Abstract

Based on the summarization of previous studies, this paper constructed an analytical model on the driving factors on the choice of farmers’ livelihood strategies in nature reserves, covering the aspects of natural disasters, public policies, family characteristics, and livelihood assets, and this paper took Zhagana Village in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau as an example to conduct an empirical study. The empirical results show that non-agricultural production strategies, especially a tourism-oriented strategy, are currently the primary livelihood preference for households in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. During the process of livelihood strategy selection, households are influenced by exogenous factors like public policies and natural disasters, as well as by endogenous factors like family characteristics and livelihood assets. Among these factors, the soil erosion as well as the tourism development policy would be the restrictive factors when choosing an agricultural production strategy, or the incentive factors if a non-agricultural production strategy were to be chosen. Meanwhile, anti-poverty development policy, location characteristic, and economic characteristic are the incentive factors for households who want to choose an agricultural production strategy, or the restrictive factors if they would like to select a non-agricultural production strategy.

1. Introduction

The correlation between humans and the ecosystem is one of the core scientific topics of sustainable development and livelihood, as the most basic behavioral patterns of humans play an important role in driving the evolution of the man-land relationship [1,2]. Using the most comprehensive global map of human pressure, scholars show that 6 million square kilometers (32.8%) of protected land is under intense human pressure. For protected areas designated before the Convention on Biological Diversity was ratified in 1992, 55% have since experienced human pressure increases [3]. In China, the vast majority of nature reserves are located in areas where humans have inhabited. About 30 to 60 million people live in different types of nature reserves or in surrounding areas in order to carry out activities related to agricultural production [4]. The livelihood strategies of these farmers, as the most basic decision-making unit in the nature protection area, determine the utilization and efficiency of natural resources, and have an important impact on the sustainable development of nature reserves.

In the mid-1980s, international organizations and research institutions represented by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) and Britain’s Department for International Development (DFID) began to turn their attention to the issue of the livelihood of households. As deeper exploration on the related topics have been conducted, scholars started to work on setting up a series of livelihood analytical frameworks, such as the Livelihood Security Framework [5], the Livelihood Diversification Analytical Framework [6], and the Sustainable Livelihood Approach [7]. Among all kinds of livelihood analytical frameworks, the livelihood strategies of households have become the key focus of attention. A livelihood strategy is an activity or a choice made by people to reach their livelihood targets and their combination, where this specific choice and their combination are based on asset acquisition, opportunity recognition, and the actor’s own wishes [8,9].

Currently, a growing number of studies hold that a livelihood strategy adopted by a household is so dynamic that the household tends to change their livelihood strategy to adapt to a new man-land relationship when the environmental background, livelihood assets, as well as policies and systems are undergoing drastic changes [10]. On the whole, the driving factors for the selection of livelihood strategy by households can be divided into two types—the endogenous factors and exogenous factors. For households, livelihood assets are the representative example of endogenous factors. Generally, related studies believe that livelihood assets of households are inevitably and closely related to their livelihood strategy, and this relationship is embodied in two aspects: first, livelihood assets are the basis for households to achieve the transformation of livelihood strategy [7], while the quantity and diversity of livelihood assets of households promote the diversification of the livelihood strategies chosen by households. Also, the lack of livelihood assets limits their livelihood strategy choices [11]. Second, different combinations of livelihood assets influence the type of livelihood strategy chosen by a household. Natural assets, physical assets, human assets, financial assets and social assets influence the selection of livelihood strategies of households in different ways and to a varying degree due to being very different types of livelihood assets [12]. Exogenous factors that influence the choice of livelihood strategy by households include the natural environment they are in as well as the policies and systems they are subject to. On the one hand, the natural environment they are in provides the selection of livelihood strategy with a material basis, on which their initial livelihood strategy is often strongly relied. To deal with the change in natural environment and to avoid loss or minimize loss, households often will change their original livelihood strategies [13,14]. On the other hand, policies and systems represented by an organizational structure, government policy, and community system lead the change in the livelihood strategy chosen by a household, and their influence on the choice of livelihood strategy is especially significant in underdeveloped areas [15]. For example, in northwest China, the implementation of policies like converting cultivated land into forest and returning grazing land to grassland leads to a decrease in the stock of natural assets owned by households by restricting their use of agricultural resources and prompts households to turn to non-agricultural livelihood activities, which results in a higher level of non-agriculturalization and diversification of livelihood [16,17].

In recent years, in the context of population increase and rapid economic growth, contradictions in aims between the population, resources, and ecological environment among nature reserves are increasingly intensified. In particular, with the gradual rise of rural tourism and leisure agriculture in China, the severity of irrational utilization of natural resource, destruction of ecological environment, and loss of biodiversity has exacerbated day by day [18,19,20]. Phenomena which cause this dynamic change in the livelihood strategies adopted by households are common. At the micro level of households, it is manifested as the change from a pure agricultural household to a part-time agricultural household or non-agricultural household, or the development process from a pure agricultural household to a major agricultural household or a professional agricultural household; at the macro level, it is manifested as a higher level of diversification and non-agriculturalization of the livelihood strategies adopted by households [9,21]. Therefore, focusing on and studying the choice of livelihood strategy by households among nature reserves and its influencing factors is of important theoretical and realistic significance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

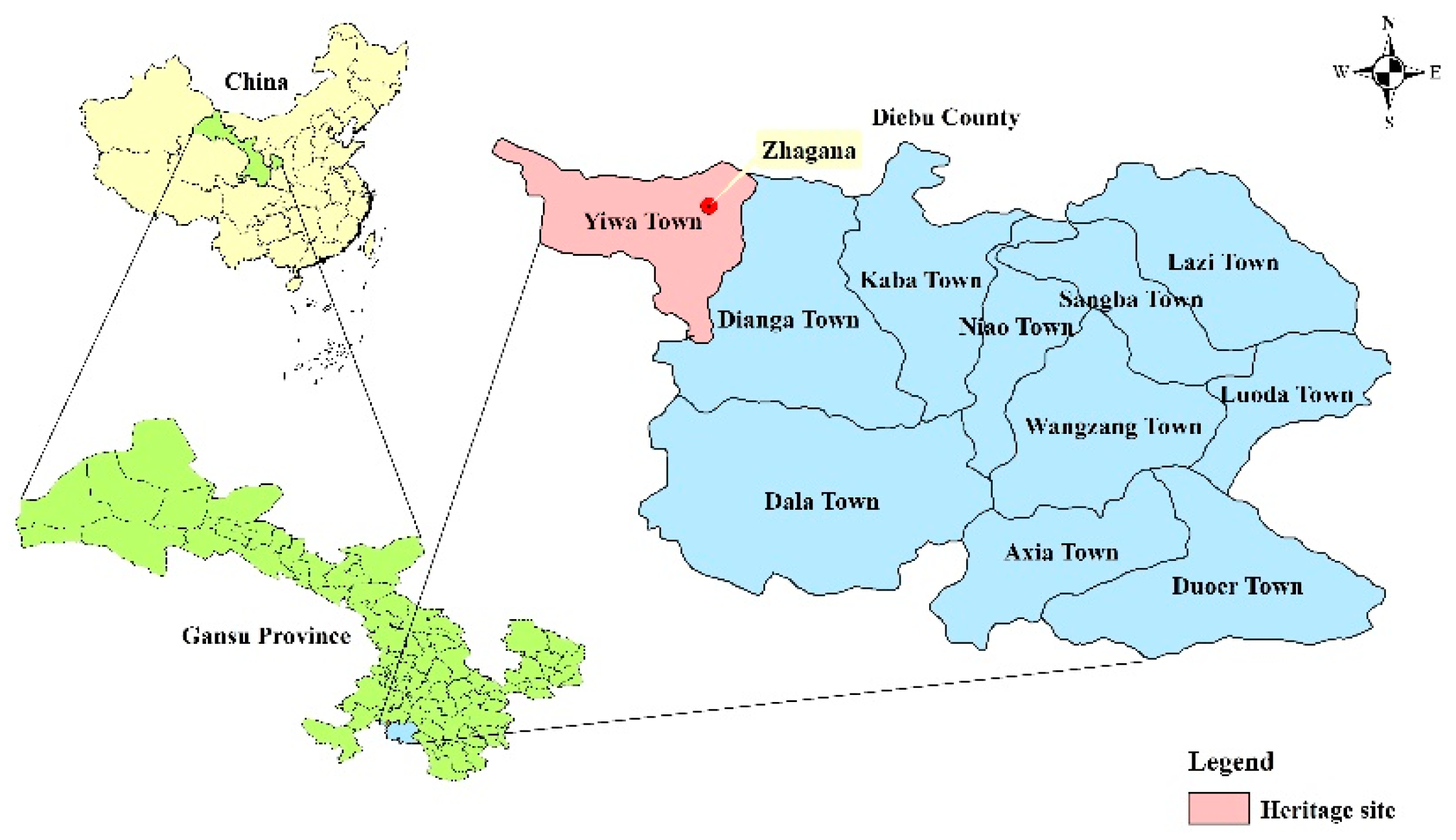

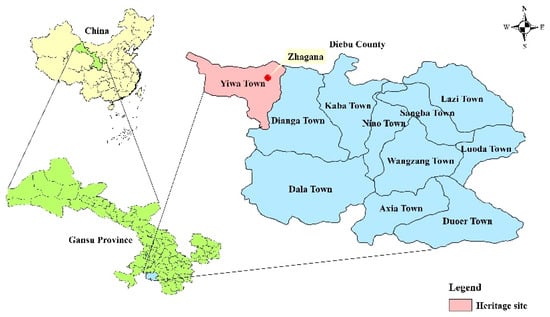

The unique geological history and diverse natural environment of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau have spawned many endemic and rare animal and plant species, forming a high-altitude ecosystem and species diversity center on the land. It is an important natural reserve in China and the world. Due to the vast territory and diverse natural and geographical conditions in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau area, there is a wide diversity of livelihood strategies adopted by households, including livestock breeding, crop cultivation, fruit picking, tourist reception, and becoming migrant workers. This paper selects Zhagana Village in Diebu County, Gansu Province, China, as the study area (Figure 1). This village is located in the eastern longitude of 103°08′49″–103°10′15″ and the northern latitude of 34°09′40″–34°10′80″.

Figure 1.

The location of the study area.

On the one hand, livelihood strategies adopted by households in Zhagana Village are diverse and are in the period of rapid change. Traditional livelihood strategies have been retained, such as an agricultural production strategy featuring a combination of long-standing plantation, forestry, and animal husbandry. In addition to the above, there are also non-agricultural production strategies like tourist reception and nonagricultural work, thereby providing the studies of livelihood strategies adopted by households with good empirical cases.

On the other hand, the core area of the Zhagana Agriculture-Forestry-Animal Husbandry Composite System (ZCS System), a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) site, is located in Zhagana Village. In 2002, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations launched the GIAHS protection initiative with an aim of exploring and conserving typical traditional agricultural systems worldwide. As a living heritage type, GIAHS is an important part of the global nature reserve system. As of the end of 2018, 57 traditional agricultural systems in 21 countries have been listed and included among the GIAHS sites [22]. As the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau’s first GIAHS site, the ZCS system is a compact and self-sufficient agricultural production system centering on the livelihood activity of household. More importantly, it is a typical example for the harmonized development between humans and nature, as well as for the sustainable development of human society.

For the above reasons, the selection of Zhagana Village for the case study of the livelihood strategies chosen by households in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is highly typical and representative.

2.2. Data Sources

This paper collected data by using a combination of questionnaire and Participatory Rural Appraisal [23] and designed a survey that revolved around the choice of livelihood strategy by households and its influencing factors. (1) The sources of income of households, including agricultural income and non-agricultural income. (2) Family characteristics of households, including population and location, as well as livelihood assets encompassing natural, physical, human, social, financial, cultural, and informational assets. (3) Households’ perception of, participation in, and satisfaction with main public policies. (4) Households’ perception of, response to, and severity evaluation of typical natural disasters.

The survey was conducted in October 2018 by surveying all the sampled households. Samples with obvious errors and incomplete information were removed. In the end, 154 households were taken as valid, accounting for 72.64% of all households in Zhagana Village.

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. The Classification Criteria of Livelihood Strategy

The type of livelihood strategy is a concrete manifestation of the livelihood strategy chosen by a household, and most scholars classify them by the standard of income [24,25,26]. In the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the sources of income of households can be divided into two types—agricultural income and non-agricultural income. Specifically, agricultural income includes crop cultivation, fruit picking, and livestock breeding. Non-agricultural income includes tourist reception, and becoming migrant workers [27]. Thus, this paper took the ratio of agricultural income to non-agricultural income of a household as the basis to classify livelihood strategies (Table 1).

Table 1.

The classification criteria of livelihood strategies.

2.3.2. The Influencing Factors and Analysis Indexes of Livelihood Strategy Choices

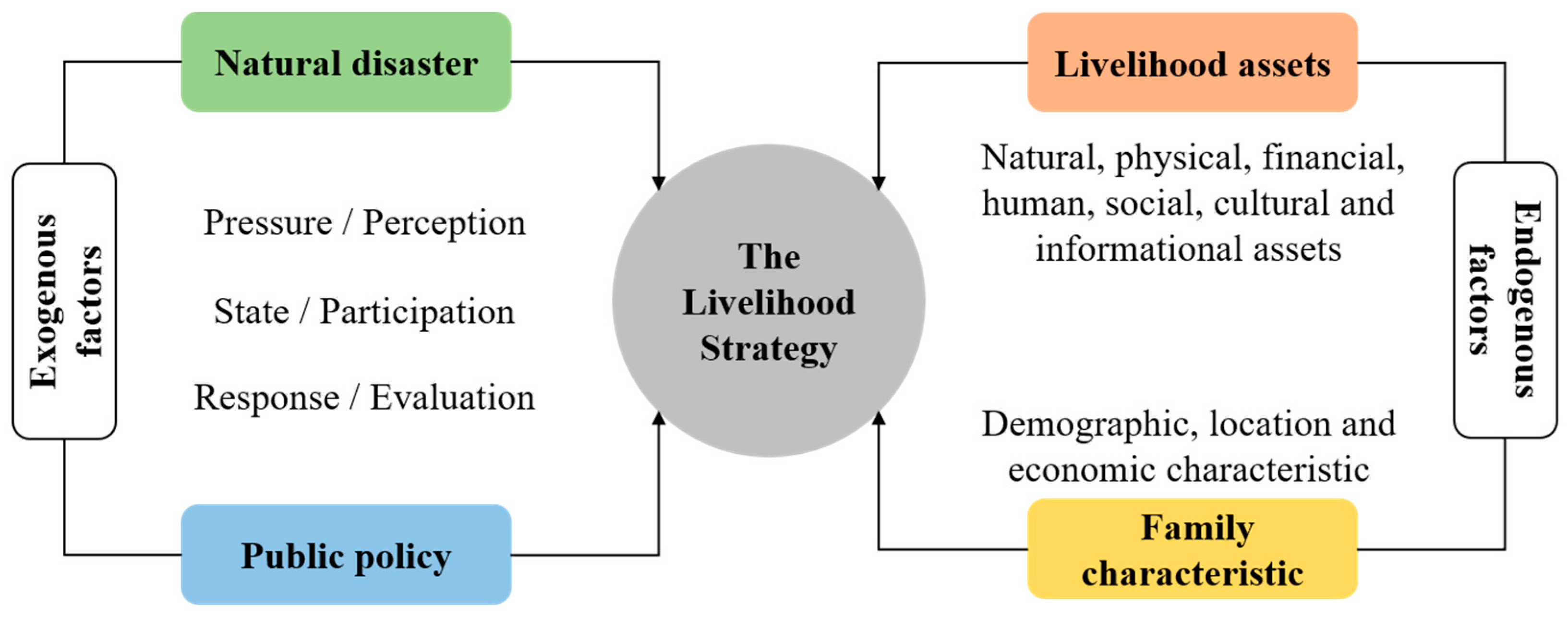

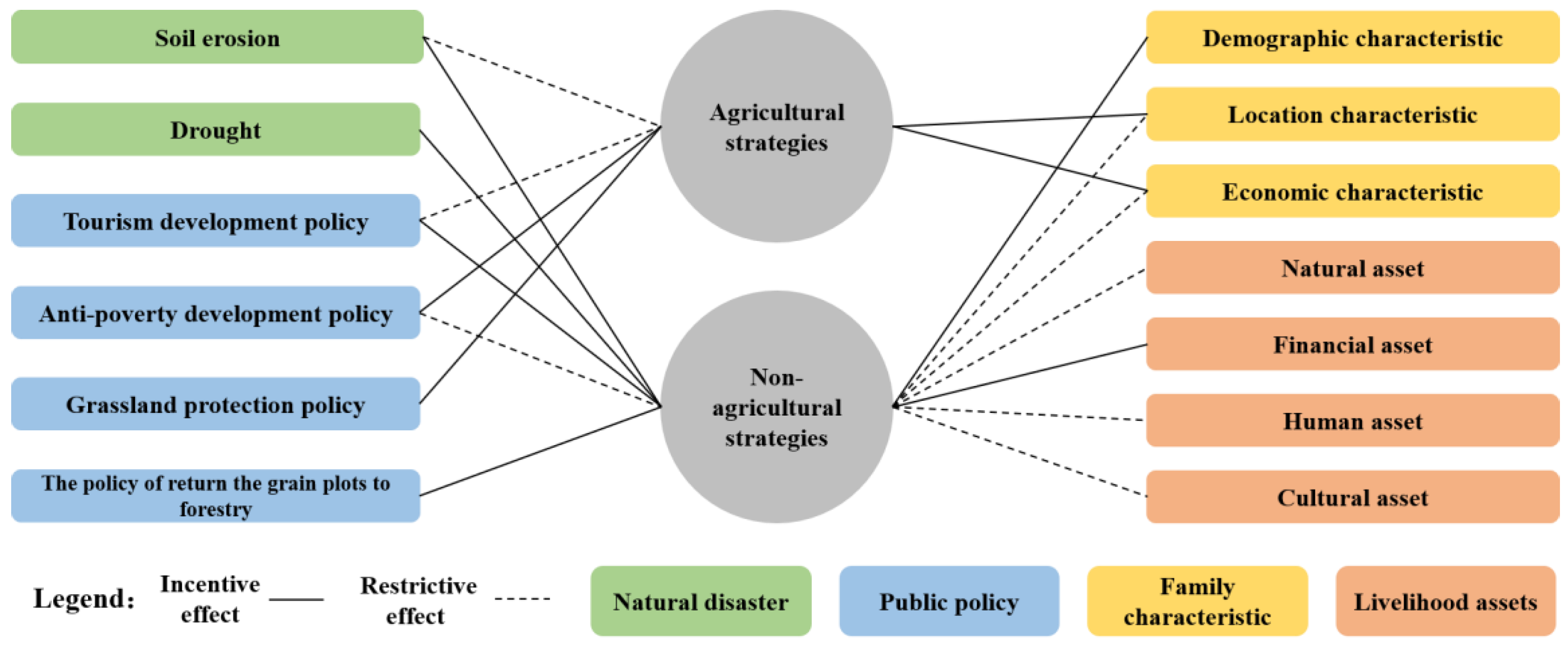

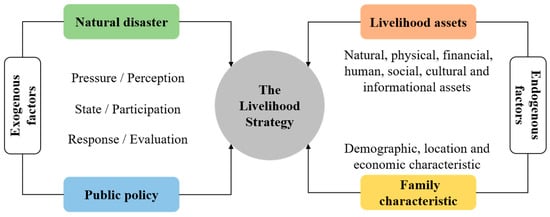

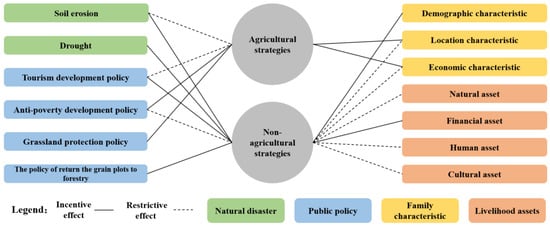

Many empirical studies show that factors influencing the choice of livelihood strategy by households can be divided into two types—exogenous factors and endogenous factors (Figure 2). Exogenous factors include the natural environment that households are in, as well as the policies and systems that they are subject to [28,29,30,31,32], while endogenous factors include livelihood assets and family characteristics of households [12,21].

Figure 2.

The analysis framework of influencing factors of farmers’ livelihood strategy choices.

1. Exogenous factors and their analysis indexes

Natural environment of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is fragile as a whole. Natural disasters like drought, flood, debris flow, and sand storm are frequent in Zhagana Village, which certainly will influence the choice of livelihood strategy by households. Through the scoring by representatives of households and experts, this paper selected drought, flood, and soil erosion for the analysis (Table 2). Among them, the soil erosion that this paper focuses on is caused by gravity erosion.

Table 2.

Indexes and descriptions of exogenous factors for livelihood strategy choice.

In the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, public policies that households are subject to can be divided into two kinds: one is incentive public policies represented by tourism development and industrial poverty alleviation, and this kind of policy tends to increase the economic income of households in the short term; the other kind is restrictive public policies, which include resettlement, converting cultivated land into forest, and returning grazing land to grassland. The latter policies often will cause a loss of economic income to households in the short term but will promote the diversification and non-agricultural development of the livelihood of households in the long term [33]. Through the scoring by representatives of households and experts, this paper chose tourism development policy and anti-poverty development policy to represent incentive public policies, while the policy of return the grain plots to forestry, grassland protection policy, and oilseed cultivation policy were selected from the restrictive public policy options (Table 2).

For the establishment of the index system, the Pressure-State-Response model [34] was used to divide the influence of a natural disaster or a public policy on a household into three dimensions for analysis, namely pressure and perception, state, and participation, as well as response and evaluation, with the sum of these three indexes taken as the evaluation score of the influence. The higher the evaluation score, the more susceptible a household is to the influence of this natural disaster or public policy; the lower the evaluation score, the less susceptible a household is to the influence of this natural disaster or public policy.

2. Endogenous factors and their analysis indexes

Based on the summary of previous studies [35], this paper set up a family characteristic index system consisting of demographic characteristics, location characteristics, and economic characteristics (Table 3), among which demographic characteristics were measured with age and gender of the head of household, health condition of the family members, and their level of education. Location characteristics were measured by the village which households live in. Economic characteristics were measured with the labor productivity of the agricultural activity that the household works on and the annual household net income.

Table 3.

Indexes and descriptions of endogenetic factors for livelihood strategy choice.

Households in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau have developed and accumulated abundant traditional knowledge during their long process of producing and living in the area. Meanwhile, with the all-round popularization of the Internet and rapid growth of mobile Internet, channels for households to receive new agricultural technology and knowledge are constantly being broadened. For example, Zhagana Village has a unique Tibetan Buddhist culture as well as local rules and conventions. In addition, in regards to long-term labor practices, the system of shifting agriculture and fallow, compost techniques, and so forth were also developed locally. In addition, the level of Internet penetration among families in this village is 97% and the number of residents aged over 20 who have smartphones accounts for 84.6% of the total population in the study area. Thus, this paper highlights the important role of traditional culture and information technology in livelihood strategies for households in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau area. Based on the livelihood assets evaluation system in the Sustainable Livelihood Approach set up by the DFID [7], the livelihood assets of a household are divided into seven types—natural, physical, financial, human, social, cultural, and informational assets. The positive range method was adopted to conduct the standardized processing of data [36] concerning these seven livelihood assets indexes (Table 3).

2.3.3. The Analysis Model of Driving Factors for Livelihood Strategy Choices

In consideration of the differences in dimensions between natural disaster factor index, public policy factor index, and family characteristic factor index constructed in this paper, as well as the possible correlations between them in the same period, this paper employed the Seemingly Unrelated Regressions (SUR Model) for parameter estimation [37]. The SUR Model can identify the correlations between random error terms of various factors and obtain estimated values of model parameters with smaller variance, with more valid estimates. It is one of the most important methods used to analyze and select influencing factors [38]. Software StataMP 14 was used, and the model is as follows:

In a regression equation system consisting of M regression equations, the ith equation satisfies:

where is the ith livelihood strategy chosen by the household at present; is the observed value of the jth influencing factor index; and are the regression coefficient equations; is the residual error.

3. Results

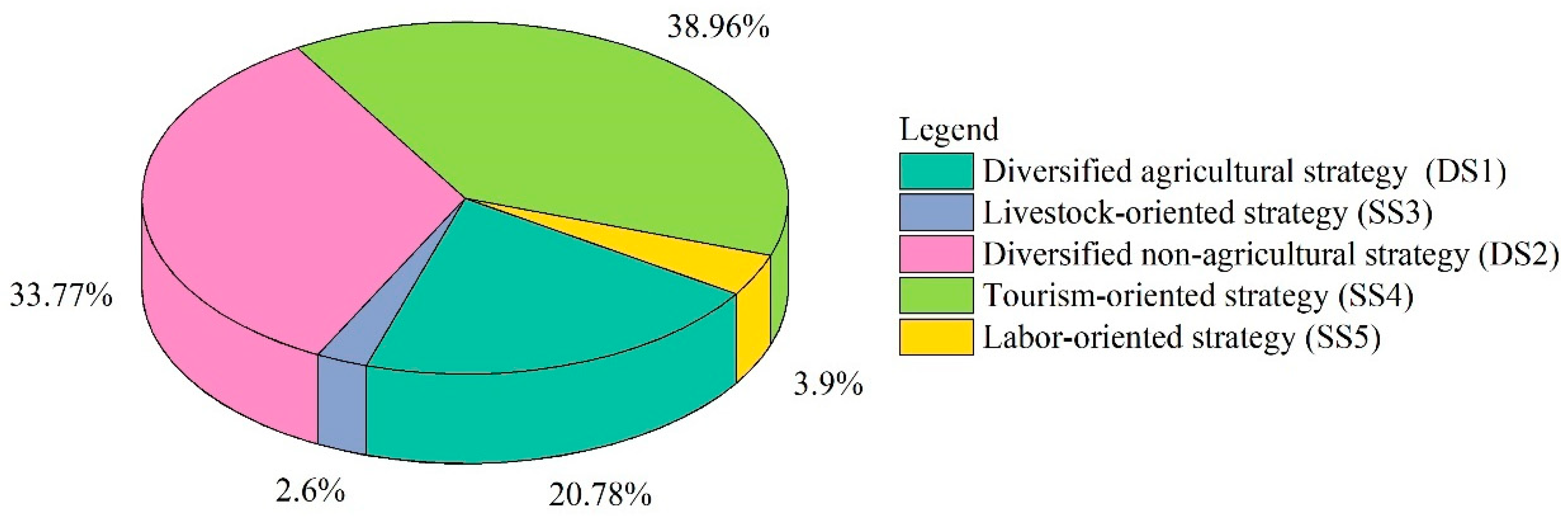

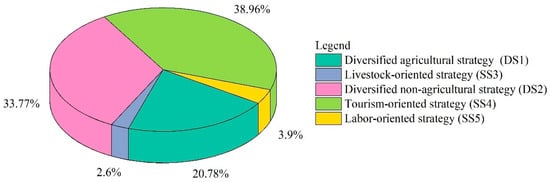

3.1. The Result of the Choices of Livelihood Strategies

Among 154 households who were surveyed in Zhagana Village, only 36 used the selected agricultural strategies, taking up 23.38% of the total number of samples. 118 chose non-agricultural strategies, accounting for 76.62% of the total number of samples (Figure 3). On the whole, households in Zhagana Village mostly chose a diversified agricultural strategy (DS1), diversified non-agricultural strategy (DS2), or tourism-oriented strategy (SS4), only a few chose a livestock-oriented strategy (SS3) or labor-oriented strategy (SS5), and no household chose a plantation-oriented strategy (SS1) or forestry-oriented strategy (SS2).

Figure 3.

The proportion of different types of farmers.

This result indicates that in the study area, as tourism gradually grows, more and more households begin to choose to work on tourist reception, leading to a higher level of part-time agriculturalization and non-agriculturalization of the livelihood strategies adopted by households. Meanwhile, most households who persist in agricultural production also adopt a diversified agricultural strategy which integrates plantation, forestry, and animal husbandry.

3.2. The Analysis Results of Exogenous Factors

3.2.1. The Influence of Natural Disasters on Farmers’ Livelihood Strategy Choices

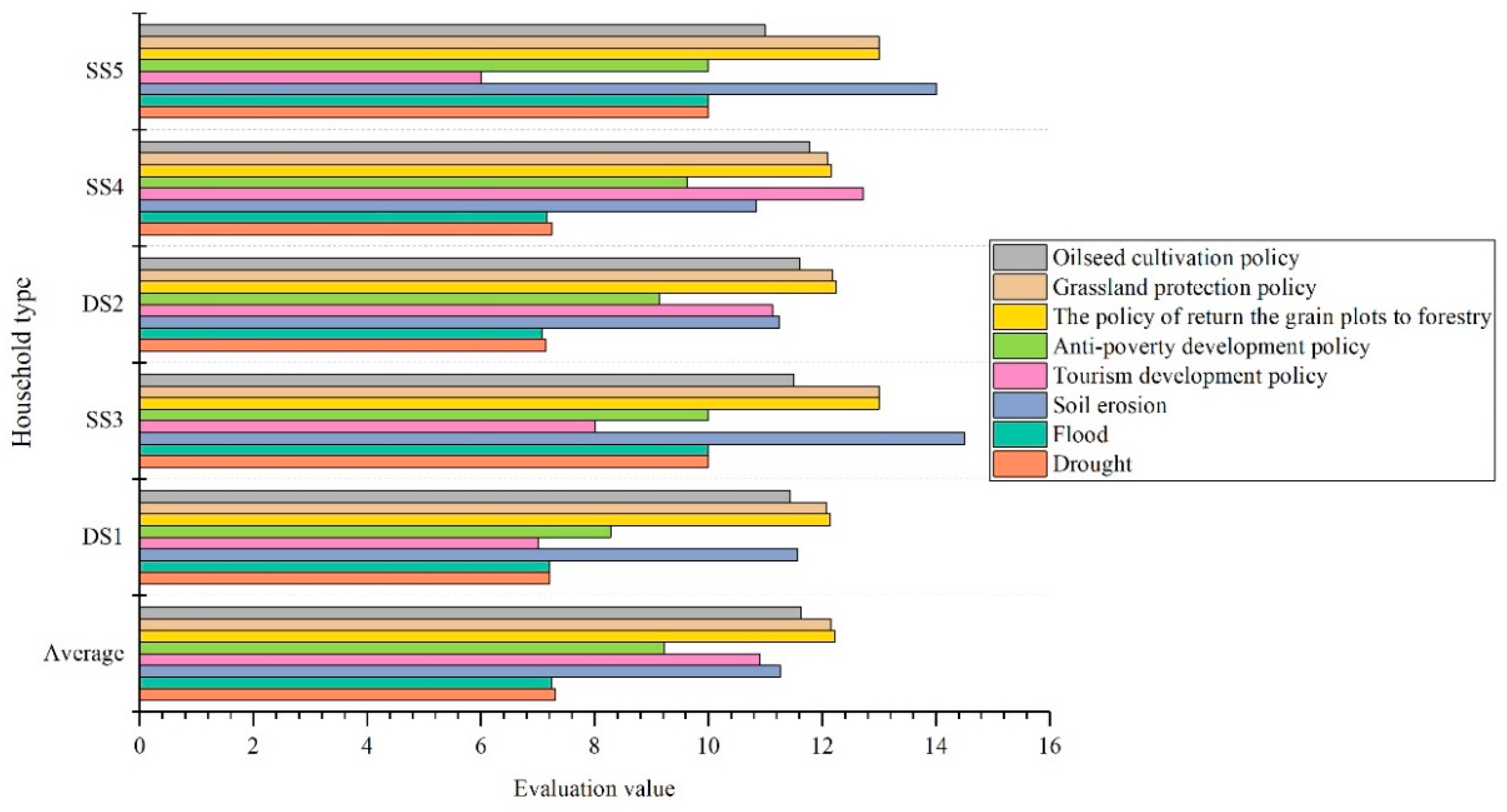

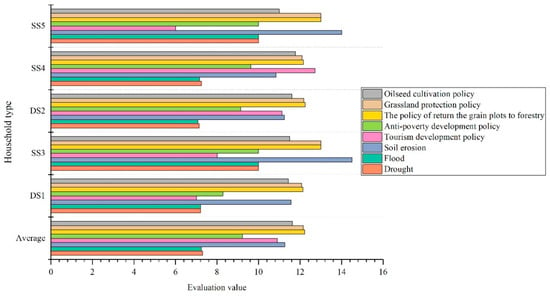

As a whole, ranking the evaluation by the households in the ZCS system, from high to low, on the influence of the three kinds of natural disasters, we have: soil erosion (11.26) > drought (7.31) > flood (7.24). This shows that households generally think that Zhagana Village is facing serious soil erosion, while flood and drought problems are perceived to be less severe.

The results of general statistical analysis show that different types of households are susceptible to the impact of natural disasters to a varying degree. Households who chose SS3 and SS5 are more susceptible to the impact of natural disasters, while households who selected DS2 and SS4 are less responsively affected by the impact of natural disasters (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The evaluation value of the indexes of exogenous factors.

The results of the analysis on the correlation between natural disaster factors and the selection of livelihood strategy show (Table A1) that N3(+), N7(−/+) and N8(−/+) among all the natural disaster factors, are significantly correlated with the choice of livelihood strategy of households. Specifically, the more insensitive is a household is to soil erosion, the more likely they will choose an agricultural production strategy; the more susceptible a household is to soil erosion or drought, the more likely they will choose a non-agricultural production strategy.

It shows that natural disaster influences the choice of livelihood strategy by households in a complex way, and different types of natural disaster influence the selection of livelihood strategy of household differently. On the whole, the soil erosion is the kind of natural disaster that has a significant influence on the selection of livelihood strategy of household, and it exert its influences through the household’s pressure/perception, or state/participation.

3.2.2. The Influence of Public Policies on Farmers’ Livelihood Strategy Choices

As a whole, the evaluation score of the influence of tourism development policy and anti-poverty development policy by households in the system was 10.90 and 9.22, respectively. Ranking the evaluation score of the influence of three kinds of restrictive policy from high to low, we have: the policy of returning the grain plots to forestry (12.22) > grassland protection policy (12.15) > oilseed cultivation policy (11.63). It follows that households generally believe that tourism development policy and the policy of returning the grain plots to forestry are two kinds of public policies that have a significant influence on livelihood choices, while anti-poverty development policy and oilseed cultivation policy have a weaker influence.

The results of general statistical analysis show that different types of households are susceptible to the impact of incentive and restrictive policies to a varying degree. SS4 households are the most sensitive to the incentive policy, SS3 households are most sensitive to the restrictive policy, and DS1 households are the least responsively affected by the restrictive policy (Figure 4).

The results of the analysis on the correlation between public policy factors and the selection of livelihood strategy (Table A1) show that P1(−/+), P2(−/+), P3(−/+), P5(+), P6(−), P7(+), P8(+), P10(+), and P11(+) among all the public policy factors, are the most significantly correlated with the choice of livelihood strategy by households.

Among the incentive policies, the more susceptible households are to the influence of anti-poverty development policy, or the less sensitive they are to the influence of tourism development policy, the more likely they will choose an agricultural production strategy; the more susceptible households are to the influence of tourism development policy or the less sensitive they are to the influence of anti-poverty development policy, the more likely that they would choose a non-agricultural production strategy. It follows that the two kinds of incentive policy will exert an influence on the choice of livelihood strategy by a household to a varying degree, among which tourism development policy has a more significant influence.

Among the restrictive policies, the more susceptible households are to the influence of the policy of returning the grain plots to forestry, the more likely that they would choose a non-agricultural production strategy; the more susceptible households are to the influence of a grassland protection policy, the more likely that they would choose an agricultural production strategy. It follows that the policy of returning the grain plots to forestry and grassland protection policy are two main kinds of restrictive policies that exert a significant influence on the choice of livelihood strategy made by a household through the pressure/perception and state/participation of households. However, since this kind of policy is somewhat necessary in the implementation process, there is no great difference between its influences on the choice of livelihood model made by different types of households.

3.3. The Analysis Results of Endogenous Factors

3.3.1. The Influence of Family Characteristics on Farmers’ Livelihood Strategy Choices

In Zhagana Village, the average age of the heads of households is 42.04, and most of the heads are male. Moreover, their family members are generally in good physical condition, have received 7.25 years of education, and live in low-altitude areas with an average annual net income of around 99,000 yuan, with a 31.23% labor productivity in agricultural activity.

General statistical results show that among households who chose agricultural production strategies, the DS1 households are concentrated in mid-altitude areas in the system, and most of the heads of these households are older men who have received some degree of education, and their families have a salient advantage in quantity of labor force and physical condition but a lower level of both household income and labor productivity in agricultural production. SS3 households are concentrated in higher-altitude areas in the system, most of the heads of these households are less-educated older women, and their families usually have a lower workforce level and poorer physical condition, but a higher level of family income and the highest level of labor productivity in agriculture.

Among the households who chose non-agricultural production strategies, DS2 households are concentrated in areas with convenient transportation and beautiful landscape in the system, whose heads are mostly younger men and families do not have an advantage in workforce level and physical condition but have a higher level of both family income and labor productivity in agricultural production. SS4 households are concentrated in areas with convenient transportation and beautiful landscapes in the system, whose heads are mostly better-educated men. These families do not have an obvious advantage in their workforce level but are in good physical condition with the highest level of family income and the lowest level of labor productivity in agricultural production. SS5 households are concentrated in lower-altitude areas in the system, whose heads are mostly less-educated younger men. These families do not have a marked advantage in their workforce level but have a great advantage in overall physical condition with the lowest level of family income and a higher level of labor productivity in agricultural production.

The results of the analysis of the correlation between family characteristic factors of households and the selection of livelihood strategy (Table A2) show that F4(+), F5(+/−) and F7(+/−) among family characteristic factors are significantly correlated with the selection of a livelihood strategy by households. The greater the advantage in location and economy a household has, the more likely that they would choose an agricultural production strategy; the greater the advantage in demographic characteristics a household has or the greater their disadvantage in location and economy, the more likely that they would choose a non-agricultural production strategy. It follows that the location characteristic and economic characteristic are the family characteristic factors that have the most significant influence on the selection of livelihood strategies by households.

3.3.2. The Influence of Livelihood Assets on Farmers’ Livelihood Strategy Choices

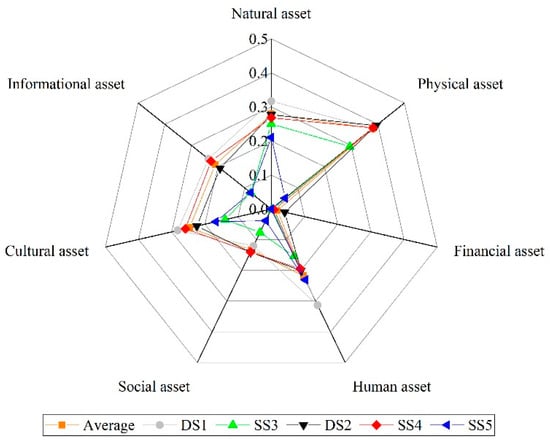

In the study area, the average score of livelihood assets of the households is 1.48, among which physical asset has the highest score, followed by natural, cultural, human, informational, and social assets, and ending with financial assets with the lowest score.

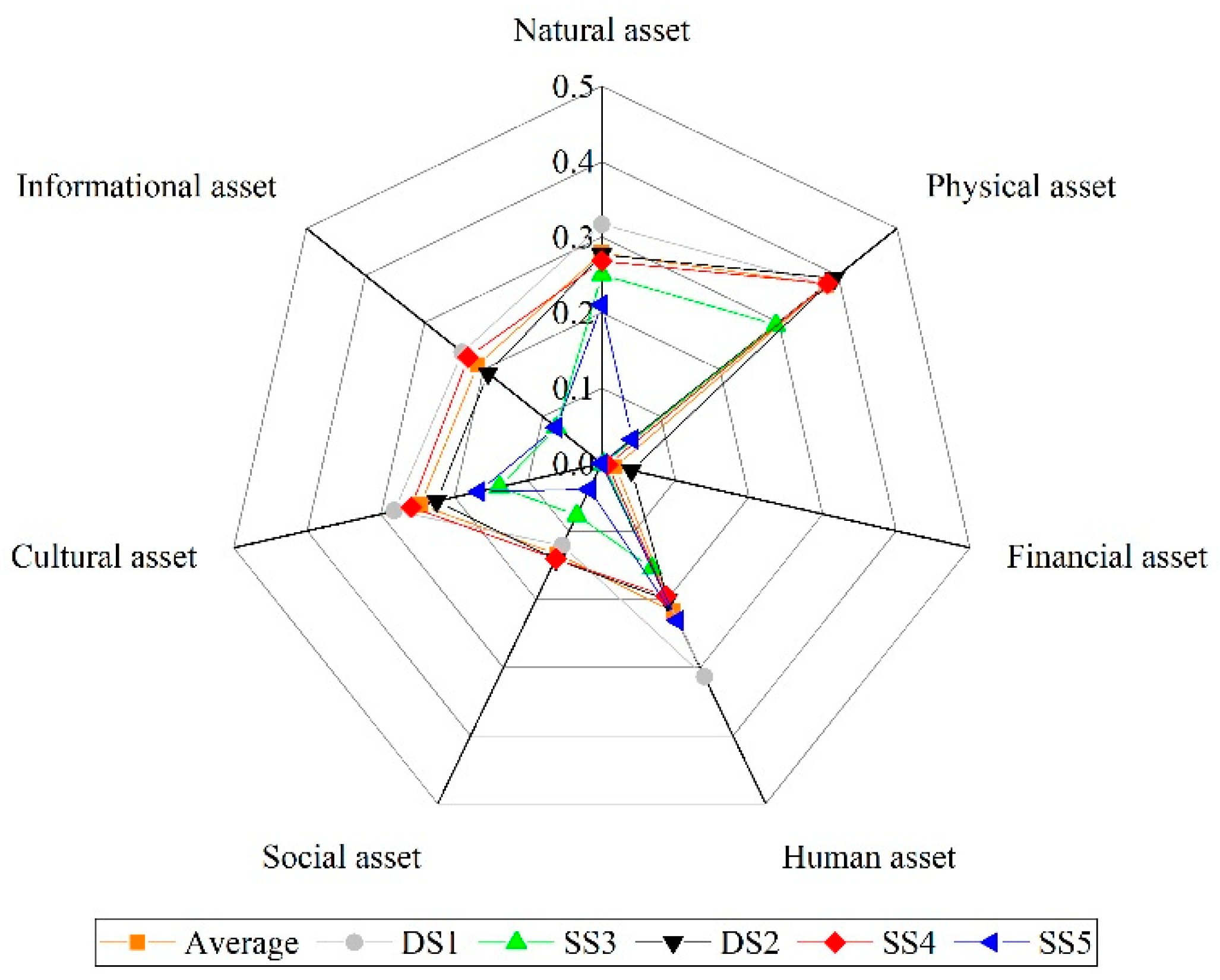

The results of general statistical analysis show that DS1 households have an obvious advantage in natural, human, cultural, and informational assets, yet have a comparative disadvantage in financial assets. SS3 households have an obvious advantage in financial, human, cultural, and informational assets. DS2 households have an obvious advantage in physical, financial, and social assets. SS4 households have an obvious advantage in social assets. SS5 households have an obvious advantage in natural, physical, financial, social, and informational assets (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The livelihood assets linked to different types of livelihood strategies.

The results of the analysis on the correlation between livelihood asset factor and the selection of livelihood strategy (Table A2) show that A1(−), A3(+), A4(−), and A6(−) among the livelihood asset factors, are significantly correlated with the selection of livelihood strategies by households. This means that a household is more likely to choose a non-agricultural production strategy if one of the following conditions is satisfied: a lower level of natural assets owned by the household; a higher level of financial assets; a lower level of human assets; a lower level of cultural assets. This conclusion is basically consistent with general statistical results about the level of households.

It follows that natural, cultural, financial, and physical assets have a significant influence on the selection of non-agricultural production strategies of households. Natural, human, and cultural assets are highly correlated with agricultural production activity and as a result, the lack of these three kinds of asset prompts households to turn to a non-agricultural production strategy. Meanwhile, sufficient financial assets prompt households to own more financial and human resources. As a result, households prefer other non-agricultural production activities rather than agricultural production.

3.4. The Driving Mechanism of Farmers’ Livelihood Strategy Choices

The results of the empirical analysis show that in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau area, the choice of livelihood strategy made by a household is influenced by both the endogenous factors like public policy and natural disaster, as well as the exogenous factors like family characteristic and livelihood assets (Figure 6). When a household is choosing an agricultural production strategy, soil erosion (−), among the natural disasters, will exert a significant influence; tourism development policy (−), anti-poverty development policy (+), and grassland protection policy (+), among the public policies, will exert a significant influence; location characteristic (+) and economic characteristic (+), among the family characteristics, will have a marked influence. When a household is choosing a non-agricultural production strategy, the natural disasters soil erosion (+) and drought (+) will exert a significant influence; among the public policies tourism development policy (+), anti-poverty development policy (−), and the policy of returning the grain plots to forestry (+), would have a significant influence; among the family characteristics, demographic characteristics (+), location characteristics (−), and economic characteristic (−) would have an obvious influence; among the livelihood assets, natural asset (−), financial asset (+), human asset (−), and cultural asset (−), would exert a prominent influence.

Figure 6.

The schematic diagram of farmers’ livelihood strategy choice mechanism.

On the whole, when a household is choosing between agricultural production strategies and non-agricultural production strategies, soil erosion, tourism development policy and anti-poverty development policy, as well as location characteristics and economic characteristics will all exert a significant influence to a varying degree (Figure 6). Specifically, the less insensitive a household is to soil erosion or tourism development policy, the more susceptible they are to anti-poverty development policy. In addition, the greater their advantage in location, or the higher their labor productivity in agricultural activity, the more likely that they would choose an agricultural production strategy. Otherwise, they would resort to a non-agricultural production strategy. It follows that the soil erosion as well as the tourism development policy are not only the two main restrictive factors that drive the households to choose an agricultural production strategy, but also the main incentive factors that prompt the households to choose a non-agricultural production strategy. Meanwhile, anti-poverty development policy, location characteristics, and economic characteristics are incentive factors that encourage households to choose an agricultural production strategy, as well as the restrictive factors that lead households to choose a non-agricultural production strategy.

4. Discussion

Due to limitations in data sources and research areas, the present study can be further explored and expanded in many aspects: (1) The influencing factors and analysis indexes of livelihood strategy choices were defined to focus on screening the factors that significantly affect the farmers’ choice. The present study reflects a unidirectional relationship between the four factors (including natural disasters, public policies, livelihood assets, and family characteristics) and the farmers’ choice of livelihood strategies, but fails to analyze the subsequent effect of changed livelihood strategies on the factors. Indeed, the farmers’ choice of livelihood strategies has a complex correlation with its influencing factors. Such a correlation should be fully demonstrated in future research. (2) The analysis model of driving factors for livelihood strategy choices were mainly based on correlation analysis. The influencing factors were screened and determined. The methods such as causal analysis or scenario analysis shall be integrated in future research to build a more comprehensive influencing mechanism for farmers’ choices of livelihood strategies. (3) The case study of Zhagana Village has limitations in data. Since the research cycle is too short, the data type is cross-section data, making it impossible to perform panel data analysis through a long time series. In addition, due to the lack of fully-sampled surveys and the comparison with external areas of the study area, the transformation of farmers’ livelihood strategies in the area of case study was not demonstrated from a macro perspective. Therefore, the time span, sample size, area, and scope of the survey shall be expanded in the follow-up study.

Many empirical studies argue that in the process of changing from a traditional agriculture-centered livelihood strategy to a part-time agricultural and non-agricultural livelihood strategy, households adapt their production behavior and lifestyle accordingly, for example, a household’s degree of dependence, utilization methods, and utilization efficiency of natural resources like land resource and water resource change [39,40]; the types of energy consumed by households and ways of using energy change [41,42]; the layout of settlements in villages and community relations also change accordingly [43]. These changes in turn result in changes in their ecological environment.

Compared with the agricultural production strategies, choosing a non-agricultural production strategy has an obvious advantage as it normally can bring a higher level of economic income to households. However, non-agricultural production strategies, represented by a tourism-oriented strategy, may pose a great threat to fragile natural and geographical conditions in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau area. Specific manifestations include:

- Discontinued farming is increasingly aggravated. The average area of land cultivated by households who choose non-agricultural production strategies is 0.420 ha. The average area of land cultivated by households in Zhagana Village is 0.432 ha, and the average area of land cultivated by households who choose agricultural production strategies is 0.458 ha. The reason behind the differences in the area of cultivated land is that households who choose a non-agricultural production strategy abandon more cultivated land. On the one hand, staple crops like highland barley are normally harvested in August to September every year, coinciding with local peak tourist season. As a result, the opportunity cost for this type of household to harvest crops in the peak tourist season increases gradually, so they choose to abandon some cultivated land. On the other hand, the overall conditions for cultivation in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau are unfavorable, so to save time, this type of household tends to choose more cost-effective and less time-consuming ways of cultivating crops, leading to an exponential increase in the usage of insecticide and other agrochemicals [44], thus leading to lower soil fertility of cultivated land.

- Environmental cost of energy consumption rises. In the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, three types of energy are commonly used by households, namely traditional energy, commodity energy, and new energy. Specifically, traditional energy includes fuel wood, straw, and animal manure; commodity energy features coal, electricity, liquefied gas, and gasoline; new energy features solar energy. Households who choose a non-agricultural production strategy are more reliant on commodity energy and less reliant on traditional energy in terms of energy consumption. In particular, households who choose a tourism-oriented strategy cause a substantial increase in the consumption of liquefied gas and gasoline because they need to provide tourists with catering and transportation services. Furthermore, the average consumption of liquefied gas and gasoline per household is 79.24 kgce/a and 194.24 kgce/a, respectively. Average consumption of liquefied gas and gasoline per household among households in Zhagana Village is 53.29 kgce/a and 127.98 kgce/a, respectively, the average consumption of liquefied gas and gasoline per household among households who chose an agricultural production strategy is 32.16 kgce/a and 31.76 kgce/a, respectively. However, the consumption of these two kinds of energy will bring massive greenhouse gas emissions and lead to a significant increase in environmental cost of energy consumption.

Along with the continuous development of the natural environment and social economy, the empirical analysis of this paper indicates that the trend of the farmers towards non-agricultural strategies is very significant. However, it is vital to keep the sustainable development of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau in the transformation process of farmers’ livelihood strategies. This paper reckons that the farmers’ livelihood strategies in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau should meet the basic requirements of natural sustainability and social sustainability. Specifically, this livelihood strategy can maintain the income status of farmers at a high level for a long time. Meanwhile, the livelihood strategy has a low influence on environmental costs such as the consumption of natural resources like land, as well as energy consumption. Based on this standard, a diversified non-agricultural strategy (DS2) such as one inclusive of tourism reception and other non-agricultural activities would remain in line with the demands of livelihood strategies. Compared with specializing livelihood strategies, many studies have also confirmed that diversified livelihood strategies can effectively increase farmers’ income and reduce the impoverished population in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau [45]. On account of the empirical analysis results of this paper, efforts should be made to promote farmers’ shift to sustainable livelihood strategies by establishing a moderate tourism development policy, decreasing the difficulty of obtaining loans, improving the labor productivity of farmers engaged in non-agricultural activities, and so on. Therefore, it is important to encourage more farmers to choose a diversified non-agricultural strategy.

5. Conclusions

Based on the summary of previous studies, this paper constructed a model for analyzing influencing factors on the choice of livelihood strategy by households in a nature reserve. It also conducted an empirical study on the choice of livelihood strategies by households in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau area, and drew the following conclusions:

- Our model for analyzing influencing factors on the choice of livelihood strategy by households covered exogenous factors and endogenous factors. Exogenous factors contained natural disasters and public policies. The impact of such factors on farmers were measured and analyzed using three dimensions: pressure and perception, state and participation, response and evaluation. Endogenous factors contained family characteristics and livelihood assets. Family characteristics covered indicators such as demographic characteristics, location characteristics, and economic characteristics. Livelihood assets contained seven types of assets, including natural assets, physical assets, financial assets, human assets, social assets, cultural assets, informational assets.

- In the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau area, the source of income of a household can be divided into two types—agricultural income and non-agricultural income. Subsequently, livelihood strategies for households can be divided into two types—agricultural production strategies and non-agricultural production strategies. In Zhagana Village, only 36 households choose agricultural production strategies, accounting for 23.38% of the total number of samples. 118 households choose non-agricultural production strategies, taking up 76.62% of total number of samples. At present, non-agricultural production strategies, especially tourism-oriented strategy, is the primary type of livelihood strategy that households in Zhagana Village choose.

- In general, the transformation in farmers’ choice of livelihood strategies in Zhagana Village presents an irresistible trend. At the micro-level, farmers tend to choose non-agricultural production strategies. At the macro-level, farmers are diversified. Moreover, the transformation in farmers’ choice of livelihood strategies is caused by the combined effect of exogenous factors and endogenous factors rather than by a single factor. Among them, exogenous factors that influence the selection of a livelihood strategy by households mainly include the natural environment they are in and the policies and systems they are subject to, among which soil erosion and a tourism development policy are restrictive factors that drive households to choose an agricultural production strategy and the incentive factors that encourage household to choose a non-agricultural production strategy. In addition, anti-poverty development policy is an incentive factor that leads households to choose an agricultural production strategy and is a restrictive factor for households to choose a non-agricultural production strategy. This means the less sensitive a household is to soil erosion or tourism development policy, or the more susceptible they are to anti-poverty development policy, the more likely it is that they would choose an agricultural production strategy, otherwise the more likely they would choose a non-agricultural production strategy. Meanwhile, endogenous factors that influence the selection of livelihood strategy by households mainly include livelihood assets and family characteristics, among which location characteristic and economic characteristic are incentive factors that drive households to choose an agricultural production strategy and restrictive factors that encourage households to choose a non-agricultural production strategy. This means the greater the advantage in location that a household has or the higher the labor productivity of their family in agricultural activity, the more likely that they would choose an agricultural production strategy, otherwise the more likely that they would choose a non-agricultural production strategy.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. Conceptualization, L.Y. and Q.M.; methodology, L.Y. and M.L.; software, L.Y.; validation, L.Y., M.L. and Q.M.; formal analysis, L.Y.; investigation, L.Y.; resources, Q.M.; data curation, L.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Y.; writing—review and editing, L.Y., M.L. and Q.M.; visualization, L.Y.; supervision, M.L.; project administration, Q.M.; funding acquisition, Q.M.

Funding

This research and the APC were funded by National Key R&D Program of China, grant number 2017YFC0506402.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The correlation analysis of exogenous factors and farmers’ livelihood strategy choice.

Table A1.

The correlation analysis of exogenous factors and farmers’ livelihood strategy choice.

| Factor Type | Index Number | Agricultural Strategies | Non-Agricultural Strategies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS1 | SS3 | DS2 | SS4 | SS5 | |||||||

| Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | ||

| Drought | N1 | 0.067 | 0.613 | 1.283 | 0.805 | 0.860 | 0.627 | 0.893 | 0.731 | 1.869 | 0.621 |

| N2 | 3.143 | 0.115 | 9.622 | 0.449 | 0.974 | 0.960 | 0.498 | 0.175 | 12.361 | 0.330 | |

| N3 | 1.400 | 0.335 | 17.217 | 0.999 | 1.025 | 0.948 | 1.829* | 0.096 | 6.428 | 0.252 | |

| Flood | N4 | 0.099 | 0.451 | 3.358 | 0.346 | 0.741 | 0.370 | 0.927 | 0.833 | 1.005 | 0.997 |

| N5 | 0.201 | 0.162 | 16.307 | 0.337 | 0.533 | 0.107 | 0.677 | 0.303 | 15.496 | 0.275 | |

| N6 | 0.021 | 0.869 | 3.992 | 1.000 | 1.034 | 0.920 | 1.462 | 0.245 | 3.634 | 0.420 | |

| Soil erosion | N7 | −5.321 *** | 0.000 | −10.471 ** | 0.039 | 0.656 * | 0.061 | 0.309 *** | 0.000 | 0.385 | 0.240 |

| N8 | 0.247 * | 0.094 | 0.425 | 0.403 | 1.221 | 0.506 | 0.802 | 0.460 | 0.155 * | 0.087 | |

| N9 | 0.087 | 0.525 | 19.793 | 0.978 | 0.813 | 0.566 | 0.842 | 0.609 | 1.531 | 0.559 | |

| Tourism development | P1 | −1.714 *** | 0.002 | 1.144 | 0.802 | 3.980 *** | 0.000 | 5.788 *** | 0.000 | 1.270 | 0.758 |

| P2 | −0.304 *** | 0.000 | 2.454** | 0.017 | 4.109 *** | 0.000 | 5.376 *** | 0.000 | 2.004 | 0.175 | |

| P3 | −1.393 *** | 0.000 | 3.018 * | 0.054 | 1.879 ** | 0.015 | 7.282 *** | 0.000 | 8.280 *** | 0.001 | |

| Anti-poverty development | P4 | 0.008 | 0.915 | 1.013 | 0.983 | 0.833 | 0.553 | 1.143 | 0.672 | 0.325 | 0.430 |

| P5 | 0.074 | 0.248 | 4.838 *** | 0.004 | 0.888 | 0.689 | 1.511 | 0.171 | 1.881 | 0.182 | |

| P6 | 0.034 | 0.546 | 0.688 | 0.436 | 1.281 | 0.219 | 0.947 | 0.824 | −4.044 ** | 0.046 | |

| Return the grain plots to forestry | P7 | 0.217 | 0.234 | 5.880 | 0.990 | 1.230 | 0.499 | 1.011 | 0.911 | 10.718 * | 0.055 |

| P8 | 0.151 | 0.608 | 1.862 | 0.990 | 1.858 | 0.192 | 2.651 ** | 0.049 | 0.589 | 0.666 | |

| P9 | −0.353 | 0.155 | 0.788 | 0.836 | 0.678 | 0.394 | 0.483 | 0.102 | 1.316 | 0.867 | |

| Grassland protection | P10 | 1.429 *** | 0.006 | 3.531 | 0.991 | 0.695 | 0.349 | 0.539 | 0.104 | 5.294 | 0.186 |

| P11 | 0.671 ** | 0.021 | 1.356 | 0.992 | 1.713 | 0.321 | 2.435 | 0.120 | 1.569 | 0.991 | |

| P12 | 0.074 | 0.708 | 0.411 | 0.399 | 1.310 | 0.577 | 1.948 | 0.170 | 0.149 | 0.174 | |

| Oilseed cultivation | P13 | 0.086 | 0.665 | 2.351 | 0.994 | 1.321 | 0.446 | 1.534 | 0.257 | 3.324 | 0.248 |

| P14 | −0.091 | 0.801 | 2.713 | 1.000 | 1.252 | 0.713 | 1.267 | 0.712 | 8.916 | 0.991 | |

| P15 | 1.494 | 0.236 | 0.404 | 0.262 | 1.020 | 0.949 | 1.638 | 0.102 | 0.149 | 0.130 | |

| Constant | 5.841 | 0.832 | 19.382 | 0.487 | 2.763 | 0.568 | 1.090 | 0.961 | 2.268 | 0.349 | |

Note: *** represents 1% significance, ** represents 5% significance, * represents 10% significance.

Table A2.

The correlation analysis of endogenetic factors and farmers’ livelihood strategy choice.

Table A2.

The correlation analysis of endogenetic factors and farmers’ livelihood strategy choice.

| Factor Type | IndexNumber | Agricultural Strategies | Non-Agricultural Strategies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS1 | SS3 | DS2 | SS4 | SS5 | |||||||

| Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | ||

| Livelihood assets | A1 | −1.422 | 0.721 | −2.568 | 0.376 | −1.673 | 0.643 | −2.782 * | 0.058 | −1.619 ** | 0.040 |

| A2 | −15.505 | 0.365 | −1.775 | 0.343 | 1.333 | 0.493 | 0.127 | 0.935 | −0.581 | 0.725 | |

| A3 | 2.285 | 0.469 | 1.998 | 0.547 | 2.345 * | 0.073 | 2.204 *** | 0.008 | 0.947 | 0.791 | |

| A4 | −0.701 | 0.395 | 0.836 | 0.783 | −8.633 | 0.152 | −5.878 ** | 0.048 | 1.102 | 0.707 | |

| A5 | −3.37 | 0.695 | −2.452 | 0.714 | −3.927 | 0.642 | 4.232 | 0.46 | −0.186 | 0.975 | |

| A6 | −5.108 | 0.236 | −0.683 | 0.795 | −3.411 | 0.366 | −2.425 | 0.286 | −2.493 * | 0.083 | |

| A7 | 8.498 | 0.209 | −0.298 | 0.897 | −4.613 | 0.213 | −2.821 | 0.154 | −1.722 | 0.432 | |

| Demographic characteristic | F1 | 0.124 | 0.192 | 10.428 | 0.239 | 0.938 | 0.164 | 1.006 | 0.885 | 0.996 | 0.983 |

| F2 | 4.569 | 0.789 | 0.021 | 0.329 | 3.031 | 0.353 | 5.556 | 0.198 | 1.218 | 0.999 | |

| F3 | 6.670 | 0.987 | 60.934 | 0.121 | 0.806 | 0.663 | 0.997 | 0.994 | −0.500 | 0.104 | |

| F4 | 0.432 | 0.278 | 34.551 | 0.447 | 0.708 | 0.249 | 1.058 * | 0.076 | 0.008 | 0.997 | |

| Location characteristic | F5 | 1.879 | 0.326 | 0.356 * | 0.088 | −0.663 | 0.195 | −0.661 ** | 0.018 | 0.509 | 0.101 |

| Economic characteristic | F6 | 3.947 | 0.293 | 4.27 | 0.285 | 3.993 | 0.316 | 3.967 | 0.303 | 0.722 | 0.874 |

| F7 | 3.419 * | 0.087 | 1.622 | 0.349 | −2.561 * | 0.054 | −1.259 * | 0.078 | 2.575 | 0.139 | |

| Constant | 17.763 | 0.201 | 1.723 | 0.218 | 17.093 * | 0.059 | 1.724 | 0.880 | 2.352 | 0.551 | |

Note: *** represents 1% significance, ** represents 5% significance, * represents 10% significance.

References

- Kates, R.W.; Clark, W.C.; Corell, R.; Hall, J.M.; Jaeger, C.C.; Lowe, I.; McCarthy, J.J.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; Bolin, B.; Dickson, N.M.; et al. Sustainability Science. Science 2001, 292, 641–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Liu, M.C.; Min, Q.W.; Li, W.H. Specialization or Diversification? The Situation and Transition of Households’ Livelihood in Agricultural Heritage Systems. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2018, 16, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.R.; Venter, O.; Fuller, R.A.; Allan, J.; Maxwell, S.L.; Negret, P.J.; Watson, J.E.M. One-third of global protected land is under intense human pressure. Science 2018, 360, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Huang, L.; Xiao, T.; Wu, D. Effects of Human Activities on the Ecosystems of China’s National Nature Reserves. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 39, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F.; Xu, Z.M.; Shang, H.Y. An Overview of Sustainable Livelihoods Approach. Adv. Earth Sci. 2009, 1, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, F. Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. J. Dev. Stud. 1998, 35, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DFID. DFID Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; Department for International Development: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G.R. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; IDS Discussion Paper No. 296; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.F.; Zhao, X.Y. A Review of Ecological Effect of Peasant’s Livelihood Transformation in China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2015, 35, 3157–3164. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, C.M.; Shackleton, S.E.; Buiten, E.; Bird, N. The importance of dry woodlands and forests in rural livelihoods and poverty alleviation in South Africa. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F. Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Developing Countries; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.F.; Chen, Q.R.; Xie, H.L. Influence of the Farmer’s Livelihood Assets on Livelihood Strategies in the Western Mountainous Area, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.M.; Bosch, O.J.; Nguyen, N.C.; Trinh, C.T. System dynamics modelling for defining livelihood strategies for women smallholder farmers in lowland and upland regions of northern Vietnam: A comparative analysis. Agric. Syst. 2017, 150, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, K.; Zabbey, N. Contaminated land and wetland remediation in Nigeria: Opportunities for sustainable livelihood creation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 639, 1560–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, X.; Pouliot, M.; Walelign, S.Z. Livelihood Strategies and Dynamics in Rural Cambodia. World Dev. 2017, 97, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y. Environmental Perception of Farmers of Different Livelihood Strategies: A Case of Gannan Plateau. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2012, 32, 6776–6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Li, W.; Yang, P.T.; Liu, S. Impact of Livelihood Capital on the Livelihood Acitivties of Farmers and Herdsmen on Gannan Plateau. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2011, 4, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Bai, X.Z.; Huang, R.Q. The Impact of Global Warming on Vegetation Resources in the Hinterland of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Nat. Resour. 2004, 19, 331–336. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R. Rangeland degradation on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau: A review of the evidence of its magnitude and causes. J. Arid. Environ. 2010, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shijin, W.; Lanyue, Z.; Yanqiang, W. Integrated risk assessment of snow disaster over the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2019, 10, 740–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Lun, F.; Min, Q.; Zhang, C.; Li, H. Livelihood Assets and Strategies among Rural Households: Comparative Analysis of Rice and Dryland Terrace Systems in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. GIAHS around the World. Available online: http://www.fao.org/giahs/giahsaroundtheworld/en/ (accessed on 31 July 2019).

- Chambers, R. The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal. World Dev. 1994, 22, 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.R.; Little, P.D.; Mogues, T.; Negatu, W. Poverty Traps and Natural Disasters in Ethiopia and Honduras. World Dev. 2007, 35, 835–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafongoya, P.; Mubaya, C.P. Local-level climate change adaptation decision-making and livelihoods in semi-arid areas in Zimbabwe. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 19, 2377–2403. [Google Scholar]

- Perge, E.; Mckay, A. Forest Clearing, Livelihood Strategies and Welfare: Evidence from the Tsimane’ in Bolivia. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 126, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Lun, F.; Min, Q.; Li, W. The impacts of farmers’ livelihood capitals on planting decisions: A case study of Zhagana Agriculture-Forestry-Animal Husbandry Composite System. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walelign, S.Z. Livelihood Strategies, Environmental Dependency and Rural Poverty: The Case of Two Villages in Rural Mozambique. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 18, 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musinguzi, L.; Efitre, J.; Odongkara, K.; Ogutu-Ohwayo, R.; Muyodi, F.; Natugonza, V.; Olokotum, M.; Namboowa, S.; Naigaga, S. Fishers’ Perceptions of Climate Change, Impacts on Their Livelihoods and Adaptation Strategies in Environmental Change Hotspots: A Case of Lake Wamala, Uganda. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 18, 1255–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, C.; Garcia, M.; Gilles, J.; Pozo, O.; Yucra, E.; Rojas, K. Can Warmer Be Better? Changing Production Systems in Three Andean Ecosystems in The Face of Environmental Change. J. Arid Environ. 2017, 147, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korah, P.I.; Nunbogu, A.M.; Akanbang, B.A.A. Spatio-temporal dynamics and livelihoods transformation in Wa, Ghana. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Ahmed, M.; Ojea, E.; Fernandes, J.A. Impacts and responses to environmental change in coastal livelihoods of south-west Bangladesh. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 637–638, 954–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.C.; Zheng, D.S.; Jiang, J.J. Integrated Features and Benefits of Livelihood Capital of Farmers after Land Transfer Based on Livelihood Transformation. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2018, 134, 274–281. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfslehner, B.; Vacik, H. Evaluating sustainable forest management strategies with the Analytic Network Process in a Pressure-State-Response framework. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 88, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Lun, F.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Min, Q. An Analysis on Crops Choice and Its Driving Factors in Agricultural Heritage Systems—A Case of Honghe Hani Rice Terraces System. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.L.; Zhou, L.H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, G.J.; Zhao, M.M.; Wang, R. Impact of farmers’ livelihood capital on livelihood strategy in a typical desertification area in the inner mongolia autonomous region. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017, 37, 6963–6972. [Google Scholar]

- Donati, M.; Riani, M.; Verga, G.; Zuppiroli, M. The Impact of Investors in Agricultural Commodity Derivative Markets. Outlook Agric. 2016, 45, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susaeta, A.; Lal, P.; Carter, D.R.; Alavalapati, J. Modeling nonindustrial private forest landowner behavior in face of woody bioenergy markets. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 46, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Z.; Kong, X.B.; Xu, J.C. Farm Household Livelihood Diversity and Land Use in Suburban Areas of the Metropolis: The Case Study of Daxing District, Beijing. Geogr. Res. 2012, 31, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J.; Huang, Z.; Deng, H. Characteristics of nonpoint source pollution load from crop farming in the context of livelihood diversification. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lax, J.; Köthke, M. Livelihood Strategies and Forest Product Utilisation of Rural Households in Nepal. Small-Scale For. 2017, 16, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amare, D.; Mekuria, W.; Wondie, M.; Teketay, D.; Eshete, A.; Darr, D. Wood Extraction among the Households of Zege Peninsula, Northern Ethiopia. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 142, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majekodunmi, A.O.; Dongkum, C.; Langs, T.; Shaw, A.P.M.; Welburn, S.C. Shifting livelihood strategies in northern Nigeria—Extensified production and livelihood diversification amongst Fulani pastoralists. Pastoralism 2017, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.L.; Song, C.M.; Yu, Z.R.; Zhang, F.R. The Farm Household’s Choice of Land Use Type and Its Effectiveness on Land Quality and Environment in Huang-Huai-Hai Plain. J. Nat. Resour. 2014, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J.; Yu, C.; Li, M.; Wu, J. Patterns and dynamics of the human appropriation of net primary production and its components in Tibet. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 210, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).