water and Wetlands; Report; Ramsar: Gland, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kotze, D.; Breen, C.M.; Quinn, N. Wetland losses in South Africa. In Wetlands of South Africa; Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism: Pretoria, South Africa, 1995; pp. 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Driver, A.; Sink, K.; Nel, J.; Holness, S.; Van Niekerk, L.; Daniels, F.; Jonas, Z.; Majiedt, P.; Harris, L.; Maze, K. National Biodiversity Assessment 2011: An Assessment of South Africa’s Biodiversity and Ecosystems; Synthesis Report; South African National Biodiversity Institute, Department of Environmental Affairs: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tilbury, D. Education for Sustainable Development: An Expert Review of Processes and Learning; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Le Grange, L. Learning to Live with it? Troubling Education with Evidence of Global Climate Change. In Climate Change and Philosophy; Irwin, R., Ed.; Continuum: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-8264-4065-5. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.; Evely, A.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.; Glass, J.; Laing, A.; Newig, J.; Parrish, B.; Prell, C.; Raymond, C.; et al. What is Social Learning? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, H. Minding the Gap: The Role of Social Learning in Linking our Stated Desire for a More Sustainable World to our Everyday Actions and Policies. In Social Learning Towards a Sustainable World; Wals, A., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 978-90-8686-031-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsch, W.; Gosselink, J. Wetlands, 4th ed.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-471-69967-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gush, M.; Scott, D.; Jewitt, G.; Schulze, R.; Lumsden, T.; Hallowes, L.; Gorgons, A. Estimation of Streamflow Reductions Resulting from Commercial Afforestation in South Africa; Report TT173/02; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dye, P.; Jarmain, C.; Le Maitre, D.; Everson, C.; Gush, M.; Clulow, A. Modelling Vegetation Water Use for General Application in Different Categories of Vegetation; Report TT1319/1/08; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- South African Government Department of Water Affairs and Forestry. National Water Act; South African Government Department of Water Affairs and Forestry: Pretoria, South Africa, 1998.

- Lindley, D. WWF Progress Reports: January 1997 to November 2009; World Wide Fund for Nature: Cape Town, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, D.; Kotze, D.; Job, N. Company X State of Wetlands Report; Research Report; Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, D. Reflexively Exploring Better Wetland Management with Company X; Masters Coursework Assignment; Rhodes University, Education Department: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, D. Can Expansive (Social) Learning Processes Strengthen Organisational Learning for Improved Wetland Management in a Plantation Forestry Company, and If So How? A Case of Company X, South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organisation; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 0307477649. [Google Scholar]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Araujo, L. Organizational learning: Current debates and opportunities. In Organizational Learning and the Learning Organization; Easterby-Smith, M., Burgoyne, J., Araujo, L., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1999; pp. 1–21. ISBN 13 978-0761959168. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, M.; Lipshitz, R. Organisational learning: Mechanisms, culture and feasibility. Manag. Learn. 2000, 31, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkjaer, B. Organisational learning: The ‘Third Way’. Manag. Learn. 2004, 45, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapuji, H.; Crossan, M. From questions to answers: Reviewing organisational learning research. Manag. Learn. 2004, 35, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, T.; Gomes, A. Organizational learning and the learning organization: Reviewing evolution for prospecting the future. Learn. Organ. 2008, 15, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boreham, N.; Morgan, C. A socio-cultural analysis of organisational learning. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2004, 30, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, T. Thriving on Chaos: Handbook for a Management Revolution; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1987; ISBN 13 978-0060971847. [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick, T. Questioning the concept of the learning organization. Knowledge Power and Learning; Paechter, C., Preedy, M., Scott, D., Soler, J., Eds.; Paul Chapman: London, UK, 2001; pp. 74–88. ISBN 0-7619-6936-5. [Google Scholar]

- Örtenblad, A. On differences between organizational learning and learning organisation. Learn. Organ. 2001, 8, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A. Of course organisations can learn! Learn. Organ. 2005, 12, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Elkjaer, B. In search of social learning theory. In Organizational Learning and the Learning Organization; Easterby-Smith, M., Burgoyne, J., Araujo, L., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1999; pp. 75–91. ISBN 13 978-0761959168. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.; Duguid, P. Organizational learning and communities of practice: Towards a unified view of working, learning, and innovation. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Mukute, M.; Belay, M. The ‘Social’ and ‘Learning’ in Social Research: Avoiding Ontological Collapse with Antecedent Literatures as Starting Points for Research. In (Re) Views on Social Learning Literature: A Monograph for Social Learning Researchers in Natural Resources Management and Environmental Education; Lotz-Sisitka, H., Ed.; Rhodes University: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2012; ISBN 978-1-919991-81-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Roth, W. The individual/collective dialectic in the learning organisation. Learn. Organ. 2007, 14, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. Learning by Expanding: An Activity Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research; Orienta-Konsultit: Helsinki, Finland, 1987; ISBN 9519593322. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; University of Cambridge Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; ISBN 9780521423748. [Google Scholar]

- Virkkunen, J.; Kuutti, K. Understanding Organizational Learning by Focusing on “Activity Systems”. Account. Manag. Inf. Technol. 2000, 10, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. Activity Theory as a Framework for Analysing and Redesigning Work. Ergonomics 2000, 43, 960–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engeström, Y. Expansive Learning at Work: Toward an Activity Theoretical Reconceptualisation. J. Educ. Work 2001, 14, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, H. Vygotsky and Research; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008; ISBN 0-203-89179-1. [Google Scholar]

- Engeström, Y.; Kerosuo, H. From Workplace Learning to Inter-organizational Learning and Back: The Contribution of Activity Theory. J. Workplace Learn. 2007, 19, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y.; Sannino, A. Studies of expansive learning: Foundations, findings and future challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 2010, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engeström, Y.; Kerosuo, H.; Kajamaa, A. Beyond Discontinuity: Expansive Organisational Learning Remembered. Manag. Learn. 2007, 38, 310–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R. A Realist Theory of Science; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008; ISBN 0-415-45494-8. [Google Scholar]

- Delanty, G. Concepts in the Social Sciences: Philosophical and Methodological Foundations, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2005; ISBN 0-335-21722-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer, A. Realism and Social Science; Sage: London, UK, 2000; ISBN 0-7619-6124-0. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; ISBN 0-521-48176-7. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M. Being Human: The Problem of Agency; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; ISBN 0-521-79564-8. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, B.; New, C. Introduction: Realist Social Theory and Empirical Research. In Making Realism Work: Realist Social Theory and Empirical Research; Carter, B., New, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004; ISBN 0-415-30061-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wheelahan, L. Blending Activity Theory and Critical Realism to Theorise the Relationship Between the Individual and Society and the Implications for Pedagogy. Stud. Educ. Adults 2007, 39, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.; Heymann, F. Learning on the Edge: Exploring the Change Potential of Conflict in Social Learning for Sustainable Living. In Educating for a Culture of Social and Ecological Peace; Wenden, A., Ed.; University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-7914-6173-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A. Learning in a Changing World and Changing in a Learning World: Reflexively Fumbling Towards Sustainability. S. Afr. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 24, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, D. Elements of Social Learning Supporting Transformative Change. S. Afr. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 31, 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, H.; Leadbetter, J.; Warmington, P.; Edwards, A.; Martin, D.; Popova, A.; Apostolov, A.; Middleton, D.; Brown, S. Learning in and for Multi-Agency Working. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2007, 33, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmington, P.; Daniels, H.; Edwards, A.; Leadbetter, J.; Martin, D.; Middleton, D.; Parson, S.; Popova, A. Surfacing contradictions: Intervention workshops as change mechanisms in professional learning. In Proceedings of the British Education Research Association Annual Conference, Pontypridd, UK, 14–17 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Danermark, B.; Ekström, M.; Jakobsen, L.; Karlsson, J. Explaining Society; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2002; ISBN 0-203-99624-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mukute, M. Exploring and Expanding Learning Processes in Sustainable Agriculture Workplace Contexts. Ph.D. Thesis, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, T.; Craib, I. Critical realism and the social sciences. In Philosophy of Science: The Foundations of Philosophical Thought; Benton, T., Craib, I., Eds.; Palgrave: Basingstoke, UK, 2001; pp. 119–139. ISBN 13 978-0230242609. [Google Scholar]

- Bassey, M. Case Study Research in Educational Settings; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1999; ISBN 10 9780335199846. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978; ISBN 0-674-57629-2. [Google Scholar]

- Launis, K.; Virtanen, T.; Ruotsala, R. Change workshops as a tool in organisational boundary crossing. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Researching Work and Learning, Cape Town, South Africa, 2–5 December 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Engeström, Y. Enriching the theory of expansive learning: Lessons from journeys toward coconfiguration. Mind Cult. Act. 2007, 14, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoff, B.; Paradise, R.; Mejia Arauz, R.; Correa-Chavez, M.; Angelillo, C. Firsthand learning through intent participation. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 175–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndletyana, D. The impact of culture on team learning in a South African context. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2003, 5, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M. Communication and the Other: Beyond deliberative democracy. In Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political; Benhabib, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 120–135. ISBN 13 978-0691044781. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, L. Against deliberation. Political Theory 1997, 25, 347–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhabib, S. Towards a Deliberative Model of Democratic Legitimacy. In Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political; Benhabib, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996; ISBN 0-691-04479-1. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, A. Relational Agency: Learning to be a resourceful practitioner. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2005, 43, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A. Relational Agency in professional practice: A CHAT analysis. Actio Int. J. Hum. Act. Theory 2007, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Hlengwa, A. ‘Seeding Change’: 2011 International Training Programme: Education for Sustainable Development in Higher Education: Africa Regional Support. Processes and Outcomes; Research report; Rhodes University, Education Department: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| 1. Between the expectation of staff to improve wetland sustainability practices, and no recognized informal and formal learning plan/structure and learning materials in place to strengthen staff learning. |

| 2. Between individuals who recognize the importance of strengthening informal learning, and those who do not because of their attitudes/culture/individual complexity and resistance to change differs. |

| 3. Between the loss of experience and skills from staff leaving, and the lack of a structure/willingness to share wetland knowledge and skills of old timers with newcomers. |

| 4. Between community engagement facilitators, foresters and environmental specialists working in silos on their own jobs and wetland issues, and the Company X’s bigger picture of producing sustainably grown timber by staff working together as a team on common wetland issues with a more planned and integrated approach. |

| 5. Between stringent existing performance monitoring systems of e.g., silviculture, safety and alien plant clearing activities, and the lack of any wetland performance monitoring system. |

| 6. Between how Company X want to manage its wetlands, and how external influences like local communities wants to use and manage the wetland resources. |

| 7. Between the demand for environmental specialist support, and the lack of staff to supply it. |

| 8. Between having dedicated operationally aligned conservation staff to solely take responsibility for wetland and environmental management, and integrating this responsibility into the silviculture foresters’ current workload. |

| 9. Between the conservation practices that Company X has to implement, and practices of neighboring farmers who do as they like. |

| 10. Between implementing general wetland management practices and not knowing exactly what desired state the wetland is being managed for. |

| 11. Between Company X managing the land sustainably now, and how the new land reform owners will manage it in the future. |

| 12. Between senior staff talking the environmental talk, and meaningfully understanding the talk so that they can sincerely walk it. |

| Changes at End of Research | Status Quo at the Beginning of Research | Learning Criteria Satisfied (Refer to Section 2.3.3.) |

|---|---|---|

| Participants improved knowledge in understanding technical aspects of wetlands and their management. | Participants, particularly community engagement facilitators, had little understanding of the technicalities of wetlands and their management. | 3, 4 |

| Participants placed a higher value on the diverse roles of the different professional disciplines required for wetland management, and the importance of their collaboration. | Participants across the different professional disciplines (foresters, community engagement facilitators, and environmental specialists) did not value each other’s roles in wetland management. | 1, 2, 3 |

| Participants changed the way they thought about how they learnt about wetlands; how they worked and interacted with colleagues; how they understood their colleagues; and how they realized wetland management was important to their specific job descriptions. | Participants had a simplistic understanding of how they learnt about wetlands, which should be responsible for wetland management, and the importance of collaboration across professional disciplines for improved wetland management. | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| A change in discourse on intended agency was identified, signaled by an increased intent to implement more sophisticated solutions developed collaboratively by the participants. | Participants revealed many problems and tensions inhibiting wetland management but offered only simple solutions with little intent to implement them. | 4, 5, 6 |

| A changed discourse in participant conversations on how wetland and environmental learning now took place, becoming more structured, longer term, and beginning to be institutionalized in Company X. | A strong discourse of weak environmental learning that was unstructured, occurred on an ad hoc basis when the need arose, and was limited to isolated short-term courses. | 4 |

| A changed discourse in conversations that was more collaborative, interactive, and inclusive of each professional discipline. | A strong discourse of a professional discipline silo approach to communicating, learning, interacting, and working amongst staff. | 4, 5 |

| A changed discourse in conversations of what meaningful learning processes were, and which processes were important for scaffolding a change in wetland and broader environmental practices. | The discourse of learning was devoid of any understanding of learning processes, and narrowly confined to the problems of staff lacking wetland knowledge, information not being in a usable form, and staff not having the time to learn. | 4, 5 |

| Participant interaction between professional disciplines became more collaborative, personal, empathic of the other, and orientated to learning from each other. | Weak staff interaction and collaborative decision making between professional disciplines on wetland and environmental management. | 4, 5, 6 |

| Change in practice of how participants discuss/plan/implement wetland burning with staff across professional disciplines. | The poorly managed burning of wetlands was seen to be a key issue of wetland health due to foresters making unilateral decisions. | 4, 5, 6 |

| Change in the practice of how the cattle of neighboring communities graze wetlands on Company X landholdings. | Cattle grazing was identified as one of the most significant threats to the health of Company X’s wetlands. | 4, 5, 6 |

| Change in the practice of developing wetland plans together across professional disciplines. | Staff across the different professional disciplines rarely planned and worked together on wetland management issues. | 4, 5, 6 |

| Change in the practice of communicating new environmental procedure and policies, and specialist report backs. | Staff work in silos of their professional disciplines, inhibiting collaborative and integrative communications on wetland management. | 4, 5, 6 |

| Development of environmental training matrix listing training options begins to institutionalize staff environmental learning, and contractor environmental training developed and implemented. | No formally recognized informal and formal learning plan or structure and learning materials in place to strengthen environmental learning in Company X. | 6 |

| Development of innovative induction structure and processes begins to institutionalize environmental learning for new staff. | No induction process for new staff existed resulting in a loss of institutional and environmental knowledge through a lack of handover from old timers. | 3, 4, 5, 6 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lindley, D.; Lotz-Sisitka, H. Expansive Social Learning, Morphogenesis and Reflexive Action in an Organization Responding to Wetland Degradation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154230

Lindley D, Lotz-Sisitka H. Expansive Social Learning, Morphogenesis and Reflexive Action in an Organization Responding to Wetland Degradation. Sustainability. 2019; 11(15):4230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154230

Chicago/Turabian StyleLindley, David, and Heila Lotz-Sisitka. 2019. "Expansive Social Learning, Morphogenesis and Reflexive Action in an Organization Responding to Wetland Degradation" Sustainability 11, no. 15: 4230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154230

APA StyleLindley, D., & Lotz-Sisitka, H. (2019). Expansive Social Learning, Morphogenesis and Reflexive Action in an Organization Responding to Wetland Degradation. Sustainability, 11(15), 4230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154230