Abstract

Youths are the next generation to foster community resilience in social–ecological systems. Yet, we have limited evidence on how to engage them effectively in learning about environmental change. One opportunity includes the involvement of youths in research that connects them with older generations who can share their values, experiences, and knowledge related to change. In this community-based study, we designed, assessed, and shared insights from two intergenerational engagement and learning interventions that involved youths in different phases of research in the Saskatchewan River Delta, Canada. For Intervention 1, we involved students as researchers who conducted video and audio recorded interviews with adults, including Elders, during a local festival. For Intervention 2, we involved students as research participants who reflected on audio and video clips that represented data collected in Intervention 1. We found that Intervention 1 was more effective because it connected youths directly with older generations in methods that accommodated creativity for youths and leveraged technology. Engaging the youths as researchers appears to be more effective than involving them as research participants.

1. Introduction

Youths are the next generation of policy-makers, civil society leaders, and environmental stewards to assess and respond to environmental change in social–ecological systems. From now and into the future, youths will shape the potential for community resilience, which is conceptualized by Berkes and Ross [1] as an integration of efforts across societal levels that build capacity for communities to thrive in the context of environmental change. Engaging youths in learning about past experiences with living, adapting, and persisting through change is a key imperative for building community resilience, intergenerational equity, and sustainability for future generations [2,3,4]. However, synthetic and empirical studies alike have argued that we have defaulted largely to the engagement and learning needs of adult actors in resilience research and planning, and hence, contributed to a broader failure to consider how to cultivate youth leadership and stewardship skills, which are recognized as core strengths necessary for building community resilience [5,6,7,8].

One potential entry point is to involve youths in research that directly engages them in social contexts that support youths learning about environmental change and the leadership and stewardship behaviors needed to respond to change. However, a systematic review of youth involvement in community-based research indicates that there are “almost limitless” opportunities to draw on practices in communities to guide the prioritization of youths in research [9] (p. 186). This insight reflects the need to work with and for communities to better design and assess methodologies that prioritize youths.

Many Indigenous communities introduce youths to perceptions, values, and preferences held by multiple generations of people living in a community [10]. One author of this paper—a teacher in such a community—explains that this is a form of intergenerational engagement and learning necessary to understand well-being through mino-pimatisiwin, a Cree concept for teaching and learning about living a good life. Intergenerational engagement and learning practiced in this way can be crucial to many Indigenous communities who hold sustained connections to the land and water, who continue to experience and resist colonization, and for whom the erosion of social–ecological well-being is a key concern [11,12,13]. In a formative Canadian report, for example, Clarkson et al. [14] (p. 83) emphasized that:

The intergenerational transmission of knowledge is threatened by the increasing alienation of young people from their culture. The transfer of knowledge from one generation to another is also threatened by the increasing encroachment of western civilization...The involvement of Indigenous youth…in documenting the knowledge of traditional people will ensure that the information is both recorded and used to strengthen Indigenous societies.

Indigenous communities that prioritize youths in intergenerational engagement and learning pass down knowledge and values in a variety of ways. These can include stories and lessons about ideal behavior, spiritual and cosmological rituals and practices, and experiences resisting and persisting through colonization via different political and decision-making processes, including as self-governing nations [14,15]. Another author of this paper—a guidance counselor in an Indigenous community—states that prioritizing youths in such a way “is in our DNA”. Thus, advancing methodological processes capable of leveraging such contexts provides a dual opportunity: to support and honor ongoing efforts in Indigenous communities to engage youths intergenerationally, and to enrich theory for evidence-based insights that prioritize youths.

In this article, a collaborative research team of leaders at a community school and university researchers developed, assessed, and shared insights from a methodological process that prioritized youths in environmental change research. We undertook this work in a First Nations and Métis community, Cumberland House, in the Saskatchewan River Delta, Canada. Our first objective was to create meaningful engagement for youths in two intergenerational interventions in different phases of research. In Intervention 1, we involved youths as researchers, responsible for collecting data from interviews with adults and Elders during a five-day local festival. In Intervention 2, we involved youths as research participants, as they reflected on key themes from data collected in Intervention 1. Our second objective was to evaluate those interventions for their learning outcomes as indicated by short-term behavioral changes and estimates for the potential of long-term behavioral change. Our third objective was to reflect on the contextual factors that shaped those outcomes to develop evidenced-based lessons about prioritizing youths for community resilience.

2. Conceptual Framework

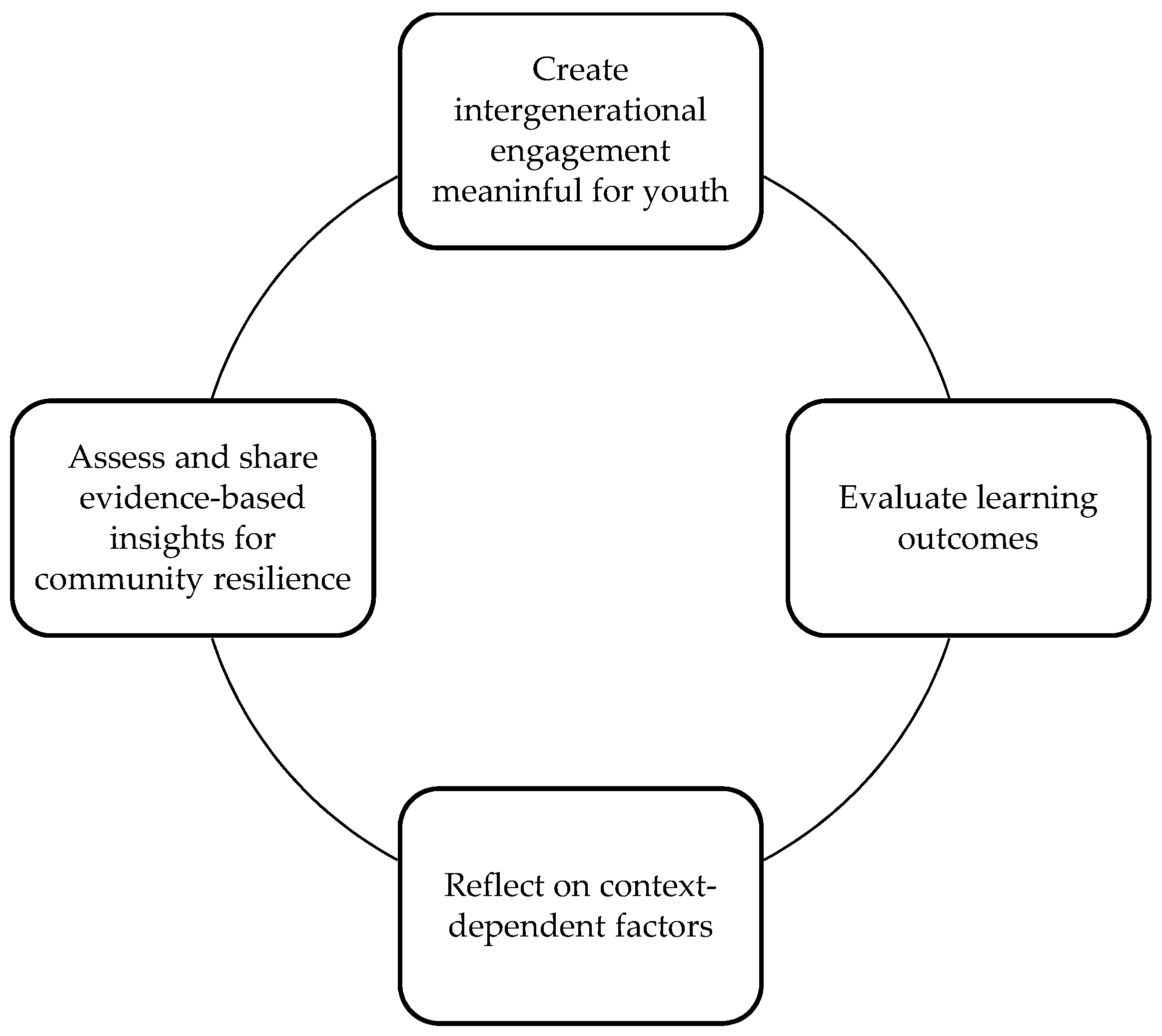

Our conceptual framework guided the design and assessment of our methodological process to prioritize youth engagement and learning about environmental change in intergenerational contexts (see Figure 1). Following this framework, we undertook our research in four stages: 1. Create intergenerational engagement meaningful for youths; 2. Evaluate learning outcomes for youths at individual and group levels; 3. Reflect on the context-dependent factors that shape the outcomes; and 4. Assess and share evidence-based insights for community resilience.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

2.1. Create Intergenerational Engagement That Is Meaningful for Youths

To create intergenerational engagement that was meaningful for youths we applied the concept of community resilience. Our community-based research partners identified community resilience as a compelling practical focus for pursuing the conceptual framework. Community resilience integrates two strands of resilience literatures that theorize how to draw from existing engagement in community settings to build learning outcomes at multiple levels [1]. From education, health, and psychological literature, community resilience emphasizes using practices and programs that promote psychological and cultural well-being in community settings that develop ‘resilient’ individuals [16,17]. From environmental change studies, community resilience is about translating and extending the benefits of engagement to groups and entire communities in a research context [2,18]. Together, these strands form a compelling place-based, community driven conceptualization for creating intergenerational engagement that is meaningful for youths.

One challenge in the existing literature on community resilience is the focus on the individual, as opposed to the social context in which the individual is embedded. Education, health and psychological theories provide an entry point for fostering resilience for individual youths by leveraging ongoing practices and programs that connect youths with older generations. Environmental change and sustainability studies theorize how to extend benefits to groups of youths and place-based communities, for example, through a research context that can produce evidence-based insights. However, we know more about the practices and programs that support individual benefits for youths, and less about how to formalize and extend those benefits across societal levels. For example, research in Indigenous community settings recommends that meaningful engagement can be fostered in opportunities for youths to adapt and be creative with the support of social networks comprised of friends, family members, neighbors, and community leaders, such as teachers and Elders [19,20]. Yet, the extent to which aspects associated with meaningful engagement can produce multi-leveled learning requires further evaluation.

2.2. Evaluate Learning Outcomes

A systematic review of the effectiveness of intergenerational engagement programming [21] and a meta-analysis of outcomes from engagement and learning in classrooms [22] identified two challenges for evaluating learning outcomes. First, evaluations are often designed to assess intellectual development (i.e., what youths learn), as for example with testing, without attention to the psychosocial processes that underpin learning (i.e., the emotional and value-laden exchanges that shape how youths learn), such as estimating behavioral outcomes during the exchanges between youths and older generations [23]. Second, interventions often do not include the appropriate methods to foster and observe behavioral change that indicate learning. Two examples of appropriate methods include the use of technology to foster behavioral change, and including in the evaluation key people, such as teachers and community leaders, who hold enough familiarity with participants to observe or estimate behavioral outcomes [22,23].

Several opinion papers and empirical studies related to resilience and environmental change have recognized the need to overcome both behavioral limitations [24,25,26]. Recent empirical research involves new approaches for engagement and learning that support psychosocial exchanges, including the sharing of mental models of change, involvement of emotional responses in participants, and the steering of changes in participant preferences and values. Some examples include the use of art exhibits [27,28], animations [29], and participatory theater [30,31]. These examples point to the considerable opportunities that exist to enrich resilience theory by involving methods and research partners capable of assessing the psychosocial nature of learning outcomes at multiple levels. However, due to the difficulty of evaluating outcomes that occur in social contexts often unfamiliar to scientists, there is a need for reflexive research.

2.3. Reflect on Context-Dependent Factors

‘Reflexive research practice’ refers to critical reflection throughout the research process that helps “sensitize the researchers to the cultural, social, political, and economic contexts of the research and to acknowledge multiple possible interpretations of the findings” [32] (p. 547). Synthetic research on intergenerational engagement and learning programs have indicated that communication of those reflections added rigor and validity to findings, and by extension, have helped to mobilize factors that are context-dependent into insights that are context-sensitive [33,34]. The outcomes of reflexivity are, therefore, important for prioritizing youths in environmental change research, with and for communities, where researchers including youths are able to contribute to an understanding of how context has shaped engagement and learning [35]. In their research prioritizing youths in research about coastal fisheries change in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada Power et al. [36] recommend that such reflexivity is necessary for explicit development of shared practices and ways of speaking about change across generations to provide “a strategy to deal with, and indeed heal, the damaging impact” of change.

Despite its necessity for evidence-based programs, context-sensitivity is underappreciated in relation to statistical generalizations as argued in decades of empirical research in a range of fields such as the policy sciences [37], critical feminist human geography [38], social anthropology [39], inter- and trans-disciplinary research [40], and Indigenous scholarship [41]. In resilience research, reflexivity has been operationalized in community-based research designs, which has enriched empirical findings in those designs, according to synthetic studies on resilience methodologies [42,43]. Community-based research often features trust-building and power sharing among all involved to ensure that research expectations are exchanged, and research meets the goals of communities. The goal has been to develop research salient for communities, and evidence that is credible and legitimate from the standpoints of multiple knowledge systems, including western sciences and theories, as well as Indigenous knowledges and practices [1,2,44].

2.4. Assess and Share Evidence-Based Insights for Prioritizing Youths

The final stage in our process of designing and assessing a methodological approach to prioritize youth engagement and learning was to look to the literature for insight on how to empirically capture youth engagement interventions and outcomes. We used Reimer et al.’s [45] conceptual model to assess youth engagement interventions and Mezirow’s [46] transformative learning theory to assess learning outcomes (see Table 1). Reimer et al.’s model emphasizes examination of the structure of interventions and engagement processes that prioritize youths, the outcomes youths experience from those interventions, and the contextual factors that shaped those outcomes. This model has been used to measure a variety of outcomes, but not always learning (cf. [47,48,49,50,51]). We used Mezirow’s theory to assess learning outcomes. Mezirow argues that learning occurs at different depths of meaning, where deeper learning is understood as transformative, as defined in Table 1 [46,52,53]. Together, Reimer et al.’s model and Mezirow’s theory guided the assessment of our interventions, outcomes, and factors related to our three objectives. Addressing each of these objectives contributes to gaps in resilience theory.

Table 1.

Youth engagement and learning model adapted from Reimer et al. [45] and Mezirow [46].

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area

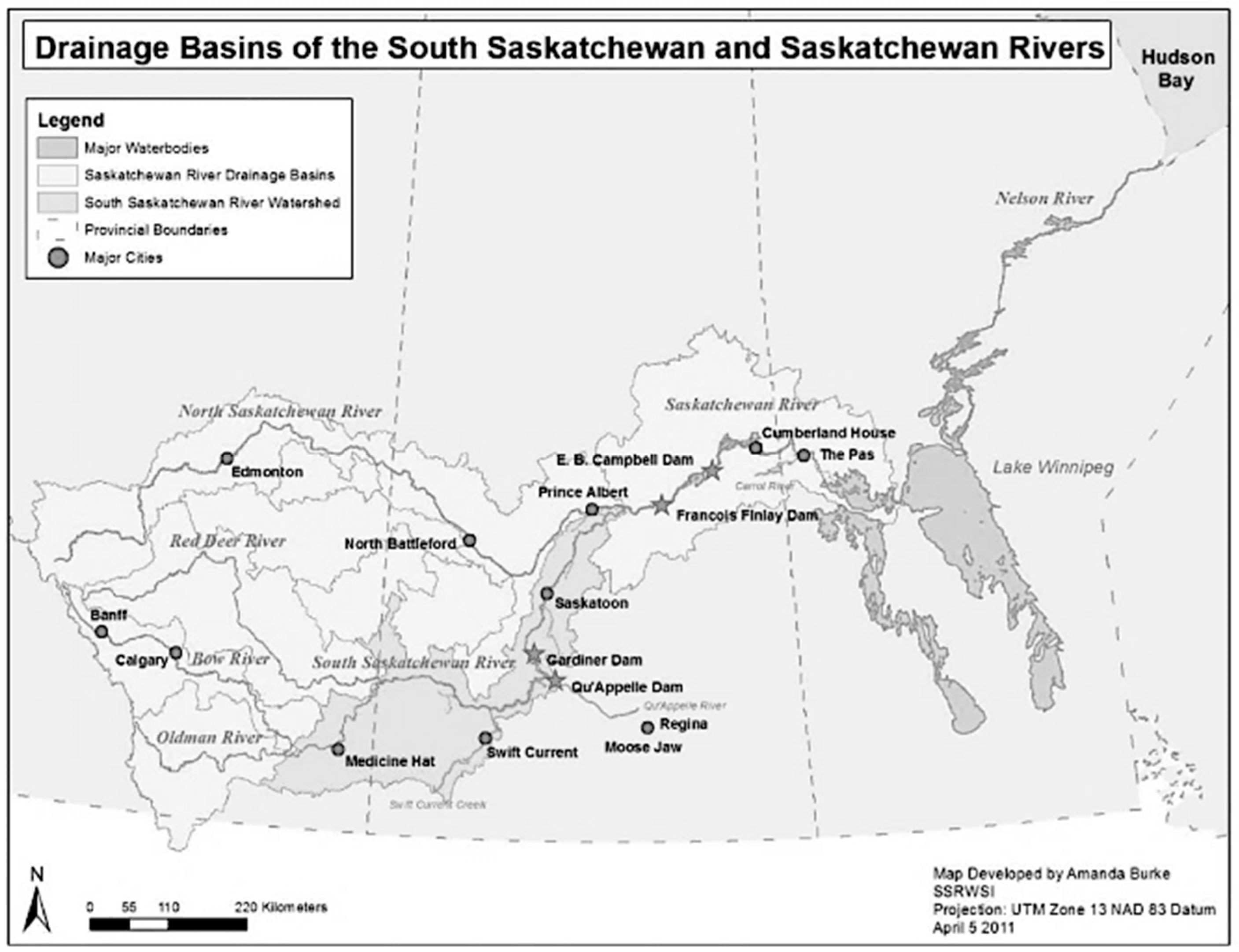

Our research was undertaken in Cumberland House, in the Saskatchewan River Delta, Canada (Figure 2). The Saskatchewan River Delta is the largest inland delta system in North America. This delta system has provided rich wetland-dependent flora and fauna, which has driven human settlement and interaction since time immemorial. Cumberland House is considered the first settlement in Western Canada, and now consists of two administratively separate communities with predominantly Cree and Métis populations: the Northern Village of Cumberland House and Cumberland House Cree Nation [54].

Figure 2.

Drainage basins of the South and North Saskatchewan Rivers, with hydroelectric dams shown, with permission from the South Saskatchewan River Stewards 2015.

Since settlement, the impacts of hydro-development on the delta system have produced adverse changes to community health and well-being [55,56]. A point of contention for delta residents is the hydropeaking function of the E.B. Campbell Dam, established in 1963, and located 100 km upstream from the two Cumberland House communities. Hydropeaking refers to the fluctuation of downstream water availability caused by the rapid increase or decrease in the release of water from hydroelectric dams in response to varying power demand. The Cumberland House communities have associated the E.B. Campbell Dam with declining fish and wildlife abundances and harvest rates, reducing access to lands and waterways, and formerly-abundant species, as well as barriers to transmitting cultural knowledge about the environment to future generations [56,57,58]. In addition, other drivers of change, such as climate change, have also adversely affected traditional subsistence activities by altering the abundance and range of different species, and therefore reducing access to traditional hunting and trapping grounds [56,57,58], This has reduced intergenerational transfer knowledge by limiting the opportunities for older generations to teach younger generations about the delta during hunting and trapping [58]. These losses, combined with the removal of children to residential schools, have resulted in large generational knowledge gaps [14]. These drivers of change have reduced opportunities for youths to experience and observe and learn from the delta with family and fellow community members [58].

In the midst of rapid social–ecological change, youths in the delta have been learning from previous generations about post-settlement changes to the land and water in both western and land-based education contexts. The Charlebois Community School encourages Cree language programs, land-based practices and education, and school curricula to address the declining graduation, numeracy, and literacy rates, as well as the gradual erasure of Cree language capacities and identity in younger generations [22]. Often, for example, school leaders bring Elders into classrooms to teach lessons about the delta or about traditional subsistence and cultural activities, and to deliver Cree language programs. In the summer months, school and other community leaders hold culture camps, where youths of all ages participate in activities such as tanning hides, cooking traditional meals, and doing artwork. In addition, the school has developed the Environmental Classroom, a pilot project for Grade 10 students that teaches delta knowledge and western science curricula in and outside of the classroom (e.g., field trips in the delta). In addition, intergenerational engagement and learning is shaped by an explicit set of community values known as the Circle of Courage. The Circle of Courage Model is based on the Medicine Wheel, a symbol relevant to Southern Plains First Nations [59,60]. It incorporates the idea that harmony needs to be restored in youths through four essential human values: belonging, mastery, independence, and generosity. The use of the Circle of Courage is an example of context-dependent practice that shapes youth experiences in intergenerational engagement and learning.

3.2. Community-Based Research Approach

We adopted a community-based research approach in which leaders from the Charlebois Community School and researchers from the University of Saskatchewan co-designed, evaluated and reflected on the research process. This research was community-driven. School leaders indicated to university researchers that they wanted to engage students in research about the changes occurring in the Saskatchewan River Delta. Moreover, school leaders identified that they wanted the research to leverage an intergenerational engagement and learning context: a five-day local festival celebrating 125 years of education in the community, known as “Coming Home”. Many current and former residents would be attending and there would be a classroom module that showed audio and video clips from the festival. Thus, we developed our interventions to match these needs: one in which students collected audio and video interview data during the festival and the other in which students in the classroom would reflect on audio and video clips of quotations from adults, illustrating themes in the data.

Throughout the research process, we built trust by meeting multiple times to co-design the research process. We also agreed on how to share resources and on who controlled key aspects of the research. All research team members created materials and methods, and participated in the communication of the findings at various conferences and meetings. Data were housed and owned by the Charlebois Community School. Each school leader recruited and helped retain students for the research, provided feedback on interpretations of student experiences, and verified learning outcomes by reflecting on research results in relation to decades-long experiences of observing learning at the Charlebois Community School. University researchers secured ethics clearance and led preliminary analyses. Our research protocol and manuscript were formally approved by the Charlebois Community School. We conducted the research in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and its protocol was approved in 2015 from the University of Saskatchewan Research Ethics Board.

3.3. Participants

Youths in this research were defined as middle adolescent students from grades 7 to 11. Adult participants included current or former residents and Elders of Cumberland House communities, and encompassed harvesters, service sector employees, community leaders, and teachers; participants also included non-resident participants with knowledge of the Saskatchewan River Delta, including politicians and academics. Although Indigenous communities and First Nations hold different definitions, ‘Elders’ typically reflect a subcategory of adult participants with special designation by the community as local knowledge holders, keepers, and teachers. All participants gave their informed consent.

3.4. Interventions

Intervention 1 involved youths as researchers who collected audio and video data and took photographs during the Coming Home festival. We decided to involve a small number of youths (n = 10) to support individual learning and to match with our capacity to create structured opportunities for their leadership during the intervention. We provided the youths with an iPad to conduct the interviews, and a preliminary interview guide. Also, we trained them in securing informed consent. Youths worked in pairs to determine their data collection approach. They decided how they recruited adult interviewees, how they conducted the interviews including how and when they asked additional questions and probes, and from which parts of the festival they collected data. We gave notice to adults during the festival about the data collection. After each day of the festival, youths and researchers met to discuss the engagement and learning experiences.

Intervention 2 involved youths as research participants who reflected on the data themes from Intervention 1. We involved a large number of youths (n = 62) across three one-hour long classes to try to extend the benefits of data collection from Intervention 1 and assess the potential of group-level data to inform future learning interventions. For the reflection exercise, researchers chose audio and video clips with quotations by adult participants that best represented those themes and subthemes. We presented short thematic films back to youths, each film included a heterogeneous range of subthemes identified in the dataset. For example, one major theme was ‘priorities for youth stewardship’. We showed a video and audio clips in which adults spoke about diverse pathways for stewardship for youths to ‘be advocates’, ‘take local action’, ‘be concerned about water levels’, ‘be concerned about pollution’, ‘respect nature’, and ‘get to know the delta’. Youths responded to a qualitative questionnaire that included structured and open responses. Youths indicated whether they agreed that information in each subtheme reflected their thinking (e.g., ‘this is how I think’, ‘this is not how I think’, or ‘I do not know’). The intention was that the data would then inform teachers of key areas where future teaching could take place.

3.5. Analyses

Our research involved two levels of analyses. The first related to data collected by youths in Intervention 1 and was presented back to youths for Intervention 2. For Intervention 1, university researchers transcribed, coded and analyzed data using QSR NVivo 10 qualitative data analysis software. Coding and analysis followed a hybrid approach (i.e., top-down, bottom-up) to identify major themes and subthemes. School leaders verified the analysis. For Intervention 2, university researchers analyzed questionnaires using basic summary statistics to draw out themes related to group-level learning. The second analysis involved evaluation of interventions, learning outcomes, and context-dependent factors that shaped outcomes using Reimer et al. [45] and Mezirow [46]. During the implementation of both interventions, university researchers and school leaders were on hand to observe the youth engagement. We met during and after the ‘Coming Home’ festival to discuss observations. Those observations informed the application of Reimer et al. [45] and Mezirow [46]. A final evaluation using the variables and key indicators was circulated and consensus was reached, including about estimations of learning outcomes by discussing behavioral changes. We used our perceptions about the association among variables to guide the assessment and its verification (e.g., [44]).

4. Results

4.1. Create Intergenerational Engagement That Is Meaningful for Youths

Our first objective was to create meaningful engagement for youths in two intergenerational interventions in different phases of research. We applied Reimer et al. [46] to assess the structure and quality of the intervention, and the process of engagement by its intensity, duration, and breadth.

In Intervention 1, youths engaged directly with participants. Engagement required students to work eight hours a day for the duration of the five-day festival. Each morning, youths met with all research team members to prepare for data collection. Throughout the five days, youths conducted 59 interviews and took hundreds of photographs. Analysis of these data revealed four themes related to learning about and responding to environmental change—‘the meaning of the delta’, ‘delta health indicators’, ‘priorities for youth stewardship’, and ‘learning preferences’ (see Table 2). Subthemes indicated diverse perspectives about each theme. For example, the subthemes in ‘delta health indicators’, reflected four different place-based indicators for assessing environmental change in the delta system. In ‘priorities for stewardship’, the subthemes resembled six different entry points of action for addressing social–ecological change.

Table 2.

Key themes and subthemes about environmental change.

During the collection of these data, youth researchers received high levels of social support from research team members and from a large network of adult participants including family, friends, neighbors, and mentors, who were keen to help the youths complete their interviews. We assessed engagement as high in intensity (i.e., eight hours a day), breadth (i.e., range of themes about change and participants in different activities), and duration (i.e., five days) [45]. As a consequence, we evaluated this activity as a meaningful approach for creating opportunities for intergenerational engagement and learning.

Intervention 2 involved indirect engagement during which youths observed video and audio clips that illustrated the themes and subthemes related to assessing and addressing environmental change in the delta and answered the questionnaire. The activity took approximately one hour to complete for each of the three classes. There were high levels of social support but with a smaller network involving school leaders helping lead the activity. For example, the activity began with values-priming, led by Ingrid MacColl, Charlebois Community School Career Transitions Teacher, who described the Circle of Courage values and its importance in the community. In addition, we guided youths through the reflection activity. There were no opportunities for youth leadership. While the duration of the activity was low (i.e., one hour), the breadth was high, as the youths were exposed to many different perspectives illustrated in the video and audio clips. Most youths appeared to be engaged (i.e., watching videos and responding coherently), although some lost focus and stopped reflecting. As a result, we estimated that the meaningfulness of the intervention was moderate to low.

4.2. Evaluate Learning Outcomes

Our second objective was to evaluate our interventions for their learning outcomes. We used Mezirow [46] to assess learning outcomes at different depths. As such, we observed youths for behavioral changes that indicated instrumental, communicative and transformative outcomes at the individual-level and estimated learning outcomes at the group-level.

Intervention 1 yielded communicative outcomes at the individual level for youths as they collected data. Youth researchers interviewed adults with different perspectives, including different perceptions of change, values related to the delta, and preferences for action. The exchange of perceptions, values, and preferences are key to communicative learning [46,52]. Youths illustrated short-term behavioral changes by altering their interview approaches. In almost all interviews, youths deviated from the interview schedule by asking their own questions about livelihoods and lifeways in the past, and accelerated recruitment. We argued this represented key learning outcome as evidenced by youths changing research strategies that resembled building courage, creativity and comfort. We assessed it as communicative learning outcomes, as youths considered the diverse normative ideas that participants were sharing with them, such as what the delta meant to them or how to move to action in their own lives. While we suspected that these communicative outcomes produced diverse learning outcomes at the group-level, our approach to verification (i.e., debriefing at the end of the day through photos and written reflections) yielded too small of a dataset for assessment.

For Intervention 2, we estimated that some individual youths experienced both instrumental and communicative outcomes during reflections on sample quotations and in open responses, but at the group level some instrumental outcomes were apparent. For example, about half of the youths indicated that they wanted to learn more about the changes in the delta. We then asked the youths what they wanted to learn more about. Responses included learning what life in the delta was like “back then” in the time of their parents and Elders, and wanting to learn more about water quality, wildlife, water quantity, and plants. These responses indicated that youths were likely interested in the experiences and intentions of participants experiencing environmental change. The rest of the students were almost evenly split between responding negatively (29%), responding “I don’t know” or not responding at all (27%). This pattern was generally the same across all age levels. Students who responded negatively often said that did not want to learn more about the delta or felt that they already knew enough.

4.3. Reflect on Context-Dependent Factors

Our third objective was to reflect on the context-dependent factors that shaped learning outcomes. To guide reflections, we used Reimer et al. [45] to assess factors that initiated, moderated or hindered, and sustained outcomes across societal levels and into the future.

Two initiating factors supported learning outcomes activities: an explicit community values suite via the Circle of Courage, and previous intergenerational engagement through land-based education in the delta. Community team members indicated that the Circle of Courage model sets the stage for students to connect with older generations through reward mechanisms that incorporate values desirable in younger generations. In Intervention 1, the ‘Coming Home’ festival provided an ideal setting to support ongoing intergenerational engagement and learning with explicit representation of Circle of Courage values, such as through an awards ceremony, ‘the Circle of Courage Awards’. The classroom setting for Intervention 2 at the Charlebois Community School involved references and reminders to ongoing intergenerational engagement and learning and in particular, the Circle of Courage values.

Several moderating factors influenced the appropriateness of the interventions. In Intervention 1, there appeared to be excitement by youths to participate as researchers in this activity. This was evident in the large number and quality of interviews completed by youths and the learning outcomes observed. Importantly, active use of technology (i.e., using iPads to collect data) seemed to encourage interest from youth researchers. In addition, there was a willingness and generosity for adult participants to share knowledge. In Intervention 2, the Circle of Courage primer provided familiarity with concepts in the questionnaire. Passive use of technology (i.e., videos and audio clips) seemed to play a role in keeping youths interested, but to a lesser extent than in Intervention 1.

In Intervention 1, two hindering factors were apparent. While youths illustrated considerable interest and courage as researchers, they expressed some fear and anxiety over approaching potential participants and conducting interviews. As is the case with interviewing in other contexts, fear and anxiety could have hindered saliency, and promoted maladaptive strategies (e.g., one youth researcher declined to complete the week). For some, however, these challenges promoted adaptive strategies in the research (e.g., working in pairs, having preliminary conversations with potential participants). Due to the high intensity, breadth and duration of engagement, reflections on learning at the end of the day were difficult to develop for both the youths and research team members. While youths selected their favorite photos and interviews, it was challenging to elicit learning outcomes about those selections. In Intervention 2, some youths were unwilling to participate, and others lost focus. This was likely due to the everyday challenges of keeping youths engaged in the classroom setting and the indirect engagement through video and audio clips, as opposed to directly with participants.

Both interventions included sustaining factors. For Intervention 1, youths received a certification of participation, remuneration, and positive recommendations for their resume portfolios. Several months later, those youths presented their research for residents from three Canadian inland deltas at a three-day conference, Delta Days, sponsored by the University of Saskatchewan. For Intervention 2, results from the questionnaire yielded thematic guidance to direct further engagement and learning in the Saskatchewan River Delta. For example, we learned which themes about environmental change youths were more comfortable with, such as perceiving the delta as meaningful because it is a place to provide healthy lifestyles for its human residents. Moreover, we learned which themes illustrated gaps in thinking for youths, including using plants and animals as indicators for the health of the delta.

Opportunities to extend learning and steer long-term behavioral changes based on familiarity with themes and gaps in knowledge can be leveraged in preferred pathways for stewardship. For example, concern over water levels and pollution and the need for respect for nature seemed to resonate with youths. However, pathways such as “to advocate, take action, and get to know the delta” seemed to resonate to a lesser extent. Lastly, reflections on the data yielded in Intervention 2 indicates how youths preferred to learn. This scan confirmed an important role for relationships in guiding intergenerational engagement and learning on the land, a key practice for mino-pimatisiwin, although most youths did not know whether experiential learning resonated with them. Through locally-developed curricula, then, preferred learning pathways can help to strengthen diverse knowledge of environmental change in the delta and emphasize broader comfortability with action-oriented stewardship, a desirable long-term behavior for school leaders in this research.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Connecting youths with older generations who have lived, adapted, and persisted through environmental change is critical for building community resilience [1,2]. As indicated by practices in many Indigenous communities, intergenerational engagement and learning is a promising context in which to involve youths [10,11,12,13]. In western theory, intergenerational engagement and learning for youths is supported in principle, but there are limited examples and lessons on its formalization for environmental change and therefore opportunities to leverage place-based practice [5,6,17,18]. Our approach was to co-design and assess a methodological process to prioritize youths in environmental change research that was community-driven. Table 3 summarizes the results of the assessment, and the remaining discussion highlights key contributions related to our three objectives.

Table 3.

Summary of Evaluation of Intervention 1 and Intervention 2.

5.1. Create Intergenerational Engagement That Is Meaningful for Youths

The twin theoretical foundations of community resilience tell us that there are opportunities to draw on place-based practices to meaningfully involve youths and to extend those context-dependent benefits across societal levels and into the future. Research that leveraged Indigenous practice emphasized design principles that included supportive networks, experimentation, and creativity [19,20]. A comparison of the structure and quality in the interventions suggested that these aspects mattered considerably. Intervention 1 involved an engagement structure and quality of process more meaningful for youths than in Intervention 2. This was due to direct engagement of youths with adults and Elders, along with opportunities for youth leadership nested in large supportive networks. Furthermore, we associated the high intensity, breadth and duration of Intervention 1 with meaningful engagement, where the intensity and duration of Intervention 2 may have been too moderate and low, respectively, to foster significant interest in the breadth of perspectives.

5.2. Evaluate Learning Outcomes

The literature on intergenerational engagement and learning describes a key role for psychosocial experiences that manifest learning outcomes, but design limitations in interventions often do not manifest those experiences or include methods to observe their influence on behavior [22,23]. For Intervention 1, the structure and processes of engagement supported psychosocial experiences by allowing flexibility for youths and opportunities for two-way exchange with interviewees. Additionally, school leaders involved had enough familiarity to appropriately observe behavioral changes. We associated these conditions with the deeper learning outcomes in Intervention 1. For Intervention 2, we included the appropriate people to evaluate behavioral changes but not the social context necessary to foster them. As a result, learning outcomes were largely constrained to instrumental depths for groups of students. Youths did not exhibit the overwhelming positive behavioral changes researchers associated with communicative learning. In other words, it was not enough to engage youths indirectly with new knowledge and diverse values to produce observable behavioral change: youths needed to be in a social context that allowed for the exchange of psychological elements. For community resilience, this insight points to the important role of research partners and evaluation capable of manifesting and observing psychosocial experiences in youths.

5.3. Reflect on Context-Dependent Factors

Our research revealed that prioritizing youths in environmental change research relies heavily on the contextual factors in which it occurs. For Intervention 1, the active use of technology and the excitement and support from large social networks of generous and interested adults seemed to help youth researchers overcome initial fears, which we estimated fostered the communicative learning outcomes in our study. Yet, contextual factors revealed a trade-off between the potential to involve large numbers of youths and resources needed to do so. In Intervention 1, meaningful engagement and communicative learning outcomes arose from a large and flexible social structure, high quality processes, and resource-intensive contextual factors (i.e., technology and incentives). It would likely not have been possible in an experiential research context to recreate these aspects for large numbers of youths. To avoid this trade-off, methodological processes could leverage other examples in environmental research including those mentioned in this study that used art exhibits [27,28], animations [20], and participatory drama [30,31].

5.4. Assess and Share Evidence-Based Insights

This research developed and assessed a methodological process that prioritized youths in environmental change research. Following our conceptual framework, we argued that meaningful engagement and learning outcomes would manifest from two interventions (i.e., youths as researchers and youths as research participants) that leveraged intergenerational contexts in the Saskatchewan River Delta. Our assessment identified meaningful engagement and learning outcomes in Intervention 1 to a greater extent than in Intervention 2. Intervention 1 engaged youths directly with adults and Elders, with active use of technology in a large social network that accommodated opportunities for youth leadership and creativity. As a result, the structure and quality of Intervention 1, along with the key role of contextual factors fostered communicative learning outcomes. Thus, in Intervention 1 we provide a novel example of design principles for prioritizing youths in environmental change research informed by Indigenous practice and western resilience theory. In addition to these design principles, other evidence-based insights contributed to examples on how to prioritize youths for community resilience.

The application of Mezirow’s [46] theory revealed opportunities to be more strategic about verifying transformative learning outcomes, specifically, and learning outcomes at group-levels, more generally. For both interventions, verification of transformative learning outcomes was likely far beyond the temporal scope of this research, although unlikely with the design of Intervention 2. Furthermore, we were not able to verify group-level learning outcomes in Intervention 1, and group level learning was limited to instrumental depths and extended to all students. Taken together, further research is needed on methodologies that foster, observe and level-up transformative learning for youths in research and programs for community resilience.

As indicated by some scholars working with notions of resilience, including community resilience [2,42,43], critical reflection and reflexivity was critical for the development of interventions and findings in our community-based research. We involved youths in research salient for a community while at the same time drawing from Indigenous practice and resilience theory to formalizing and contextualizing evidence-based design principles for prioritizing youths in environmental change research. Achieving a balance between community goals and theoretical goals in this research can be attributed to the community team members’ insights and ongoing efforts to encourage the university team members to think more critically about the need to link Indigenous practice explicitly to resilience theory. The results of this balance revealed rich and diverse themes about environmental change. Reflections on these themes and the methodology and interventions from which they were derived helped formulate a locally-developed course that can build on how youths think and prefer to learn about environmental change. Moreover, the results helped to create opportunities to expand youth knowledge and learning preferences about change with different community perspectives, ways of observing, knowing, and learning about environmental change.

Author Contributions

The following contributions were made by the authors: conceptualization, E.J.A., K.S., L.M.-C., I.M., R.C., M.G.R., and T.A.S.; methodology, E.A., K.S., L.M.-C., I.M., R.C., and T.S; validation, L.M.-C., I.M., and R.C.; formal analysis, E.J.A., and K.S.; investigation, E.J.A., and K.S.; resources, T.A.S., and L.M.-C.; data curation, L.M.-C., I.M., R.C., and T.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.J.A.; writing—review and editing, E.J.A., K.S., M.G.R., R.C., I.M., L.M.-C., J.F.-B., and T.A.S.; supervision, L.M.-C., and T.A.S.; project administration, K.S.; funding acquisition, M.G.R., J.F.-B., L.M.-C., and T.A.S.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), grant number 415837.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the youth researchers and school leaders from the Charlebois Community School and other participants in this research from the Northern Village of Cumberland House and the Cumberland House Cree Nation, Saskatchewan, Canada. We wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, and Graham Strickert for early guidance on methodology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Berkes, F.; Ross, H. Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2012, 26, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, H.; Berkes, F. Research approaches for understanding, enhancing, and monitoring community resilience. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2014, 27, 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, D.; Reynolds, E.; Bates, M.E.; Morgan, H.; Clark, S.S.; Linkov, I. Resilience and sustainability: Similarities and differences in environmental management applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, R. Sustainability Assessment: Criteria and Processes; Earthscan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 1–254. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, L.; Krogman, N. Social thresholds and their translation into social-ecological management practices. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresque-Baxter, J. Participatory photography as a means to explore young people’s experiences of water resource change. Indig. Policy J. 2013, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Krasny, M.E.; Lundholm, C.; Plummer, R. Environmental education, resilience, and learning: Reflection and moving forward. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitomi, M.K.; Loring, P.A. Hidden participants and unheard voices? A systematic review of gender, age, and other influences on local and traditional knowledge research in the North. Facets 2018, 3, 830–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquez, F.; Vaughn, L.M.; Wagner, E. Youth as partners, participants, or passive recipients: A review of children and adolescents in community-based participatory research (CBPR). Am. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 51, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, R.K. Rethinking environmental science education from Indigenous knowledge perspectives: An experience with a Dene First Nation community. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 24, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet, L.; Goulet, K. Teaching Each Other: Nehinew Concepts & Indigenous Pedagogies; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2014; pp. 1–248. ISBN 0774827572, 9780774827577. [Google Scholar]

- Bird-Naytowhow, K.; Halata, A.R.; Pearl, T.; Judge, A.; Sjoblom, E. Ceremonies of relationship: Engaging urban Indigenous youth in community-based research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, L. Intergenerational dialogue exchange and action: introducing a community-based participatory approach to connect youth, adults and Elders in an Alaskan Native community. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2011, 10, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, L.; Morrisette, V.; Régallet, G. Our Responsibility to the Seventh Generation: Indigenous Peoples and Sustainability Development; International Institute for Sustainability Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1992; pp. 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Restoule, J.P.; Gruner, S.; Metatwabin, E. Learning from place: A return to traditional Mushkegowuk ways of knowing. Can. J. Educ. 2013, 36, 68–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts and theory. Eur. Psychol. 2013, 18, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.G.; DuBois, B.; Krasny, M.E. Framing for resilience through social learning: Impacts of environmental stewardship on youth in post-disturbance communities. Sustain. Sci. 2016, 11, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Learning for resilience, or the resilient learner? Towards a necessary reconciliation in a paradigm of sustainable education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, M.A.; Okamoto, S.K.; Hibbeler, T.; Hibbeler, P.; McIntyre, P.; McAllen-Walker, R.; Hankerson, A.A. The hoop of learning: A holistic, multisystemic model for facilitating educational resilience among Indigenous students. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2002, 29, 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- McKay-Carriere, L. Decolonizing “Cree-atively” through Elder stories. In Teaching Each Other: Nehinew Concepts & Indigenous Pedagogies; Goulet, L., Goulet, K., Eds.; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2014; pp. 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Canedo-García, A.; García-Sánchez, J.N.; Pacheco-Sanz, D.I. A systematic review of the effectiveness of intergenerational programs. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korpershoek, H.; Harms, T.; De Boer, H.; Van Kuijk, M.; Doolaard, S. A meta-analysis of the effects of classroom management strategies and classroom management programs on students’ academic, behavioral, emotional, and motivational outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 643–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvall, J.; Zint, M. A review of research on the effectiveness of environmental education in promoting intergenerational learning. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 38, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinner, J. How behavioral science can help conservation. Science 2018, 362, 889–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Dyball, R.; Fazey, I.; Gross, C.; Dovers, S.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Brulle, R.J.; Christensen, C.; Borden, R.J. Human behavior and sustainability. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marteau, T.M. Towards environmentally sustainable human behaviour: Targeting non-conscious and conscious processes for effective and acceptable policies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 375, 20160371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathwell, K.; Armitage, D. Art and artistic processes bridge knowledge systems about social-ecological change: An empirical examination with Inuit artists from Nunavut, Canada. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steelman, T.A.; Andrews, E.; Baines, S.; Bharadwaj, L.; Bjornson, E.R.; Bradford, L.; Cardinal, K.; Carriere, G.; Fresque-Baxter, J.; Jardine, T.D.; et al. Identifying transformational space for transdisciplinarity: Using art to access the hidden third. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 14, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, L.E.A.; Bharadwaj, L.A. Whiteboard animation for knowledge mobilization: A test case from the Slave River and Delta, Canada. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2015, 74, 28780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Earnstman, N.; Huke, A.R.; Reding, N. The drama of resilience: Learning, doing, and sharing for sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickert, G.E.H.; Bradford, L.E.A. Of research pings and ping-pong balls: The use of forum theatre for engagement water security research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2015, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendis-Millard, S.; Reed, M.G. Understanding community capacity using adaptive and reflexive research practices: lessons from two Canadian biosphere reserves. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2007, 20, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.; Ward, C.R.; Smith, T.B.; Wilson, J.O.; McCrea, J.M.; Calhoun, G.; Kingson, E. Intergenerational Programs: Past, Present, and Future; Taylor & Francis: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 1–249. ISBN 1-56032-420-1. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, S. remembering the past and preparing for an intergenerational future. J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2014, 12, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, T.; Rasmus, S.; Allen, J. Being useful: Achieving Indigenous youth involvement in a community-based participatory research project in Alaska. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2012, 71, 18413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, N.G.; Norman, M.E.; Dupré, K. Rural youth and emotional geographies: How photovoice and words-alone methods tell different stories of place. J. Youth Stud. 2013, 17, 1114–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascher, W. Keeping the faith: Policy sciences as the gatekeeper. Policy Sci. 2017, 20, 3–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.G.; Henderson, A.E.; Mendis-Millard, S. Shaping local context and outcomes: The role of governing agencies in collaborative natural resource management. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2013, 18, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, C. Works and Lives: The Anthropologist as Author; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fortuin, K.P.J.; van Koppen, C.S.A. Teaching and learning reflexive skills in inter- and transdisciplinary research: A framework and its application in environmental science education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 697–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuhiwai Smith, L. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples; Zed Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Matin, N.; Forrester, J.; Ensor, J. What is equitable resilience? World Dev. 2018, 109, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teufel-Shone, N.I.; Schwartz, A.L.; Hardy, L.J.; De Heer, H.D.; Williamson, H.J.; Dunn, D.J.; Polingyumptewa, K.; Chief, C. Supporting new community-based participatory research partnerships. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parlee, B.L.; Geertsema, K.; Willier, A. Social-ecological thresholds in a changing boreal landscape: Insights from Cree knowledge of the Lesser Slave Lake Region of Alberta, Canada. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, M.; Lynes, J.; Hickman, G. A model for developing and assessing youth-based environmental engagement programmes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 552–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Understanding transformation theory. Adult Educ. Q. 1994, 44, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busseri, M.A.; Rose-Krasnor, L. Breadth and intensity: Salient, separable, and developmentally significant dimensions of structured youth activity involvement. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 27, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Krasnor, L. Future directions in youth involvement research. Soc. Dev. 2009, 18, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsall, T.; Forneris, T. Evaluation of a leadership program for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Youth: Stories of positive youth development and community engagement. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2016, 22, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, B.; Vlug-Mahabali, M.; Hermanns, S.; Spijker, E.; van Weert, J. To be involved or not to be involved? Using entertainment-education in an HIV-prevention program for youngsters. Health Commun. 2014, 29, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viau, A.; Denault, A.; Poulin, F. Organized activities during high school and adjustment one year post high school: Identifying social mediators. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 4, 1638–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezirow, J.; Associates. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress; Josey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 1–400. ISBN 0-7879-4845-4. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.G.; Abernethy, P. Social learning driven by collaboration in the Canadian network of UNESCO Biosphere Reserves. In Co-benefits of Sustainable Forestry; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 169–187. [Google Scholar]

- Massie, M.; Reed, M.G. Cumberland House in the Saskatchewan River Delta: Flood memory and the municipal response, 2005 and 2011. In Climate Change and Flood Risk Management: Adaptation and Extreme Events at the Local Level; Keskitalo, E.C.H., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 150–189. ISBN 978 1 78100 666 5. [Google Scholar]

- Wadram, J. As Long as the Rivers Run: Hydroelectric Development and Native Communities; University of Manitoba Press: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1988; pp. 1–272. ISBN 9780887556319. [Google Scholar]

- Gober, P.; Wheater, H.S. Socio-hydrology and the science–policy interface: A case study of the Saskatchewan River basin. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 18, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu, R.; Reed, M.G. Adaptation through bricolage: Indigenous responses to long-term social-ecological change in the Saskatchewan River Delta, Canada. Can. Geogr. Le Géographe Can. 2018, 62, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, E.J.; Reed, M.G.; Jardine, T.D.; Steelman, T.A. Damming knowledge flows: POWER as a constraint on knowledge pluralism in river flow decision-making in the Saskatchewan River Delta. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2018, 31, 892–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendtro, L.K.; Brokenleg, M.; van Brockern, S. Reclaiming Youth at Risk, Revised ed.; Solution Tree Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1990; pp. 1–184. ISBN 978-1-879639-86-7. [Google Scholar]

- Van Brockern, S.; McDonald, T. Creating circle of courage schools. Reclaiming Child. Youth 2012, 20, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).