Who Values Corporate Social Responsibility in the Korean Stock Market?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. The Unique KRX Dataset

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Estimation of Abnormal Returns

3.2.2. Measuring Changes in Risk and Liquidity

3.2.3. Analysis of Investors’ Trading Behavior

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Effects of Inclusion in CSR Indices

4.2. Changes in Risk and Liquidity

4.3. Trading Activities of Investor Groups

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carroll, A.B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.; Helland, E.; Smith, J. Corporate Philanthropic Practices. J. Corp. Financ. 2006, 12, 855–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, C.; Comincioli, N.; Poddi, L.; Vergalli, S. Measure the Performance with the Market Value Added: Evidence from C SR Companies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, P.L.; Wood, R.A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, A. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Signaling Device for FDI. Int. J. Econ. Bus. 2006, 13, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, I.; Akathaporn, P.; McInnes, M. An Investigation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reputation and Economic Performance. Account. Organ. Soc. 1993, 18, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. Value-enhancing capabilities of CSR: A brief review of contemporary literature. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pava, M.; Krausz, J. The association between corporate social responsibility and financial performance: The paradox of social cost. J. Bus. Ethics 1996, 15, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.J.; Welker, M. Social disclosure, financial disclosure and the cost of equity capital. Account. Organ. Soc. 2001, 26, 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupperle, K.E.; Carroll, A.B.; Hatfield, J.D. An Empirical Examination of the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 446–463. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S.; Brooks, C.; Pavelin, S. Corporate Social Performance and Stock Returns. Financ. Manag. 2005, 35, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langbein, J.; Posner, R. Social Investing and the Law of Trusts. Mich. Law Rev. 1980, 79, 72–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.; Ferris, S. Agency Conflict and Corporate Strategy: The Effect of Divestment on Corporate Value. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, G.J.; Buchholz, R.A. Corporate Social Responsibility and StockMarket Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1978, 21, 479–486. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, J.J.; Mahon, J.F. The corporate social performance and corporate financial performance debate: Twenty-five years of incomparable research. Bus. Soc. 1997, 36, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, S.H.; Welch, I.; Wazzan, C.P. The Effect of Socially Activist Investment Policies on the Financial Markets: Evidence from the South African Boycott. J. Bus. 1999, 72, 35–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Value. Korea Secur. Assoc. 2009, 38, 507–545. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. Analysis of Performance of SRI index. Korean J. Financ. Eng. 2011, 10, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J. Performance of SRI in the Korean stock market: With focus on KRX SRI Index. Int. Area Stud. Rev. 2013, 17, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ok, Y. Influence of Incorporation into the KRX SRI Eco on Corporate Value. Logos Manag. Stud. 2013, 11, 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M. Relation between Corporate Social Responsibility, Governance Structure, and Cost of Capital. Korea Int. Account. Assoc. 2013, 51, 335–356. [Google Scholar]

- Consolandi, C.; Jaiswal-Dale, A.; Poggiani, E.; Vercelli, A. Global Standards and Ethical Stock Indexes: The Case of the Dow Jones Sustainability SToxx Index. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, M.; Moran, D. Impact of the FTSEGood Index on firm price: An event study. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 82, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, P.; Lapointe, V. How performance of risk-based strategies is modified by socially responsible investment universe? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2014, 38, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeszczynski, J.; McIntosh, G. Performance of portfolios composed of British SRI stocks. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, A.; Osthoff, P. The effect of socially responsible investing on portfolio performance. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2007, 13, 908–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Li, H.; Li, S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Stock Price Crash Risk. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 65, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, H.H.; Ang, W.R.; Smyth, R. Performance and performance persistence of socially responsible investment funds in Europe and North America. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2015, 34, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Ciciretti, R.; Dalo, A.; Herzel, S. Socially responsible and conventional investment funds: Performance comparison and the global financial crisis. Appl. Econ. 2015, 47, 2541–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, H. The effect of social screening on bond mutual fund performance. J. Bank. Financ. 2016, 67, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, M.; Yamaguchi, K.; Takeuchi, K. Can SRI funds better resist global financial crisis? Evidence from Japan. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2016, 48, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelle-Blancard, G.; Monjon, S. The performance of socially responsible funds: Does the screening process matter? Eur. Financ. Manag. 2014, 20, 494–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, P.; Cortez, M. Performance of European socially responsible funds during market crises: Evidence from France. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2015, 40, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, K.; Rößle, F.; Walkshäusl, C. Socially responsible, green, and faith-based investment strategies: Screening activity matters! Financ. Res. Lett. 2016, 16, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nainggolan, Y.; How, J.; Verhoeven, P. Ethical screening and financial performance: The case of Islamic equity funds. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinks, P.J.; Scholtens, B. The opportunity cost of negative screening in socially responsible investing. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, B. Do socially responsible investment policies add or destroy European stock portfolio value? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.; Koedijk, K.; Otten, R. International evidence on ethical mutual fund performance and investment style. J. Bank. Financ. 2005, 29, 1751–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.; Otten, R.; Rad, A. Ethical Investing in Australia: Is There a Financial Penalty? Pac. Basin Finance J. 2006, 14, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diltz, J.D. Does Social Screening Affect Portfolio Performance? J. Invest. 1995, 4, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzmark, S.; Sussman, A. Do Investors Value Sustainability? A Natural Experiment Examining Ranking and Fund Flows. J. Financ. 2019, 74. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibikunle, G.; Steffen, T. European green mutual fund performance: A comparative analysis with their conventional and black peers. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofsinger, J.; Varma, A. Socially responsible funds and market crises. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 48, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.; Mirza, N.; Naqvi, B.; Fu, M. Comparative risk adjusted performance of Islamic, socially responsible and conventional funds: Evidence from United Kingdom. Econ. Model. 2017, 66, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelli, C.; Viviani, J.L. Financial performance of socially responsible investing (SRI): What have we learned? A meta-analysis. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2015, 24, 158–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statman, M. Socially Responsible Mutual Funds. Financ. Anal. J. 2000, 56, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Faff, R.; Gharghori, P. The financial performance of socially responsible investments: Insights from the Intertemporal CAPM. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 146, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, V.A.; Garcia, A.; Rodriguez, L. Sustainable Development and Corporate Performance: A study Based on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliwinski, P.; Lobza, M. Financial performance of socially responsible indices. Int. J. Manag. Econ. 2017, 53, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pizzutilo, F. Measuring the under-diversification of socially responsible investments. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2017, 24, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RobecoSAM Home Page. Available online: https://www.robecosam.com/csa/indices/djsi-index-family.html (accessed on 25 June 2019).

- Brown, S.; Warner, J. Using daily stock returns: The case of event studies. J. Financ. Econ. 1985, 14, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amihud, Y.; Mendelson, H. Asset Pricing and the Bid-Ask Spread. J. Financ. Econ. 1986, 17, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, l.; Gurel, E. Price and Volume Effects Associated with Changes in the S&P 500 List: New Evidence for the Existence of Price Pressures. J. Financ. 1986, 41, 815–829. [Google Scholar]

- Hedge, S.; McDermott, J. The Liquidity Effects of Revisions to the S&P 500 Index: An Empirical Analysis. J. Financ. Mark. 2003, 6, 413–459. [Google Scholar]

- Bendel, R.; Afifi, A. Comparison of Stopping Rules in Forward “Stepwise” Regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1977, 72, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

| Year | DJSI World | DJSI Asia-Pacific | DJSI Korea | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | Exclusion | N | Inclusion | Exclusion | N | Inclusion | Exclusion | N | |

| 2009 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 13 | - | 13 | 41 | - | 41 |

| 2010 | 8 | 0 | 14 | 16 | 1 | 28 | 10 | 2 | 49 |

| 2011 | 2 | 0 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 30 | 9 | 6 | 52 |

| 2012 | 4 | 1 | 19 | 3 | 0 | 33 | 3 | 3 | 52 |

| 2013 | 4 | 0 | 23 | 8 | 1 | 40 | 5 | 4 | 53 |

| 2014 | 2 | 3 | 22 | 3 | 2 | 41 | 6 | 5 | 54 |

| 2015 | 1 | 2 | 21 | 3 | 3 | 41 | 6 | 8 | 52 |

| 2016 | 5 | 5 | 21 | 2 | 5 | 38 | 2 | 9 | 45 |

| 2017 | 3 | 1 | 23 | 2 | 1 | 39 | 6 | 6 | 45 |

| 2018 | 2 | 5 | 20 | 0 | 4 | 35 | 2 | 8 | 39 |

| Index | N | Mean | SD | Max. | Min. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

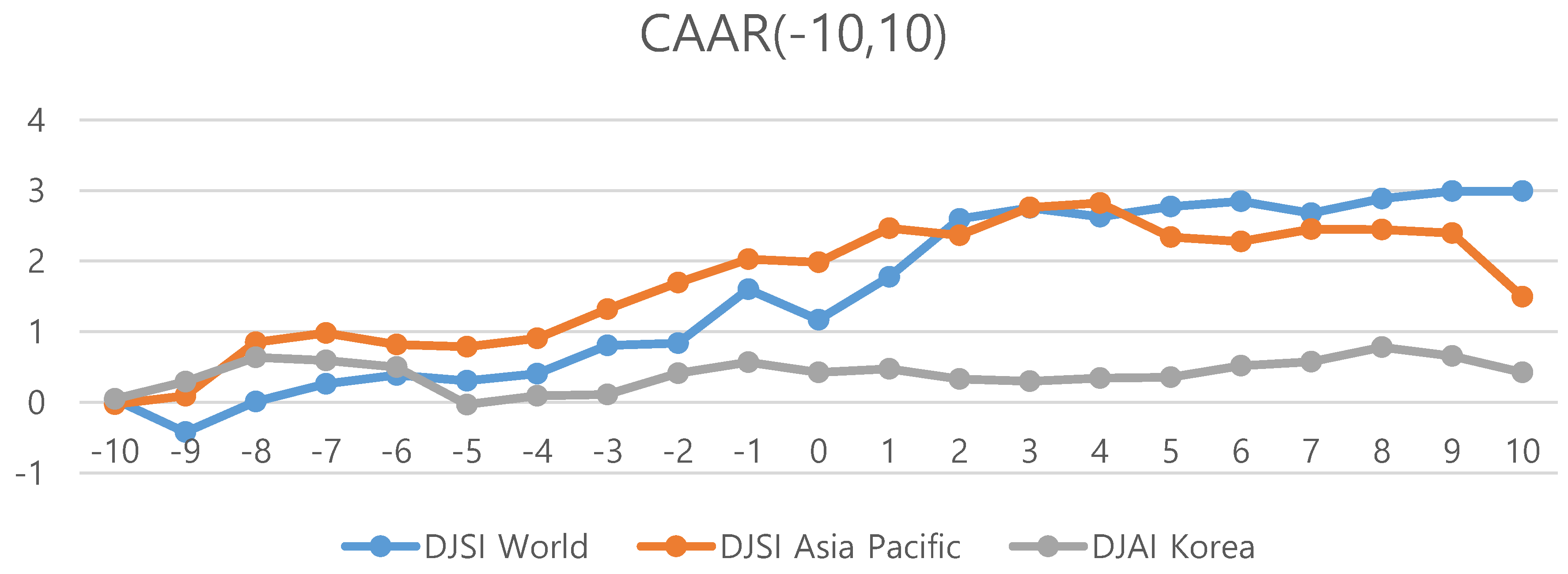

| Panel A: CAAR (−10,10) | |||||

| DJSI World | 33 | 2.9901 (1.83) * | 9.3735 | 31.9517 | −15.0899 |

| DJSI Asia Pacific | 52 | 1.4951 (1.12) | 9.6534 | 20.5259 | −24.3613 |

| DJSI Korea | 85 | 0.4259 (0.38) | 10.2011 | 38.7370 | −21.1914 |

| Panel B: CAAR (−4,3) | |||||

| DJSI World | 33 | 2.2944 (2.66) ** | 4.9613 | 14.1051 | −5.3946 |

| DJSI Asia Pacific | 52 | 1.9735 (2.44) ** | 5.8305 | 14.2862 | −13.0974 |

| DJSI Korea | 85 | 0.3280 (0.47) | 6.3334 | 22.4571 | −30.6823 |

| Index | Event Window | SD | F-Statistic | AAV | t-Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DJSI World | AD −4~−1 | 2.0721 | 1.13 | 0.9653 | 0.18 |

| AD 0~+3 | 2.2034 | 0.9520 | |||

| DJSI Asia Pacific | AD −4~−1 | 2.6254 | 1.07 | 1.0496 | −1.28 |

| AD 0~+3 | 2.7195 | 1.1434 | |||

| DJSI Korea | AD −4~−1 | 2.4863 | 1.11 | 1.0365 | 0.92 |

| AD 0~+3 | 2.3559 | 0.9873 |

| Index | Variable | N | Mean | SD | MAX | MIN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DJSI World | NBR_Indi | 33 | −0.1139 | 0.2047 | 0.2194 | −0.5683 |

| NBR_Fore | 33 | 0.0191 | 0.2052 | 0.5560 | −0.2970 | |

| NBR_ | 33 | 0.1201 | 0.4733 | DJSI World | −0.8600 | |

| NBR_ | 33 | 0.0408 | 0.2298 | 0.7645 | −0.2959 | |

| DJSI Asia Pacific | NBR_Indi | 52 | −0.0766 | 0.1772 | 0.3142 | −0.5104 |

| NBR_Fore | 52 | 0.0403 | 0.2329 | 0.5560 | −0.4709 | |

| NBR_ | 52 | 0.0644 | 0.4697 | 0.8889 | −0.8600 | |

| NBR_ | 52 | −0.0029 | 0.2064 | 0.4471 | −0.5351 | |

| DJSI Korea | NBR_Indi | 85 | −0.0336 | 0.1597 | 0.4349 | −0.4257 |

| NBR_Fore | 85 | −0.0041 | 0.2493 | 0.7343 | −0.6529 | |

| NBR_ | 85 | 0.0287 | 0.5344 | 0.9735 | −1.0000 | |

| NBR_ | 85 | 0.0383 | 0.2523 | 0.7902 | −0.6089 |

| Variable | DJSI World | DJSI Asia Pacific | DJSI Korea |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAR | CAR | CAR | |

| CAR | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| NBR_Indi | −0.3076 * | −0.4408 *** | −0.5349 *** |

| NBR_Fore | 0.0197 | −0.0389 | 0.0725 |

| NBR_ | 0.2812 | 0.3288 ** | 0.3551 *** |

| NBR_ | 0.0725 | 0.3762 *** | 0.3740 *** |

| Index | Intercept | NBR_Indi | NBR_Fore | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DJSI World | 1.88387 (2.00) ** | 1.90202 (0.38) | 2.90873 (1.46) | 1.76236 (0.33) | 0.085 | |

| DJSI Asia Pacific | 0.69979 (0.48) | 7.24192 (0.92) | 4.10831 (1.03) | 0.0284 | ||

| DJSI Korea | 0.32169 (0.49) | 3.55605 (1.34) | 4.48647 (3.59) *** | 0.1452 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Kim, I.; Hong, C.-h. Who Values Corporate Social Responsibility in the Korean Stock Market? Sustainability 2019, 11, 5924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215924

Lee S, Kim I, Hong C-h. Who Values Corporate Social Responsibility in the Korean Stock Market? Sustainability. 2019; 11(21):5924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215924

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Sangki, Insu Kim, and Chung-hun Hong. 2019. "Who Values Corporate Social Responsibility in the Korean Stock Market?" Sustainability 11, no. 21: 5924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215924

APA StyleLee, S., Kim, I., & Hong, C.-h. (2019). Who Values Corporate Social Responsibility in the Korean Stock Market? Sustainability, 11(21), 5924. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215924