Past, Present and Future of Hay-making Structures in Europe

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- as part of the cultural heritage and so treated in Spatial/Environmental planning, Landscape Plans, Local Action Plans and/or Guiding Principles for local groups, serving as national icons or regional symbols in a tourism context;

- maintenance and revival of tradition during actions, events, feast and festivals;

- new uses, e.g., storage of other materials, or rebuilding into hay hotels, holiday flats, or apartments, or residential houses;

- educational value (ethnological, biological, cultural, historical, etc.);

- aesthetic value, attractiveness and inspiration for artists–literature, painting, architecture, photography or a combination thereof.

3. Results

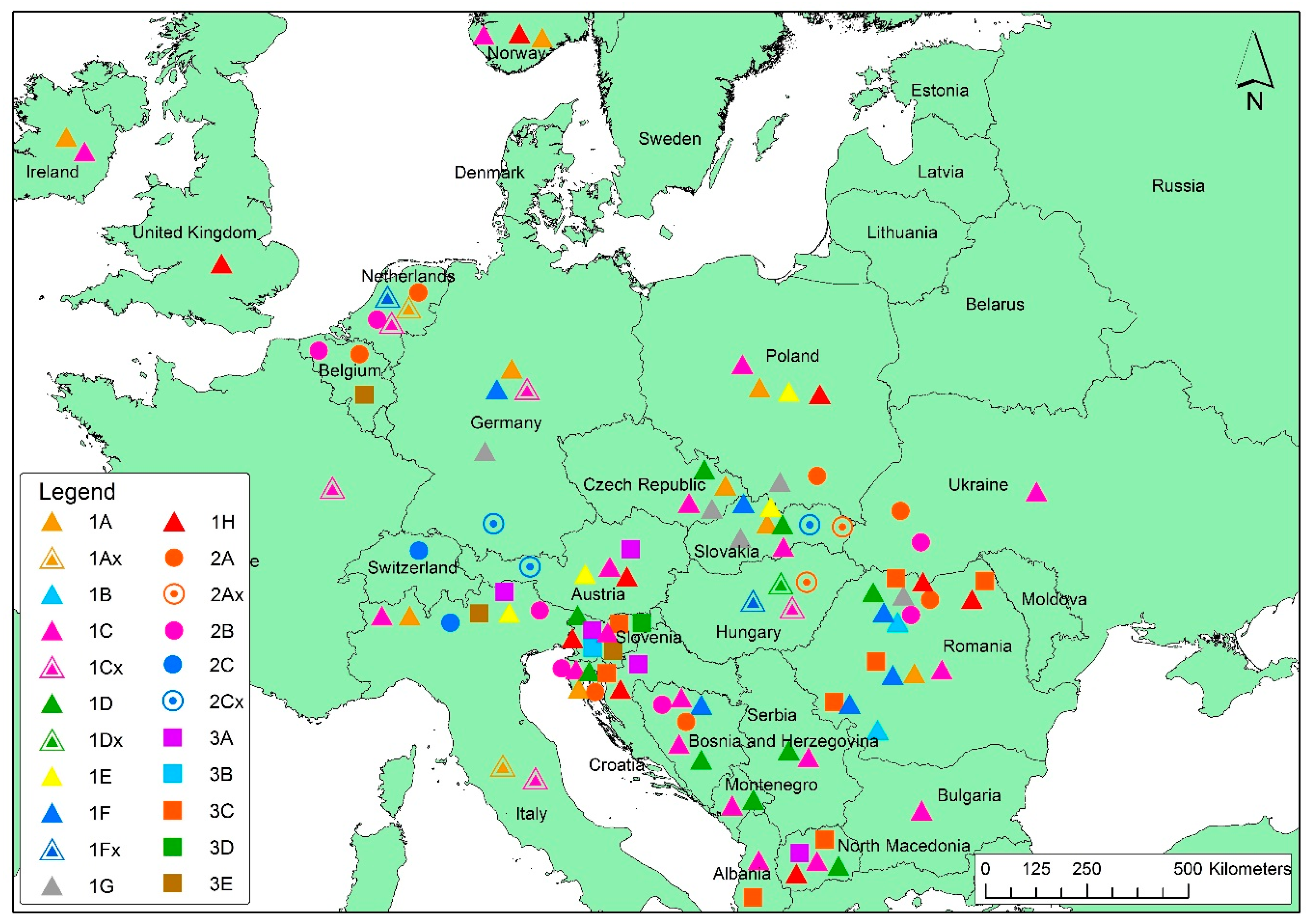

3.1. The Study Area, Regional Distribution and Terminology

3.2. The History and Typology of Hay-Making Structures

- (1)

- Temporary hayracks of various shapes were particularly widespread in most European regions for drying and temporary storage: e.g., hayracks, sticks, hay heaps, and harpfe, made from wood or metal, or with a roof made of straw, wood, or, more lately, metal (Figure 1).

- Hay heaps or haystacks are the simplest temporary structures to dry fodder in the field, built on a wood pile. Haystacks or haycocks are nothing more than heaps of hay. They may or not have staggered wooden peds (Figure 1 (1A,1B)), or they may have some larger wooden frame over which the hay is draped. One type of construction consists of a three to five meters tall spruce or hardwood stake or pole, in some cases with side branches or smooth stake with cross pin (Figure 1 (1C,1D,1E)); another is tripod – a frame consisting of a loose construction of three poles, with the base placed in a triangle shape and bound together at the tops, with horizontal poles bound between the vertical poles (Figure 1 (1F)); or pyramidal stands with multiple horizontal battens (Figure 1 (1G)). Sometimes hay is simply piled around a tree. Haystacks are also called haycocks in some dialects of English, or sometimes stokes, shocks, or ricks. They are still very common in many regions, e.g., in Italy (especially in the plane area), Slovakia, Romania, Ukraine and Germany.

- Simple hayracks can be found in the Alpine region (Austria, Italy, Slovenia) and also in Northern (Norway) and Central Europe (Poland, Romania—especially in Maramures). In the traditional design, these structures are made of wood, with two (or more) vertical columns (arfis) and horizontal beams forming the rack on which the fodder leans (perties) (Figure 1 (1H)). In more recent constructions, the horizontal sticks were replaced by strings of steel, and the vertical columns by concrete. The grass was hung on the horizontal sticks or wires. The grass had to be shaken well before being hanged up, often with a hayfork, in thin layers. A wooden rake was used to gather the grass on the ground.

- (2)

- Hay barracks are a special type of hay shelters that are built around one to six, but usually four upright wooden posts, and serve to store large amounts of hay (Figure 2). The original wooden hay barrack had the most elaborate design and greatest variation in the Netherlands. Hay is stacked from the fields under the hay barrack, and removed later during the foddering season. The roof can slide up and down and is locked in place with pegs according to the amount of hay, a feature historically called also a Dutch roof (Figure 2 (2A,2B)). They have been maintained in many parts of the Netherlands, but are ever less frequently used for their original purpose. They are also widespread in Germany, Romania and Flanders (where they are sometimes called ‘Dutch’) [35], used to exist also in England (imported from the Netherlands; but are no longer used) [35], Italy, Croatia, Bosnia, Poland, Baltics, Belorussia, Czechia, Slovakia and Ukraine. Zimmermann mentions an earlier occurrence of hay barracks in Scandinavia, with the name ‘helm’ [22]. Outside Europe they are present in the United States and in Canada. The name ‘barrack’ itself is a North American derivate of the Dutch ‘berg’ [36]. Several modernizations and inventions have taken place in the hay barracks themselves as well as in handling hay. For example, the Jacob’s ladder for hay transporting, the hay grab and the pneumatic hay conveyer (with suction hose and combined with an electric ventilation system) were all developed by the seventies.Haylofts or block huts (Figure 2 (2C)) are small block huts, generally placed in the highest and most remote meadows. They were used to store hay until the snowfalls, in order to transport hay by sledge. They were widely spread in Carpathian (Slovakia, Romania) and in the Austrian, Italian and Swiss Alps (Figure 3). Today only few are still in use and either have been abandoned (Carpathians), or are used for leisure purposes (Alps). Comparable stone-built buildings for hay storage exist in the Pennines in England.

- (3)

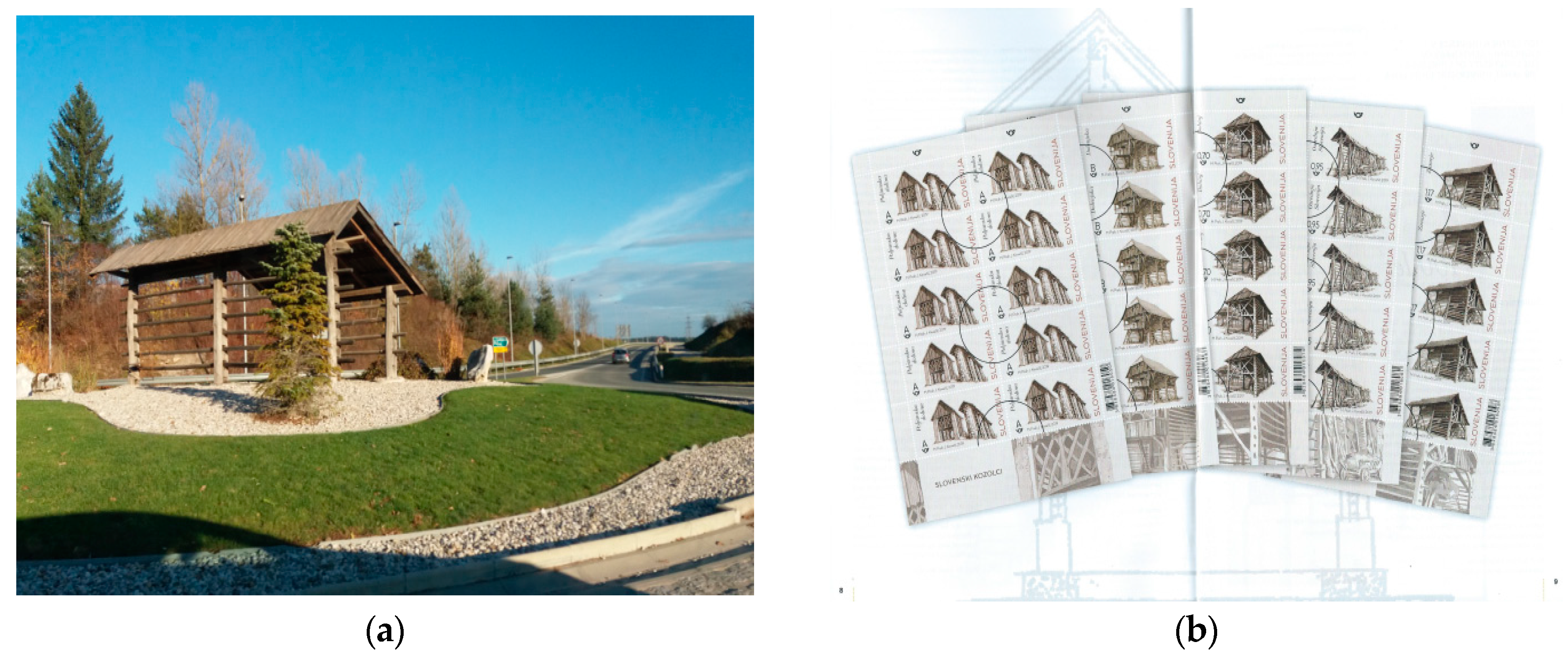

- In addition to temporary hayracks or permanent hay barracks, different types of other permanent constructions, including buildings in the hay meadows (thus not within the farm or close to it), for drying and storing hay all year round—single or double stretched hayracks—were widespread in the Alps (Figure 2). In addition to hay drying, these constructions may also serve other purposes, such as storing hay, straw and some other produce, or sheltering farm-carts, agricultural tools, timber, etc. Different variants of hayracks exist, fulfilling these two functions to various degrees. The range of these two functions comprises all the typical versions of hayrack. The function of these structures is the best starting point for classifying hayracks, as it not only explains the several characteristic forms but also relates to their origin and evolution. The hayrack or kozolec (harpfe, arfa, favèr, favàs) is a simple wooden construction for drying hay, retaining an archaic mode of building. The structures have a roof, originally made of straw but, later of wooden, and more recently metal tiles. More than thirty different types can be distinguished on the basis of their construction, most of them found only in Slovenia, the southernmost part of Austria and Northeastern Italy [37,38]. In the Dolomites these structures were used for drying fava beans [39]. After Alpine agriculture started specialising in cattle breeding in the beginning of the 20th century, turning arable land into meadows as a consequence, they were used to dry hay. Hayracks on steep slopes are single stretched (Figure 2(3A)), with supports if necessary. Double (Figure 2(3B)) or stretched hayracks (Figure 2(3E)) can consist of many “windows”, or have a projecting roof attached to one “window” for the protection of carts and people from sudden downpours. Double stretched hayracks (Figure 2(3B–3E)) are built when windy conditions created a need for additional stability. Later, when building techniques advanced, there was a tendency to give outbuildings several economic functions. This resulted in the invention of the linked hayracks “toplarji” to accommodate rational storage of the more abundant and diverse harvest (Figure 2(3C,3D)).

3.3. The Distribution of Hay-Making Structures

3.4. Present and Future of Hay-Making Structures, Their Value

- The Lammertaler HayART Festival in Austria, which developed from the traditional Lammertaler hay festival into a famous and very successful art festival. Artists process more than 1 ton of hay to artwork at the world’s largest hay sculpture parade, HayART Corso is accompanied by horses, vintage tractors, bands, Schnalzern and costume groups from the Lammertal communities as well as a gourmet and handicraft market. The festival is visited by travelers from other regions or countries (e.g., Germany).

- Hay sculpture exhibition “Fête du Fête du moine” Bellelay/Switzerland; 20.000 visitors within the first month in 2018 [48].

- Many Festivals in Friuli Venezia Giulia Region/Italy, “hay bucking” competitions (for example “Fasin la Mede”).

- Cultural heritage related to hay-making also includes a type of folk songs, called “travnice”, which were sung on the mountain meadows in Slovakia.

- Competitions in grass cutting (by hand) exist in Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and South Tyrol.

- EtnoTour and many other festivals of grass mowing, using scythes, in Slovenia.

- International Hay-making Festival in Gyimesbükk (Eastern Carpathians, Romania), with the aim to present the landscape of the Gyimes Valley, and the traditional lifestyles of the Csángó people, enabling participants to take part in their traditional hay-making activities.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lesschen, J.P.; Elbersen, B.; Hazeu, G.; van Doorn, A.; Mucher, S.; Velthof, G. Task 1—Defining and Classifying Grasslands in Europe. In Final Report March 2014; Alterra, Part of Wageningen UR: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffbeck, S.R. The Haymakers: A Chronicle of Five Farm Families, 1st ed.; Minnesota Historical Society Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2002; p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Ivașcu, C.M.; Öllerer, K.; Rákosy, L. The Traditional Perceptions of Hay and Hay-Meadow Management in a Historical Village from Maramureş County, Romania. Martor J. 2016, 21, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Babai, D.; Molnar, Z. Small-scale traditional management of highly species-rich grasslands in the Carpathians. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 182, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasenapp, M.; Thornton, T.F. Traditional ecological knowledge of Swiss Alpine farmers and their resilience to socioecological change. Hum. Ecol. 2011, 39, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingrich, S.; Krausmann, F. At the core of the socio-ecological transition: Agroecosystem energy fluxes in Austria 1830–2010. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baessler, C.; Klotz, S. Effects of changes in agricultural land-use on landscape structure and arable weed vegetation over the last 50 years. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 115, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezák, P.; Mitchley, J. Drivers of change in mountain farming in Slovakia: From socialist collectivization to the common agricultural policy. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2014, 14, 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicik, I.; Jelecek, L.; Stepanek, V. Land-use changes and their social driving forces in Czechia in the 19th and 20th centuries. Land Use Pol. 2001, 18, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druga, M.; Faltan, V. Influences of Environmental Drivers on Land Cover Structure and Its Long-Term Changes: A Case Study of the Villages of Malachov and Podkonice in Slovakia. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2014, 22, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard, F.; Petit, S.; Smith, G.; Thomson, A.; Brown, N.; Manchester, S.; Wadsworth, R.; Bugar, G.; Halada, L.; Bezák, P.; et al. Land cover change in Europe between 1950 and 2000 determined employing aerial photography. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2010, 34, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finch, H.J.S.; Samuel, A.M.; Lane, G.P.F. Conservation of grass and forage crops. Lockhart & Wiseman’s Crop Husbandry Including Grassland, 9th ed.; Finch, H.J.S., Samuel, A.M., Lane, G.P.F., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2014; pp. 513–526. [Google Scholar]

- Südtirol News. Österreich: Heumilch 2017 deutlich stärker als Gesamtmarkt gewachsen. Südtirol News, 30 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- EUCALAND, About|FEAL EAtlas. 2017. Available online: http://feal-future.org/eatlas/en/node/17 (accessed on 29 November 2018).

- Centeri, C.; Renes, H.; Roth, M.; Kruse, A.; Eiter, S.; Kapfer, J.; Santoro, A.; Agnoletti, M.; Emanueli, F.; Sigura, M.; et al. Wooded Grasslands as Part of the European Agricultural Heritage. In Biocultural Diversity in Europe; Agnoletti, M., Emanueli, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 75–103. [Google Scholar]

- Imrichová, Z. Impact of management practices on diversity of grasslands in agricultural region of middle Slovakia. Ekologia (Bratislava) 2006, 25, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cvitanovic, M.; Lucev, I.; Furst-Bjelis, B.; Borcic, L.S.; Horvat, S.; Valozic, L. Analyzing post-socialist grassland conversion in a traditional agricultural landscape—Case study Croatia. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 51, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabuk, A.; Mojses, M.; Halabuk, M.; David, S. Towards Detection of Cutting in Hay Meadows by Using of NDVI and EVI Time Series. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 6107–6132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EUROSTA Land Cover Overview by NUTS 2 Regions. Eurostat—Data Explorer. 2015. Available online: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- Feranec, J.; Soukup, T.; Hazeu, G.; Jaffrain, G. European Landscape Dynamics: CORINE Land Cover Data; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2016; p. 337. [Google Scholar]

- EEA. Biogeographical Regions, European Environment Agency. 2016. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/biogeographical-regions-europe-3 (accessed on 30 November 2018).

- Zimmermann, W. The ‘helm’ in England, Wales, Scandinavia and North America. Vernac. Archit. 1992, 23, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, M. Istrian Cattle; v Štifanić, A., Kovač, M., Eds.; Istrian Cattle a Monograph: Višnjan, Croatia, 1999; pp. 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bassetti, S.; Morello, P. Paesaggio e Architettura Rurale Nelle Valli Ladine Delle Dolomiti; Banca di Trento e Bolzano: Trento, Italy, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gellner, E. Architettura Rurale Nelle Dolomiti Venete; Dolomiti: Cortina, Italy, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bele, B.; Norderhaug, A. Traditional land use of the boreal forest landscape: Examples from Lierne, Nord-Trøndelag, Norway. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. Norsk. Geogr. Tidsskr. 2013, 67, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Važanová, J. Review of Trávnice. Lúčne piesne na Slovensku: Ku genéze, štruktúre a premenám piesňového žánru [Trávnice. The Meadow Songs in Slovakia: A Contribution to the Origins, Structure, and Transformations of a Song Genre], Hana Urbancová. World Music 2009, 51, 162–165. [Google Scholar]

- Bujanda Miguel, M. Varieties of maize aerial drying sheds across Europe. Arhit. Raziskave Archit. Res. 2014, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Evensen, H.P.E. Slå Med Ljå; Sollia Forlag: Oslo, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Juvanec, B. Kozolec; Fakulteta za arhitekturo: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2007; p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Mušič, M. The Architecture of the Slovene “kozolec” (hay rack). Architektura Slovenskega Kozolca; Cankarjeva založba: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1970; p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Podolák, J. Pestovanie poľnohospodárskych plodín a chov hospodárskych zvierat na Slovensku od polovice 19. do polovice 20. storočia. Agrikultúra 1965, 4, 29–77. [Google Scholar]

- Skre, B.G. Havråboka—Soga om ein Gamal Gard på Osterøy; Stiftinga Havråtunet: Osterøy, Norway, 1994; p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens, S.M. Paalschuren in Vlaanderen. Land Zicht 2006, 75, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, N. A History of Farm Buildings in England and Wales; David & Charles: Newton Abbot, UK, 1984; p. 279. [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens, S.M. A Terminological Approach to the History and Dissemination of Hay Barracks and Stacks. 2019; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Melik, A. Kozolec na Slovenskem; Znanstveno društvo: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1931; p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Čop, J.; Cevc, T. The path of cultural heritage. Slovenski Kozelec. Slovene hay-rack, Book Series; AGENS d.o.o. Žirovnica: Žirovnica, Slovenija, 1993; p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- Baragiola, A. La Casa Villereccia delle Colonie Tedesche del Gruppo Carnico Sappada, Sauris Timau, con Raffronti delle Zone Contermini Italiana e Austriaca Carnia, Cadore, Zoldano, Agordino, Carintia e Tirolo; Drucker: Padova, Italy, 1915. [Google Scholar]

- Lieskovský, J.; Kenderessy, P.; Špulerová, J.; Lieskovský, T.; Koleda, P.; Kienast, F.; Gimmi, U. Factors affecting the persistence of traditional agricultural landscapes in Slovakia during the collectivization of agriculture. Landsc. Ecol. 2014, 29, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicolson, A. Hay. Beautiful. National Geographic Magazine. 2013. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2013/07/transylvania-hay/ (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Balassa, I.; Ortutay, G. Hungarian Ethnography and Folklore; Corvina: Budapest, Hungary, 1979; p. 747. [Google Scholar]

- Iceland Review. Heuexport verfünffacht. Iceland Review, 29 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Žarkovič, V. The Land of Hayracks. The First Open-Air Hayrack Museum in the World. 2012. Available online: http://www.slovenia.si/culture/tradition/the-land-of-hayracks (accessed on 4 January 2019).

- Negraru, A.; Sima, E.; Iuga, A. Fânul ca element de patrimoniu în satul Șurdești. Între tradiție și modernitate. (Hay as element of heritage in the village Șurdești. Between tradition and modernity). Cybela 2005, 1, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Slovenski Etnografski Muzej. Kozolec|Slovenski Etnografski Muzej. 2019. Available online: https://www.etno-muzej.si/en/digitalne-zbirke/kljucne-besede/kozolec (accessed on 4 January 2019).

- Stichting Kennisbehoud Hooibergen Nederland. 2016. Available online: https://www.hooidelta.nl (accessed on 7 July 2019).

- Tausende Besuchen Heuskulpturen-Ausstellung. Landwirtschaftlicher Informationsdienst LID.CH. 2018. Available online: https://www.lid.ch/agronews/detail/news/tausende-besuchen-heuskulpturen-ausstellung/ (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- Stichting Kennisbehoud Hooibergen Nederland. Het Nederlands Hooiberg Museum. On line Haymusea and Foundations in the World. 2016. Available online: http://www.hooiberg.info/?page=hayworld (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Ritch, A. Hay in Art: Introduction to the Hayinart Database. 2004. Available online: http://www.hayinart.com/000319.html (accessed on 30 November 2018).

- Bartha, E. Nature in the City. Martor 2016, 21, 188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, D.G. Hay Barracks in Newfoundland. Mater. Cult. Rev. 2013, 77/78, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens, S.M. Paalschuren in Vlaanderen en Wallonië. Land Zicht 2007, 76, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens, S.M. Hooibergen en vloedschuren in het Gelders rivierengebied. His-Torisch-Geogr. Tijdschr. 1993, 11, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, A.G. The Hay Barrack: Form and Function of a Relict Landscape Feature. J. Cult. Geogr. 1985, 5, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuga, A. Intangible hay heritage in Șurdești. Martor 2016, 21, 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlström, A.; Iuga, A.; Lennartsson, T. Managing biodiversity rich hay meadows in the EU: A comparison of Swedish and Romanian grasslands. Environ. Conserv. 2013, 40, 194–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, A.; Paulowitz, B. UNESCO World Heritage as an opportunity for mountain landscapes - a trigger for development not only in the Alps. TÁJÖKOLÓGIAI LAPOK J. Landsc. Ecol. 2018, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Raducan, V. Land Art and Agriculture. Sci. Pap.-Ser. B-Hortic. 2012, 56, 381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, R.J.F.; Riley, M. Traditional Ecological Knowledge from the internet? The case of hay meadows in Europe. Land Use Pol. 2018, 70, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caluseru, A.L.; Cojocariu, L.; Borlea, F.; Bordean, D.-M.; Horablaga, A. Rural Development of Mountain Areas in Romania, Challenges and Targets for the Year 2020. In Ecology, Economics, Education and Legislation, Volume II; Stef92 Technology Ltd.: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2015; pp. 791–797. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, B. Mountain Hay Meadows: Hotspots of Biodiversity and Traditional Culture. Society of Biology, London. Pogány-havas Association. 2011. Available online: https://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/ (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Orlandi, S.; Probo, M.; Sitzia, T.; Trentanovi, G.; Garbarino, M.; Lombardi, G.; Lonati, M. Environmental and land use determinants of grassland patch diversity in the western and eastern Alps under agro-pastoral abandonment. Biodivers. Conserv. 2016, 25, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, O.; Cousins, S.A.O. Historical Landscape Perspectives on Grasslands in Sweden and the Baltic Region. Land 2014, 3, 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázsi, Á. Grassland management in protected areas—Implementation of the EU biodiversity strategy in certain post-communist countries. Hacquetia 2018, 17, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongepierova, I.; Mitchley, J.; Tzanopoulos, J. A field experiment to recreate species rich hay meadows using regional seed mixtures. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 139, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D.A.; Lindsay, K.E.; Brook, R.W. Risk of Agricultural Practices and Habitat Change to Farmland Birds. Avian Conserv. Ecol. 2011, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribic, C.A.; Guzy, M.J.; Sample, D.W. Grassland Bird Use of Remnant Prairie and Conservation Reserve Program Fields in an Agricultural Landscape in Wisconsin. Am. Midl. Nat. 2009, 161, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcakova, I.; Gazzola, P.; Pauditsova, E. Public Participation and Sustainable Landscape Management. In Landscape Impact Assessment in Planning Processes; Walter De Gruyter Gmbh: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 112–138. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, C.G. Barns of New York: Rural Architecture of the Empire State; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2012; p. 298. [Google Scholar]

| Grassland Cover (%) [19] | Biogeographical Region [21] | Local Regional Name for Hay-making Structures | Present State, Management and Other Particularities of Hay-making Structures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria (AT) | 24.7 | Continental Alpine | heubarge = hay barrack, triste = hay pile | Hay-making structures are preserved in the mountains but only where machines cannot be used, permanent structures are mostly abandoned. Connected to transhumance in the Alps, “Winterheuzug” = common work of men (during World War I also women) to transport the hay down to the valley in January. Some small plots in the mountains are used to provide fresh hay for wild animals that would otherwise damage the forest by eating small trees. |

| Belgium | 31 | Atlantic Continental | veldschuur, Hollandse schuur, engelse schuur, schuiver, hooischuur, (Engelse) mijt = hay barrack | The hay barrack in Flanders is a reintroduction, as is shown by the names that are not derived from the old ‘berg’ names [22]. Flemish hay barracks are called ‘paalschuur’ in literature, but that is an artificial name. In Wallonia the hay barrack can be found in the mountainous area. |

| Bosnia | Alpine Continental Mediterranean | broch, oborog, oborih = hay barrack | Existed in the Banja Luka region, but no longer in use. They were owned only by immigrants originally from Czechia, but who had moved to Ukraine before immigrating in Bosnia. Haystacks with a central pole and tripods for drying hay are common in Bosnia. | |

| Czechia | 22.3 | Continental Pannonian | sušák sena = hay drying structure, kopa, kůpa, kopka, kopice, kopen, kopenec = haystack, svinka, svině = extended haystack like pig, kůly, trojáky, štangle, Áčka = wooden hay stick, ostrva = wooden hay structrure, oboroh, brah = hay barrack | Traditional haymaking is disappearing and being replaced by hay bales. A few examples can be found due to efforts to preserve traditions (hay-making camps and festivals) and biodiversity protection (NGO, nature conservation bodies). Nowadays hay barracks are only to be found in open air museums (skansen). |

| Croatia | Mediterranean | trtoja, tetoja = hay barrack, kopa, rasa, kvaka, ostrva = haystack with central pole, lomnica = hay heap, plast, plastič, stog = hay heap | Still in use in Istria, although diminishing as farming is no longer profitable. Everything changed after 1990. By 1999, almost 80% of the former farming area (which covered nearly all of Istria) was no longer cultivated [23]. | |

| France | 26.7 | Atlantic Mediterranean | les structures de fenaison = Hay-making structures, mule de foin = haystacks, meule carrée = hay barrack | Hay-making still exists, but has lost its former importance. Today, hay balls or, more often, silage balls wrapped in plastic are mostly used. |

| Germany | 21.9 | Atlantic Continental | heuschober = haystack, heuballen = hay bale, rundballen = round bales, heuwiese = hay meadow, heuboden = hayloft, heuberg, barg = hay barrack | Hay production is present all over the country, though now mainly for horse keeping and small pets, mostly mechanised, with rectangular or round bales, the latter being increasingly popular. Only on very steep slopes, or for heritage and/or biodiversity preservation reasons, is grass cut manually. Nowadays only a few modernized hay barracks survive, apart from those in open air museums. Several side products: Heutee = hay tea, Heuhotel = Hay hotel, hay considered to have both health and natural value, festivals with hay sculptures, thanksgiving feasts |

| Hungary | 19.9 | Pannonian | abora = hay barrack, szénakazal = haystack, hay heap, szénaboglya, boglya = haystack, szénabála = hay bale, körbála = round bale, kockabála = cubic bale, szénakunyhó = hay storage shack | The majority of the structures is on the plains and related to intensive agriculture. However, small haystacks appear all over the country, related mostly to small, extensive farms. These were used on the field until the end of the 20th century for collecting hay from smaller areas, subsequently to be taken into the yard of a farm. There it was piled up in one or two bigger haystacks (3–5 m high). Today these occur only occasionally, in the hillsides and in the mountainous areas. Machine produced hay balls covered with plastic are increasingly used. Hay barracks were once present in the Upper Tisza region. Nowadays they are found only in open air museums (skansen). |

| Italy | 21.7 | Alpine Continental | meda (de fen) = haystack with central pole, covone = hay stick, harpfe, arfa, favèr, kèisn, kozolec = hay stack, liguria: barc(o) = hay barrack, scapita, barc = hay barrack, baita, barco, stali = small hay storage, hayloft, tabià = hay storage | In the Alps, most of the permanent hay structures are preserved; they are part of the traditional mosaic landscape, but today, they are rarely used for haymaking. In the Dolomites, tabià are permanent wooden barns (hay drying + storage + cowshed), dispersed on the meadows, to be used in the intermediate seasons, and often placed along the way to the summer pastures. They are often still in use [24,25]. Barchi and mede in Veneto still partly in use, barchi sometimes to store round bales. Liguria: nowadays no longer in use. Friuli: no more hay barracks, all gone |

| The Netherlands | 36.3 | Atlantic | opper = hay heap, hooimijten, schelven, klampen, ruiters = temporary structures, hooibergen, hooischuren = permanent structures for hay storage, steltenberg, stoltenberg, schuurberg = hay barrack with raised floor and extensions to the side | Specialised hay meadows have mainly disappeared. Some former ‘water meadows’ as well as ‘blue grasslands’ and other species-rich grasslands have been preserved, mainly for ecological purposes. Hay was and is extremely important in the Netherlands, not only for the abundant dairy cows and, formerly, draught and war horses but also for export. Grass in the peat and clay areas was and still is often of excellent quality. There may have been a few hundred thousand hay barracks in the 19th and early 20th century (not only for the storage of hay, though); now there are no more than around 5,000 left, which are seldom used for their original purpose if used at all. |

| Norway | 19.4 | Boreal | høysåte, høystakk = stack, hesjestaur = wooden stick, hesje = drying rack, treraje = horizontal stick, luovvo = haystack on a platform | Before 1900 hay was mostly harvested from outfields, mainly on forest and mountain grasslands, while infields were reserved for growing cereals. Later on, hay fodder was also been produced on infields [26]. Special techniques (e.g., zip-lines for downhill transport of hay from meadows to barns) and several types of permanent and semi-permanent structures existed. Luovvi are used by Saami people. |

| Poland | 22.6 | Continental Alpine | kopa siana, kopka = hay stack, ostrew, stóg siana = hay stick, wiazka siana – hay sheaves, hay ball, bróg = hay barrack | Small-scale mosaic landscape of grassland and arable land is still preserved. Special method of making hay stack by “wiazka siana”. Hay barrack are nowadays no longer in use. |

| Romania | 27.1 | Alpine Continental Pannonian Stepic | şopron/şopru, fânar, șură, colibă de fân = (hay) barrack, claie, clanie, șiră, stog = haystack (with central pole), par de claie, rudă de claie, prepeleac, perpeleac, țăpăruie = the pole of a haystack, germană = haycock tripod, capră, gard, capră colibă = hay drying rack, căpiţă, poșori, porșori, porconi, porcoi, boghiuri = hay heap, haycock, jărăzi, jirezi = simple hayrack, colibă = temporary shack, mărginătură = gathered hay, but not piled into a stack or haycock, podină, fundurei, vatră – pieces of wood and branches with leaves that are put around the hay stack pole and on which the haystack is built, pătul – a pollarded birch or beech tree, with only some branches left to grow, in which a haystack was built, balot = hay bale, Hungarian regional names from Transylvania and Maramureș, szénakunyhó, gunyhó = hay storage shack szénaszárító állvány, kecske, bak = hay drying rack, ösztörü, üsztürü, csereklye = branched rack for drying hay in stacks, szénaboglya, boglya = haystack, szénabála, bála = hay bale | Hay barracks and various temporary shacks are still in use in the Romanian Carpathians (mainly in Maramureş, Transylvania), although diminishing. These mountain regions were never very influenced by Ceauşescu’s agricultural policy of intensification and large-scale farming, thanks to their remoteness and isolation. Haystacks are common in Romania [3], but in hilly areas and in the lowlands tend to be replaced by hay bales, wrapped in plastic. |

| Slovakia | 19.5 | Alpine Pannonian | ostrva, koly = wooden hay stick, kopy, stohy sena (petrenec, kopenec, navidľa, kozák, babiak) = local/regional names for haystack, hayrack, oborohy = hay barracks, senník = hayloft | Preserved only on small scale farmland, on high steep slope unsuitable for machinery. They are part of the cultural heritage: there is related genre of traditional folk songs called “travnice“ [27]. Nowadays, hay barracks are only to be found in open air museums (skansen). |

| Slovenia | 21.7 | Alpine (Dinaric) Continental Pannonian | ostrv = wooden hay stick, senena kopa (kopica) = haystack, ostrnica/preprosti kozolec = hay sticks/simple hayrack, kozolec (kozovc, kozuc) = hayrack, kozolec brez strehe = hayrack without roof, enojni kozolec = single hayrack, stegnejni kozolec = simple stretched hayrack, kozolec s plaščem = hayrack with “cloak”, dvojni kozolec = double hayrack, toplar = coupled hayrack, kozolec na kozla = “goat” hayrack, prislonjeni kozolec = leaned hayrack, leseni kozolec = wooden hayrack, zidani kozolec = stoned/built up hayrack, senik = hayloft, bale = round bales | Slovenia is called “the land of the hay racks (Dežela kozolcev). Hay racks are widely preserved as a part of the traditional mosaic landscape. With the advent of new techniques in preparing fodder for livestock they are rapidly losing importance, so they are decaying or changing their purpose. They are still very popular as decoration and some of them are being adapted for habitation or purposes of tourism, or even newly constructed for these purposes. The surface area of meadows increased after abandoning fields due to decreased self-sufficiency. The meadows are still widely in use, especially due to the growing importance of stockbreeding; pastures are exposed to afforestation. |

| Switzerland | Alpine Continental | heuberge = haystack | Still in use in some remote areas in central Switzerland (“Heuberge”), theme trails exist. | |

| Ukraine | Alpine Continental Steppic | oborih = hay barrack | Hay barracks are widespread in Western Ukraine, but are present elsewhere as well. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Špulerová, J.; Kruse, A.; Branduini, P.; Centeri, C.; Eiter, S.; Ferrario, V.; Gaillard, B.; Gusmeroli, F.; Jurgens, S.; Kladnik, D.; et al. Past, Present and Future of Hay-making Structures in Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5581. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205581

Špulerová J, Kruse A, Branduini P, Centeri C, Eiter S, Ferrario V, Gaillard B, Gusmeroli F, Jurgens S, Kladnik D, et al. Past, Present and Future of Hay-making Structures in Europe. Sustainability. 2019; 11(20):5581. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205581

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠpulerová, Jana, Alexandra Kruse, Paola Branduini, Csaba Centeri, Sebastian Eiter, Viviana Ferrario, Bénédicte Gaillard, Fausto Gusmeroli, Suzan Jurgens, Drago Kladnik, and et al. 2019. "Past, Present and Future of Hay-making Structures in Europe" Sustainability 11, no. 20: 5581. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205581

APA StyleŠpulerová, J., Kruse, A., Branduini, P., Centeri, C., Eiter, S., Ferrario, V., Gaillard, B., Gusmeroli, F., Jurgens, S., Kladnik, D., Renes, H., Roth, M., Sala, G., Sickel, H., Sigura, M., Štefunková, D., Stensgaard, K., Strasser, P., Ivascu, C. M., & Öllerer, K. (2019). Past, Present and Future of Hay-making Structures in Europe. Sustainability, 11(20), 5581. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205581