1. Introduction

After more than 30 years of rapid development since reform and opening-up, China’s financial market is at a low ebb under the macro background of the economy being hampered by trade wars and other factors. Inclusive finance, as a new financial concept, was first explicitly proposed by the United Nations in 2005 as a financial system that effectively and comprehensively serves all groups and sectors of society, especially the poor and low-income populations. Inclusive finance plays an important role in regional and individual income growth and national industrial upgrading [

1], solves the problem of financing difficulties for small- and medium-sized enterprises, helps to reduce poverty rates and social inequality [

2], and also vigorously drives financial markets out of a downturn. In order to deepen inclusive financial reform, governments actively support it at the policy level. In 2013, the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China included inclusive finance in the Party’s resolution for the first time. In 2015, the Government Work Report further proposed to vigorously develop inclusive finance. In early 2016, the State Council issued the paper “On Promoting Inclusive Financial Development Planning (2016–2020)”, which promotes inclusive finance as part of the national strategy. The abovementioned policy support indicates the growing importance that China attaches to inclusive finance.

Inclusive financial services are aimed at all sectors of society with financial needs. Since agriculture plays a considerable role China’s national economy, the 2018 Central Document No. 1 states that inclusive finance should focus on rural areas. Rural inclusive finance refers to economic activities that provide financial products and services to everyone at affordable costs based on the principles of equal opportunity and business sustainability. The necessity of developing rural inclusive finance lies in the fact that it is an inevitable requirement for China to build a well-off society in a comprehensive manner, which is conducive to promoting the sustainable and balanced development of the financial industry, promoting public entrepreneurship and innovation, and also promoting social equity and harmony. Developing rural inclusive finance is feasible because the penetration of financial products and services in rural China is low and the scale and structure of consumption lags behind other areas, which indicates that there is broad space for development.

Rural inclusive finance in China has made great progress. Inclusive finance plays a positive role in alleviating financial poverty [

3], promoting urban and rural integration [

4], and increasing farmers’ income [

5]. However, there have also been some obstacles, such as the lack of innovation in the rural financial system [

6], regional development imbalance, imperfect top-level design, lack of financial institutions, lack of targeted financial products and services, lack of financial knowledge, low penetration rate, the serious financial exclusion phenomenon, and the fragile financial ecological environment. These obstacles have led to the slow development of rural inclusive finance [

7]. Scholars have tried to provide solutions for sustainable development from the perspectives of national policy [

8], financial institutions [

9], the financial supply mode [

10], the education level of users [

11], the behavior preferences of users [

12], and so on; however, progress has been limited. This paper argues that the root of such problems lies in the lack of coordination and cooperation among the internal elements. The development of inclusive finance involves the cooperation of multiple sectors and subjects. Especially because of the distinct nature of rural customer groups and the policy orientation of financial products, inclusive finance has a more complex coordination problem than traditional finance. Therefore, based on the new perspective of synergy theory, this paper puts forward the corresponding coordinated countermeasures by segmenting the types of financial institutions and analyzing the cooperative resistance among the subjects in the system.

The contributions of this paper are as follows. Theoretically, this paper innovatively expands the application scenario of synergy theory to research on rural inclusive finance. A systematic consideration of the interaction between the subjects contributes to the sustainable development of rural inclusive finance. Practically, one contribution is the summary of the experience of China’s rural inclusive financial development, which can provide support to other countries that are developing rural inclusive finance. The second contribution is that this work provides a new research perspective for researchers in this field, that is, studying the operation mode and cooperation of the subjects in the system, as well as classifying the financial institutions according to the national political financing tasks and considering the differences in motivation caused by the heterogeneity of financial institutions. The third contribution is that this paper provides guidance for government departments and financial institutions, which is also helpful for rural users to understand and support inclusive finance. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a theoretical review.

Section 3 summarizes the experience of China and describes the current dilemma through vertical and horizontal comparisons.

Section 4 analyzes the cooperative resistance among the subjects from the perspective of synergy theory. Solutions to reduce cooperative resistance are proposed in

Section 5, and

Section 6 discusses the limitations of the article and the plan of further research.

2. Literature Review

Rural inclusive finance is the continuation and deepening of rural finance. Rural financial theory includes the theories of agricultural credit subsidy, rural financial markets, and incomplete competition [

13,

14,

15]. The theory of agricultural credit subsidy is based on the peculiarity of the agriculture industry, which assumes that rural residents have no ability to save, so government agencies are encouraged to inject low-interest-rate funds into rural areas. However, funds from the government not only make rural finance lose its internal vitality, but it also becomes a financial burden. Thus, it is an unsustainable financial mechanism. Actually, rural residents have the desire and ability to save. The theory of rural financial markets emphasizes the importance of the market mechanism, holding that we should tap the endogenous power of rural finance, so as to activate the rural financial market. However, in the case of full marketization, the high cost of financial services and the requirement of collateral will greatly limit the full access of small holders and poor farmers to financial services. The government still needs to intervene to satisfy the financial needs of this group. The theory of incomplete competition was proposed in order to remedy market failure and to find a balance between government intervention and market liberalization to cultivate an efficient financial market. After the development of microcredit and microfinance, inclusive finance has been formally put forward on the basis of the above-discussed theory and practice.

Since then, the academic community has mainly studied inclusive finance from three aspects. First, there is the concept and measurement of inclusive finance. Globally, there are two main evaluation systems for assessing the development level of inclusive finance. One is the evaluation index designed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) from the dimension of formal finance accessibility and utilization. The other is the global inclusive finance core index developed by the World Bank [

16]. Researchers have also measured the level of inclusive financial development [

17,

18,

19] from different dimensions. Second, there are the antecedent variables of inclusive finance, that is, the factors that affect its development and implementation. Research on the antecedent variables is mainly from the perspectives of the main characteristics of financial demand [

20,

21], the characteristics of financial service supply [

22,

23,

24], and the social environment [

25]. Third, there are the consequence variables of inclusive finance, that is, what will be affected and what kind of impact will be produced. Research on inclusive financial consequence variables includes promoting economic growth [

26], improving the efficiency of financial intermediation [

27], remedying the financial exclusion of some groups, and so on [

28].

However, most studies on the antecedent variables of inclusive finance are based on a certain subject dimension or research situation in the financial system, and few studies have focused on the interaction among various elements of the system. In order to build a complete and systematic rural inclusive financial system, it is necessary to change the current state of “fragmentation” and enhance overall effectiveness through “cooperation” among multiple factors. The synergy elements of rural inclusive financial system include three main subjects: government, financial institutions, and users. According to synergy theory, the collaborative behavior of the three subjects determines the efficiency and effectiveness of the system. The operation of financial institutions has always been the focus of such research, while research on other subjects is relatively scarce. Thus, exploration of the “synergy mechanism” is obviously insufficient, which is precisely the biggest obstacle in the process of making finance more inclusive in rural China. It directly affects the cultivation of the driving force to develop inclusive finance in rural areas. This paper holds that cooperation among subjects is conducive to the development of inclusive finance in rural areas.

3. Experience and Dilemma

Inclusive finance in rural China has made impressive progress in recent years. In order to have a clearer understanding at the global level, we made a horizontal international comparative analysis among China and four control groups. The control groups were selected based on a paper called “Inclusive Finance in China from a Global Perspective: Practice, Experience and Challenges” issued by the People’s Bank of China. The four control groups are G-20 high-income countries (G-20 HIC), G-20 middle-income countries (G-20 MIC), large middle-income countries in East Asia and the Pacific (EAP L-MIC), and other large middle-income countries (Other L-MIC). The basic information of the control groups is shown in

Table 1.

3.1. Experience of China

The most prominent achievement of China’s practice lies in the high availability of financial services, which is the core element and driving force, including the full coverage of physical service outlets and the high opening rate of trading accounts. Like other countries, China’s traditional financial service providers used to be limited and geographically uneven. The experience of China can be summarized in three points: First, importance was attached to the construction and development of rural credit cooperatives. Second, an agency service network was established. Third, characteristic bank branches were set up.

3.1.1. Attention to the Reform of Rural Credit Cooperatives

Rural credit cooperatives in China are not only the most widely distributed financial service providers in rural areas but also the key institutions for achieving the goal of inclusive finance. The Chinese government attaches significance to rural credit cooperatives by active policy support and continuous reforms. In 2003, the government deepened the reform of rural credit cooperatives and created two new organizational forms—rural commercial banks and rural cooperative banks—which were transformed into commercially sustainable business models. Since then, rural credit cooperatives have entered their fastest growth period in history. In 2016, the national rural credit cooperatives system achieved a net income of CN¥51.9 billion, a nonperforming loan ratio of 7.3%, a capital adequacy ratio of 8.4%, and agricultural loan balances of CN¥2.7 trillion, as shown in

Table 2.

3.1.2. Agency Service Network

Physical availability is a key element of inclusive finance, which mainly includes the dimensions of branches, ATMs, and agencies. As shown in

Figure 1, the physical availability of China’s financial sector is even higher than the median level of the G-20 high-income countries, mainly due to China’s extensive network of agencies, which is well above the median level of the other control groups. By the end of 2018, there were 865,000 agricultural withdrawal service points nationwide, with a coverage of 98.2% in villages.

3.1.3. Establishment of Characteristic Branches of Commercial Banks

The establishment of characteristic branches makes commercial banks more geographically dispersed and provides professional and convenient financial services to communities as well as small- and micro-sized enterprises. Community branches and small- and micro-sized branches are two types of characteristic branches.

By the end of January 2018, national joint-stock banks had set up 5153 community branches and small- and micro-sized branches. Characteristic branches generally avoid being located in areas where financial services are highly concentrated, such as urban centers, but actively extend to counties, towns, and villages. For example, in Zhejiang Province in south China, about 48% of the established branches are located in townships and 22% in rural areas. The establishment of characteristic branches has effectively shortened the distance to customers, and some urban commercial banks have further expanded the grassroots market by setting up outlets in urban fringe areas and urban villages.

3.2. Dilemma of Inclusive Finance in Rural China

In order to adequately solve the problem, it is necessary to understand the present situation. As mentioned above, the global inclusive finance core index includes four dimensions: the general development level, obstacles, loan sources, and motivation of savings. The general development level of inclusive finance was selected for this article. The details include the accounts possession rate in formal financial institutions, whether deposits have been made or not in formal financial institutions during the past 12 months, and whether loans were obtained or not from formal financial institutions during the past 12 months, which are referred to below as the formal accounts rate, the formal savings rate, and the formal credit rate, respectively. Using data from the World Bank Global Inclusive Finance Database, we implemented longitudinal and horizontal analyses of inclusive financial development in rural China.

The results of the longitudinal analysis are shown in

Figure 2. During the period from 2011 to 2017, the formal accounts rate was on an upward trend, from 0.580 to 0.777. The formal credit rate increased annually, from 0.069 to 0.089. However, the formal savings rate rose first but then fell, reflecting a decline in the willingness to save.

The results of the horizontal comparison are shown in

Table 3. The formal accounts rate and the formal savings rate show that China is slightly lower than the G20 high-income countries but significantly higher than other control groups. It fully demonstrates that saving in formal financial institutions is still preferred for rural residents in China, which is consistent with the structure of rural financial markets dominated by the Chinese banking system. The data show that only 8.9% of respondents have borrowed from formal financial institutions in the past year, which is lower than other control groups. Comparing the formal savings rate, it is obvious that the pumping effect is still significant in the rural financial system of China.

5. Solutions

5.1. Government and Financial Institutions

The key to reducing the cooperative resistance between the government and financial institutions is to motivate the willingness of financial institutions. According to the previous analysis, financial institutions are reluctant to develop inclusive finance because of the high risks and low returns. Therefore, cooperative resistance can be reduced by policy support from the government as well as the reduction of costs and risks by financial institutions.

5.1.1. Measures for the Government to Motivate Financial Institutions

The government can macro-legislatively protect the rights and interests of financial institutions and the prospect of sustainable development, specifically by considering the following four aspects. Firstly, implement the guiding role of the inclusive finance concept and build a comprehensive and systematic legal guarantee system for the development of inclusive finance in rural areas. Build a legal framework system with “The Promotion of Rural Financial Development Law” as the head and rural commercial financial law, rural policy financial law, rural cooperative financial law, and folk financial law as the branches. Further, construct the basic system considering the three dimensions of the control of inclusive finance development in rural areas, the protection of the financial rights of vulnerable groups in rural areas, and the guarantee of system implementation [

39]. Secondly, carefully analyze the costs and benefits of taxes on inclusive finance and formulate preferential tax policies based on the actual situation to stimulate the development of the inclusive finance business of financial institutions. For example, the interest income of small loans can be exempted from VAT, the loan reserve for agriculture-related and small- and medium-sized enterprises can be deducted before tax for enterprise income tax, and the loan contracts signed by financial institutions and small- and micro-sized enterprises can be exempted from stamp duty [

40]. Thirdly, provide appropriate fiscal subsidies, but be aware of the nonindependence of financial institutions due to excessive subsidies. Fourthly, strengthen infrastructure construction. For example, strengthen the construction of transportation facilities to reduce high transaction costs. Strengthen the construction of communication facilities to reduce information asymmetry and provide a path for sustainable development.

5.1.2. Measures for Financial Institutions to Increase Motivation

The development of inclusive finance by financial institutions can be carried out from the perspective of reducing costs and risks. With the advent of the era of big data, the importance of digital inclusive finance is becoming increasingly prominent. The development of digital inclusive finance, which is the way to make inclusive finance sustainable, has become the consensus of all countries worldwide. Financial institutions can reduce costs by developing digital inclusive finance, while risk reduction can be combined with big data by updating loan model to reduce the rate of nonperforming loans.

Firstly, from the perspective of cost reduction, financial institutions should follow the trend of the big data era and actively develop digital inclusive finance. Digital inclusive finance breaks the time and location limitations of financial services [

41], decreases transaction costs [

42], and effectively alleviates the problem of information asymmetry [

43]. Further, it improves the credit environment in poor rural areas and broadens the channels of investing and financing in such places, which guarantees the sustainable development of inclusive finance and also makes it possible to combine the profit-making goals of financial institutions and the social objectives of the government.

Presently, China’s digital inclusive finance is developing soundly and has broad room for expansion. For this article, the data of rural areas in the Global Findex 2017 database were selected, which shows the development of digital inclusive finance in China’s rural areas compared to the previously mentioned matched groups and the indicator of digital payment. As shown in

Figure 4, among Chinese rural residents over 15 years old, 33% have received digital payments while 56% have used digital payments in the past year. In addition, 34% of the respondents said they had paid their bills on the Internet in the past year, while 41% had shopped on the Internet in the past year. These data show that China, in terms of digital payments, far outperforms the G20 middle-income countries, the big middle-income countries in East Asia and the Pacific, and other big middle-income countries. However, China is still lagging behind the G20 high-income countries, which demonstrates that there is room for development of digital inclusive finance.

Secondly, from the perspective of risk reduction, financial institutions should improve the flexibility of mortgage borrowing. To be specific, there are two points. First, adjust the existing service mechanism, eliminating the dependence on collateral and adapting the credit loan model to farmers. Second, by means of fintech tools, build up the credit big data of farmers to allow the timely tracking of credit status, which will reduce the cost of obtaining farmers’ information and identifying their risk, as well as reduce the possibility of non-performing loans.

5.2. Financial Institutions and Users

The key to reducing synergy resistance between financial institutions and users is to match supply and demand. The mismatch between supply and demand is reflected in the following two aspects. First, users with demand for financial services are still excluded from existing financial services and products. Second, financial services and products are limited in terms of quantity and variety. Reducing the imbalance between supply and demand should start with supply-side reform. Financial institutions should start by increasing the quantity and improving the quality of the supply, while users increasing the use of online financial instruments and strengthening credit construction.

5.2.1. Measures for Financial Institutions to Provide Sufficient Supply

From the perspective of increasing the quantity of the supply, financial institutions should reasonably develop service networks in rural areas, fill the gap of financial services, and accurately focus on users who genuinely lack access to financial services to provide inclusive financial services. This mainly starts with increasing the accessibility of inclusive finance services by accelerating the construction of physical service networks offline, such as increasing the number of ATM and POS machines and branches. In order to visually demonstrate the impact of financial services availability on the financial needs of rural users, this paper uses Matlab software to carry out numerical simulations about the impact of POS and ATM supply on the loans of “agriculture, rural areas, and farmers”.

Figure 5a–c are the results of the POS machines amounting to the agricultural loan balance, the rural (county and sub-county) loan balance, and the farmer’s loan balance;

Figure 6a–c are the results of ATM machines amount to the agricultural loan balance, rural (county and sub-county) loan balance and the farmer’s loan balance. The horizontal x-axis in the figure is the number of ATM or POS machines per 10,000 persons in rural areas and the unit of the vertical Y-axis is trillion yuan. The data is from 2015 to 2018, and the data source is the official website of the People’s Bank of China and the China Financial Yearbook.

Table 4 is the equation coefficients generated during numerical simulations. The optimal fit function is a linear function, where P1 represents the slope and P2 is the constant term. R-square represents the explanatory power of the model fitting. It can be seen that the three models in

Figure 5a–c have a strong explanatory power, and the explanatory powers of the three models in

Figure 6a–c are acceptable. The slope coefficients of the six models are all positive, indicating that increasement of POS machines and ATM machines is indeed beneficial to increase financial availability in rural areas.

From the perspective of increasing the quality of the supply, financial institutions should conduct thorough client surveys, discern the real financing service needs in rural areas, and provide a targeted launch of inclusive financial products tailored to consumer needs. On the one hand, professionals can be hired to design appropriate inclusive financial products so as to integrate users’ needs and to adapt to the seasonal and nonrecurrent financial needs of users in rural areas. On the other hand, fintech tools can be used to develop more user-friendly digital inclusive financial products in rural areas to meet the diversified financial needs.

Additionally, according to the features of the new types of agricultural business entities, financial institutions can be rooted in industry planning in poor areas and implement the strategy of “One County, One Industry, One Village, One Product”, focusing on developing and designing financial products for the ecological aquaculture industry, economic forest and wood industry, leisure tourism, agro-products processing industry, and folk tourism. They can develop a new industrial chain financing model of “enterprise and peasant household”, “leading enterprises and peasant household”, and “professional cooperatives and peasant household” and continuously improve the penetration and suitability of financial services.

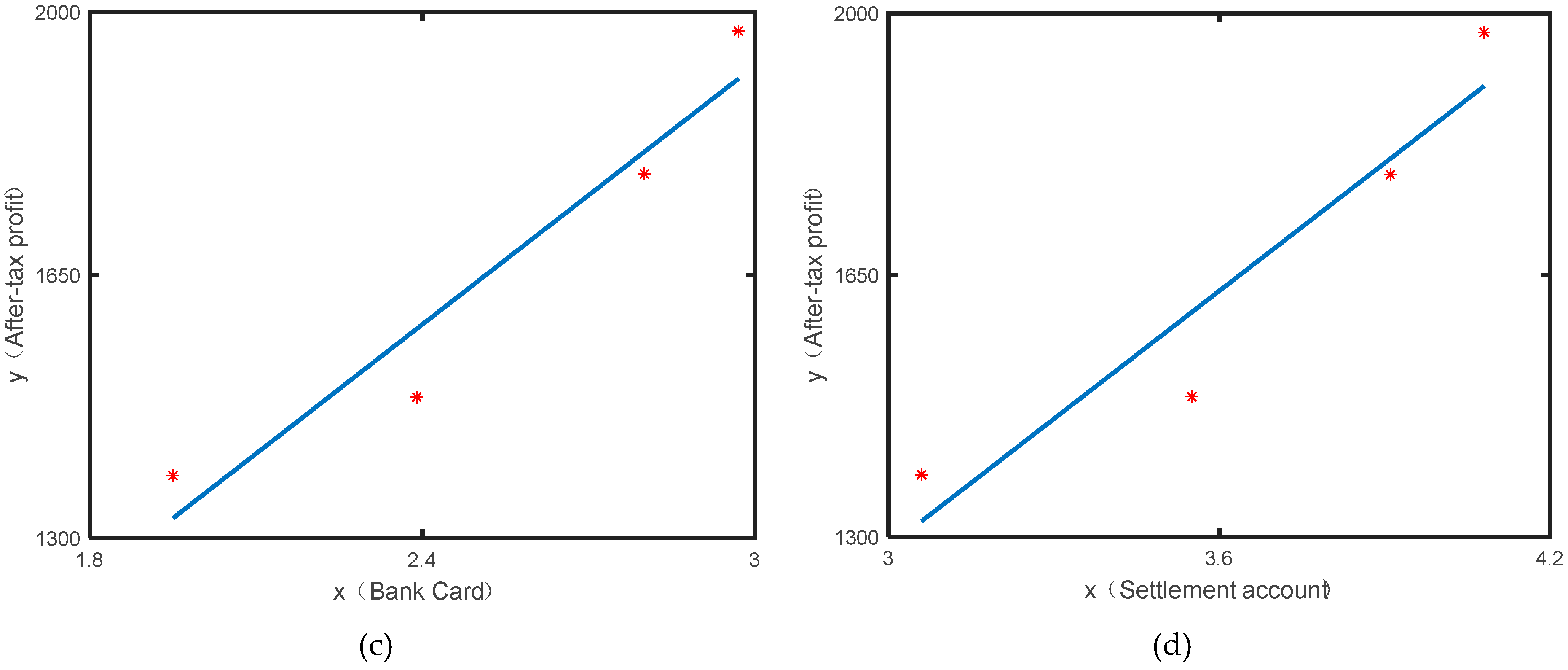

5.2.2. Measures for Users to Make Use of the Supply

The use of online financial instruments such as bank accounts and bank cards, as well as the use of online financial tools such as the Internet and mobile phones, is helpful to expand access to financial services and meet their financial needs. It will also help improve the profitability of financial institutions and enhance the sustainable development of inclusive finance in rural areas. In order to visually show the impact of the use of financial instruments on the profitability of financial institutions, this paper uses Matlab software to carry out numerical simulations. The explanatory variables are the number of mobile banking opened in rural areas (100 million households), the number of online banking opened in rural areas (100 million households), the number of bank cards per person in rural areas, and the number of bank settlement per person in rural areas (household).The interpreted variable is the after-tax profit of rural commercial banks (100 million yuan). The data for

Figure 7a,b is from 2015 to 2017, while for

Figure 7c,d is from 2015 to 2018. The data is from the official website of the People’s Bank of China and Almanac of China’s Finance and Banking.

Table 5 is the equation coefficients generated during numerical Simulation. According to the R-square index, the four models explain well. The slope coefficient is positive, indicating that the use of mobile banking, online banking, bank cards, and personal bank settlement accounts by rural users will help increase the profitability of financial institutions in rural areas.

Credit construction can be done in both active and passive ways. Active credit construction requires users’ own behavioral norms and strengthens self-credit management. The construction of passive credit needs to take the form of supervision, punishment, or moral restraint. The credit problem is mainly caused by information asymmetry. The first solution is to learn from the experience of India [

44] by building a perfect credit system to enhance the availability of formal credit and alleviate the imbalance of financial development in different regions. The second solution is a new mode of increasing credit and guarantees called credit guarantee [

45], which relies on a society of rural acquaintances and depends on the relationship of industry, consanguinity, and geography.

5.3. Government and Users

The key to reducing the cooperative resistance between the government and users is to tap the endogenous motivation of the users. Like the proverb, “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime”, the government’s support for inclusive finance in rural areas can only help in the short term, and the government subsidy is the “fish.” The practice of increasing users’ income, improving users’ financial literacy, and developing rural areas is the teaching how “to fish”, which is the long-term policy for the sustainable development of inclusive finance in rural areas.

5.3.1. Measures for Government to Motivate Users

The government can proceed considering three aspects: policy support, financial education of rural users, and consummation of a rural credit system. Firstly, the government should provide positive policy support; adhere to the rural revitalization strategy; support agriculture, rural areas, and farmers; improve the social security system; and objectively improve access to financial services for users. Secondly, the government should strengthen the financial education of rural users and increase their willingness to participate in inclusive financial construction. Financial education includes fundamental financial knowledge, financial culture, and financial philosophy, among which financial culture is one of the important soft strengths of inclusive finance construction in rural areas. Rural financial culture takes credit culture as the core; makes modern contract consciousness deeply popular; and gradually leads farmers and rural financial institutions to form correct codes of conduct, ways of thinking, and concepts of values. Thirdly, the government should improve the rural credit system. The first step is that the local government should actively carry out rural credit rating activities; comprehensively promote the construction of credit towns, credit villages, and credit users; and help farmers to cultivate sound credit awareness and achievement. The second step is to standardize the rural credit rating market and provide accurate and effective credit information services for relevant departments. At the same time, a disciplinary mechanism should be established for those organizations that intentionally deceive or issue false information to improve the market credibility and social influence of the rural credit rating industry. The third step is to establish a credit information collection and sharing mechanism for small- and medium-sized enterprises and consummate the evaluation system of their information collection, credit evaluation, results application, news releasing, and financing. Further, increase information exchange and sharing between relevant departments, improve the accuracy of information collection, and realize the standardized operation of a financial credit information database.

5.3.2. Measures for Users to Cultivate Endogenous Power

First of all, users should cooperate with the government’s work and actively improve their learning ability, cognitive ability regarding consumption, and their own financial literacy. In addition, learning to cultivate their own power is particularly crucial [

46], because “the ability of subjects will affect the power contrast among the subjects of financial markets as well as the interest game in financial activities, which is related to the financial market entry, financial transactions, and the fairness of financial welfare distribution”. Finally, users should keep up with the pace of the Internet era, master the basic skills of digital inclusive finance, use the Internet to understand the latest government policy, and be a new type of farmer in line with the trend of the times.

6. Research Limitations and Prospects

To sum up, based on the theory of synergy, this work analyzed the behavior motivation and cooperative resistance of the three subjects in the rural inclusive financial system—the government, financial institutions, and users—and put forward corresponding countermeasures for sustainability.

Figure 8 reflects the three subjects of China’s rural inclusive financial system and the cooperative resistance.

The limitations of this paper are as follows. One is that this paper draws conclusions using the kind of descriptive statistical analysis used in most studies. For the analysis of cooperative resistance, it is difficult to carry out an empirical test because the research is biased at the macro level. For example, the influence of the government on financial institutions or users was mainly determined through measures such as policy implementation and supervision, but such measures are not easy to quantify into intuitive data forms. Even if a comparative analysis had been carried out before and after the implementation of the policy, it would still have been difficult to design the model and select suitable control variables. In order to address the above limitations, a numerical simulation was used to enhance the reliability of the results. However, this is still not as rigorous and persuasive as empirical results. The other limitation is the lack of sufficient discussion of the potential endogeneity issue and its remedies. Some empirical articles consider endogeneity problems, which has an important impact on the authenticity of the results [

47]. Since this work did not conduct empirical research, endogenous problems were not considered.

Finally, the prospect of future research is as follows. After defining the subjects in the system, subsequent research can proceed from the perspective of the “lubricant” in the inclusive financial system, that is, the circulation and feedback mechanism of credit and capital flows. There have been many studies on capital flow in inclusive financial systems, but the related research on credit flow is scant. The study of credit flow can be carried out from the perspective of how to define, accumulate, and provide feedback for the credit of the served users in the financial system; how to interact with capital flow; how to form a dynamic cycle; and so on. Currently, the importance of credit is becoming increasingly obvious. The construction of a credit system in most developed countries has been thorough, but in most developing countries, the credit system is scarce, especially in rural areas of China. The root cause of the lack of motivation for financial institutions to provide services to rural users is the existence of bad debt risk caused by a breach of trust. Putting forward constructive suggestions in any step of credit flow will be a major breakthrough in research on inclusive finance in rural areas.