Abstract

This paper examines the moral reasoning trends of CEOs (chief executive officers) in the automotive industry, gauging their relations to ethical behaviors and scandals as well as analyzing the influence of scandals and other factors on their moral reasoning. For such a purpose, we carried out a moral reasoning categorization for the top 15 automotive companies in vehicle production in 2017 by applying Weber’s method to letters written by CEOs for the period 2013–2018. A positive global trend was observed, with some CEOs reaching high levels, although the evolution was uneven without clear patterns and, in the light of facts, not sufficient, at least in the short term. We also found evidence linking the moral reasoning stages with the ethical performance of companies and introduced the concept “tone ‘into’ the top”, reflecting how CEO moral reasoning can be shaped by the company and external factors. This paper stresses the importance of considering the moral tone at the top in relation to company ethical behaviors and the interest of education in business ethics. The outcome is useful for CEOs and other managers seeking to improve corporate social responsibility (CSR) and company ethical performance and to anticipate conflicts as well as to leverage for future research.

1. Introduction

The power and influence of CEOs (Chief Executive Officers) have grown in recent decades, in some cases contributing to the collapse of companies and to the financial crisis. Thus, the moral integrity of CEOs is under constant scrutiny [1]. The moral obligation that business has to society is stressed by corporate social responsibility (CSR) [2], while corporate social responsibility is strongly influenced by top-level managers [3].

Treviño and Brown [4] defined the role of a leader as that of a moral manager whose proactive efforts may both positively and negatively influence the behaviors of their followers. Along the same vein, Trevino et al. [5] related the effectiveness of ethical management with the communication of the importance of ethical standards. In all, Weber concluded that there is an expanded view of moral leadership: “leaders must be individuals of moral character, as well as people-oriented leaders who communicate the importance of good values to the firm” [6] (p. 168).

The automotive industry is striving to be more sustainable [7,8,9]. It is one of the most globalized sectors in the world with a highly dynamic market, increasing competition, and huge price and cost pressure. It is immersed at a crossroads with a deep transformational challenge towards cleaner energies ahead with new forms of mobility lurking and society being more and more aware of its side effects. It must become vigilant and demanding with tightened up regulations to fight global climate change.

Recent scandals in the automotive industry have redoubled the interest in this sector. In 2014, authorities began to report discrepancies in emission tests, starting with the Volkswagen Group (VW) [10], who were using a defeat device in diesel engines to cheat emission tests. They pleaded guilty and were condemned to pay a high fine, and the CEO and other former executives were sentenced to prison. Meanwhile, other main players, such as FCA, PSA, Nissan, Renault, Daimler, Ford, and Suzuki, have been caught, or suspected of, carrying out similar practices. Along the same vein, three of the main German car manufacturing groups (Daimler, BMW, and VW) are being accused of a rollout of emission cleaning technology, and the Renault and Nissan’s CEO for the last years is facing problems with justice at present. Indeed, most of the top car manufacturers have been related, in one way or another, to unethical practices, especially over the last five years.

The related body of literature provides evidence of the influence of CEO discourse and moral reasoning on CSR and overall company ethical values, which may be decisive in the avoidance of questionable practices and scandals affecting sectors such as the automotive industry. However, there is a scarcity of research focused on the assessment of CEO moral reasoning in their discourse in such sectors. This paper aims to fill this gap. Through the analysis of letters written by CEOs in annual and sustainability reports, our research strives to attain a diagnosis of the moral reasoning of CEOs leading the main automotive firms over the last years, as well as the extent to which the moral reasoning of CEOs is evolving and redressing, the diversity of such evolution depending on different factors, the relationship between moral reasoning and ethical behavior and scandals, and the degree to which scandals and other issues influence and shape the discourse of CEOs. In connection to this, we introduce a new concept—”tone ‘into’ the top”. For such purposes, several hypotheses are established and tested. We also provide clues to enhance the performance of top managers and open new lines of research.

This paper is structured as follows: After this introduction, Section 2 provides a review of the relevant literature and develops the research hypothesis. Section 3 explains the data and methodology applied in our research. Section 4 presents the results and discussion. Finally, conclusions are shown in Section 5.

2. Literature Discussion

2.1. The Role and Influence of CEOs

The literature emphasizes the role and influence of CEOs from different perspectives in terms of an organization’s core values and decision-making processes, stakeholders and society, CSR policies, etc. The CEO is the most important leader of a company as they play a central role in top management [11]. Senior management has the potential to create mental settings in their organization by embedding their beliefs, values, and assumptions in their organizational culture, and CEOs have gained power and influence over the years [1]. Schein [12] stated that leaders play a key role in shaping and controlling organizational culture. Leader behavior influences the ethical culture of an organization [13,14,15]. Leaders represent relevant role models and guides for their followers [4], and followers tend to imitate their leaders, whether their influence is good or bad [16,17,18]. Leader’s ethics shape their workplace decision-making processes [19,20,21].

The influence of CEOs is not just circumscribed to their organization. They are exposed to the stakeholders and society in general, and they fulfill a promotional function for the company [22]. Apart from their obvious role in transmitting the image of an economically successful company, the need to present their companies as socially responsible has increasingly grown in the last decades. The impulse from top to bottom and sustainability communication are two of the key success factors identified by Colsman [23] on the implementation of a corporate sustainability program. CSR has become a strategic tool for CEOs [24]. CSR is strongly influenced by top-level managers [3], while the CSR engagement of companies positively influences stakeholders’ attitudes and behavioral intentions as well as their corporate image and reputation [25]. Socially responsible organizations are perceived as ethical [26]. Dennis et al. [27] stated that CEOs engage in philanthropy because they want to obtain legitimacy from influential stakeholders and make society a better place. Moreover, Connor [28] showed the importance of leaders in a company in the process of gaining, maintaining, and rebuilding trust, while Wang and Wanjek [29] explained the managerial implications of handling the post-crisis reputation of the Volkswagen emissions scandal. In some cases, CEOs may also promote greenwashing practices that are not necessarily successful in achieving their purpose [30]. Hence, the literature has widely recognized CEOs’ strong leverage over their own organizations, stakeholders, and society.

2.2. Moral Reasoning of CEOs

2.2.1. The Concept and Its Implications

Cunningham [31] defined the tone at the top as the shared set of values in an organization emanating from the most senior executives, which creates an unwritten cultural code. Mahadeo [32] describes tone at the top as “the ethical (or unethical) atmosphere created in the workplace by the leadership of an organization”. Amernic et al. [1] highlight that tone at the top offers clues on how CEOs project themselves to stakeholders. The concept “tone at the top” will be sometimes addressed in this paper as the “moral tone at the top” to reinforce the aspect of morality or ethics upon its definition.

The importance and usefulness of assessing the moral tone at the top is broadly reflected in the literature. It has a critical influence on the work environment, integrity, values, moral principles, and competence of employees [1,33]. Cheng et al. [34] concluded that a leader’s ethics influence their behaviors. Research such as that by Avolio and Gardner [35] or Brown and Trevino [36] proposes that an ethical leader’s behavior brings a positive outcome to a CEOs’ performance.

Thoms [37] concluded that ethical integrity in leadership is directly linked to the organizational moral structure and found a correlation between highly ethical management and business success. Along the same vein, Johnson [38] found that ethical leadership improves organizational performance and profitability. Shin et al. [39] and de Luque et al. [40] showed evidence that ethical leadership enhances organizational performance. Tourish et al. [41] suggested that the tone at the top could be one of the key factors in leadership’s contribution to a company’s success. D’Aquila and Bean [42] provided evidence on how leaders are able to foster ethical decisions or, on the contrary, to encourage unethical responses.

Several studies link CEO ethical leadership to the ethical climate and cultural enhancement [43,44], and even to the improvement of a firm’s performance under the conditions of a strong corporate ethics program [45]. Moreover, Akker et al. [46] (p. 116) established that “the more leaders act in ways followers feel is the appropriate ethical leader behavior, the more that leader will be.” In addition, Spraggon and Bodolica [47] offered, through their research on relational governance and emotional self-regulation, an interesting explanation of how moral reasoning may shape governance mechanisms and help to better understand the decision-making process. The assessment of the moral reasoning of CEOs is a direct tool to assess the tone at the top, to the point that it is often used indistinctively in literature [6].

In all, Staicu et al. [48] (p. 81) concluded that the “tone at the top describes and influences the general business climate within and organization via ethical or non-ethical decision making performed by the top, and determines to some extent, in turn, the ethical behavior of all the people forming that organization”. They also inferred that the culture and behavior in an organization can be shaped by setting the proper tone at the top in order to steer employees in the same and proper direction, and they exposed evidence of how a poor tone or moral failure at the top may have a decisive influence on the crisis and collapse of companies, the latter also supported by Arjoon [49] and Argandoña [50].

In order to emphasize the transfer of values into the organization and the environment by the tone at the top, some authors have coined the term “tone ‘from’ the top” [48,51]. Therefore, the moral tone at the top or the moral reasoning of CEOs is of particular interest, especially in terms of its practical implications, as a shaper of values and behaviors across an organization, as a tool to predict moral behaviors leading to right or wrong decision-making, and ultimately, as a key factor in a company’s success or failure.

An assessment of the moral tone at the top and understanding its implications may help CEOs to consider engaging in programs to enhance their moral reasoning levels. Weber [52] highlighted the importance of ethical education training for such a purpose. Further studies provided conclusively beneficial results for students, even following short programs [53,54].

The moral tone at the top gains even more relevance when a company’s performance is contested. People become more aware of ethical concerns when scandals emerge, and these put the company’s reputation at serious risk [55]. Beelitz and Merkl-Davies [56] examined the use of CEO discourse to restore legitimacy after a nuclear power plant incident. Amernic et al. [1] linked the major crises of companies to a dysfunctional tone at the top. Greenwashing practice is a clear exponent of the dysfunctional tone at the top. This may negatively influence the whole organization to engage in unethical practices. Recent scandals in the automotive sector, as a clear consequence of unethical behaviors, bring ethical concerns into even more focus and strengthen the interest in assessing the moral tone at the top, particularly in this sector.

2.2.2. Assessing the Moral Reasoning of CEOs: Weber’s Method

Different methodologies have been developed in the literature to assess the moral reasoning of CEOs. For our research, we apply the method proposed by Weber [57], who adapted the Kohlberg’s stages of moral development theory to the business organization context to enhance the predictability of managerial ethical behaviors.

Kohlberg’s is one of the leading theories in the cognitive moral development field. Pettifor et al. [58] defined moral reasoning or moral judgment as the ways in which individuals define whether a course of action is morally right, such as by their evaluating different venues of action and taking into account ethical principles when defining their position about an ethical issue.

Moral reasoning is positively related to moral behaviors [59,60,61], which is necessary for moral decision-making [62]. Kohlberg’s theory aims to explain the human reasoning processes and how individuals tend to evolve to become more advanced in their moral judgments. He considers moral reasoning as a major element of moral or ethical behaviors. Kohlberg’s theory, originally conceived by the psychologist Jean Piaget [63] and further developed and enhanced by Lawrence Kohlberg along with his associates [64,65,66,67], holds that moral reasoning has six identifiable development stages, each more adequate at responding to moral dilemmas than its predecessor. This stage model defines these stages as being grouped into three levels of morality: pre-conventional, conventional, and post-conventional. Each level contains two stages, with the second level of each stage representing a more advanced and organized form of reasoning than the first stage at that level. An overview of this model is described herein:

- (a)

- Pre-conventional level: Individuals show an egocentric orientation toward satisfying personal needs, ignoring the consequences that this might entail to others. Their obedience to the norms (laws and regulations) established by the authority is basically motivated by punishment (stage 1) or by the reward or exchange of favorable criteria (stage 2).

- (b)

- Conventional level: Individuals adhere to commonly held societal conventions, contributing to the system’s maintenance and the preservation of social order. More attention is paid to achieving interpersonal harmony and improving relationships, creating a consensus-based culture in the workplace, living up to the expectations of the group, and fulfilling mutually agreed obligations [67,68]. In comparison to the pre-conventional level, individuals move from selfish to concerned with others’ approach [69]. Stage 3 is based on other people’s approval circumscribed to a workgroup, friend circle, etc., where the main motivation is fear of authority and social condemnation. Stage 4 is extended to actions evaluated in terms of laws and social conventions. Compliance with society and not only the closest group gains relevance.

- (c)

- Post-conventional (principled) level: Individuals make judgments about right and wrong based on their principles. Although these are not shared by the majority, moral autonomy is achieved. At stage 5 of the principled level, also known as the “ethics of social contract”, the behavior of an individual is determined with respect to individual rights, and laws are seen as flexible tools for improving human purposes. Exceptions to certain rules are possible provided those rules are not consistent with ones’ personal values or with individual rights and majority interests or considered to be against the common good or well-being of society. Laws or rules that are not consistent with the common good are considered morally bad and should be changed. Individuals at this stage pursue “as much good for as many people as possible”, which is achieved by the majority. Stage 6, named the universal ethical principle orientation, is identified as the highest state of functioning and features abstract reasoning and ethical principle universality. The perspective not only of the majority but of every person or group potentially affected by a decision is considered.

Kohlberg’s stages of moral development theory have been questioned and criticized by different researchers [70,71,72,73], criticism that, in some cases, helped Kohlberg and other researchers shape and improve the theory [67]. Furthermore, McCauley et al. [74] and Peterson and Seligman [75] brought up arguments in favor of this model, relating the impact of leaders’ moral development with their managerial performance. Moreover, it could be argued that moral reasoning might not necessarily lead to moral behaviors. However, a correlation was found between how someone scores on the scale and what their moral behavior is like, this being more responsible, consistent, and predictable from people at higher levels [76]. In fact, many authors have based their research on Kohlberg’s theory in recent years for different purposes, among them, Kipper [77], Doyle et al. [78], Morilly [79], Weber [6], Hoover [80], Frankling [81], Daniels [82], Lin and Ho [83], Galla [84], Hyppolite [85], and Chavez [86].

Moreover, literature relates moral reasoning to leadership performance. Turner et al. [87] concluded that managers who scored at higher levels of Kohlberg’s moral reasoning scale displayed greater evidence of transformational leadership behaviors. Orth et al. [88] found that leaders tend to improve their ability to carry out emotional self-control as they approach the highest level of moral reasoning, while this emotional self-control is a key ingredient for achieving success [89]. However, as Caniëls et al. [90] highlighted, the different stages of moral reasoning should not be regarded as mutually exclusive, but as cumulative sets of governance tools that develop as a manager moves up the moral reasoning ladder. Furthermore, as Spraggon and Bodolica [47] propose, the moral reasoning level shown by a CEO is indicative of the type of governance mechanisms, while the higher level of manager’s moral reasoning may be complemented by lower levels.

As earlier mentioned, Weber [57] devised an adaptation of Kohlberg’s method to the business organization context. While Kohlberg’s intended to assess the moral reasoning development from childhood to adulthood, Weber empirically tested an adapted method which eliminated the needless aspects that could hinder the achievement of results when applying the method to the measurement of managers’ moral reasoning.

This comprehensive adaptation of an abbreviated scoring guide, presented in the methodology shown in Section 3.2, Table 2 enables a simpler, yet reliable, system that allows the analysis of written content to evaluate and categorize the CEOs’ moral language into one of the moral development stages defined by Kohlberg. Weber did not find a significant difference in the results or reliability when applying this simplified method.

Weber [6] applied this adapted method to measure the moral reasoning level of CEOs in the automotive industry with interesting results that will also be contrasted with ours as part of our research. Kipper [77] also applied this adapted method to a different context with relevant conclusions. In all, we consider this method to be the most appropriate for the purpose and scope of our research.

2.2.3. Moral Reasoning in CEOs’ Letters

The CEO’s letter is the most read section [91,92] and one of the most important parts of a company’s annual report [22,93,94], which is normally included at the beginning of the report. It intends to offer a broad overview of the company’s performance throughout a year, including additional financial, but also non-financial, explanations, interpretations, expectations, and future objectives, with a promotional function by conveying a positive image of the company [22]. It sometimes falls into greenwashing practices [95] and triggers decision-making on investments or funding. To put it simply, a CEO letter aims to inform and to persuade.

Trevino et al. [96] exposed that the notion of a moral manager is based on three concepts: modeling through visible actions, the use of rewards and discipline, and communicating about ethics and values. The CEO’s letter has a relevant role in sustainable communication, which is one of the main success factors in CSR. The related body of literature recognizes the CEO’s letter as a rich source to investigate CSR and the relevance of its rhetoric in communicating their values [6,97,98,99,100,101,102]. CEO discourse is also used to gain legitimacy, credibility, and trust from stakeholders [56,97].

CEO discourse is an attempt at creating shared meanings and cultures [1]. The semantics used by CEOs may reveal important aspects of the CEO’s leadership-through-language [103] and are expected to discuss or underlie the ethical components in the decision-making processes [4]. The CEO’s letter is indeed a valuable tool to assess the mindset, values, and ethical aspects of management [1,6,104,105].

The publication of the CEO’s letter is voluntary, and its structure, information content, or rhetoric is not subject to predetermined rules [102]. Therefore, the moral tone at the top may naturally emerge, bearing in mind the strict scrutiny of financial analysts, shareholders, regulators, and journalists as the main constraints [106], as well as society above all.

Either the CEO actually writes the letter in full or with assistance. It is a written document signed by the CEO. Thus, the CEO takes responsibility for a public and accessible document that is expected yearly by stakeholders [1,6]. The CEO’s letter is, therefore, a valuable source to assess the moral reasoning of CEOs.

2.3. Hypothesis

The CEO’s letter is the most read section of annual reports [91,92,94] and is a means to gain legitimacy, credibility, and trust [97]. A proper tone at the top allows gaining, maintaining, and rebuilding reputation and trust [28]. Thus, we might expect leaders to use this valuable tool for this purpose by showing higher ethical values. Moreover, leaders showing higher ethical values are more prone to represent salient ethical role models for their followers and to attract their attention [107].

Nonetheless, according to Spraggon and Bodolica [47], CEOs cannot stop being individual human beings and members of an organization, so the adoption of higher ethical values does not imply they still keep part of their moral reasoning at lower values (i.e., part of the motivation still being to follow the rules), which are also needed for the governance of the company. Schwartz et al. [108] concluded that ethical and legal obligations (more related to lower ethical levels) are not mutually exclusive but reinforce each other. However, higher levels could be expected to be more predominant as they should be more and more influential on CEOs’ motivations, while lower levels could be expected to be less emphasized or underlying in their discourse. By reaching higher levels of moral reasoning, we argue that CEOs will still keep satisfying their needs as individuals, but this will be more based on the satisfaction in succeeding at offering benefits to society. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

CEOs in the automotive industry tend to show an increasing level of moral reasoning predominance over the years.

According to stakeholder-driven principle, CSR is seen as a response to external pressure and scrutiny from stakeholders [109]. The automotive industry, by its own nature, is subject to above-average exposure to society [6] and to tremendous pressure and scrutiny from society to behave more responsibly and become more sustainable, even more so after recent scandals. When scandals emerge, the reputation of companies is put under risk [55,110,111]. Cagle and Baucus [112] stated that scandals in business tend to improve moral reasoning since individuals feel that they cannot ignore the ethical aspects [113]. Scandals in the globalized sector bring a scenario of “high moral intensity” where moral or ethical considerations gain weight in the decision process [114]. People invest more time and energy in situations of high moral intensity and use more sophisticated moral reasoning [114,115]. The automotive sector, owing to its intrinsic characteristics, can be considered a paradigm of the high moral intensity scenario, even more when scandals or conflicts occur. CEOs could also be expected to show pretentiously higher ethical values and fake commitment to sustainability by adopting greenwashing postulates [95,116]. Hence, the authors expect CEOs in the automotive industry to react and shape their moral reasoning to higher stages with the aim of recovering their reputation and trust from stakeholders. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

When a company is affected by a scandal, its CEO will be more prone to reacting and shaping its message to show a higher level of moral reasoning.

Furthermore, Christensen and Kohls [117] proposed that during a crisis in a company, individuals with a higher level of moral reasoning show greater capacity to make the right ethical decision. Weber [57] predicted that the assessment of moral reasoning of managers could lead to greater predictability of managerial and organizational ethical behaviors. Further research follows the same line [1,33,42,48,118]. Amernic et al. [1] linked major crises of companies to a dysfunctional tone at the top. This takes us to our third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

When a firm is affected by a scandal, it is more likely to be preceded by CEO moral reasoning at lower stages.

Likewise, the institutional theory states that political, educational, and cultural factors influence the CSR approach of companies [119]. Gatti and Seele [98] provided evidence of such influence, but on the other hand, exposed common CSR trends among companies from the same market sector. Paul [120] stated that leading companies are expected to establish practices and norms that other firms might be likely to follow.

Studies indicate that changes are related to adapting to trends, especially in terms of society’s expectations about the behaviors of firms and the evolution of their economic performance [121]. For example, Fehre and Weber [122] found that the CEOs of German-listed companies talked less about CSR, including social issues, in times of crisis.

The automotive market sector, with a growing and persistent globalization scenario, could be expected to find confluent ethical behaviors over the years, in spite of the political, educational, or cultural factors of different countries or continents or even factors related to the CEO’s personality or background. Therefore, our fourth hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

CEOs in the automotive industry are more likely to evolve over the years into a more uniform level of moral reasoning with a lower influence of factors stated by institutional theory.

3. Method

This section presents the data and process followed to test the hypotheses stated in the previous section.

3.1. Data

We analyzed the moral language used in the CEOs’ letters included in the annual sustainability or social responsibility reports from the top 15 automotive companies involved in vehicle production in the world during 2017 (Table 1), which was the most current ranking found at the beginning of the research. The reports are publicly available on their websites, thus available for public review and assessment. The sample provides comprehensive data from companies from America, Europe, and Asia, all of them being global players.

Table 1.

Ranking of companies involved in vehicle production worldwide in 2017.

The time frame criteria were to select the latest available material for each of the chosen companies by using the available annual reports from 2013 to 2018, which included the two years before the last wave of scandals started to unfold. The material that served as a basis for this research consists of 90 letters. It was important to analyze the letters from the same period to ensure they were issued under the same circumstances to be equally comparable. Thus, we were able to compare different companies from the same sector under the same global context.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to collect data from such an extensive period of time and a wide range of companies using the hereunder methodology. On the one hand, by examining a period of several years, we were able to better appraise and modulate the overall tone of each CEO as well as sense any trend or pattern. On the other hand, we counted on the previous research carried out in the same sector by Weber [6], to which we will be able to compare our results and findings and see the evolution in the morality shown by CEOs with an even wider perspective.

In order to consider a CEO’s letter in our study, firstly, it had to be clearly written or dictated by the top management. Secondly, it had to be written in first-person style (using “I”, “our”, “We”…), so letters written merely stating descriptive terms were discarded. No letter had to be discarded due to these constraints. Most letters included a picture of the CEO which further reinforced the idea of them transmitting their own discourse. Table 4 in Section 4.1 compiles a list of letters and the management signing them.

3.2. Analysis Methodology

As discussed in the literature review, we used Kohlberg’s stages of moral development theory [67] further adapted to the business context by Weber [57] as the basis for our research and conducted a deep assessment of selected CEO letters through close reading. We applied an iterative process with a qualitative and interpretive approach based on the cycle’s “individual deep review-joint discussion-joint confirmatory analysis”. The diverse background of the authors granted various perspectives when analyzing the tests and enhanced the interpretive process in comparison to a single approach perspective.

The coding process was carried out in four steps, following the criteria of Weber [6,57] and Krippendorff [123]. Firstly, one author prepared a matrix in which the rows included a list with the sentences that appeared in each CEO’s letter while the columns included a list with the indicators for detecting the stages in those letters (see Table 2). In the second step, the authors signaled the indicators found in each letter in the matrix. In the third step, coincidences and discrepancies in the coding of the researchers were checked. In single sentences where only one stage was evident, the coincidences between researchers accounted for 100%. Even so, these codes were revised again to ensure both reliability and validity, so there was coincidence and it was at the correct stage [123]. However, doubts arose in those sentences in which two or three stages could be characterized and where coincidences were around 75%. For this reason, the last step consisted of re-analyzing these sentences. To do this, sentences were divided into sections and then checked by the three authors to define what stages actually appeared in the narrative. In this way, coincidence in these codes was also achieved, assuring both reliability and validity [123]. Examples of the final coding are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Guidance for stage assessment.

Table 3.

Examples of moral reasoning assessment carried out from CEOs’ (chief executive officers’) letters.

In Table 3, we provide examples of the moral reasoning assessment carried out based on letters with an explanation under each extract:

On the other side, we made an assessment of each letter as a whole with the aim of complementing the first approach. We intended to better identify and screen CEO communicative intentions [124] from the actual message and overall moral tone conveyed. We considered factors such as the degree of repetition or reiteration of certain ideas or messages and the relative weight and emphasis of different contents within the letter and evaluated the extent to which certain argumentation undermined or reinforced other contents. For example, we looked for contradictions between well-sounding slogans or mottos and other contents in the letter.

The last step was to share our separate findings and judgments and discuss them to enrich each other’s views to reach a final consensus on the overall categorization of the stage(s). In the case of divergence found in the interpretation, the plan was to discuss it together with the scoring system taken for reference. In general, the degree of coincidence was complete after discussing and complementing individual views. In any case, through this qualitative approach, we were not looking for an exact figure but for the overall stage(s) identification.

4. Results

In this section, we depict the results of the evaluation of the CEOs’ letters by the company throughout the six years of analysis and discuss relevant aspects found in relation to our research questions.

4.1. Letter Assessment

Most letters from the same company presented a similar structure and even content over the years. It became evident that a template is often used and certain ideas, slogans or mottos are repeated, even when changing the CEO.

In most cases, the CEO issued the letter alone. In other cases, the CEO and chairman issued the letter either separately or together and seldom included directors or members of the Sustainability Board. Only one of the CEOs was a woman (GM), and a couple of women co-signed some letters.

In Table 4, we list the name(s) of the management signing the letters, and the stage categorization result for each letter. We also add notes pointing out the continuity of CEO from 2009 to 2013 and highlighting some relevant confirmed scandals. Other companies, such as GM, PSA, Daimler, or BMW, have been recently questioned, but facts have not been proven or are just starting to be revealed.

Table 4.

Summary of CEOs and other top executives signing the letters with stage categorization and scandals.

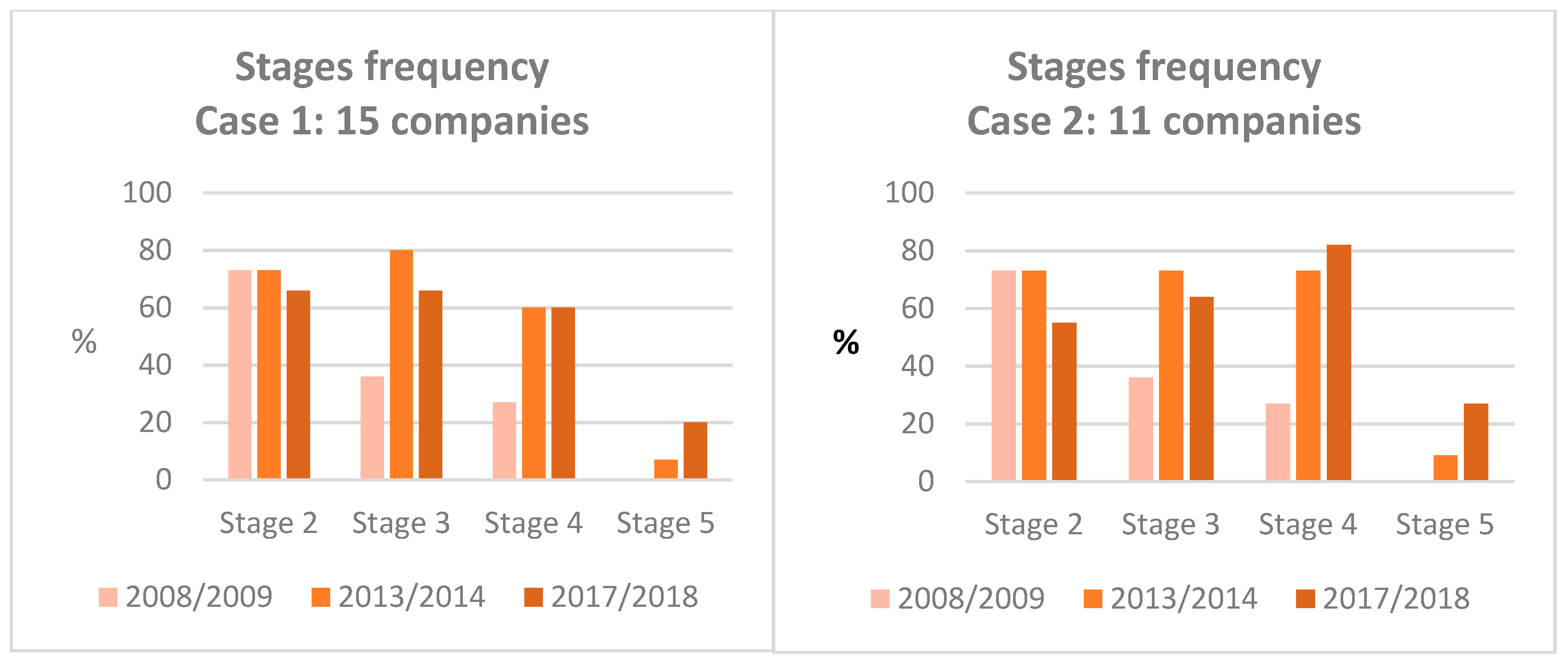

In Table 5, we compile the results of our research in terms of the moral reasoning scoring of CEOs at the beginning and at the end of our period of analysis. For a broader perspective in time, we also include the results obtained by Weber [6], who analyzed the moral reasoning of letters from 2008/2009 using a similar approach. In Figure 1, we represent the frequencies of each stage. We have grouped the results every two years with the aim of reducing the bias related to a particular year:

Table 5.

Moral reasoning scores grouped every two years.

Figure 1.

Frequencies of moral reasoning scores grouped every two years. Case 1, 15 companies from our research. Case 2, 11 companies from Weber’s research [6]. Source. Own source.

4.2. Discussion of Joint Results

4.2.1. Introduction

We observed a good number of changes in CEOs over our period of analysis, some of them as a result of scandals (Volkswagen, Suzuki). During the period 2013–2018, only three companies out of 15 kept the same CEO, whereas six out of the 15 companies kept the same CEO in the period 2009–2013.

During our period of analysis, Nissan was controlled by Renault, and the letters of Renault and Nissan from 2013 to 2016 were addressed by Carlos Ghosn, which offered us a singular opportunity to confront the moral tone shown by the same manager in the two companies. Remarkably, we found a different moral reasoning stage when comparing Nissan with Renault. In spite of the emphasis and reiterations of good intentions in Nissan letters over the years, we found a couple of extracts, one from a 2015 letter and one from 2014 with part of stage 2. In both paragraphs, we were able to identify the nearly hidden motivation of self-interest that was more clearly and consistently evidenced in Renault’s discourses.

Regarding Ford, during the years 2013 and 2014, the CEO and the chairman presented their letters separately, which gave us a good opportunity to compare their moral reasoning under the same context. From 2015 onwards, coinciding with the beginning of scandals, the letters were co-signed by both the CEO and the chairman.

4.2.2. Hypothesis 1

As stated by Spraggon and Bodolica [47], the adoption of higher ethical values does not necessarily imply the absence of lower stages. The consequences of the financial crisis were still latent especially during 2013 with a slight trend to lose impact, which could explain the evolution of stage 2. In any case, we might interpret a trend towards higher stages of moral reasoning. At present, none of the management analyzed showed moral reasoning purely at the pre-conventional level (stage 2), which was the case for nearly 50% of companies in 2008/2009. We can argue that 40% of companies still showed stages not above 2/3 in 2017/2018, but this percentage was above 70% by 2008/2009. If we look at the higher stages, there was a noticeable increase in CEO reasoning at principle level stage 4, especially between 2008/2009 and 2013/2014. Furthermore, in 2013/2014, we started to see some glimpses of stage 5, while in 2017/2018, nearly 30% of companies were consistently showing the post-conventional level of moral reasoning. Thus, in relation to the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

CEOs in the automotive industry tend to show an increasing level of moral reasoning predominance over the years.

While some companies evolved positively (PSA, Toyota, Ford…) and others remained steady (Renault, Saic, Geely…) or even experience some setback (Daimler, Suzuki…), we found, on average, as predicted, a generally positive trend in the sector, progressing towards higher conventional and even postconventional levels, thus contributing to gaining reputation and trust [28]. Therefore, H1 can be confirmed.

From the results, while testing this first hypothesis, we found relevant implications. Taking into account the evidence found in the literature of the positive effects of highly ethical management [37,38,39,40,41], managers could track the evolution of their own moral reasoning scores over time and compare them with those of their competitors as well as become more aware of their transmitted ethical level, also considering their influence on ethical decisions [42] and on building an ethical climate and enhancing their company’s culture [43,44,48].

4.2.3. Hypothesis 2

Moreover, concerning our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

When a company is affected by a scandal, its CEO will be more prone to reacting and shaping its message to show a higher level of moral reasoning.

We found that the context may clearly influence the discourse and moral reasoning of CEOs. Immediately after the Volkswagen scandal, the new CEO eliminated from its discourse any mention of business performance (Stage 2) and showed an increased emphasis and focus on stakeholders, particularly in terms of highlighting the integrity of the firm, trying to keep or regain reputation, intentional greenwashing [95], and seeking customer trust and loyalty (Stage 3). Letters are used intentionally for such purposes, as proposed by de-Miguel-Molina [97] or Connor [28], since after a scandal, the reputation of a company is put at risk [55]. In the case of Suzuki, the subsequent change in chairman also involved some increase in moral reasoning, whereas in the case of Nissan, the moral tone remained at a similar stage, as it did with Renault. Probably the change was not noticeable in the last cases due to the lower repercussions of the issue (Renault) or because the moral tone reasoning was already at a relatively high level (stage 4—Nissan). Thus, we may conclude that H2 tends to be accomplished with a greater or lesser incidence depending on the magnitude of the scandal and the level of moral reasoning prior to the scandal. Through this second hypothesis, we bring new evidence on the reactive role of CEOs in shaping their discourse and showing higher levels of moral reasoning at different degrees depending on the intensity of the scandal with a greater influence when coming from lower scores.

We could also infer that the financial crisis influenced the moral reasoning shown at different periods in time. For example, especially during 2013, with the echoes of the crisis, we found a remarkable emphasis on business performance and economic results, which, in most cases, has lost weight over the years or even disappeared.

4.2.4. Hypothesis 3

In relation to our third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

When a firm is affected by a scandal, it is more likely to be preceded by CEO moral reasoning at lower stages.

At first sight, there was no clear relationship between the moral tone at the top and the appearance of scandals, at least when we looked at the short–immediate term.

When analyzing the three companies with the highest moral reasoning scores (stages 4/5) at present, we only found Toyota to be free of suspicion of unethical practices, whereas PSA’s emission tests were contested during 2017 (facts not proven), and Ford has recently been under investigation for some anomalies in the modeling of emission tests. Thus, higher stages of moral reasoning do not necessarily guarantee or involve ethical behaviors, or at least this is hard to prove under such an approach.

However, when looking with a greater perspective, we can see that Toyota was the only one scoring relatively and consistently high in terms of moral reasoning, both 10 and 5 years ago, whereas Ford and PSA came from lower stages. The same happened with FCA, which had low scores years ago. It could be argued that lower stages of moral reasoning may have an impact on the organization over time, and this footprint may appear or be revealed a while later.

VW’s evidence is more latent. We easily identified consistent lower stages of moral reasoning of the CEO during the years prior to the scandal. During the two immediate years after the scandal, the moral reasoning was mostly focused at stage 3, eliminating self-focus, in order to show integrity and with the will to get the stakeholders’ trust back. Since 2017, the discourse has resumed its focus on business performance while keeping its attention on stakeholders. This is an example of how circumstances may shape the tone at the top. Nonetheless, the moral reasoning of CEOs is a relevant factor that is sure to be assessed along with other elements to predict a crisis or scandal in a company.

We can infer further evidence by looking at the case of a possible rollout of emission cleaning technology affecting the German companies in our research, since we observed that they come from relative low CEO scores over the years.

In all, in line with previous research [1,48,57], we may confirm our third hypothesis, with the additional consideration that the CEO’s moral tone footprint endures over time.

In general, it is clear that the evolution of the moral reasoning of CEOs is not effective or quick enough for the extinction of new scandals looming over previous years and at present.

This third hypothesis confirms a connection between the lower levels of moral reasoning of CEOs and scandals and may help them become more aware of the importance of showing higher ethical values to influence the organization positively, in line with Staicu et al. [48], and to prevent scandals and crises, as predicted by Amernic et al. [1].

4.2.5. Hypothesis 4

Finally, with regard to our fourth Hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

CEOs in the automotive industry are more likely to evolve over the years into a more uniform level of moral reasoning, with less influence of factors stated by institutional theory.

Here the Hypothesis cannot be proven. As shown in Table 5, comparing 2013/2014 vs. 2017/2018, looking at companies individually, we found great gaps in the scores, from 2/3 to 4/5, without clear geographical or cultural patterns that could explain them. There are also significant differences among regions, with China showing consistently lower scores, which continue to the present day. On average, the European and American companies are evolving towards higher levels, while Asian companies remain steady, although this is hard to assess since there are no clear patterns when looking individually at each company.

As per the evidence found, in some cases, a change in CEO involves a clear change of the moral tone at the top (PSA from 2013 to 2014, BMW from 2014 to 2015, FCA from 2017 to 2018, Suzuki from 2015 to 2016). In other cases, either the companies themselves are more influential at shaping the discourse of the CEO, or the CEO adapts his discourse to the corporate culture and values of the company. Carlos Gohsn, being the CEO of Nissan and Renault during the period 2013–2016 is the most flagrant case, showing different stages of moral reasoning depending on the company. In addition, companies like Hyundai, Nissan, or Honda presented changes in CEO without noticeable changes in their tones, at least in the short term. In the case of Honda, the moral tone at the top only remained unchanged for two years. Finally, the context (i.e., VW scandal) alters the discourse and the moral reasoning, although in this case, it may be circumstantial, for a limited period of time of two years in the case of VW.

Under this background, it is difficult to foresee a more uniform level of moral reasoning, although, as seen before, there is a certain general trend towards embracing higher stages.

Moreover, we found several examples showing that when letters are co-signed by other members of the top management, the moral reasoning score is higher. The co-signed letter of VW 2013 showed a balanced combination of stages 2 and 3, while one year later, the letter just signed by the same CEO was merely at stage 2. Something similar happened in the case of Suzuki. During the years 2013 to 2015, the letters were co-signed, and the score was at stages 3–4, whereas from 2016 onwards, coinciding with a change in CEO, the letters were found to be at stages 2–3 only. In Suzuki’s case, the mere fact that the new CEO removes other members of the top management from the letter might be indicative of a more individualistic behavior, and so it could also explain the lower level of moral reasoning shown. In the case of Ford, from 2015 onwards, coinciding with the change of its CEO, the letters are co-signed by CEO and chairman, whereas previously they wrote separate letters. Together, moral tone was more assimilated to the one showing a moral tone at higher stages. Again, this could be explained by a less individualistic approach of the CEO and chairman.

In all, the outcome obtained through the testing of our last hypothesis is that, in spite of extended globalization and the trend that leading companies set practices and norms that other firms might follow, noted by Paul [120], factors, such as those stated by the institutional theory, appear to carry relevant weight in terms of the moral reasoning of CEOs, as found by Matten and Moon [119] in relation to the CSR approach of companies.

5. Conclusions

This paper aimed to assess the moral tone reasoning trends of CEOs in the automotive industry by gauging its relation to ethical behaviors and scandals as well as analyzing the influence of scandals and other factors on the CEOs’ moral tone reasoning. For this purpose, we applied Weber’s method to the CEO letters in the annual reports of the top 15 automotive companies in vehicle production in 2017 for the period between 2013 and 2018. After the introduction, we developed an extensive literature review that led us to our research hypothesis and methodology. Then, we carried out an assessment of the moral reasoning stages of each letter and dissected and analyzed the outcomes.

From the results obtained, we may infer several relevant conclusions and findings. The first one is that, at present, most top automotive company CEOs are operating at the conventional level of moral reasoning, with some of them getting closer to the desirable post-conventional reasoning level, although nearly half of them have still not reached stage 4.

Secondly, when compared with the results of Weber [6], we observed a certain trend to attain higher stages of CEO moral reasoning, which should be a positive sign, although this was quite variable depending on the individual companies. Contrary to the results from Weber and Gillespie [125] and Weber [6] that placed most firm managers at stages 2 or 3 only, at present, the percentage of the sample taken has dropped to 40%. If we remove the two Chinese companies from the equation, the results are even more encouraging. Furthermore, the overall positive trend could lead to further positive global feedback, since leading companies, such as the automotive ones, may be expected to establish practices and norms that other firms might be likely to follow [120].

However, the scandals and suspicions globally affecting the automotive sector show that there is still some way to go, and further complementary approaches should be considered when seeking a way to predict the ethical behaviors of companies or foresee potential problems. It appears evident that the rise in moral tone apparently shown in the letters of CEOs has not resulted in higher ethical behavior in some cases, at least in the short term.

Moreover, as a third important conclusion, we noticed that the moral reasoning shown is not exclusively inherent to the CEO in question but is also influenced by the context (company values, scandals, external pressures, economic situation, etc.), and CEOs may intentionally modulate their discourse and moral reasoning, in line with Hyland [22], i.e., through greenwashing intention [95]. In addition, we found several cases that led us to think about a positive correlation between higher or lower stages of moral reasoning and a higher or lower ethical performance of the company, as predicted in our literature review, especially when adopting a broader perspective in time and not just the short term. It is reasonable to presume that any bad behaviors revealed at present may be the consequence of inappropriate ethical behaviors a while ago. Thus, it is important to consider a sufficient period of time in this type of analysis.

Last but not least, one of the collateral and significant outcomes of this research is that complementary to the extended convention that CEOs are decisive in influencing the culture and values in a company [1,33,48], the values embedded in a company may also decisively influence the moral tone of CEOs. This is clearly evidenced in the discourse of Carlos Ghosn, who adopted a different tone in his letters depending on the company he was leading (Renault or Nissan). We could also infer this from the cases where a new CEO did not change the discourse, although this process may be progressive and may need a certain period of time for each context, as evidenced in the case of Honda, where a new CEO started to reshape the discourse only after two years.

When we recall the definition of the tone at the top as a shared set of values in an organization emanating from the most senior executives which creates an unwritten cultural code [31], we can add that such a set of values may be deeply rooted in a company in such a way that the CEO may fit more into them rather than permeating the company with their own values. We argue that the moral reasoning of a CEO might be reshaped to a greater or lesser extent depending on different factors, such as management resilience, empathy, power over the board of directors, time in the company or at management, stakeholders’ pressure, etc. It is reasonable to think that there is not a fixed pattern for this interaction, and it will all depend on each context and a confluence of factors.

Following the analogy of “tone ‘from’ the top” [48,51], we coined the concept “tone ‘into’ the top” to reflect how the organizational core values or factors, such as scandals or crises, may modulate the CEO discourse and moral reasoning shown.

These findings, along with the implications of showing a certain stage of moral reasoning or moral tone at the top, may be taken into account by companies in the sector to seek how to enhance their overall performance and as a criterion to anticipate possible conflicts as well as a tool of assessment when appointing a top manager.

With regard to CEOs, the results may be of interest in order for them to become more aware of their moral reasoning and its consequences as a starting point to improve their own performance and message for the benefit of their companies, stakeholders, and society and, also, to consider the possibility to enroll in education programs for ethical level enhancement, the usefulness of which was noted by Weber [52], among others. Research on the existing moral tone at the top and its relevance may also encourage governments and business schools to promote or reinforce education in business ethics. In this direction, Pandey et al. [126] showed how education in mindfulness may have a positive impact on moral reasoning.

Limitations and Future Scope of Research

The qualitative assessment carried out involved unavoidable subjectivity and bias, and this obviously may have had an impact on the results. However, it was considered by the authors to be a fair enough way to identify patterns and trends and to obtain revealing conclusions.

This research was based on the written communication of CEOs and not their performance. Staicu et al. [48] highlighted that it is important for leaders to not only express the values of the company but also to set an example with their own actions. Moreover, there is the possibility that some CEOs might be aware of the importance of presenting themselves to have high moral principles, which could intentionally affect their discourse in their letters. Bryce [127] exposed how a CEO with high knowledge about moral principles may use it for their own interest. We also found some further evidence of this in our research. Future studies could investigate the relationship between CEOs’ moral discourse and crises or conflicts with stakeholders or society over time under different contexts, and we could also propose ways to test their message against their actual performance.

Another opened research avenue is the assessment of how the company and the CEO or top management interact and influence each other to create or reshape a set of values over time, which are the mechanisms and the factors for this process. The conceptual framework developed by Kulkarni and Ramamoorthy [128] may be of great support for this mission.

Finally, this methodology of research could be broadened to a wider range of companies in the sector and a longer time frame and could also be applied to other sectors with similar or different contexts to gather further findings and conclusions.

Author Contributions

B.G.-O. and J.G.-C. conceived the study and carried out the investigation; J.G.-C. was in charge of the formal analysis, resources and original draft; all the authors established the methodology; B.G.-O. and B.d.-M.-M. carried out the review and editing; B.d.-M.-M. led the project administration, and supervised and approved the final version.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers for sharing their valuable and constructive comments to improve this manuscript. We are grateful for the means provided by our Department of Business Organization to ease our research works. Finally, we thank the journal for considering our research for publication and guiding us through the process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amernic, J.; Craig, R.; Tourish, D. Measuring and Assessing Tone at the Top using Annual Report CEO Letters; The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, D.L. Top managers as drivers for corporate social responsibility. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 227–248. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman, D.A.; Siegel, D. Defining the socially responsible leader. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L.K.; Brown, M.; Hartman, L.P. A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Hum. Relat. 2003, 56, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevino, L.K.; Brown, M.E. Managing to be ethical: Debunking five business ethics myths. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2004, 18, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. Assessing the “Tone at the Top”: The moral reasoning of CEOs in the automobile industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukitsch, M.; Engert, S.; Baumgartner, R. The implementation of corporate sustainability in the European automotive industry: An analysis of sustainability reports. Sustainability 2015, 7, 11504–11531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, P. Sustainable business models and the automotive industry: A commentary. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2013, 25, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoycheva, S.; Marchese, D.; Paul, C.; Padoan, S.; Juhmani, A.S.; Linkov, I. Multi-criteria decision analysis framework for sustainable manufacturing in automotive industry. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 187, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.C.; Sharon, E. The Volkswagen emissions scandal and its aftermath. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2019, 38, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasson, A. Exploring the ambiguity of hybrid organisations: A stakeholder approach. Financ. Account. Manage 2009, 25, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. How Can Organisations Learn Faster?: The problem of Entering the Green Room; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kalshoven, K.; Den Hartog, D.N.; De Hoogh, A.H. Ethical leadership and follower helping and courtesy: Moral awareness and empathic concern as moderators. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 62, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, C. Managerial Ethics: A Quantitative Correlational Study of Values and Leadership Styles of Veterinary Managers. Ph.D Thesis, University of Phoenix, Phoenix, UZ, USA, March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, J.N. The relationship of leadership style and CEO values to ethical practices in organisations. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptein, M.; Wempe, J.F.D.B. The Balanced Company: A Theory of Corporate Integrity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lasthuizen, K.M. Leading to Integrity: Empirical Research into the Effects of Leadership on Ethics and Integrity. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Social Sciences, VU University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.H.; Lin, C.Y. The moral judgment relationship between leaders and followers: A comparative study across the Taiwan Strait. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.W.; Wood, C.M.; Zboja, J.J. The dissolution of ethical decision-making in organisations: A comprehensive review and model. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidis, J.; Ibrahim, N.A. The impact of emotional intelligence on the ethical judgment of managers. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kish-Gephart, J.J.; Harrison, D.A.; Treviño, L.K. Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. Persuasion and context: The pragmatics of academic metadiscourse. J. Pragmat. 1998, 30, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colsman, B. Nachhaltigkeitscontrolling. In Nachhaltigkeitscontrolling; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 43–90. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, F.; Seele, P. Shorting Ethos: Exploring the relationship between Aristotle’s Ethos and Reputation Management. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2015, 18, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overall, J. Unethical behavior in organisations: Empirical findings that challenge CSR and egoism theory. Bus. Ethics 2016, 25, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, B.S.; Buchholtz, A.K.; Butts, M.M. The nature of giving: A theory of planned behavior examination of corporate philanthropy. Bus. Soc. 2009, 48, 360–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, M. Toyota Recall: Five Critical Lessons. Available online: http://business-ethics.com/2010/01/31/2123-toyota-recall-five-critical-lessons/ (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Wang, Y.; Wanjek, L. How to fix a lie? The formation of Volkswagen’s post-crisis reputation among the German public. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2018, 21, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.A.; Raman, K.K.; Yin, J. Halo effect or fallen angel effect? Firm value consequences of greenhouse gas emissions and reputation for corporate social responsibility. J. Account. Public Policy 2018, 37, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C. Section 404 compliance and ‘tone at the top’. Financ. Exec. 2005, 21, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadeo, S. How management can prevent fraud by example. Fraud 2006, 12, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma, C.; Wemmenhove, P. Tone at the Top is Vital! A Delphi Study. ISACA J. 2009, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.W.; Chang, S.C.; Kuo, J.H.; Cheung, Y.H. Ethical leadership, work engagement, and voice behavior. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoms, J.C. Ethical integrity in leadership and organisational moral culture. Leadership 2008, 4, 419–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.E. Meeting the Ethical Challenges of Leadership: Casting Light or Shadow; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y.; Sung, S.Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. Top management ethical leadership and firm performance: Mediating role of ethical and procedural justice climate. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luque, M.S.; Washburn, N.T.; Waldman, D.A.; House, R.J. Unrequited profit: How stakeholder and economic values relate to subordinates’ perceptions of leadership and firm performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 2008, 53, 626–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourish, D.; Craig, R.; Amernic, J. Transformational leadership education and agency perspectives in business school pedagogy: A marriage of inconvenience? Brit. J. Manag. 2010, 21, s40–s59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aquila, J.M.; Bean, D.F. Does a tone at the top that fosters ethical decisions impact financial reporting decisions: An experimental analysis. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2003, 2, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. CEO ethical leadership, ethical climate, climate strength, and collective organisational citizenship behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtala, M.; Kangas, M.; Lämsä, A.M.; Feldt, T. Ethical managers in ethical organisations? The leadership-culture connection among Finnish managers. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 2013, 34, 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeiss, S.A.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Fahrbach, C.M. Doing well by doing good? Analyzing the relationship between CEO ethical leadership and firm performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akker, L.; Heres, L.; Lasthuizen, K.; Six, F. Ethical leadership and trust: It’s all about meeting expectations. Int. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2009, 5, 102–122. [Google Scholar]

- Spraggon, M.; Bodolica, V. Trust, authentic pride, and moral reasoning: A unified framework of relational governance and emotional self-regulation. Bus. Ethics 2015, 24, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staicu, A.M.; Tatomir, R.I.; Lincă, A.C. Determinants and Consequences of “Tone at the Top”. IJAME 2018, 2, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Arjoon, S. Virtue theory as a dynamic theory of business. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 28, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argandoña, A. Tres dimensiones éticas de la crisis financiera; Documento de Investigación. DI-944. Cátedra “La Caixa” de Responsabilidad Social de la Empresa y Gobierno Corporativo; IESE Bus. Sch. Univ. Navarra: Pamplona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bandsuch, M.R.; Pate, L.E.; Thies, J. Rebuilding stakeholder trust in business: An examination of principle-centered leadership and organisational transparency in corporate governance. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2008, 113, 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. ‘Managers’ Moral Reasoning: Assessing Their Responses to Three Moral Dilemmas. Hum. Relat. 1990, 43, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, R.; Maddux, C.D.; Cladianos, A.; Richmond, A. Moral reasoning of education students: The effects of direct instruction in moral development theory and participation in moral dilemma discussion. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2010, 112, 621–644. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.A. A novel approach to business ethics training: Improving moral reasoning in just a few weeks. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Madariaga, J.; Rodríguez-Rivera, F. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, corporate reputation, and firms’ market value: Evidence from the automobile industry. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2017, 21, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beelitz, A.; Merkl-Davies, D.M. Using discourse to restore organisational legitimacy: ‘CEO-speak’ after an incident in a German nuclear power plant. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. Adapting Kohlberg to enhance the assessment of managers’ moral reasoning. Bus. Ethics Q. 1991, 1, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettifor, J.L.; Estay, I.; Paquet, S. Preferred strategies for learning ethics in the practice of a discipline. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2002, 43, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L. Development of moral character and moral ideology. Rev. Child Dev. Res. 1964, 1, 381–431. [Google Scholar]

- Rest, J.R. Revised Manual for the Defining Issues Test: An Objective Test of Moral Judgment Development; Minnesota Moral Research Projects: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Trevino, L.K. Moral reasoning and business ethics: Implications for research, education, and management. J. Bus. Ethics 1992, 11, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rest, J.R. The major components of morality. In Morality, Moral Behavior, and Moral Development; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, J. The Moral Judgment of the Child; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg, L. Continuities in childhood and adult moral development revisited. In Life-Span Developmental Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1973; pp. 179–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg, L. Essays on Moral Development; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg, L. The Psychology of Moral Development: Essays on Moral Development; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Colby, A.; Kohlberg, L.; Speicher, B.; Candee, D.; Hewer, A.; Gibbs, J.; Power, C. The Measurement of Moral Judgement: Volume 2, Standard Issue Scoring Manual; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Trevino, L.K. Ethical decision making in organisations: A person-situation interactionist model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; Wasieleski, D. Investigating influences on managers’ moral reasoning: The impact of context and personal and organisational factors. Bus. Soc. 2001, 40, 79–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, C. In a different voice: Women’s conceptions of self and of morality. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1977, 47, 481–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, C. New maps of development: New visions of maturity. Am. J. Orthopsychiatr. 1982, 52, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harkness, S.; Edwards, C.P.; Super, C.M. Social roles and moral reasoning: A case study in a rural African community. Dev. Psychol. 1981, 17, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpendale, J.I. Kohlberg and Piaget on stages and moral reasoning. Dev. Rev. 2000, 20, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, C.D.; Drath, W.H.; Palus, C.J.; O’Connor, P.M.; Baker, B.A. The use of constructive-developmental theory to advance the understanding of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 634–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; Seligman, M.E. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Crain, W. Theories of Development: Concepts and Applications; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kipper, K. A Neo-Kohlbergian approach to moral character: The moral reasoning of Alfred Herrhausen. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017, 8, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, E.; Hughes, J.F.; Summers, B. An empirical analysis of the ethical reasoning of tax practitioners. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morilly, S.W. Ethical leadership: An assessment of the level of moral reasoning of managers in a South African short-term insurance company. Master’s Thesis, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa, November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, K.F. Values and organisational culture perceptions: A study of relationships and antecedents to managerial moral judgment; Bowling Green State University: Bellville, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, R.S. Exploring the Moral Development and Moral Outcomes of Authentic Leaders; ProQuest: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, D.M. Ethical Leadership and Moral Reasoning: An Empirical Investigation; ProQuest: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Ho, Y.-H. Cultural influences on moral reasoning capacities of purchasing managers: A comparison across the Taiwan Strait. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2009, 37, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galla, D. Moral Reasoning of Finance and Accounting Professionals: An Ethical and Cognitive Moral Development Examination. Ph.D. Thesis, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hyppolite, F.A. The Influence of Organisational Culture, Ethical Views and Practices in Local Government: A Cognitive Moral Development Study; ProQuest: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez, J. Morality and Moral Reasoning in the Banking Industry: An Ethical and Cognitive Moral Development Examination. Ph.D. Thesis, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Epitropaki, O.; Butcher, V.; Milner, C. Transformational leadership and moral reasoning. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orth, U.; Robins, R.W.; Soto, C.J. Tracking the trajectory of shame, guilt, and pride across the life span. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 99, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraven, M.; Tice, D.M.; Baumeister, R.F. Self-control as a limited resource: Regulatory depletion patterns. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caniëls, M.C.; Gelderman, C.J.; Vermeulen, N.P. The interplay of governance mechanisms in complex procurement projects. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2012, 18, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuoli, M.; Paradis, C. A model of trust-repair discourse. J. Pragmat. 2014, 74, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppinen, A.; Hänninen, V.; Lähtinen, K. ISO 26000 in the assessment of CSR communication quality: CEO letters and social media in the global pulp and paper industry. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, A.; Grasselli, N.I. Defeating the Minotaur: The construction of CEO charisma on the US stock market. Organ. Stud. 2006, 27, 811–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman Mir, M.; Chatterjee, B.; Shiraz Rahaman, A. Culture and corporate voluntary reporting: A comparative exploration of the chairperson’s report in India and New Zealand. Manag. Audit. J. 2009, 24, 639–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, A.; Vollero, A.; Conte, F.; Amabile, S. “More than words”: Expanding the taxonomy of greenwashing after the Volkswagen scandal. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevino, L.K.; Hartman, L.P.; Brown, M. Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2000, 42, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Miguel-Molina, B.; Chirivella-González, V.; García-Ortega, B. CEO letters: Social license to operate and community involvement in the mining industry. Bus. Ethics 2019, 28, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, L.; Seele, P. CSR through the CEO’s pen. Uwf UmweltWirtschaftsForum 2015, 23, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alstine, J.; Barkemeyer, R. Business and development: Changing discourses in the extractive industries. Resour. Policy 2014, 40, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, H. On the ideological role of employee reporting. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2013, 24, 360–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, M. CEO rhetorical strategies for corporate social responsibility (CSR). Soc. Bus. Rev. 2012, 7, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamson, E.; Amir, E. The information content of the president’s letter to shareholders. J. Bus. Finan. Account. 1996, 23, 1157–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amernic, J.H.; Craig, R. CEO-Speak: The Language of Corporate Leadership; McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Amernic, J.H.; Craig, R.J. Guidelines for CEO-speak: Editing the language of corporate leadership. Strategy Leadersh. 2007, 35, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, R.; Amernic, J. Are there language markers of hubris in CEO letters to shareholders? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Taffler, R.J. The chairman’s statement-a content analysis of discretionary narrative disclosures. Account. Audit Account. 2000, 13, 624–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.; Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Finkelstein, S. Someone to look up to: Executive–follower ethical reasoning and perceptions of ethical leadership. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 660–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.S.; Dunfee, T.W.; Kline, M.J. Tone at the top: An ethics code for directors? J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 58, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ralston, D.A. Corporate social responsibility in Europe and the US: Insights from businesses’ self-presentations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys, A.S.; Cauberghe, V.; Vyncke, P. Restoring reputations in times of crisis: An experimental study of the Situational Crisis Communication Theory and the moderating effects of locus of control. Public Relat. Rev. 2010, 36, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. Protecting organisation reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2007, 10, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagle, J.A.; Baucus, M.S. Case studies of ethics scandals: Effects on ethical perceptions of finance students. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 64, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.D.; Dalal, R.S.; Bonaccio, S. A meta-analytic investigation into the moderating effects of situational strength on the conscientiousness–Performance relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 1077–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M. Ethical decision making by individuals in organisations: An issue-contingent model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 366–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Pauli, K.P. The role of moral intensity in ethical decision making: A review and investigation of moral recognition, evaluation, and intention. Bus. Soc. 2002, 41, 84–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S. The Relationship between Non-financial Reporting, Environmental Strategies and Financial Performance. Empirical Evidence from Milano Stock Exchange. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.L.; Kohls, J. Ethical decision making in times of organisational crisis: A framework for analysis. Bus. Soc. 2003, 42, 328–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, B. The anatomy of corporate fraud: A comparative analysis of high profile American and European corporate scandals. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]