“We Are Prisoners in Our Own Homes”: Connecting the Environment, Gender-Based Violence and Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights to Sport for Development and Peace in Nicaragua

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sport and the Environment

2.1.1. SDP and The Environment: A Call for Feminist Approaches

Instead of having to pay fees to play soccer in MYSA, which they could hardly afford, Nairobi’s poorest slum children would do clean-up projects. Each successful completion of the approved clean-up project would earn a team six points (equivalent to two wins) in league standings. While initially seeming strange to the residents of Mathare, has now become commonplace, that is, on weekends and on holidays, teams of youths are seen with hoes, shovels and wheelbarrows clearing garbage and digging ditches. This remarkable initiative was recognized at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro with a UNEP Global 500 Award. [24] (p. 832)

Subvert the foundational linear-teleological undertones of modernisation [sic] or ‘progress’ and suggest a more enduring standard of living, the term has become so commonplace that it is now too vague to talk of ‘sustainable development’ without specific reference to the environment, although it can also refer to the social, economic and even political. [28] (p. 926)

2.1.2. Sport, Gender, Development and the Environment

2.2. Connecting Gender-Based Violence, Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights, and Sport

Linking Gender-Based Violence Prevention, Sexual and Reproductive Health, and the Environment

Discursively link population growth, environmental problems, and family planning to women’s empowerment, they construct a model of an ideal sustainable development subject: a moral agent who manages her fertility and the environment responsibly through contraceptive use for the greater good. ([76] p. 346)

Within Latino cultures, for example, the cult of machismo may make men and not women more likely to suffer the loss of life during an event, whatever their relative poverty, due to their socially constructed roles and associated riskier behaviour patterns in the face of danger. (p. 628)

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Postcolonial Feminist Political Ecology Theory

Natural resource control, distribution, and access as a way to help ‘mainstream’ gender in development policy and planning, in a more meaningful and plural fashion […] compelling feminist political ecologists to see race in places we tend to take as race-less, such as ‘the environment’. [6] (p. 156)

3.2. (Postcolonial) Feminist Sociomaterialisms

3.3. SDP, Postcolonial Feminist Sociomaterialisms and the Environment

If a hallmark of [physical cultural studies] research is its focus on linking theory, empiricism, and interventionist work, the last of these elements surely requires a broadened view of whom (or what) interventionism might affect and what kinds of inequalities require interventionism in the first place. This would mean bringing new attention to non-human elements of the physical (environment) and perhaps inspiring empathy for ‘things’ – and thus a better and broader sense of interconnectedness and inclusivity. [21] (p. 920).

4. Nicaragua: The Women’s Movement, Political Foundations, Sport and Climate Change

Most of the real privileges of the colonial epoch are today gone, but the ranking and sorting remains, supported less by economic rights per se and more by the rights and values held to be implicit in the color terms themselves: a colonialism of bodies, trapped by and in discourse; a hegemony, not of colonists, nor even of colonialism per se any more, but of the values produced by colonialism (p. 349, italics added for emphasis).

5. Methodology

5.1. Background on Case Study Organization

5.2. Postcolonial Feminist Participatory Action Research (PFPAR): Photovoice, Photocollaging & Digital Storytelling

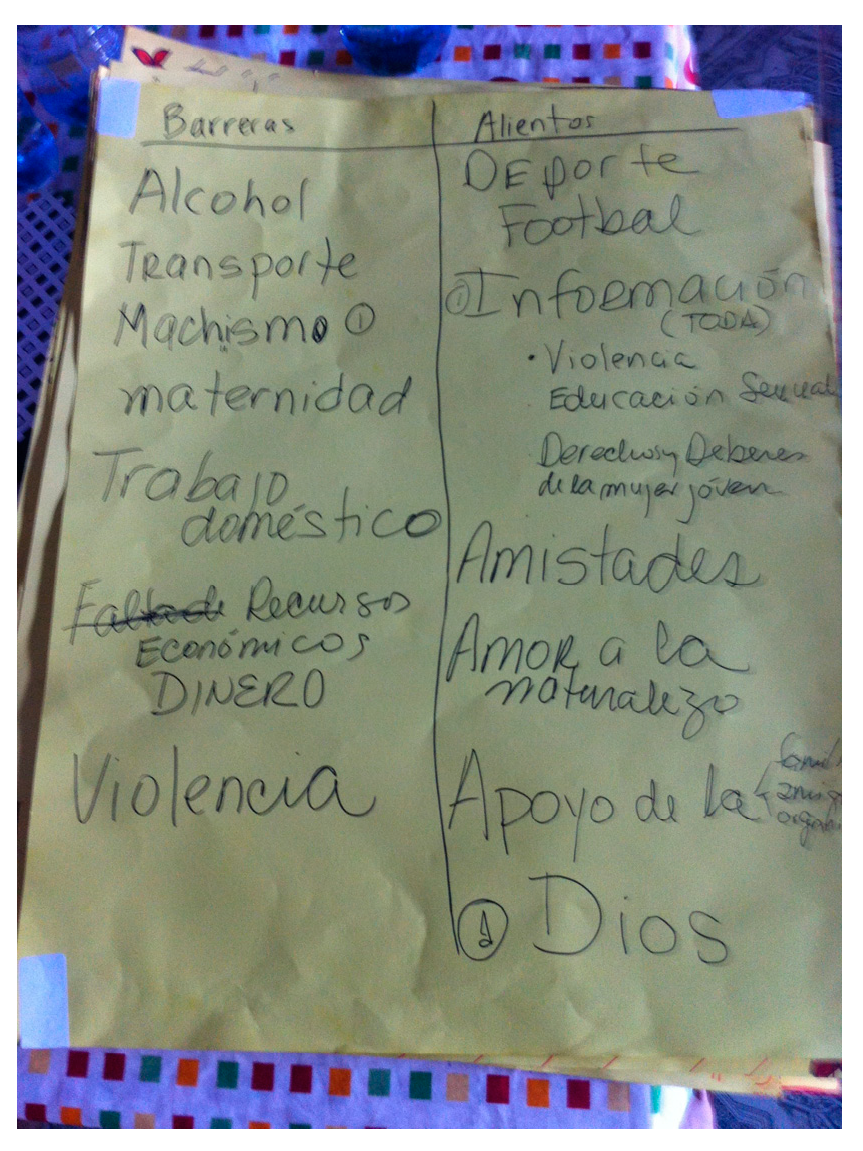

6. Findings

6.1. The Feminization of Environmental Responsibility through SGD

Through football, we can ensure that we have good practices in relation to the environment, to raise awareness within the community. That we should keep safe and clean the environment […] I’m talking about the environment when the girls are going to play, if they bring in any plastic bag, if they have a water bottle, not to throw it to the floor, but to dispose of their garbage as it should be. And to ensure that the football field is maintained clean, so we have a healthy environment.

6.2. Impelling Hegemonic Gender Identities and Locating Women’s Environmental Knowledge

One of the examples that the information [LNGO] gave us through the workshops and at the different festivals is how to use the condom to prevent pregnancy, and also the sexually transmitted diseases, how to prevent that. Something else is what we can do with the plastic, with garbage. How can we reuse that? We can work, or we can build a garbage dump, or you can sweep it up.

For us—we as [LNGO], it is important to create the link, to relate those issues. As a criteria that we had set up in the activities, we don’t use disposable dishes or disposable plates or cups because that creates garbage. And oftentimes this is garbage that is not easily recyclable or perhaps is not. So these are issues that are—have a relationship with health, with taking care of us. But also taking care of the environment in which we live. It’s part of the living together, the harmonious relationship in which we need to live. It’s like a triangle. We, men, environment, it’s creating an equal footing. It is the nation among men and women, but also with the environment. Creating a balance, an equal footing among those three. We always just try to do that, to preserve the environment.

6.3. “They Chop the Trees”: Landslides, Cement Barriers, and the Gendered Implications of Climate Change

6.4. Non-human Actors, Social Isolation and the Gendered Climate Change

I took this picture in my community. One of the difficulties that we face on this road, there is a gorge which is very bad, very deep. And there are difficulties, many of them, because we transport ourselves in a vehicle and the lane is very narrow, so just passing through it is very difficult. And we have to pass through there if we want to play when we go far away [31] (p. 284).

I like to talk about violence, and I like to learn about my health and the health of the body. How we as girls take care of your own body. They [LNGO] really give us good training workshops. We do a lot of games. LNGO talks to us about sexuality. They teach us how to prevent diseases, how to ensure that our body’s kept clean, what are some of the things that we need to do, how to prevent diseases. And if we’re talking about sexual topics, how to prevent pregnancy, unwanted pregnancies.

7. Discussion

Being a girl is a way of being taught what it is to have a body; you are being told; you will receive my advances; you are an object; thing, nothing. To become a girl is to learn to expect such advances; to modify your behaviour in accordance […] Indeed, if you do not modify your behaviour in accordance, if you are not careful and cautious, you can be made responsible for the violence directed toward you. (p. 26)

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonda, N. Revealing the patriarchal sides of climate change adaptation through intersectionality: A case study from Nicaragua. In Understanding Climate Change through Gender Relations; Buckingham, S., Le Masson, V., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 173–189. ISBN 978-131-566-160-5. [Google Scholar]

- Women Win. Intro. Available online: https://guides.womenwin.org/gbv/intro (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Gonda, N. Climate change, “technology” and gender: “Adapting women” to climate change with cooking stoves and water reservoirs. Gender Technol. Dev. 2016, 20, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosa, C.S.; Tuana, N. Mapping a research agenda concerning gender and climate change: A review of the literature. Hypatia 2014, 29, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulianotti, R.; Darnell, S.; Collison, H.; Howe, P.D. Sport for development and peace and the environment: The case for policy, practice, and research. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollett, S. Gender’s critical edge: Feminist political ecology, postcolonial intersectionality, and the coupling of race and gender. In The Routledge Handbook of Gender and Environment; MacGregor, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 146–159. ISBN 0-415-70774-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mollett, S.; Faria, C. Messing with gender in feminist political ecology. Geoforum 2013, 45, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmonde, K.; Jette, S. Fatness, fitness, and feminism in the built environment: Bringing together Physical Cultural Studies and sociomaterialisms, to study the “obesogenic environment”. Sociol. Sport J. 2016, 35, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosz, E. Feminism, materialism, and freedom. In New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency and Politics; Coole, D., Frost, S., Eds.; Duke University Press: London, UK, 2010; pp. 139–158. ISBN 978-082-239-299-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, L. Gender, UN Peacekeeping and the Politics of Space; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-019-069-943-7. [Google Scholar]

- True, J. The Political Economy of Violence Against Women; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-019-975-591-2. [Google Scholar]

- UN Inter-Agency Task Force on SDP. Sport for Development and Peace: Towards Achieving the Millennium Development Goals. 2005. Available online: www.sportanddev.org (accessed on 4 November 2016).

- Cantelon, H.; Letters, M. The making of the IOC environmental policy as the third dimension of the Olympic movement. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2000, 35, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernushenko, D. Greening our Games: Running Sports Events and Facilities that won’t Cost the Earth; Centurion Publishing & Marketing: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1994; ISBN 0-9697571-5-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lenskyj, H.J. Sport and corporate environmentalism: The case of the Sydney 2000 Olympics. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 1998, 33, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A.P.J. Sustainability as global attractor: The greening of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Glob. Netw. 2010, 10, 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddart, M.J. “If we wanted to be environmentally sustainable, we’d take the bus”: Skiing, mobility and the irony of climate change. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2011, 18, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Millington, B.; Wilson, B. Super intentions: Golf course management and the evolution of environmental responsibility. Sociol. Q. 2013, 54, 450–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millington, B.; Wilson, B. An unexceptional exception: Golf, pesticides, and environmental regulation in Canada. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2014, 51, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millington, B.; Wilson, B. Golf and the environmental politics of modernization. Geoforum 2015, 66, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millington, B.; Wilson, B. Contested terrain and terrain that contests: Donald Trump, golf’s environmental politics, and a challenge to anthropocentrism in Physical Cultural Studies. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2017, 52, 910–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B. Sport and Peace: A Sociological Perspective; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, B. A new social movement: Sport for development and peace. Sport Soc. 2008, 11, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, O. Sport and development: The significance of mathare youth sports association. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2000, 21, 825–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, B.; Roy, G. Exploring critical alternatives for youth development through Lifestyle Sport: Surfing and community development in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millington, R.; Darnell, S.; Millington, B. Ecological modernization and the olympics: The case of golf and Rio’s ‘Green’ Games. Sociol. Sport J. 2018, 35, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; ISBN-10: 0807047090. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, N.; Bawa, S. A post-development hoax? (Re)-examining the past, present and future of development studies. Third World Q. 2014, 35, 922–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanes, R.; Magee, J. Promoting gender empowerment through sport? Exploring the Experiences of Zambian female footballers. In Global Sport-For-Development; Adair, D., Schulenkorf, N., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 134–154. [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra, M. Dilemmas and opportunities in gender and sport-in-development. In Sport and International Development; Levermore, R., Beacom, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 124–155. [Google Scholar]

- Hayhurst, L.M.C.; Sundstrom, L.M.; Arksey, E. Navigating norms: Charting gender-based violence prevention and sexual health rights through global-local sport for development and peace relations in Nicaragua. Sociol. Sport J. 2018, 35, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M. Imagining neoliberal feminisms? Thinking critically about the US diplomacy campaign, ‘Empowering women and girls through sports’. Sport Soc. 2015, 18, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, S.D.; Frisby, W. Just be empowered: How girls are represented in a sport for development and peace HIV/AIDS prevention manual. Sport Soc. 2015, 18, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershow, R.B.; Gannett, K.; Merrill, J.; Braunschweig Kaufman, E.; Barkley, C.; DeCelles, J.; Harrison, A. Using soccer to build confidence and increase HCT uptake among adolescent girls: A mixed-methods study of an HIV prevention programme in South Africa. Sport Soc. 2015, 18, 1009–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szto, C. Serving up change? Gender mainstreaming and the UNESCO-WTA partnership for global gender equality. Sport Soc. 2015, 18, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, M. The value of female sporting role models. Sport Soc. 2015, 18, 968–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawansky, M.; Mitra, P. Family matters: Studying the role of the family through the eyes of girls in an SFD programme in Delhi. Sport Soc. 2015, 18, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.D.; Dennehy, J. Body projects: Making, remaking, and inhabiting the woman’s futebol body in Brazil. Sport Soc. 2015, 18, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, H. Action sports for youth development: critical insights for the SDP community. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2016, 8, 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, H.; Chawansky, M. The ‘girl effect’ in action sports for development: The case of the female practitioners of Skateistan. In Women in Action Sport Cultures: Identity, Politics and Experience; Thorpe, H., Olive, R., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 133–152. ISBN 978-1-137-45797-4. [Google Scholar]

- Brymer, E.; Downey, G.; Gray, T. Extreme sports as a precursor to environmental sustainability. J. Sport Tour. 2009, 14, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Women Win. What is Gender-Based Violence (GBV)? 2018. Available online: http://guides.womenwin.org/gbv/conflict/context/what-is-gender-based-violence (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- UN Women. Facts and Figures: Ending Violence Against Women. 2018. Available online: http://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures (accessed on 29 June 2019).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and non-partner sexual violence. 2013. Available online: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564625/en (accessed on 12 January 2019).

- Mitchell, C.; de Lange, N. Interventions that address sexual violence against girls and young women: Mapping the issues. Agenda 2015, 29, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simister, J. More than a billion women face ‘Gender based violence’: Where are most victims? J. Family Violence 2012, 27, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, S.E. The Seductions of Quantification: Measuring Human Rights, Gender Violence, and Sex Trafficking; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-022-626-114-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brackenridge, C.; Fasting, K.; Kirby, S.; Leahy, T. Protecting Children from Violence in Sport: A Review with a Focus on Industrialized Countries; UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre: Florence, Italy, 2010; ISBN 978-88-89129-96-8. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. 1995. Available online: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/pdf/BDPfA%20E.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Galati, A.J. Onward to 2030: Sexual and reproductive health and rights in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2015, 18, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bobel, C. The Managed Body: Developing Girls and Menstrual Health in the Global South; Palgrave MacMillian: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-3-319-89414-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sistersong. Reproductive Justice. 2019. Available online: https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Brackenridge, C.; Bringer, J.D.; Bishopp, D. Managing cases of abuse in sport: Child abuse review. J. Br. Assoc. Study Prev. Child Abuse Negl. 2005, 14, 259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Fasting, K.; Brackenridge, C.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. Experiences of sexual harassment and abuse among Norwegian elite female athletes and nonathletes. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2003, 74, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, A.E.; Kerr, G.A. Defining and categorizing emotional abuse in sport. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2008, 8, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cense, M.; Brackenridge, C. Temporal and developmental risk factors for sexual harassment and abuse in sport. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2001, 7, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasting, K.; Brackenridge, C.; Walseth, K. Consequences of sexual harassment in sport for female athletes. J. Sex. Aggress. 2002, 8, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fasting, K. Research on Sexual Harassment and Abuse in Sport. 2005. Available online: http://www.idrottsforum.org/articles/fasting/fasting050405.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- Rock, K.; Valle, C.; Grabman, G. Physical inactivity among adolescents in Managua, Nicaragua: A cross-sectional study and legal analysis. J. Sport Dev. 2013, 1, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Usher, L.E.; Kersetter, D. (Surfistas locales: Transnationalism and the construction of surfer identity in Nicaragua. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2015, 39, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhurst, L.M.C. Image-ining resistance: Using postcolonial feminist participatory action research and visual research methods in sport for development and peace. Third World Themat. 2017, 2, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Women Win. GBV Guide. 2019. Available online: http://guides.womenwin.org/gbv (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Brecklin, L.R. Evaluation outcomes of self-defense training for women: A review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2008, 13, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.A. The roots of resistance to women’s self-defense. Violence Against Women 2009, 15, 574–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ingen, C. Spatialities of anger: Emotional geographies in a boxing program for survivors of violence. Sociol. Sport J. 2011, 28, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ingen, C. Shape your life and embrace your aggression: a boxing project for female and trans survivors of violence. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2011, 20, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ingen, C. Getting lost as a way of knowing: The art of boxing within Shape Your Life. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2016, 8, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, S.D. Look after yourself, or look after one another? An analysis of life skills in sport for development and peace HIV prevention curriculum. Sociol. Sport J. 2014, 31, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwaanga, O. Sport for addressing HIV/AIDS: Explaining our convictions. Leis. Stud. Assoc. Newsl. 2010, 85, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Mwaanga, O.; Banda, D. A postcolonial approach to understanding sport-based empowerment of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in Zambia: The case of the cultural philosophy of Ubuntu. J. Disabil. Relig. 2014, 18, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, A.; Chawansky, M. Taking sex off the sidelines: Challenging heteronormativity within ‘Sport in Development’research. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2016, 51, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhind, D.; Brackenridge, C.; Kay, T.; Owusu-Sekyere, F. Child protection and SDP: The post-MDG agenda for policy, practice and research. In Beyond Sport for Development and Peace: Transnational Perspectives on Theory, Policy and Practice; Hayhurst, L.M.C., Kay, T., Chawansky, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 72–86. ISBN 978-1138806672. [Google Scholar]

- Hayhurst, L.M.C.; MacNeill, M.; Kidd, B.; Knoppers, A. Gender-based violence and Sport for Development and Peace: Questions, concerns and cautions emerging from Uganda. Women Stud. Int. Forum 2014, 47, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora-Jonnsson, S. Forty years of gender research and environmental policy: Where do we stand? Women Stud. Int. Forum 2014, 47, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonders, N.A.; Danner, M.J.E. Gendering climate change: A feminist criminological perspective. Crit. Criminol. 2015, 23, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasser, J. Sexual stewardship: environment, development, and the gendered politics of population. In The Routledge Handbook of Gender and Environment; MacGregor, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 345–357. ISBN 0-415-70774-9.345-357. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, M. The Economization of Life; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-8223-6345-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, S. Women, Poverty and Disasters: Exploring the Links through Hurricane Mitch in Nicaragua. In The International Handbook of Gender and Poverty: Concepts, Research, Policy; Chant, S., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2010; pp. 516–522. [Google Scholar]

- Resurrección, B.P. Gender and the environment in the Global South: From ‘women, environment and development’ to feminist political ecology. In The Routledge Handbook of Gender and Environment; MacGregor, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 71–85. ISBN 0-415-70774-9.345-357. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, B. The gender and environment debate: Lessons from India. Fem. Stud. 1992, 18, 119–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, S. Gender and environment: an introduction. In The Routledge Handbook of Gender and Environment; MacGregor, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–25. ISBN 0-415-70774-9.345-357. [Google Scholar]

- Cannella, G.S.; Manuelito, K.D. Feminisms from unthought locations: Indigenous worldviews, marginalized feminisms, and revisioning anticolonial social science. In Handbook of Critical and Indigenous Methodologies; Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y., Smith, L.T., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2008; pp. 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.; MacGregor, S. The Death of Nature: foundations of ecological feminist thought. In The Routledge Handbook of Gender and Environment; MacGregor, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 43–54. ISBN 0-415-70774-9.345-357. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, S. A stranger silence still: The need for feminist social research on climate change’. Sociol. Rev. 2018, 57, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coole, D.; Frost, S. Introducing the new materialisms. In New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency and Politics; Coole, D., Frost, S., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2010; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. Sciences from Below: Feminisms, Postcolonialities, and Modernities; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. Introduction. beyond postcolonial theory: Two undertheorized perspectives on science and technology. In The Postcolonial Science and Technology Studies Reader; Harding, S., Ed.; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2011; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Alaimo, S.; Hekman, S. Introduction: Emerging models of materiality in feminist theory. In Material Feminisms; Alaimo, S., Hekman, S., Eds.; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2008; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Darnell, S.C.; Giulianotti, R.; Howe, P.D.; Collison, H. Re-assembling sport for development and peace through actor network theory: Insights from Kingston, Jamaica. Sociol. Sport J. 2018, 35, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, Y.A.; Arora, S. Nonhumans in the practice of development: Material agency and friction in a small-scale energy program in Indonesia. Geoforum 2016, 70, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, T. The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Disney, L. Women’s Activism and Feminist Agency in Mozambique and Nicaragua; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, R.N. Skin color, race, and racism in Nicaragua. Ethnology 1991, 30, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouvet, E. Extraordinary aid and its shadow: The significance of gratitude in Nicaraguan humanitarian healthcare. Critique Anthropol. 2016, 36, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, D.; Hutfils, M.-L.; Winges, M. Global Climate Risk Index 2019: Who Suffers Most from Extreme Weather Events? Weather-Related Loss Events in 2017 and 1998 to 2017. Available online: https://germanwatch.org/sites/germanwatch.org/files/Global%20Climate%20Risk%20Index%202019_2.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- USAID. Nicaragua Climate Change Risk Profile. 2017. Available online: https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/2017_USAID_Nicaragua%20Climate%20Change%20Risk%20Profile.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2019).

- Pena, N.; Maiques, M.; Castillo, G.E. Using rights-based and gender-analysis arguments for land rights for women: Some initial reflections from Nicaragua. Gender Dev. 2008, 16, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo del Arco, T. Políticas de g´Enerodurante el Liberalismo: Nicaragua, 1893–1909; UCA: Managua, Nicaragua, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Collinson, H. Women and Revolution in Nicaragua; Zed Press: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. Country Chapters—Nicaragua. 2019. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/nicaragua#9b8180 (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Jubb, N. Love, family values and reconciliation for all, but what about rights, justice and citizenship for women? The FSLN, the women’s movement, and violence against women. Bull. Latin Am. Res. 2014, 33, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radcliffe, S. Gender and postcolonialism. In Routledge Handbook of Gender and Development; Coles, A., Gray, L., Momsen, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 35–47. ISBN 978-0415829083. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, C.; de Lange, N.; Molestsane, R. Participatory Visual Methodologies: Social Change, Community and Policy; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4739-4730-6. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, C.; Frisby, W. Continuing the journey: Articulating dimensions of Feminist Participatory Action Research (FPAR). In Sage Handbook of Action Research; Reason, P., Bradbury, H., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-1446271148. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A.; Ping, X.Y. Chinese village women as visual anthropologists: A participatory approach to reaching policymakers. Soc. Sci. Med. 1996, 42, 1391–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleden, H.; Garvin, T.; First Nation, H.; Huu-ay-aht First Nation. Modifying photovoice for community-based participatory indigenous research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.; Smith, F. What’s in focus? A critical discussion of photography, children and young people. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2012, 15, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lisio, A. York University, Toronto, Canada. Personal communication (email), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arora-Jonsson, S. Virtue and vulnerability: Discourses on women, gender and climate change. Global Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciplet, D.; Roberts, J.T. Splintering south: Ecologically unequal exchange theory in a fragmented global climate. In Ecologically Unequal Exchange: Environmental Injustice in Comparative and Historical Perspective; Frey, R.S., Gellert, P.K., Dahms, H.F., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 273–305. ISBN 978-331-989-739-4. [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney, M.J.; Millington, B.; Hayhurst, L.M.C.; Wilson, B.; Ardizzi, M.; Otte, J. “The actual use of them is complex”: Actor-network theory, the bicycle, and other non-human actors in international development. (Under review). Int. Rev. Soc. Sport.

- Slocum, R. Polar bears and energy-efficient lightbulbs: Strategies to bring climate change home. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2004, 22, 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubrium, A.C.; Hill, A.L.; Flicker, S. A situated practice of ethics for participatory visual and digital methods in public health research and practice: A focus on digital storytelling. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 1606–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. Living a Feminist Life. Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0822363194. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hayhurst, L.M.C.; del Socorro Cruz Centeno, L. “We Are Prisoners in Our Own Homes”: Connecting the Environment, Gender-Based Violence and Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights to Sport for Development and Peace in Nicaragua. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4485. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164485

Hayhurst LMC, del Socorro Cruz Centeno L. “We Are Prisoners in Our Own Homes”: Connecting the Environment, Gender-Based Violence and Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights to Sport for Development and Peace in Nicaragua. Sustainability. 2019; 11(16):4485. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164485

Chicago/Turabian StyleHayhurst, Lyndsay M. C., and Lidieth del Socorro Cruz Centeno. 2019. "“We Are Prisoners in Our Own Homes”: Connecting the Environment, Gender-Based Violence and Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights to Sport for Development and Peace in Nicaragua" Sustainability 11, no. 16: 4485. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164485