Abstract

Built on the idea that supply chain integration (SCI) and green supply chain management (GSCM) are both multidimensional constructs, this paper empirically investigates the impact of different dimensions of SCI on different practices of GSCM and the contribution of different practices of GSCM to business performance. The aim is to uncover the distinctive role of each dimension in achieving environmental sustainability along the supply chain. A conceptual model is proposed to link supplier and customer integration to both internal GSCM within the company and external GSCM with the suppliers as well as business performance. The study is based on a survey of Chinese manufacturing companies. The results show that integration with suppliers only supports external GSCM while integration with the customer supports both internal and external GSCM. It also finds that external GSCM has no positive relationship with business performance but supports internal GSCM, which positively influences companies’ business performance. The results suggest that considering construct multidimensionality brings the opportunity of closely scrutinizing the relationships between SCI, GSCM, and business performance. Different dimensions have different effects in achieving environmental sustainability by integrating different partners along the supply chain. The separation of internal and external GSCM and the exploration of the result of the multidimensionality of the proposed constructs may be contributions to this field. The implications of supporting a green supply chain are explored.

1. Introduction

The attainment of environmental sustainability is relevant to the coordination and collaboration between partners of the entire supply chain [1]. Supply chain activities such as design, purchasing, production, transportation, and packaging are all related to sustainability. Green supply chain management (GSCM) has accordingly gained increasing popularity recent years as it aims to integrate environmental sustainability into the management of the supply chain, including the internal issues within a company and external relationships across partners [2]. To this end, deep and close partnerships between supply chain stakeholders are essential [3,4]. Managing environmental sustainability beyond corporate boundaries and integration with different stakeholders, such as suppliers and customers, are the core concepts of green supply chain research.

The core concept of GSCM raises the importance of supply chain integration (SCI) in achieving environmental sustainability. At the core of the SCI concept is the strategic coordination and collaboration of a company with its suppliers and customers to streamline core business process to fulfill customers’ and other stakeholders’ needs [5]. Over the previous two decades, SCI has been a hot subject of research in operations and supply chain fields [6,7] and has been proven to have positive and significant impacts on business performance [8,9]. SCI is also gaining growing significance in the fields of sustainable/green supply chains to coordinate and aid in the collaboration of suppliers and customers in achieving environmental sustainability. Recently coined terms such as green supply chain integration [10] and sustainable supply chain management integration [11] explicitly demonstrate the growing awareness of the significance of integration along the supply chain to achieve environmental sustainability.

However, little effort has been made in empirically testing the influence of SCI on the adoption of GSCM practices or its potential impact on business performance. SCI and GSCM are both multidimensional constructs [12]. SCI typically involves upstream integration with suppliers and downstream integration with customers [13], and GSCM involves external green supply chain management practices with suppliers and internal green supply chain management practices within the boundary of a focal company [14]. Multidimensionality may cause relationship complexity [15]. Each dimension has its distinctive role due to the involvement of different functions and stakeholders, or the requirement of investment in various resources and capabilities. For example, Zhu et al. (2012) [16] examined the sequential relationship between internal GSCM and external GSCM and found that internal GSCM mediated the impacts of external GSCM on performance in most occasions. Flynn et al., (2010) [17] found that different dimensions of SCI have different effects on firm performance as they involve different supply chain partners. Golicic and Smith (2013) [18] found that working closely with the supplier on environmental sustainability would have a more significant impact on firm performance than working with the customer. Therefore, the manner by which different dimensions of SCI affect those of internal and external GSCM is an important question for scrutiny. These relationships may differ depending on the specifics of both SCI and GSCM. Exploring such nuanced relationships can bring sophisticated insights into the management of supply chain activities.

Besides this, the specific economic consequence of GSCM remains ambiguous, although many pieces of evidence support a positive contribution [19,20,21]. Implementing initiatives of GSCM may incur economic costs, resulting in a negative effect on business performance. However, a green supply chain is only sustainable when it is economically viable and financially justified. There has been a misgiving about the potentially negative relationship between sustainability and business performance [11]. As internal and external GSCM practices involve different functions and partners, they may have a specific impact on business performance. The consideration of the multidimensionality of GSCM thus offers a more nuanced investigation into how different dimensions of GSCM relate to business performance and hence provides a novel way to explore the contribution of GSCM to business performance.

The above issues are particularly pressing for Chinese manufacturing firms. The rapid economic growth in China over the past 40 years has caused serious sustainability challenges for the country [22]. Government agencies are enforcing rigorous regulations in an attempt to mitigate the undesirable effects of industrial activities on the natural environment [23]. Community and market stakeholders are putting increasing pressure on companies to implement environmental initiatives [24,25]. This trend forces companies to find ways to balance economic benefits with environmental performance [22,26]. There are important issues which are still to be addressed by Chinese manufacturing firms regarding how they can be more proactively involved in sustainability development; i.e., whether costly sustainability activities are only carried out to meet regulatory requirements but at the expense of business performance, and how businesses can collaborate with different stakeholders to achieve their green objectives. Chinese manufacturing firms are ideal subjects to examine these urgent questions.

This study focuses on the impact of different dimensions of SCI on the adoption of GSCM practices and the impact of different dimensions of GSCM on business performance. The aims are (1) to explore the effect of both supplier integration and customer integration on external GSCM beyond a company and internal GSCM within a company, and (2) to examine the impact of GSCM on business performance. We attempt to determine how companies might use supply chain integration to achieve environmental sustainability along the supply chain and eventually improve their business performance. Considering the multidimensionality of both SCI and GSCM constructs and the still mixed relationship between GSCM and business performance, this study offers a nuanced insight of the effects of different dimensions to uncover the role of different partners (i.e., supplier and customer) and different relationships (i.e., internal and external) in achieving a green supply chain. These are the contributions of this study.

The paper is structured as follows: After the introduction, a brief review of SCI and GSCM literature presents the nature of multidimensionality and its effect on construct relationships. Hypotheses are then proposed to elaborate on the relationships between SCI, GSCM, and business performance. Survey data from Chinese manufacturing companies are analyzed using partial least square structural equation modeling, and Section 4 presents the results. Theoretical and practical implications are then discussed. The paper ends with a discussion about limitations and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Supply Chain Integration (SCI)

Flynn et al., (2010) [17] define SCI as the degree to which a manufacturer strategically collaborates with its supply chain partners to achieve effective and efficient flows of products and services, information, money, and decisions. Flynn et al., (2010) [17] also elucidate three important SCI characteristics that are relevant to GSCM. First, SCI entails both strategic collaboration and operational coordination between partners. SCI highlights the importance of mutual trust, long contracts, efficient conflict resolution, and information sharing between the partners [27]. These collaborative and coordinative characteristics are essential for achieving environmental sustainability along the whole supply chain [4,28], as a green supply chain involves operational and strategic ongoing partnerships between different parties [20]. Second, SCI emphasizes the streamlining of intra- and inter-organizational processes. SCI can encompass both internal and external practices of green supply chain management during partner coordination and collaboration [10]. Third, the purpose of SCI is to maximize customer value. Providing environmentally friendly offerings to customers is thus one of its objectives, as customers are exerting increasing pressure upon the supply chain to do so. Therefore, SCI, at its core, facilitates the implementation of GSCM.

It is important to identify different dimensions of SCI. Although some authors (e.g., [29]) propose a unidimensional perspective of SCI, SCI is usually treated as a multi-dimensional construct. Several classifications exist to suggest dimensions of SCI, such as forms of integration (i.e., delivery vs. information integration), directions of integration (i.e., upstream vs. downstream integration), and the extent of integration [13]. In general, supply chain partners refer to the suppliers and customers of a company. Upstream integration with suppliers and downstream integration with customers are therefore essential and are two widely accepted dimensions of SCI [7,30]. Research related to supplier integration is common in the fields of logistics, purchasing, and product development studies [31]. However, the stakeholder theory suggests that the awareness of customers’ desire for more environmentally friendly products and services is a compelling incentive for the green supply chain [32]. Future research should, therefore, consider the influence of both customers and supplier integration on the green supply chain.

Strengthening the distinct dimension of SCI would have a distinctive impact on the efficiency and effectiveness of supply chain management. This proposition is specifically addressed by the contingent view of the significance of SCI. For example, Frohlich and Westbrook (2001) [13] empirically demonstrate that different directions of integration (i.e., toward suppliers or customers) and the degree of integration have different effects on performance. Vachon and Klassen (2006) [33] find that logistic integration with suppliers enhances environmental monitoring, while customer integration does not have such an effect. Flynn et al., (2010) [17] found that the strength of customer integration would significantly affect firm performance. Therefore, examining the distinctive role of different SCI dimensions can bring useful insights into the improvement of firm performance by integrating with supply chain partners. However, most previous studies focus on operational and business areas, marketing, and innovation performance [34,35]. The effect of SCI on sustainability (e.g., GSCM) requires further study.

2.2. Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM)

GSCM is a set of practices that aim to integrate environmental concerns into the inter- and intra-organizational process of the supply chain [36]. GSCM refers not only to the internal issues of a company but also relates to external suppliers and customers. In this vein, practices of GSCM broadly include internal practices that can be deployed independently within the boundary of focal company and external practices that entail some extent of collaboration and coordination across boundaries of supply chain partners [33]. Typical internal GSCM practices include waste reduction, material conservation, and internal communication and education of environmental issues, while typical external GSCM practices include green purchasing, green supply, eco-design or reverse logistics [37].

The cross influence between different GSCM practices, especially between internal and external GSCM, has received a great deal of attention. Due to multidimensionality, the conclusion about this relationship is far from established. Some authors argue that internal commitment and capabilities development is the antecedent of external green practices [38]. When a focal company has a high-level adoption of green practices internally, and it would include high-level commitment and capabilities which are developed to cooperate with suppliers and other partners to engage in across-organizational green practices [39]. Thus, external GSCM is the extension of internal GSCM, and the adoption of internal GSCM practices would positively affect the application of external GSCM practices. For example, Zhu et al., (2012) [16] argue that internal GSCM and external GSCM should be adopted in a specific sequence to effectively achieve performance benefits. They propose that internal GSCM mediates the effect of external GSCM on economic performance. However, this proposition lacks substantial theoretical underpinning and is largely a data-driven conclusion. In another study, Zhu et al., (2013) [14] propose that external GSCM mediates the effect of internal GSCM on economic performance. Mitra and Datta (2013) [40] reviewed a large number of studies and concluded that there is no consensus with respect to the causality and the direction of causality between internal and external GSCM in the existing literature. They also propose that external GSCM positively affects the application of internal GSCM. Therefore, the effect of the cross-influence between dimensions of GSCM is not conclusive and needs further investigation.

Another core topic of GSCM study is to ascertain the contribution to business performance. Multidimensionality also matters. Miroshnychenko et al., (2017) [41] find that different dimensions of GSCM have different effects on financial performance. While pollution prevention (an internal GSCM) is the primary driver of financial performance, green product development (an external GSCM) only plays a secondary role, and the adoption of ISO 14001 even negatively affects financial performance. Khaksar et al., (2016) [42] find that green suppliers have a negative effect on a firm’s competitive advantage, while green innovation has a positive effect on both competitive advantage and environmental performance.

Although multidimensionality is critical to exploring the efficiency and effectiveness of GSCM, its importance is far from fully recognized. Some treat GSCM as one construct without considering the importance of separated internal and external GSCM practices [43,44], while others do not explore the relationship between different dimensions of GSCM. although the nature of multidimensionality is noticed [45]. Although there are a few studies that separate internal and external GSCM, their conceptual models are very different. For example, Wong et al., (2011) [46] conducted research which contains both internal and external GSCM. The internal GSCM covers product and process stewardship while external GSCM refers to the environmental management capability of suppliers. The study investigates the relationship between internal environmental issue and performance. However, external GSCM was a moderating factor. Its relationship with internal GSCM and performance was not investigated. On the contrary, Rao and Holt’s (2005) [45] internal GSCM refers to green production, and external GSCM covers both inbound green practices from suppliers and outbound green practices to the customers and stakeholders. They tested the contribution of external GSCM to performance, whereas the effect of internal GSCM on performance was not tested but was regarded as a factor that positively influences external GSCM, which contributes to business performance. Chan et al., (2012) [47] include both internal and external GSCM, but they only test the relationship between green purchases and business performance. Therefore, the relationship between internal and external GSCM and its impact on business performance needs further investigation. This paper aims to empirically investigate the impact of supply chain integration on both internal and external GSCM and business performance in Chinese manufacturing companies.

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. The Impact of SCI on GSCM

The literature implies that there is a positive relationship between supply chain integration and environmental cooperation between partners and that the collaborative behavior of businesses, suppliers, and customers is an essential component of the green supply chain [48].

Complexity, problems of coordination, and insufficient communication are frequently identified as obstacles when implementing a green supply chain [28]. Cooperation between supply chain partners can help control the associated costs [49]. Strong supply chain integration implies a good understanding of the capabilities and goals of partner organizations in achieving environmental sustainability. This increases the possibilities of collective solutions, which can reduce undesirable environmental impacts, such as the processing and transportation of materials [50].

The pressure to achieve environmental sustainability usually comes from external stakeholders transferring this from end customers to the company, then to suppliers. Ongoing information exchange and trust-building between the focal company, its upstream suppliers, and its downstream customers are required. This level of integration along the supply chain can effectively support internal and external GSCM.

For successful external GSCM, suppliers must transform their production processes to become more environmentally friendly, train their personnel, redesign their products to meet the environmental standards required by the focal company, and implement a completely sustainable strategy. This transformation requires broad cooperation with the focal company and trust between the two sides. Long-term integration may assist this. Pagell and Wu (2009) [51] suggest that businesses need to educate their suppliers and persuade their suppliers to educate each other. The integration of upstream suppliers improves the environmental sustainability of a manufacturing company.

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Supplier integration (SI) has a positive impact on the adoption of external GSCM.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Supplier integration (SI) has a positive impact on the adoption of internal GSCM.

The impacts of internal sustainability and supplier integration are the subjects of comprehensive research in the GSCM field, while the effect of customers has not been fully explored [52]. However, consumer pressure is a significant incentive in implementing practices of GSCM [53], and the regard of customers for environmental conservation is a crucial incentive for transformation. Customers can require their suppliers to consider environmental issues when offering products and materials. Suppliers must, therefore, work closely with customers to understand their requirements early in the product development stage so that they can select the appropriate materials and packaging. Closer integration with customers can facilitate information sharing, which helps the focal company to better understand the environmental requirements of its customers and implement internal practices to meet customer requirements. It can also help the focal company to extend environmental practices to its suppliers when inbound materials would affect the environmental performance of the end product [10]. Therefore, customer integration will improve the adoption of both the internal and external GSCM of a manufacturing company.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Customer integration (CI) has a positive impact on the adoption of external GSCM.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Customer integration (CI) has a positive impact on the adoption of internal GSCM.

3.2. The Impact of External GSCM on Internal GSCM

Although there is no consensus about the relationship between internal and external GSCM, we propose that the adoption of external GSCM facilitates the adoption of internal GSCM. Although internal commitment and capability is essential in developing external practices, we argue this proposition is only effective in the short term or at its start. In the long run, the inputs from external partners’ (i.e., suppliers’) services are the prerequisites of internal green practices and outcomes. Suppliers provide raw materials and components, which influence the environmental standards and operations of the company; that is, a company is no greener than its supply chain [54]. Specifically, as the contribution of GSCM to financial performance is one of our research questions, we assume that external GSCM facilitates the adoption of internal GSCM, which will then contribute to financial performance. Hollos et al., (2012) [55] propose that supplier cooperation enhance internal green practices. Mitra and Datta (2013) [40] assume that green purchasing practices positively relate to green manufacturing practices, and empirical evidence supports this. Rao (2002) [43] tests the positive effect of green suppliers on internal sustainability. Seuing and Gold (2013) [4] argue that suppliers are a crucial consideration when businesses move toward sustainability. Therefore, the sustainability of suppliers’ operations will directly affect the environmental considerations of the focal company. The following hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

External GSCM has a positive impact on the adoption of internal GSCM.

3.3. The Impact of GSCM on Business Performance

The impact of GSCM practices on business performance has been debated for many years. Green supply chain activities are often initiated by environmental regulation rather than by performance improvements. Compliance with environmental regulations compels firms to act regarding the environmental effects of their activities [56]. Theoretical analyses argue that there is no given automatic economic (positive or negative) effect of GSCM on competitiveness and economic performance [57,58]. However, the supply chain is not sustainable if it cannot produce a positive economic result, and to be genuinely green, it must achieve its operational objectives within a realistic financial structure and provide environmental benefits [59]. A nature resource-based view (NRBV) might be the widely accepted theory that explains how green activities can bring competitive advantages [60]. NRBV argues that the natural environment has increased the severity of constraints on business, and environmental sustainability fits well with the profit motive of business because the competitiveness of business is rooted in the capabilities to conduct business activities that are green [61]. Internal GSCM can not only reduce the environmental damage of business activities but also provides innovative products or processes to protect the natural environment. Therefore, internal GSCM can produce a number of resources that together improve the competitiveness of a focal company by offering a more innovative or low-cost product. Similar to internal GSCM, external GSCM can also bring about competitive advantages by providing valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources and capabilities [62]. Besides this, relational rent, which derives from cross-boundary resources and capabilities between partners, is another source of competitive advantage [63]. Recent empirical evidence identifies a positive relationship between GSCM practices and performance [64,65,66]. Wong et al., (2015) [67] suggest that manufacturers can reap financial and environmental benefits through GSCM. Therefore, the green supply chain leads to competitiveness and improved business performance. We propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4a (H4a).

External GSCM has a positive impact on business performance (BP).

Hypothesis 4b (H4b).

Internal GSCM has a positive impact on business performance (BP).

However, as we propose that external GSCM has a positive effect on internal GSCM, we assume that the effect of external GSCM on business performance is mediated by internal GSCM. This is obvious considering the value-added sequence of supply chain activities. External GSCM serves as the inbound function of internal GSCM, which then contributes to business performance. From a supply chain standpoint, the effect of external GSCM is only valid after all the inbound activities and materials go through the internal process of a focal company. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4c (H4c).

External GSCM does not have a direct effect on business performance. Internal GSCM mediates the effect of external GSCM on business performance.

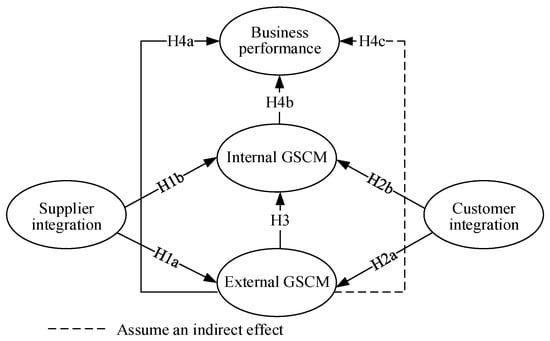

The hypotheses can be summarized in a conceptual model, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model and hypotheses. GSCM: green supply chain management.

4. Methodology

4.1. Measurement

The measurement instrument is mostly based on two sets of literature. The first set is about supply chain integration, and the second set is about the green supply chain. The measurement instrument is listed in the Appendix A.

Following Frohlich and Westbrook (2001) [13], supply chain integration was operationalized based upon eight different kinds of activities that manufacturers commonly employ to integrate their operations with suppliers and customers, such as sharing inventory and production information, order tracking, dedicated capacity, and vendor management inventory. These activities happen with both the supplier and customer in order to investigate their distinctive effect on GSCM. Thus, they are used to measure supplier integration and customer integration. Frohlich and Westbrook (2001) [13] tested the reliability and validity of the measurement.

The measurement of external GSCM and internal GSCM followed the instrument of Zhu et al., (2012) [16] used to include different practices of GSCM. External GSCM was operationalized as environmental practices with suppliers and was measured including three kinds of practices, such as monitoring a supplier’s environmental performance or collaborating with a supplier to improve environmental performance. Internal GSCM was operationalized as environmental practices conducted within the focal company, and the measurement of internal GSCM included four kinds of practices: improving the environmental performance of the product and process, improving the environmental impacts of products by appropriate design measures, monitoring the environmental performance improvement, and using a business strategy with environmentally sound products and processes.

Business performance measurement includes sales, return on sales, return on investment, and market share by asking the respondents to indicate the extent of performance variation compared with three years ago. The measurement includes both financial and nonfinancial performance indicators and is sufficient to measure business performance by including growth, profitability, and market share dimensions [68].

4.2. Sample and Data Collection

The data collection was conducted in Eastern China, the most developed region in China, which faces severe environmental challenges. The target respondents were the director of operations and supply chain management or an equivalent position to ensure their professionalism regarding GSCM activities. The respondents were asked to rate their firm’s level of implementation of SCI and GSCM during the last three years and the change of business performance compared with three years ago on a 5-point Likert scale, in which 1 represents a “low level of implementation or performance decreases,” and 5 represents a “high level of implementation or performance increases.” Under the support of China Association of Management, a national organization devoted to management research and diffusion which helped to provide a list of Eastern Chinese manufacturing firms, 500 companies were contacted to participate in the study, and 220 companies agreed. The questionnaire was sent by mail or email. A total of 184 samples were received, but after carefully checking for missing data, 22 cases were excluded in the late study, resulting in a valid sample size of 162 and a valid response rate of 73.6%. These excluded cases were treated as non-response samples. To examine the non-response bias, we conducted a t-test, and the results showed that there was no significant difference between these missing data cases and other cases in term of company size (number of employees: t = −0.658, and sales: t = 1.453). Therefore, the non-response bias was not a severe problem of the study.

4.3. Common Method Bias

The data collection method took some steps to reduce the problem of common method bias: (1) The questionnaire was completed by operations/supply chain directors or equivalent positions, and (2) the confidentiality of the respondents’ information was guaranteed and protected. However, as the data were collected in the same session and from single sources, the problem of common method bias had to be scrutinized. To this end, a Harman’s single-factor test was conducted following the traditional procedure of loading all items into an exploratory factor analysis [69]. The total variance explained by factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 was 65.96%, while the largest eigenvalue factor accounted for 12.27% of variance. Therefore, no single factor accounted for the majority of the covariance among the measures. The common method bias is not a severe problem of the current research.

5. Analysis and Results

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used by applying the SmartPls package. This analysis technique is applied because of the following methodology advantages [70]: (1) Minimum requirements of sample size and residual distribution to have enough statistical power and robustness; (2) tolerance of non-normal data; and (3) maximization of the variance of the dependent variables explained by the independent ones instead of reproducing the empirical covariance matrix. Considering the relatively small size of 162 valid samples, the possibility of the non-normal distribution of a 5-point Likert scale, and the aim of explaining the effects of SCI on GSCM and business performance, PLS-SEM is an appropriate data analysis approach. The minimum sample size for robust PLS-SEM is ten times the maximum number of paths leading to endogenous constructs [71]. This rule leads to a minimum sample size of 30 for this study. Therefore, our sample size of 162 was adequate for the analysis. The following analysis and results evaluation procedure follow the procedure recommended by Hair (2013) [70].

5.1. Measurement Model Results

The reliability evaluates the consistency of the measurement. First, we evaluate the internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR). Cronbach’s alpha is universally used but has the limitation of assuming that all indicators are equally reliable and generally underestimating the internal reliability [70]. Therefore, CR is recommended as a supplementary and preferable evaluation in PLS-SEM. The α and CR values (Table 1) are all above the recommended level of 0.7, except for the α value of external GSCM, which is close to 0.7, so we accept that the internal consistency of the measurement is substantial. Then, we use standardized loading to evaluate the indicator reliability to assess convergent validity. The values of all loadings are greater than 0.7, except for six indicators which are all above 0.6 and greater than the normally accepted value of 0.5 [72]. We then examine the values of average variance extracted (AVE), which are all greater than 0.5. Therefore, the measurement has substantial convergent validity. The discriminant validity is evaluated by examining the value of cross loading and the Fornell–Larcker criterion. First, the loading of each indicator on its associated construct is greater than all its loadings on other constructs (Table 2). Second, each construct’s square root value of AVE is greater than all the correlations of this construct with other constructs, indicating that each construct shares more variance with its associated indicators than with any other constructs. Therefore, the measurement model shows adequate discriminant validity.

Table 1.

Reliability and validity evaluation. CR—composite reliability, AVE—average variance extracted.

Table 2.

Partial least square (PLS) loadings and cross-loadings of indicators.

5.2. Structural Model Results

First, the collinearity of the structural model was examined. The maximum value of the variance inflation factor (VIF) is 2.138, and other VIF values are below 2.0—all are below the threshold of 5.0, indicating that the collinearity between the exogenous variables is not a severe problem.

Then, we examine the path coefficients (Table 3). Supplier integration has a positive effect on external GSCM (coefficient = 0.372; t = 3.665). However, supplier integration has no significant effect on internal GSCM (coefficient = 0.123; t = 1.378). Customer integration has a positive effect on external GSCM (coefficient = 0.208; t = 2.146) and internal GSCM (coefficient = 0.195; t = 2.069). External GSCM has a positive effect on internal GSCM (coefficient = 0.477; t = 0.7446). External GSCM has no significant effect on business performance (coefficient = 0.014; t = 0.112), while internal GSCM has a positive effect on business performance (coefficient = 0.235; t = 2.145).

Table 3.

Path coefficients, significance, and hypotheses test results.

The determination coefficient R2 value is a measure of the model’s predictive accuracy. It indicates the variance of the endogenous variable explained by its predictors in the structural model. As shown in Table 4, the model explains 46.3% of the variance of the internal GSCM and 29% of the variance of the external GSCM. However, the predictors only explain 6% of the variance of business performance. R2 values of 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75, respectively, represent weak, moderate and substantial values [70]. Therefore, internal GSCM and external GSCM are well predicted by their predictors, while the model only predicts a very small variance percentage of business performance. This is understandable, as many factors would affect business performance. However, our model shows that GSCM has a significant influence on business performance, although with little effect. The value of the f2 effect size is also examined. The f2 effect size measures the impact of a specified exogenous variable on an endogenous variable. The values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, respectively, represent small, medium and large effects. Therefore, external GSCM has a large impact on internal GSCM. Customer integration has a small-to-medium impact on both external and internal GSCM. Supplier integration only has a small impact on external GSCM, while the impact of external GSCM on business performance and of supplier integration on internal GSCM is very small.

Table 4.

R2 and f2 effect size.

5.3. Testing the Mediating Effect of Internal GSCM

We assume that internal GSCM mediates the effect of external GSCM on business performance. To test this meditating effect, we apply the bootstrap method, setting the resampling size to n = 1000. Bootstrapping is a popular method to test indirect effects and has a methodological advantage over the traditional Sobel test [73].

The result is shown in Table 5. The direct effect of external GSCM on business performance is 0.014 (t = 0.112) and is not significant at the p < 0.05 level. The indirect effect of external GSCM on business performance via internal GSCM is significant at the p < 0.05 level (0.112, t = 1.995). Examining the 97.5% confidence interval for the indirect effect, the low-level value is 0.004, which is above zero. The data analysis result supports the conclusion that external GSCM does not have a direct effect on business performance. The effect of external GSCM on business performance is mediated by internal GSCM. This result supports the argument that different dimensions of GSCM have distinctive roles in the supply chain.

Table 5.

Test of the mediating effect of internal GSCM on the relationship between external GSCM and business performance.

6. Discussions and Implications

This paper empirically tests the impact of supply chain integration on internal and external GSCM practices and business performance in Chinese manufacturing companies. The results show that integration with suppliers only supports external GSCM, while integration with the customer supports both internal and external GSCM. It is also found that external GSCM has no direct relationship with business performance, but it supports internal GSCM, which positively influences a company’s business performance. This study pays a great deal of attention to the multidimensionality of both SCI and GSCM and explores the distinctive role of each dimension, which may be a new contribution to the GSCM field with further implications and trigger new future research.

6.1. The Impact of SCI on GSCM

The results show that integration with upstream and downstream partners would have different roles in applying GSCM. Supplier integration positively affects the implementation of external GSCM practices between a company and its suppliers, while customer integration positively affects both internal GSCM practices within the boundary of the focal company and external GSCM practices across the interface of the focal company and its supplier.

This result shows that customer integration is essential and has a distinctive role in GSCM practices. Although the initiation of environmental sustainability commonly starts with governmental regulations on environment protection, environmental issues are ultimately evaluated by customers who use the products. Government regulations usually address only pollution issues, whereas customers are concerned with safety, cost, and reputation from an environmental perspective. The customer is therefore essential in improving levels of sustainability and in upholding environmental sustainability standards. Through intensive customer integration, manufacturing companies gain more awareness of the environmental issues of their customers and will consequently implement environmental programs in internal operations processes to meet customers’ requirements, such as product or process stewardship. Besides this, as the value to the customer is supplied via a supply chain, the requirement from customers will then transfer upstream to its suppliers to implement collaborative green practices [74]. Therefore, as our results showed, customer integration has positive effects on both internal and external GSCM. Customers may therefore be the critical force steering manufacturing companies toward environmental sustainability. Previous studies of GSCM have focused primarily on the role of the upstream supplier [75,76]. The impact of downstream customer engagement on sustainability initiatives is a potential area for further investigation.

The result also implies that integration with suppliers leads to collaborative green practices between a focal company and its upstream partners. However, supplier integration does not affect the practices of internal GSCM. This means that suppliers may not be involved when a focal company starts to implement internal GSCM. This result is consistent with previous conclusions that internal GSCM starts as an internal strategic imperative and top-management commitment [77]. Internal GSCM is then extended to the interface with suppliers. Then, integration with a supplier is essential to implement external GSCM.

Comparing the different effect of supplier and customer integration, we find that the multidimensionality of SCI matters in affecting the adoption of GSCM. The customer is the driving force in adopting GSCM, as some authors argue that customer pressure is the primary driver to stimulate firms to engage in sustainability [78]. This driving force can also translate into external practices with suppliers. Integration with customers therefore facilitates information sharing and trust-building that stimulates the focal company to implement internally oriented green practices. Supplier integration, however, is important when adopting external GSCM.

6.2. The Impact of GSCM on Business Performance

The relationship between GSCM and business performance has been tested empirically, and internal GSCM has a positive and significant impact on business performance. This gives hints to the manufacturing companies that environmental sustainability should not only be implemented for environmental protection but also helps companies to improve their business performance, such as their market share and return on sales. Hence, the business performance and competitiveness of manufacturing companies could be enhanced. This supports the argument that “greener is cheaper”.

Sustainable initiatives are often seen as social responsibility initiatives that do not necessarily lead to financial rewards [1], and thus the evidence that “greener is cheaper” may provide managers with a clear framework to incorporate business performance into sustainable management. At the core of sustainability is the intersection of environmental, economic, and social performance [79], which explicitly illustrates that engagement in GSCM need not be simply a reactive action designed to meet regulations, but should be proactively planned as a strategic action to gain sustainable competitive advantages.

External GSCM does not directly contribute to business performance but enhances internal GSCM. Its effect on business performance is fully mediated by internal GSCM. Therefore, working with suppliers to achieve firm-level sustainability is necessary but not sufficient in improving business performance. Supply-side sustainability should be absorbed by internal operations and contribute to demand-side value creation. The mediating effect of internal GSCM on the external supplier relationship is an often-mentioned and explored topic [16]. Nevertheless, the direct impact of supply-side sustainability on business performance is assumed by neglecting the mediating effect [2,6]. Our findings supplement previous wisdom, offering a more profound understanding of the role of supply-side activities. More research is therefore needed to more rigorously explore the relationship between supply-side sustainability, internal operations and business performance.

6.3. Managerial Implications

The results also present several useful management suggestions for firms and managers in advancing towards a green supply chain. First, the results suggest managers should build a substantial relationship with customers in green advancement. Firms are usually reactive to customer’s green requirements; however, as the role of the customer is recognized by this study and others (e.g., [74]), an active or even proactive strategy to integrate customers will help firms in their green journey. The integration with customers can start with information sharing with respect to products, production, and logistics. Firms should then collaborate with customers in product and process design to incorporate green objectives into supply chain management. Second, our results remind managers to pay a good deal of attention to the distinctive role of different partners in achieving a green supply chain. The supplier can offer supply-side advantages, while a customer’s influence can move upstream to contribute to the whole supply chain. Therefore, managers should be aware of the different improvement opportunities provided by different partners and tactically manage these relationships for effective performance improvement. Third, firms should invest first in internal operations to achieve green objectives. Internal GSCM provides the basis of the green supply chain in that firms will have the capability to absorb upstream green outcomes from suppliers. Without a substantial internal capability, firms will find it difficult to transfer benefits from external collaboration to contribute to the green supply chain. Fourth and finally, we suggest a proactive strategy in the green supply chain since the contribution of the GSCM to business performance is supported by the results. A proactive strategy means rethinking the product and process compared with the requirements of sustainable development and redesigning the product and process (or even business model) strategically to capitalize on green-related opportunities.

7. Limitations and Future Research

Our paper also has some limitations which may offer new opportunities for future research. First, the conceptualizations of sustainability cover three dimensions: Economic, social and environmental. Like most existing GSCM studies, this paper focuses only on the environmental dimension. Future research can be extended to the other two dimensions or all three dimensions.

Second, the previous results were controversial regarding the impact of GSCM on business performance. This paper reveals that internal GSCM has a positive relationship with business performance while external GSCM has no direct effect on business performance. There is literature reporting a nonlinear and/or conditional relationship or a bi-directional relationship between environmental sustainability and business performance (e.g., [80]). Therefore, the relationship between GSCM and business performance might be complex and based on contingent factors. This should be investigated further with more advanced methods such as non-linear correlation.

Third, in the past ten years, supply chain management has been studied from several perspectives, such as the manufacturing process, new product development, quality management, and technology transfer. Environmental sustainability will be a new trend in supply chain management research and will be enhanced in the future. The external GSCM may even be separated from supplier and customer perspectives and may provide insight into upstream and downstream environmental issues. Multidimensionality in supply chain management and specifically GSCM should be further explored. Recently, some authors have started to examine the role of customers [74,78,81]. More studies are needed to explore the different roles of suppliers and customers in GSCM.

Finally, this paper is based on data from Chinese manufacturing companies, and the results may not be able to be extended to other countries. For example, it is found that supplier integration only influences the external GSCM but has no direct impact on internal GSCM; is this because Chinese companies do not involve suppliers in internal environmental issues yet, or is it a generic pattern for all companies? Considering that Chinese companies are only beginning to implement GSCM [82], this result may only apply to the start-up stage when companies start their internal commitment to green practices. A comparison between developed and developing countries or emerging economies may provide more nuanced insights, especially for joint ventures and global companies which produce in one country, purchase raw materials in another and sell products in others.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to the conceptualization and writing of this article. Data analysis was conducted by W.N.

Funding

This research was funded by Provincial Social Science Foundation of Zhejiang, China, grant number 16NDJC147YB, and National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 16BGL082.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement Instrument.

Table A1.

Measurement Instrument.

| Internal green supply chain management (Zhu et al., 2012) |

| A business strategy with environmentally sound products and processes |

| Improving the environmental impact of products by appropriate design measures, e.g., design to recycle |

| Improving the environmental performance of processes and products (e.g., environmental management system, Life-Cycle Analysis, Design for Environment, environmental certification) |

| Overall monitoring of environmental performance improvement |

| External green supply chain management (Zhu et al., 2012) |

| Collaborating with suppliers to improve the environmental performance |

| Monitoring and auditing suppliers’ environmental performance using established guidelines and procedures |

| Improving the environmental impact generated by transportation of materials/products and outsourcing of process steps |

| Supplier integration (Frohlich and Westbrook, 2001) (The implementation of the following activities with suppliers) |

| Share inventory level information |

| Share production planning and demand forecast information |

| Order tracking |

| Agreements on delivery frequency |

| Dedicated capacity |

| Vendor management inventory or consignment stock |

| Plan, forecast and replenish collaboratively |

| Just-in-time replenishment |

| Customer integration (Frohlich and Westbrook, 2001) (The implementation of the following activities with customers) |

| Share inventory level information |

| Share production planning and demand forecast information |

| Order tracking |

| Agreements on delivery frequency |

| Dedicated capacity |

| Vendor management inventory or consignment stock |

| Plan, forecast and replenish collaboratively |

| Just-in-time replenishment |

| Business performance (Venkatraman and Ramanujam, 1986) |

| Market share |

| Return on sales |

| Sales |

| Return on investment |

References

- Carter, C.R.; Easton, P.L. Sustainable supply chain management: Evolution and future directions. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2011, 41, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Chavez, R.; Feng, M.; Wiengarten, F. Integrated green supply chain management and operational performance. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2014, 19, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, A.; Leat, M.; Hudson-Smith, M. Making connections: A review of supply chain management and sustainability literature. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Gold, S. Sustainability management beyond corporate boundaries: From stakeholders to performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Ellinger, A.E.; Kim, K.K.; Franke, G.R. Supply chain integration and firm financial performance: A meta-analysis of positional advantage mediation and moderating factors. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuschner, R.; Rogers, D.S.; Charvet, F.F. A meta-analysis of supply chain integration and firm performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2013, 2, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, S.E.; Magnan, G.M. The rhetoric and reality of supply chain integration. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2002, 32, 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golini, R.; Caniato, F.; Kalchschmidt, M. Supply chain integration within global manufacturing networks: A contingency flow-based view. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2017, 28, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiengarten, F.; Longoni, A. A nuanced view on supply chain integration: A coordinative and collaborative approach to operational and sustainability performance improvement. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. The influence of green supply chain integration and environmental uncertainty on green innovation in Taiwan’s IT industry. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2013, 18, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J. Sustainable supply chain management integration: A qualitative analysis of the german manufacturing industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumpp, C.; Endrikat, J.; Zopf, C.; Guenther, E. Definition, conceptualization, and measurement of corporate environmental performance: A critical examination of a multidimensional construct. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 2, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, M.T.; Westbrook, R. Arcs of integration: An international study of supply chain strategies. J. Oper. Manag. 2001, 19, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K. Institutional-based antecedents and performance outcomes of internal and external green supply chain management practices. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2013, 19, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrikat, J.; Guenther, E.; Hoppe, H. Making sense of conflicting empirical findings: A meta-analytic review of the relationship between corporate environmental and financial performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K. Examining the effects of green supply chain management practices and their mediations on performance improvements. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 1377–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, B.B.; Huo, B.; Zhao, X. The impact of supply chain integration on performance: A contingency and configuration approach. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golicic, S.L.; Smith, C.D. A meta-analysis of environmentally sustainable supply chain management practices and firm performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2013, 49, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Sun, H. The effect of sustainable supply chain management on business performance: Implications for integrating the entire supply chain in the Chinese manufacturing sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 1176–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, M.; Knemeyer, A.M. Exploring the integration of sustainability and supply chain management: Current state and opportunities for future inquiry. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013, 43, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Omair, M.; Choi, S. A multi-objective optimization of energy, economic, and carbon emission in a production model under sustainable supply chain management. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K. Green supply chain management: Pressures, practices and performance within the Chinese automobile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhang, L. China’s environmental governance of rapid industrialization. Environ. Politics 2006, 15, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Bi, J.; Yuan, Z.; Ge, J.; Liu, B.; Bu, M. Why do firms engage in environmental management? An empirical study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1036–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guoyou, Q.; Saixing, Z.; Chiming, T.; Haitao, Y.; Hailiang, Z. Stakeholders’ influences on corporate green innovation strategy: A case study of manufacturing firms in china. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, X. Corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance in China: An empirical research from Chinese firms. Corp. Gov. 2011, 11, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.W.Y.; Sancha, C.; Gimenez, C. A national culture perspective in the efficacy of supply chain integration practices. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 193, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, E.D.; Roth, A.V.; Dean, J.W., Jr. The influence of an integration strategy on competitive capabilities and business performance: An exploratory study of consumer products manufacturers. J. Oper. Manag. 2003, 4, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiengarten, F.; Humphreys, P.; Gimenez, C.; Mcivor, R. Risk, risk management practices, and the success of supply chain integration. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 171, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Ni, W. The impact of upstream supply and downstream demand integration on quality management and quality performance. Int. J. Quality Reliab. Manag. 2012, 8, 872–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, B.S. A hard nut to crack! Implementing supply chain sustainability in an emerging economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 96, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Extending green practices across the supply chain: The impact of upstream and downstream integration. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2006, 26, 795–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ke, W.; Wei, K.K.; Hua, Z. Effects of supply chain integration and market orientation on firm performance: Evidence from China. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013, 33, 322–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.W.Y.; Wong, C.Y.; Boon-Itt, S. The combined effects of internal and external supply chain integration on product innovation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 146, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachizawa, E.M.; Wong, C.Y. The performance of green supply chain management governance mechanisms: A supply network and complexity perspective. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 51, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Geng, Y. Green supply chain management in China: Pressures, practices and performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.W.Y.; Lai, K.H.; Cheng, T.C.E. Complementarities and alignment of information systems management and supply chain management. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2009, 2, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lu, C.; Haider, J.J.; Marlow, P.B. The effect of green supply chain management on green performance and firm competitiveness in the context of container shipping in Taiwan. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2013, 55, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Datta, P.P. Adoption of green supply chain management practices and their impact on performance: An exploratory study of Indian manufacturing firms. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 52, 2085–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnychenko, I.; Barontini, R.; Testa, F. Green practices and financial performance: A global outlook. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaksar, E.; Abbasnejad, T.; Esmaeili, A.; Tamošaitienė, J. The effect of green supply chain management practices on environmental performance and competitive advantage: A case study of the cement industry. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2016, 22, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P. Greening the supply chain: A new initiative in South East Asia. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 632–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniato, F.; Caridi, M.; Crippa, L.; Moretto, A. Environmental sustainability in fashion supply chains: An exploratory case based research. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Holt, D. Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic performance? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.Y.; Boon-Itt, S.; Wong, C.W.Y. The contingency effects of environmental uncertainty on the relationship between supply chain integration and operational performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K.; He, H.; Chan, H.K.; Wang, W.Y.C. Environmental orientation and corporate performance: The mediation mechanism of green supply chain management and moderating effect of competitive intensity. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaga, G.N.; Whipple, J.M.; Lynch, D.F. Examining supply chain relationships: Do buyer and supplier perspectives on collaborative relationships differ? J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffen, C.A.; Rothenberg, S. Suppliers and environmental innovation: The automotive paint process. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2000, 20, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, F.E.; Cousins, P.D.; Lamming, R.C.; Farukt, A.C. The role of supply management capabilities in green supply. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2001, 10, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Wu, Z. Building a more complete theory of sustainable supply chain management using case studies of 10 exemplars. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 45, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppelta, T.; Foerstlb, K.; Reuter, C.; Hartmann, E. Sustainability management beyond organizational boundaries–sustainable supplier relationship management in the chemical industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Gonzalez-Torre, P.; Adenso-Diaz, B. Stakeholder pressure and the adoption of environmental practices: The mediating effect of training. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.R.; Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Special topic forum on sustainable supply chain management: Introductions and reflections on the role of purchasing management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 4, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollos, D.; Blome, C.; Foerstl, K. Does sustainable supplier cooperation affect performance? Examining implications for the triple bottom line. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 2968–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañón-De-Francia, J.; Garcés-Ayerbe, C.; Ramírez-Alesón, M. Are more innovative firms less vulnerable to new environmental regulation? Environ. Resour. Econ. 2007, 36, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Schaltegger, S. The effect of corporate environmental strategy choice and environmental performance on competitiveness and economic performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2004, 22, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Rigoni, U.; Cavezzali, E. Does it pay to be sustainable? Looking inside the black box of the relationship between sustainability performance and financial performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1198–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Kasturiratne, D.; Moizer, J. A hub-and-spoke model for multi-dimensional integration of green marketing and sustainable supply chain management. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. Invited editorial: A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.V.; Fouts, P.A. A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental performance and profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 3, 534–559. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita, L.F.; Anand, J.; Brush, T.H. Comparing the resource-based and relational views: Knowledge transfer and spillover in vertical alliances. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 913–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehhi, A.; Nobanee, H.; Khare, N. The impact of sustainability practices on corporate financial performance: Literature trends and future research potential. Sustainability 2018, 2, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, P.D.; Lawson, B.; Petersen, K.J.; Fugate, B.S. Investigating green supply chain management practices and performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2019, 39, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Zhang, J. Performance of green supply chain management: A systematic review and meta analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 1064–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.Y.; Wong, C.W.; Boon-Itt, S. Integrating environmental management into supply chains: A systematic literature review and theoretical framework. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N.; Ramanujam, V. Measurement of business performance in strategy research: A comparison of approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Pieper, T.M.; Ringle, C.M. The use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in strategic management research: A review of past practices and recommendations for future applications. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (pls) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laari, S.; Töyli, J.; Solakivi, T.; Ojala, L. Firm performance and customer-driven green supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1960–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarshie, A.M.; Salmi, A.; Leuschner, R. Sustainability and corporate social responsibility in supply chains: The state of research in supply chain management and business ethics journals. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2016, 22, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rashid, S.H.; Sakundarini, N.; Ghazilla, R.A.R.; Thurasamy, R. The impact of sustainable manufacturing practices on sustainability performance: Empirical evidence from Malaysia. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.W., Jr.; Zelbst, P.J.; Meacham, J.; Bhadauria, V.S. Green supply chain management practices: Impact on performance. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandris, J.; Kalchschmidt, M. Customer pressure and innovativeness: Their role in sustainable supply chain management. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2014, 20, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzi, A.; Toniolo, S.; Manzardo, A.; Ren, J.; Scipioni, A. Exploring the direction on the environmental and business performance relationship at the firm level. Lessons from a literature review. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Gao, Y.; Koh, L.; Sutcliffe, C.; Cullen, J. The role of customer awareness in promoting firm sustainability and sustainable supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jayaraman, V.; Paulraj, A.; Shang, K. Proactive environmental strategies and performance: Role of green supply chain processes and green product design in the Chinese high-tech industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 54, 2136–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).