4.1. Actors’ Perceptions of SFSCs’ Contributions to Social Sustainability

Social sustainability is here discussed by focusing on how the participants viewed SFSCs in terms of strengthening social capital and local community building. This is analysed first by presenting results from the customer survey on how respondents first visited or were recruited to the SFSC as an indicator of how SFSCs are socially embedded in the local community. These results are discussed against evidence from the in-depth interviews with SFSC participants about the importance of cooperation and personal knowledge to strengthen local networks. This is also analysed in relation to how direct contact between producer and consumer is viewed in terms of sociability, knowledge of food production and how this affect trust and support for local food production among participants of the SFSC.

4.1.1. Local Identity and Community Building

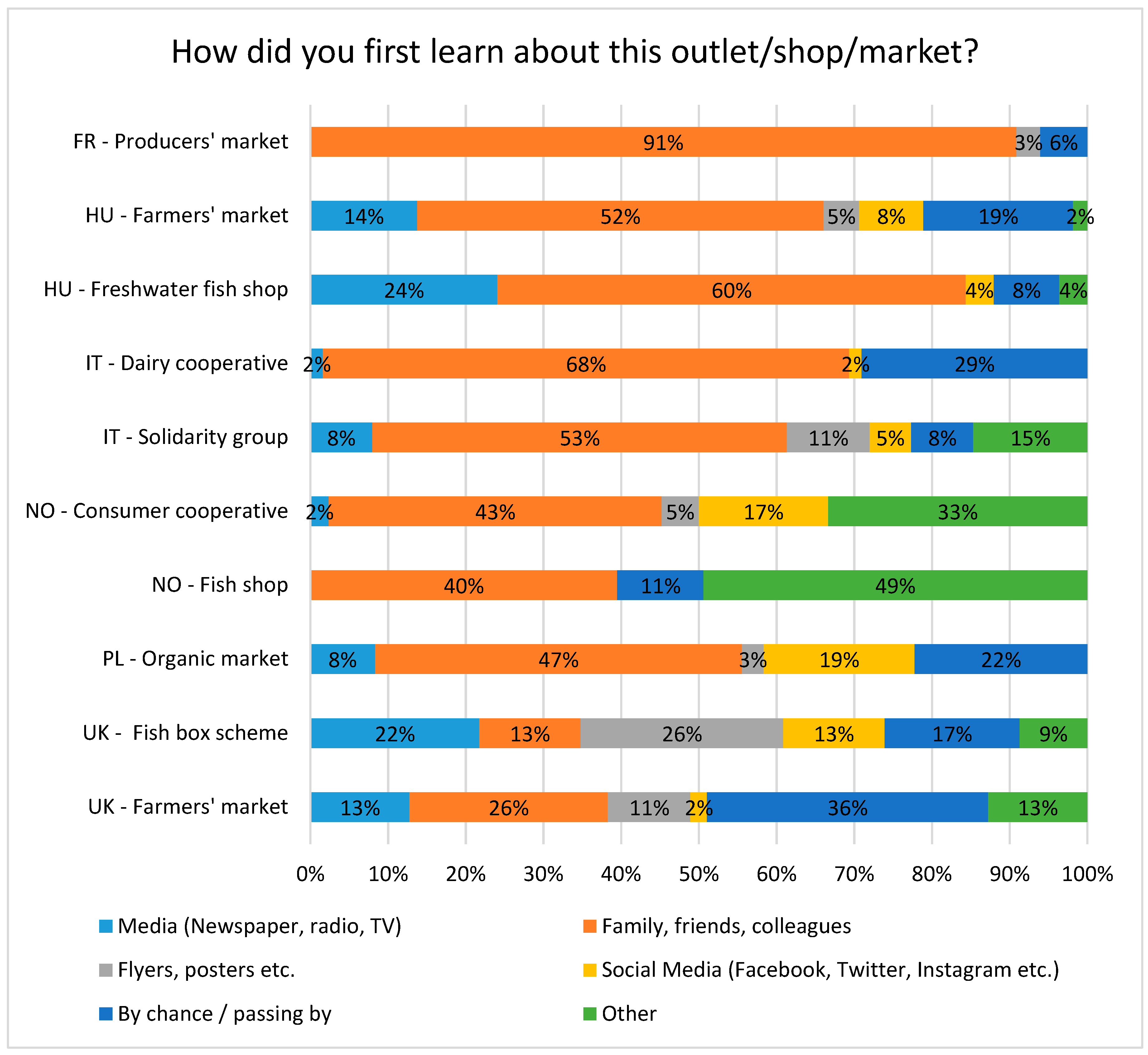

SFSCs may be viewed both as part of existing local networks, as institutions that historically have been present as part of the local community, e.g., farmers markets and local food stores, or they may be new initiatives aimed at building and developing new relations between food system participants in the local community. In this study, we wanted to know how customers first got to know the SFSC as an indicator of local and social embeddedness (

Figure 1).

The dominating answer to this question was: ‘Through family, friends and colleagues’ in many of the cases. In some cases, the question was met with confusion, and comments from the respondents such as: “What do you mean?” and “This shop has always been here” or “I have always known about it” “I remember coming here with my grandmother as a child” (Norwegian Fish shop). In the French Central market (Dijon), this question was asked, but considered irrelevant by the customers because it was so well-known. From the in-depth interviews with customers at the market, continuity in certain families was observed, for instance by customers saying that their parents and grandparents used to come to the same stall, where the producer’s father was. For some consumers, this market is a matter of long-term relations, of trust, respect, sometimes even friendship. Similarly, in the Norwegian Fish shop case, one of the retailers explained that he felt it almost as an obligation to take over the shop, which was a traditional shop established in 1948. When the owners were thinking of retirement, he described his sentiments like this: “This shop is an institution in this town that someone just had to take care of” (Retailer 2, Norwegian Fish shop). There was a similar situation in the Italian Dairy case, where almost all the respondents (N = 60) said they learnt about the selected SFSC thanks to family, friends and colleagues (N = 42). In this case, the retailer said: “The dairy cooperative shop has always been there (…). Those who were involved in the dairy sector and moved in the neighbouring regions, once coming back were looking for our product, so there was a strong demand that remained over time and that allowed the shop to increase its activity”.

Most of the studied SFSCs are not only experienced as places to buy food, but the social dimension is equally strong, also in the most traditional markets where the purchase of ordinary food products is part of daily or weekly routines such as at the Polish Farmers’ market in Płońsk. Here, the customers declared that they liked to socialise at the market:

“I always do the shopping here, this is a tradition, people are nice, it’s good to talk to them” (Consumer 1). “There is a nice atmosphere here, everyone knows each other” (Consumer 3, Polish Farmers’ market). “There is a family atmosphere here, I meet many people I know here” (Consumer 4, Polish Farmers’ market).

Even though in many cases there is competition between producers, for instance at traditional food markets and farmers’ markets, the producers said they cooperated and benefited from the close network that participation in SFSC provided. Thus, the focus was more often on the benefits of cooperation than potential conflicts or competition. Producers at the Central market in Dijon emphasised that the close relations to the customers were important in building loyalty, and networks and cooperation with other producers were important for running the business as, for example, the possibility of buying from each other when running out of their own produce. The solidarity and harmony within the network was also underlined at the UK Farmers’ market: “…getting to know some of the other traders, the way they run their business. Hexham is a good example, really good atmosphere, some good regular customers and good traders there” (Trader 4, UK Farmers’ market).

In the newer initiatives, such as the Norwegian Consumer cooperative, the focus was not on sustaining traditional networks but rather on creating new ones: farmers, who were used to operate autonomously, appreciated the opportunity for participation in this network, which also led to cooperation with the other farmers in other settings than the cooperative. With regard to supplying products to the cooperative, there was a focus on supplementing each other rather than competing in delivering the same type of products. An attitude of respect and goodwill towards each other was apparent. One of the farmers expressed the view: “I very much appreciate the farmer-network. (…) We have in a way a cooperation” (Farmer 1/Organiser). Although there was competition among farmers at the Hungarian Farmers’ market, they also expressed the advantage of cooperating with each other. Here, the main competition was perceived as coming from the larger retailers. These organising principles of autonomy on the one hand and cooperation in close networks on the other were appreciated and regarded as distinctively different from the conventional food system with its hierarchical structure, which, as we will come back to later, is often experienced as a disadvantage to the producer, especially regarding price [

33].

From the interviews with producers and retailers, we found few negative expressions towards cooperation and competition between producers or between producers and retailers, rather the positive aspects were emphasised. These findings are in line with the results of the quantitative producer survey in the Strength2Food project [

33], where the SFSCs overall scored higher than “long chains” on perceived bargaining- and market power (the indicator included factors such as influence, trust, relations with other producers and consumers) as well as general satisfaction with participation in the chain (“I like it”). As mentioned, the critique from the producers was directed towards competition from other actors, such as larger retailers. However, following Malak-Rawlikowska et al., this picture is not straightforward. Several producers also emphasised that hypermarket chains are trustful business partners that opens for sale of larger quantities of products to reasonable prices [

33]. The benefits of large-scale retail were also emphasised by one of the organic producers in the Norwegian Consumer cooperative. He appreciated the cooperation with the conventional retail chain because in this way organic food became more accessible and affordable for ordinary consumers.

A sense of community was valued not only among producers, but also among consumers and between participants with different roles in the SFSC. Connecting with the producers, including fishermen, and supporting the local economy were among the aspects appreciated by consumers: “It feels much, much more connected with the people who are fishing…it feels different [from the supermarket] because it feels like my money might stay in the local community” (Consumer 2, UK Fish case). Personal knowledge of the producers also appeared as an important value: “I absolutely love it…I just find it absolutely delightful to know who your producers are and to buy local stuff” (Consumer 4, UK Farmers’ market). A member of the Norwegian Consumer cooperative pointed at the way in which the cooperative was embedded in and further strengthened the existing local social network: “The most important reason why I participate is that I know so many of those who are involved and organise it, and that it takes place here. Because it is a kind of ‘local community-thing’. It is kind of a small group of people who say: ‘We think that this is important’. Thus, you support them. (…) It ‘lubricates’ the local community” (Consumer 3, Norwegian Consumer cooperative).

The value of direct, face-to-face contact and the way it is seen to provide for good communication was also underlined by producers: “That’s what I like with the concept of the Consumer cooperative: That there is a direct sale between farmer and consumer. […] The more direct sale, the stronger the communication, I believe” (Farmer 4, Norwegian Consumer cooperative).

4.1.2. Strengthen Knowledge and Competencies

The transparency and proximity—social as well as spatial—provide for opportunities of gaining insight and knowledge in a personal and direct way. These forms of gaining knowledge—e.g., information exchange, direct observation, dialogue, becoming aware of connections and complexity in food production—were highlighted by consumers, and also emphasised by producers.

Personal familiarity and sense of connection with the farmer as well as with the particular place, nature and animals was valued for several reasons. In the example below member of the Italian Solidarity purchasing group relates the place of food production to food quality: “buying directly from the farmer, I have direct knowledge of what I eat and its origin, in particular where the crop fields are located, the water used. For example, a local farmer produces very tasty vegetables and when I went to him I discovered that it is due to the fact that he uses water coming from his private well” (Consumer 5, Italian Solidarity purchasing group). Similar experiences of the value of knowledge obtained from personal contact with the producer are described from the UK Farmers’ market: “[It’s about] the provenance, isn’t it? It’s knowing where they’ve been bred, where they come from…what their welfare’s like. It’s having that contact direct with the producer which is just…you can’t replace that in my view…You’d know how it’s been reared. You know a lot more about it and you can go and find out more about it. You know talking to the people who’ve bred the animals very often there is…it’s that immediacy of contact. I like that” (Consumer 3, UK Farmers’ market).

From the producers’ side the direct and personal communication with customers was also valued for several reasons; one of them being the way in which the insights gained through these conversations could be actively used in improving practices and food products: “There are several customers (…) who have asked actively—‘what are the hens eating?’ for example. And, then I can tell them what they eat. And then they might say ‘well, but isn’t it possible to get any grain feeds without soy?’, for example. And that may push me—or other farmers—towards thinking ‘yes, perhaps I can try to achieve that.’ Last year I did in fact get hold of a feed product, ‘Norgesfôr’, without soy, and then I changed to that. I didn’t even know about it, and there were several other small-scale farmers who were unaware of it, and then we all changed” (Farmer 4, Norwegian Consumer cooperative).

This story goes on, further inspiring collective action among the local farmers. It turned out that this particular feed stopped being produced by the large market actor. Faced with this challenge, several of the local farmers cooperated in placing a common order to another main market actor: “But now several farmers have cooperated about a common order to ‘Felleskjøpet’, (Felleskjøpet’ is a Norwegian farmers’ cooperative) so now they have started producing one type of feed [without soy]—because there were enough who requested it. So—if the customer hadn’t asked for it, I am not certain that I would have involved myself in it—perhaps I wouldn’t have even thought about it. I completely agree that it is better with proteins from Norway in the grain feed, than soy from Argentina—even if that may be organic. Then the feed gets a bit more expensive, but—this is an example of how the consumer may affect change—and I am more than willing to be influenced” (Farmer 4, Norwegian Consumer cooperative). This is one example of how the embeddedness of the SFSC in the local community can function as a support in identifying common values and strengthening the compliance of food production with these common values.

New information and experiences, practical knowledge and change of food habits and valuations of food are among the gains reported from participating in SFSCs. Practical help with filleting fresh fish is one example of useful information gained from personal contact within the SFSC, as described by a customer from his/her contact with the fishmonger: “Very good and very helpful—e.g., stop the scheme when going on holiday—fishmonger at the centre very friendly, taught me a few times how to fillet—happy with the relationship” (Consumer 2, UK Fish case). Similar experiences with practical advice from the producer are reported from the UK Farmers’ market: “The man on the [vegetable] stall is good at suggesting ways to cook it or what you could do with it. It’s the same with the people at the meat stalls” (Consumer 5, UK Farmers’ market). A further example of how new products and food habits were established because the household took part in a SFSC came from the Norwegian Consumer cooperative, where a member told the following story about how kale became integrated in their food habits as a consequence of appearing in the ‘vegetable bag’—which is ordered as an unspecified seasonal selection of vegetables—accompanied with a recipe. The customer described changes that had occurred due to their membership: “Kale, for example, which we otherwise would not get much of. (…) There is a recipe of kale-chips, which has become very popular from when I came home with the first bag. (…) The kids like it very much. (…) Now, the kids are very content when there is kale [in the bag], because then there will be kale-chips one day” (Consumer 3, Norwegian Consumer cooperative). Another member in the same cooperative described what she valued the most like this: “The joy of vegetables, which I do not get in the ordinary food store, and completely fresh! (…) It has contributed to new dishes. Twice a week, I make a new type of dish that I otherwise would not have made” (Customer survey, 21, Norwegian Consumer cooperative). From the UK Farmers’ Market, there were accounts of how getting their food from the Farmers’ Market influenced the likelihood of cooking a ‘proper meal’: “If I have bought some vegetables and some nice meat from the farmers” market I am more likely to go home that evening and cook a proper meal from scratch whereas if I am in a supermarket and buy vegetables I might be lazy and buy something quite easy to heat up’ (Consumer 5, UK Farmers’ market). These examples illustrate some of the ways in which taking part in a SFSC can inspire changes in food practices, including types of products used, cooking skills and types of dishes made. All the examples above may serve to illustrate how food—in all the phases of interaction; production, provisioning, preparation and eating—may provide for opportunities for making connections with other people, and local food initiatives have particularly much to offer in this respect. Stevenson has put forward the notion of ‘human infrastructure for negotiating alternative agrifood systems’, referring to collective capacities—or competencies—required to facilitate ‘alternative visions and explorations toward preferred food systems’ [

36]. Meeting places, such as those provided in SFSCs, may serve to inspire and strengthen such competencies and through that facilitate developments of more sustainable food system solutions.

4.1.3. Trust

SFSCs may play an important role in bringing together different types of economic and social actors within a local community. As SFSCs are generally regarded as more transparent and personal alternatives to conventional/large retail chains, consumers may put more trust in them. This was also confirmed by the respondents of the customer survey, responding to the statement “I trust this outlet/shop” (

Figure 2).

Overall, customer survey results indicate high levels of trust in all 12 cases. However, there were some differences. These differences could reflect different forms of organisation of the SFSCs, or differences in the general levels and types of trust among the public in different countries/regions. It is common when considering trust relations to distinguish between relations based on personal interaction and trust in impersonal organisation or systems. Trust based on networks and personal relations is often called ‘familiarity’, while impersonal and generalised trust in institutionalised procedures or systems is called ‘confidence’ [

37]. In a previous comparative European study, Kjærnes et al. [

37] describe how different types of trust have manifested themselves within distinctive national configurations. They found associations between trust in food and general levels of trust in public authorities and market actors, and described various types of triangular relations between food system actors. Norway was characterised by high levels of stability and trust in other people and political institutions [

37]. The strong belief in the safety of Norwegian food was found to be largely a matter of generalised confidence where public authorities are trusted to manage and regulate corporate actors in whom consumers have much more limited faith. In Italy, trust as familiarity was prominent—i.e., a strong reliance on networks and personal relations. Considerable dislocation and disruption of its traditional provisioning system, conflict between European, national and regional state authorities, and consumers torn between alternative lifestyles of tradition and modernity were found to characterise Italy ([

37], p. 182). Lower levels of trust in public authorities are also reported for Poland and France compared with EU average [

4].

Besides national variations, the differences observed in

Figure 2 may also be seen as a result of differences in the organisation of the studied SFSCs. One observation is that although the scores on trust were high for all cases, those at the lower end of the scale included more market-type cases, while the cases organised as cooperatives, solidarity groups and box-schemes were all in the high-end of the scores. These results could indicate that the cases in which there was a high degree of direct contact, solidarity and shared values (as e.g., involvement by membership, shared risk, participation in work tasks, etc. could imply) relations of familiarity were more likely to be established. These traits seemed to be associated with the highest levels of trust. Although similar traits may also be present in the market-oriented cases, they may perhaps not be developed to the same extent.

The in-depth interview data provided more nuance and complexity to the customer survey results. In the customer survey, the Polish markets had the lowest score on trust (3.9 and 4.0, on a scale from 1–5). This slightly lower score does not necessarily mean that the customers at the Polish markets are less confident about buying from SFSCs. From the in-depth interviews we found that trust was highly important for the customers at both of the Polish markets.

At the Polish Farmers’ market in Płońsk, one of the consumers expressed trust in producers/sellers in the following way: “I trust producers, I believe they sell healthy products” (Consumer 2, Polish Farmers’ market). Many of the customers had bought food at the market place for years; they trusted the sellers and believed that they would not be cheated by them. Trust in the sellers seemed to be based on tradition and intergenerational bonds.

Trust related to familiarity was expressed in a variety of ways. In several cases, the strong importance of trust in the customers’ choice to participate in a SFSC, and the way in which this makes a significant distinction from shopping in a supermarket was underlined: “Supermarkets are not my scene because I like to have direct contact with the producer. (…) I recognise the merit of the supermarket to provide a faster service compared with our network; on the other hand it doesn’t allow for the creation of a trust relationship with the producer” (Consumer 3, Italian Solidarity purchasing group). “Compared with other shopping experiences, such as those that take place in a supermarket, I recognise a difference in the price, but I prefer to buy in a traditional way because I really trust this shop” (Consumer 2, Italian Dairy cooperative).

One consumer at the UK Farmers’ market described how familiarity with the producer and his/her values inspires trust: “[…] it’s that personal contact we have with the people who are rearing the animals, or producing the cheese, or smoking the salmon. And that gives you confidence that these are the sorts of people who do take the issues of animal welfare, of the welfare of the environment, they do take them seriously” (Consumer 11, UK Farmers’ market).

These differences in the perceptions of trust reflect the diversity of SFSCs where some cases are strongly embedded in the local context, while in others the relation between consumer and producer is looser and perhaps distant. Thus, measures for enhancing trust, such as formal structures and guarantee systems should be developed in accordance with the local context. Direct access to information and knowledge through personal relations or familiarity with place/nature/animals provides for trust in a different way than for example the use of labels would, which relates more to a conventional market context and longer, less transparent chains.

4.1.4. Support for Local Production

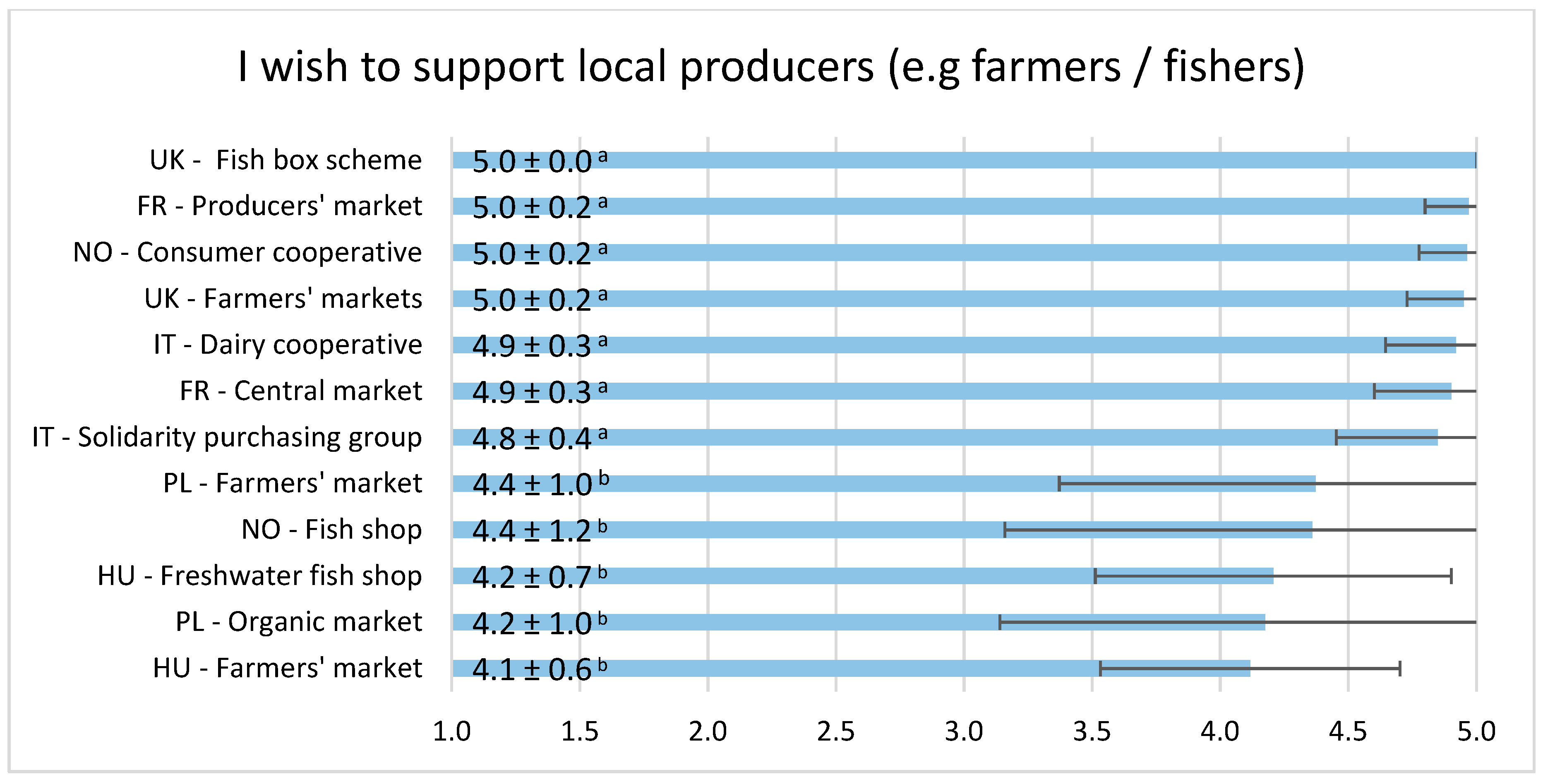

In the customer survey respondents were generally highly positive about the statement “I wish to support local producers” (

Figure 3).

There was a strong support for local food production, local farmers and fishers across all cases, with the lowest levels in the two Polish Farmers’ markets, the fish shops in Norway and Hungary, and the Hungarian Farmers’ market. However, all cases scored above 4. Other reasons for choosing the SFSC may have been important and more in the forefront in these cases—in addition to supporting local producers. A consumer at the Norwegian Consumer cooperative expressing her support for local producers as follows: “I care for the farmers getting paid for what they do. That they have the possibility all the time to improve their production—take care of animal welfare, and not all the time be pressured on price” (Consumer 1).

Supporting local producers appears as an explicit value expressed by consumers in several of the cases—often combined with other motivations, such as animal welfare and product quality. The following quote is from the Italian Dairy cooperative case: “I choose to buy from the shop to support them and because I know the animal living conditions as well as the feed and grazing which characterise the cattle” (Consumer 4). Similarly, the possibility to support local producers is emphasised by a consumer at the UK Farmers’ market, in addition to food-mile benefits: “I tend to go for local, it isn’t just the food-mile side of things, it’s also wanting to support farmers who are at least British or ideally from Northern England or Scotland. It’s about supporting local producers” (Consumer 5).

Similar reflections were expressed in both the UK cases, first from the UK Farmers’ market: “Yes, I would like to see them [farmers’ markets] everywhere because it is the way for the basic producer, the farmer, to get more margins. They certainly cannot from the supermarkets” (Consumer 2). “You know it’s good food, it’s local and that you are helping local producers as opposed to some big supermarket…[I like the fact that it] hasn’t been shipped across the world…and you are helping their businesses” (Consumer 5).

Further, examples come from the UK Fish case: “Money spent by local people on local things, enhance the community rather than money disappearing into some multinational company!” (Consumer 2). “Support local fishermen in Amble and the fishing industry generally in the UK” (Consumer 3). Support for local fisheries were not reflected to the same extent in the Norwegian Fish shop case: “But as long as we have prepared the food and it tastes good and you cannot tell that there is any difference, then I have not reflected on whether it is Swedish, Norwegian or English or something. So I guess perhaps in a way that the salmon and the trout, in any case, is Norwegian, for there is so much of it here.” (Consumer 3). This consumer took it for granted that the fish she used to eat (especially salmon and trout) was from Norway, and did not reflect much over the provenance of fish products. This lack of awareness about local fish was also brought up by another consumer who compared agricultural- and fish products: ’Look at the restaurants nowadays; they often present it like this: ‘We have butter from Røros and we have lamb from Hallingskarvet.’ The only thing [when it comes to fish] has to be bacalao (…), but no, I do not remember that it automatically has been presented (…).” She admitted that she was less conscious about the provenance of fish products compared to agricultural products: “But I’ll do ask the next time (…) Because I do not really ask about: Who has delivered the fish?” (Consumer 2)

The participants’ motivations for supporting local producers and local production were diverse; on the one hand, they related to the social dimension and local development, such as in the two quotes from the UK above (enhance the community, supporting the fishing industry). On the other hand, the support for local producers was as much a matter of transparency and trust and a way to support ethical and environmentally sound food production (such as in the quotes from the Norwegian and Italian consumers). With some exceptions, supporting local producers was viewed as important from a social sustainability perspective while the economic aspect was more contested as will be discussed in more depth in the following section.

4.2. Actors’ Perceptions of SFSCs’ Contributions to Economic Sustainability

4.2.1. Autonomy and Price Setting

Economic reasons were important for the participation of farmers as well as fishers in the SFSCs. Not least, the possibility to gain higher prices than what could be made from selling through wholesalers in conventional food chains, but farmers also emphasised the possibilities for increased turnover and a security to sell. In many of the SFSCs the producers were free to set their own price on the product, and this was perceived as advantageous by the producers with the potential for added-value on their products. One example of a more autonomous price setting was the Italian dairy cooperative that through direct sales gave the producers the opportunity to independently set a price, which was about 10–15% above the market price. The Norwegian local fish case represents an exception because of governmental regulations guaranteeing the fishers a minimum price set by the co-operative sales organisation. This was in contrast to the UK situation, where the bargaining power was perceived weak by the fishers due to large-scale operations by the merchants who control the distribution and set prices.

In the Hungarian Farmers’ market case, which was a hybrid market in the sense that they also included conventional retailers who were buying from larger wholesalers, individual price setting was more limited and smaller producers had to follow the leading price to a strong degree. Hungarian consumers are also more price sensitive; thus, leaving little room for premium price on the products, although the prices at the market in general were higher than in supermarkets. Furthermore, in the Polish Farmers’ market in Płońsk, producers felt the competition on price from local hypermarkets.

4.2.2. Perceptions of Prices

In the customer survey, the respondents were asked the extent to which they find it less expensive to buy from the SFSC than in an ordinary grocery store.

Figure 4 shows differences between the different types of SFSC. The Italian Dairy cooperative was largely perceived as less expensive, which is probably due to the fact that customers in this outlet were being offered special quality products at reasonable prices. Members of the Norwegian Consumer cooperative also to a large extent experienced to be paying less for their products. One main purpose of the Norwegian Consumer cooperative was to supply its members with organic products at affordable prices by removing the intermediaries between farmer and consumer. The traditional markets in Poland and Hungary were also largely perceived as affordable alternatives. The more centrally located city markets and outlets such as the French Central market in Dijon, the Polish Organic market in Warsaw and the Norwegian Fish shop in Sandefjord were, together with the Farmers’ market in the UK, considered to be relatively expensive. This may indicate that these markets to a greater extent catered for more affluent segments of consumers. Higher prices in SFSCs may partly be justified by customers due to higher food quality, reflected by better taste in fruit and vegetables, freshness and longer keeping quality also leading to a reduction in food waste.

4.2.3. Fair Price

The price issue is not without controversy in the cases studied. From the customer survey, as well as the in-depth interviews with producers, retailers and consumers, we found that in some cases the high price of the products was a major barrier for purchase. This was typical for the cases where producers and retailers followed a niche strategy, meaning that they sought to add value through differentiation of products in the market. This was for instance found in markets where producers promoted organic food and speciality products such as at the Central market in Dijon, in the Polish Organic market, BioBazar, as well as at the UK Farmers’ market. In the last case, one of the traders explained: “People are so used to paying very little money for chicken, and when you see a chicken that is maybe 15 pounds [£], their jaws sometimes hit the floor, until you explain why it’s that price” (Trader 4). For this reason, these types of markets may attract devoted customers, highly educated or affluent, while excluding other consumer segments.

In some of the cases the relative higher prices were explicitly linked to solidarity among producers and consumers such as in the Italian Solidarity groups and the Norwegian Consumer co-operative. The Italian solidarity purchasing groups are committed to work towards achieving: “a fair and sustainable economy based on rules of justice and respect for people; fairly in the distribution of value; with transparent criteria in the definition of prices”. In practice, in these networks producers and consumers decide together and agree the price of the products; and in principle, the price should be lower than the retail price for the same product, as they are ordering very large quantities.

However, these principles are tested from time to time and disputes over price do occur in these networks. As described by the consumers, sometimes, the negotiations over price can lead to disagreement or tensions within the purchasing network; this happens if the price requested by the farmer is questioned by the purchasing group. These negotiations may lead the farmers to stop selling their products through the solidarity purchasing group.

To some extent, these disputes over price have changed the initial meaning of the initiative and one important challenge has been for the participants on both “sides” to get out of their roles as producers and consumers and become “co-producers”. The Norwegian Consumer cooperative faces another dilemma regarding pricing of products and support for farmers. The local organic farmers are quite diverse regarding size and the larger farmers may offer the produce at a lower price than the smaller ones. Buying from the larger farmers then gives more vegetables in the bags distributed to the consumers. From a consumer perspective it is not obvious why the amount of vegetables varies while the price of the bag is the same, thus, for the organisers it is challenging to communicate that sometimes there are fewer vegetables in the bag due to price differences between suppliers. Both these cases illustrate how social norms of thrift (acting economically) at the household level can conflict with ethical concerns and evaluations of fairness in the food system. These dilemmas seem especially challenging for the alternative food networks based on solidarity principles between consumers and producers.

4.2.4. Value for Money or the ‘Real Costs’ of Food

Figure 4 above shows that there are great variations between the SFCSs regarding the extent to which they are perceived as less expensive or not. The freedom that producers in many of the cases perceive to set their own price gives room for premium prices on their products. Eliminating intermediaries allows for higher prices to producers, but prices set in SFSCs may also reflect a willingness to pay for high quality and special services by consumers. In addition to quality dimensions such as freshness and taste, products from these SFSCs are valued for a range of aspects (credence qualities) such as animal welfare, environmentally sound food production and sustenance of small-scale, diversified farms. In the customer survey the respondents were asked to react to a stated claim that buying from this SFSC gives more value for money than in a regular grocery store (

Figure 5).

This claim was perceived differently among respondents in the various cases. The respondents in the cooperatives in Italy and Norway strongly agree (score: 4.4) that the SFSC offers more value for money. These two SFSCs also obtained the highest scores on the respondents’ perceived cheapness of the SFSC. At the other end, we found the fish shop in Norway that was evaluated as both being expensive (

Figure 4) and giving less value for money than in the other SFSCs cases. This was also expressed by one of the consumers in the in-depth interview: “If it had been cheaper and easier to go to (the local fish shop), then I had eaten more local fish.” (Consumer 1). The cases with the highest score may reflect that prices in these SFSCs are actually competitive with prices in the regular market, or they may reflect respondents’ willingness to pay for special quality of cheese (Italian Dairy cooperative) and organic and local food products (Norwegian Consumer cooperative).

Although it is evident that the price of food is an important driver for choice for many, there are examples of considerations that the price should reflect the realities behind the food products and the ‘true costs’ [

32] of food produced in line with basic values. Here is an example from a consumer at the UK Farmers’ market: “In an ideal world, I would like it to be illegal for food to be sold at less than it costs” (Consumer 2, UK Farmers’ market). Another example comes from Italy and reflects a wish to get insights into the realities of food production in order to be able to make informed judgements of the fairness of the prices: “We require a product description to understand the production costs and see if it is compliant to the proposed price” (Consumer 2, Italian Solidarity purchasing group).

SFSCs were by many of the producers seen as economically beneficial, but also as fair and just considering the costs of production and distribution. A higher price on their produce may be justified by the fact that it may be more demanding to produce in line with ethical and environmental standards. The dialogue between producer and consumer that can more easily arise in SFSCs may help promote knowledge about the various costs associated with food production.

4.3. Actors’ Perceptions of SFSC’s Contributions to Environmental Sustainability

Issues related to the perceived contributions of SFSCs to environmental sustainability include among others the role of SFSCs in mitigating climate change, with focus on transport distances and CO

2 emissions, reducing resource over-use and waste along the supply chain, improving animal welfare standards and strengthening biodiversity [

19]. Some of these issues are related more directly to the way food is distributed such as travel distances (carbon footprint, food waste), the need for packaging (freshness, food waste) and seasonality (carbon footprint, food waste). Other issues, such as bio-diversity and animal welfare are more indirectly linked, and rest on assumptions that SFSCs imply closer contact and communication between consumer and producers and that this may increase knowledge about food production and act as a driver for sustainable, local food production.

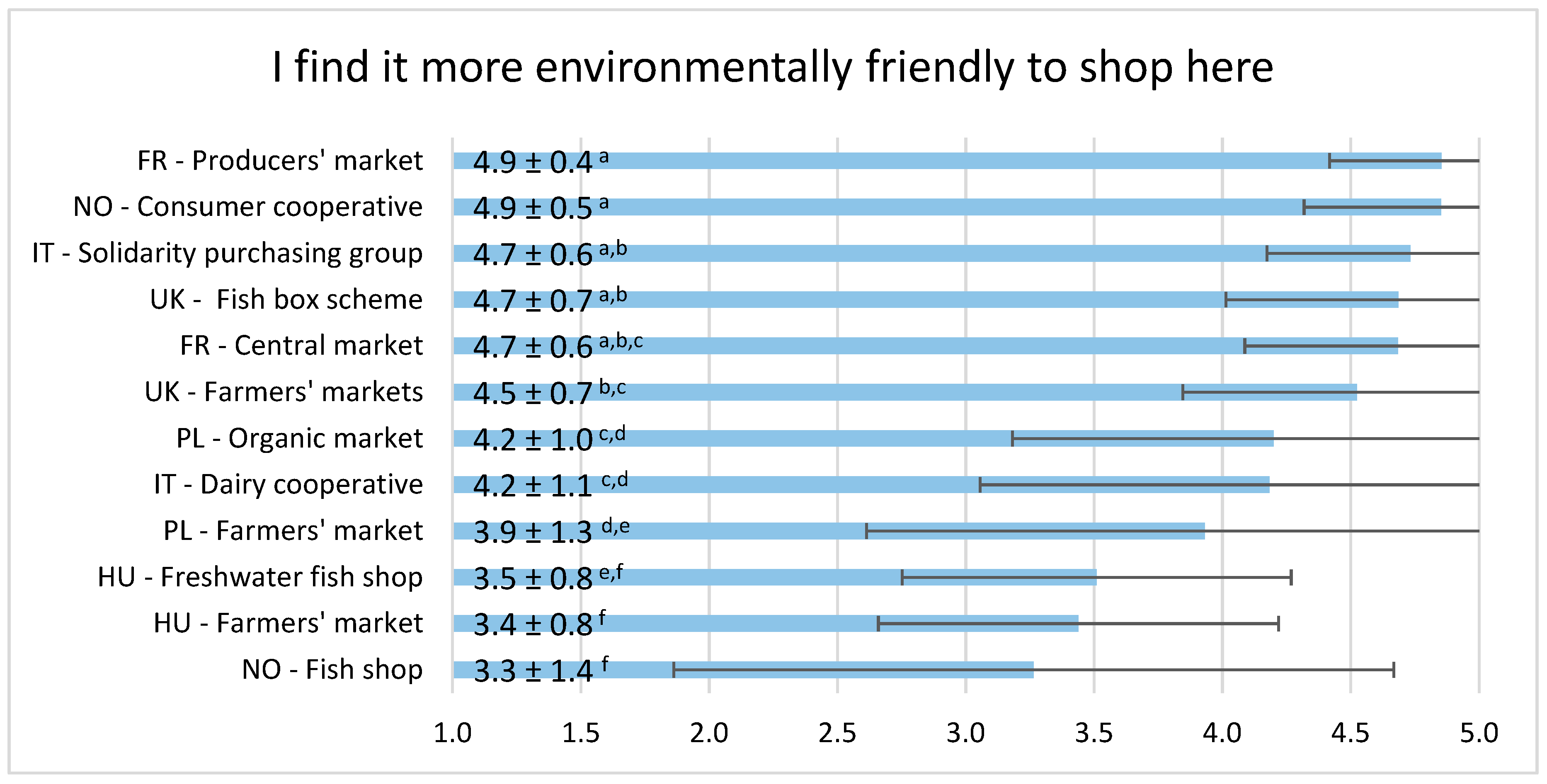

The customer surveys showed that the respondents to a large extent perceived buying from SFSCs as more environmentally friendly compared with buying food in an ordinary grocery store (

Figure 6).

Although all the SFSCs scored relatively high on environmental friendliness (from 3.3–4.9), the newer and innovative SFSCs were in the upper end, while the more traditional SFSCs, such as the Polish and Hungarian Farmers’ markets and the fish shops in Hungary and Norway scored the lowest. This may be due to differences in the customer bases and in the social function of these SFSCs. The former are organised with an explicit aim of supporting sustainable food production and distribution, and likely to attract environmentally conscious consumers, while the other markets are rooted in traditional ways of food provisioning perhaps attracting more “ordinary” consumers.

The customer survey also showed that use of a car was the main mode of transportation with a few exceptions (

Figure 7).

More than 90 percent of the respondents in the French Producers’ market and Italian Dairy cooperative stated that they came by car. The exceptions from the reliance on car transportation were the French Central market in Dijon and the Polish Organic market in Warsaw where public transport equalled the use of cars. Both these markets are centrally located in relatively large cities, and in Dijon as much as 48 percent stated that they came on foot or by bicycle. These findings resonate with previous studies on SFSCs [

19] as well as the quantitative assessments of SFSCs within the Strength2Food project [

33].

From the in-depth interviews with consumers, there were few reflections on the importance of transportation to and from the shop. The use of a car was normally explained by the fact that the market, outlet or pick-up point was most easily accessed by car. It was often combined with other needs or errands (such as transport to/from work or school) and the amount of food bought was not easily transported without the use of a car.

An important motivation for buying food from SFSCs is to support environmentally friendly food production (

Figure 8).

The figure shows the same pattern between the SFSCs as for the question about environmentally friendly shopping (

Figure 6). All 12 cases have high scores (above 3.5) and the newer, innovative SFSCs are at the upper end. From the in-depth interviews with consumers as well as producers and retailers, we found several views on why and how SFSCs enhance environmental sustainability.

4.3.1. Organic and Ethical Food Production and Consumption

The availability of organic food is seen as a valuable asset of the SFSC by consumers across several cases. The Norwegian Consumer cooperative; both the French cases; the Italian Dairy cooperative, the Italian Solidarity purchasing group; the Polish Organic market and the UK Farmers’ market were all (fully or partly) promoting organically produced food. This may also explain the high scores of these cases showed in

Figure 8. These SFSCs thus have the function of providing organic food that otherwise may be less available to conscious consumers, and not least, for many small-scale organic farmers it is an important sales channel. Several values may be combined in the motivation to participate in a SFSC: “I buy through ‘Vestfold Kooperativ’ because it is organic, some is bio-dynamic, and you support local producers. There is a thought behind about helping producers to ‘come up’. It is fresh products, and there is considerably less plastic wrapping” (Consumer 1, Norwegian Consumer cooperative). Similar views were expressed by a trader at the UK Farmers’ market, when explaining his motivations for participating: “Well, a number of reasons: promoting organic food, promoting local food, and just getting the message across about healthy food production, and how not everything has to be how it is through the supermarket (…). The philosophy of the farm is, sort of, ethical, quality production” (Trader 4, UK Farmers’ market).

In the case of the French Central market, producers strongly emphasised avoidance of pesticides and ensuring animal welfare and biodiversity. The consumers at this market also described themselves as committed to these values, e.g., by explicitly going to organic, more expensive producers (partly) to respect environmental concerns. In addition, many of them brought their own bags, reused yogurt pots etc. to reduce waste. Both producers and consumers at this market spoke about their sales/purchases as a way to participate to contribute to making a better world, through responsible consumption.

Awareness of ethical and environmental issues were also at the core of the case of the Italian Solidarity purchasing group: “The main reason is essentially ethical, as was the choice to be organic. For us, ethical means raising awareness among the small producers, who are often sensitive to environmental issues” (Farmer 3, Italian Solidarity purchasing group).

The in-depth interviews with consumers confirm the findings in the customer survey of the perception that products from SFSCs are more environmentally friendly. They often find the supermarket as ‘cold, impersonal, saturated with ads’, and these products (chain produced, industrial, ‘artificial/chemical’) are viewed as being opposed to ‘hand crafted’ products from local farms. With regard to fish as well, consumers value the possibility of sourcing more environmentally friendly alternatives though the SFSC: “Really keen on the fact that it is local and the fact that it is ecologically much more sustainable than fish that’s been brought and packaged and flown half way around the world” (Consumer 2, UK Fish case). Another example from Italy, shows how a consumer became familiar with using other types of ingredients, and caring for animal welfare and the environment: “I’ve learned to cook ingredients that I didn’t know before, I use more herbs and spices and I eat more legumes. From a qualitative point of view, now my diet is more rich in vegetables and sustainable; I try to avoid animal suffering and limit environmental impact” (Consumer 5, Italian Solidarity purchasing group).

Some of the choices farmers make, and values they base their production on, also relate to food quality. Credence qualities such as animal welfare, sustainable production practices and farm management (organic food production, rangeland grazing), nature preservation etc. are difficult to communicate to consumers. Food labelling is often promoted as a mean for differentiating quality food in the food market, but this does not necessarily improve the communication between producer and consumer. However, one main finding from the cases studied was the attractiveness of SFSC to producers of quality food, especially organic farmers and producers that aimed at adapting their production to more sustainable and ethical (animal welfare) production practices. They wanted to combine a ‘natural embedded production’ with a more social embedded distribution of their products in order to promote the qualities of their products in the communication with consumers. Both at the Italian Dairy and the Norwegian Consumer cooperative, farmers explained how their choices in farm management, such as animal breed, grazing and the prominent role of high animal welfare, are connected to the quality of milk and cheese: “In the plains, farms have improved productivity a lot and are more industrialised, while in the mountains we still have traditional stables and feed” (Farmer 5, Italian Dairy cooperative). “Our products are differentiated for animal welfare. The fodder consisting of fresh grass and the breed of cows; in fact, many say that the milk of the Bruna breed is qualitatively better than other breeds. We have Bruna, Pezzata Rossa and mixed breeds. They certainly produce less milk but of better quality. Grazing cows also improves the healthiness of the products from a hygienic point of view because there is a lot of attention to cleanliness of the cows” (Farmer 4, Italian Dairy cooperative).

Similar considerations of environmental and ethical factors in the choice of breeds were reflected among Norwegian farmers: “They are cross-bred of old breeds. […] Jarlsberg and Telemark are the main breeds. And they fit well in this management, because we farm extensively with little grain feed, and then it is smart to have animals which are well-suited for that sort of production. And then they are good at transforming grass, and they milk on it, and they are smaller animals, which move easily in the terrain—they are good at grazing, and good mothers—they calve easily. (…) It is a breed that belongs to this area, and then it makes sense to use it, really” (Farmer 4, Norwegian Consumer cooperative).

The same farmer keeps 250 hens, which have access to 2 hectares of fenced outdoor area, in addition to the indoor hen house. He compares his egg production to one of the largest producers of organic eggs in Norway. Eggs from both farms are actually sold side-by-side in the same speciality shop: “In the shop, those eggs both appear as ‘organic’, while within the Debio-regulations, you may have a chicken farm with 7500 hens under one roof—which is a tremendously large industrial production, in my view. And here it is a small chicken farm—so I cannot compete with him on price. But both is ‘organic’. But—there is a large difference in animal welfare, in my opinion” (Farmer 4, Norwegian Consumer cooperative). These features of the production are also perceived as influencing the product quality—and problematises differences within certified organic production: “And the consistency [is different], for all of mine go outdoors and eat grass, and I am not so sure if his gets to do that, because when you have that many hens, then you must have 2 hectares of area, for it to be comparable,—and it may not be that they would use that area in the same way, because—if it isn’t covered with bushes and trees, they don’t dare to go far out onto a field, you know. So when the scale increases, it wouldn’t necessarily be the same—even if it is ‘Debio [approved]” (Farmer 4, Norwegian Consumer cooperative).

The value of nature and preservation of the local natural area (such as traditionally farmed/cultivated landscape), awareness of the ‘terroir’ (contextual characteristics of the land), and a wish to support environmentally friendly production in the local area were all high among consumers in several of the cases. This was for example prevalent in the Italian Dairy cooperative case, where traditional use of grazing in the mountain region is central.

4.3.2. Animal Welfare

Animal welfare is expressed as a core value and motivation among all types of actors across the cases studied. For some of the consumers, this was their number one priority: “I would not buy from anywhere where animal welfare was not important…animal welfare is the most important thing to me above all else” (Consumer 2, UK Farmers’ market). “I have always been very interested about welfare, small abattoirs, that sort of thing, and meat that’s killed with as little stress as possible…” (Consumer 3, UK Farmers’ market). “The main things I would be interested in are that there is good quality of animal welfare, that the animals live outside, are free range and ideally organic” (Consumer 5, UK Farmers’ market). The farmers also underlined their care for good animal welfare: “Our pigs grow quite slowly and quite laid-back… but it takes a lot of human energy to keep them like that. It’s much easier to keep them in a shed, all piled on top of each other, and feed them with shoots and things like that. But that’s not what our product is about, really, or how we would like to keep them. So we walk miles, feeding pigs, checking pigs, and everything, and they have a life of luxury” (Trader 2, UK Farmers’ market).

In some cases, the value of animal welfare is related to the concept of food quality. For instance: less stress in the animals’ lives, as well as in relation to slaughter (transport etc.), is seen as a value in itself, at the same time as it is experienced as having a positive impact on sensory food quality: “One thing is that in small-scale, it is in my opinion easier to succeed with good animal welfare. […] The fact that they are grazing out in the forest in up to five months a year gives a different quality of milk than if they eat silage […] Actually, it is a prerequisite for getting good cheese—that one feeds with hay and not with silage. So—the feeding and animal keeping is designed for high quality—and that will be recognisable in the products” (Farmer 4, Norwegian Consumer cooperative).

The connection between local and direct sourcing and food quality was brought up in the seafood cases as well. Fishers from the UK Fish box case, for example, emphasised that sourcing directly from the fishers implies that seafood comes straight from the sea and, thus, is fresh, local, seasonal and with ‘low stress levels’, hence of the greatest quality. For instance, Fisher 2 highlighted that the flesh of farmed fish and live lobsters in holding tanks with elastic bands on their claws generally present high stress levels affecting the quality of the flesh.

4.3.3. Resource Use and Reducing Packaging and Food Waste

Keeping waste at a minimal level and being conscious of the use of resources were central values for many participants in the SFSCs. Some of the farmers really made an effort to find solutions that would reduce waste and environmental impact and at the same time provide high food quality, as for example the farmers from the Italian Solidarity purchasing group selling vegetables, that were harvested the same day or at most the day before. Two farmers do not have refrigerated storage and almost all were organised in such a way as to reduce environmental impact: “For sale, he uses recycled wooden boxes from the sale of other products, and envelopes for organic material” (Farmer 1, Italian Solidarity purchasing group). A Norwegian farmer emphasised the use of local resources and avoidance of long transportation of animal feed: “We buy very little. That is the key to our system. (…) We aim at producing everything that animals eat here at the farm. It makes very little sense to transport things from far away” (Farmer 3, Norwegian Consumer cooperative).

Avoidance—or limited use—of plastic food wrapping was an important benefit of participating in a SFSC perceived by consumers: “(…) many of the products have substantially less plastic” (Consumer 1, Norwegian Consumer cooperative). Even the way the buying-situation was organised could contribute to making it easier not to waste food: “I like the fact that you can choose the exact number of things you want [at farmers’ markets] and put them straight into your bag. I don’t like all of the packaging in supermarkets which you struggle to avoid” (Consumer 5, UK Farmers’ market).

In some cases, consumers described how participating in a SFSC could help them achieve goals that they had already made for themselves: “I always try to be very careful about not wasting things. It’s one of the reasons that I go to the farmers’ market, to try not to create as much waste in packaging and so forth. But my habit, for a long, long time, has been not to waste stuff” (Consumer 4, UK Farmers’ market). Similar connections between the way of shopping and amount of food waste was described in Italy: “Since I started to do shopping here I give more value to food and I waste much less because I purchase limited amounts of product on a weekly basis” (Consumer 3, Italian Dairy cooperative).

Although environmental sustainability, from the customer surveys, is seen as an important dimension for participation in SFCS in all the 12 cases, we found a difference between the newer, innovative cases, based in the northern and southern European countries, and the more traditional markets in the Eastern Europe. This difference was most apparent in the new innovative cases organised around ethical and social principles, such as for instance the consumer cooperative in Norway, the solidarity group in Italy, the UK Fish box scheme and the French Producers’ market. These SFSCSs function as important distribution channels for producers of organic food and agricultural products as well as fish and seafood produced according to sustainable and ethical principles (animal welfare; resource use, bio-diversity etc.). The SFSCs are also seen to reduce food miles and carbon footprints; however, the reliance on car transport for distribution of small amounts of food was less reflected among the participants.