1. Introduction

“The most dangerous worldviews are the worldviews of those who have never viewed the world” (Alexander von Humboldt).

This paper explores numerous socio-political novelties that are leading to a paradigm shift from stakeholdership to stakeownership in global environmental governance. “Today, more than 80 percent of the world’s population lives in countries that are running ecological deficits, using more resources than what their ecosystems can renew” [

1]. While this is true, it is also misleading, because the rich among us over-consume while the low-income ones under-consume, although the latter group bears the brunt of all ecological damages [

2,

3]. In fact, indigenous people around the world are the least contributors to climate change, yet they are actually under consumers. Furthermore, their livelihoods are threatened given corporate control of their lands. For example, one multinational alone controls over 800,000 hectares of land across Africa, and they are not the biggest foreign landowners (

www.landmatrixitaly.it). 70% of the global land grabbing occurs in Africa, followed by South America and Asia. Across Africa, according to Land Matrix 2018 report, only 9% of the land (40.98 million hectares) is exclusively meant for food production while 38% is for non-food crops and 15% is reserved for biofuels, animal feed, and others. Land grabbing refers to “land deals that happen without the free, prior, and informed consent of communities that often result in farmers being forced from their homes and families left hungry. The term “land grabs” was defined in the Tirana Declaration (2011)” [

4]. Since the past decade, foreign investors have acquired 26.7 million hectares of land, and Africa alone accounts for 42% of these deals. While there are gains in such foreign investments, they hardly trickle down to indigenous peoples and small-scale farmers because of the adverse effects created by such deals. More prominently, most of land grabs are concentrated along important rivers, namely Niger and Senegal rivers and rivers across East Africa, creating poverty and desperation for small-scale farmers [

5].

Indigenous people represent 4000 distinct cultures and 5000 languages that are also threatened even though they are protectors (not protesters) of 80% of the Earth’s most biodiverse areas [

6]. Indigenous people around the world constitute a threatened 5% of the global population, but they also represent 15% of the poorest and are threatened by some multinational corporations and environmental conservation organizations in connivance with their governments. How? At the local or national level, this threat consists of displacement and dispossession caused by extractive industries [

7,

8,

9] and large-scale agriculture by some MNCs in response to the surge in global demand for biodiesel and vegetable oil. This has led to human rights abuses and food and water shortages [

3]. At the same time, environmental conservationists control large swaths of land for conservation purposes, although local communities are adversely affected by such operations that alienate them [

10,

11]. Fairhead, Leach and Scoones [

10] refer to this as ‘forms of valuation, commodification of nature, and the birth of new actors and alliances’ or otherwise known as the ‘green grabbing’ phenomenon.

Apart from big oil multinationals operating in some of the most environmentally polluted regions on the planet such as Niger Delta in Nigeria, large-scale oil-palm plantations are displacing local populations and destroying ecosystems, especially where the institutions are weak in Africa [

12], Asia, and South America [

3,

13] and the rest of the world in general [

6]. The net effect is increased climate change and environmental degradation that, in turn, affect global health [

1,

2,

14]. The dangers are lurking everywhere, and that is an indicator that we are at the cusp of a new epoch of self-destruction for the benefit of a few financial speculators and land grabbers [

11]. The current situation can only be described as a wicked problem because of its complexity and far-reaching ramifications on people and the planet [

15]. On the global front, recent revelations by scientists demonstrate that despite this common knowledge, climate change and global warming, emerging diseases, and chronic diseases are increasing (

https://www.ipcc.ch/) [

16]. Health inequalities and ecological imbalance resulting from environmental pollution, including sea filled with tonnes of plastic, remain a serious challenge in spite of the new innovations to combat them [

17].

In light of the above, this paper has a three-fold purpose: To challenge the current conceptualization of firm-stakeholder engagement, to popularize ‘allemansrätten’, the social innovation tradition for environmental value creation and environmental governance leading to ecological balance, and to introduce the concept of usufructual rights that promotes human dignity and the tutelage of natural resources. Stakeholders are generally conceptualized as those individuals or organizations who affect and are affected by the firm [

18]. The concept is premised on value creation for all these constituents [

18,

19,

20]. We postulate that ‘universal stakeownership’, unlike ‘stakeholdership’, seeks to capture how societies and communities at the grassroots fundamentally take ownership in transforming the current generation’s socio-economic and institutional structures in ways that truly democratize our democracies, thereby bringing about greater equity, justice, peace, protection of our ecology and the sustainability and responsible use and governance of our natural resources [

8,

16,

21]. More prominently, it is argued that current debates about stakeholders mainly offer normative prescriptions to firms to engage with stakeholders although true action for change will always be deferred unless the current top-down paradigm is decolonized [

22].

In what follows, this paper elucidates the problem of the local–global effects of environmental and natural resource concerns using the ‘glocal’ as our unit of analysis given the mutual effects and dependence. The paper further delineates the changing paradigm from stakeholder theory to stakeowner practice with the support of a Scandinavian model (as a case) whilst introducing ‘allemansrätten’, the social tradition and usufructural rights, as both an emancipatory regime for change and redemptive strategy for global and local environmental stakeownership. To avoid repetition, we explain these ‘novel’ concepts in turn.

2. Problematizing the Current Local-Global Environmental Resource Imbalance

The 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs; see

http://sdgcompass.org) have three specific points (out of 17 goals) directly aimed at sustaining our ecology:

Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development.

Goal 15: Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss.

Goal 16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels.

These points are useful and desirable with a nice ring to them and yet they are the same old top-down approaches where governmental agencies, experts, international hybrid organizations and the media are to lead in driving the change and agenda-setting [

23]. Whilst they articulate what is to be done, they are silent on whose resources would be used to correct, recuperate or undo previous or ongoing environmental damages that indigenous people have to struggle with.

A July 2019 report by the UN on the progress of the SDGs saw the UN Secretary-General António Guterres joining in raising the alarm about the retrogression of SDGs in almost all areas. “It is abundantly clear that a much deeper, faster and more ambitious response is needed to unleash the social and economic transformation needed to achieve our 2030 goals,” he wrote [

24]. A separate study by independent experts (a joint project of the Bertelsmann Stiftung in Germany and Sustainable Development Solutions Network in New York) corroborates the concern about the crisis that “progress has been uneven at best, and in some cases has been reversed” [

24]. Further, “the study found that all nations were performing worst on addressing climate change, and no country has achieved a ‘green’ rating. Many obstacles to success or the causes of reversals included tax havens, banking secrecy, poor labor standards, slavery and conflict” [

24]. This is why local stakeowner governance matters.

The top-down (power asymmetry) firm-government-NGO relationship with local communities is hardly accounted for in practice. More prominently, the complicatedly worded agendas are not correctly communicated in a user-friendly narrative to galvanize public support. Thus, the English language mass media in particular reports select themes of interest (e.g., gender equality) without embedding them in the overarching concept of SDGs in people-speak. This “misses the opportunity of framing them in the broader, overarching concept of sustainable development. This may be a significant sustainability faux (error)—Great political intentions need efficient implementation tools, not just political resolutions” [

23]. Further, the ratification of international conventions by nations does not necessarily translate into actual enforcement. This explains why the degree of success will depend on the independence of endogenous deliberative institutions, enabling democratic governance and non-invasiveness of exogenous forces [

25]. We subscribe to Vatn’s [

25] definition of institutions as “the conventions, norms and formally sanctioned rules of a society. They provide expectations, stability and meaning essential to human existence and coordination. Institutions regularize life, support [cultural] values and produce and protect [shared] interests.”

Furthermore, as much as SDGs are important and necessary, they also ignore planetary vandalism [

26,

27] and the powers which constrain resource use around the world [

28]. Orr [

27], borrowing from Wendell Berry’s words compares these vandals to citizens. These vandals are highly educated professionals who seek to maximize their utility (fulfilling their fiduciary duty) at the expense of people and the environment [

26]. The word ‘professional’ makes it self-explanatory that these individuals are highly trained and qualified. They are neither ignorant nor uneducated but are highly aware of the adverse effects of their techno-scientific, military, political, pseudo-ethical and managerial maneuvers but nonetheless put profits before people and planet. They muster strategy and ignore ethics and they may also be trained in some of the best universities in the world [

26,

27]. The pedagogical and ethical implications are that such individuals in key positions switching to sustainable posture (i.e., people and planet before profits) have the potential to bring about seminal changes in our quest for global environmental sustainability. That, however, is a challenge. That is why policies and educational programs targeted at these people matter because they either condemn or condone with the current situation. This cannot naturally be twisted to include all those professionals (or MNCs) who are not involved in natural resource appropriation in weaker institutional contexts. Likewise, if a news headline suggests that ‘scientists have developed a dangerous molecule’, it does not mean that all scientists in the world were involved in that operation.

In part, we all modern consumers are vandals to a certain degree because we contribute to environmental degradation and climate change due to our consumption patterns. However, the extent to which professional vandals in charge of big extractive corporations in alliance with weak governments oversee environmental destruction [

3] is on a different level [

1,

7].

It must be emphasized that SDGs are the United Nations’ agenda for the world with financial instruments coming from industrialized nations, donor organizations, and other financing instruments. Success depends on their level of commitment and how much financial and technical resources they are willing to put in as in all development agendas. This is because external financing or borrowing is a big part of the budget in developing nations even though they are resource-rich. As has been argued by Baker [

29], much of this can also be symbolic commitments in the form of declaratory politics. Of course, a possible solution is fairness in international trade and a vigorous fight against corruption, mismanagement and boutique projects. Thus, a new government from the EU or US that decides to reduce financing of projects or ignores environmental issues will immensely affect any advancement in low and middle-income nations even though industrialized nations are the major contributors to climate change. However, a similar scenario is not likely in Scandinavia [

30], for example, since actual power manifestly belongs to the people and not corporations [

21]. Besides, others cannot be held responsible for the failure to accomplish anything because the SDGs are merely principles for collective actions in 17 major areas and not legally binding laws [

31,

32]. In the end, we argue that communities are responsible for their own destiny, land, natural resources and identity construction through resource governance [

16,

33] and the SDGs are simply useful guidelines and commitments. Resource availability, political will and the enabling nature of national institutional structures [

6,

34,

35] along with public-private and civil society partnerships [

36] where local communities take a stand as equal partners of development under strong democratic institutions is the tried and tested formula that determines success.

Hitherto, moral persuasions to deter planetary vandalism and other forms of destruction of ecosystems have mostly failed because the psychological framing of stakeholders has mostly precluded citizens/society (but included a managerial and political class) as the real owners of all we have and the governance and institutions around its use [

21,

37]. ‘Governance’ then refers to both “formal and informal devices or mechanisms through which political and economic actors organize and manage their interdependencies” through dialogue or negotiations, setting of standards, performing allocated functions, monitoring compliance, reducing conflict and resolving disputes in their quest to protect their interests [

38]. More precisely, “environmental governance encompasses our relations to nature, spanning institutions and policies in fields such as biodiversity loss, climate change, land use and pollution” [

16].

3. Analyzing the Current State of the Stakeholder Concept

Clearly, stakeholder theory has gained currency and this much can in part be attributed to the fact that the socio-economic and environmental stakes are critically higher than we formally articulate. These include the environmental and health issues which directly impinge on people’s happiness and wellbeing [

14,

16]. Stakeholder notions in their current form are not helping the cause of the marginalized, distal and weak stakeholders [

39,

40] given their weakened social status, economic powerlessness and lack of agency and voice [

8,

22]. This makes it difficult for perpetrators of environmental degradation to be held responsible [

9,

41,

42]. By perpetrators we do not only mean the firms that produce externalities or public bad but also firms that do not honor their legal and social obligations which they could have done with the power and resources gained from society and its environment [

43,

44,

45]. As Banerjee [

46] asks in his seminal work ‘National interest, indigenous stakeholders, and colonial discourses’, whose land is it anyway?

However, the stakeholder concept is not without limitations because of its vagueness, overly simplistic presentation, and in some cases meaninglessness, albeit an important starting point for firm-constituent discourses [

20,

39,

40,

47,

48]. Those limitations may not be the result of an inherent flaw in the conceptualization, but because they reflect the changing times and their accompanying grand medico-techno-scientific and environmental challenges in the era of globalization where the state is retreating from its traditional responsibilities [

49,

50] and gradually losing control of sovereignty [

51]. In broader terms, stakeholders refer to those interest parties, individuals and groups who affect and are affected by the practices of the organization. This means that stakeholders can make claims of ownership, have rights, or socio-economic, environmental or moral interests to protect in their relationship with the organization [

18,

47,

52]. An important characteristic of stakeholders is that they are beneficiaries and risk-bearers of the organizations’ actions [

18,

53,

54].

In theory then, this current understanding should make a stakeholder a stakeowner in the short, medium, and long-term. In practice, however, only some stakeholders are actively involved in actual wealth control and appropriation while others suffer externalities especially in our case, resource-rich settings [

9,

13,

46]. More prominently, these marginalized communities have to wait to be engaged with under conditions of diminished status and bargaining power [

39,

40]. Further, those stakeholders, who take action, only do so to protect their minor interests, and immediate situations within the limits of their power to influence firms, particularly in the presence of strong stakeholder constellations and institutional pressures [

55]. Power dynamics and status that comes with socio-economic influence and resource control define the relationships as to who engages whom in producing optimal outcomes [

39]. The keyword here is power, which is a “capacity premised on resource control” [

56]. These asymmetrical power relations between the organization and stakeholders have affected the general understanding of stakeholdership, leading many to not register any major dissent–except prescriptions and admonishment about what the firm ought to do.

This study is a step towards extending the stakeholder theory to reflect the current ecological turbulence and the destruction of natural resources–land, air, water, atmosphere, flora, and fauna [

12]. It also serves as a response to the ecological, health and livelihood concerns of the global population, especially those of indigenous peoples and disadvantaged communities. There are some critical elements which, once left out, make an analysis of stakeholders bereft of any truth or deeper meaning. This explains the complexity of the current mechanisms for environmental and natural resource governance at the local and global levels. More so, the issue of resource governance, as pursued by several intrepid scholars, instructively shows multiple dimensions: philosophical, ethical, historical, scientific, humanistic, futures, foresight, socio-economic, political, managerial, jurisprudential, engineering and decisions science among others. All this requires cross-referencing and a multidisciplinary approach to bridge the gulf in their compartments because none of them has a monopoly of the discourse over sustainability. Unfamiliarity with these dimensions and the numerous studies and tails of the travails of indigenous people does not mean such discourses are incorrect, a generalization, a dramatization or just ‘emotive theatrics’. Under the United Nations human rights charter, access to resources is a human right, not a privilege in people’s pursuit of wellbeing and happiness.

Even under conditions of deliberative and democratic rulemaking and will formation [

57,

58], it would be a serious act of self-destruction to hand over the ethical and sustainable control of our natural resources into the hands of private enterprises without an equal or greater power in the hands of society. This is because indigenous people without power, status, and income would be short-changed as usual [

2,

3]. More so, our very survival depends on our environment (not the feudalized type)–this is why we are stakeowners of all we are and have without the possibility of remaining oblivious or indifferent to environmental vandalism. Concurrently, we recognize the sophisticated nuances inherent in the interpretation of stakes–stakeowners are embellished in the stakes, making them both owners and part and parcel of the stake (their personhood/humanity and their dependence on the environment).

5. Historical Foundations of the Stakeowner Reasoning

The above position on stakeownership is not a novelty but there is now a systemic (widespread) political action that is impinging on the nature of environmental governance globally and locally. This is because new information technologies in their unprecedented use are giving voice to the voiceless and connecting formerly dispersed and fragmented groups, disciplines, and intellectual and political resources. ‘Degrowth’, ‘deglobalization’, ‘globalisolationism’ [

69], ‘political ecology’, ‘radical geography’, ‘circular economy’, ‘environmentalism’ ‘green politics’ ‘divestment movements’ [

70] and the increase in socially responsible investment funds. Theseconstitute the conglomerate of concepts and movements that are putting society/environment at the centre of attention. Mutations in the local-global norms of society and the importance of environmental conservation and its impact on health have energized multiple fronts for environmental sustainability. This has led to new global pacts on one hand and citizen activism on the other about issues such as climate change, emerging diseases [

71] and inequality [

14,

17]. Society is therefore entitled to rights, privileges, and responsibility of owning and conserving itself for posterity. This is not only revolutionary but an evolutionary position to ensure our actual adaptation and survival in spite of the emerging grand challenges.

The foundations of these arguments have been laid in classic works of the 20th century such as [

34,

35,

72]. More recently, similar arguments have been made by Blyth [

73] and Bromley and Anderson [

74] on institutional change and economic transformations, Sen [

37] on welfare economics, social choice theory and issues of social justice and Stiglitz, et al. [

75] on why GDP doesn’t add up but a more holistic view of the human condition is needed.

The introduction of stakeownership as a paradigm shift that gives power to society does not seek to supplant stakeholder theory. However, to use the words of Jesus the Christ, we “have not come to abolish them (the Scriptures) but to fulfill them”, so we rather seek to fulfill stakeholders’ ultimate end-goal of value co-creation/conservation and global ownership and tutelage of the environment and natural resources. Thus, stakeholder theory is a foreshadow of the society’s new pact with the firm, nation-states, and other constituents–the universal stakeowner paradigm. Here, the firm is simply a product of social systems and not an antagonist of society’s wellbeing. Stakeholder theory has offered useful beginnings, but as matters stand, it decouples the environment from society while mediating between the firm and certain economic actors. Concurrently, it gives little voice to humanity (while focusing on specific identifiable actors) as if all depended on the firm under the guise of dialogue [

76].

Universal stakeownership on the other hand, speaks to how society must as a matter of urgency rise up from the by-stander position and engage the minor constituent, the firm, in a new institutional order where radical socio-economic, normative and legal constraints and incentive structures define and shape corporate actions–in other words, the deinstitutionalization of the old order [

67]. This is not to suggest that all societies are inactive in this movement–there are only degrees of awareness and possession of the power to act. Here, we practice politically conscious or woke ownership of the environment and natural resources, to hold and defend the stake in the spirit of justice and fairness and the obligation to survive and let current and future species survive, too.

While progress has been made on many fronts to put society and environment at the center, it is self-evident that sustainability becomes a self-defeating concept when society seeks clean air, uncontaminated water, unpolluted environment, food that is untainted with deadly toxins and welfare but does not radically constrain or set boundaries on corporate actions that harm the environment. Only by fundamentally altering the current ‘rules of the game’ within different institutional frameworks will society have a real potential to strengthen its democratic foundations [

57,

58] and possible environmental and welfare outcomes [

77]. This is no utopian dream. There are already pockets of examples around the world as will be demonstrated in the next pages.

6. Theoretical Delineation of the Stakeholder Theory and Universal Stakeowner Paradigm

As soon as the land of any country has all become private property, the landlords, like all other men, love to reap where they never sowed, and demand rent even for its natural produce. [

78].

This study bases its arguments on ‘progressive conservativism’ (which sounds oxymoronic) where matters of equity and efficiency are not deemed incommensurable in ways that privilege more innovative means of enhancing productivity and optimal use of our environment and natural resources. A radical conceptual extension to stakeholder theory matters. Without this, society may succumb to a dangerous undercurrent and an elective affinity with the status quo who benefit from unsustainability whilst using CSR as a smokescreen [

48,

79]. Additionally, uncritically valorising the position of the status quo with its flourish of contradictory and inaccurate characterization of sustainability [

29,

80,

81] retroactively aborts society’s future ideals from the uterus of a preferred future (to use the words of Dr M. Dyson) at the expense of humanity as a whole for the benefit of a few speculators and investors. Rather, we privilege concepts such as power asymmetry, institutions and democracy [

57,

58] that define outcomes of firm-stakeowner relations and shed light on the full breadth and profundity of current understandings of stakeholder status. We further interrogate received wisdom by transitioning into stakeownership in relationship to environmental resource governance.

This study practices a combination of (i) stakeholder perspectives [

18,

20] and (ii) social institutional systems that are concerned with identifying the various institutional mechanisms by which economic activity is coordinated [

16,

21,

82]. Additionally,, we consider the circumstances under which these mechanisms are chosen, by seeking to comprehend the logic inherent in different coordination mechanisms [

64]. Economic coordination then is the process by which a matrix of interdependent actors relates to each other to ensure economic exchanges and to solve or regulate the problems inherent in such exchanges. In the former perspective, we also build on varieties of extensions of stakeholder theory, on faceless and nameless stakeholders by McVea and Freeman [

20] and distal and proximal stakeholders by Ahen [

39] or the marginalized by Derry [

40]. According to McVea and Freeman [

20] the received understanding of stakeholder theory focuses vaguely on stakeholders per se while ignoring the fact that they have real names and faces as specific as all individuals. Identifying and engaging them in a nutshell, gives a deeper meaning to stakeholder engagement. Further, we build on Ahen [

39] who argues that the marginalized and voiceless are ignored due to power asymmetry and socio-economic status where proximal (those who are close to economic and social status) are heard and engaged with, while the marginalized and distal (not only in the literal sense) are only spoken to or not taken into much consideration at all. This is simply because such constituents lack any affinity and proximity claims to the centers of power–the firm, organization, and government. Additionally, Ahen [

83] also offers taxonomy of opportunities that are squandered when firms fail to productively engage with stakeholders. They include: Lost opportunity to offer value propositions, missed opportunity to co-create value, misappropriated opportunity to market share, stalled opportunity to attract investors and institutional support, closed opportunity to knowledge sharing via collaboration, alliances and new markets that facilitate new learning and disruptive innovations with and through stakeholders. Here too the focus is on what firms need to do for society.

Further, the limitations of the stakeholder approach have been elucidated by Heikkurinen and Bonnedahl [

84] as following a binary trajectory of market orientation and stakeholder orientation, with the latter being a Freemanian school of thought. They argue that whilst both appear to have some minor differences, both shift responsibility to others who affect the firm, emphasizing the pre-eminence of economic utility as an underlying requirement. Further, while both market and stakeholder approaches are initiated by the firm, they require of the market to respond. Here again, the economic bottom line of the firm is spelled out boldly above the intrinsic good in value creation for the firm and the society in which the firm is embedded [

48]. This has led many to pose the question as to whether corporate responsibility is profitable or aids firm performance (profitability, reputation market share) [

85] as if it were an option to be responsible towards the environment or device new ways of improving it. Additionally, Heikkurinen and Bonnedahl [

84] argue that both market orientation and stakeholder orientation accept to play based on the rules of the game (to use the words of Douglas North [

65]) of the prevailing economic doctrines. Here, however, value is simply reduced to economic and human capital while natural capital is left out as if it did not matter. As a departure from the above, the authors introduce sustainable development orientation whereby the firm initiates strategies not only because they have economic incentives but because of the intrinsic value of the environment. Whilst this is a good theoretical step forward, an addition can be made since this view sends us back to square one because it leaves so much power in the hands of the firm, neglecting the fact that the firm is a rationalized open system [

86], made and ruled by profit-seeking actors who may choose not to honour sustainability orientation in the absence of enforcement mechanisms [

55]. Without institutional constraints, this remains only a theoretical reflection with little else beyond that. This is seen for example in oil spills, emission cheatings and tainted foods [

87]. The abuse of corporate political power in low-income nations, excessive lobbying (

www.opensecrets.org/lobby) [

88] and trickle down economic thinking which guides the instrumental behavior of firms are not some out of the blue aberrations [

48,

89] but constitute a systemic terror on our biosphere which requires radical action from its actual custodians. Thus, society as the stakeowners. This reasoning is anchored in the objective truth that our survival depends on ourselves as part of the environment. The organization only serves as a tool for enhancing this process, not as a substitute of the true custodians and natural trustees, i.e., society and its formal and informal institutions [

21,

37].

Therefore, in the second perspective, our practice of institutional theory focuses on the dimension of varieties of capitalism [

90] and social institutional systems [

64] as the critical foundations for the sustainable environmental and natural resource governance. It is argued that global economic, ecological, and health crises or human development and quality of life are simply a mirror image of the prevailing institutions: cultural, cognitive and regulative and normative systems which together with activities and resources add meaning to life [

91]. Stakeownership also reflects the nature of our relationship with our environment where systems of production occur. Here, we delineate the nature of varieties of capitalism (liberal, welfare, liberal crony or a mixture of all these, depending on which political party is in power) as defining the difference between value destruction and value creation for a few. Moreover, the old order of stakeholder perspectives invites many questions and shows glaring limitations in our sustainability ideals across different countries. That further explains the differences in comparative advantage in the long run. Although this is less cryptic than one would expect, it is probably the Holy Grail that defines the difference between neoliberal capitalism (pro-market liberalization philosophy with emphasis on private ownership and lesser responsibility) and welfare capitalism [

64] that seeks progressive solutions to mainly universal problems (environmental justice and public good issues) that do not leave others out. This is the centrality of the issue of equity in the midst of global inequality where access to resources is in excess in one part while being scarce at other parts of the world.

In social welfare systems, then the fundamental institutional pillars are structured to ensure that policies on health, education, natural resource preservation, international trade, innovations and social and population health give impetus to continuous advancement and protection of individual entrepreneurial initiatives that do not preclude societal happiness and peace (public goods) [

92]. This shows a useful distinction between welfare-oriented systems and liberal market economies where issues are left to demand and supply–with limited regulation.

In theory, stakeholders are stakeowners too since they affect and are affected by the firm’s operations. So, what is the point in moving us from stakeholders to universal stakeowners? Here is the conceptual challenge. Investors and stockholders are as much stakeholders as the people in a minor community where rivers are being polluted and forests plowed down by a mining company or commercial palm oil producers [

93,

94]. While the stockholders receive massive dividends and CEOs receive millions in compensations and benefits [

95,

96] (

www.aflcio/paywatch), actual owners lose their livelihoods through displacement and dispossession [

3]. The relevant question worth asking is: Can both be equally considered as stakeholders in practice or in theory?

Stakeholder perspective is an old order which has suffered misinterpretation, fatigue, and misapplication in the real world [

40,

48]. This has brought about several intellectual and practical challenges with regards to the contextual vagaries of firm–stakeholder interactions and collaboration, be it firm-customer, public-private partnership or private-civil society partnership. Current stakeholder postulations do not necessarily seek fundamental institutional change. Hence, they miss some central themes of firm-stakeholder vision misalignment, especially in emerging economies and deprived communities of weaker social status [

13,

48] in highly industrialized nations [

40]. This has meant that the taken-for-granted nature of the stakeholder concept leads to stakeholders becoming side-lined observers rather than proactive participants, who as a norm, and in a natural way are supposed to work in harmony with, through, for and beyond the object of their stake.

There is also a historiogeographical argument. In theory, stakeholder theory is limited to business and non-business organizations and how they relate to certain constituents [

47]. Environmental and natural resources also belong to the memory of those who fought for the resource conservation within specific territories, the current generation that consumes and the posterity whose share of the resources remain uncertain because the corporation is not giving up ground in their claim.

Additionally, when we are stakeholders, our responsibility is mostly limited by definition to what we affect and are affected by, here and now both in legal and moral terms. We can be active or inactive. We can choose to care only about the privately owned and contextually defined stakes as employees, stockholders or consumers but not how those issues affect others unless we are constrained by strong institutional structures or individual convictions, such as environmental conservatism or giving to philanthropy. It is for the future that sustainability issues begin to merit serious attention when analyzing universal stakeownership.

8. The Swedish/Finnish Ecological Case as a Proxy for the Scandinavia

‘Everyman’s right’ (in Finnish: ‘jokamiehenoikeus’; in Swedish: ‘allemansrätten’) means that the country’s forests and lakes are for everyone to enjoy, not a corporate or a special individual’s property [

99]. The intrinsic but implicit implication is that since rights are a two-edged sword, it is also everybody’s responsibility to uphold the contract of social mores as an inherited call to duty. It is not questioned or debated. It must be advanced with new investments and innovations for future generations. This is the socio-ethical institution and value-system etched into the national character because it is inculcated into the minds of kindergarteners and forms the basis for ‘how-to’ in the entire population’s interaction with the biotic and abiotic environment. This is not uniquely Finnish or Nordic. Researchers have been studying about common pool resources (CPR) [

100] such as water for irrigation and pastures. For example, Kasymov and Zikos [

28] study human actions and institutional change and the impact of power asymmetries on efficiencies in use of pastures in Kyrgyzstan and Zikos, Sorman and Lau [

33] study water securitization and tribal/national identity in Cyprus while Obeng-Odoom [

68] studies agro-ecology and sustainable food systems in Africa. What is unique about the Finnish/Nordic case is the institution of resource democracy [

101] which guarantees citizens’ access to lands and natural resources whilst protecting property rights [

101]. See

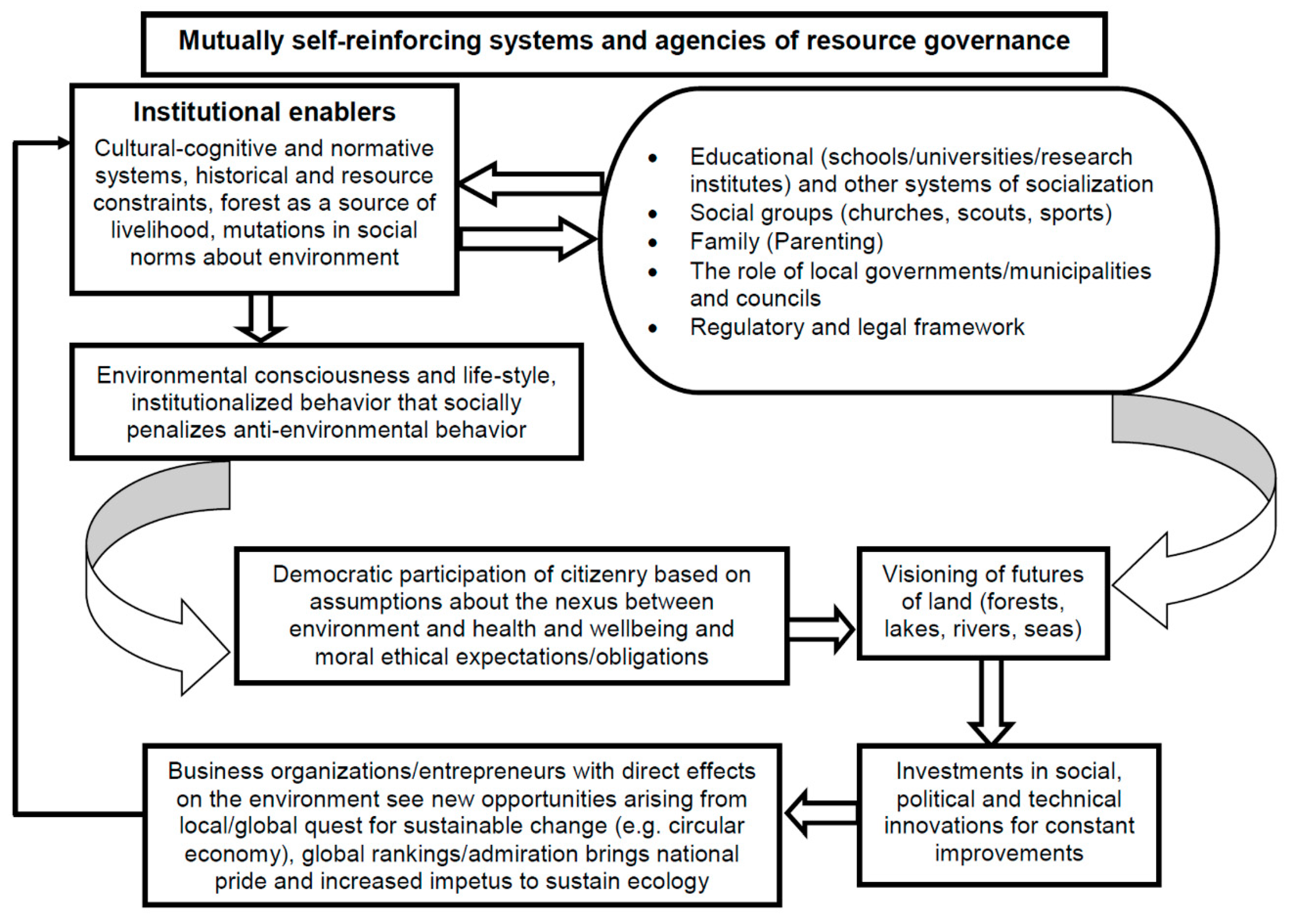

Figure 1 for institutional foundations of everyman’s right:

This, explains why Finland remains sustainably green and its 100,000 healthy lakes [

101] remain as exhibit ‘A’ model for the universal stakeowner paradigm. Finland is not alone in creating such a model. It is a Scandinavian thing [

47]. In welfare-oriented nations, ecological policies mostly have national health interest at the core [

47]. For example, “Since 2000, Yale’s annual index has ranked the top-performing countries for the environment, based on how well they’ve fared at protecting human health and vulnerable ecosystems. It looks at a number of specific metrics to give each country a score out of 100” [

102]. According to the Yale report, Finland has committed to reach ‘a carbon-neutral society’ that is at the level (not exceeding) of ‘nature’s carrying capacity by 2050’. This search for positive health impacts is focused on “climate and energy, biodiversity and habitat, water resources and air quality”. Iceland, for example, acquires all its electricity and heating from renewable sources, with a score of 90.51. Iceland was also third for health impacts, as well as climate and energy and fourth for air quality. Sweden came third, scoring 90.43, ranking fifth in health impacts, 10th in climate and energy, and in the top 20 for both sanitation and water resources. The country earned near-perfect scores for drinking-water quality and waste-water treatment. In order to support environmental protection along with economic growth, Denmark (in fourth place) has pledged 13.5 billion Danish krone (approximately US

$1.9 billion) to its Green Growth initiative. Denmark scored 89.21. [

102].

In Finland, there are credible enforcement mechanisms in place to ensure that firms operate within the constraints of their regulatory mechanisms. Firms understand that they are only given the opportunity to obtain contracts to drill, mine, fish, fell lumber or engage in any form of production or distribution. However, under no circumstance should such rights trump on the ownership rights of those with the least disposable household income, least power, and perceived lack of urgency or an arbitrarily defined legitimacy (in sum, the marginalized). This national attitude is commonplace in Nordic societies. Thus, the power of the societal members, their legitimacy and sense of urgency to defend the common heritage and be respected is not a question for discussion. Therefore, communities as universal stakeowners are never at the mercy of firms merely as stakeholders or ‘children of a minor god’. They do not beg for environmental rights, they lay claim to them as stakeowners. This explains why there are more sustainability-oriented technological and social innovations in the Nordic countries than value destruction [

47,

101]. This new and radical perspective of stakeownership, seeks to limit the unbridled power of the organization that now dictates to society. Consider the position of President Tarja Halonen of Finland in the book

100 social innovations from Finland [

101]:

Finland’s strong competitivity and high standard of living are based on Nordic welfare society, which motivates individual efforts and self-development, but also provides communal support. Democracy, respect for human rights and the principles of a constitutional state, as well as good governance are a solid base for a society. In Finland, the state and the municipalities play essential roles in social welfare and health, as well as education and research, but citizens themselves also keep the system alive through their role as initiators and service providers in different non-governmental organizations.

‘Citizens themselves’ is the keyword here. A society’s strength lies not in how it treats its strong and powerful members, but how it succeeds in lifting up its weaker members. Thus, ‘the earth has enough for everyone’s need but not for everyone’s greed’. This, in fact, is the massively radical shift from stakeholders to universal stakeownership. There is a history behind this reasoning across the Atlantic. The United States, just like many former colonized nations paid taxes but were refused representation at the law-making and decision-making arenas by the colonial administration. Their demand that ‘no representation no taxes’ was the voice of dignity that secured them independence in 1776. We argue that the same approach must work anywhere to ensure equity and sustainability that makes resource democracy meaningful with regards to our shared inheritance of natural resources. Thus, although UNESCO world heritage has a nice ring to it, it is the local community that must be empowered with the higher consciousness of who they are and the importance of their environment that shapes their wellbeing along with the institutions that shape their daily life. In furtherance of this view, it is also argued that there is no power wielded by corporations that was not given by society through procedures that many still find unclear and mystifying, except when there is transparency and grassroots democratic empowerment.

Therefore, instead of asking how the firm can engage stakeholders on its own terms, time, place and convenience, we reverse this old order by asking how societies in their idiosyncratic institutional orders can engage the firm by creating awareness about requirements, incentive structures and penalties with clear enforcement mechanisms. Thus, in the old order, until now, the firm appears indispensable and invulnerable and is therefore given the freedom to engage stakeholders willingly through voluntary governance mechanisms (VGMs). In the new order, firms do not get to choose alone, but a legally binding and normatively inspired deliberative process defines the rules of the game in favor of societal needs. In the new order, the citizens have names and faces, the votes of even the most marginalized automatically count and they are by right visible, recognized and respected as is the case in the Scandinavia. The contrast is the case in indigenous communities where politics/sham democracy works to disenfranchise them.

This is not to suggest that the Nordic models are perfect. Here are a few examples of the current situation—partly progressive and partly controversial. Norway, for example, depends very much on oil from the North Sea. Environmentalists note that the effects on the environment are massive. As Sengupta [

103] puts it, Norway is both a ‘climate leader and an oil giant’ simultaneously. This is a paradox that Norway has been seeking to resolve by renaming Statoil as Equinor as a way of showing its ecological responsibility [

104]: “

The new name Equinor is formed by combining ‘equi’, the starting point for words such as equal, equality, and equilibrium. ‘Nor’ is intended to represent the company’s Norwegian origin”. With the government as majority shareholder driving this change, Equinor seeks to disinvest wealth funds in firms with controversial investments such as oil and gas [

105]. It now seeks to shift from an activist (advocacy) investor to an active investor position in order to push for eco-friendly policies, practices and innovations (e.g., wind, solar and renewable energy sources) as a moral responsibility of a corporate investor [

14,

106]. This is in line with Norway’s historical vision to be a global model of corporate responsibility and sustainable practices [

30]. This posture of recognizing and fixing deficiencies to ensure sustainability is clearly shared by all the Nordic nations as an institutionalized expectation from society and economic actors [

47].

9. Extractivism: Comparing the Ecological Case of Other Resource-Endowed Economies with Scandinavia

Extractivism is the system of taking natural resources from colonies across Africa, South America, and Asian countries [

107]. The term ‘extractivism’ (pillaging or indiscriminate resource seeking behavior) describes an international business practice which mostly refers to the use of heavy-duty, large-scale industrial machinery to remove large quantities of natural resources from mostly virgin soils. These are then exported to home countries of mostly big multinational firms with little or no value-added processing [

12]. Apart from traditional natural resources such as minerals, gold, manganese, bauxite, copper, cobalt, zinc, tin, diamond, uranium and fossil fuels, extractivism also pervades in commercial farming, forest, and fishing industries [

7,

8,

12,

108]. This practice leads to the dispossession of indigenous communities, displacement, and poverty [

109], desperation [

3,

13,

97]. It has also contributed to regional instability, and both serve as a distraction from the major externalities such as pollution (created by the profiteering itinerant professional ‘vandals’ [

7,

13,

26,

89,

110].

What all the above problems have in common are their inherent complexity and their ‘global’ scope and impact. A case in point is the resource-rich Congo that is eternally in conflict whilst the extraction of natural resources continues unabated. Examples such as Nigeria’s Delta region, the Congo, and even the Flint water crisis in the US speak volumes about what is ignored in extant literature. In liberal capitalist countries, there can be lenient, stringent or intentionally deceptive political maneuvers that hardly favor constituents. Stakeholders, treated as factors of production are also managed through PR strategies that favour the powerful. Here is an important point worth considering.

Stakeholder theory assumes false universality, but as with a variety of capitalisms, there are different stakeholders in theory and stakeowners in practice. Nordic countries are markedly different from liberal capitalist systems and developing economies which are dominated by corporate-owned resources. Developing countries cannot afford the same speedy and massive improvements to their deteriorated natural resources as in the Scandinavia, not because they lack the financial resources but because they do not control the value chains of their own resources for financing the projects of ecological renewal [

111]. Clearly, governments and dysfunctional institutions play a significant role in producing these less desirable outcomes [

7,

9]. The natural environment of developing countries is negatively shaped by the extraction of natural resources, modes of production, consumption, and disposal in concert with corrupt government officials [

12]. However, a deeper analysis will show that these forms of destruction are just the symptoms of a much more profound institutional problem. The natural resources are not in practice, everyman’s right [

99], but the rights of the powerful unless the ownership is democratized.

What then, must the response be after moving from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to SDGs? While this requires enormous technical inputs, mere recognition of the problem or increase in technology cannot serve as a solution to massive ecological problems. Thus, besides managerial values, the timing, operational mechanisms and resource allocation for fixing this, there is also the need to factor in the questions of efficiency and ethical responsibilities to ensure the fruitfulness of any realistic approach in the long run. The paradox is that the countries which score the highest are deemed cutting-edge, innovative, and advanced economies whilst indigenous and native communities which live in harmony with nature are deemed primitive or manifestly incapable of intelligence. However, indigenous communities have, for millennia been critical in sustaining the ecology through time-tested traditional technologies which the current generation now struggles to replicate. In what follows, the fundamental axioms of stakeowner paradigm with understandings from the two case studies are analyzed. See

Figure 2 for the historical and intergenerational succession of global stakeownership.