1. Introduction

In academia and the public debate, there is increasing attention being paid to the environmental and societal burdens related to an ever-expanding amount of solid marine litter—from glass bottles to aluminum cans to fishing nets. The dominant proportion of marine waste is plastic residues, and UNESCO estimates that plastics constitute 60% or even 80% of all waste deposited in seas and oceans [

1]. Approximately half of the waste found on beaches is the remains of all kinds of disposable plastic packaging or products [

2]. The need for innovative forms of regulation, mitigation, and behavioral adaptation are widely recognized [

3], but the necessary multi-layered actions seem to lag behind the seriousness of the challenge [

4]. Many dimensions of environmental challenges in marine and coastal zones and in the hydrosphere are drawing increased attention worldwide [

5]. In particular, there is strong public and academic emphasis on overtourism problems in connection with marine and coastal ecosystems [

6]. The tourism and leisure sectors are, on the one hand, contributing directly and indirectly to pollution [

7]. However, recreational activities are also negatively affected by unclean seas and beaches [

8]. In this respect, tourists and recreationists, as well as their service providers, are evidently in a sort of ‘double contract’ with the environment.

The article aims to examine the modern forms of the environmental actions that seek to prevent and mitigate pollution in recreational marine environments and beaches. Conceptually, the paper introduces a new term, that of “relational environmentalism”. The term expresses the idea that successful campaigning, communication and environmental patrolling is a matter of building alliances and exchange logics across a variety of boundaries, both institutional and personal [

9].

The study builds on evidence from the Danish environmental campaign “The Marine Environment Patrol” (in Danish Havmiljøvogter). The Marine Environment Patrol was established in 2006 and currently counts close to 25,000 members who voluntarily spend their leisure time and efforts reporting oil spills and cleaning marine litter along the 7314 km of the Danish coastline. The activity engages people who are active in marine sports, tourists and locals who enjoy visiting the beaches for outdoor activities and/or relaxation. From its start, the campaign has been innovative in its format and organization, and its persistence, as well as its gradual development over time, makes it particularly suitable for examining the forms of environmentalism and particularly the relational aspects of environmentalism, which are an issue of interest to this article.

Engaging the public in cleaning activities is not new. Back in the 1980s, the embryonic period of ecotourism and sustainable tourism, the world was shocked when the Annapurna Conservation Area in Nepal not only banned littering by trekkers but also started to require that tourists pick up trash left by themselves and others and dispose of it in the proper place and manner. The travel audience was even more astonished when it learned that local tour operators had introduced tours with the specific purpose of cleaning the area and that participants of such tours were supposed to perform this job voluntarily [

10]. Since then, the idea of responsible behavior in nature has become widespread, and litter collection events and campaigns have become commonplace [

11,

12]. The idea of participative action fits well with the general trend in leisure and tourism that calls for more pro-environmental actions and meaningful experiences [

13], not the least in marine environments [

14].

Although often questioned due to the embedded paradoxes, the demand for stronger environmental responsibility seems to have increased and the requests for lending a hand during holidays and leisure time for a ‘greater purpose’ are becoming more common [

15,

16]. As the public cost of cleaning up coastal areas is potentially disastrous for many governments worldwide, relying on volunteers has become the prevalent alternative [

17]. For example, a number of nonprofit organizations are working to bring visibility and change to the amount of plastic waste in the oceans. Founded in 1972, the Ocean Conservancy works to protect ocean species such as whales, seals and sea turtles as well as their natural habitats and the communities that surround them, and its International Coastal Cleanup mobilizes over 600,000 volunteers to clean up beaches and coastlines each year. In this sense, the cleanup is an expansive movement. Volunteering programs strive to combine attractive packages with purpose, entertainment and social benefits [

18].

Monitoring tasks are also handed over to volunteers, framed under citizen-science umbrellas [

19]. The shift of (sometimes statuary) obligations from the public institutions to volunteer organizations has received a response in the governance literature [

20], an issue that will be further addressed in this article with a reference to the Marine Environment Patrol.

The study proceeds as follows: The next section will expand the definition of the term relational environmentalism and frame it in the context of volunteering in coastal and marine cleaning and monitoring activities. Afterward, the history and operational background of the Marine Environment Patrol will be outlined. Then, the method of data acquisition and analysis will be explained. The results section will focus on outlining the development of the relational categories found in the material and on the analysis of the substance and development of the relations as well as on explaining what has exchanged in the relationships. Finally, in the discussion and conclusion, wider managerial and theoretical perspectives will be highlighted.

2. The Concept of Relational Environmentalism

Environmentalism can be defined as ‘the advocacy of the preservation, restoration, or improvement of the natural environment’ (Merriam-Webster). Following this definition, environmentalism is expressive but can also be multifaceted [

9]. Wolf-Watz, Sandell and Fredman [

21] distinguish between environmental attitude and environmental behavior in nature-based recreation. The former pertains to ‘an awareness of environmental problems and a dedication to protection’ [

21] (p. 194), whereas the latter means ‘the actions actually taken based upon particular attitudes’ [

22] (p 81). It seems justifiable to assume that a pro-environmental attitude positively affects environmental behavior and the choice of nature-based activities. For example, a study conducted by Kaiser, Wölfing and Fuhrer [

23] shows that one’s subjective norms and normative beliefs regarding the environment affect the intention to behave according to ecological norms. For example, based on primary data collected among Spanish respondents, Fraj-Andrés and Martínez-Salinas [

24] showed that environmental attitudes have a significant effect on ecological behavior and that the level of environmental knowledge moderates this relationship. Active contributions to the improvement depend on the environmental situation in the geographical space of the recreational activity and on numerous other personal characteristics, including relational characteristics.

Environmentalism is also regarded as a political manifestation and a kind of civil action. It can be seen as an ethical movement that seeks to improve and protect the natural environment through changes in the otherwise potentially environmentally damaging activities. Studies about tourism and practical environmentalism are embedded in eco-tourism concepts and take a consumer-oriented approach, where the availability and promotion of environmentally sensitive forms of accommodation and eco-certified experiences lead towards behaviors with less harmful effects [

25]. There is a solid research tradition in responsible tourism and eco-leisure that underlines the variety of forms of such actions [

26,

27,

28].

Environmentalism, however, may also imply the mobilization and expression of extended moral opinions or opposition [

29,

30,

31]. The anthropocentric approach enhances narratives about how environmental degradation affects human lives, including the quality of touristic and recreational experiences. There is a range of modes related to the manifestation of environmentalism, of which many have grassroots origins and scopes that go beyond the specific situation of consumption and enjoyment. Such interventions range from protests by use of media to massive objections in formal complaint systems to raising the roof with protest groups and through meetings and demonstrations, to lobbying, and perhaps further to occupations, barricading and other more radical attempts to hinder or counteract the observed negative effects on nature [

32].

The outline above suggests that there is a variety of forms of environmentalism and that it is relevant to address a continuum of human concerns and actions [

33,

34]. However, where do the ‘relational’ aspects fit in? As the term ‘relational environmentalism’ is not developed to any extent in the academic literature, there is a need to scrutinize and determine the approaches and dimensions that can be of explanatory value for understanding a campaign such as the Marine Environment Patrol and similar initiatives in the leisure and tourism context.

The notion of agency, as emphasized in the description of environmentalism above, necessarily involves actors whose positions are meaningful only in relation to other actors. Hence, the relational theory is an approach that offers a fertile agenda to develop our understanding of the patterned relations between actors and the development of such relations. In relationships, actors may seek to change the behaviors of others or seek to empower others to change their own behavior [

35,

36]. It is also assumed that the relations provide value to the particular actors and to the networks, for example, to the surrounding communities in which the implications of actions can be affected and progressed and from whom a response can be acquired. Dynamic interaction involves, among other things, knowledge sharing, problem-solving and relationship building. The existence and importance of such relations have been observed by Kwiatkowski, Hjalager, Liburd and Simonsen [

16] in a case of environmental volunteering and collaborative governance in Danish protected areas.

Relations link people, organizations, and institutions. Some strands of the academic literature also include nonhuman agents, such as the actor-network theory [

37]. There are examples in the outdoor recreation literature that seek to understand the relationships between people and the physical nature and the biological processes [

38,

39,

40], and as expressed by Knippenberg et.al. [

33], the deep ‘

partnerships’ with nature that can flourish in human life. The relations have reconceptualized the meaning of humanity and moral attitudes to the environment [

34,

41], and these strands of the literature address how values can be transformed into environmental management. These approaches will, however, not be pursued in the article, which focuses on relationships between humans and institutional bodies composed of humans. Hence, the relational dimensions involve the social and communicative aspects rather than the material aspects of relations.

For the definition of ‘

relational environmentalism’ and ‘

relational approach’, there are other sources of inspiration in the academic literature. For example, the term ‘

relational’ is found to be combined with ‘

geography’ [

42]. This combination specifies the humans’ relationship with a place and the reconception of space and spheres as an effect of numerous dynamics. In this context, the goal is to analyze how production systems are organized and why this organization varies in different locations. More specifically, relational geography is concerned with the social and spatial division and integration of labor (organization), the positive and negative impact of historical structures, processes and events on today’s decisions (evolution), processes of knowledge creation and dissemination and the effects of technological change (innovation), and, last but not least, the interactions between economic agents and the formal and informal institutions that stimulate and restrict them (interaction) [

43]. Another interesting contribution is the so-called ‘

relational aesthetics’ that describes the fostering of interaction and communication between the artist and viewer through participatory installations and events, when experimenting like this, the movement at times pushes the boundaries of art’s definition in controversial directions [

44]. This type of transformative impact is what this article wants to excavate with the term ‘

relational environmentalism’. Thus, the interest is not only in what relational environmentalism is but also in how it is assembled, reconnected, enacted, and ordered.

To conclude, there is no established definition of ‘relational environmentalism’. This study has thus developed the following definition:

“Relational environmentalism is a movement of humans who purposefully interact with each other as well as external organizations in a variety of dynamically developing ways in order to affect the perceptions, motivations and practical actions for the caretaking of endangered natural environments.”

3. The Marine Environment Patrol—Its Origin and Development

The Marine Environment Patrol was established in 2006 by the Danish Armed forces. The Danish Armed Forces are the organization that is, among others, responsible for the monitoring and handling of oil spills along the Danish coastal waters. As the coastline is fairly long and as oil spills have been quite common over the years, the monitoring was found to be a massive task for the naval and airborne departments of the Danish Armed Forces. The organization found it relevant to ask other frequent users of the marine environment, including recreational sailors, to report whenever they came across spills. The Danish Armed Forces organized a campaign called “Stop Oil Spill Now” and created an application for recreational sailors operating on the open sea to report their observations. The initiative was very well received in the sailing communities.

Over some years, the problem of oil spills became, if not solved, then significantly diminished as a consequence of stricter regulations as well as behavioral and technological changes, particularly in the shipping sector. The number of subscribers to the “Stop the Oil Spill” campaign declined. However, the environmental problems in marine environments had not diminished, and the marine litter issue had become more serious. The idea was born to address the campaign towards new target groups, namely, the recreationists who do not necessarily sail, but who enjoy time on the beaches, in the harbors, and in the natural areas along the coasts.

The Danish Armed Forces envisaged that there might be a problem with such an expansion, as the Royal Danish Navy can only legally patrol on the sea, while the municipalities and the Ministry of Environment are responsible for the beaches. With Solomonic wit, this was solved by referring to the naval nature of the tides, which deposit litter on the beaches. The Navy could then expand the campaign. The name was changed to “Havmiljøvogter” (The Marine Environmental Patrol) in order to widen the emphasis to more target groups and to include the marine litter more directly. In addition, the campaign was reconceptualized and took two approaches: One approach was to encourage the practical collection of marine waste and make the members contribute directly to the cleaning of the beaches. The other approach was directed to affect opinions and attitudes more generally and to mobilize attention in society towards environmental challenges. The Marine Environment Patrol has remained under the organization of the Danish Armed Forces, with one full-time employee and a number of freelancers who solve a variety of communication and campaigning tasks.

Twice a year the Marine Environment Patrol sends letters to members that contain a high-profile and informative magazine and rolls of red bags to collect trash in. There are other gadgets and gifts that help members advertise their environmental awareness. In addition to running an official webpage and magazine, the Marine Environment Patrol administrates a Facebook page that is the main instrument for continual communication with members and others who are interested in the marine environment. The campaign is also very visible at fairs, events, and festivals for boaters and people with sailing and marine interests, and this presence is used to recruit members and to spread information about marine waste.

In 2014, the Marine Environment Patrol started the Junior campaign. This move was aimed at affecting the attitudes of the younger generations and also the result of the observation that committed children are very efficient and convincing communicators to parents, grandparents, and friends.

The membership has grown gradually over the past years: in 2019, the Marine Environment Patrol had 25,000 members. Overall, the Marine Environment Patrol cannot, in terms of capacity, be characterized as a very significant player in the environmental scene, but it is the largest organization of this kind in Scandinavia.

4. Research Approach

4.1. Research Strategy

The main ambition of the article is to examine environmentalism with a special emphasis on relational aspects. Thus, the paper aims to develop an understanding of how people and organizations interact in a variety of dynamically developing ways for the caretaking of endangered natural environments. As social media are very important carriers of relations between people, it was decided to use the Marine Environment Patrol’s Facebook site as the source of evidence for content analysis [

45]. Social media content allows the study of human activity and outreach across time, and it permits the examination of large data sets of both quantitative and qualitative nature [

46,

47].

4.2. Sources

A full data set of Facebook content was established in collaboration with the Marine Environment Patrol, covering the years 2014–2019 (June). The dataset consists of 456 posts. Many of the posts and comments contain links to external resources, of which the most common are videos, newspaper articles, and TV reportages. As the site is openly accessible, these sources could be and have been consulted with normal Facebook access. Social media is of particular interest in assessing the development of a “movement”, and the content, communication formats, and relational direction rapidly change according to new needs and opportunities [

48]. In this sense, the source fits the purpose of the study well.

4.3. Protocol Development

‘Relational environmentalism’ is a term that has not yet been defined in the literature. Furthermore, there are no predefined categories of relational environmentalism to be used, and thus, a rationale for the study is, in fact, to establish the first conceptualization of the concept as well as its analytical categories. To establish relevant categories, the content of all posts was read several times, and notes were taken for indications of relational aspects. Several relational terms were considered, and many were discarded through this process. It is worth mentioning that this investigative process could not be undertaken by content analysis software, such as NVIVO, as the relational aspects are often more subtly expressed in posts and a matter for interpretation. Accordingly, categories in the protocol were only consolidated after several iterative rounds, which was an integral part of the research methodology. The main task was to construct relational expressions that could be clearly defined and mutually exclusive and that would reflect the issues as they appear in the research aim.

After this work process and consolidation had been completed, the protocol included the following eight categories, which will be explained in greater detail in the analysis section:

Inviting

Informing

Coaching

Norm enforcing

Politicizing

Mobilizing

Intergeneralizing

Bridging

4.4. Data Organizing and Coding

The protocol was constructed to catch data in a systematic way throughout the reading process. The posts were only consulted once in a systematic work process, which held the Facebook supplementary resources open on another computer. Each post was assigned to one or more of the categories mentioned above. For each post, additional data, including the number of likes, shares, and comments, were also collected. It was possible to code all posts, except for 55 posts, and the final data set contained 456 posts, a number large enough for a quantitative analysis. The posts that were not categorized mainly contained a repetition of already published posts or short information that could not be deciphered from the current analysis standpoint.

One of the authors undertook the total coding process to ensure consistency. The other author control checked all the posts, and in case of different opinions regarding a post’s categorization, an additional discussion was conducted to find a compromise. Consequently, the subjectivity of the categorization was limited.

4.5. Data Analysis

The database was transferred to SPSS. The number of posts and relations were sufficient to perform some further, albeit still statistically simple analysis, to establish evidence about connecting types of relations and their development over time. Texts from the Facebook posts were reintroduced to exemplify and provide substance to the relational categories and the nature of environmentalism. A versions of this article was discussed with staff members of the Marine Environment Patrol managerial team, who offered valuable additional information and explanatory evidence. The responsibility for this article’s final version rests, however, solely with the authors.

4.6. Methodological Limitations

The advantage of social media content analysis is that it covers a large pool of information and works well for analyzing relational issues. However, there are also limitations. The media may not grasp the full breadth of the litter collection activities, as the members may also communicate their involvement on platforms other than the Marine Environment Patrol’s. There may also be a bias towards the most communicative actors, which in this case is the Marine Environment Patrol organization. Accordingly, the study cannot claim to be all-comprising in its attempt to examine relational environmentalism forms, but it provides a quantitative insight that has not been previously available. A case-based follow-up could be a way to supplement the evidence given here. Here, the relational dimensions are mainly communication and social connecting. Relational aspects of, for example, materials and finances, could also be important for a full understanding of what relational environmentalism may entail, but this will be for further studies to address.

5. Qualifying the Relational Dimensions in the Marine Environment Patrol

This section frames the dimensions overall, and it explains the categories and provides examples of the relational environmentalism as it emerges in the content of the Marine Environment Patrol’s Facebook page. The analysis draws on the evidence about the practices of volunteer environmental activity and the nature of relationship building. The initial analysis of the full content of the 456 posts led to the identification of eight categories, and in the following section, they will be explicated, and relevant examples will be provided. This categorization, emerging from the analysis, is new to the literature on relationships in environmental action and represents a major contribution of the study.

5.1. Inviting

This category refers to relationship building and covers the campaign elements meant to expand the Marine Environment Patrol’s network. The aim is to raise interest in environmentally oriented actions and, consequently, to recruit new members. The posts from this category disseminate activities of the Marine Environment Patrol at events where many people are present. Campaigning takes place at sailing and yachting events, at the annual “Nature Meeting” and at other events of importance for marine recreation. Photos posted on Facebook show not only the booth of the Marine Environment Patrol but also the crowds and the reactions from the audience. The presence at events provides an opportunity to build individual relations through personal touch and to deliver gadgets to the people, for example, bags to take on the first trash collection trip. On occasion, the campaign alerts the TV media to report on the activities of the Marine Environment Patrol. Exposure to national or regional TV substantially raises attention to the campaigns.

The relationship-building of the Marine Environment Patrol took place and still takes place first and foremost in environments and communities that are connected to the marine environment and to the Danish Armed Forces. Therefore, the Danish Naval Home Guard offers comradeship to the volunteers and is a way of not only ensuring an active membership but also maintaining social relationships once the active service of the Danish Armed Forces personnel comes to a stop and as new life purposes and interests have to be found. Environmentalism is perceptively brought into the potential social and relational vacuum.

5.2. Informing

The posts in this category of relational environmentalism disseminate knowledge among users related to the environment and sustainable development, and they are mainly, but not exclusively, launched by the Marine Environment Patrol secretariat, who employ, for example, marine biologists. The knowledge dissemination aims at creating more awareness and education, thus providing members with a knowledge foundation for their joint activities. Potentially, members are better able to understand what they observe on trash collection missions. Knowledge feeds are by far the longest texts, supplemented by photos and (links to) videos. One example is a concise and detailed feature about the ingredients in chewing gum and cigarette stubs, such as lead, cadmium, tars, synthetic gum, etc. Many reports are about marine wildlife and how oil spills and plastic affect habitats. It is important for the organization to emphasize facts-based and exciting information in its own communication rather than to create propaganda.

The Marine Environment Patrol relies heavily on the close connection with the Danish Armed Forces. There are numerous on-site videos and photo reports from the environmental monitoring undertaken by the Royal Danish Navy and the Royal Danish Airforce. The communication is, however, not only strictly fact-based but also often to some degree thrilling, with an appeal to the “boyish” purpose of being important for the broader persistence of the Marine Environment Patrol case.

5.3. Coaching

This category embraces the Marine Environment Patrol work with the members to adjust their behaviors and advise them about how to act in nature. On an ongoing basis, the Facebook content posted by the Marine Environment Patrol and its members interprets, finetunes and celebrates how to be a “really good” marine patroller. The posts exhibit and assess how people do the litter collection in practice.

A friendly competitive environment is created. The Marine Environment Patrol provides the members with bags with the large caption “Havfald”. Havfald is a combination of two Danish words: “hav” (sea) and “affald” (trash). Numerous posts provide pictures of large heaps of filled bags with the Marine Environment Patrol’s logo. The encouragement is also needed. Many posts refer to the fact that the beach can be cleaned effectively one day, but depressingly, the next day the tide and wind bring in stacks of new trash. The effort is never-ending, and the posts tell stories about how people have organized their daily outdoor life so that they will be able contribute and at the same time enjoy nature and the social relations of outdoor activities. When in use, the bags are recruitment measures.

As a supplement, the Marine Environment Patrol provides gadgets, hats, car streamers, etc. To judge from the comments, these symbolic objects mean much to the members. The objects help them communicate their actions and, for some, they arouse interest among strangers.

Peter from Fanø is a person featured a number of times by the Marine Environment Patrol and the people from the local community, who unified in a local “Clean Fanø” action. Originally, Peter was somewhat opposed to this kind of environmentalism but changed his mind after observing the trash and admiring the energy of the members. He now patrols extra intensively, and he uses his car and trailer to collect filled bags from the beach area. He is also active in approaching curious interested tourists, and he finds it easy to convince them not only to be aware of their own littering but also to do rounds with the bags. Peter has become a role model for the Marine Environment Patrol behavior.

Working with celebrities is not as widespread, as may be seen in some international campaigns [

38]. This is a deliberate strategy.

A number of posts are kind reminders by the Marine Environment Patrol to be aware of the dangers, for example, of handling types of litter that should be handled by professionals.

5.4. Norm Enforcing

This category of posts includes more rigid elements of moral communication. Such communication is concerned with the perceptions people have about the environment and how these perceptions shape their behaviors and attitudes towards the environment [

49]. Posts are strong in advocating consistent environmental behavior by blaming those who fail to align with the norms. Theory and practice in communication emphasize that this may be an efficient way of creating a group feeling and responsibility [

50].

An example is a video that exposes the content of the stomach of a dead whale with an amount of plastic. Animals such as seagulls smeared in oil or trapped in pieces of fishing nets are also often shown on the Marine Environment Patrol, and the comments are harsh. There is a strong relationship with the animals but also with the humans who save the animals and who occupy a special position in terms of legitimate agitation.

Alarming pictures and videos raise interest and action, and the Marine Environment Patrol community frequently shares photos and videos documenting their achievements.

5.5. Politicizing

Relationship building in this category concerns the links, oppositions or alliances with the political levels at the regional, national and even international levels. While the Marine Environment Patrol is indeed a grassroots way of conducting opposition, there is an awareness that the fundamental problems will not be solved without a more comprehensive governmental action and regulation. The relations should also, therefore, be developed in a multilevel way.

There are examples of how the Marine Environment Patrol uses the power of membership to appeal to governmental bodies and marine corporations. For example, such actors were strongly urged to do something about the waste spills from the approximately 100,000 annual marine transfers in the Danish waters. Another appeal was directed to the actors in fisheries because the fishing fleet frequently dumps or loses its materials, arguing that more could be done to avoid ghost fishing gear. Such appeals can be efficiently communicated with the amount and categories of trash that the Marine Environment Patrol members find on the beaches.

In 2017, The Marine Environment Patrol was featured as an example in the EU plastic strategy. The campaign was portrayed as a good example of how to engage the public. Furthermore, the Patrol was described as a contributor to tackling the challenge of marine litter by raising awareness, increasing surveillance, and preventing and removing marine litter.

5.6. Mobilizing

This category embraces posts that aim to promote specific collaborative actions among the Marine Environment Patrol’s members, who aim to team up in locally arranged cleaning actions. This category of relational environmentalism mobilizes people in groups, raising resources in specific communities and keeping up the momentum. There is an appeal to participate jointly and mutually in cleaning activities. Therefore, the relationship-building mechanisms in joint action initiatives are about stewardship, with a clear attachment to the local area, and they are situated where the members in the neighborhood might feel morally obliged or emotionally motivated to be a part of waste collection missions [

18,

51]. Such endeavors typically have a short duration and can easily be celebrated together afterward.

Examples show that calls for action are opportunities not only to contribute to the campaign but also to meet with friends in the community. Thus, one event was about establishing and filling bag dispensers in a beach area, a task that demanded tools and physical strength, but with an achievable success and a clear symbolic value. Another example consisted of just a time and a meeting place, and a ‘come and join’. The social element was particularly essential in this case, as discussing the trash that is found is more entertaining than picking it up alone.

5.7. Undergeneralizing

As mentioned earlier, campaigning for an environmental purpose has a very long-time perspective, and the Marine Environment Patrol has envisaged relationship-building across generations: in particular, starting with the children and proceeding to the parents and grandparents is of significant value in this the case. Relational environmentalism is supported by family trust and the fact that most parents want to see their children involved in outdoor activities. There are many very personalized and deepfelt narratives of what can be obtained in terms of relational enhancement. Family groups join in targeted missions after trash-collecting, they spend time “analyzing” the findings and theorizing about the origins of the waste and the means of disposal. The children are often much keener than the parents and grandparents on the continued collection trips. They talk about the trips to their friends and teachers in schools, and as a result of this and the Junior campaign, the Marine Environment Patrol has built stronger relations with the youngest generation.

Children’s actions, reflections, and responses form very powerful content on Facebook. For example, the juniors’ relationship building is connected not only to the environmental values and prospects of the trash collection but also to the entertainment element. Laura, an 8-year-old junior member, exhibits her collection of “fun dolls” built from the trash that she found on the beach. Another interesting example is that of the 12-year-old Adelina, who found a small bag that contained goods from a German sailing ship that sank a year before. Based on the information from a wallet, Adelina’s parents contacted the German owner of the bag and contacted him to send back his belongings. This kind of story creates an additional interest among young members, as it adds an element of unpredictability, adventure and curiosity.

5.8. Bridging

This category of posts comprises evidence of how the Marine Environment Patrol aligns and cooperates with other types of volunteer organizations to enhance their effect and awareness. Referring to Granovetter [

52], bridging is about enhancing the purpose and activities into types of organizations and frameworks that are different in purpose and scope. Such alliances are important for supplying knowledge but in this context also for reaching further audiences and gaining commitment.

Regarding the bridging format, there are many environmental organizations and a great number of volunteering bodies that may already have or could have overlapping purposes with the Marine Environment Patrol. The Scouts movement is one organization mentioned but also the Norwegian KIMO (Kommunenes Internasjonale Miljøorganisasjon), which was founded by local municipalities with a shared concern for the state of the environment. KIMO is an international environmental organization designed to give municipalities a political voice at the regional, national and international levels. Collaboration can enhance the communication and the relationship-building capacity of the Marine Environment Patrol, and there are a number of examples of how this works.

Tourism organizations in the coastal areas increasingly perceive the Marine Environment Patrol as a partner in the expression of “local-hood” and the joint concern of tourists and citizens about the quality of the tourist environment. An example is Frederikshavn Tourism DMO, which actively supports the Marine Environment Patrol’s activities.

However, in the case of the Marine Environment Patrol, there is a certain priority to link up with the immediate environment. Thus, the Danish Armed Forces with all its different entities is clearly a major resource for the Marine Environment Patrol in terms of its possession of material and knowledge for the campaign and its implementation. However, the civil society often considers the Danish Armed Forces a conservative and closed organization, and in this respect, the alliance with the Marine Environment Patrol may improve the image of the Danish Armed Forces as an organization that is also deeply engaged in civil tasks. The alliances made with the resources of the Danish Armed Forces emerge on Facebook with, for example, local municipalities and other nonprofit organizations, such as Worldperfect.

6. Quantifying Relational Environmentalism

The Facebook posts were carefully reviewed and coded, and the current section provides an overview of the different categories of relational environmentalism and the correlations with the Facebookers’ reaction to the posts’ content, namely, ‘likes’, ‘shares’, and ‘comments’. The purpose is to enhance an understanding of what kind of relational environmentalism is built and how, as well as what categories of posts appear to be the soundest (cf.

Table 1).

During the period 2014–2019, inviting, informing and coaching were by far the most frequent types of relational activities. This might not be surprising, as the goal of the Marine Environment Patrol is to increase membership and work with the members as to how they perform their patrolling role. While the organization is keen on inviting content from the members, there is also a need to inform about small as well as large matters. All other types of posts are less frequent, and politicizing types are the lowest. Until now, the Marine Environment Patrol has not been used much as a lever for political influence on environmental matters. Bridging is not frequently observed. After the junior initiative, however, the Marine Environment Patrol began to look for alliance partners beyond the Danish Armed Forces in the sailing and yachting communities.

The average number of likes is generally low, particularly when taking into consideration that there are 25,000 members and 8,300 Facebookers that follow and like the Marine Environment Patrol fan page. The figures seem to be even smaller when compared with global organizations of similar scope (e.g., The Surfrider Foundation, The Oceana) with approximately 300,000 and 60,000 followers, respectively. Norm enforcing posts receive a higher number of likes than the other seven categories, possibly because they appeal to people to demonstrate that they are opposed towards particularly environmentally controversial behaviors. The same category of posts is also more frequently commented on than the remaining seven categories. Sharing is highest when the posts are in the category of bridging. This suggests that the Marine Environment Patrol can achieve some additional attention by linking to organizations and networks beyond the immediate boundaries. The differences in shares, likes, and comments are, apart from the above findings, relatively meager.

It is worth mentioning that due to the abovementioned multidimensionality of relational aspects, the coding procedure allowed each post to be assigned to more than one category. Nevertheless, the great majority of posts (345) were assigned to one category, whereas another 111 posts were assigned to two categories. Only a marginal number of posts (20) were assigned to three and more categories. The correlations between the categories were examined to increase the understanding of how relational approaches are mutually supporting (cf.

Table 2.).

Table 2 shows that there are not many positive and highly positive associations between the analyzed categories of posts, indicating that the forms of relational environmentalism are not easily combined or that the Marine Environment Patrol actors have not yet explored such opportunities. There are also some significant and yet negative associations, which may, in turn, suggest that certain modes of communication and relationship building do not work well together. The negative correlations (not significant) tend to be connected to the inviting actions. This does suggest that when attempting to recruit new members and motivating them to join, there should be neither an overload of factual information nor too much of a plea for behavioral adaption. The significant positive correlation (in bold) with the intergenerational category and the invitation category suggests that emotional and social aspects of relational environmentalism tend to be an advantage in terms of enhancing the purpose and activities of the Marine Environment Patrol. Generally, the intergenerational approach seems to be a good lever for the activities of The Marine Environment Patrol and for the concept of relational environmentalism.

There is an interesting positive association between the norm enforcement and politicizing categories. This may suggest that while the members of the Marine Environment Patrol are indeed active themselves, they still clearly recognize their own small contributions to the broader changes that will only be possible and of significant value if followed up by international political action.

7. The Dynamics of Relational Environmentalism

The Marine Environment Patrol has existed since 2006, but prior to 2014, it conducted social media activity with a more niche and narrow scope than currently. Developing the (social) media presence has increased membership. The use of Facebook as a means of environmental relationship building has also increased, particularly in the later years, as shown in

Table 3.

There is a growing tendency in all the analyzed categories, although it should be taken into consideration that in some categories, the overall numbers are small. Not surprisingly, the lately introduced intergenerational activities have come up recently. Apart from that, the tendency is the most evident in the development of the mobilizing initiatives category. This may be interpreted as a shift in the relationship enhancement activities from the Marine Environment Patrol organization to the members, who have gradually used the platform more independently to find allies in specific activities.

The attempts to increase membership are still important ingredients of the Facebook content, and in this sense, campaigning is not at all rendered obsolete. However, other organizational bodies and groupings are moving in as partners, as suggested by the increase in posts that are categorized as “bridging” in this analysis.

8. Discussion

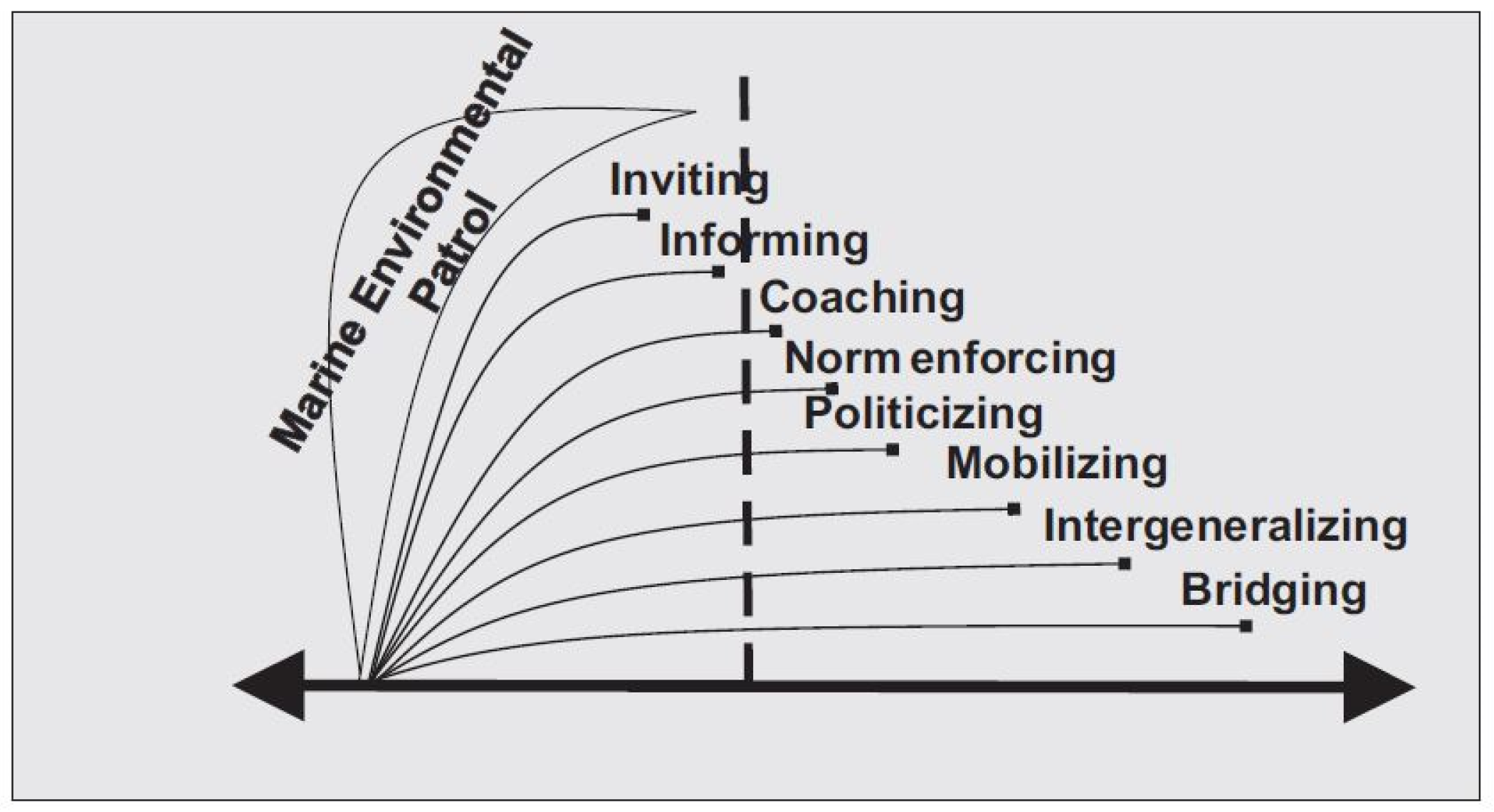

The study aims to investigate the forms of relational environmentalism, with the Marine Environment Patrol taken as a specific example. The initiative mobilizes local recreationists and tourists, individually and in groups, for cleaning actions in coastal areas. The membership is still modest but has grown over time, and the organization generally receives both funding and widespread sympathetic support, with the campaigning being a factor, among quite a few other factors, in the field of combating litter pollution in marine environments. The findings can be summed as “reach” in relational environmentalism. The Marine Environment Patrol works along the control-autonomy axis, gradually moving towards the right side of the figure, as the Marine Environment Patrol matures and acquires more members.

To support the theoretical development of the forms of relational environmentalism, the content analysis of the Marine Environment Patrol’s Facebook site led to the identification of eight different categories.

The robustness of the dimensions and their explanatory value is emphasized when the analysis suggests a development that gradually gives more time to relationship-building activities that are initiated by the members themselves and that produce likes, shares, and comments. Gradually, the Marine Environment Patrol is becoming an organization that is letting go of some of its hands-on control. The general social media trends invite such more or less unpredictable contributions, and as seen here, from the campaigning point of view, these can be considered productive expansions [

46]. More generally, this is concurrent with studies in the field of environmentalism, which also emphasize a trend towards increasing autonomy and subdivisions into subgroups and fragments [

50]. In this sense, the Marine Environment Patrol is moving from being a mainly top-down governance type of an environmental movement to becoming a much more bottom-up type of campaigning that allows users and followers to contribute to and interact with the content. Overall, this seems to benefit and enhance the recognition of the Marine Environment Patrol.

The Marine Environment Patrol is keen on providing the members with accurate, updated and consolidated information and behavioral advice. The response on Facebook leaves no doubt that the members appreciate this. However, an interesting finding is that practical environmentalism and enhanced relationship building alert members about the more outrageous types of marine pollution exposed by the Marine Environment Patrol or its members. This illustrates the importance of the emotional element in relational environmentalism, whereby a distinct and non-anonymous scapegoat can mobilize both the network expansion and specific actions.

The Marine Environment Patrol was established by the Royal Danish Armed Forces, and contrary to many environmental movements, it was (and still is to some extent) more governed from the top-down rather than from bottom-up. This paradigm has slightly changed, and the Facebook profile contributes to the more autonomous developments: the content exposed under the bridging headline supports this conclusion. Aligning with the Danish Armed Forces is, however, surprisingly beneficial, not only because it is in the possession of useful staff, material and knowledge resources, but also because it mobilizes categories of members who might not be accessible through other channels. The Danish Armed Forces, which is perceived in some circles as being closed, conservative and constrained, has gained access to relationship building with the population through the Marine Environment Patrol by exposing its civil environmental responsibilities and operations.

9. Conclusions

This article focuses on relational issues of environmentalism. Does the Marine Environment Patrol case and the observations made here have general importance? The Marine Environment Patrol is relatively small, and it also operates in the Danish context, but there are findings of considerable interest in the development of the concept of “relational environmentalism”. As stated in the introduction, there is no well-established understanding of the concept, and this is where this study makes a wider contribution.

Eight relational formats were identified, which are distinctly different ways specify the relations of importance for the progression of the environmental agenda. As stated in the definition, “relational environmentalism is a movement of humans who purposefully interact in a variety of dynamically developing ways to affect the perceptions, motivations and practical actions for the caretaking of endangered natural environments.” Relational aspects are, if not determining, then of critical importance for the perception and possibly also for the impacts of the Marine Environment Patrol. As such, knowledge offered by this article can be of key importance for future existence and development of the Marine Environment Patrol and similar initiatives.

Environmentalism develops dynamically over time [

9]. The lesson from the Marine Environment Patrol is that there is a period of time when one-way communication dominates, in this case, the inviting motivational relationship building and the dissemination of fact-based knowledge. However, relational environmentalism evolves into a phase in which the initiator takes on a more modifying role where the behaviors and actions are matters of negotiation and where the higher degree of autonomy of local groups and individuals gradually surfaces. At this stage, the particularly active members will be known to the organization and to other members, and anonymity is replaced by more reciprocity, independence, and involvement. Modifying this can be a challenge for an organization that started with a mainly one-way communication strategy, but in this case, the intergenerational approach was a highly efficient lever and illustrative support for this conclusion.

Environmentalism involves changing attitudes and practice, and this aspect may develop further than the mainly communication-based forms that are analyzed in this article. It is difficult to be very specific about this in the case of the Marine Environment Patrol, although annually, tons of waste is collected and disposed of as a result of the members’ efforts. The strategy of the campaign is fairly low key, and little is done to make the Facebook posts go viral in an attempt to agitate to wider audience groups. The use of “superficial” types of relationship building, such as through celebrities, is very sporadic, and the creation of bridging alliances with complementary types of movements and the environmental movement is in an embryonic phase. This suggests a “managed” spontaneity.

As shown by Wolf-Watz et.al. [

21], environmentalism emerges in many shapes, none of them more “correct” than others. There are some dichotomies between the unobtrusive and simple style of the Marine Environment Patrol on the one hand and, for example, the rebellious protest movements seen in most recent years that resist “overtourism” and the related environmental damages on the other hand [

53]. Common for contemporary forms of environmentalism is the focus on relationship building and the use of social media for this purpose. Relational environmentalism is likely to become more connected internationally in the future to gain power and influence, and social media can still be a remedy for relationship building [

9]. It is of critical importance to follow the intrinsic dynamics of relational environmentalism. In science and politics, the importance of recreation and tourism tends to be ignored as part of the solution to environmental problems. This study demonstrates that serious environmental matters and satisfying recreational endeavors are not at all incompatible. The dynamic, as illustrated in

Figure 1, suggests that further studies should focus more on the emergence and impact of bridging.

The main question for further inquiries in this particular case is whether the Marine Environment Patrol and other environmental movements can sustain and expand the commitment of the members over time or whether their activities are more just another “flash in the pan”. In terms of sustainability, citizen science pacts might be elements that convince others and achieve success in time and space [

54]. We still do not see the Marine Environment Patrol members creating systematic data for the analysis of the sources of marine waste, but many curious comments and questions on the Facebook site suggest that relational expansion might go in this direction.

The coastal zone is an important space for environmental action and relationship building, as shown in the evidence in this article and as demonstrated by other approaches [

55]. Leisure and tourism are paradoxical ingredients, but they are also part of the solution.