Social Sustainability Assessment in Livestock Production: A Social Life Cycle Assessment Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definition of the Goal and Scope

2.2. SLCA Inventory Analysis

Determination of Impact Categories, Subcategories, and Data Sources

2.3. Social Life Cycle Impact Assessment

2.4. Sensitivity Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

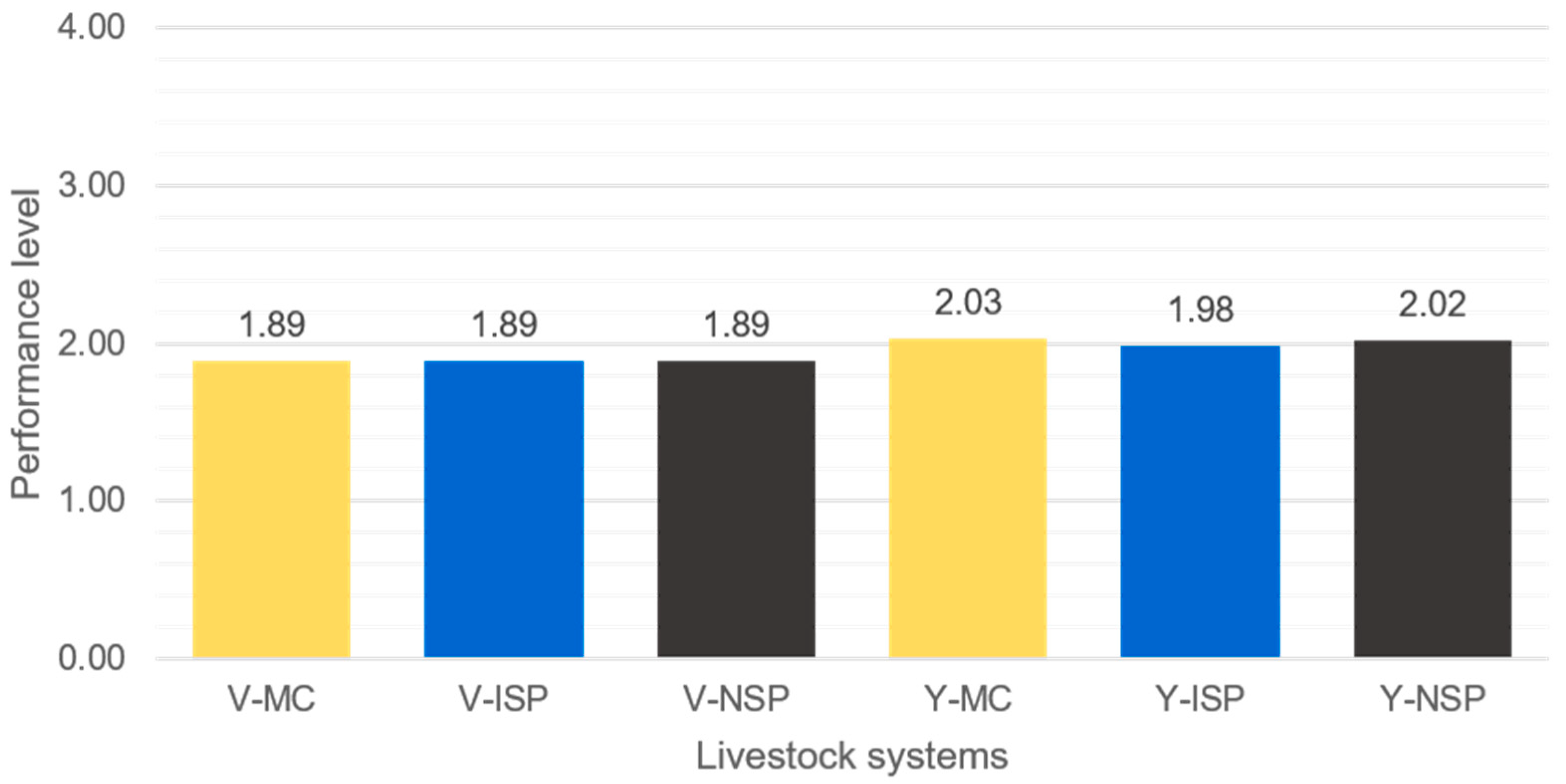

3.1. Social Impact Assessment by State

3.2. Analysis by Impact Category

3.2.1. Human Rights

Child Labor

Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining

Equal Opportunities and Discrimination

3.2.2. Health and Safety

3.2.3. Working Conditions

Fair Salary

Working Hours

Forced Labor

Social Benefits/Social Security

Job Satisfaction

3.2.4. Governance

Community Engagement

Public Commitments to Sustainability Issues

Fair Competition and Promotion of Social Responsibility

3.2.5. Socioeconomic Repercussions

Access to Material Resources and Access to Immaterial Resources

Social Acceptance

Local Employment

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis

3.3.1. Institutional Ranches

3.3.2. Private Ranches

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; de Haan, C. Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, M.; Thornton, P.K.; Gerber, P.; Reid, R.S. Livestock, livelihoods and the environment: Understanding the trade-offs. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2009, 1, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, B.; Sones, K. Poverty reduction through animal health. Science 2007, 315, 333–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Data. Livestock primary. Rome: Statistics Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2017. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Rojo-Rubio, R.; Vázquez-Armijo, J.F.; Pérez-Hernández, P.; Mendoza-Martínez, G.D.; Salem, A.Z.M.; Albarrán-Portillo, B.; González-Reyna, A.; Hernández-Martínez, J.; Rebollar-Rebollar, S.; Cardoso-Jiménez, D.; et al. Dual purpose cattle production in Mexico. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2009, 41, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIAP. Estadísticas de Producción ganadera para México. 2017. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/siap/acciones-y-programas/produccion-pecuaria (accessed on 8 February 2019).

- Ibrahim, M.; Guerra, L.; Casasola, F.; Neely, C. Importance of silvopastoral systems for mitigation of climate change and harnessing of environmental benefits. In Grassland Carbon Sequestration: Management, Policy and Economics; FAO Integrated Crop Management, FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010; Volume 11, pp. 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, N.; Pirog, R.; Rasmussen, R. Comparative life cycle environmental impacts of three beef production strategies in the Upper Midwestern United States. J. Agric. Syst. 2010, 103, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Huerta, A.; Güereca, L.P.; Rubio, M. Environmental impact of beef production in Mexico through life cycle assessment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 109, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, D.M.; De Petre, R.; Jackson, F.; Hadarits, M.; Pogue, S.; Carlyle, C.N.; Bork, E.; Mcallister, T. Value Chain: State-of-the-Art and Recommendations for Future Improvements. Animals 2017, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willers, C.D.; Maranduba, H.L.; Neto, J.A.; Rodrigues, L.B. Environmental Impact assessment of a semi-intensive beef cattle production in Brazil’s Northeast. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M.; Gongbuzeren, L.W. Greenhouse gas emission of pastoralism is lower than combined extensive/intensive livestock husbandry: A case study on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, D.S.; de Oliveira, T.E.; de Oliveira, J.M. Sustainability in the Brazilian pampa biome: A composite index to integrate beef production, social equity, and ecosystem conservation. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 98, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riethmuller, P. The social impact of livestock: A developing country perspective. Anim. Sci. J. 2003, 74, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelsen, A.; Kaimowitz, D. (Eds.) Agricultural Technologies and Tropical Deforestation; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chhipi-Shrestha, G.K.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. “Socializing” sustainability: A critical review on current development status of social life cycle impact assessment method. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2015, 17, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP/SETAC. Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products; UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. ISO 14040—Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Goal and Scope—Principles and Framework; International Organization for Standardizatio: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. ISO 14044—Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Revéret, J.-P.; Couture, J.-M.; Parent, J. Socioeconomic LCA of Milk Production in Canada; Social Life Cycle Assessment. An Insight; Muthu, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2015; pp. 25–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Holden, N.M. Social life cycle assessment of average Irish dairy farm. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 1459–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, L.; Serreli, M.; Di Cesare, S. Systematic literature review in social life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcese, G.; Lucchetti, M.; Merli, R. Social Life Cycle Assessment as a Management Tool: Methodology for Application in Tourism. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3275–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falcone, P.; Imbert, E. Social Life Cycle Approach as a Tool for Promoting the Market Uptake of Bio-Based Products from a Consumer Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S.; Keeley, A.; Sakurai, S.; Managi, S.; Norris, C. Are Renewables as Friendly to Humans as to the Environment?: A Social Life Cycle Assessment of Renewable Electricity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, L.; Hauschild, M.; Schierbeck, J. A Framework for Social Life Cycle Impact Assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2006, 11, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruviaro, C.; de Léis, C.; Lampert, V.; Jardim, B.; Dewes, H. Carbon footprint in different beef production systems on a southern Brazilian farm: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 96, 235–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.; Hernández-Gómez, I.; Romero-Montero, J. Los procesos y causas del cambio en la cobertura forestal de la Península Yucatán, México. Ecosistemas 2017, 26, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Rivera, A.; Morgan-Sagastume, J.M.; Noyola, A.; Güereca, L.P. Addressing social aspects associated with wastewater treatment facilities. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016, 57, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, G.; Altun, Ç.; Neşet, K. Social life cycle assessment of different packaging waste collection system. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 124, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. International Labor Organization Convention, No: 138. 1973. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C138 (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- UN. Global Compact. The Power of Principles. 2017. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles/principle-2 (accessed on 25 August 2018).

- ILO. Safety and Health in Agriculture Convention, No. 184. 2001. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C184 (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- CEDAW. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. UN: New York, NY, USA, 18 December 1979. Available online: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/cedaw.htm (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- ILO. Convention concerning the Rights of Association and Combination of Agricultural Workers (No. 11). 1921. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C011 (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- ILO. Convention concerning Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise. Convention 1948 (No. 87). Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:::NO:12100:P12100_ILO_CODE:C087:NO (accessed on 20 August 2018).

- ILO. Rural Workers’ Organisations Convention, No. 141. 1975. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C141 (accessed on 20 August 2018).

- ILO. Occupational Safety and Health Convention, No. 155. 1981. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=normlexpub:12100:0::no::p12100_instrument_id:312300 (accessed on 23 August 2018).

- LFT. Ley Federal del Trabajo, Diario Oficial de la Federación; Distrito Federal: México, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. ISO 26000. In Guidance on Social Responsibility; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- IFC. International Finance Corporation Performance Standar 4. World Bank Group, 2012. Available online: http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/sustainability-at-ifc/policies-standards/performance-standards/ps4 (accessed on 30 June 2018).

- WB. LAC Equity Lab: Poverty. The World Bank, 2017. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/lac-equity-lab1/poverty (accessed on 9 October 2017).

- ILO. Hours of Work (Commerce and Offices) Convention. 1930. No. 30. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312175 (accessed on 17 August 2018).

- ILO. Abolition of Forced Labour Convention. 1957. No. 105. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C105 (accessed on 25 August 2018).

- ORC International. Global Perspectives 2015: Worldwide trends in employee engagement. www.ORCInternational.com(Decente et al., n.d.)(Decente et al., n.d.)(Decente et al., n.d.) 2015. Available online: https://orcinternational.com/report/2015-worldwide-trends-in-employee-engagement/ (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Suzuki, R.; Shimodaira, H. Pvclust: An R package for assessing the uncertainty in hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1540–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2016; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 28 July 2018).

- INEGI. Censo de población y vivienda 2010. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2010/ (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- ILO. Combating child labour. A handbook for labour inspectors. International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) InFocus Programme on Safety and Health at Work and the Environment (SafeWork) International Association of Labour Inspection (IALI). 2002. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/labour-administration-inspection/resources-library/publications/WCMS_110148/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 20 August 2018).

- HSA. Farm Safety Code of Practice—Risk Assessment Document. Health and Safety Authority, 2006. Available online: https://www.hsa.ie/eng/publications_and_forms/publications/agriculture_and_forestry/farm_safety_risk_assessment_.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Franze, J.; Ciroth, A. A Comparison of Cut Roses from Ecuador and the Netherlands. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2011, 16, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandth, B. Gender identity in European family farming: A literature review. Sociol. Rural. 2002, 42, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballara, M.; Parada, S. El Empleo De Las Mujeres Rurales, 1st ed.; FAO-CEPAL: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the Seventieth Session of the United Nations General Assembly, New York, NY, USA, 21 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, P. Agricultural Workers and Their Contribution to Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development, 1st ed.; FAO-ILO-IUF. ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kallioniemi, M.K.; Raussi, S.M.; Rautiainen, R.H.; Kymäläinen, H.R. Safety and animal handling practices among women dairy operators. J. Agric. Saf. Health 2011, 17, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, M. Población Rural Y Trabajo En México, 1st ed.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. International Definitions and Prospects of Underemployment Statistics; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/statistics-and-databases/WCMS_091440/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 6 January 2019).

- Laca, A.; Mejía, C.; Gondra, J. Propuesta de un modelo para evaluar el bienestar laboral como componente de la salud mental. Psicol. Salud 2006, 16, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Abrajan, M.G.; Contreras, P.; Montoya, S. Grado de Satisfacción Laboral y Condiciones de Trabajo: Una Exploración Cualitativa. Job satisfaction degree and working conditions: A qualitative exploration. Enseñanza e Investigación en Psicología 2009, 14, 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Acker, J. The effect of organizational conditions (role conflict, role ambiguity, opportunities for professional development, and social support) on job satisfaction and intention to leave among social workers in mental health care. Community Ment. Health J. 2004, 40, 65–73. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:COMH.0000015218.12111.26 (accessed on 20 March 2019). [CrossRef]

- Siebert, A.; Bezama, A.; O’Keeffe, S.; Thrän, D. Social life cycle assessment indices and indicators to monitor the social implications of wood-based products. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4074–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHRC. Promotion and Protection of All Human Rights, Civil, Political, Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Including the Right to Development; United Nations Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerlan, 2008; Available online: https://business-humanrights.org/sites/default/files/reports-and-materials/Ruggie-report-7-Apr-2008.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2018).

- PNUD. Informe Sobre Desarrollo Humano México 2016; México, D.F., Ed.; Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: http://www.mx.undp.org/ (accessed on 15 February 2019).

- CDI, 2017. Sistema de indicadores sobre la población indígena de México, based on: INEGI, Encuesta Intercensal, México. 2015. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/inpi/documentos/indicadores-socioeconomicos-de-los-pueblos-indigenas-de-mexico-2015 (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- CONEVAL. Medición de La Pobreza. 2019. Available online: https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/MP/Paginas/AE_pobreza_2016.aspx, (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Dumont, A.; Baret, P. Why working conditions are a key issue of sustainability in agriculture? A comparison between agroecological, organic and conventional vegetable systems. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 56, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIT. Transición a la formalidad en la economía rural informal. Organización Internacional del Trabajo. 2017. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/economic-and-social-development/rural-development/WCMS_437218/lang--es/index.htm (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Yúnez, A.; Taylor, E. The determinants of nonfarm activities and incomes of rural households in Mexico, with emphasis on education. World Dev. 2001, 29, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Impact Categories | Impact Subcategories | Inventory Indicators | Reference Framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human rights | Child labor (W) | Number of people under 15 working | ILO, Convention No. 138 [31] UN Global Compact, Principles 1 and 5 [32] ILO Convention No. 184 [33] |

| Equal opportunities/discrimination (W) | Number of incidents of discrimination | CEDAW [34] | |

| Percentage of working women | |||

| Freedom of association and collective bargaining (W) | Percentage of workers who are members of a labor union | ILO, Convention No. 11 [35] ILO, Convention No. 87 [36] UN Global Compact, Principle 3 [32] ILO, Convention No. 141 [37] | |

| Health and safety | Health and safety (W) | Number of work accidents | ILO, Convention No. 155 [38] ILO, Convention No. 184 [33] LFT [39] |

| Presence of a formal policy concerning health and safety | |||

| Safe and healthy living conditions (Lc) | Number of programs to improve the health or safety of the community | ISO:26000 [40] UN Global Compact, Principle 1 [32] IFC Performance Standard 4 [41] | |

| Working Conditions | Fair salary (W) | Average household income per capita from the income of the worker | WB [42] |

| Working hours (W) | Average number of hours worked/week | ILO, Convention No. 30 [43] ILO, Convention No.184 [33] LFT [39] | |

| Forced labor (W) | Number of hours of forced labor identified during the study period | ILO, Convention No. 105 [44] UN Global Compact, Principle 4 [32] | |

| Social benefits/social security (W) | Average percentage of workers who receive the minimum social benefits established by law (vacation, days off, Christmas bonus, social security, flexible hours, written contract, and training) | LFT [39] | |

| Job satisfaction (W) | Percentage of workers who would change jobs | ORC International [45] | |

| Governance | Community engagement (Lc) | Existence of a mechanism to receive and take into account the opinion of the community | ISO:26000 [40] IFC Performance Standard 4 [41] |

| Public commitments to sustainability issues (S) | Presence of documents concerning agreements on sustainability issues available to the public | ISO:26000 [40] IFC Performance Standard 4 [41] | |

| Fair competition (Vc) | Documented declaration or procedures (policies, strategies, etc.) to avoid becoming involved or being accomplices in anticompetitive behavior | UN Global Compact, Principle 2 [32] | |

| Promoting social responsibility (Vc) | Among suppliers, the presence of an explicit code of conduct that protects the human rights of workers | ISO:26000 [40] | |

| Socioeconomic repercussions | Access to material resources (Lc) | Number of programs that aim to create infrastructure for the mutual benefit of the organization and the community | UN Global Compact, Principle 2 [32] |

| Access to immaterial resources (Lc) | Number of education programs for the community | ISO:26000 [40] | |

| Local employment (Lc) | Percentage of workers belonging to local communities | LFT [39] | |

| Social acceptance (Lc) | Percentage of respondents who consider the existence of ranches to be positive for the community | IFC Performance Standard 4 [41] UN Global Compact, Principle 1 [32] |

| Level | Scale | Social Performance | Rating Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Outstanding | Proactive behavior in relation to the reference value |

| 3 | Acceptable | Meets the reference value |

| 2 | Poor | Does not meet the reference value |

| 1 | Very poor | Does not meet the reference value and operation of the organization in an unfavorable context (i.e., physical, psychological, or security risks, or in violation of human rights) |

| 0 | No data | No reported data |

| Subcategory/Inventory Indicator | VMC1 | YMC2 | YMC3 | VISP1 | YISP2 | YISP3 | YISP4 | VNSP1 | VNSP2 | YNSP3 | YNSP4 | YNSP5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freedom of association and collective bargaining (W) | ||||||||||||

| Percentage of workers who are members of a labor union | 0.00 (1) | 0.00 (1) | 0.00 (1) | 0.00 (1) | 0.00 (1) | 0.00 (1) | 0.00 (1) | 0.00 (1) | 0.00 (1) | 0.00 (1) | 0.00 (1) | 0.00 (1) |

| Child labor (W) | ||||||||||||

| Number of people under 15 working | 1.00 (2) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 2.00 (1) | 0.00 (3) |

| Fair salary (W) | ||||||||||||

| Average household income per capita from the income of the worker | 1.25 (1) | 2.50 (2) | 1.59 (1) | 1.97 (1) | 1.74 (1) | 1.66 (1) | 1.51 (1) | 1.89 (1) | 1.00 (1) | 2.13 (1) | 0.95 (1) | 0.94 (1) |

| Working hours (W) | ||||||||||||

| Average number of hours worked/week | 63 (1) | 64 (1) | 44 (3) | 52 (2) | 63 (1) | 36 (1) | 48 (3) | 49 (2) | 40 (1) | 57 (2) | 31.50 (1) | 35 (1) |

| Forced labor (W) | ||||||||||||

| Number of hours of forced labor identified during the study period | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (3) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rivera-Huerta, A.; Rubio Lozano, M.d.l.S.; Padilla-Rivera, A.; Güereca, L.P. Social Sustainability Assessment in Livestock Production: A Social Life Cycle Assessment Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4419. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164419

Rivera-Huerta A, Rubio Lozano MdlS, Padilla-Rivera A, Güereca LP. Social Sustainability Assessment in Livestock Production: A Social Life Cycle Assessment Approach. Sustainability. 2019; 11(16):4419. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164419

Chicago/Turabian StyleRivera-Huerta, Adriana, María de la Salud Rubio Lozano, Alejandro Padilla-Rivera, and Leonor Patricia Güereca. 2019. "Social Sustainability Assessment in Livestock Production: A Social Life Cycle Assessment Approach" Sustainability 11, no. 16: 4419. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164419

APA StyleRivera-Huerta, A., Rubio Lozano, M. d. l. S., Padilla-Rivera, A., & Güereca, L. P. (2019). Social Sustainability Assessment in Livestock Production: A Social Life Cycle Assessment Approach. Sustainability, 11(16), 4419. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164419