Abstract

Culinary tourism represents an emerging component of the tourism industry and encompasses all the traditional values associated with the new trends in tourism: respect for culture and tradition, authenticity and sustainability. Italy is known worldwide for the richness and variety of its gastronomy, and agri-tourism represents one of the most important places where culinary tourists can experience local food and beverages. By using a modified version of Kim and Eves’ motivational scale, the present study aims to investigate which motivational factors affect the frequency of culinary tourists to experience local food and beverages in agri-tourism destinations. The findings of the present study reveal that the social and environmental sustainability, among the other motivations, has shown to play a crucial role in influencing Italian tourists’ frequency to experience local food and beverage in agri-tourism destinations.

1. Introduction

The local food movement is part of the contemporary social movements aiming to change the global agricultural landscape by altering the way we understand and interact with the food system [1,2]. Its main goal is focused on shortening the distance between producer and consumer, in order to increase the social, economic and environmental sustainability of the food system, and to strengthen the cultural identity of the territories [3]. According to Feenstra [4], the local food movement is founded on social and cultural interests, by including support for producers, local economies and environmental protection, through the production, processing, distribution and consumption of local foods. An emerging component of this movement is culinary tourism [5], which emphasizes unique foods and dishes from the culture of a specific region [6]. Hall and Sharples [7] considered culinary tourism as the leisure pursuit of a memorable eating and drinking experience, made to places where good foods are prepared for the purpose of fun or entertainment, which incorporates visits to local producers, food fairs, farmers’ markets, cooking demonstrations and any food-related tourism activities. Among EU countries, Italy has shown a considerable growth of culinary tourism over the last years, becoming one of the most dynamic and creative segments of tourism [8]. According to the latest available data [9], culinary tourists in Italy have exceeded 110 million in 2017 (of which 43% domestic tourists), with an economic impact of 12 billion euros (15.1% of the Italian tourism sector). Italy, in fact, represents a tourist destination whose brand image is connected, with varying levels of intensity, to gastronomic values, thanks to the fact that it represents the first EU country for protected designation of origin (PDO), protected geographical indication (PGI) and traditional specialty guaranteed (TSG). According to EU regulations, the PDO label identifies a product in which all the phases of the production process (production, processing and preparation process) must take place in the specific region. The IGP differs from PDO, as at least one of the stages of production, processing, or preparation takes place in the region. TSG refers to all those food products whose production processing is recognized and used throughout the area concerned, according to traditional rules agri-food labels (825 agri-food products with these labels) and traditional agri-food products (5056 labels).

Culinary tourism includes several areas such as wine tourism, beer tourism, gourmet tourism and gastronomic tourism, and tourists can experience it through local and unique restaurants, breweries, wineries, culinary events, farmers’ markets and agri-tourisms [10,11]. In Italy, agri-tourism represents one of the most important places where culinary tourists can experience local food and beverages. As indicated by McGehee and Kim [12], agri-tourism is a farm that combines agricultural production with a component of rural tourism. In Italy, agri-tourisms amounted to 23,406 in 2017, showing an increase of about 27% over the last 10 years [13]. Agri-tourisms are seen as effective means of supporting local economies as they represent an important source of income diversification for farmers [14], and a way to contributing to the preservation of landscapes and cultural heritage in the rural areas [15]. According to the latest available data, in Italy the number of tourists in the agri-tourism sector exceeded 12 million, with an economic impact of over 1.4 billion euros [16]. An estimate, the latter, that seems destined to grow, is also in consideration of the fact that tourists are increasingly interested in consuming food products and dishes that are characteristic of specific territories [17]. Accordingly, the ability of agri-tourisms and territories to attract culinary tourists could assume a winning role for the development of the whole economy in rural areas and to contribute to enhancing the value of the local farm’s products through its association with the social and cultural context [18].

However, to date few efforts have been made to understand culinary tourists’ motivations to experience local foods and beverages [19,20]. With reference to agri-tourism literature, the research has been mainly focused on the supply side of the market, with most studies concerning entrepreneurial motivations [21,22]. Few studies have investigated the tourists’ motivations to visit agri-tourism destinations [23], some of them mainly focused on the recreational component of agri-tourism, including being with family, and enjoying natural landscapes and the smells and sounds of nature [24]. Very few efforts have been done on the link between the tourists’ motivations of experiencing local food and beverage and the interest in visiting agri-tourisms [25]. To the best of our knowledge, no study has explored the role of motivations on the consumption of local food and beverages in agri-tourism destinations in Italy. Furthermore, it is not clear which motivations play a key role in influencing the choice to consume local food in agro-tourism destinations. The current study aims to reduce this gap by contributing to understanding which motivational factors affect the choice of Italian culinary tourists to experience local food and beverages in agri-tourism destinations. Considering the importance of the role played by food in the choice of a tourist destination, findings of the present study could contribute both to enrich the literature on culinary tourism and to drive agri-tourist operators who want to shape their business model to satisfy the costumers’ expectations.

Using a behavioural approach, we conducted a survey in Italy through an online questionnaire with modified items from the Kim and Eves’ scale measurement of tourists’ motivations to consume local food [26]. We chose this scale as it seems the most comprehensive tool for inferring how tourists perceive local food and beverages in agri-tourism destinations. Furthermore, to understand whether motivations linked to sustainability aspects of food consumption affect the choice to experience local food and beverage in agri-tourism destinations, we implemented in Kim and Eves’ scale some motivational items deriving from local food consumption literature.

2. Culinary Tourism and Local Food Consumption: A Focus on the Existing Relevant Literature

Culinary tourism is an increasingly expanding sector of tourism in which tourists experience local food and beverages of other destinations and cultures [27]. Over the years, in fact, culinary tourism is becoming an emergent alternative to mass tourism, inasmuch culinary tourists increasingly try to gain new experiences in an active, differentiated and unique manner than the choice of reaching standardized touristic destinations [28]. What emerges is that many holiday destinations worldwide are very sought-after for their traditional food and beverages [29,30].

In scientific literature, culinary tourists are also called foodies as they, by means of the local food and beverages, are looking for a genuine and memorable experience [31]. Several authors claimed that the most important factor that pushes culinary tourists towards specific destinations is the desire to taste local gastronomy [32,33,34]. Similarly, Dann and Jacobsen [35] highlighted that an important aspect of culinary tourism is to practice variegated sensory experiences, as the taste of local gastronomy is different to the taste of same food in own country or region.

Green and Dougherty [5] conceptualized culinary tourism as a subset of cultural tourism, by asserting that food and beverages are expressions of specific cultures. They perceived local food and beverages as guarantees of authenticity, since they emphasized unique regional dishes, telling a collective memory made of knowledge, flavours and peasant rituals. This was also supported by the UNWTO that recognized food as a key element of all cultures and a major component of global intangible heritage. Culinary tourism, in fact, incorporates moral and economical qualities dependent on the territory, landscape, local culture, local food items and authenticity [36]. In the context of tourism research, motivations are important constructs to understand tourists’ behaviour, as they are seen to affect the choice of a touristic destination [37], or participation to a particular touristic activity [19,38]. In the literature, different motivations have been recognized to affect the choice of tourists to experience local food. Culture seems, in fact, an important motivator that affects culinary tourism. According to Fields [20], tourists’ desire to experience local food and beverages in a tourist destination is strictly linked to cultural motivations, as experiencing new foods and dishes means also experiencing new cultures. In addition, Kim and colleagues [39] showed that healthy eating is another important motivational factor affecting tourists’ interest in local food. They affirmed that tasting local food and beverages in their place of origin is perceived by tourists as a means to improve psycho-physical health, as they are perceived to be fresher and more nutritious.

Culinary tourism is perceived by tourists also as a change of everyday routine and eating habits in order to try new food experiences and to obtain a certain prestige with their family and friends [20,39]. This is in line with Schultz [40] who denoted that nowadays more and more tourists are in search of authentic travel and food experiences, thanks also to the role of the media that have positively influenced tourists’ perspectives about the link between tourism and gastronomy [41].

Moreover, previous studies highlighted as culinary tourism could be an opportunity to socialize and be together with family and other people, as participating in festivals and events based on local food are able to build social relations, by contributing to make the tourist experience more pleasant [42,43]. This is also supported by Sotomayor and colleagues [24], related to agri-tourism experience in Missouri (U.S.), who found that being with family and enjoying natural landscape were important motivators for visiting agri-tourism destinations.

Moreover, Barbieri and colleagues [44] found that experiencing the farm lifestyle and learning about farming are crucial motivations for visiting agricultural environment for recreation. The same is true for the tourists’ perception that agricultural environment is associated with the authenticity of experiences [45,46]. However, little effort has been made to understand how the motivations to visit the agri-tourism destinations are linked to the choice to consume local food and beverages. For example, Kline and colleagues [25] found a positive association between the consumers’ concerns over the humane treatment of animals and environmental impacts of the mainstream supply chain and the interest of tourists to experience local food, in particular, meat, in agri-tourism destinations. The line of research on consumer preference for local food highlights further motivational dimensions affecting consumer choice, including environmental and social sustainability motives [47].

These motivations, which highlight an ethical aspect linked to the consumption of local food, have been little explored in previous research on tourists’ motivation to consume local food [25]. In particular, the literature emphasizes that environmental protection play a crucial role in affecting local food consumption. Indeed, according to Migliore and colleagues [48] consumers are often driven to consume local food because they are motivated to reduce the environmental costs of food production and distribution. Moreover, some studies reported that consumers perceive local food to be better for the environment and also for society than organic food [49].The preference for local food seems linked to the perception that local farms, more in particular, the small-size ones, adopt agricultural practices with less dependence on synthetic pesticides and fertilizers [49].

Several studies highlighted that the growing interest of consumers is often associated with the perception that local food is more nutritious, healthier and of higher quality than that sold in the mainstream supply chain [50,51], also because products have travelled a short distance to reach the consumer’s table [47]. However, the most frequently named motivations for expressed preferences of local food among consumers seem related to environmental protection and support of the local economy [47].

Local food consumption has been recognized to increase social and economic justice in rural communities, as consumers desire to support local farms that have difficulty in entering the traditional commercial channels [52]. In particular, Sage [53] explained that direct interactions between farmers and consumers generate solidarity, promoting the recovery of a sense of morality within the agri-food sector. Indeed, besides supporting farms from an economic point of view, consumers try to create direct relationships based on solidarity and trust.

In scientific literature, several studies have analysed how socio-demographic characteristics of culinary tourists affect their choices and destinations. According to some authors [54,55,56], there is a specific profile of culinary tourists, inasmuch they usually have both a medium-high level of income and education and an age range between 35 and 45 years. In particular, Pérez-Priego et al. [54] showed that the majority of culinary tourists are women, hold a university degree and have a household monthly net income higher than 2000 euro.

By integrating both tourists’ motivation literature and local food research, this study contributes to enriching understanding about motivational factors, and socio-demographic characteristics, influencing the consumption of local food and beverage in Italian agri-tourism destinations.

3. Methodology

3.1. The Modified Kim and Eves’ Scale Measurement of Tourists’ Motivations to Consume Local Food

In the literature on consumer decision-making, motivations refer to a set of psychological constructs that explains why people behave in certain ways. They can be thought of as the antecedent condition that compels human behaviour to occur [19].

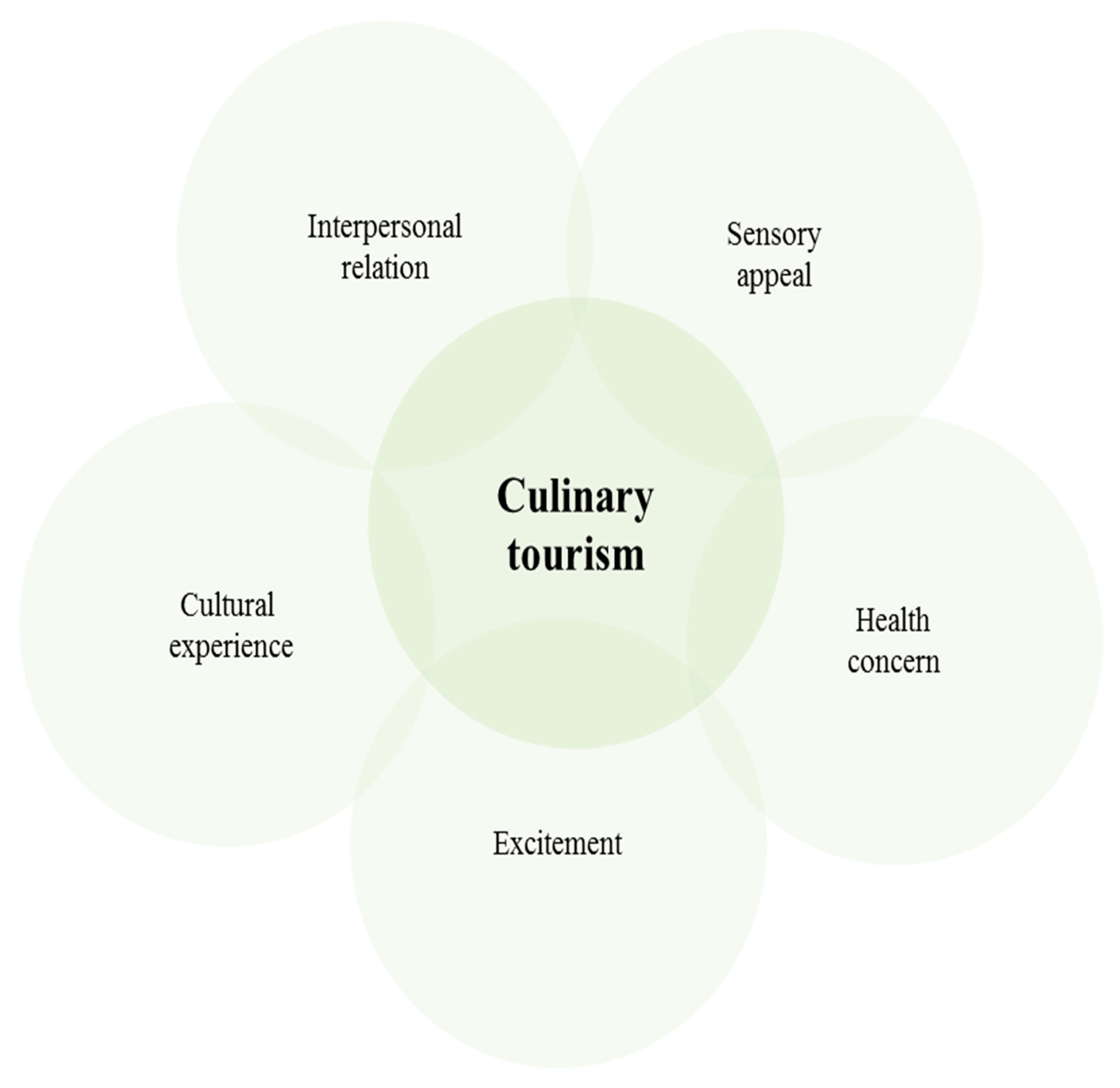

In order to explain tourists‘ behaviour to taste local food and beverages, Kim and Eves [26] developed a motivational scale composed of five motivational dimensions, generated by 26 items. The five motivational dimensions were cultural experience, excitement, interpersonal relation, sensory appeal and health concern (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The five motivational factors of Kim and Eves’ motivational scale.

In particular, ‘cultural experience’ is associated to the tourists’ desire to experience different cultures, since experiencing new foods and dishes means also experiencing new cultures. ‘Excitement’ dimension is related to the need to practise exciting experiences during holiday, also associated with the need to escape from routine.

The third dimension identified by Kim and Eves was ‘interpersonal relation’, which is seen as a desire to meet new people, spend time with friends and family and get away from routine relationship.

Culinary tourism is also seen as a sensory experience. ‘Sensory appeal’ is, in fact, the fourth dimension found by Kim and Eves and it is related to the sensory characteristics of food that can play an important role in culinary tourist’ choices. ‘Health concerns’ is the fifth motivational dimension affecting local food and beverages consumption in touristic destinations identified by Kim and Eves.

Moreover, several previous studies have highlighted that prestige is another factor affecting tourist choice to experience local food and beverage in tourist destinations. In fact, Kim and colleagues [39], Crompton and McKay [19] and Botha and colleagues [57] pointed out that prestige, in the context of local food experience, is an expression of self-esteem and it derives from the need to create a favourable impression on other people. Therefore, considering the above-mentioned motivational factors, a modified version of Kim and Eves’ motivational scale was proposed in this study, including new items deriving from local food literature. More in detail, in Table 1, are reported the 26 original items from Kim an Eves’ scale, 4 items from previous studies on tourists’ prestige, and 10 items recognized on local food literature, emphasizing the social and environmental sustainability, as well as the healthy eating associated with local food.

Table 1.

Modified version of Kim and Eves’ (2012) motivational scale.

3.2. Data Collection and Methods

In order to detect and measure the effects of tourists’ motivations on the frequency of consumption on local food and beverages in agri-tourisms, an online survey was performed, involving 412 Italian tourists who visited agri-tourism destinations. Data were collected between the spring and winter 2018, and participants were recruited through invitations to participate in the online survey. In this study, a snowball sampling recruitment technique was adopted, as it allowed to reach a large number of participants by means of their interpersonal relations and their social connections. It is worth noting that, despite this technique did not provide a fully representative sample, it allowed collecting a wide variety of information in a short time [58,59]. For the survey, a questionnaire was adopted, which was organized in three sections. In the first section, information was collected regarding the frequency of local food consumption in agri-tourism destinations, the main occasions affecting this frequency (e.g., food festivals, cooking school, or just to experiencing local food in its area of origin), and the preferred place for agri-tourism destination (rural area far from the cities or near tourist attractions). The second section of the questionnaire was reserved to gather information about the main motivations affecting tourist to taste local food and beverages in agri-tourism destinations. For each motivational items, participants were asked to rate the level of importance for these motivational items using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7 (where 1 was not important and 7 was very important). The third section of the questionnaire included participants’ socio-demographic indicators, such as age, gender, education (in four categories: primary school, lower secondary school, upper secondary school and a university degree or higher) and household monthly net income measured in euros.

Of the 412 questionnaires collected, 29 were deleted because they were incomplete, while 383 were retained for the analysis. To identify the main motivational factors of Italian agri-tourists, data were analysed using a Principal Component Analysis (PCA). It allowed the analytical transformation of a set of correlated variables into a smaller number of independent variables or constructs, reducing the number of variables while minimizing the loss of information. To achieve a more meaningful and interpretable solution, during the extraction process, items with factor loadings higher than 0.5 were retained, while those with a value lower that 0.5 and those cross-loaded on more than one factor were eliminated (more in particular, they are the items No. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 19, 22, and 23, shown in Table 1). Cronbach’s alpha was also calculated to measure the internal consistency of items in each factor or principal component. After that, factor scores were also calculated for each principal component, expressing the contribution of each observation to the composition of factors. The factor scores were used for the subsequent ordered logit econometric model, allowing ordered categories of a dependent variable to be modelled as a sequence of latent variables, y*, through increasing threshold levels [60].

The dependent variable was constructed as the annual frequency of local food and beverages consumption in agri-tourism destinations. This was subdivided into three categories in increasing size by level of consumption: ‘low’, frequency of local food consumption in agri-tourism destinations less than 2 times a year; ‘medium’, frequency of local food consumption between 2 and 4 times a year; and ‘high’, frequency of local food consumption in agri-tourism destination higher than 4 times a year (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of the three categories of the dependent variable.

The independent variables were the factor scores obtained from PCA and some other agri-tourists’ socio-demographic characteristics. In order to measure the effects of each motivational factor on local food and beverages consumption, the odds ratios (ORs) were also determined. An OR quantifies the changes in the probability of the dependent variable after a unit change in the independent variable. This means that when the OR is equal to 1, the effect of the unit variation of the independent variable on the dependent variable is null, thereby maintaining the values of the other explanatory variables constant; the larger the deviation from the unit value, the greater the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable [60].

4. Results

Of 383 participants in the survey, 209 were females (equal to about 55% of the respondents). Data processing showed that the average age of agri-tourists participating in the survey was 34 years ranging from 25 to 72 years, and 46% had a university degree and almost 50% had an upper secondary school. Over 53% of them lived in a household of three or four members. In total, 45% of respondents declared a household monthly net income between 2160 euros and 3240 euros, 18.5% of them between 3241 euros and 4350 euros, while only 6.3% declared a household monthly net income of over 5400 euros. Moreover, 31% of respondents visit agri-tourism destinations during food festivals, 42% just to experience local food in its area of origin and about 27% for cooking schools or other events organized in agri-tourism. The application of factor analysis allowed reducing the initial number of variables (31) into 6 factors, which accounted for 63.4% of the total variance. The KMO value at 0.93 exceeded the acceptable minimum value of 0.6 [61], and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was observed to be significant (p < 0.000). The Cronbach’s alpha scores were higher than 0.7, ranging from 0.78 to 0.89, indicating that the variables exhibited correlation with their factors and can be considered as internally consistent [61].

The Factor Analysis allowed identifying the main motivational factors characterizing tourists’ choice to consume local food in agri-tourism destinations (Table 3). The first factor extracted, which represented one of the motivational dimensions characterizing tourists’ choice, accounted for 16.8% of the explained variance and was named ‘social and environmental sustainability’. It is characterized by items associated with the motivations of being in solidarity with local farmers, of contributing to the local economy, of maintaining the agricultural landscape, of eating food that has not travelled for long distance, of conserving the local environment and its natural resources, of perceiving local food more environmentally-friendly, and with the motivation associated with the importance that local food ate in agri-tourism is organically certified.

Table 3.

Explorative factor analysis results.

The second motivational factor extracted was named ‘health concern’ and what’s more, it represented 13.8% of the explained variance. This factor is characterized by the items emphasizing the health aspects of local food, that is, local food is good for health, it is more nutritious, it is perceived free of synthetic chemicals harmful to health, it contains a lot of fresh ingredients produced in the local area and knowing the producer is guarantee of the wholesomeness of local food. The third motivational factor extracted accounted for 11.8% of the explained variance. It was named ‘cultural experience’ as it is characterized by items associated with the opportunity that eating local food increases the knowledge about different local cultures and increases understanding about local cultures, and with the perception that experiencing local food is an authentic experience and creates excitement. Compared to Kim and Eves’ scale [26], in this study the excitement dimension has been incorporated into the cultural experience dimension, almost to emphasize that cultural motivations are associated with the desire to have an exciting experience.

The fourth motivational factor was named ‘prestige’, as a holiday destination, such as agri-tourism, through its local food and beverage can communicate something about tourists’ status. This factor accounted for 10.9% of the explained variance and is characterized by items associated to the desire to take a picture of local food to show friends, to give advice about local food experiences to people who want to travel, to talk about local food experience and to enrich intellectually.

The fifth motivational factor accounted for 5.4% of the explained variance and was explained by two variables. It was named ‘sensory appeal’, as it is characterized by the importance that the local food ate in agri-tourism tastes good and smells nice. The sixth motivational factor was called ‘interpersonal relation’. It is characterized only by two items that emphasize the role of local food associated to the desire to spend time with friends and family and a means to meet new people with similar interest.

As mentioned in the methodology section, the factors score of motivations identified during factor analysis process were analysed, together to the socio-demographic variables of respondents, with an ordered logistic econometric model. The explanatory variables implemented in the model approximate the main motivational factors and socio-demographic characteristics, affecting the choice of Italian culinary tourists to consume local food and beverages in agri-tourism destinations. Coefficients with a positive sign indicating that as an explanatory variable increase, so do the probability of falling in the category with the highest frequency of local food consumption in agri-tourist destinations. Some of the signs of the estimated coefficients were highly significant and consistent with the expected signs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of the econometric model (Ordered Logistic Regression).

The latent variable, defined as the frequency of local food consumption in agri-tourist destinations, increased with the rise in all the explanatory variables apart from ‘health concern’ and ‘sensory appeal’ motivational factors which were statistically not significant in explaining the high frequency of local food consumption in agri-tourist destinations. However, it is important to note that the non-significance of these two motivational factors could be due to the high mean values that the respondents gave to the related items, regardless of the agri-tourists’ local food consumption levels.

The results obtained described the influence of the motivational factors on tourists’ choice to experience local food and beverages at agri-tourist destinations. In particular, the frequency of local food consumption among participants increases with the growing importance attributed to particular factors. It was found that four of the six motivational factors examined (cultural experience, prestige, social and environmental sustainability, and interpersonal relation) were important in influencing tourists’ local food consumption.

Among the socio-demographic variables, ‘age’ ‘gender’ and ‘income’ were found to increase the probability of consuming local food in agri-tourist destinations. The negative sign of coefficient related to the variable ‘gender’ showed that being female increases the probability to experience local food and beverages in agri-tourist destinations. Among the socio-demographic variables, only ‘education’ was not statistically significant. The not-statistically-significant nature of this variable could be due to the high level of education of participants; in fact, as previously mentioned almost 96% had a upper secondary school and a university degree.

The calculation of the odds ratios (ORs) revealed the ratio between the probability of high frequency of local food consumption in agri-tourist destinations and the cultural experiences, prestige, social and environmental sustainability, and togetherness motivational factors. Meanwhile, among the factors identified in the factor analysis, the ‘social and environmental sustainability’ motivational factor showed the biggest influence on the probability to have a high frequency of local food consumption in agri-tourism destinations (1.44 times); followed in order by the ‘cultural experience’ motivational factor (about 1.39 times), ‘prestige’ and ‘interpersonal relation’ motivational factors, which showed almost the same effect (about 1.32 and 1.30 times, respectively). Among the socio-demographic variables, only income showed a relatively biggest influence on the probability to have a high frequency of local food consumption in agri-tourism destinations (1.10 times).

5. Discussion

By integrating existing studies investigating motivations to consume local food and the stream of research on tourists’ motivations, the present study set out to investigate the main motivational factors affecting the choice of culinary tourists to taste local food and beverages in Italian agri-tourism destinations. Gastronomy, in fact, is one of the most important elements affecting the authenticity of a tourist destination. Italy is known worldwide for the richness and variety of its gastronomy [17], and agri-tourism represents one of the most important places where culinary tourists can experience local food and beverages [62]. This is one of the first study investigating tourists’ motivation to experience local food and beverage in agri-tourism destinations, revealing that ‘cultural experience’, ‘prestige’, ‘interpersonal relation’ and ‘social and environmental sustainability’ play a crucial role in influencing Italian tourists’ frequency to consume local food and beverage in agri-tourism destinations. Relative to ‘cultural’ motivator, Kim and colleagues [39] highlighted that local food is an important means through which tourists experience the culture of a destination. Similarly, Fields [20] suggested that cultural motivation allows tourists to experience the culture of a particular destination, making them closer to the place. Also, Kim and Eves [26] found that culture is an important aspect of local food consumption since experiencing local food allows tourists to increase knowledge about different local cultures. This is also consistent with Ruiz Guerra and colleagues [46], who emphasized that culinary tourism, in particular oleotourism, seeks to combine environment, culture, tradition and gastronomy that create a new model of sustainability in rural environments. ‘Prestige’ is another important motivator influencing the consumption of local food and beverage in agri-tourism destinations. This is reliable with past research, uncovering that local food experience has a role in conscience improvement or smugness [39]. McIntosh et al. [38] described status and prestige motivations as closely related to the tourists’ wish of attracting attention from others. This was also discussed by Hall and Winchester [63] who observed that the tourists’ desire to learn about traditional food or wine contributes to creating a favourable impression on others. ‘Interpersonal relation’ is also recognized to play a crucial role in tourists’ behaviour to have a high frequency of consumption in agri-tourism destinations. This is also consistent with Kim and Eves [26] who pointed out that socializing with new people and being together with family is recognized to be an important factor in tourist motivation to experience local food and beverage in tourist destinations. Social and environmental sustainability is a new motivational factor that the econometric analysis showed to play an important role in explaining tourists’ behaviour to consume high frequency of local food in agri-tourism destinations. This is in line with Kline and colleagues [25] who found that animal welfare and environmental sustainability are important motivators for eating local meat in agri-tourism destinations. This is also supported by the literature on local food consumption, revealing that the desire to protect the environment play a crucial role in consumers interest towards local food [64,65]. Migliore and colleagues [47] highlighted that consumers’ concerns to reduce the environmental costs of food production and distribution plays a crucial role in influencing consumers’ interest in local food. Seyfang [66] emphasized that the ‘re-localization’ of food is associated to consumers’ motivation of reducing the impacts of ‘food miles’, understood as the distance food travels between being produced and being consumed. The environmental and social sustainability dimension is also linked to the importance tourists attribute to the organic certification of local food products. This is consistent with Basha and Lal [67] who highlighted that environmental concern and the desire to help local producers assisted the economy, developed their society and significantly affected the purchasing intentions for organically produced foods.

However, compared to Kline and colleagues [25], the present study highlights that social sustainability is another important motivation that together with environmental sustainability plays a crucial role in affecting the choice to consume local food in agri-tourism destinations. This is consistent with Zepeda and Leviten-Reid [68] who emphasised that consumers are motivated to purchase local food, as they wish to sustain the social and economic conditions of a local rural community, by recirculating financial capital and encouraging new forms of entrepreneurship. This contributes to the resilience of rural communities, where local farms are often strongly integrated, playing a positive role in strengthening and supporting the social and economic conditions of the local community [69,70]. This is particularly true in a rural tourism context since tourism could represent one of the most important economic development strategies in these areas [71]. Ferrari et al. [72], in fact, showed that an increase in rural tourists results in an overall positive increase in demand both for local food productions and handicraft products, generating an increase in regional value-add. This result strongly supports the relevance of sustainability as a crucial determinant of the competitiveness of agri-tourism destinations. Research seems to agree that the competitive destination has to deliver an experience that is more satisfying compared to similar destinations, and it is associated with the ability to preserve natural and cultural resources, which, in turn, increases long-term well-being of its residents [17,73,74]. This has important implications for rural development, as at farm level, tourism contributes to enhancing the value of the farm’s products through its association with the social and cultural context [18]. Thus, culinary tourism plays a crucial role in the sustainable development of territories, as it allows to improve its economy and also to strengthen the cultural and social identity of residents [75]. The strong linkage between local food and tourism could stimulate the creation of entrepreneurial networks in a territory, by strengthening the whole economy and increasing the quality of life of residents [76]. In this context, the culinary tourism can represent a way to reduce the growing problem of sustainability in tourism, by ensuring socio-economic development of entire communities [77]. Therefore, agri-tourism destinations could represent an alternative to the unsustainable mass tourism practices, which have caused a detrimental use of urban and coastal spaces for tourism purposes [78].

However, in the analysis, not all these motivational factors identified during the factor analysis procedure are able to explain the high frequency of consumption of local food in agri-tourism destinations. Although ‘health concern’, as shown in the econometric results, is not a motivator influencing the frequency of consumption of local food in agri-tourism destinations, it was found to be an important characteristic of local food in holiday destinations, regardless of how often local food is consumed. The same is true for ‘sensory appeal’ motivational factors. The high scores on the items related to the perception that local food is healthy are rather in line with the previous literature, where local food is perceived to be fresher and more nutritious than the food that has travelled for long distances [51] and free of synthetic chemicals [47]. Moreover, knowing the producer is perceived by consumers as a guarantee of the wholesomeness of local food [48].

Finally, relative to socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, similar to Baderas-Cejudo et al. [79] and Nicoletti et al. [80], findings reveal that being older and with a higher level of household monthly net income significantly increase the probability of tourists to experience local food and beverages. In particular, older tourists seem to feed an important niche market, as they have both the time and purchasing power to try and experience local food and beverages, especially in rural areas. On the contrary, other studies showed that culinary tourists usually are aged between 35 and 45 years, and women are more attracted towards gastronomy destinations than men [81,82].

Although the results of the present study show that the variable educational level is not statistically significant to explain the frequency of local food consumption at agri-tourism destinations, the educational levels of participants is rather high as emphasized in other studies [83,84].

6. Conclusions, Limitations, Implications and Future Research

In an era of globalisation, there is a particular desire to enjoy varied, rather than mono-cultural ambience and experience. In this context, over the last years, in order to increase the social, economic and environmental sustainability of the food system, and to strengthen the cultural identity of the territories, local food movements are spreading worldwide. Culinary tourism represents an emerging component of the tourism industry and encompasses all the traditional values associated with the new trends: respect for culture and tradition, a healthy lifestyle, authenticity, and sustainability. Accordingly, promoting culinary tourism in agri-tourisms represents a winning strategy for the development of the whole economy of rural areas.

At the local level, in fact, food and beverages experienced in agri-tourism can contribute to rural socio-economic development by creating new job opportunities and new added value, becoming a resource especially for many small-sized farms that cannot compete in an increasingly globalized market. Similarly, rural areas can play a crucial role in differentiating the tourism offer, giving the opportunity to experience local cultures and traditional dishes and beverages.

The results seemed to show that different motivations affect tourist in agri-tourism destinations; however, the main motivational factor that seems to explain the consumption of local food and beverages in agri-tourism destinations is ‘social and environmental sustainability’, a new motivational factor deriving from the measurement-scale proposed. This highlights that sustainability could play a crucial role in the competitiveness of agri-tourism destinations.

Understanding which motivational factors affect the tourists’ choice to consume local food and beverages in agri-tourism could contribute to defining competitive marketing strategies of tourist destinations, in order to better align them to tourists’ preferences. Marketing is a useful tool for agri-tourism’s competitive strategy, as it provides agri-tourism operators with the ability to differentiate the products or experiences they offer from those of their competitors. For example, agri-tourism operators could focus their strategies by communicating the link between culinary tourism and the environmental and social sustainability of agri-tourism destinations. Therefore, it could be important for agri-tourisms to adopt CSR initiatives and business strategies focused on the social and environmental components of sustainability. In line with this, the adoption of certified environmental management systems, such as organic certification for local foods, could contribute to satisfying the needs of tourists in the environmental field. From this point of view, it is essential for the agri-tourisms adopting effective communication strategies, for example, the CSR reporting, in order to communicate to the tourists and local communities the engagement in the environmental and social field. At the same time, agri-tourism operators should commit themselves to better communicate the link between the local food and territories and the cultural content of dishes offered.

The findings of the present study could also enrich the extant literature on culinary tourism and agri-tourism demand, and reinforce business literature which supports that consumers have a positive attitude towards sustainable food products and tourism.

However, the present study faces some limitations. They are inherent to its very methodological nature and to the convenient sample used in the study, based on the voluntary participation of respondents. Therefore, the study does not intend to provide conclusive evidence but helps readers to have a better understanding of the trend of culinary tourism in agri-tourism destinations. Moreover, this study only focused on motivations, which are a part of psychological factors known to influence behaviour. Excluded were other individual factors such as attitudes, consumers’ awareness and personal values, as well as cultural and social factors.

Therefore, further advancement in culinary tourism research should take into account a larger sample, as well as extending the study to foreign tourists’ preferences, and other social and cultural contexts in order to validate the effort proposed in this study. Finally, future research should incorporate different theories to better understand the complex issue of individual behaviour. Furthermore, in the light of the increase in the agri-tourism demand, further research should take into account the Dialogical Self Theory or the Social Capital Theory [85] in order to explain how local communities shape their perceptions in light of changes in the environment due to a growing tourists’ presence in the rural area.

Author Contributions

This study is a result of the full collaboration of all the authors. However, R.T. conceived and designed the study, wrote the ‘Culinary Tourism and Local Food Consumption: A focus on the Existing Relevant Literature’ section, and ‘The Modified Kim and Eves’ Scale Measurement of Tourists’ Motivations to Consume Local Food’ sub-section, G.S. and A.M.D.T. collaborated to write the ‘Data Collection and Methods’ sub-section and ‘Conclusions’ section, and A.G. wrote the ‘Discussion’ section, while G.M. wrote ‘Introduction and Results’ sections, and coordinated the study.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Migliore, G.; Romeo, P.; Testa, R.; Schifani, G. Beyond Alternative Food Networks: Understanding Motivations to Participate in Orti Urbani in Palermo. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forno, F.; Graziano, P.R. Sustainable community movement organisations. J. Consum. Cult. 2014, 14, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, G.; Forno, F.; Dara Guccione, G.; Schifani, G. Food Community Networks as sustainable self-organized collective action: A case study of a solidarity purchasing group. New Medit 2014, 13, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Feenstra, G. Creating space for sustainable food systems: Lessons from the field. Agric. Hum. Values 2002, 19, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, G.P.; Dougherty, M.L. Localizing linkages for food and tourism: Culinary tourism as a community development strategy. Community Dev. J. 2008, 39, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.M. Culinary Tourism: Food, Eating and Otherness; University of Kentucky Press: Lexington, KY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L. The consumption of experiences or the experience of consumption? An introduction to the tourism of taste. In Food Tourism around the World; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Mitchell, R., Macionis, N., Cambourne, B., Eds.; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, S.; Gilli, M. Authenticity and experience in sustainable food tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Sustainable Food, Beverage and Gastronomy; Sloan, P., Legrand, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 315–325. [Google Scholar]

- ISNART, 2018. Turismo ed Enogastronomia. Available online: http://www.isnart.it/bancadati/downloadDocumenti.php?idDoc=439 (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Wolf, E. Have Fork Will Travel: A Practical Handbook for Food & Drink Tourism Professionals; World Food Travel Association: Portland, OR, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koc, E. The new agritourism: Hosting community & tourists on your farm. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 1085–1086. [Google Scholar]

- McGehee, N.G.; Kim, K. Motivation for agri-tourism entrepreneurship. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT, 2018. Report: Le Aziende Agrituristiche in Italia. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/221471 (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Santucci, F.M. Agritourism for Rural Development in Italy, Evolution, Situation and Perspectives. In Proceedings of the VII International Academic Congress “Fundamental and Applied Studies in EU and CIS Countries”, Cambridge, UK, 26–28 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti, A.K.; Beccaro, G.L.; Bruun, S.; Donno, D.; Bonvegna, L.; Bounous, G. Assessment methods for sustainable tourism declarations: The case of holiday farms. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrietour, 2018. Agriturismo: Settore da 1,4 Miliardi di Euro Oltre All’indotto Generato. Available online: http://www.agrietour.it/comunicati (accessed on 4 April 2019).

- Cucculelli, M.; Goffi, G. Does sustainability enhance tourism destination competitiveness? Evidence from Italian Destinations of Excellence. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contini, C.; Scarpellini, P.; Polidori, R. Agri-tourism and rural development: The Low-Valdelsa case, Italy. Tour. Rev. 2009, 64, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L.; McKay, S.L. Motives of visitors attending festival events. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, K. Demand for the gastronomy tourism product: Motivational factors. In Tourism and Gastronomy; Hjalager, A., Richards, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tew, C.; Barbieri, C. The perceived benefits of agritourism: The provider’s perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C. An importance-performance analysis of the motivations behind agritourism and other farm enterprise developments in Canada. J. Rural Community Dev. 2010, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Santeramo, F.G.; Barbieri, C. On the demand for agritourism: A cursory review of methodologies and practice. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2017, 14, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotomayor, S.; Barbieri, C.; Stanis, S.W.; Aguilar, F.X.; Smith, J.W. Motivations for recreating on farmlands, private forests, and state or national parks. Environ. Manag. 2014, 54, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, C.; Barbieri, C.; LaPan, C. The influence of agritourism on niche meats loyalty and purchasing. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Eves, A. Construction and validation of a scale to measure tourist motivation to consume local food. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1458–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.M. Culinary Tourism; University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli, M. Niche Tourism: Contemporary Issues, Trends and Cases; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, R.N.; Getz, D. Getting involved: ‘Foodies’ and food tourism. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference “CAUTHE 2012: The New Golden Age of Tourism and Hospitality”; Book 2; La Trobe University: Melbourne, Australia, 2012; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Hjalager, A.M. Repairing innovation defectiveness in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, S.; Ryan, C. Analyzing the evolution of Singapore’s world gourmet summit: An example of gastronomic tourism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Yeoman, I. What is food tourism? Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R. Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Avieli, N. Food in tourism: Attraction and impediment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 755–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.M.; Jacobsen, J.K. Leading the tourist by the nose. In The Tourist as a Metaphor of the Social World; Dann, G.M.S., Ed.; CABI Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 209–236. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Global Report on Food Tourism; The United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2012; Available online: http://cf.cdn.unwto.org/sites/all/files/pdf/food_tourism_ok.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2019).

- Prentice, R. Tourist motivation and typologies. In A Companion to Tourism; Lew, A.A., Hall, C.M., Williams, A.M., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 261–279. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, R.W.; Goeldner, C.R.; Ritchie, J.B. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies, 7th ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Eves, A.; Scarles, C. Building a model of local food consumption on trips and holidays: A grounded theory approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J. The Future of Food Tourism: Foodies, Experiences, Exclusivity, Visions and Political Capital; Yeoman, I., Meethan, K., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2015; Volume 71. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, B. Gastronomy tourism and the media. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, D.C.; Bruun, T.J. The role of socio-psychological and culture education motives in marketing international sport tourism: A cross-cultural perspective. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, J.A.; Zhang, P.; Di Pietro, R.B.; Meng, F. Food tourist segmentation: Attitude, behavioral intentions and travel planning behavior base on food involvement and motivation. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2017, 20, 129–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Xu, S.; Gil-Arroyo, C.; Rich, S.R. Agritourism, farm visit, or...? A branding assessment for recreation on farms. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 1094–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazariadli, S.; Morais, D.B.; Barbieri, C.; Smith, J.W. Does perception of authenticity attract visitors to agricultural settings? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Guerra, I.; Molina, V.; Quesada, J.M. Multidimensional research about oleotourism attraction from the demand point of view. J. Tour. Anal. Revista de Análisis Turístico 2018, 25, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, S.; Migliore, G.; Schifani, G.; Schimmenti, E.; Padel, S. Motives for buying local, organic food through English box schemes. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1600–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, G.; Di Gesaro, M.; Borsellino, V.; Asciuto, A.; Schimmenti, E. Understanding Consumer Demand for Sustainable Beef Production in Rural Communities. Qual.-Access Success 2015, 16, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- La Trobe, H. Famers’ market: Consuming local rural produce. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2001, 25, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, C.; Hamm, U. How important is local food to organic-minded consumers? Appetite 2016, 96, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, A.; Migliore, G.; Verneau, F.; Schifani, G.; Cembalo, L. Are “good guys” more likely to participate in local agriculture? Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 45, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranfield, J.; Henson, S.; Blandon, J. The Effect of Attitudinal and Sociodemographic Factors on the Likelihood of Buying Locally Produced Food. Agribusiness 2012, 28, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, C. Social embeddedness and relations of regard: Alternative ‘good food’ networks in south-west Ireland. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Priego, M.A.; García-Moreno García, M.B.; Gomez-Casero, G.; Caridad y López del Río, L. Segmentation Based on the Gastronomic Motivations of Tourists: The Case of the Costa Del Sol (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Okumus, F.; Okumus, B. Food tourism as a viable market segment: It’s all how you cook the numbers! J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamied, H.H.S. Customers’ perceptions of floating restaurants in Egypt. Anatolia–Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, C.; Crompton, J.L.; Kim, S. Developing a revised competitive position for Sun/Lost City, South Africa. J. Travel Res. 1999, 37, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Schifani, G.; Crescimanno, M.; Migliore, G. “Natural wine” consumers and interest in label information: An analysis of willingness to pay in a new Italian wine market segment. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 227, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, D. Web-based market research: The dawning of a new age. Direct Mark. 1998, 61, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, P.K. Microeconometrics: Methods and Applications; Cameron, A.C., Trivedi, P.K., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- De Lillo, A.; Argentin, G.; Lucchini, M.; Sarti, S.; Terraneo, M. Analisi Multivariata per le Scienze Sociali; Pearson Paravia Bruno Mondadori: Piacenza, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dragulanescu, I.V.; Lanfranchi, M.; Giannetto, C. Agritourism farm in rural development framework and environmental sustainability. Qual.-Access Success 2016, 17, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.; Winchester, M. Empirical analysis of Spawton’s (1991) segmentation of the Australian wine market. Asia Pac. Adv. Consum. Res. 2001, 4, 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, M.; Di Vita, G.; Bracco, S. Direct sale of agro-food product: The case of wine in Italy. Qual.-Access Success 2014, 15, 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vita, G.; D’Amico, M.; La Via, G.; Caniglia, E. Quality perception of PDO extra-virgin olive oil: Which attributes most influence Italian consumers? Agric. Econ. Rev. 2013, 14, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Seyfang, G. Ecological citizenship and sustainable consumption: Examining local organic food networks. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, M.B.; Lal, D. Indian consumers’ attitudes towards purchasing organically produced foods: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Leviten-Reid, C. Consumers’ views on local food. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2004, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Obach, B.; Tobin, K. Civic agriculture and community engagement. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 31, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittman, H.; Beckie, M.; Hergesheimer, C. Linking local food systems and the social economy? Future roles for farmers’ markets in Alberta and British Columbia. Rural Sociol. 2012, 77, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanian, M.; Ghoochani, O.M.; Crotts, J.C. An application of European Performance Satisfaction Index towards rural tourism: The case of western Iran. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 11, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, G.; Mondéjar Jiménez, J.; Secondi, L. Tourists’ Expenditure in Tuscany and its impact on the regional economic system. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Sakka, G.; Crescimanno, M.; Tulone, A.; Fiore, M. What is the role of social media in several overtones of CSR communication? The case of the wine industry in the Southern Italian regions. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 856–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffi, G.; Cucculelli, M.; Masiero, L. Fostering tourism destination competitiveness in developing countries: The role of sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.D.; Mossberg, L.; Therkelsen, A. Food and tourism synergies: Perspectives on consumption, production and destination development. Scand. J. Hospit. Tour. 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.M.; Richards, G. Tourism and Gastronomy, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Martinez, U.J.; Sanchís-Pedregosa, C.; Leal-Rodríguez, A.L. Is Gastronomy a relevant factor for sustainable tourism? An empirical analysis of Spain Country Brand. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Cheer, J.M. Overtourism and tourismphobia: A journey through four decades of tourism development, planning and local concerns. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 353–357. [Google Scholar]

- Baderas-Cejudo, A.; Patterson, I.; Leeson, G.W. Senior Foodies: A developing niche market in gastronomic tourism. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2019, 16, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, S.; Medina-Viruel, M.J.; Di-Clemente, E.; Fruet-Cardozo, J.V. Motivations of the Culinary Tourist in the City of Trapani, Italy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Kozak, M.; Ferradeira, J. From tourist motivations to tourist satisfaction. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 7, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Andersson, T.; Vujicic, S.; Robinson, R.N.S. Food events in lifestyle and travel. Event Manag. 2015, 19, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Beltrán, J.; López-Guzmán, T.; González Santa-Cruz, F. Gastronomy and tourism: Profile and motivation of international tourism in the city of Córdoba, Spain. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2016, 14, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. Local food: A source for destination attraction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Martín, J.; Guaita Martínez, J.; Salinas Fernández, J. An analysis of the factors behind the citizen’s attitude of rejection towards tourism in a context of overtourism and economic dependence on this activity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).