1. Introduction

A mission statement is the concrete revelation and embodiment of the mission of an enterprise. It describes, in text format, the intention and the reason for the existence of an enterprise. It answers key questions regarding the survival and development of an enterprise, such as “What kind of a company is our company? What kind of a company should we be? What kind of a company we will become in the future?” [

1]. Studies have shown that mission orientation may be connected with some value-relevant outcomes such as financial performance [

2]. A mission statement that is properly stated will function as the guiding principle of the enterprise’s operation, ethics, and financial pursuits, providing norms and codes of conduct for the employees [

3]. In addition, it can communicate to the outside parties the philosophy and value of the company [

4,

5], helping to establish a positive image of the company, and obtaining approval and support from stakeholders.

Mission statements reflect the values of the business environment for which they are constructed, of which many differences may be explained by economic and institutional environment and industry structure [

6]. In the current time of globalization, while enterprises regularly operate across country borders and sell globally, such a global and cross-cultural environment no doubt would significantly impact the formulation of the missions of enterprises. Enterprises based on the cultures and the social-economic context in which they were established and grew would very naturally have such cultural and social-economic characteristics reflected in their missions. Our study will focus on the missions of enterprises in a fast-growing economy: China, whose astonishing growth over more than three decades has made the country and its enterprises the focus of the world. In the examination of the mission statements of Chinese enterprises, there are two interesting and useful angles: the first is from the distinction of the Chinese culture in the spectrum of world cultures, especially the comparison based on the difference between Chinese culture and the cultures of leading industrial countries; the second is the cultural change China is experiencing as the country is playing “catch up” with industrial countries in the modernization of economy and society.

From the former perspective, when viewing the social cultural environment for enterprises based on Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory [

7], there is a consensus that the Chinese culture is distinct in its greater power distance compared to many Western industrial countries such as (especially) the US. Another consensus is that the Chinese culture puts more emphasis on collectivism, while Western cultures, especially American culture, advocate individualism. Such significant differences between Chinese and American societies will no doubt cast unique characteristics in the mission statements for enterprises in the two countries.

From perspective two, as a developing country, China has been playing and is continuing to play “catch up” with Western industrial countries for the past four decades. As the centerpiece of strategic management in the modern business, a mission statement is being adopted by more and more Chinese enterprises as part of the catch-up game. According to Chinese researchers in strategic management [

8,

9], the proportion of companies with a clear statement of values among the top 100 Chinese companies had increased from 42% in 2007 to 72% by 2013. This dynamic process has two clear characteristics: relatively backward [

5] and fast catch up. The dynamics should be reflected in the mission statements of Chinese enterprises as compared to enterprises in Western industrial countries.

To facilitate a comparison of Chinese enterprises and those in Western industrial countries, we used enterprises in the US as a benchmark. On the 2017 Fortune Global 500 list, American companies accounted for a large percentage of 26.4% among all; in addition, the US was the leader in many new technological advancements as well as new business models. Therefore, we chose American companies as our samples of Western industrial countries, for comparison with Chinese companies, to study the difference in mission statements among Chinese companies and those in industrial countries. By such comparison, we hope to provide inspiration for Chinese companies in handling cross-cultural integration and achieving better performance in their globalization; we also hope that we can provide perspectives for companies in Western industrial countries to better understand the values, objectives, and strategic pursuits of Chinese companies from the latter’s mission statements.

Our research goals require that we adopt methods that can examine the research object—with such rich and profound characteristics as corporate mission statements—from a multi-perspective and with multifaceted tools.

1.1. Qualities of Mission Statements

In the assessment of the qualities of a corporate mission statement, researchers often use standards in two categories: the standards of key components, and the standards of stakeholders. The standards of key components hold that a good mission statement must cover related key components for the mission statements to play positive roles in the company’s performance (see, for example, [

10,

11]). However, scholars hold different opinions as to which components are integral to a mission statement. Bart [

10] argued that a good mission statement should contain 25 key components, while David [

11] summarized the key components into nine categories: customers, products or services, location, technology, concern for survival, philosophy, self-concept, concern for public image, and concern for employees. The nine key components theory is popular in the study of mission statements. Lin et al. [

12] employed the nine key components theory to conduct a study comparing the mission statements of private and state-owned companies in China, exploring the differences in the qualities of mission statements among and the concerns of key components by the two types of Chinese companies.

The other school of thoughts—the theory of stakeholders—believe that the long-term survival and development of a company is closely related to its stakeholders. Therefore, in establishing the mission statement, the company must take into consideration the needs of stakeholders. Bartkus and MacAfee [

13] conducted a study comparing the mission statements of US, European, and Japanese enterprises, with the focus on statements based on five types, namely, stakeholders/customers, employees, investors, suppliers, and society. Instead of identifying stakeholders based on a certain stakeholder theory, many scholars identified stakeholders according to earlier research on stakeholders and company’s mission [

14,

15]. The stakeholders identified this way are often incomplete or unsystematic. In order to take all stakeholders into consideration, we can employ a well-established theory, such as the stakeholder theory put forth by Wheeler and Sillanpӓӓ [

16]; it is an inclusive framework which categorizes stakeholders based on social dimensions, namely Social Stakeholders and Non-Social Stakeholders. Given the significant differences between the society of China and that of the US in terms of political and economic institutions, a focus on Social and Non-Social Stakeholders may well present differences between enterprises in the two countries.

1.2. Mission Statement and Appraisal System

A mission statement is one type of application of language; it conveys value, opinion and the attitude of a company to recipients of the message. Communicating the vision of a company was deemed one of the important factors to affect the realization of the vision [

17]. Therefore, the language that is used in a corporate mission statement should be further explored from the perspective that it is an instrument of communication [

4,

17]. Linguistically, the language sources for the author’s opinions, attitudes, and stance are referred to as appraisal system, which was put forth by J.R. Martin (1992) [

18] in his book

English Text: System and Structure. It is particularly helpful to study mission statements from the perspective of linguistics, for the very purpose of exploring the organization’s own positioning and its attitude toward stakeholders, as well as the effectiveness of conveying interpersonal meaning of the mission statement. So far, we have yet to find research on mission statements along the line of linguistic approach. Hence, the starting point of our study is from the perspective of linguistics, to reach a fresh and deeper understanding of mission statements.

The following threads of logic in related theories form the foundation of our methodology in approaching a mission statement study along the line of linguistics: multiple functions of language were summarized by Halliday et al. [

19,

20] as ideational function, interpersonal function, and textual function. This theory is named Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL). Later, J.R. Martin [

18] advanced SFL and established an appraisal system, which first introduced semantics of evaluation into the study of the interpersonal function of languages. The appraisal system includes the three systems of attitude, engagement, and graduation, with attitude being the kernel [

21] (see

Figure 1 below). Attitude refers to the judgment and appreciation of human behaviors, text/procedure, and phenomena by a person, after his/her psychology is influenced [

22]. As such, the attitudinal system is further divided into the following three subsystems: affect system, judgment system, and appreciation system. The affect system is the center of the attitudinal system; it explains the language user’s sentimental response toward behaviors, text/procedure, and phenomena. The judgment system belongs to the domain of ethics; it explains the language user’s ethical judgments of certain behaviors based on ethics/morals (as well as regulations). The appreciation system belongs to the aesthetics domain; it explains the language user’s appreciation of the text/procedure’s and phenomena’s aesthetic characters. The appraisal of the above can be seen as the author’s or the opinion holder’s “interpersonal” tool to establish unity with their audience [

23]. In linguistics, the language resources that express the meaning of attitude are referred to as attitudinal resources; in other words, the words that express the meaning of attitude in the text belong to attitudinal resources. The evaluation and judgment of the attitude meaning in the language can be referred to as attitude evaluation. In practice, the appraisal system is widely employed in the studies of language styles such as news, advertisements, and mottos. However, it is not yet employed in the study of mission statements of organizations.

In summary, the three theories mentioned above have their respective perspectives and emphasis. The appraisal system provides a new method to study the mission statement from the perspective of systemic functional linguistics; the theory of key components pays attention to the analysis of the composition of the mission statement—a special text with strategic significance to the enterprise; and the stakeholder theory analyzes the mission statement from the perspective of stakeholders which the mission statement intends to influence. A combination of those three theories could shed light on an in-depth and complete understanding of a mission statement on its contents and interpersonal function toward broad stakeholders.

2. Research Goals and Methodology

There has been fairly comprehensive research on mission statements. The studies on the qualities of mission statements, however, have been from a relatively narrow perspective with limitations in methodology and samples. Specifically, the commonly used method—content analysis—was conducted directly on concrete words in their literal meaning in the mission statements, without a filtering process to “distill” meaningful words that express the central value and top priority that the enterprise intends to communicate (such as consumer priority, or market orientation). Previous studies on corporate culture or core values including mission statements were mostly qualitative discussions. Quantitative research is limited to the inner level of the organization, with less attention to the inter-organizational level and cross-cultural level [

24,

25]. The selected samples of mission statements in existing studies are confined either within a country or within an industry, which did not allow generalization and the search for universal findings. It is, therefore, necessary to broaden the sample of mission statements, and to optimize the methodology for analyses across industries and across countries, to reach more universal findings.

2.1. Research Samples: The Fortune 500 Companies

We used the mission statements of Fortune 500 companies as the source of our samples. There is a reason for why we looked in Fortune 500 companies. Creating a good mission statement requires a large amount of, and quality of, human resources, which is why smaller companies often do not have their own mission statement. In addition, smaller companies mostly operate and compete in a fairly narrow geographical region or narrow product/service niche, serving relatively fewer customers, that the benefit of communicating the values and goals of the business to a broad range of customers is not as critical as it would be for large corporations. The companies on the Fortune 500 list, on the other hand, are all major companies with strong human resources and have a more genuine understanding of the values and more critical needs for the development of mission statements. Several studies utilize the Fortune 500 list as a sub-sample of large companies in cross-cultural business and management research [

25,

26,

27,

28]. We likewise believed it proper to use companies on the Fortune 500 list as representative samples for our study that focused on cross-country differences in mission statements. Based on the above understanding and reason, we selected, in the order of the Fortune ranking, the top 100 Chinese enterprises and top 100 American enterprises as our subjects of study. We then visited the official websites and/or the annual reports of those subject companies to capture the contents of their mission statements. Relevant terminology, such as “vision”, “principles”, “values”, “goals” and “code of conduct” were also taken into consideration since they were treated as part of the mission statement genre [

29,

30].

The reasons for why we chose Chinese and American companies for comparison are:

- (1).

China is a good representative of emerging economies. A country’s economy depends largely on the economic activities of its domestic companies. Ever since China implemented the “reform and opening” policies, it has gradually established a “socialist market economy” system. However, the home countries of the rest of the fortune 500 companies are mostly countries with a well-developed free market, or “capitalist”, economy, with the US as the most representative. It would be interesting and enlightening to explore the differences between the two economic systems through the comparison of the mission statements of Chinese and US companies.

- (2).

The natures of Chinese and American companies are different because of the differences in the backgrounds of the companies, especially the ownership of the companies. The Chinese companies listed on the Fortune 500 list are mainly state-owned companies; there are only a few Chinese companies on the Fortune 500 list that are not state-owned. However, most of the American Fortune 500 companies are not state-owned enterprises. The vast amounts of profits of Chinese state-owned companies are not obtained solely from the outcome of market competition but are partly, some substantially, from a more or less administratively granted monopoly. While enjoying a monopolistic position, these state-owned companies, in turn, need to perform some government-delegated administrative responsibilities which non-state-owned enterprises do not need to be engaged. Generally speaking, Chinese companies on the Fortune 500 list were established later in time than the majority of their international counterparts and have their own distinct characteristics. For example, when carrying out various activities, these Chinese companies not only need to consider their immediate stakeholders’ benefits, they also need to fulfil their responsibilities in sustaining the economic development of the country and leading the industry’s responses to government policies, since, to these state-owned companies, the state (government) is actually their most important stakeholder. Such differences in enjoying monopolistic advantage (or not) and bearing government-delegated administrative responsibilities (or not) should presumably be reflected in the differences between the mission statements of Chinese and American companies.

- (3).

Mission statements are high-level conscious guidelines for an enterprise; through exploring the similarities and differences in mission statements of Chinese and American enterprises, we can have a better understanding of the development status of Chinese enterprises and that of the Chinese economy, as compared to those of the US.

2.2. Words Screening: The Method of Corpus Analysis

This study will adopt the method of corpus analysis, to conduct a comparative study on the mission statements of Chinese and American enterprises. Because the mission statements captured were systematic and in a large number, we established a small corpus for this study. A corpus, the foundation of the following analysis, was established by words selected from the mission statements of those enterprises based on the appraisal system put forth by J.R. Martin in his 1992 book [

18]. Corpus linguistics is a research methodology that is widely used by scholars in sociology, psychology, and linguistics. It is based on a large amount of linguistic data collected from the object of the study (or its context) to process the data in the form of corpus—to draw conclusions using statistical analysis [

4]. Through using a set of bottom-up research methods—that is, a specific process including extraction, observation, summary and explanation—corpus linguistics takes into account both scientific attributes and humanities characteristics, achieving a good balance between language description and interpretation [

31]. The corpus method enriches and improves the research in related disciplines.

This study employed a unique method in the tallying of the high-frequency words, as compared with common methods in text analysis. The existing research usually counted the frequency of words directly and made an analysis of high-frequency words. They did not select or screen the high-frequency words based on a certain standard. In an analogy, their studies were more “seeing trees” but not so much “seeing the forest.” In this study, however, we screened the high-frequency words according to the attitudinal system of the appraisal theory, in which we identified and discarded the high-frequency words that did not have relevance in evaluating the attitudes (one of the three systems in the appraisal system) [

21]. Continuing the above analogy, our study attempts to examine the “species” or “colonies” in the “forest” rather than just examining individual plants. This method helps to improve the effectiveness of examining the high-frequency words, so that the results could better reflect the interaction between the mission statements and their audience.

2.3. Quantitative Analyses: Three Integrated Aspects

While the standards of key components and stakeholders are common instruments in the analysis of mission statements, studying mission statements from a linguistics point of view is relatively novel. For a mission statement, we not only need to analyze its composition from the perspective of key components and analyze the stakeholders it concerns, from the perspective of stakeholder theory, but also need to understand the effectiveness of the mission statement in communicating to both internal and external audiences, as well as to explore the linguistic characteristics of the mission statement on attitude evaluation [

32]. Therefore, we combined the new perspective of appraisal theory with the mainstream mission statement studies (i.e., the key components theory and the stakeholder theory) to obtain a more comprehensive analysis of the mission statements of Chinese and American companies.

This study first tallied and ranked the attitude words of interpersonal meanings in the corpus, according to the attitudinal system in the appraisal system theory [

21], and then conducted quantitative analyses from the following three aspects: appraisal system theory, key components theory, and stakeholder theory.

From the first of the three aspects above, our study is based on the appraisal system theory [

18], centering on the attitudinal system of the appraisal system. By analyzing the vocabulary used in the mission statements of Chinese and American enterprises, we explored an enterprise’s self-positioning and attitude to stakeholders, as well as the similarities and differences in the interpersonal meaning of the enterprises’ mission statements.

From the second aspect (the key components theory), this paper will apply the nine key components theory [

11] to analyze the mission statements of Chinese and American enterprises. By filtering the attitudinal resources belonging to different components, we will explore the differences in the mission statements of Chinese and American enterprises on the components of the statements.

From the third aspect, this paper will apply stakeholder theory [

16], by selecting the attitudinal resources referring to or attributed to different stakeholders, to determine who the primary focused stakeholders are in both countries, respectively. A comparative analysis will be conducted to explore the similarities and differences in the mission statements of Chinese and American companies on stakeholders.

2.4. Research Goals

Based on the analyses above, we will then attempt to explain the causes of the similarities and differences between Chinese and American enterprises and put forward the corresponding suggestions for the improvement of mission statements for Chinese companies. The purpose of the study is four-fold: (1) to explore the linguistic features of mission statements from the perspective of the appraisal theory; (2) to achieve an understanding of the characteristics of the mission statements of Chinese and American enterprises; (3) to compare the similarities and differences in the mission statements of Chinese and American enterprises, and analyze the possible causes for these differences; (4) to provide suggestions for enterprises for effective mission statement development.

3. The Establishment of High-Frequency Words

3.1. The Establishment of Corpus

This study, based on the 2017 list of Fortune 500 companies, selected 100 Chinese companies and 100 American companies, both by their rank on the list (high to low); then we collected their mission statements to build the corpus for the study. The Chinese company’s mission statements were adopted in their official Chinese version. We analyzed the selected mission statements based on frequency of a resource word, which refers to how many companies mentioned a specific word/attitudinal resource/key component in the mission statements.

3.2. The Establishment of the High-Frequency Words in the Evaluation of Attitudes

To establish the high-frequency words for the evaluation of attitudes, we used the NLPIR word division system [

33], and the AntConc corpus analysis toolkit [

34]. NLPIR and AntConc are popular application software in language processing and text analysis. We first used NLPIR system to single out, from the mission statements, key words rather than sentences. Given that most Chinese words are of two to three characters, and a single Chinese character often does not constitute a word, when encountering words in single Chinese characters, it is not easy to determine their meaning. Therefore, in the single-Chinese-character case, we used the Concordance function in AntConc to find the “partnering” words (two or more Chinese characters) that had a frequency of five or higher, and added all the new words obtained into the dictionary of NLPIR. The reason why we chose a frequency of five as the threshold is that the lowest frequency of the top 100 high-frequency words singled out by NLPIR system is five so that a single Chinese character partnering with words that had a frequency of five or higher should be taken into consideration in the analysis. We then read all the mission statements (Chinese companies and American companies) into AntConc. Word repetitions in a mission statement were removed using the Word List function in AntConc (for example, the word “customer” appears four times in Wal-Mart’s mission statement; it was counted as once, not four times).

The high-frequency words thus obtained were not all attitude evaluation words. Since the words filtered through the appraisal theory can reflect the interpersonal meaning of the mission statement more accurately, the next step is to screen and identify words to establish the high-frequency words for attitude evaluation. We compared the high-frequency words in this study with those known as attitude evaluation words in well-known works of attitude evaluation. We also considered the context of the words based on the definition of attitude evaluation words to conduct individual judgements of the high-frequency words that did not appear in existing well-known works, resulting in the deletion of non-attitude evaluation words, such as “company”, “we”, and “provide”. From the high-frequency words in the mission statements of the Chinese companies, we selected, in descending frequency ranking, the top 100 high-frequency attitude evaluation words while deleting those words that are not of attitude evaluation. We performed the same process on the high-frequency words for American companies’ mission statements and obtained the top 100 attitude evaluation words for American companies’ mission statements. The high-frequency words thus selected express the meaning of attitude, and they belong to attitudinal resources in linguistics. We will employ this term in our discussions in the following sections.

According to Martin and White [

22], the attitudinal resources in the mission statements can further be classified into three subsystems: affect, judgment, and appreciation.

Table 1 presents the breakdown of the attitudinal resources.

4. Comparative Analysis of Mission Statements of Chinese and American Companies

4.1. Similar Overall Pattern in Resources Distribution, with Substantial Difference in Judgment Subsystem

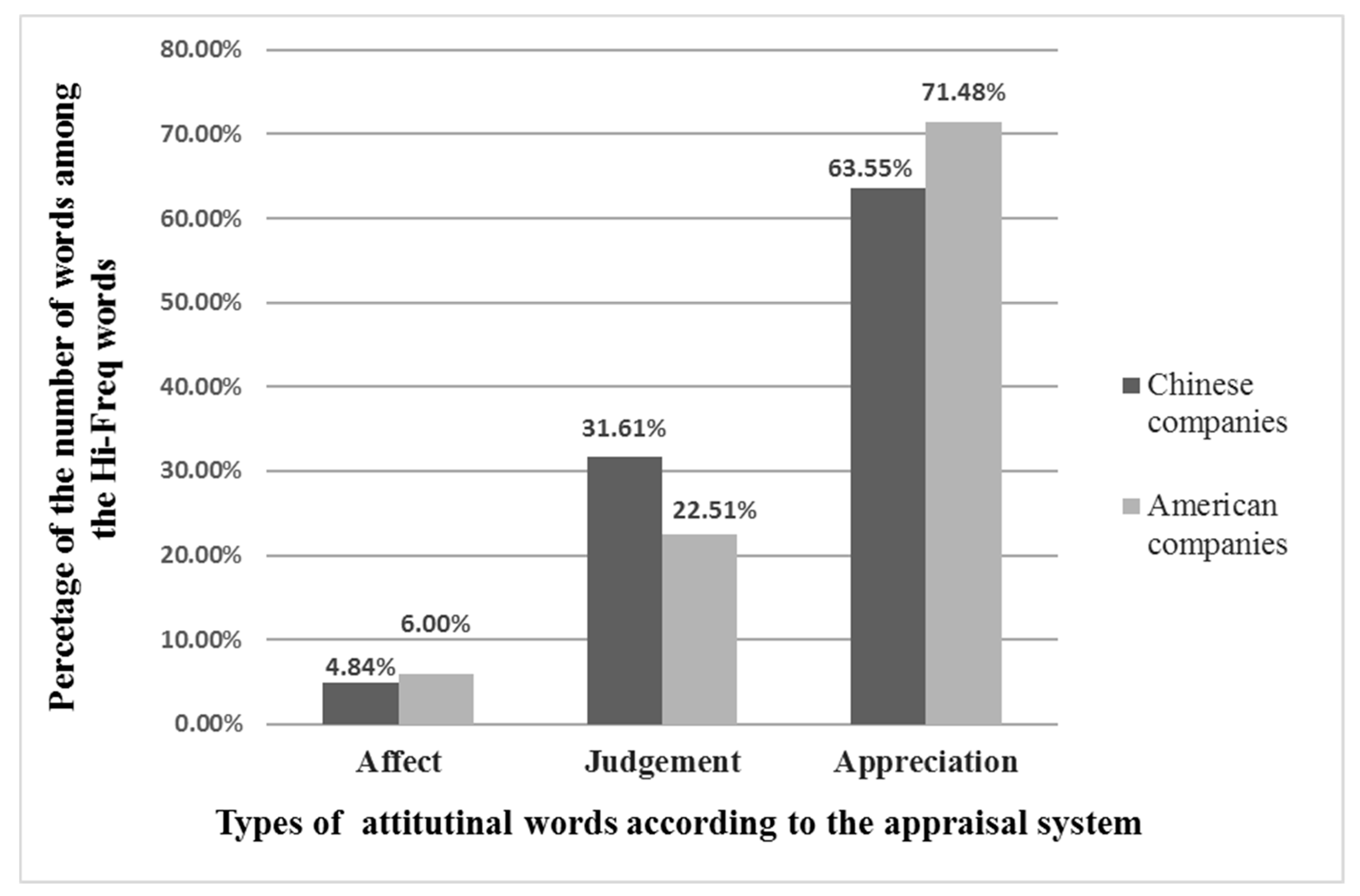

Based on

Table 1 above, we tallied the top 100 attitude evaluation words according to the three subsystems—affect, judgment, and appreciation. The results are presented in

Figure 2 below. From

Figure 2, we can see that in the mission statements of Chinese and American enterprises, the distribution of attitudinal resources among the three subsystems of the attitudinal systems are of a similar pattern. Both Chinese and American companies significantly emphasized appreciation meaning in their mission statements than they did the other two subsystems (in terms of words used, the Chinese and American companies had 63.55% and 71.48% words in this dimension, respectively), with the judgment words (31.61% and 22.51%, respectively) coming next, and affect words (4.84% and 6.00%, respectively) coming last. This pattern is interesting. We may attempt to interpret it as follows:

Among the three subsystems in the appraisal system, the affect subsystem is concerned about the physiological response and psychological feelings; it illuminates appraisal meaning from the subjective point of view; while the evaluation criteria of judgment and the appreciation system are from institutional and social points of views. The mission statement is not made by an individual, but by a company which is a formal organization. In order to gain organizational legitimacy [

35], and establish a stable and professional organizational image, the company will avoid using affection words which express subjective emotions in their formal documents such as mission statements. In order to obtain the recognition of internal and external stakeholders as well as organizational legitimacy, an enterprise will reference other enterprises’ mission statements in its own formulation of mission statement [

35,

36,

37] and use more judgment and appreciation resources that cater to social values. It is worth noting that on the dimension of “judgment”, the Chinese companies had a substantially higher percentage of words in this category as compared to the American companies: 31.61% vs 22.51% (in contrast to the patterns in the other two subsystems in which the American companies’ percentage are both higher compared with the Chinese companies, though very modestly higher in the affect subsystem). This phenomenon may be interpreted from the different cultural backgrounds of the Chinese and the American companies. While the US is a more individualistic society with tolerance being one of its hallmark characteristics, and thus much less judgmental toward entities (individuals and organizations), China is a society with a higher level of collectivism which exerts higher pressure or requirements for conformance [

7], thus entities (individuals and organizations) tend to be more judgmental and be more judged by other entities. We therefore saw the difference displayed between Chinese and American companies in their use of judgment words in mission statements.

In short, although the cultural and economic background of Chinese and American enterprises are different, the social functions of the corporate mission statements are more similar than they are different. Therefore, the Chinese and American enterprises show similar patterns in resources distribution among the three subsystems—affect, judgement, and appreciation. Yet, with the overall similarity, there is still visible cultural difference as manifested in the dimension of judgment. The more judgmental tendency of the Chinese companies might be a logical reflection of the overall social and cultural context in Chinese companies where the pursuit and maintenance of norms are more highly valued.

4.2. Similar Trend in the Frequency Change of Attitude Evaluation Words

From the high-frequency word list for the Chinese and American companies, a line chart of high-frequency attitude evaluation words can be drawn (

Figure 3). In

Figure 3, the horizontal axis shows the numbering of the 100 high-frequency words (from high-frequency word 1 to word 100, with the 1st having the highest frequency and the 100th having the lowest frequency), while the vertical axis is the corresponding frequency of each word.

Figure 3 below shows that high-frequency words in the Chinese and American companies’ mission statements have a similar pattern. Specifically, companies in the two countries displayed a steep pattern in the highest ten attitude evaluation words of their mission statements, while the rest of the words are located in the much flatter portion (or “tail”) of the curve. A small difference is that the top 27 high-frequency words of Chinese companies have a higher frequency than those of American companies, while the frequency of the remaining words appeared to be reversed: the remaining words of American companies had higher frequencies than their counterparts of the Chinese companies. This shows that the Chinese companies’ mission statements are more highly concentrated in using a few high-frequency words (with respect to the American companies, whose word use are relatively more evenly distributed).

Such a pattern reflects that both Chinese and American companies have their own shared focus contents respectively in mission statements. As for other contents, the relatively flat pattern indicates more diverse concerns among American companies, making a mission statement a showcase to communicate to the public for the American companies. This phenomenon may be viewed from the fact that the American companies have been more mature in their strategic management, that they more fully understand and therefore emphasize the importance of a mission statement’s guiding roles and impacts to their company, that their mission statements are the product of a deep, thorough, long-term “distillation” of their own business values and strategic pursuit, from their own business practices. In contrast, the Chinese companies are “late comers” in strategic management and in the use of a mission statement as a strategic management tool and mechanism, that the Chinese companies are still learning, often from outside and not so much from inside values, true beliefs, success and failure in business models and business practices (as compared to the American companies), and thus the high-frequency words in their mission statements are more a product of “textbook learning” or “adopting from model cases/benchmark companies” than “home-grown” characteristics, resulting in the higher level of resemblance of top key words in the Chinese companies and less variety and characters in words other than the top high-frequency words used by the Chinese companies.

4.3. Chinese Companies Place Emphasis on “Innovation” while American Companies Place Emphasis on “Customers”

Although the subject companies showed similar frequency patterns for the high-frequency words in their mission statements, the specific key contents were different in their mission statements. To illustrate in detail, we compiled

Table 2 for the top 5 high-frequency words to find what kind of contents were of upmost concern in Chinese and American companies, respectively. From

Table 2 below, the top 5 high-frequency words were totally different in the mission statements of Chinese and American companies. Over 50% of Chinese companies focus on “innovation”, “development” and “society”, while over 50% of American companies place emphasis on “customers”, “communities” and “services”, with a similar frequency distribution for these top high-frequency words as their counterparts. The number one word among Chinese companies is “innovation”, while “customers” is the highest-ranked word among American companies. Through such top words, we may draw an overall picture that Chinese companies are concerned about innovation and external environment factors such as societal and national development. American companies, on the other hand, pay more attention to customers and services that relate directly to business success, and corporate citizenship-related behaviors and goals such as community interaction and involvement.

One of the main reasons that resulted in the differences is China’s current economic environment and the policy leveraging roles of major enterprises. The widespread word “innovation” among the mission statements of Chinese companies was partly due to the national policy of innovation stimulation in China, whose market economy was established many decades behind developed countries. At the present stage, the Chinese government has been vigorously advocating “mass entrepreneurship and innovation” and held this policy as “an essential and necessary choice to cultivate new dynamics of economic and social development”. Therefore, “innovation” is reasonably becoming the main pursuit of Chinese companies at the current stage. This pursuit is, naturally, reflected in the mission statement of Chinese enterprises, and the purpose of “innovation” to achieve “social development” is also reflected in the statements. The high-frequency use of the two key words “innovation” and “create” are in line with the direction of innovation pursuance.

Furthermore, most of the Chinese enterprises on the sample list are state-owned enterprises; such ownership amplifies the societal function of those enterprises and their obligation to respond to the call of the state for innovation. The two high-frequency words of “country” and “society” are in line with this emphasis for Chinese enterprises, because of not only the government-compliant, government-responsive characteristics of Chinese companies, but also a mindset of long-term government-guided, ideologically charged organizational culture in China. They could reflect another subtle but understandable difference between Chinese and American companies: the American companies have been putting in action their social responsibilities and business values of social contribution through service to their communities, and therefore the word “community” is a natural reflection of what they believe and what they have been doing for yeas or even decades. In contrast, the Chinese companies are just “newly arriving” in the arena of more spontaneous involvement with the society, that there is still a clear impact of “response to government calls” in the form of such big words as “country” and “society”. To speak in an over-simplified way, the mission key words of “community” and “help” in American companies are the result of the American companies actually “doing” their social interaction work, and the mission key words of “country” and “society” (big words) in Chinese companies are the reflection of the Chinese companies “thinking” of their social interaction work, or even “showing efforts in compliance to government advocates”.

Another reason of the differences is that American companies have been operating in market economy for many, many decades, that they have developed a deeper understanding of the fundamental sources of corporate profits. They focused not only on such obvious factors as customers that affect the profitability of enterprises, but also on the fact that indirect factors such as community involvement and giving back are also related to the corporate image and long-term success of the company. The American cultural tradition of local autonomy (rather than government intervention) also drives the American enterprises in the direction of community interaction more than governmental (state) interaction as compared to their Chinese counterparts. Both factors play an important role in encouraging the American companies to pay much higher attention to customers, and to community in the context of a mature market in a civil society.

4.4. Common Emphasis on Survival, Corporate Philosophy and Public Image, but Significant Differences in Terms of Customer, Product or Service, and Market

The analysis of the high-frequency words above is in the perspective of linguistics, using the appraisal system. As a supplement to this perspective, we applied the nine key components theory [

11] to analyze the different concerns of Chinese and American companies on the composition of mission statements. The nine key components include: (1) Customers: who are the enterprise’s customers? (2) Product or service: what are the firm’s major products or services? (3) Markets: where does the firm compete? (4) Technology: what is the firm’s basic technology? (5) Concern for survival: what is the firm’s commitment to economic objectives? (6) Philosophy: what are the basic beliefs, values, aspirations and philosophical priorities of the firm? (7) Self-concept: what are the firm’s major strengths and competitive advantages? (8) Concern for public image: what are the firm’s public responsibilities and what image is desired? (9) Concern for employees: what is the firm’s attitude towards its employees? The nine key components theory provides an important and effective perspective for the analysis of mission statements; it is widely used in the study of mission statements. It is also considered a classic instrument to judge the quality of a mission statement.

We used David’s nine key components theory to categorize the high-frequency words, and counted the number of high-frequency words, total frequency of words in each component and the number of companies that mentioned each component. In order to test the significance of the difference between Chinese and American companies, we conducted the Pearson Chi-Square test on the number of companies that mentioned each component for each of the nine components. The results are shown in

Table 3 below:

From

Table 3, there are similarities and differences in the concerns for nine components between the subject enterprises of the two countries. On the word frequencies, both Chinese and American enterprises were highly focused on the concern for survival, philosophy, and concern for public image; but Chinese enterprises pay more attention to philosophy than American enterprises. It is mainly because Chinese enterprises have been immersed in strong Confucius culture for over a thousand years and hence the mission statements have reflections on that deeply ingrained cultural tradition. For example, Confucianism emphasizes “harmony” and “unity of heaven and man”, and some kinds of metaphysical laws, but is critical of human society’s function and development. This is reflected in the philosophy in the mission statements of Chinese enterprises. What is more: the practices of Chinese businesses in recent decades have been highly pragmatic, which created a tension with the pursuit of the traditional Confucianism culture, so that there is an urge for Chinese businesses to resolve the conflict by emphasizing philosophy in their mission statements. From the results of the Pearson Chi-Square test, we can see that significant differences existed between the enterprises of the two countries in terms of customer, product or service, and market, besides philosophy. American enterprises placed significantly more emphasis on these three components, which is thought-provoking and would be interesting to analyze.

We suggest that the above phenomenon has to do with the modern tradition and the current reality of government-dominated social governance in China as compared to the deep-rooted free market economy in the US. Firstly, most of the Chinese companies on the Fortune 500 list were state-owned enterprises, which naturally and logically demands that the Chinese companies pay more attention to their main owner—the government—with respect to customers or market. The American companies on the list, on the other hand, were almost all owned by private citizens (or a collection of private citizens) and operated in a mature free-market economy, which endowed them with better knowledge about the essential factors of a free market, with the customer being at the center and as the ultimate end of all efforts, products and services being the vehicles to deliver functions and values to customers and to satisfy the needs of customers, and market being the overarching mechanism to encompass the above. The command and practice of the above concepts and factors directly contribute to the success of the American enterprises. Therefore, the American firms place significantly more emphasis onto those factors. Secondly, Chinese enterprises have long been under a command economy, that they are still somewhat in a mindset to focus their attention to, or place higher value on, governmental plans and societal functions as related to the roles of the government. Besides, to the Chinese firms, it is still hard for them to fully tap into the market to the same extent as their American counterparts.

4.5. American Companies Pay More Attention to Stakeholders in Primary Social Stakeholders (PSS), while Chinese Companies Highlight Secondary Social Stakeholders (SSS)

To further capture the status of the sampled enterprises’ interaction with their internal and external stakeholders, we need to examine the mission statements from the perspective of stakeholder theory. We adopted Wheeler’s categorizing criteria of stakeholders [

16]. Wheeler divided stakeholders into two groups—Social Stakeholders and Non-Social Stakeholders based on social dimensions. The first group, Social Stakeholders, can be further divided into Primary Social Stakeholders (PSS), who are directly related to the company and directly involved human entities, and Secondary Social Stakeholders (SSS), who have indirect relationship with the company through social activities. The second group, Non-Social Stakeholders, can be further divided into Primary Non-Social Stakeholders (PNS), who impact directly on the companies but do not involve human relationships, and Secondary Non-Social Stakeholders (SNS), who have indirect influence on the companies without direct relationship with personnel. PSS include customers, employees and managers, investors, local communities, suppliers and other business partners. SSS include government and civil society, social and third-party pressure groups and unions, media and commentators, trade bodies, and competitors. PNS include the natural environment, non-human species, and future human generations. SNS include environmental pressure groups, animal welfare pressure groups, etc. Accordingly, we identified the high-frequency words in the mission statements and categorized them into four detailed groups as shown in

Table 4 below.

From

Table 4, Chinese companies have eight words that refer to stakeholders, accounting for 13.60% of the total frequency of top 100 words in mission statements; American companies have 11 words and a percentage of 16.91 correspondingly, suggesting more concerns on stakeholders than Chinese companies in general. It can also reflect that the American companies better identified their stakeholders than the Chinese companies, who are still in the relatively early stage of breaking away from government dominance and identifying and serving stakeholders other than the government and its delegating entities.

When it comes to the specific types of stakeholders, Chinese companies attach more importance to SSS, while American companies attach more importance to PSS. In terms of PSS, apart from the three stakeholders common to the companies of both countries (employees, customers, and shareholders), American companies take more entities such as communities, partners and suppliers into consideration. But Chinese companies have “talents” (the Chinese term for “valued, highly capable employees”) as PSS that are less frequently mentioned in mission statements of American companies. With the mention of “talents” added to the category of “employees” for the Chinese companies, we can see that the Chinese companies place substantially more emphasis on their employees. In terms of SSS, one significant difference is that Chinese companies place much more emphasis on “society” than American companies, which is consistent with the discussions in

Section 4.3. We attributed Chinese companies’ emphasis on “society” to the social-economic system in China and the nature of the companies studied resulted from their ownership. Most of these Chinese companies are state-owned enterprises, which were born with societal function, such as promoting governmental policy implementation and providing social welfare. Another difference is that environment (both natural and working environment), referring to PNS, is valued much more in American companies. Environmental protection is a concept and value pursuit that is yet to be instilled into and established among Chinese enterprises.

There is one phenomenon worthy of special attention, which is that the word “communities” was mentioned by over 50% of the American companies, but did not appear in the top 100 words of missions of Chinese companies—a sharp contrast. This deserves to be further discussed. The lack-of-value situation of communities in Chinese companies is mostly due to the immature relationship between companies and local communities [

38]. Specifically, first of all, the market mechanism in China was established in recent decades, and the enterprise–community relationship management was still mainly government oriented and government dominated, especially in long-term planning, with enterprises playing a passive role in community relationship management. In the context of the Chinese companies, “community” most of the time points to the relationship with local government and its branch institutions. Due to the nature of a government-dominated society, there would not be community if it were not for the local government. So, it is natural that the Chinese companies only see government rather than “community”. In the Chinese context, when the word “society” is mentioned, it often implies things/issues/initiatives by or related to governments of various levels, as opposed to “community” in the American context. In industrial countries (with US as being representative), social movements claimed by activist groups and the legislation and judiciary practices force and encourage enterprises to take part in corporate social change activities [

39] which refer to initiatives to improve social good and the well-being of communities at local and global levels [

40]. The Chinese enterprises did not have such external compliance as mandatory, and many would not place even marginal importance of “community” in their business strategy, and therefore would be less motivated in the related aspects. Thirdly and critically, the relationship between communities and businesses is circumscribed by the norms of civil society in Western countries that enterprises ought to be responsible for community affairs. However, in China, the concept of civil society is still fairly new and the related practice is not pervasive (or even somewhat on hold in recent years); thus, commitment to communities is not common in business practice among Chinese enterprises, resulting in a lack of expression in the mission statements for Chinese companies.

5. Conclusions and Implications

We conducted a quantitative study on the mission statements of Chinese and American companies by establishing a corpus of mission statements based on the appraisal system, which is a new attempt in mission statement studies compared to recent studies using common text analysis. Conclusions can be drawn in two aspects. Firstly, as an important form of language usage in business, the mission statements of enterprises in two countries showed a similar pattern in using attitudinal resources effect, judgement and appreciation, with the appreciation subsystem being the highest emphasized system and the affect subsystem being the lowest. However, a significant difference was found with the judgment subsystem, with the Chinese companies emphasizing more on the subsystem. Secondly, as an interpersonal communication tool, mission statements differed among companies of the two countries on policy response, business operation and stakeholder concern—issues that relate to strategic management. Consistent with previous studies [

41,

42], the mission statements of Chinese companies are society oriented and emphasize the social roles of an organization, showing corporate pertinence to a lesser extent, while American companies pay more attention to customers and partner relationships, which can be seen as the American companies’ market and individual orientation.

An effective mission statement plays important roles in both strategic planning and goals setting by guiding subsequent business activities and impelling short-term actions consistent with long-term interests [

43,

44]. Through improving statements from both linguistic (for better communication and expression) and strategic (for better contents and targeted issues) perspectives, the mission of an enterprise could be better accomplished.

Based on our findings, several managerial implications can be drawn for Chinese businesses regarding the identification and formulation of their mission statements:

- (1).

Chinese businesses should develop a mission statement that is closely related to business and management. Chinese enterprises have focused their missions on “innovation” and “development of the society”, which was to a significant extent what the governmental policy advocates rather than the mandate of the direct strategic needs of the enterprises. Chinese enterprises should take both national interests and self-development into consideration rather than a high emphasis on the former. With marketization speeding up in China, Chinese enterprises, especially state-owned ones, should be more market oriented in enterprise upgrade and transformation, which (the market-oriented transformation) should be correspondingly reflected in the mission statement since it is a window to demonstrate the image and strategic direction of the enterprise. Therefore, a mission statement should cover a comprehensive view of the issues of enterprise development and maintain the balance between the role of the enterprise as a social entity and an economic entity.

- (2).

Chinese businesses should enrich their mission statement, by thoroughly examining the critical issues facing their business, so that they truly sense and identify the needs and even mandates of their environment and stakeholders, rather than a few textbook terms or “classic” pursuits of a few benchmark companies. Mission statements distilled from the firm’s own history and culture and unique strategic position as well as unique strategic pursuits would shape and project the company’s characters, thus more effectively establish the corporate image and better convey the company’s values and pursuits to its stakeholders internally and externally.

- (3).

Chinese businesses should raise keen awareness of the need of customers and be devoted to providing high-quality products or services for customers, in contrast to responding to the calls and orders of the government. The care and concern for customers as reflected in the mission statements of the Chinese enterprises is the lowest of the nine elements in mission statements and is significantly lower than that of American enterprises. Apart from that, the components of market and product or service are also of low concern among Chinese enterprises in comparison to American enterprises. The phenomenon largely demonstrates the historical formation, footing, and impact of Chinese companies being the products of a command economy from the 1950s–1990s. As discussed in

Section 4.4, the factors of “customer”, “products and services”, and “market” are critical, individually and together, to the survival and success of a company in a free-market economy. For the Chinese companies to excel in the gradually established market economy in China, they must pay utmost attention to these three factors, and act accordingly.

- (4).

Chinese businesses should pay comprehensive attention to the role of stakeholders and put it into practice. An enterprise is an open system whose survival and development depends not only on the production/operation, and the management of internal stakeholders, but also largely on the interaction with external stakeholders. Overall, Chinese enterprises’ concern for stakeholders was not as inclusive and complete as that of their American counterparts. Specifically, when it comes to external stakeholders, Chinese companies still weigh heavily on government (“country” and “society”) rather than community. The Chinese enterprises need to enrich their mission statements in terms of stakeholders and put words into practice: attach importance to the interests of consumers, to serving the community, and to protecting the environment. Moreover, mission statement should be drafted closely to the business strategy of the enterprise, guiding and providing context for the formulation and implementation of strategy and the institutionalization of specific strategic initiatives [

45], such as sustainability or total quality management (TQM).