Modified Pyramid of CSR for Corporate Image and Customer Loyalty: Focusing on the Moderating Role of the CSR Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

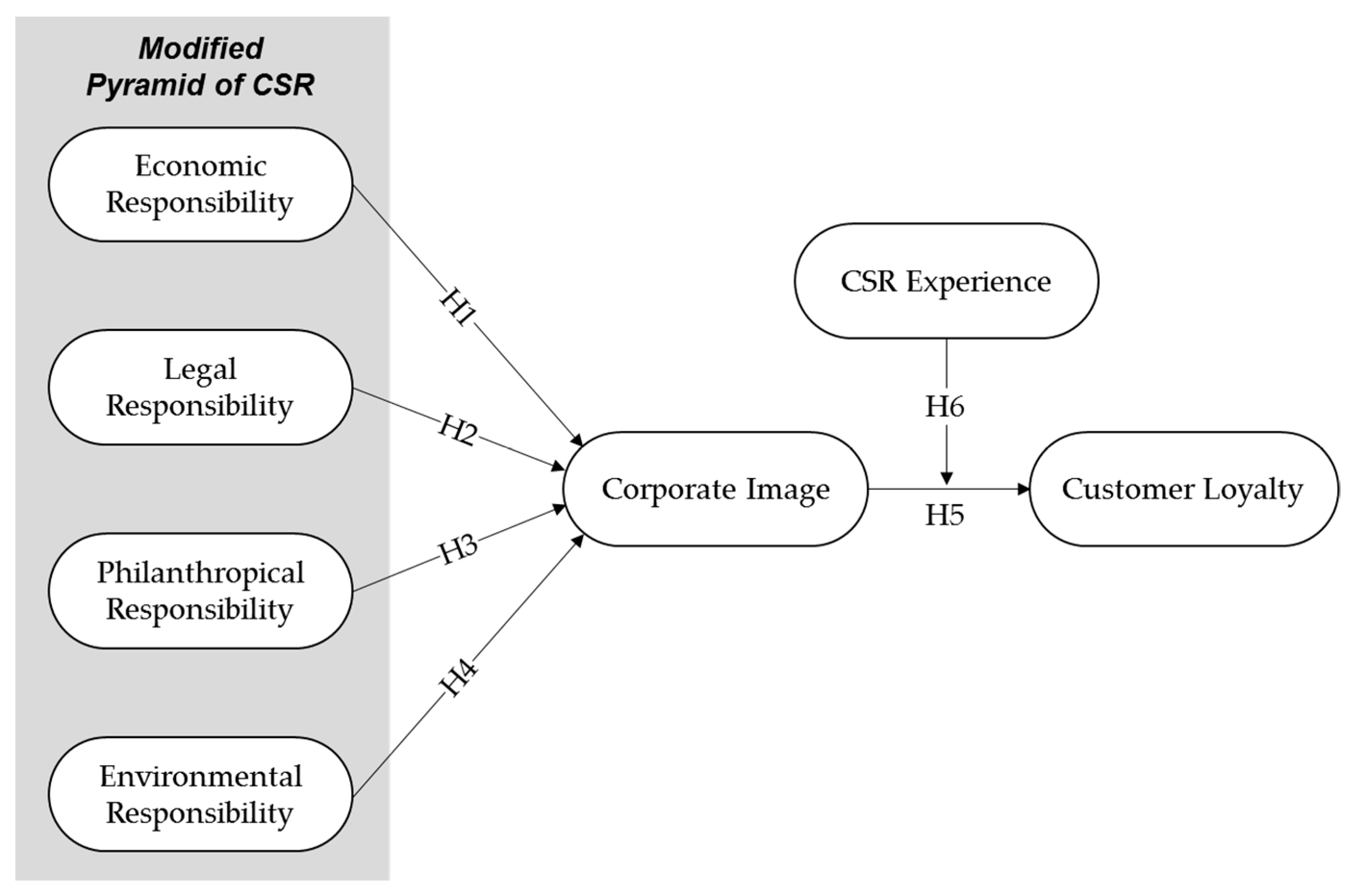

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Definition of CSR

2.2. CSR in Airline Industry

2.3. How CSR Affect Corporate Image

2.4. Corporate Image and Customer Loyalty

2.5. Moderator: CSR Experience

3. Methodology

3.1. Samples

3.2. Variables

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Reliability and Factor Analysis

4.3. OLS Regression

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Summary

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frey, N.; George, R. Responsible tourism management: The missing link between business owners’ attitudes and behaviour in the Cape Town tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, M.; Charlton, C.; Munt, I. Tourism and Responsibility: Perspectives from Latin America and the Caribbean; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, R.J. Managing corporate sustainability and csr: A conceptual framework combining values, strategies and instruments contributing to sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E. Corporate social responsibility as a determinant of corporate reputation in the airline industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.B.; Ramus, C.A. Calibrating MBA job preferences for the 21st century. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2003, 10, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, W. Environmental corporate social responsibility and the strategy to boost the airline’s image and customer loyalty intentions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, T.; Fenclova, E.; Dinan, C.; Coles, T. Tourism and corporate social responsibility: A critical review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, E.D. Corporate social responsibility in aviation. J. Air Transp. 2006, 11, 66–87. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, W.H.; Hsu, J.L. Corporate social responsibility programs choice and costs assessment in the airline industry—A hybrid model. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2008, 14, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, B.L.M.; Chan, W.W. A study of environmental reporting: International Japanese airlines. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 12, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.C.; Kremer, G.E.O.; Phuong, N.T.; Hsu, C.W. Motivations and barriers for corporate social responsibility reporting: Evidence from the airline industry. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2016, 57, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lyu, S.O. Understanding first-class passengers’ luxury value perceptions in the US airline industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilkhanizadeh, S.; Karatepe, O.M. An examination of the consequences of corporate social responsibility in the airline industry: Work engagement, career satisfaction, and voice behavior. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2017, 59, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J.; Song, H.J.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, S.K. The impact of CSR on airline passengers’ corporate image, customer trust, and behavioral intentions: An empirical analysis of safety activity. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 26, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Informa UK Limited: Colchester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergami, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. Self-categorization, affective commitment and group self-esteem as distinct aspects of social identity in the organization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 39, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinel, E.C.; Long, A.E.; Landau, M.J.; Alexander, K.; Pyszczynski, T. Seeing I to I: A pathway to interpersonal connectedness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Song, H.J.; Lee, H.M.; Lee, S.; Bernhard, B.J. The impact of CSR on casino employees’ organizational trust, job satisfaction, and customer orientation: An empirical examination of responsible gambling strategies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A company-level measurement approach for CSR. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; McVea, J. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management. In The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management; Hitt, M.A., Freeman, R.E., Harrison, J.S., Eds.; Blackwell Publishers: Malden, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ravinder, R. Ethical issues in collaboration in the aviation ondustry. Tour. Rev. Int. 2007, 11, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chan, W.W.; Mak, B. An analysis of the environmental reporting structures of selected European airlines. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2005, 7, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, B.L.; Chan, W.W.; Wong, K.; Zheng, C. Comparative studies of standalone environmental reports—European and Asian airlines. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2007, 12, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowper-Smith, A.; De Grosbois, D. The adoption of corporate social responsibility practices in the airline industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.S.; Chen, S.H.; Hsu, C.W.; Hu, A.H. Identifying strategic factors of the implantation CSR in the airline industry: The case of Asia-Pacific Airlines. Sustainability 2015, 7, 7762–7783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.J.; Park, S.Y. An exploratory study of corporate social responsibility in the us travel industry. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barich, H.; Kotler, P. A framework for marketing image management. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1991, 32, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Turban, D.B.; Greening, D.W. Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 658–672. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Park, J.W. Impact of a sustainable brand on improving business performance of airport enterprises: The case of Incheon International Airport. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2016, 53, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Zheng, X. An empirical study on the relationship among corporate social responsibility, brand image and perceived quality. Int. J. Adv. Inf. Sci. Serv. Sci. 2013, 5, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Gürlek, M.; Düzgün, E.; Uygur, S.M.; Rendtorff, J. How does corporate social responsibility create customer loyalty? The role of corporate image. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. How does corporate social responsibility benefit firms? Evidence from Australia. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2010, 22, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmones, M.D.M.G.D.L.; Crespo, A.H.; Del Bosque, I.R. Influence of corporate social responsibility on loyalty and valuation of services. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-bdour, A.A.; Nasruddin, E.; Lin, S.K. The relationship between internal corporate social responsibility and organizational commitment within the banking sector in jordan. Int. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2010, 5, 932–951. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhamme, J.; Lindgreen, A.; Reast, J.; Van Popering, N. To do well by doing good: Improving corporate image through cause-related marketing. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, M.; Mura, M.; Bonoli, A. Corporate social responsibility and corporate performance: The case of Italian SMEs. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2005, 5, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, N.R.N.A.; Rahman, N.I.A.; Khalid, S.A. Environmental corporate social responsibility (ECSR) as a strategic marketing initiatives. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 130, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dögl, C.; Holtbrügge, D. Corporate environmental responsibility, employer reputation and employee commitment: An empirical study in developed and emerging economies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1739–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagmann, C.; Semeijn, J.; Vellenga, D.B. Exploring the green image of airlines: Passenger perceptions and airline choice. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2015, 43, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, J.J.; Chuang, M.L. Evaluating corporate image and reputation using fuzzy mcdm approach in airline market. Qual. Quant. 2010, 44, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J. The Evolution of the Services Marketing Mix and Its Relationship to Service Quality. In Service Quality: Multidisciplinary and Multinational Perspectives; Brown, S., Gummesson, E., Edvardsson, B., Gustavsson, B., Eds.; Lexington Books: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, H. Self-schemata and processing information about the self. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 35, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, N.; Mischel, W. Prototypes in Person Perception. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; Volume 12, pp. 3–52. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, T.W.; Lindestad, B. The effect of corporate image in the formation of customer loyalty. J. Serv. Res. 1998, 1, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindestad, B.; Andreassen, T.W. Customer loyalty and complex services. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1998, 9, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, J.E.; Zhang, A. Corporate image, loyalty, and commitment in the consumer travel industry. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 568–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Pérez, A.; Del Bosque, I.R. CSR influence on hotel brand image and loyalty. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. De Adm. 2014, 27, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. A National customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, R.T.; Zahorik, A.J.; Keiningham, T.L. Return on quality (ROQ): Making service quality financially accountable. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. How Consumers Evaluation Processes Differ Between Goods and Services. In Markeing Services, Proceedings of Ama’s Special Conference On Services Marketing; Donnely, J.H., Gerorge, W.R., Eds.; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1981; pp. 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, I. Pillsbury proves charity, marketing begin at home. Mark. News 1997, 31, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 591–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, K.; Fishbach, A. A recipe for friendship: Similar food consumption promotes trust and cooperation. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Tang, L.; Lee, J.Y. Self-congruity and functional congruity in brand loyalty. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, K.; Olivola, C.; Pronin, E. Do we give more of our present selves or our future selves? Psychological distance and prosocial decision making. ACR North Am. Adv. 2009, 36, 190–194. [Google Scholar]

- Creyer, E.H. The influence of firm behavior on purchase intention: Do consumers really care about business ethics? J. Consum. Mark. 1997, 14, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M.K.; Yi, Y.; Bagozzi, R.P. Effects of customer participation in corporate social responsibility (csr) programs on the csr-brand fit and brand loyalty. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 57, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, N. How to win the battle of ideas in corporate social responsibility: The international pyramid model of CSR. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2017, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, S. Value creation model through corporate social responsibility (CSR). Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 6, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.; Hall, A.D.; Momentè, F.; Reggiani, F. What corporate social responsibility activities are valued by the market? J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, H. Does the market value corporate environmental responsibility? An empirical examination. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, K.; Trendafilova, S. CSR and environmental responsibility: Motives and pressures to adopt green management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.S.; Chiu, C.J.; Yang, C.F.; Pai, D.C. The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Del Bosque, I.R. Measuring csr image: Three studies to develop and to validate a reliable measurement tool. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Del Bosque, I.R. CSR and customer loyalty: The roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Wang, R.; Yang, W. Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do Consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The Impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Raykov, T. On measures of explained variance in nonrecursive structural equation models. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.T.; Hu, H.H. ‘Sunny’ The mediating role of relational benefit between service quality and customer loyalty in airline industry. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2013, 24, 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, L.J.; Vinke, J. CSR reporting: A review of the Pakistani aviation industry. South Asian J. Glob. Bus. Res. 2012, 1, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.A.; Chew, B.C.; Hamid, S.R. Benchmarking key success factors for the future green airline industry. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 224, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International, A.C. Passenger Traffic 2017. Available online: https://aci.aero/data-centre/annual-traffic-data/passengers/2017-passenger-summary-annual-traffic-data/ (accessed on 27 June 2019).

- Tang, W.W. Impact of corporate image and corporate reputation on customer loyalty: A review. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2007, 1, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, A.E.; Rosenberger, P.J., III. The effect of corporate image in the formation of customer loyalty: An australian replication. Australas. Mark. J. 2004, 12, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, I.M. Perceived value, service quality, corporate image and customer loyalty: Empirical assessment from pakistan. Serb. J. Manag. 2012, 7, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Rimmington, M. Tourist satisfaction with Mallorca, Spain, as an off-season holiday destination. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Question | Source |

|---|---|---|

| ECON |

| [70,71,22] |

| LAW |

| [68,70] |

| PHIL |

| [70,71] |

| ENV |

| [31,72,73,74] |

| Factor | Question | Source |

|---|---|---|

| CI |

| [75,76] |

| Factor | Question | Source |

|---|---|---|

| CL |

| [54,77] |

| Factor | Question | Source |

|---|---|---|

| CSRE | Have you ever experienced airline CSR activities? | [78,79] |

| Variables | N | % | Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Income (unit: KRW/month) | ||||

| Male | 63 | 31.5 | Less than 1 million | 17 | 8.5 |

| Female | 137 | 68.5 | 1 million–1.9 million | 22 | 11.0 |

| Age | 2 million–2.9 million | 37 | 18.5 | ||

| Less than 30 | 41 | 20.5 | 3 million–3.9 million | 52 | 26.0 |

| 30–39 | 84 | 42.0 | 4 million–4.9 million | 36 | 18.0 |

| 40–49 | 55 | 27.5 | More than 5 million | 36 | 18.0 |

| 50–59 | 19 | 9.5 | Preferred Airline | ||

| More than 60 | 1 | 0.5 | Korean Air | 133 | 66.5 |

| Job | Asiana | 21 | 10.5 | ||

| Service | 94 | 47.0 | Low-cost carrier | 20 | 10.0 |

| Office worker | 60 | 30.0 | Foreign carrier | 16 | 8.0 |

| Student | 15 | 7.5 | Others | 10 | 5.0 |

| Housewife | 10 | 5.0 | Marriage | ||

| Others | 7 | 3.5 | Yes | 125 | 62.5 |

| Self-employment | 7 | 3.5 | No | 75 | 37.5 |

| Fieldworker | 5 | 2.5 | Airline CSR experience | ||

| Public servant | 2 | 1.0 | No | 67 | 33.5 |

| Education | Direct | 35 | 17.5 | ||

| Less than high school | 8 | 4.0 | Indirect | 98 | 49.0 |

| College | 23 | 11.5 | CSR experience | ||

| Undergraduate | 136 | 68 | No | 129 | 64.5 |

| More than graduate | 33 | 16.5 | Yes | 71 | 35.5 |

| Total | 200 | 100 | Total | 200 | 100 |

| Fit Index | Measurement Model | Accept | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFA | CFA | Difference | ||

| Comparative fit index (CFI) | 0.858 | 0.881 | 0.023 | Good |

| Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) | 0.839 | 0.862 | 0.023 | Good |

| Standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) | 0.067 | 0.062 | −0.005 | Good |

| Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) | 0.079 | 0.076 | −0.003 | Good |

| Variables | Item | Convergent Validity | Reliability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FL (>0.5) | CR (>0.7) | AVE (>0.5) | Cronbach’s α (>0.7) | ||

| ECON | ECON2 | 0.763 | 0.669 | 0.541 | 0.706 |

| ECON3 | 0.643 | ||||

| ECON4 | 0.596 | ||||

| LAW | LAW1 | 0.580 | 0.865 | 0.564 | 0.802 |

| LAW2 | 0.692 | ||||

| LAW3 | 0.893 | ||||

| LAW4 | 0.691 | ||||

| LAW5 | 0.775 | ||||

| PHIL | PHIL1 | 0.823 | 0.898 | 0.638 | 0.897 |

| PHIL2 | 0.823 | ||||

| PHIL3 | 0.864 | ||||

| PHIL4 | 0.725 | ||||

| PHIL5 | 0.752 | ||||

| ENV | ENV2 | 0.695 | 0.849 | 0.586 | 0.839 |

| ENV3 | 0.806 | ||||

| ENV4 | 0.834 | ||||

| ENV5 | 0.719 | ||||

| CI | IMAGE1 | 0.544 | 0.811 | 0.527 | 0.792 |

| IMAGE2 | 0.769 | ||||

| IMAGE3 | 0.823 | ||||

| IMAGE4 | 0.808 | ||||

| CL | CSR1 | 0.624 | 0.858 | 0.673 | 0.835 |

| CSR2 | 0.953 | ||||

| CSR3 | 0.851 | ||||

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ECON | 0.736 | |||||

| 2. LAW | 0.585 * | 0.751 | ||||

| 3. PHIL | 0.629 * | 0.596 * | 0.799 | |||

| 4. ENV | 0.461 * | 0.498 * | 0.422 * | 0.766 | ||

| 5. CI | 0.489 * | 0.596 * | 0.441 * | 0.347 * | 0.726 | |

| 6. CL | 0.222 * | 0.207 * | 0.275 * | 0.311 * | 0.218 * | 0.820 |

| Hypothesized Paths | Coefficients | t-Value | Hypothesis Testing | Goodness-of-Fit Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 ECON → CI | 0.122 | 0.66 | Rejected | = 2660.87 df = 276 /df = 9.641 RMSEA = 0.073 CFI = 0.893 TLI = 0.876 SRMR = 0.065 |

| H2 LAW → CI | 0.090 | 0.64 | Rejected | |

| H3 PHIL → CI | 0.116 | 1.09 | Rejected | |

| H4 ENV → CI | 0.463 | 4.11 *** | Supported | |

| H5 CI → CL | 0.303 | 4.26 *** | Supported | |

| H6 CI × CSRE → CL | 0.143 | 2.08 * | Supported | |

| Total effect on CL = 0.056 = 0.059 = 0.033 = 0.214 ** = 0.399 *** = 0.044 * | Total effect on CI = 0.141 = 0.148 = 0.086 = 0.538 *** R2 of Bentler-Raykov = 0.474 = 0.117 | Indirect effect on CL = 0.056 = 0.059 = 0.033 = 0.215 ** | ||

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t-Value | Coefficient | t-Value | |

| Gender | −0.017 | −0.217 | 0.059 | 0.915 |

| Age | 0.103 | 1.086 | −0.018 | −0.236 |

| Marriage | −0.044 | −0.496 | −0.042 | −0.590 |

| Education | 0.097 | 1.323 | 0.093 | 1.600 |

| Income | −0.027 | −0.317 | −0.003 | −0.050 |

| CSRE | 0.209 ** | 2.941 | 0.054 | 0.923 |

| H1 ECON | 0.122 + | 1.730 | ||

| H2 LAW | 0.149 * | 2.020 | ||

| H3 PHIL | 0.127 + | 1.826 | ||

| H4 ENV | 0.391 *** | 5.274 | ||

| Observation | 200 | 200 | ||

| R2 | 0.059 | 0.422 | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.029 | 0.391 | ||

| Log-likelihood | −135.4 | −86.70 | ||

| Overall F | 2.002 * | 13.78 * | ||

| Changes in R2 | 0.363 | |||

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 (CSRE = No) | Model 5 (CSRE = Yes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −0.073 | −0.070 | −0.060 | −0.030 | −0.125 |

| (−1.083) | (−1.059) | (−0.920) | (−0.307) | (−0.995) | |

| Age | 0.077 | 0.062 | 0.072 | 0.178 | −0.073 |

| (0.948) | (0.777) | (0.908) | (1.478) | (−0.522) | |

| Marriage | 0.109 | 0.115 | 0.125 | 0.134 | 0.235 |

| (1.419) | (1.515) | (1.660) | (1.249) | (1.586) | |

| Education | −0.038 | −0.052 | −0.060 | −0.147 | 0.170 |

| (−0.612) | (−0.833) | (−0.978) | (−1.641) | (1.499) | |

| Income | −0.047 | −0.043 | −0.055 | −0.112 | −0.011 |

| (−0.645) | (−0.600) | (−0.761) | (−1.037) | (−0.082) | |

| CSRE | 0.510 *** | 0.481 *** | −0.719 | ||

| (8.415) | (7.849) | (−1.293) | |||

| H5 CI | 0.139 * | 0.050 | 0.043 | 0.488 *** | |

| (2.287) | (0.686) | (0.486) | (4.642) | ||

| H6 CI CSRE | 1.225 * | ||||

| (2.171) | |||||

| Observation | 200 | 200 | 200 | 129 | 71 |

| R2 | 0.313 | 0.331 | 0.348 | 0.085 | 0.343 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.292 | 0.307 | 0.320 | 0.040 | 0.281 |

| Log-likelihood | −196.9 | −194.2 | −191.8 | −141.8 | −26.43 |

| Overall F | 14.7 * | 13.6 * | 12.7 * | 1.9 * | 5.6 * |

| Changes in R2 | 0.018 | 0.035 | −0.228 | 0.030 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.S.; Kim, Y.; Roh, T. Modified Pyramid of CSR for Corporate Image and Customer Loyalty: Focusing on the Moderating Role of the CSR Experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174745

Lee SS, Kim Y, Roh T. Modified Pyramid of CSR for Corporate Image and Customer Loyalty: Focusing on the Moderating Role of the CSR Experience. Sustainability. 2019; 11(17):4745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174745

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seojin Stacey, Yaeri Kim, and Taewoo Roh. 2019. "Modified Pyramid of CSR for Corporate Image and Customer Loyalty: Focusing on the Moderating Role of the CSR Experience" Sustainability 11, no. 17: 4745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174745

APA StyleLee, S. S., Kim, Y., & Roh, T. (2019). Modified Pyramid of CSR for Corporate Image and Customer Loyalty: Focusing on the Moderating Role of the CSR Experience. Sustainability, 11(17), 4745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174745